Abstract

Background

Physician burnout and emotional distress are associated with work dissatisfaction and provision of suboptimal patient care. Little is known about burnout among nephrology fellows.

Methods

Validated items on burnout, depressive symptoms, and well being were included in the American Society of Nephrology annual survey emailed to US nephrology fellows in May to June 2018. Burnout was defined as an affirmative response to two single-item questions of experiencing emotional exhaustion or depersonalization.

Results

Responses from 347 of 808 eligible first- and second-year adult nephrology fellows were examined (response rate=42.9%). Most fellows were aged 30–34 years (56.8%), male (62.0%), married or partnered (72.6%), international medical graduates (62.5%), and pursuing a clinical nephrology fellowship (87.0%). Emotional exhaustion and depersonalization were reported by 28.0% and 14.4% of the fellows, respectively, with an overall burnout prevalence of 30.0%. Most fellows indicated having strong program leadership (75.2%), positive work-life balance (69.2%), presence of social support (89.3%), and career satisfaction (73.2%); 44.7% reported a disruptive work environment and 35.4% reported depressive symptoms. Multivariable logistic regression revealed a statistically significant association between female gender (odds ratio [OR], 1.90; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.09 to 3.32), poor work-life balance (OR, 3.97; 95% CI, 2.22 to 7.07), or a disruptive work environment (OR, 2.63; 95% CI, 1.48 to 4.66) and burnout.

Conclusions

About one third of US nephrology fellows surveyed reported experiencing burnout and depressive symptoms. Further exploration of burnout—especially that reported by female physicians, as well as burnout associated with poor work-life balance or a disruptive work environment—is warranted to develop targeted efforts that may enhance the educational experience and emotional well being of nephrology fellows.

Keywords: burnout, graduate medical education, well-being, depression, fellowship, survey

Burnout is a state of mental distress characterized by the presence of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and sense of low accomplishment at work.1 Burnout among physicians is associated with adverse effects at both personal (relationship difficulties, substance abuse, depression) and professional (decreased productivity, work dissatisfaction, suboptimal patient care) levels.2 Physician burnout is considered a public health crisis and a threat to future medical practice.3 Causes of burnout include a host of factors at work (workload, regulatory pressures, poor work-life balance, lack of social support, loss of control) and at the individual level (compulsivity, poor personal coping mechanisms) that may exacerbate the response to stressors at work.2 Burnout among attending physicians in all specialties combined is estimated at 44%.1 Burnout is also common among medical trainees (medical students, residents, and fellows) and is concerning because of its association with self-reported medical errors, suboptimal patient care, and suicidal ideation.4

A 2017 survey of 15,543 United States physicians reported a burnout prevalence of 40% among nephrologists (range 23% [plastic surgeons] to 48% [intensivists]).5 However, information about burnout in nephrology fellows remains a critical knowledge gap. This is especially relevant because the high proportion of unfilled positions in nephrology fellowship programs is likely to compromise the future workforce.6 Medical students, residents, and non-nephrology fellows perceive nephrology practice to be based on complex pathophysiology concepts, comprising management of medically complex patients with chronic illnesses and a heavy workload that may cause distress at work.7 Nephrology fellows constituted the greatest proportion (22.3%) of the 121 fellows in 20 internal medicine subspecialties who left before completing their fellowship training in 2016–2017.8 Hence, we performed this exploratory study to investigate the prevalence of burnout and other emotional-distress measures using standardized, validated questions in a cross-sectional survey. We sought to identify personal and work-related risk factors associated with burnout in nephrology fellows, a high-risk group.

Methods

Study Design and Population

The target population in this cross-sectional study was all first- and second-year fellows in adult nephrology training programs in the United States. Our 11-item study questionnaire on burnout and well being was approved by the American Society of Nephrology (ASN) Workforce and Training Committee for inclusion in the annual ASN fellow survey that sought to capture information on demographics, educational perceptions, job market experiences, and future employment characteristics for all trainees.9 The survey had a total of 83 questions (inclusive of our questions) and was distributed electronically to all nephrology fellows in training who received complimentary ASN membership (n=1329). Because ASN extends fellow membership to all current trainees, the survey audience comprised all or nearly all adult nephrology, pediatric nephrology, research, transplant, nephrology critical care, interventional nephrology, and postdoctoral fellows. All respondents outside the target population were excluded as follows. Responses from third-year fellows (whose third year of fellowship is almost always dedicated to research) were censored because their clinical load is minimal (comprising coverage for other fellows or a few night or weekend calls) and not representative of service demands experienced during the 2 years of accredited nephrology fellowship training.10 Furthermore, there are sparse data on fellows pursuing additional training beyond the 2 years accredited by Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) due to a lack of a centralized accreditation organization.8 Pediatric nephrology fellows were excluded because their practice (although renal specific) is not a direct analogue of adult nephrology, with a smaller fellow pool (101 pediatric versus 808 adult nephrology fellows), different training protocols (three accredited years of training with a dedicated research year), differing etiologies and complexity of renal disorders, and higher attrition in pediatric nephrology fellows.8,11 Emails with a unique link to the online survey were sent to each potential respondent by ASN in collaboration with the George Washington Health Workforce Institute (George Washington University Institutional Review Board #051430; principal investigator Edward Salsberg). The consent page made no mention of “burnout” or “distress.” Participation was voluntary, responses were anonymous, and participants were eligible for incentives (ASN educational programs), with winners chosen randomly from participants at the survey’s conclusion.

After informed consent was provided, the respondent could start answering the questions, and responses were collected by Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap).12 Confidentiality was ensured by separating identifying information (emails, internet protocol addresses) from the rest of the data in a secure server at the completion of each survey. Frequent email reminders (approximately weekly) to the respondents and two reminders to the fellowship program directors were sent. Fellows could complete the survey over multiple sessions but once it was finalized and submitted they could not make further changes. The survey opened on May 1, 2018 and closed on June 11, 2018. In addition to third-year adult and pediatric nephrology fellows, participants who did not respond to any question on the survey and whose burnout status (primary outcome of interest) could not be clearly determined were excluded. A pilot study for system validation was performed on two nephrology fellows in May 2017 at the University of Vermont and these data were excluded from subsequent analysis. The questionnaire was reviewed both internally and externally and we edited the survey to enhance readability and ensure capture of key variables of interest. Content validity was established by seven nephrologists in the National Kidney Foundation (NKF) Education Committee. Approval for the study was obtained from the Committee on Human Research in the Medical Sciences, Institutional Review Board, University of Vermont, Burlington, Vermont (CHRMS 17-0516) under the exempt category.

Study Variables

Burnout

Questions from previously validated survey instruments were selected to measure different aspects of emotional health. Two single-item measures of burnout adapted from the 22-item Maslach burnout inventory (MBI), the reference standard for measuring burnout, were used.13 The two-item burnout questions have similar efficacy as the full-length MBI and have been effectively used in physician surveys due to its brevity.4,14 These items test how frequently the respondent perceived emotional exhaustion (“I feel burned out from my work”) and depersonalization (“I’ve become more callous toward people since I started this job”) on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from “never” to “every day.” Choosing “once a week” or more frequently to either item was considered a positive response and indicated burnout.14 A total of 650 online licenses for use of these proprietary questions were purchased from Mindgarden.com with research funds provided by the Division of Nephrology and Hypertension, University of Vermont.

Depressive Symptoms and Other Well Being Measures

Questions on depressive symptoms, positive influence at work, quality of program leadership, work-life balance, quality of life, and career satisfaction were included in the survey (Supplemental Table 1).4,15–18 All the questions were multiple-choice questions and one best response had to be chosen. Responses were on a Likert scale and addressed level of agreement (“definitely yes” to “definitely no,” or “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”) or frequency (every day to never). Permissions were obtained from the authors of the original questions for adoption in this study. Questions on demographics and information on the respondent’s fellowship program were also included in the analysis. After an iterative process of internal review, one question each on disruptive behavior and social support were considered pertinent to the survey and included in the final draft before survey dissemination (Supplemental Table 1).19,20

Statistical Analyses

Data are presented as descriptive statistics. Proportions were calculated with the denominator being the total number of respondents included in the analysis. Response rate was calculated as the proportion of eligible adult nephrology first- and second-year fellows in the United States who provided responses in this survey to conclusively determine burnout status. ASN’s membership database does not capture fellowship year, and the number of eligible United States adult first- and second-year nephrology fellows were obtained from the ACGME Data Resource Book for the academic year 2017–2018 (n=808).8 Because ASN membership is required to register for the In-Training Exam—taken by all adult nephrology fellows (>98% of fellows in 2014) and administered by ASN—we believe ASN’s 2018 fellow survey was directed to almost every first- and second-year adult nephrology fellow.21 Demographic data for the nonresponders were derived by subtracting the categorical data of the study sample from the ACGME data set and compared with the responders by chi-squared test of independence (ethnicity was not compared due to numerous missing responses in the ACGME Data Resource Book). The mean age of first-year fellows who did not respond to the survey was imputed from similar available data from the ACGME data set and study sample and then compared with the responding fellows by one-sample t test. Chi-squared and unpaired t tests were used to compare categorical data and continuous variables, respectively. Missing responses were reported as such. Logistic regression analysis with adjustment for all available covariates (mutually adjusted multivariable model) was performed to determine demographic and emotional health factors associated with burnout. Cases that had missing variables in the model were dropped by the statistical program when performing the analysis, leaving only complete cases and no imputation was performed. A priori, the following 10 variables were chosen for inclusion in the multivariable model: age, gender, fellowship year, international medical graduate (IMG) versus United States medical graduate (USMG), workload, relationship status, strong program leadership, social support, disruptive environment, and work-life balance, because we predicted 100 burnout events (based on 25% response rate and 50% burnout prevalence).22,23 Due to notable findings on depressive symptoms, additional regression analysis using the same 10 variables was performed to identify predictors of depressive symptoms. We did not include depressive symptoms in the regression model for burnout (and vice versa) because a strong correlation between these two constructs is known and overlapping features (such as exhaustion and feeling down) make it very difficult to differentiate between cause and effect.24,25 A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS, Inc., version 25.0 (Chicago, IL).

Results

The survey was distributed to 1329 nephrology fellows in the United States with ASN fellow membership, with 494 fellows consenting to participate. Participants with no responses (n=12), pediatric nephrology fellows (n=41), and those who identified themselves in their third year of fellowship (n=51) were excluded. Among the remaining fellows, burnout could not be determined in 54, who were censored. The final study sample comprised 347 of the 808 eligible adult nephrology first- and second-year fellows in the United States, yielding a response rate of 42.9%.

More than half of the fellows were 30–34 years old (56.8%) and male (62.0%) (Table 1). Most of the fellows were in clinical nephrology fellowship (87.0%) and the postgraduate years were about equally distributed (45.5% first-year and 50.1% second-year fellows). More than half of the respondents identified themselves as IMGs (62.5%). Respondents were commonly training in the southern (30.8%) and northeastern (27.1%) United States. Two thirds of the fellows were in a relationship (married or partnered, 72.6%), and nearly half of the respondents had no educational debt (50.7%). Two thirds of the fellows had applied to other specialties or general practice before choosing to pursue nephrology (63.1%) and three quarters of the fellows saw >15 patients on average in a weekday (75.8%). No statistically significant difference was noted between our study sample and the nonresponders in distribution of fellowship year or gender, although the proportion of IMGs versus USMGs and age of first-year fellows was higher in the nonresponders when compared with the responding fellows (Supplemental Table 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of responding first- and second-year nephrology fellows in the United States (n=347)

| Study Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| ≤29 yr | 23 (6.6) |

| 30–34 yr | 197 (56.8) |

| 35–39 yr | 78 (22.5) |

| ≥40 yr | 45 (13.0) |

| Missing | 4 (1.2) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 215 (62.0) |

| Female | 131 (37.8) |

| Missing | 1 (0.3) |

| Current fellowship type | |

| Clinical nephrology | 302 (87.0) |

| Research nephrology | 38 (11.0) |

| Transplant nephrology | 1 (0.3) |

| Interventional nephrology | 1 (0.3) |

| Other | 3 (0.9) |

| Missing | 2 (0.6) |

| Fellowship year | |

| First-year fellow | 158 (45.5) |

| Second-year fellow | 174 (50.1) |

| Missing | 15 (4.3) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 232 (66.9) |

| Partnered | 20 (5.8) |

| Single | 90 (25.9) |

| Divorced | 4 (1.2) |

| Other | 1 (0.3) |

| Missing | 0 |

| Racea | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 3 |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 142 |

| Black | 24 |

| White | 125 |

| Other | 55 |

| Missing | 0 |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 34 (9.8) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 313 (90.2) |

| Missing | 0 |

| Location of medical school | |

| United States | 126 (36.3) |

| Other countries and Canadab | 217 (62.5) |

| Missing | 4 (1.2) |

| Educational debt | |

| None | 176 (50.7) |

| $1–$200,000 | 100 (28.8) |

| >$200,000 | 67 (19.3) |

| Missing | 4 (1.2) |

| Nephrology as first choice | |

| Yes | 126 (36.3) |

| No (other specialties or general practice) | 219 (63.1) |

| Missing | 2 (0.6) |

| Number of patients seen in a weekday | |

| <10 | 17 (4.9) |

| 11–15 | 65 (18.7) |

| 16–20 | 110 (31.7) |

| 21–25 | 83 (23.9) |

| 26–30 | 35 (10.1) |

| >30 | 35 (10.1) |

| Missing | 2 (0.6) |

| Census region | |

| Midwest | 68 (19.6) |

| Northeast | 94 (27.1) |

| South | 107 (30.8) |

| West | 44 (12.7) |

| Missing | 34 (9.8) |

Number of responses for race does not add to 347 because multiple options could be chosen.

Five fellows attended medical school in Canada.

Burnout and Emotional Well Being

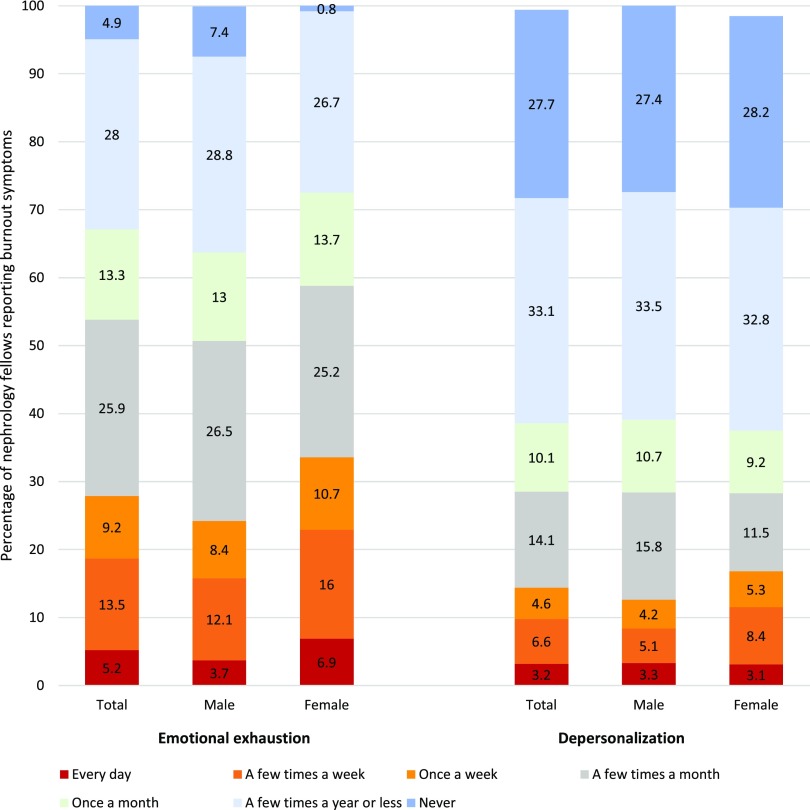

On the two-item burnout question items, emotional exhaustion more than once weekly and depersonalization more than once weekly were reported by 28.0% and 14.4% of the fellows, respectively (Figure 1, Table 2). This yielded a burnout prevalence of 30.0% among the respondents. On evaluating for depressive symptoms, depressed mood and anhedonia were identified in 31.1% and 23.9% of the fellows, respectively; 35.4% of the respondents were positive for depressive symptoms.

Figure 1.

Burnout symptoms reported by nephrology fellows were more frequent in the female as compared to the male gender. “Once a week” or more frequently to either item indicates burnout.

Table 2.

Burnout and emotional well being among surveyed first- and second-year nephrology fellows in the United States (n=347)

| Study Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Burnout—emotional exhaustion | |

| Every day | 18 (5.2) |

| A few times a week | 47 (13.5) |

| Once a week | 32 (9.2) |

| A few times a month | 90 (25.9) |

| Once a month | 46 (13.3) |

| A few times a year or less | 97 (28.0) |

| Never | 17 (4.9) |

| Missing | 0 |

| Burnout—depersonalization | |

| Every day | 11 (3.2) |

| A few times a week | 23 (6.6) |

| Once a week | 16 (4.6) |

| A few times a month | 49 (14.1) |

| Once a month | 35 (10.1) |

| A few times a year or less | 115 (33.1) |

| Never | 96 (27.7) |

| Missing | 2 (0.6) |

| Burnout—present/absent | |

| Burnout present | 104 (30.0) |

| Burnout absent | 243 (70.0) |

| Missing | 0 |

| Depressed mood (feeling down) | |

| Yes | 108 (31.1) |

| No | 238 (68.6) |

| Missing | 1 (0.3) |

| Anhedonia (little interest) | |

| Yes | 83 (23.9) |

| No | 263 (75.8) |

| Missing | 1 (0.3) |

| Positive for depressive symptoms | 123 (35.4) |

| Negative for depressive symptoms | 223 (64.3) |

| Missing | 1 (0.3) |

| Positive influence | |

| Every day | 61 (17.6) |

| A few times a week | 90 (25.9) |

| Once a week | 39 (11.2) |

| A few times a month | 78 (22.5) |

| Once a month | 33 (9.5) |

| A few times a year or less | 38 (11.0) |

| Never | 8 (2.3) |

| Missing | 0 |

| Program leadership | |

| Strongly agree | 125 (36.0) |

| Agree | 136 (39.2) |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 52 (15.0) |

| Disagree | 22 (6.3) |

| Strongly disagree | 12 (3.5) |

| Missing | 0 |

| Work-life balance | |

| Very satisfied | 55 (15.9) |

| Somewhat satisfied | 103 (29.7) |

| Neutral | 82 (23.6) |

| Somewhat dissatisfied | 71 (20.5) |

| Very dissatisfied | 35 (10.1) |

| Missing | 1 (0.3) |

| Social support | |

| All of the time | 138 (39.8) |

| Most of the time | 119 (34.3) |

| Some of the time | 53 (15.3) |

| A little of the time | 29 (8.4) |

| None of the time | 7 (2.0) |

| Missing | 1 (0.3) |

| Overall quality of life | |

| As good as it can be | 92 (26.5) |

| Somewhat good | 141 (40.6) |

| Neutral | 66 (19.0) |

| Somewhat bad | 37 (10.7) |

| As bad as it can be | 9 (2.6) |

| Missing | 2 (0.6) |

| Career satisfaction | |

| Definitely yes | 114 (32.9) |

| Probably yes | 140 (40.3) |

| Not sure | 44 (12.7) |

| Probably no | 31 (8.9) |

| Definitely no | 16 (4.6) |

| Missing | 2 (0.6) |

| Disruptive behavior | |

| Daily | 5 (1.4) |

| Weekly | 13 (3.7) |

| 1–2 times per month | 36 (10.4) |

| 1–5 times per year | 101 (29.1) |

| Never | 191 (55.0) |

| Missing | 1 (0.3) |

About half of the fellows agreed that their work had a positive effect on their patients (54.8%). Three quarters of fellows identified strong leadership in their fellowship program (75.2%). Satisfactory work-life balance was noted by 69.2%, adequate social support by 89.3%, and good quality of life by 86.2% of the respondents. Career satisfaction and disruptive environment at work was reported by 73.2% and 44.7% of the fellows, respectively.

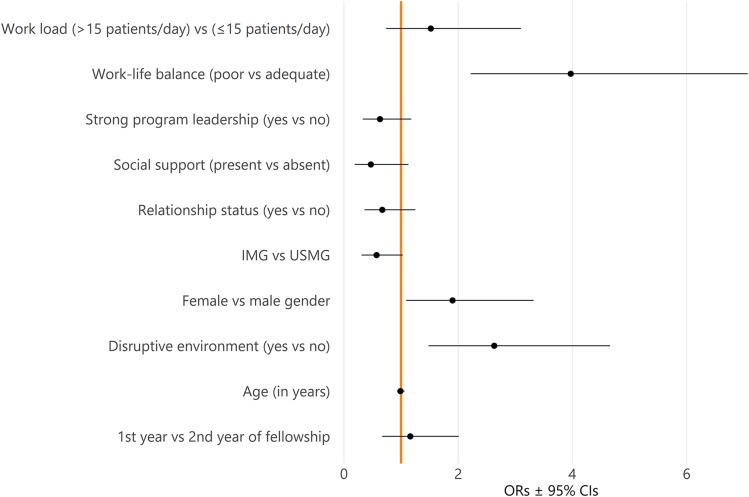

Characteristics Associated with Burnout and Depressive Symptoms

Demographic and emotional well being factors stratified by presence of burnout are presented in Supplemental Table 3. Fellows with burnout were more likely than those without burnout to be female, see >15 patients per weekday, have depressive symptoms, and report a disruptive environment at work. Fellows negative for burnout were statistically significantly more likely than those positive for burnout to identify a strong program leadership, appropriate work-life balance, adequate social support, good quality of life, and presence of career satisfaction. Multivariable logistic regression analysis revealed poor work-life balance (odds ratio [OR], 3.97; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.22 to 7.07; P<0.001), presence of a disruptive environment (OR, 2.63; 95% CI, 1.48 to 4.66; P=0.001), and female gender (OR, 1.90; 95% CI, 1.09 to 3.32; P=0.024) to be statistically significantly associated with burnout (Figure 2, Supplemental Table 4). Because there was a sizable number of fellows with depressive symptoms, a multivariable logistic regression analysis was also performed to identify factors associated with depressive symptoms (Supplemental Table 5). Presence of social support (OR, 0.08; 95% CI, 0.03 to 0.24; P<0.001), adequate work-life balance (OR, 0.17; 95% CI, 0.10 to 0.31; P<0.001), and strong program leadership (OR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.24 to 0.88; P=0.018) were statistically significantly associated with depressive symptoms.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of personal and work-related factors showing poor work-life balance, female gender and presence of disruptive environment to be significantly associated with burnout in United States adult nephrology fellows.

Discussion

The need to recognize and address physician burnout to improve the joy of nephrology practice has been recently emphasized.26 Clinical workload, administrative burden in dialysis care, and electronic medical records (EMRs) at multiple sites were speculated to be some of the drivers of burnout in nephrology attendings.26 While going through the rigors of medical training, nephrology fellows provide care to patients with medically complex issues and commonly work long hours in a consultant role to the primary medical team.6 We expected the burnout prevalence among nephrology fellows to be similar or even worse than that among medicine residents (45.2%–60.3% prevalence) when measured in a questionnaire similar to ours.4,27 In this first study of burnout in a national sample of nephrology fellows in the United States, the prevalence of burnout (30.0%) was, importantly, much lower in comparison with that in medicine residents. A similar survey of hematology-oncology fellows in 2013 revealed a burnout prevalence of 34.1%, which is closer but still higher than our study results.28 The multi-institutional random sample of nephrology fellows with almost equal distribution between first- and second-year fellows and representativeness of the United States nephrology fellow pool improves the generalizability of our findings.8 We designed the survey from validated instruments in the research literature, thus ensuring validity to a large extent. Although our study design precludes any conclusion on how burnout among nephrology fellows is different when compared with other internal medicine subspecialties, our findings do warrant further studies into this concerning burden affecting physicians in training.

We sought to speculate on why the burnout prevalence rate in our study was lower than expected by looking at the study methodology and findings. The survey was distributed toward the end of the academic year when clinical workload may be more efficiently handled, as compared with the start of the year, due to familiarity with the health system processes and enhanced medical knowledge. Improved seasonal affective symptoms or a secured employment after graduation may have also affected our study results. Nephrology fellowship programs are unique in having a higher proportion of IMGs.8 We did not find IMGs to have greater burnout than USMGs, possibly due to low educational debts from their home countries and resilience from navigating the competitive application process for training and work-related acculturation, although cultural differences and visa restrictions to securing a job may add to emotional distress.4 Many fellows were in a relationship and indicated having good social support, a known deterrent to burnout.20,22 About two thirds of the responding fellows had applied to another specialty besides nephrology, a finding in line with a 2015 report where 59% of the nephrology fellows applied simultaneously to another specialty.29 In our study, we did not find a difference in burnout prevalence between fellows who applied only to nephrology or a second specialty, suggesting a complex interplay between work-related and individual factors in causing burnout. Interestingly, we also found social support to be negatively associated with depressive symptoms. Promoting a culture of support from faculty, cofellows, staff, and family during physician training is likely to help decrease burnout and enhance resilience.22 Strong program leadership reported by many fellows in our survey may have lowered the burnout prevalence because an effective leader who can engage and inspire physicians has a negative effect on burnout.30 Nephrology program directors form a cohesive group, striving to improve the educational experiences of the fellows, streamline the fellowship application and matching process, and enhancing interest in nephrology in close collaboration with the ASN Workforce and Training Committee.6 Furthermore, a national survey of United States physicians reported that burnout prevalence in 2017 may actually be decreasing when compared with 2011, although work satisfaction continues to be low.1

We identified factors associated with burnout in nephrology fellows, although causality could not be established due to the cross-sectional design of our study. We found female nephrology fellows were more likely to experience burnout than their male colleagues, an observation also reported among residents and attendings. Our finding may possibly be explained by under-reporting by males, perceived lack of control over work schedule, patients having different expectations from female versus male physicians, or more work-home conflicts by female as compared with their male counterparts.31–34 Low satisfaction with work-life balance was associated with burnout in our survey and other studies in residents and attendings.4,34,35 This is especially relevant to the field of nephrology because having an adequate lifestyle and work-life balance is important in influencing career decisions.36 Similar to our findings, the 2017 ASN Nephrology Fellow Survey reported 17% of second-year fellows had poor or very poor work-life balance.9 We could not identify the reason behind the perception of poor work-life balance. Large case workload, as expected, was associated with burnout in bivariate analysis, possibly due to the burden of patient interaction, long work hours, and increased documentation requirements.37 The effect of work-related factors such as work hours, workload, pace, working conditions, and EMR documentation—especially at home (“pajama time”)—on burnout need to be studied.6,38–40 Presence of disruptive behavior at work was strongly associated with burnout in our survey. Disruptive behavior—actions that violate the perpetrator’s standard of respectful behavior and results in a perceived threat to the victim (or witness)—was witnessed by 71% of physicians in a 2011 survey commonly in the surgical, emergency room, and intensive-care-unit settings.41,42 Because nephrologists commonly collaborate with physicians in multiple medical and surgical settings in a consultant role, it is possible that nephrology fellows are exposed to disruptive behaviors. Our survey could not delineate if the disruptive behaviors originated from patients or other health care providers, or whether it was physical or psychologically traumatic. The high proportion of IMGs in nephrology fellowship programs may possibly expose them to racist behaviors by patients, thus contributing to workplace disruption.43 The psychologic stress of experiencing or witnessing the disruptive behavior and the fear of a future similar event may lead to burnout.44

Concerning findings in our survey were that 35.4% of fellows reported depressive symptoms and about a quarter of the nephrology fellows reported career dissatisfaction. We used the two-item Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders questionnaire that inquires about the presence or absence of depressed mood and anhedonia in the past month. A positive (“yes”) answer to either of these questions constitutes a positive screen for depression (i.e., positive for depressive symptoms) and has a sensitivity of 97% and specificity of 57%, respectively, for diagnosing major depression.16 Our finding is in line with 2015 meta-analysis data that showed prevalence of depressive symptoms to be 28.8% (95% CI, 25.3% to 32.5%) among resident physicians and surgeons.45 A positive screening result for depression is of major concern because this requires evaluation with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 or direct psychiatric interview to diagnose major depression.46 Prompt psychiatric involvement is needed in an attempt to prevent self-harm, especially as medical trainees do not necessarily seek help in depression due to guilt or shame in pursuing mental health services.47 Some experts propose that burnout is a depressive symptom and that prolonged period of exposure to severe burnout stressors at work may lead to depression.48 Career dissatisfaction is also of concern because it is associated with physician burnout.34 In a survey of >6500 physicians in the United States, nephrology ranked 39 (out of 42) in career satisfaction, which correlated with long work hours.49 A 2011 survey by Shah et al.38 found that approximately 16% of the 204 responding nephrology fellows were slightly or not at all satisfied with their career choice, especially IMGs or those who indicated nephrology not to be their first career choice. Fellows who identified positively for burnout in our study were more likely to have career dissatisfaction on bivariate analysis. Career dissatisfaction among nephrology fellows was reported to be due to poor income potential after fellowship, poor job opportunities, long work hours, and overall poor experiences during fellowship.38 Physicians dissatisfied with their career or specialization have indicated the desire to leave medical practice, which highlights the need to look into career dissatisfaction to maintain a nephrology workforce for the future.34

Our study has important implications for nephrology fellowship program directors and teaching faculty members who make concerted efforts to ensure fellow well being.28,50–53 Fellowship programs need to implement steps to minimize burnout, identify trainees at high risk of burnout, and provide fellow support to achieve work satisfaction and high-quality learning experiences throughout training (Table 3). Our study has limitations because we are unsure how many fellows received the survey due to email addresses being inactive or behind institutional firewalls. Survey fatigue may have affected our survey results as suggested by the missing values.54 However, the response rate in our study was similar to the 2017 ASN survey.9 Although we have shown that our study sample is reasonably well representative of the nephrology fellow pool, we do not have the complete data on the nonresponders and we could not fully account for this bias. Although we cannot exclude the possibility that nonresponders may have more burnout, the participants were not aware that the ASN survey included questions on burnout and well being because this was not mentioned in the cover letter or consent form. Our study was not designed to identify the drivers of burnout and we did not evaluate whether fellows’ schedules, night calls, or EMR use were associated with burnout. We used the validated two-item burnout from the MBI to identify burnout. Due to the large variability in prevalence of physician burnout reported (from 0% to 80.5%) with various questionnaire instruments and between different specialties, there exists an opinion whether the two items (emotional exhaustion and depersonalization) can reliably assess burnout among physicians.55,56 We evaluated the fellows for depressive symptoms but were unable to offer support or resources to those affected due to anonymous data collection.

Table 3.

Potential strategies to address burnout and depressive symptoms in nephrology training programs

| Potential Strategy |

|---|

| Support from program and organizational leadership: |

| Program directors need to be cognizant of the national and local trends and risk factors for burnout and depressive symptoms among physicians in training. |

| Programs should emphasize the importance of personal and professional well being at orientation and offer support throughout training. |

| Prioritizing work-life balance may be achieved by review of work hours, patient load, documentation needs, EMR responsibilities, work environment, call rooms, inpatient and outpatient rotations, and collaborating with fellows in creating work schedules. |

| Other strategies to enhance work-life integration such as mentoring programs, leadership training, promoting physical health and diet, and offering personal self-care tools to manage work and stress (such as time management, limiting EMR work at home) may be needed in fellowship programs. |

| Commitment from national organizations such as ASN, NKF, and the American College of Physicians to address physician burnout and emotional distress is highly encouraging. |

| Assessment: |

| Periodic assessment of burnout through the MBI or other validated surveys such as the Mini-Z in collaboration with the institution’s graduate medical education office can help identify and track longitudinal trends in well being, while identifying solutions at the personal level, workplace, or training environment based on available resources. |

| Academic curriculum: |

| Fellowship curriculum should incorporate sessions on emotional well being, financial planning, clinical expectations and practice, and responsibilities as medical director to allow a smooth transition into the attending role where burnout may be higher. |

| Training in palliative care and end-of-life discussions in nephrology may reduce burnout and fellows by empowering them with essential communication skills. |

| Addressing clinical workload: |

| Interventions—such as having nurse practitioners, nephrology hospitalists, change in overnight call—need to be studied as each strategy may produce different results in a program. |

| Access to mental health support: |

| Prompt access to confidential resources such as counselor or psychologist support while fostering a culture of social support and destigmatization is essential to prevent, identify, and treat depressive symptoms early, when present. |

| Addressing disruptive work environment: |

| Disruptive work environment needs to be addressed through program directors who serve as a liaison between fellows and hospital administration. |

| Hospital should adopt zero tolerance for any kind of violence in the workplace and promote confidential reporting in addressing workplace issues, while providing physicians with tools for coping and enhancing resilience. |

About a third of nephrology fellows in the United States experienced burnout and depressive symptoms. Future research studies need to evaluate nephrology fellows for burnout using questionnaires such as the full-length MBI, Mini-Z, or Copenhagen Burnout Inventory longitudinally or using qualitative research methods to study the prevalence and drivers of burnout in training.57 Further research needs to measure the burden of depressive symptoms in nephrology fellows and identify factors (including burnout) that could result in serious mental health problems and major depression. Burnout in nephrology fellows—especially that perceived by female physicians and due to disruption in work environment or poor work-life balance—need to be further explored to evaluate causality and develop targeted efforts (e.g., by ensuring reasonable workload, constructive and supportive program leadership, and adequate social support) to enhance the educational experience and emotional well being of nephrology fellows.

Disclosures

Mr. Pivert is an employee of the ASN Alliance for Kidney Health. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This study was supported by the Division of Nephrology and Hypertension, University of Vermont for purchase of the questionnaire instrument. Travel support to Dr. Agrawal was provided by the Teaching Academy at the Larner College of Medicine, University of Vermont.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the surveyed physicians for their participation. They also thank Alan Howard (University of Vermont) for biostatistical support, Dr. Robert W. Rope (Oregon Health & Science University), the ASN Workforce and Training Committee (chaired by Dr. Scott J. Gilbert, Tufts Medical Center), Edward Salsberg, Master of Public Administration, the NKF Education Committee (chaired at the time of the study by B.G.J., Johns Hopkins University), Dr. Shaden T. Eldakar-Hein (University of Vermont), and Dr. Jeffrey S. Berns (University of Pennsylvania) for critical review of the questionnaire, as well as Dr. Richard J. Solomon (University of Vermont) for financial support.

An abstract of this work was presented in part at the NKF’s 2019 Spring Clinical Meeting.

All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript. Dr. Agrawal was responsible for conception, study design, data analysis, interpretation, drafting, analysis, and was accountable for the work and accepts all responsibilities. Dr. Plantinga and Dr. Abdel-Kader were responsible for data analysis, interpretation, drafting, and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Mr. Pivert was responsible for acquisition of study data, editing, and figure design. Dr. Provenzano was responsible for conception of the study and study design. Dr. Soman, Dr. Choi, and Dr. Jaar were responsible for conception of the study, study design, interpretation, and editing.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2019070715/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Table 1. Questions on depressive symptoms and emotional well-being in the survey.

Supplemental Table 2. Comparison of demographic characteristics of responders and non-responders.

Supplemental Table 3. Parameters stratified by burnout status.

Supplemental Table 4. Association of characteristics with burnout among responding US nephrology fellows.

Supplemental Table 5. Multivariable logistic regression model for predictors of depressive symptoms.

References

- 1.Shanafelt TD, West CP, Sinsky C, Trockel M, Tutty M, Satele DV, et al.: Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life integration in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2017. Mayo Clin Proc 94: 1681–1694, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH: Executive leadership and physician well-being: Nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc 92: 129–146, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, West CP, Sinsky CA: Potential impact of burnout on the US physician workforce. Mayo Clin Proc 91: 1667–1668, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.West CP, Shanafelt TD, Kolars JC: Quality of life, burnout, educational debt, and medical knowledge among internal medicine residents. JAMA 306: 952–960, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peckham C: Medscape nephrologist lifestyle report. Medscape, New York, NY, 2017. Available at: https://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/lifestyle/2017/nephrology#page=2. Accessed April 30, 2019

- 6.Parker MG, Ibrahim T, Shaffer R, Rosner MH, Molitoris BA: The future nephrology workforce: Will there be one? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6: 1501–1506, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jhaveri KD, Sparks MA, Shah HH, Khan S, Chawla A, Desai T, et al.: Why not nephrology? A survey of US internal medicine subspecialty fellows. Am J Kidney Dis 61: 540–546, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Accreditation council for graduate medical education data resource book 2017-2018. Available at: https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/PublicationsBooks/2017-2018_ACGME_DATABOOK_DOCUMENT.pdf. Accessed April 18, 2019.

- 9.Quigley L, Salsberg E, Mehfoud N, Collins A: Report on the 2017 Survey of Nephrology Fellows. Washington, DC, American Society of Nephrology, 2017. Available at: https://www.asn-online.org/education/training/workforce/Nephrology_Fellow_Survey_Report_2017.pdf. Accessed June 28, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown RS: Is nephrology fellowship training on the right track? Am J Kidney Dis 60: 343–346, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferris M, Iglesia E, Ko Z, Amamoo A, Mahan J, Desai T, et al.: Wanted: Pediatric nephrologists! - why trainees are not choosing pediatric nephrology. Ren Fail 36: 1340–1344, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG: Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 42: 377–381, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP: Maslach burnout inventory manual, 3rd Ed., Palo Alto, CA, Consulting Psychologists Press, 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 14.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Satele DV, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD: Concurrent validity of single-item measures of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization in burnout assessment. J Gen Intern Med 27: 1445–1452, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aiken LH, Patrician PA: Measuring organizational traits of hospitals: The Revised Nursing Work Index. Nurs Res 49: 146–153, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whooley MA, Avins AL, Miranda J, Browner WS: Case-finding instruments for depression. Two questions are as good as many. J Gen Intern Med 12: 439–445, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maslach C, Jackson SE: The measurement of experienced burnout. J Organ Behav 2: 99–113, 1981 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps GJ, Russell T, Dyrbye L, Satele D, et al.: Burnout and career satisfaction among American surgeons. Ann Surg 250: 463–471, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosenstein AH: Original research: Nurse-physician relationships: Impact on nurse satisfaction and retention. Am J Nurs 102: 26–34, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hardeman RR, Przedworski JM, Burke SE, Burgess DJ, Phelan SM, Dovidio JF, et al.: Mental well-being in first year medical students: A comparison by race and gender: A report from the medical student change study. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 2: 403–413, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nesbitt H: American Society of Nephrology | fellows - in-training exam. Available at: https://www.asn-online.org/education/training/fellows/ite.aspx. Accessed November 7, 2019

- 22.Dyrbye L, Shanafelt T: A narrative review on burnout experienced by medical students and residents. Med Educ 50: 132–149, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD: Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med 283: 516–529, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bianchi R, Schonfeld IS, Laurent E: Burnout-depression overlap: A review. Clin Psychol Rev 36: 28–41, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahola K, Hakanen J, Perhoniemi R, Mutanen P: Relationship between burnout and depressive symptoms: A study using the person-centred approach. Burn Res 1: 29–37, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams AW: Addressing physician burnout: Nephrologists, how safe are we? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 325–327, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dyrbye LN, Burke SE, Hardeman RR, Herrin J, Wittlin NM, Yeazel M, et al.: Association of clinical specialty with symptoms of burnout and career choice regret among US resident physicians. JAMA 320: 1114–1130, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shanafelt TD, Raymond M, Horn L, Moynihan T, Collichio F, Chew H, et al.: Oncology fellows’ career plans, expectations, and well-being: Do fellows know what they are getting into? J Clin Oncol 32: 2991–2997, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ross MJ, Braden G; ASN Match Committee: Perspectives on the nephrology match for fellowship applicants. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 1715–1717, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shanafelt TD, Gorringe G, Menaker R, Storz KA, Reeves D, Buskirk SJ, et al.: Impact of organizational leadership on physician burnout and satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc 90: 432–440, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Purvanova RK, Muros JP: Gender differences in burnout: A meta-analysis. J Vocat Behav 77: 168–185, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 32.McMurray JE, Linzer M, Konrad TR, Douglas J, Shugerman R, Nelson K: The work lives of women physicians results from the physician work life study The SGIM Career Satisfaction Study Group. J Gen Intern Med 15: 372–380, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Linzer M, Harwood E: Gendered expectations: Do they contribute to high burnout among female physicians? J Gen Intern Med 33: 963–965, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dyrbye LN, Varkey P, Boone SL, Satele DV, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD: Physician satisfaction and burnout at different career stages. Mayo Clin Proc 88: 1358–1367, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Glasheen JJ, Misky GJ, Reid MB, Harrison RA, Sharpe B, Auerbach A: Career satisfaction and burnout in academic hospital medicine. Arch Intern Med 171: 782–785, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dorsey ER, Jarjoura D, Rutecki GW: Influence of controllable lifestyle on recent trends in specialty choice by US medical students. JAMA 290: 1173–1178, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Elliott DJ, Young RS, Brice J, Aguiar R, Kolm P: Effect of hospitalist workload on the quality and efficiency of care. JAMA Intern Med 174: 786–793, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shah HH, Jhaveri KD, Sparks MA, Mattana J: Career choice selection and satisfaction among US adult nephrology fellows. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 1513–1520, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Elmariah H, Thomas S, Boggan JC, Zaas A, Bae J: The burden of burnout. Am J Med Qual 32: 156–162, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sinsky C, Colligan L, Li L, Prgomet M, Reynolds S, Goeders L, et al.: Allocation of physician time in ambulatory practice: A time and motion study in 4 specialties. Ann Intern Med 165: 753–760, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Villafranca A, Fast I, Jacobsohn E: Disruptive behavior in the operating room: Prevalence, consequences, prevention, and management. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 31: 366–374, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sanchez LT: Disruptive behaviors among physicians. JAMA 312: 2209–2210, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen PG, Auerbach DI, Muench U, Curry LA, Bradley EH: Policy solutions to address the foreign-educated and foreign-born health care workforce in the United States. Health Aff (Millwood) 32: 1906–1913, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Portoghese I, Galletta M, Leiter MP, Cocco P, D’Aloja E, Campagna M: Fear of future violence at work and job burnout: A diary study on the role of psychological violence and job control. Burn Res 7: 36–46, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mata DA, Ramos MA, Bansal N, Khan R, Guille C, Di Angelantonio E, et al.: Prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms among resident physicians: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 314: 2373–2383, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.American Psychiatry Association: Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder, Third Edition. 2010. Available at: https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/mdd.pdf. Accessed May 3, 2019

- 47.Guille C, Speller H, Laff R, Epperson CN, Sen S: Utilization and barriers to mental health services among depressed medical interns: A prospective multisite study. J Grad Med Educ 2: 210–214, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bianchi R, Schonfeld IS, Laurent E: Physician burnout is better conceptualised as depression. Lancet 389: 1397–1398, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leigh JP, Tancredi DJ, Kravitz RL: Physician career satisfaction within specialties. BMC Health Serv Res 9: 166, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Linzer M, Poplau S, Babbott S, Collins T, Guzman-Corrales L, Menk J, et al.: Worklife and wellness in academic general internal medicine: Results from a national survey. J Gen Intern Med 31: 1004–1010, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Salles A, Liebert CA, Greco RS: Promoting balance in the lives of resident physicians: A call to action. JAMA Surg 150: 607–608, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Melamed ML, Campbell KN, Nickolas TL: Resizing nephrology training programs: A call to action. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 1718–1720, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Privitera MR: Organizational contributions to healthcare worker (HCW) burnout and workplace violence (WPV) overlap: Is this an opportunity to sustain prevention of both? Health 08: 531–537, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sullivan GM, Artino AR Jr: How to create a bad survey instrument. J Grad Med Educ 9: 411–415, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schwenk TL, Gold KJ: Physician burnout-A serious symptom, but of what? JAMA 320: 1109–1110, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rotenstein LS, Torre M, Ramos MA, Rosales RC, Guille C, Sen S, et al.: Prevalence of burnout among physicians: A systematic review. JAMA 320: 1131–1150, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dyrbye LN, Clinic M, Meyers D, Ripp J, Dalal N, Bird SB, et al. : A pragmatic approach for organizations to measure health care professional well-being. NAM Perspect 2018. doi:10.31478/201810b [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.