Abstract

The total synthesis of principinol D, a rearranged kaurane diterpenoid, is reported. This grayanane natural product is constructed via a convergent fragment coupling approach, wherein the central seven-membered ring is synthesized at a late stage. The bicyclo[3.2.1]octane fragment is accessed by a Ni-catalyzed α-vinylation reaction. Strategic reductions include a diastereoselective SmI2-mediated ketone reduction with PhSH and a new protocol for selective ester reduction in the presence of ketones. The convergent strategy reported herein may be an entry point to the larger class of kaurane diterpenoids.

The grayanane diterpenoids—well-known as the active components in “mad honey” due to inhibition of voltage-gated sodium ion channels1—have recently been identified as structurally novel allosteric inhibitors of carbonic anhydrases2 and phosphatases.3 Due to the ubiquity of various subtypes of these molecular targets, potential therapeutic development could span numerous different disease areas from neurological dysfunction to cancer.4,5

Grayananes are among a broader class of rearranged kauranes that also includes gibberellanes and 6,7-seco-kauranes (Figure 1A). The tetracyclic diterpenoid grayananes are formed by rearrangement of the kaurane 6,6-A/B ring system to a 5,7-ring system.6 The kauranes are derived from rearrangement and cyclization of pimaranes via the beyeranes.7,8 The first total synthesis of (±)-kaurene was completed in 1962 by Ireland and co-workers,9 and in recent years several groups have completed elegant syntheses of members of this broader class employing a diverse array of synthetic strategies.10 Nevertheless, much of the >1000 kaurane diterpenoids that have been isolated remain inaccessible by previously reported synthetic approaches.

Figure 1.

(A) Precursors and derivatives of the kaurane diterpenes. (B) Retrosynthetic analysis of principinol D (l).

Synthetic efforts toward the grayananes have been especially limited11 despite their compelling biological activities.3,12 To address the stereochemical complexities of these compounds, linear cyclization strategies have been employed previously.11c We speculated that a convergent retrosynthetic strategy, which isolates the two main constellations of stereocenters, would yield a laboratory route that could enable synthesis of grayanane analogs. Herein, we report the first total synthesis of the grayanane principinol D (l).

Similar to other grayanane diterpenoids, the principinols possess a highly oxidized tetracyclic framework, including a bicyclo[3.2.1]octane ring system.13 As can be seen in Figure 1B, principinol D (l) has four stereocenters proximal to the left-most five-membered ring that are separated spatially from an additional five stereocenters that decorate the bicyclo[3.2.1]octane ring system. In order to provide access to structurally diverse analogs, we designed a convergent strategy wherein two fragments would be joined to assemble the core skeleton and simultaneously merge the two sets of stereocenters. This topological simplification to mark external rings for preservation differs significantly from prior work in the grayanane class, but is a powerful strategy in diterpenoid synthesis.14

We planned to utilize two robust C–C bond-forming reactions to merge the fragments, as this would maximize success for creating derivatives for SAR investigations: fragment union via a 1,2-addition reaction between a cyclopentyl fragment (4) and a bicyclo[3.2.1]octane fragment (3), and subsequent reductive cyclization using SmI2. Dissection of the bicyclic fragment by an exendo bond using a Ni-catalyzed α-vinylation reaction would reveal a six-membered ring that could be obtained by vicinal difunctionalization of cyclohexenone. Compound 4 was readily obtained from the known compound 515 by dithiane addition, MOM protection, and dithiane deprotection which proceeded in 55% yield over 3 steps (not depicted; see Supporting Information for details).

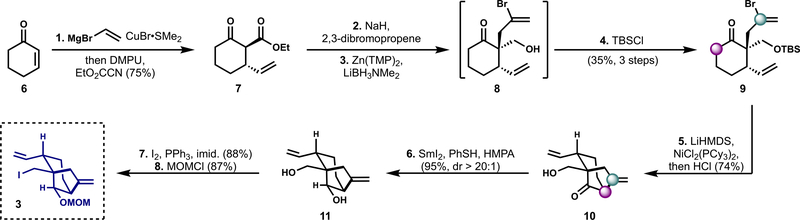

The synthesis of bicyclo[3.2.1]octane fragment 3 began with a vicinal difunctionalization of cyclohexenone with vinylmagnesium bromide in the presence of DMPU and catalytic CuBr SMe2, followed by trapping with Mander’s reagent (Scheme 1).16,17 β-Ketoester 7 underwent allylation with 2,3-dibromopropene. It was hoped that reduction of the ester could occur in the presence of the ketone in order to eliminate unnecessary redox fluctuations.18 Common protocols that protect the ketone in situ via nucleophilic addition with metal amides19 or phosphines20 failed. Likewise, initial efforts masking the ketone as an enolate (LiHMDS, KHMDS, NaHMDS, or LDA) and treatment with a reductant (LiAlH4, DIBAL-H, AlH3, LiBH4, or LiEt3BH) led to basemediated decomposition.21 More mild and selective conditions were identified, wherein an enolate formed by deprotonation with the weaker base Zn(TMP)2 underwent reduction with commercially available LiBH3NMe222 to form the base-sensitive keto-alcohol 8. It is our expectation that this procedure will find additional application in the selective reduction of esters in the presence of enolizable carbonyl compounds, especially in the case of base-sensitive substrates. Protection of the resultant primary alcohol as the TBS ether provided the vinylation precursor 9 in 35% yield as a single diastereomer over 3 steps.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Bicyclo[3.2.l] octane Fragment Coupling Partner 3a.

a(l) CH2CHMgBr (1.1 equiv), CuBr SMe2 (0.1 equiv), DMPU (3.5 equiv), EtO2CCN (1.1 equiv), THF (0.6 M), −50 → −72 → 23 °C, 6 h, 75%; (2) NaH (1.3 equiv), 2,3-dibromopropene (1.2 equiv), DMF (0.4 M), 0 → 23 °C, 13 h; (3) Zn(TMP)2 (1.1 equiv), LiBH3NMe2 (1.0 equiv), THF (0.1 M), 0 → 23 °C, 1 h; (4) TBSCl (5.0 equiv), imid. (10.0 equiv), DMAP (0.3 equiv), DMF (0.1 M), 40 °C, 16 h, 35% (3 steps); (5) LiHMDS (2.0 equiv), NiCl2(PCy3)2 (0.3 equiv), THF (0.2 M), −40 → 50 °C, 3 h, then 6 N HCl, 74%; (6) SmI2 (3.0 equiv), PhSH (6.0 equiv), HMPA (10.0 equiv), THF (0.1 M), 0 °C, 1 h, 95%, >20:1 dr; (7) I2 (1.5 equiv), PPh3 (2.0 equiv), imid. (4.0 equiv), C6H6/MeCN/CH2Cl2 (4:1:1, 0.2 M), 0 → 23 °C, 90 h, 88%; (8) MOMCl (5.0 equiv), i-Pr2NEt (5.0 equiv), CH2Cl2 (0.2 M), 0 → 23 °C, 72 h, 87%.

In order to form the bicycle 10 from the halide 9, a variety of α-vinylation substrates and conditions were investigated. We found that the analogous β-ketoester (not depicted, the product of step 2) was not a viable substrate for the vinylation reaction. This may be due to the preference for the ester-containing compound to adopt the chair conformation wherein the ester is axial and the allyl group is equatorial, thus disfavoring the formation of the C-vinylation product, which is only accessible for the conformation wherein the allyl group is axial. We hypothesized that replacing the ester with a larger substituent would predispose the intermediate to adopt the necessary chair conformer in which the allyl substituent is axial, and thus lead to higher degrees of C-vinylation—this is indeed what we observed. Vinylation was ultimately performed using NiCl2(PCy3)2 as a precatalyst and LiHMDS as base. These conditions proved to be more successful than either Pd-catalyzed conditions,23 wherein cross-coupling can be problematic on such 1,1-disubstituted alkenes, or Ni-catalyzed conditions employing NHC ligands as recently reported by Helquist.24

Following deprotection of the TBS-protected keto-alcohol, we required a diastereoselective reduction of ketone 10. Unfortunately, reduction with boron or aluminum hydrides (NaBH4, Et2BOMe/NaBH4, NaBH4/CeCl3, DIBAL, Al(O-i- Pr)3) produced predominantly the undesired diastereomer. With use of SmI2 in the presence of H2O the product was still disfavored (dr = 1:2). Addition of HMPA and PhSH,25 which may act as an H atom donor,26 provided the desired product in an excellent yield (95%, >20:1 dr). The use of HMPA was required for the reaction to proceed to full conversion, presumably because it increases the reduction potential of the samarium complex.27,28 After the development of this protocol, it was successfully employed in the context of a different natural product synthesis and found to be similarly effective for the reduction of 1,3-diketones.6 These modified conditions of classic SmI2-mediated thermodynamic reduction may find additional utility in multistep synthesis.

Conversion of the primary alcohol in the presence of a secondary alcohol to the primary alkyl iodide occurred smoothly by the Appel reaction using a trisolvent system of C6H6/MeCN/CH2Cl2 in a ratio of 4:1:1. It is noteworthy that this trisolvent system proved to be uniquely effective for this transformation: experiments with a single solvent or combinations thereof resulted in prohibitively low yields. After MOM protection of the remaining secondary alcohol, the bicycle 3 necessary for fragment coupling was obtained.

To link the two fragments, the racemic bicyclo[3.2.1]octane 3 was treated with tert-butyllithium, followed by addition of enantioenriched cyclopentyl aldehyde 4 (er = 93:7), which provided the adduct as a separable mixture of diastereomers in 5:5:1:1 dr with a combined yield of 62% (Scheme 2). Proceeding forward with the single desired diastereomer that was formed in 26% yield, protection of the secondary alcohol with MOMCl formed 12; due to the steric hindrance at this center, introduction of other protecting groups such as TBS and TES was not feasible. The allylic silyl ether could be converted to an enone, and selective oxidative cleavage of the monosubstituted alkene in the presence of the 1,1- disubstituted alkene afforded enone-aldehyde 13. To obtain the observed selectivity, DABCO was a key additive, whereas NMO, 2,6-lutidine, methanesulfonamide, and various two-step procedures were less effective.29

Scheme 2. Total Synthesis of Principinol D (l) via Fragment Coupling and Reductive Cyclizationa.

aReagents and conditions: (9) t-BuLi (2.0 equiv), pentane/Et2O (3:2, 0.1 M), −78 → 0 °C, 2.5 h, 62%, dr 5:5:1:1; (10) MOMCl (10 equiv), DMAP (2.2 equiv), i-Pr2NEt (15 equiv), (CH2Cl)2 (0.2 M), 80 °C, 17 h, 88%; (n) TBAF (5.0 equiv), THF (0.1 M), 23 °C, 3 h, 96%; (12) DMP (5.0 equiv), CH2Cl2 (0.1 M), 23 °C, 30 h, 79%; (13) OsO4 (0.1 equiv), DABCO (3.0 equiv), NaIO4 (3.0 equiv), THF/H2O (2:1, 0.01 M), 0 °C, 15 h, 84%; (14) SmI2 (25 equiv), H2O (2.6 equiv), THF (0.01 M), −72 → 0 °C, 2.5 h, 63%; (15) DMP (5.0 equiv), pyridine/CH2Cl2 (1:2, 0.07 M), 23 °C, 20 h, 92%; (16) Me3SiCH2Li (10 equiv), THF (0.01 M), 0 °C, 0.3 h, 87%; (17) Mn(dpm)3 (0.15 equiv), PhSiH3 (2.2 equiv), O2, EtOH (0.02 M), 23 °C, 1.5 h; (18) LiEt3BH (14 equiv), THF (0.01 M), 0 → 65 °C, 16 h, 52% over 2 steps; (19) 2 M H2SO4/1,4-dioxane (1:2, 0.01 M), 23 °C, 5 d, 78%.

At this stage, closure of the seven-membered ring using SmI2 was attempted.30,31 After extensive optimization, it was found that treatment of enone-aldehyde 13 with SmI2 in the presence of water provided the desired tetracycle 2 in 63% yield as a single diastereomer. The structure and stereochemistry of this compound were determined by NOESY NMR, and the absolute configuration was confirmed by X-ray crystallography.

After completion of the synthesis of the carbocyclic core structure 2, significant challenges remained: installation of the secondary alcohol at C3, alkene at C10, and tertiary alcohol at C16. Several sequences of events were investigated, and it was found that intermediate 14, prepared by oxidation of 2 using Dess-Martin periodinane buffered with pyridine, was a viable substrate to navigate chemoselectivity challenges. A selective olefination of the ketone on the seven-membered ring was attempted in the presence of the five-membered ring ketone. Standard olefination conditions (e.g., Wittig, Tebbe, Petasis, Nysted, etc.) were unable to form the desired exocyclic olefin. However, it was found that treatment with Me3SiCH2Li was efficient in producing Peterson adduct 15.32 Thus, the three sites (C3, C10, C16) were differentiated in a synthetically productive way.

Mukaiyama hydration of the exocyclic olefin with Mn(dpm)3, PhSiH3, and O2 installed the tertiary alcohol at C16. Reduction of cyclopentyl ketone 15 at C3 produced predominantly the undesired α-alcohol under most conditions that were attempted (e.g., DIBAL, LAH, NaBH4, NaBH4/CeCl3-7H2O, Na0, LiBH4, Zn(BH4)2, SmI2, etc.). Reaction with LiEt3BH resulted in the exclusive formation of the desired alcohol at C3. Upon heating, concomitant elimination of the Peterson adduct released the methylidene at C10, and the product was isolated as one diastereomer in 52% yield over 2 steps. Global MOM deprotection occurred smoothly using H2SO4 in 1,4-dioxane, furnishing principinol D (1). The NMR spectral data were identical to those reported.13

The work described herein represents the first total synthesis of principinol D (1) by a 19-step approach. This asymmetric synthesis features a convergent fragment coupling strategy, and a SmI2-mediated reductive cyclization to form the central seven-membered ring of the grayanane skeleton. In addition, α-vinylation conditions are reported to form the bicyclo[3.2.1]octane, as well as a diastereoselective SmI2- mediated reduction of a bicyclic ketone. Efforts toward the enantioselective synthesis of this fragment are ongoing. This synthetic route is expected to lead to laboratory access to a variety of derivatives, including ones which selectively act on phosphatases, carbonic anhydrases, or voltage-gated sodium ion channels; all are known targets of the grayananes.1–3

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Financial support was provided by Yale University, Sloan Foundation, Amgen, the NIH (5R01-GM118614), and the American Cancer Society. We are grateful for support through National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowships (A.T. and A.C.S.), a Ford Foundation Predoctoral Fellowship (A.C.S), and a Rudolph J. Anderson postdoctoral fellowship (Y.C.). Dr. Brandon Mercado is acknowledged for X-ray crystallographic analysis of compound 2.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/jacs.9b03751.

Detailed experimental procedures, X-ray diffraction, spectroscopic data for all new compounds including 1H and 13C NMR spectra (PDF)

Crystallographic data for 2 (CIF)

REFERENCES

- (1).(a) Koca AF; Koca I Poisoning by mad honey: A brief review. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2007, 45, 1315–1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gunduz A; Turedi S; Russell RM; Ayaz FA Clinical review of grayanotoxin/mad honey poisoning past and present. Clin. Toxicol. 2008, 46, 437–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Jansen SA; Kleerekooper I; Hofman ZL; Kappen IFP; Stary-Weinzinger A; van der Heyen MAG Grayanotoxin Poisoning: ‘Mad Honey Disease’ and Beyond. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2012, 12, 208–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Durdagi S; Scozzafava G; Vullo D; Sahin H; Kolayli S; Supuran CT Inhibition of mammalian carbonic anhydrases I-XIV with grayanotoxin III: solution and in silico studies. J. Enzyme Inhib.Med. Chem. 2014, 29, 469–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Li C-H; Zhang J-Y; Zhang X-Y; Li S-H; Gao J-M An overview of grayanane diterpenoids and their biological activities from the Ericaceae family in the last seven years. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 166, 400–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Regarding voltage-gated sodium ion channel applications, see:Stevens M; Peigneur S; Tytgat J Neurotoxins and their binding areas on voltage-gated sodium channels. Front. Pharmacol 2011, 2, 1–13.Bagal SK; Brown AD; Cox PJ; Omoto K; Owen RM; Pryde DC; Sidders B; Skerratt SE; Stevens EB; Storer RI; Swain NA Ion Channels as Therapeutic Targets: A Drug Discovery Perspective. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 593–624.Nardi A; Damann N; Hertrampf T; Kless A Advances in Targeting Voltage-Gated Sodium Channels with Small Molecules. ChemMed-Chem 2012, 7, 1712–1740.de Lera Ruiz M; Kraus RL Voltage-Gated Sodium Channels: Structure, Function, Pharmacology, and Clinical Indications. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 7093–7118.

- (5).For phosphatases as targets, see:Zhang S; Zhang ZY PTP1B as a Drug Target: Recent Developments in PTP1B Inhibitor Discovery. Drug Discovery Today 2007, 12, 373–381.Stuible M; Doody KM; Tremblay ML PTP1B and TC-PTP: regulators of transformation and tumorigenesis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2008, 27, 215–230.Lessard L; Stuible M; Tremblay ML The two faces of PTP1B in cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Proteins Proteomics 2010, 1804, 613–619. For carbonic anhydrases as targets, see:Supuran CT Carbonic anhydrases: novel therapeutic applications for inhibitors and activators. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2008, 7, 168.

- (6).For an example of a similar rearrangement in the justicanes, see:Elkin M; Scruse AC; Turlik A; Newhouse TR Computational and Synthetic Investigation of Cationic Rearrangement in the Putative Biosynthesis of Justicane Triterpenoids. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 1025–1029.

- (7).Breitmaier E Terpenes: Flavors, Fragrances, Pharmaca, Pheremones; Wiley-VCH: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- (8).Toyomasu T; Sassa T In Diterpenes in Comprehensive Natural Products II. Chemistry and Biology; Mander L, Liu H-W, Eds.; Newnes: 2010; Vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Bell RA; Ireland RE; Partyka RA The Total Synthesis of (±)-Kaurene. J. Org. Chem. 1962, 27, 3741–3744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).For examples, see:Gong J; Lin G; Sun W; Li C-C; Yang Z Total Synthesis of (±) Maoecrystal V. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 16745–16746.Cha JY; Yeoman JST; Reisman SE A Concise Total Synthesis of (−)-Maoecrystal Z. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 14964–14967.Peng F; Danishefsky SJ Total Synthesis of (±)-Maoecrystal V. J.Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 18860–18867.Cherney EC; Green JC; Baran PS Synthesis of ent- Kaurane and Beyerane Diterpenoids by Controlled Fragmentations of Overbred Intermediates. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 9019–9022.Yeoman JTS; Mak VW; Reisman SE A Unified Strategy to ent-Kauranoid Natural Products: Total Syntheses of (−)-Trichorabdal A and (−)-Longikaurin E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 11764–11767.Lu P; Gu Z; Zakarian A Total Synthesis of Maoecrystal V: Early-Stage C-H Functionalization and Lactone Assembly by Radical Cyclization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 14552–14555.Pan Z; Zheng C; Wang H; Chen Y; Li Y; Cheng B; Zhai H Total Synthesis of (±)-Sculponeatin N. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 216–219.Moritz BJ; Mack DJ; Tong L; Thomson RJ Total Synthesis of the Isodon Diterpene Sculponeatin N. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 2988–2991.Zheng C; Dubovyk I; Lazarski KE; Thomson R J. Enantioselective Total Synthesis of (−)-Maoecrystal V. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 17750–17756.Cernijenko A; Risgaard R; Baran PS 11-Step Total Synthesis of (−)-Maoecrystal V. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 9425–9428.Zhao X; Li W; Wang J; Ma D Convergent Route to ent-Kaurane Diterpenoids: Total Synthesis of Lungshengenin D and 1α,6α-Diacetoxy-ent-kaura- 9(11),16-dien-12–15-dione. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 2932–2935.He C; Hu J; Wu Y; Ding H Total Syntheses of Highly Oxidized ent-Kaurenoids Pharicin A, Pharicinin B, 7-O-Acetylpseurata C, and Pseurata C: A [5 + 2] Cascade Approach. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 6098–6101.

- (11).(a) Hamanaka N; Matsumoto T Partial Synthesis of Grayanotoxin. Tetrahedron Lett. 1972, 13, 3087–3090. [Google Scholar]; (b) Gasa S; Hamanaka N; Matsunaga S; Okuno T; Takeda N; Matsumoto T Relay Total Synthesis of Grayanatoxin II. Tetrahedron Lett. 1976, 17, 553–556. [Google Scholar]; (c) Kan T; Hosokawa S; Nara S; Oikawa M; Ito S; Matsuda F; Shirahama H Total Synthesis of (—)-Grayanotoxin III. J. Org. Chem. 1994, 59, 5532–5534. [Google Scholar]; (d) Borrelly S; Paquette LA Studies Directed to the Synthesis of the Unusual Cardiotoxic Agent Kalmanol. Enantioselective Construction of the Advanced Tetracyclic 7-Oxy-5,6-dideoxy Congener. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 727–740. [Google Scholar]; (e) Chow S; Kreβ C; Albaek N; Jessen C; Williams CM Determining a Synthetic Approach to Pierisformaside C. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 5286–5289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Li Y; Liu Y-B; Yu S-S Grayanoids from the Ericaceae family: structures, biological activities and mechanism of action. Phytochem. Rev 2013, 12, 305–325. [Google Scholar]

- (13).(a) Liu C-C; Lei C; Zhong Y; Gao L-X; Li J-Y; Yu MH Novel grayanane diterpenoids from Rhododendron principis. Tetrahedron 2014, 70, 4317–4322. [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhang M; Xie Y; Zhan G; Lei L; Shu P; Chen Y; Xue Y; Luo Z; Wan Q; Yao G; Zhang Y Grayanane and leucothane diterpenoids from the leaves of Rhododendron micranthum. Phytochemistry 2015, 117, 107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Urabe D; Asaba T; Inoue M Convergent Strategies in Total Syntheses of Complex Terpenoids. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 9207–9231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Compound 5 was obtained over 4 steps from commercially available 2-methylcyclopentane-1,3-dione; see: Huang D; Zhao Y; Newhouse TR Synthesis of Cyclic Enones by Allyl-Palladium-Catalyzed α,β-Dehydrogenation. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 684–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Mander LN; Sethi SP Regioselective synthesis of β- ketoesters from lithium enolates and methyl cyanoformate. Tetrahe- dron Lett. 1983, 24, 5425–5428. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Bruhn J; Heimgartner H; Schmid H 267. Die Cope- Umlagerung als Prinzip einer repetierbaren Ringerweiterung. Helv. Chim. Acta 1979, 62, 2630–2654. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Burns NZ; Baran PS; Hoffmann R W. Redox Economy in Organic Synthesis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 2854–2867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Barrios FJ; Springer BC; Colby DA Control of Transient Aluminum-Aminals for Masking and Unmasking Reactive Carbonyl Groups. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 3082–3085. and references therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Fujioka H; Yahata K; Kubo O; Sawama Y; Hamada T; Maegawa T Reversing the Reactivity of Carbonyl Functions with Phosphonium Salts: Enantioselective Total Synthesis of (+)-Cen- trolobine. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 12232–12235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).(a) Isobe K; Mohri K; Sano H; Taga J; Tsuda Y Chemoselective Reduction of β-Keto-esters to β-Keto-alcohols. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1986, 34, 3029–3032. [Google Scholar]; (b) Heinz U; Adams E; Klintz R; Welzel P 2-Tosyloxymethylcyclanones: Ring Size Dependence of Fragmentation Versus Intramolecular Alkylation. Tetrahedron 1990, 46, 4217–4230. [Google Scholar]; (c) Ye Q; Qu P; Snyder SA Total Syntheses of Scaparvins B, C, and D Enabled by a Key C–H Functionalization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 18428–18431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).(a) Fisher GB; Fuller JC; Harrison J; Alvarez SG; Burkhardt ER; Goralski CT; Singaram B Aminoborohydrides. 4. The Synthesis and Characterization of Lithium Aminoborohydrides: A New Class of Powerful, Selective, Air-Stable Reducing Agents. J. Org. Chem. 1994, 59, 6378–6385. [Google Scholar]; For a review on aminoborohydrides, see: Pasumansky L; Goralski CT; Singaram B Lithium Aminoborohydrides: Powerful, Selective, Air-Stable Reducing Agents. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2006, 10, 959–970. [Google Scholar]

- (23).For a review of transition-metal-catalyzed alkenylation reactions, see: Ankner T; Cosner CC; Helquist P Palladium- and Nickel- Catalyzed Alkenylation of Enolates. Chem. - Eur. J 2013, 19, 1858–1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Grigalunas M; Ankner T; Norrby P-O; Wiest O; Helquist P Ni-Catalyzed Alkenylation of Ketone Enolates under Mild Conditions: Catalyst Identification and Optimization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 7019–7022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Banwell MG; Hockless DCR; McLeod MD Chemoenzymatic total syntheses of the sesquiterpene (−)-patch- oulenone. New J. Chem. 2003, 27, 50–59. [Google Scholar]

- (26).(a) Mayer JM Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer: A Reaction Chemist’s View. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2004, 55, 363–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chciuk TV; Anderson WR Jr.; Flowers RA Proton- Coupled Electron Transfer in the Reduction of Carbonyls by Samarium Diiodide–Water Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 8738–8741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kolmar SS; Mayer JM SmI2(l·l2O)n Reduction of Electron Rich Enamines by Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 10687–10692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Chciuk TV; Anderson WR; Flowers RA Interplay between Substrate and Proton Donor Coordination in Reductions of Carbonyls by SmI2- Water Through Proton-Coupled Electron-Transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 15342–15352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Flowers RA II Mechanistic Studies on the Roles of Cosolvents and Additives in Samarium(II)-Based Reductions. Synlett 2008, 2008, 1427–1439. [Google Scholar]

- (28).Szostak M; Spain M; Procter DJ Recent advances in the chemoselective reduction of functional groups mediated by samarium- (II) iodide: a single electron transfer approach. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 9155–9183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Minato M; Yamamoto K; Tsuji J Osmium Tetraoxide Catalyzed Vicinal Hydroxylation of Higher Olefins by Using Hexacyanoferrate (III) Ion as a Cooxidant. J. Org. Chem. 1990, 55, 766–768. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Edmonds DJ; Johnston D; Procter DJ Samarium(II)- Iodide-Mediated Cyclizations in Natural Product Synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 3371–3403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Szostak M; Fazakerley NJ; Parmar D; Procter DJ Cross-Coupling Reactions Using Samarium (II) Iodide. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 5959–6039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Peterson DJA Carbonyl Olefination Reaction Using Silyl-Substituted Organometallic Compounds. J. Org. Chem. 1968, 33, 780–784. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.