Abstract

CCD photometric observations of 19 main-belt asteroids were obtained at the Center for Solar System Studies (CS3) from 2019 April to June.

The Center for Solar System Studies (CS3) has seven telescopes which are normally used for specific topic studies. The usual focus is on near-Earth asteroids, but when suitable targets are not available, Jovian Trojans and Hildas are observed. When a nearly full moon is too close to the primary targets being studied, targets of opportunity amongst the main-belt regions were selected.

Table I lists the telescopes and CCD cameras that were used to make the observations. Images were unbinned with no filter and had master flats and darks applied. The exposures depended upon various factors including magnitude of the target, sky motion, and Moon illumination.

Table I:

List of CS3 telescope/CCD camera combinations.

| Telescope | Camera |

|---|---|

| 0.30-m f/6.3 Schmidt-Cass | FLI Microline 100IE |

| 0.35-m f/9.1 Schmidt-Cass | FLI Microline 1001E |

| 0.35-m f/9.1 Schmidt-Cass | FLI Microline 1001E |

| 0.35-m f/9.1 Schmidt-Cass | FLI Microline 1001E |

| 0.35-m f/11 Schmidt-Cass | FLI Microline 1001E |

| 0.40-m f/10 Schmidt-Cass | FLI Proline 1001E |

| 0.50-m F8.1 R-C | FLI Proline 1001E |

Image processing, measurement, and period analysis were done using MPO Canopus (Bdw Publishing), which incorporates the Fourier analysis algorithm (FALC) developed by Harris (Harris et al., 1989). The Comp Star Selector feature in MPO Canopus was used to limit the comparison stars to near solar color. Night-tonight calibration was done using field stars from the CMC-15 or the ATLAS catalog (Tonry et al., 2018), which has Sloan griz magnitudes that were derived from the GAIA and Pan-STARR catalogs, among others. The authors state that systematic errors are generally no larger than 0.005 mag, although they can reach 0.02 mag in small areas near the Galactic plane. BVRI magnitudes were derived by Warner using formulae from Kostov and Bonev (2017). The overall errors for the BVRI magnitudes, when combining those in the ATLAS catalog and the conversion formulae, are on the order of 0.04–0.05 mag.

Even so, we found in most cases that nightly zero point adjustments for the ATLAS catalog to be on the order of only 0.02–0.03 mag were required during period analysis. There were occasional exceptions that required up to 0.10 mag. These may have been related in part to using unfiltered observations, poor centroiding of the reference stars, and not correcting for second-order extinction terms. Regardless, the systematic errors seem to be considerably less than other catalogs, which reduces the uncertainty in the results when analysis involves data from extended periods or the asteroid is tumbling.

In the lightcurve plots, the “Reduced Magnitude” is Johnson V corrected to a unity distance by applying −5*log (rΔ) to the measured sky magnitudes with r and Δ being, respectively, the Sun-asteroid and the Earth-asteroid distances in AU. The magnitudes were normalized to the phase angle given in parentheses using G = 0.15. The X-axis rotational phase ranges from −0.05 to 1.05.

The amplitude indicated in the plots (e.g. Amp. 0.23) is the amplitude of the Fourier model curve and not necessarily the adopted amplitude of the lightcurve.

For brevity, only some of the previously reported rotational periods may be referenced. A complete list is available at the lightcurve database (LCDB; Warner et al., 2009).

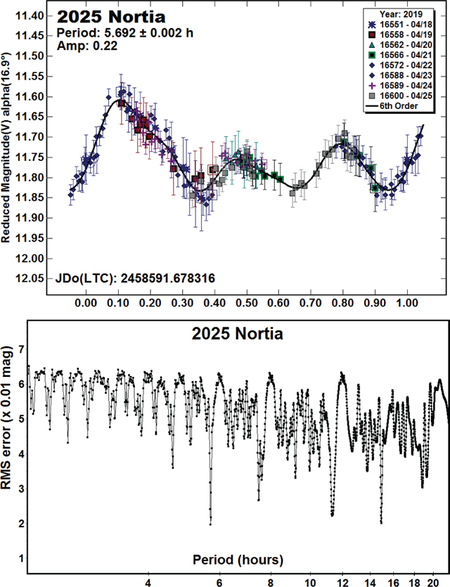

2025 Nortia.

The LCDB listed no previous rotation periods for this outer main-belt asteroid. Assuming an albedo of 0.057, the estimated diameter is 40 km. The lightcurve shows three maximums. This is unusual but possible with low amplitudes and phase angles (Harris et al., 2014).

2378 Pannekoek.

Previous results gave 5.943 h (Higgins, 2008) and 11.8806 h (Oey 2011 web), for this outer main-belt asteroid. Our results from 2019 show several aliases with our preference for P = 11.874 h even though the lightcurve is missing about 30% of a full rotation. This is based on the half-period plot showing the asymmetry of the full period solution. The spacing of extrema doesn’t seem right for the near 7.9 h solution, but because of the amplitude, an unusual shape cannot be formally excluded (Harris et al., 2014), especially when the period spectrum shows sharp RMS minimums near 6 and 8 hours.

2510 Shandong.

This inner main-belt asteroid has a diameter of about 9 km. Higgins and Goncalves (2007) found a period of 5.9463 h. Using a combination of dense and sparse lightcurve data, Hanus et al. (2013) found Psidereal = 5.94639 h and a preferred spin axis with ecliptic coordinates λ, β = (256°, 27°)

2778 Tangshan.

Rotational periods for this member of the Flora group near 3.46 h have been reported twice before (Behrend et al., 2018, Warner, 2004). The result found this year is in good agreement.

4160 Sabrina-John.

This appears to be the first rotation period for Sabrina-John, which is classified as a Vestoid (i.e., possibly a fragment off Vesta) with a diameter of about 7 km.

4892 Chrispollas.

This 8-km inner main-belt asteroid had no previously reported period in the LCDB. There may be good reason for that: the extremely long period that we report here. In our data, night-to-night runs showed almost no ascending or descending trend. Given limited telescope time for many, this might have led most observers to give up in lieu of working other targets that had better opportunities for success.

Our program is dedicated to working potentially long-period objects until it is certain that the data are “flat” (low amplitude) or at least an approximate estimate of the period can be found. Even so, it was not possible to follow this asteroid long enough to obtain a full lightcurve and so our result is based on the presumed monomodal lightcurve at the half-period (Harris et al., 2014). Even this lightcurve is incomplete and so the true error in the resulting full-period is probably larger than the formal value given here. Because of the long period and estimated diameter, this is a good candidate for tumbling (Pravec et al., 2014; 2005). There are some indications of this with at least two sessions falling below the Fourier curve.

(5267) 1991 MA.

Our result is about 0.15 h longer than previous results: Waszczak et al. (2015) and Zeigler et al. (2017). The former is a survey with a “dense sparse” data set. Zeigler et al. had two non-consecutive nights that produced a lightcurve that did not have full double coverage. For these reasons, we have high confidence in our result.

6310 Jankonke

is a Hungaria asteroid that has been observed at several previous apparitions, in particular by Warner (see LCDB references) as part of an on-going project to find spin axes for members of the group. The period given here is consistent with previous results; the data should improve a preliminary spin axis.

6859 Datemasamune

is another Hungaria member that is part of the spin axis project. Finding the period has been difficult because of amplitudes < 0.2 mag. Previous results by Warner are 2006, 12.95 h; 2010, 22.1 h; 2011, 86.1 h.; and 2016b, 5.2879 h. The 2019 data excluded the very long periods and favored one close to the 2016 result. We have adopted the 2019 period of 5.944 h, but other solutions cannot be formally excluded.

The data sets from 2006–2016 were reanalyzed to see if they would support the adopted period given here. The fits in 2006, 2011, and 2016 are very plausible. The 2009 data set was somewhat noisy and so the fit to the new period is not as convincing.

We note that having the ATLAS star catalog with highly-reliable magnitudes played an important role in our 2019 analysis because there was high confidence in zero point matching from night-tonight. In previous years, as can be seen with the wide range of periods, zero point adjustments were much more arbitrary.

9564 Jeffwynn.

The only previously reported period (3.035 h) was by Warner (2013a). Our most recent result is in good agreement.

10480 Jennyblue.

This was a target of opportunity in the field of a Hilda asteroid. Waszczak et al. (2015) found a period of 6.019 h. Forcing the 2019 data to something near that has the maximums only 0.4 rotation phase apart. There’s a good chance of a rotational alias being involved since the two periods differ by almost exactly 0.5 rotations over 24 hours. Given the sparser data set used by Waszczak et al., it’s reasonably safe to adopt our period of 5.356 h as the more likely.

20936 Nemrut Dagi.

There are several previous results in the LCDB for this 5-km Hungaria, e.g. Skiff (2011, 3.293 h) and Warner (2016a, 3.2754 h). Our data set was relatively sparse compared to others, enough that we had to force the period search to a small range covering a range a little larger than the full range of reported periods.

While the 2019 data can be fit to 3.328 h, the solution is hardly conclusive. Regardless, the data will be used to try to improve a preliminary spin axis.

(32772) 1986 JL.

We observed this twice before: Warner (2013c) and Stephens (2016). Those two and our result are in excellent agreement. The seemingly monomodal solution in 2019 is unusual given the amplitude, but not impossible (Harris et al., 2014).

(33324) 1998 QE56.

The latest data set extends our dense lightcurve observations from 2011 to 2019 (see LCDB references). As a result, we hope that, combined with sparse data, a good spin axis model can be developed.

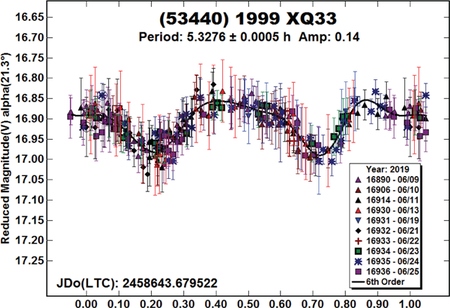

(53440) 1999 XQ33.

This appears to be the first reported rotation period for 1999 XQ33. It is another member of the Hungaria group. It would be required to determine its taxonomic class before calling it a family member.

55854 Stoppani.

Previous results from Skiff (2011) and Warner (2011, 2013b) are all in close agreement with our 2019 analysis. Were it not for the large amplitude overcoming the noisy data on some nights, it may not have been possible to find a period.

(66346) 1999 JU71.

This is a member of the Flora group but it could actually belong to one of the subgroups in the region. The estimated diameter, assuming pV = 0.24, is 2.3 km. There were no previously reported periods in the LCDB to serve as a starting point for analysis. Unfortunately, the data set was too noisy and too sparse to allow finding a definitive solution.

We show two plots phased to two of the possible solutions. Both have gaps in coverage, which might imply a fit by exclusion, which is when the Fourier algorithm finds a local RMS minimum that minimizes the number of overlapping data points. The two periods do not seem to be harmonically related.

(162820) 2001 BK36.

Assuming a default albedo of 0.21 for Eunomia group (or at least region) members gives an estimated diameter of 2.5 km. However, Mainzer et al. (2016) found the asteroid to have an albedo of 0.062. Using H = 15.10, this gave a diameter of 4.8 km.

(302111) 2001 MM3.

We observed this Mars-crosser for three nights in 2019 June. The resulting data was of high quality and almost covered the adopted period of 3.217 h completely each night. That and the large amplitude make the period solution secure. There were no previous period results in the LCDB.

Table II.

Observing circumstances and results. The phase angle is given for the first and last date. If preceded by an asterisk, the phase angle reached an extrema during the period. LPAB and BPAB are the approximate phase angle bisector longitude/latitude at mid-date range (see Harris et al., 1984). Grp is the asteroid family/group (Warner et al., 2009).

| Number | Name | 2019 mm/dd | Phase | LPAB | BPAB | Period(h) | P.E. | Amp | A.E. | Grp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2025 | Nortia | 04/18–04/22 | 17.0,17.1 | 136 | 1 | 5.522 | 0.002 | 0.33 | 0.03 | MB-O |

| 2378 | Pannekoek | 04/22–04/27 | 4.0,5.5 | 205 | 8 | 11.874 | 0.003 | 0.19 | 0.01 | MB-O |

| 2510 | Shandong | 06/08–06/18 | 20.1,23.6 | 223 | 5 | 5.949 | 0.001 | 0.29 | 0.04 | FLOR |

| 2778 | Tangshan | 06/09–06/11 | 17.2,17.8 | 220 | 4 | 3.468 | 0.003 | 0.26 | 0.02 | FLOR |

| 4160 | Sabrina-John | 04/21–04/25 | 25.2,25.5 | 145 | −3 | 5.735 | 0.002 | 0.41 | 0.03 | V |

| 4892 | Chrispollas | 04/21–05/18 | *25.4,28.4 | 167 | −7 | 1584 | 16 | 0.71 | 0.05 | MB-I |

| 5627 | 1991 MA | 04/15–04/18 | *21.7,20.8 | 266 | 16 | 5.365 | 0.002 | 0.48 | 0.03 | H |

| 6310 | Jankonke | 06/08–06/10 | 22.7,23.3 | 224 | 15 | 3.071 | 0.002 | 0.18 | 0.01 | H |

| 6859 | Datemasamune | 06/11–06/28 | 31.4,27.4 | 312 | 20 | 5.944 | 0.001 | 0.12 | 0.01 | H |

| 9564 | Jeffwynn | 05/24–05/25 | 26.2,26.1 | 263 | 32 | 3.03 | 0.003 | 0.11 | 0.02 | MC |

| 10480 | Jennyblue | 04/24–04/26 | 24.3,24.6 | 159 | 3 | 5.356 | 0.003 | 0.92 | 0.03 | FLOR |

| 20936 | Nemrut Dagi | 05/18–05/21 | 23.0,24.1 | 198 | −1 | 3.328 | 0.002 | 0.26 | 0.02 | H |

| 32772 | 1986 JL | 05/14–05/24 | 9.4,12.0 | 228 | 12 | 6.046 | 0.001 | 0.25 | 0.03 | H |

| 33324 | 1998 QE56 | 06/01–06/06 | 24.8,24.7 | 261 | 35 | 6.188 | 0.001 | 0.64 | 0.02 | H |

| 53440 | 1999 XQ33 | 06/09–06/25 | 21.3,23.3 | 248 | 26 | 5.3276 | 0.0005 | 0.34 | 0.04 | H |

| 55854 | Stoppani | 06/11–06/25 | 26.3,28.7 | 214 | 2 | 3.06 | 0.001 | 0.45 | 0.03 | H |

| 66346 | 1999 JU71 | 05/14–05/22 | 4.7,8.4 | 229 | 7 | 5.233 | 0.004 | 0.14 | 0.03 | FLOR |

| 162820 | 2001 BK36 | 03/16–03/17 | 3.4,3.2 | 178 | −5 | 3.95 | 0.01 | 0.33 | 0.03 | EUN |

| 302111 | 2001 MM3 | 06/06–06/08 | 25.5,25.6 | 274 | 31 | 3.217 | 0.001 | 0.38 | 0.03 | MC |

Acknowledgements

Observations at CS3 and continued support of the asteroid lightcurve database (LCDB; Warner et al., 2009) are supported by NASA grant 80NSSC18K0851. Work on the asteroid lightcurve database (LCDB) was also partially funded by National Science Foundation grant AST-1507535. This research was made possible in part based on data from CMC15 Data Access Service at CAB (INTA-CSIC) (http://svo2.cab.inta-csic.es/vocats/cmc15/). This work includes data from the Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System (ATLAS) project. ATLAS is primarily funded to search for near earth asteroids through NASA grants NN12AR55G, 80NSSC18K0284, and 80NSSC18K1575; byproducts of the NEO search include images and catalogs from the survey area. The ATLAS science products have been made possible through the contributions of the University of Hawaii Institute for Astronomy, the Queen’s University Belfast, the Space Telescope Science Institute, and the South African Astronomical Observatory. The purchase of a FLI-1001E CCD cameras was made possible by a 2013 Gene Shoemaker NEO Grants from the Planetary Society.

Contributor Information

Robert D. Stephens, Center for Solar System Studies (CS3)/MoreData!, 11355 Mount Johnson Ct., Rancho Cucamonga, CA 91737 USA

Brian D. Warner, Center for Solar System Studies (CS3)/MoreData! Eaton, CO

References

- Behrend R, (2005, 2018, 2019). Observatoire de Geneve web site, http://obswww.unige.ch/~behrend/page_cou.html

- Hanuš J; Ďurech J; Brož M; Marciniak A; Warner BD; Pilcher F; Stephens R; Behrend R; Carry B; and 111 coauthors (2013). “Asteroids’ physical models from combined dense and sparse photometry and scaling of the YORP effect by the observed obliquity distribution.” Astron. Astrophys 551, A67. [Google Scholar]

- Harris AW; Young JW; Scaltriti F; Zappala V (1984). “Lightcurves and phase relations of the asteroids 82 Alkmene and 444 Gyptis.” Icarus 57, 251–258. [Google Scholar]

- Harris AW; Young JW; Bowell E; Martin LJ; Millis RL; Poutanen M; Scaltriti F; Zappala V; Schober HJ; Debehogne H; Zeigler KW (1989). “Photoelectric Observations of Asteroids 3, 24, 60, 261, and 863.” Icarus 77, 171–186. [Google Scholar]

- Harris AW, Pravec P, Galad A, Skiff BA, Warner BD, Vilagi J, Gajdos S, Carbognani A, Hornoch K, Kusnirak P, Cooney WR, Gross J, Terrell D, Higgins D, Bowell E, Koehn BW (2014). “On the maximum amplitude of harmonics on an asteroid lightcurve.” Icarus 235, 55–59. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins D; Pravec P; Kusnirak Pe.; Hornoch K; Brinsfield J; Allen B; Warner BD (2004). “Asteroid Lightcurve Analysis at Hunters Hill Observatory and Collaborating Stations: November 2007 - March 2008.” Minor Planet Bull. 35, 123–126. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins D; Goncalves RMD (2007). “Asteroid Lightcurve Analysis at Hunters Hill Observatory and Collaborating Stations: June-September 2006.” Minor Planet Bull. 34, 16–18. [Google Scholar]

- Kostov A; Bonev T (2017). “Transformation of Pan-STARRS1 gri to Stetson BVRI magnitudes. Photometry of small bodies observations.” Bulgarian Astron. J 28, 3 (AriXiv:1706.06147v2). [Google Scholar]

- Mainzer AK, Bauer JM, Cutri RM, Grav T, Kramer EA, Masiero JR, Nugent CR, Sonnett SM, Stevenson RA, Wright EL (2016). “NEOWISE Diameters and Albedos V1.0.” NASA Planetary Data System. EAR-A-COMPIL-5-NEOWISEDIAM-V1.0. [Google Scholar]

- Pravec P; Harris AW; Scheirich P; Kušnirák P; Šarounová L; Hergenrother CW; Mottola S; Hicks MD; Masi G; Krugly Yu.N.; Shevchenko VG; Nolan MC; Howell ES; Kaasalainen M; Galád A; Brown P; Degraff DR; Lambert JV; Cooney WR; Foglia S (2005). “Tumbling asteroids.” Icarus 173, 108–131. [Google Scholar]

- Pravec P; Scheirich P; Durech J; Pollock J; Kusnirak P; Hornoch K; Galad A; Vokrouhlicky D; Harris AW; Jehin E; Manfroid J; Opitom C; Gillon M; Colas F; Oey J; Vrastil J; Reichart D; Ivarsen K; Haislip J; LaCluyze A (2014). “The tumbling state of (99942) Apophis.” Icarus 233, 48–60. [Google Scholar]

- Skiff BA (2011). Posting on CALL web site. http://www.minorplanet.info/call.html

- Stephens RD (2016). “Asteroids Observed from CS3: 2016 January-March.” Minor Planet Bull. 43, 252–255. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens RD (2017). “Asteroids Observed from CS3: 2016 October – December.” Minor Planet Bull. 44, 120–122. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonry JL; Denneau L; Flewelling H; Heinze AN; Onken CA; Smartt SJ; Stalder B; Weiland HJ; Wolf C (2018). “The ATLAS All-Sky Stellar Reference Catalog.” Astrophys. J 867, A105. [Google Scholar]

- Warner BD (2004). “Lightcurve analysis for numbered asteroids 1351, 1589, 2778, 5076, 5892, and 6386.” Minor Planet Bull. 31, 36–39. [Google Scholar]

- Warner BD (2006). “Asteroid lightcurve analysis at the Palmer Divide Observatory - February - March 2006.” Minor Planet Bull. 33, 82–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner BD (2010). Asteroid Lightcurve Analysis at the Palmer Divide Observatory: 2009 June-September.” Minor Planet Bull. 37, 24–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner BD (2011). “Asteroid Lightcurve Analysis at the Palmer Divide Observatory: 2011 March - July.” Minor Planet Bull. 38, 190–195. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner BD (2013a). “Asteroid Lightcurve Analysis at the Palmer Divide Observatory: 2012 June – September.” Minor Planet Bull. 40, 26–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner BD (2013b). “Asteroid Lightcurve Analysis at the Palmer Divide Observatory: 2012 September - 2013 January.” Minor Planet Bull. 40, 71–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner BD (2013c). “Asteroid Lightcurve Analysis at the Palmer Divide Observatory: 2013 January – March.” Minor Planet Bull. 40, 137–145. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner BD (2016a). “Asteroid Lightcurve Analysis at CS3-Palmer Divide Station: 2015 October-December.” Minor Planet Bull. 43, 137–140. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner BD (2016b). “Asteroid Lightcurve Analysis at CS3-Palmer Divide Station: 2015 December - 2016 April.” Minor Planet Bull. 43, 227–233. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner BD; Harris AW; Pravec P (2009). “The Asteroid Lightcurve Database.” Icarus 202, 134–146. Updated 2019 Feb. http://www.minorplanet.info/lightcurvedatabase.html [Google Scholar]

- Waszczak A; Chang C-K; Ofek EO; Laher R; Masci F; Levitan D; Surace J; Cheng Y-C; Ip W-H; Kinoshita D; Helou G; Prince TA; Kulkarni S (2015). “Asteroid Light Curves from the Palomar Transient Factory Survey: Rotation Periods and Phase Functions from Sparse Photometry.” Astron. J 150, A75. [Google Scholar]

- Zeigler K; Banshaw B; Gass J (2017). “Photometric Observations of Asteroid 4742 Caliumi, 5267 Zegmott (18429) 1994 AO1, (26421) 1999 XP113, and (27675) 1981 CH.” Minor Planet Bull. 44, 259–260. [Google Scholar]