The novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has imposed a severe strain on healthcare systems worldwide and is now affecting all hospitals in the United States.1 As of this writing in early April 2020, most large medical centers in the United States have either restricted or completely cancelled elective surgical procedures, including cardiovascular procedures. A recent survey of vascular surgery practices around the world found that most have significantly scaled back elective surgery in the face of the pandemic.2 We have addressed these challenges by modifying our surgical indications and work flow to accommodate the constraints of this new environment while continuing to provide appropriate and timely surgical care for patients with aortic disease. In the present report, we describe the modifications we have implemented in clinical care provided by the multidisciplinary aortic disease program at our large regional referral institution to address the challenges presented by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Clinical repercussions of COVID-19

Numerous reports have documented the deleterious effects of COVID-19 on the myocardium, possibly related to the significant inflammatory response generated by the viral infection.3, 4, 5, 6 Data on the implications of this phenomenon in aortic disease are lacking. Aortic inflammation has been shown to play a role in aneurysm progression7; thus, it is theoretically possible that COVID-19 could worsen aortic disease or cause increased aortic complications. More data are needed to evaluate this question as patients with concomitant COVID-19 and aortic disease are identified and monitored. However, given the rapid escalation of this worldwide pandemic, we do not have the luxury of waiting for definitive data regarding the effects of COVID-19 on the cardiovascular system—we must proceed in the face of this uncertainty to continue to care for our patients.8

National and international guidelines on the timing of cardiovascular procedures

Multiple professional societies have issued guidance for cardiovascular and surgical specialists in the face of this crisis. The American College of Cardiology has recommended that all elective cardiac catheterization procedures be postponed and has modified the recommendations for emergency situations such as myocardial infarction.9 The Chinese Cardiovascular Society issued guidelines recommending that control of the epidemic was the highest priority, even in the face of the acute presentation of patients with cardiovascular disease.10 The American College of Surgeons issued guidelines for elective surgery, with the recommendation that surgery for patients with an aortic aneurysm but without complications could be postponed.11 The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services published a guidance document on March 19, 2020 detailing a 3-tiered priority framework for the postponement of elective surgical procedures.12 Our hospital's operating room executive committee directed all surgical services to cancel elective procedures for patients with upper respiratory symptoms effective on March 12, 2020. This guidance was expanded to mandate rescheduling of all elective procedures starting on March 16, 2020.

Local approach to surgical criteria and operative intervention

Although these broad government and hospital system guidelines have been helpful to provide context for the discussion, the faculty of the aortic disease program sought to develop a more specific approach for our patients. As such, we have implemented modifications to our surgical criteria for patients who would otherwise meet the indications for operative intervention. This decision has been informed by both our internal discussions and the Society for Vascular Surgery guidelines (Table ).13 Surgery for most patients with isolated descending thoracic or abdominal aortic aneurysms <6.5 cm and patients with root, ascending, or arch aneurysms <6.0 cm has been postponed until the surge has passed, which we anticipate will be in 2 to 3 months. Patients with both proximal aortic aneurysms (root, ascending, or arch aneurysms) and coronary artery disease or valve disease are considered on a case-by-case basis. Symptomatic aortic stenosis with concomitant aortic aneurysm has been classified as time-sensitive, and we have proceeded with these procedures. Surgery for patients with subacute or chronic type B aortic dissections who otherwise have met our criteria for thoracic endovascular aortic repair has similarly been delayed until after the surge has passed. The locoregional effects of COVID-19 should be considered as each hospital system and aortic surgery practice develops an individualized approach to prioritization of scheduling. Clearly, hospitals with a greater number of patients with COVID-19 will likely be forced to impose stricter restrictions on elective surgical scheduling.

Table.

Society for Vascular Surgery recommendations for tiered approach to elective vascular surgical procedure scheduling

| Category | Condition | Tier class |

|---|---|---|

| AAA | Ruptured or symptomatic TAAA or AAA | 3 Do not postpone |

| Aneurysm associated w/infection or prosthetic graft infection | 3 Do not postpone | |

| AAA >6.5 cm | 2b Postpone if possible | |

| TAAA >6.5 cm | 2b Postpone if possible | |

| AAA <6.5 cm | 1 Postpone | |

| Aneurysm peripheral | Peripheral aneurysm, symptomatic | 3 Do not postpone |

| Peripheral aneurysm, asymptomatic | 2a Consider postponing | |

| Pseudoaneurysm repair: Not candidate for thrombin injection or compression, rapidly expanding, complex | 3 Do not postpone | |

| Symptomatic non-aortic intra-abdominal aneurysm | 3 Do not postpone | |

| Asymptomatic non-aortic intra-abdominal aneurysm | 2a Consider postponing | |

| Aortic dissection | Acute aortic dissection with rupture or malperfusion | 3 Do not postpone |

| Aortic emergency NOS | AEF with septic/hemorrhagic shock, or signs of impending rupture | 3 Do not postpone |

AAA, Abdominal aortic aneurysm; AEF, aortoesophageal; NOS, not otherwise specified; TAAA, thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm.

Reproduced, with permission, from Society for Vascular Surgery.13

Extent of operation and surgical approach

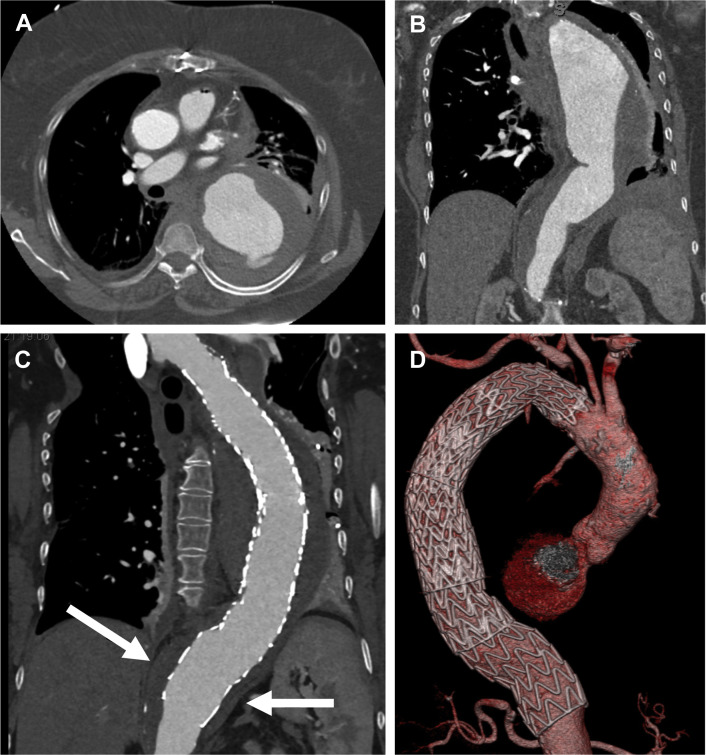

We have also considered altering our operative plan for patients with aortic disease in need of high-risk operations to consider the current and projected constrained resources of our hospital system resulting from the pandemic. Should patients be temporized with an expeditious strategy of stabilization through endovascular repair rather than a definitive open repair to decrease the length of stay and preserve scarce hospital resources? Should an anticipated need for personal protective equipment (PPE), blood products, or prolonged intubation or intensive care unit (ICU) stay in this time of constraint play a role in decision making? We recently treated a patient who had presented with a ruptured thoracoabdominal aneurysm using a temporizing thoracic endovascular aortic repair procedure rather than performing a more definitive, but more resource-intensive, open repair. Although we were able to achieve an adequate proximal seal in zone 2 of the arch, we accepted a suboptimal distal landing zone within the aneurysm thrombus in the supraceliac aorta (Fig 1 ). This approach stabilized the patient and reduced the usage of hospital resources. She was expeditiously discharged, and we will perform the definitive repair once the surge of COVID-19 cases has abated.

Fig 1.

Images of a 68-year-old woman with acute aortic syndrome, ruptured thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm. Admission computed tomography angiograms: axial (A) and coronal (B) reconstructions. C, Coronal computed tomography angiogram reconstruction after emergency thoracic endovascular aortic repair demonstrating the suboptimal distal landing zone (arrows; endograft in aneurysm thrombus). D, Three-dimensional reconstruction demonstrating patent left common carotid to left subclavian bypass graft and a good proximal seal in zone 2.

Personal protective measures in the management of COVID-19 patients with aortic disease

A limited report from Wuhan, China, documented successful surgical treatment of 4 patients with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 who had presented with type A aortic dissection.14 The investigators stressed the importance of N95 mask protection and the multiple layers of gloves and gowns worn by the anesthesia team. These layers of PPE were disinfected in between the preprocedural steps of intubation and central catheter insertion. They also used video laryngoscopy to allow the anesthesia providers to maintain the maximum distance between themselves and the patient's oropharynx. Muscle relaxants and high-dose narcotics were administered before airway manipulation to minimize the risk of the patient coughing and vomiting, which would have aerosolized secretions and greatly increased the risk of virus transmission. They used tape to secure all seams in the PPE, including between the gloves and gown and between the mask and goggles. These increased universal precautions should be used by all anesthesia teams providing airway management for patients requiring surgery who have known or suspected COVID-19. It is unclear whether this level of protection is necessary for the surgical team performing aortic surgery (after the airway manipulation portion of the procedure has been completed). However, increased precautions might be prudent for all members of the care team.

Patient decision making

Although the burden of cancelling or postponing elective aortic surgery falls primarily on surgeons, patients are also struggling with these difficult decisions. At least three patients who had met our criteria for elective aneurysm repair have decided, after appropriate shared medical decision-making efforts, to postpone their surgery until they either become symptomatic or the surge has passed. All three patients require endovascular repair of an abdominal aneurysm, two of which are juxtarenal. However, these patients are >60 years old and have underlying medical comorbidities. They have elected to assume the risk of an aortic complication to avoid the risk of contracting COVID-19. Additionally, our hospital has implemented strict no-visitor policies in an effort to reinforce social distancing and decrease the spread of the virus. This has not factored significantly into physician decision making but has been a critical component of patient decision making.

Role of telemedicine

Increased use of telemedicine visits can reduce the exposure of patients to hospitals and clinics actively treating patients with COVID-19. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services recently waived the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act compliance regulations for multiple video and voice platforms and allowed for provider and health system reimbursement for telemedicine visits, greatly facilitating the expansion of these processes.15 Telemedicine is an ideal adjunct for the clinical management of aortic disease, because these patients rarely have critical clinical decisions that rely on physical examinations, which must be performed in person. We have transitioned most of our initial patient evaluations and routine surveillance clinic visits to the telemedicine platform. Routine postoperative visits are still performed in person on a case-by-case basis, depending on the specific needs of each patient. Both patients and providers have appreciated this approach to minimize potential virus exposure but maintain high-quality clinical care. The use of telemedicine might be one of the lasting effects of the pandemic on clinical practice, especially for patients who live far from a tertiary care center. Routine postoperative follow-up examinations or routine surveillance imaging studies can, and were already, often obtained locally. However, these patients then must drive 2 to 6 hours to be seen in person. Now that both patients and providers have experienced that in-person visits are not always necessary, the likelihood of returning to the former practice model is low.

Management of pending surgical backlog and hospital capacity

The treatment of patients whose elective surgery was postponed during the crisis will be an important consideration in the months after the peak surge in COVID-19 hospital resource usage. The backlog of procedures will cause a significant strain on operating room, intensive care, and hospital capacity that could result in further delays in surgical care. In addition, patients requiring aortic surgery require a relatively high usage of postacute care in skilled nursing facilities and inpatient rehabilitation centers.16 These resources will likely be stressed by the coming influx of patients recovering from COVID-19, creating an impediment to the discharge of patients after aortic surgery and further reducing hospital capacity.17

The most prudent course of action will be institution and hospital system specific. However, all surgical practices will benefit from pursuing a deliberate approach to the period of post-COVID return to normalcy that we all hope to achieve. A recent report from an acute care surgical program described a practical prioritization framework for addressing this challenge.18 In our program, we have instituted a tiered prioritization model for all cardiovascular surgical patients, including patients with aortic disease. As new patients are referred or existing patients meet the criteria for surgery, they are assigned a priority from 1 to 3 according to the urgency and a master list is compiled. Given that our operating room block time is structured by service, the cardiac and vascular services have separate master lists. Our entire faculty meet (virtually) once each week to evaluate the list and agree on the prioritization of each patient in a rolling fashion to allow us to remain responsive to the changing hospital resource environment.

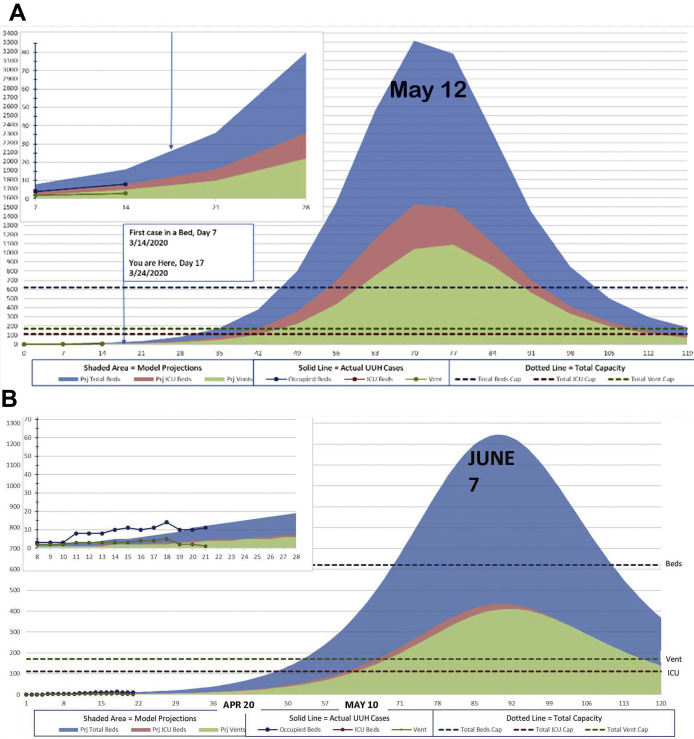

Although the priority of disease is the most important factor in determining each patient's position in the queue, we also consider the projected length of stay in the ICU and in the hospital for each patient after surgery. We are fortunate to have a large dedicated cardiovascular ICU; however, the ICU service is limited by the number of beds and staff available. To prevent complete saturation of the ICU service (and the resultant inability to perform elective surgery), we have planned to alternate scheduling of patients with projected longer ICU stays with patients expected to recover more quickly. This approach will preserve the ICU throughput and allow for the most efficient clearance of our patient backlog. The decision-making model will differ for each regional and institutional environment. However, multidisciplinary collaboration with social workers, the blood bank, supply chain, and hospital staffing will be critical. Efforts to “flatten the curve” have already shown effects (Fig 2 ). The intended consequence of these mitigation efforts is that the increase in patients with COVID-19 will have a prolonged but lower peak. If this strategy is successful, many regions will continue to experience resource limitations, not just in the short term, but also for many months. An understanding of the local modeling of the disease burden and system resources will be critical as we continue to evaluate and re-evaluate our patients who are currently in limbo regarding their treatment. Success in flattening the curve will also mean that the devastating choices faced by clinicians in areas where this did not occur can be avoided. At present, we do not anticipate the need to palliate patients who would otherwise be treated because of a lack of beds, ventilators, or PPE. We are still in the “pre-peak” part of our curve, and this decision will be assessed by the aortic program faculty as necessary. We have no algorithm per se because the data are changing constantly. However, the vascular surgery activity condition or VASCCON model reported by Forbes19 can be implemented with an understanding of local conditions. At present, we receive a daily report and a live dashboard is available with important institutional data, including the number of patients with COVID-19, patients under investigation, PPE supply chain, ventilator and ICU bed status, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation capacity. This type of transparency will be critical for any institution considering loosening or restricting current surgical care.

Fig 2.

Projected coronavirus disease 2019 case burden for the University of Utah Health system. A, The initial analysis projected a surge in cases in mid-May. B, However, the revised “flattened” projection (released March 31, 2020) anticipates a surge in cases in early June.

Effects on surgical training

As a teaching hospital, all our training programs have been significantly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Both our vascular and thoracic surgical fellows have been maintaining a clinical presence in the hospital for patient care and treating patients as usual. With the drastic reduction in elective case volume, our fellows have also experienced a decrease in their case volumes. Although we are fortunate that we are a high-volume center and our graduating fellows have already met the case requirements for graduation, we have been emphasizing the importance of simulation laboratory practice time and have maintained open communication between the faculty and fellows to maximize learning with each opportunity for a surgical case. We have cancelled all in-person meetings and didactic sessions, including education and morbidity and mortality conferences, which have all been moved to a video conferencing format. Given the sophistication of the software available, we have not experienced a drop off in conference participation or quality with this change. We have also begun discussions among the faculty to consider keeping the virtual format indefinitely for some select conferences and education activities, because it can facilitate participation for fellows spread across multiple different hospitals rather than requiring in-person attendance.

Conclusions

These are uncertain times, and a balanced thoughtful approach is needed for the treatment of patients with aortic disease. It is crucial that the international community of aortic specialists work together to achieve consensus on how best to prioritize appropriate patient care and preserve the capacity of the healthcare system to address this crisis. The Society for Vascular Surgery is to be commended for developing clear guidelines surrounding this type of decision making. Ideally, all relevant societies will draft such guidelines in a collaborative consensus-building manner, both to minimize differences in regional decision making and to provide a “pandemic standard of care” to protect physicians across specialties from medicolegal liability for outcomes related to resource-constrained decision making. Government intervention could also have a role. New York State has recently passed legislation allowing for legal protection for physicians and hospital systems making difficult decisions in the face of the pandemic. Given the high morbidity and mortality for untreated acute aortic syndrome, it seems clear that surgical treatment should be offered whenever possible to these patients. Decision making for elective or urgent aortic surgery is much more nuanced and will be best served by an institution- and program-specific approach. By taking these collective measures, we as a specialty can continue to provide the best possible care for our patients in the context of our new shared reality.

Footnotes

Author conflict of interest: none.

The editors and reviewers of this article have no relevant financial relationships to disclose per the JVS policy that requires reviewers to decline review of any manuscript for which they may have a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Adams J.G., Walls R.M. Supporting the health care workforce during the COVID-19 global epidemic. JAMA. 2020;323:1439–1440. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ng J.J., Ho P., Dharmaraj R.B., Wong J.C.L., Choong A.M.T.L. The global impact of COVID-19 on vascular surgical services. J Vasc Surg. 2020;71:2182–2183.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2020.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Madjid M., Safavi-Naeini P., Solomon S.D., Vardeny O. Potential effects of coronaviruses on the cardiovascular system: a review. JAMA Cardiol. 2020 Mar 27 doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1286. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clerkin K.J., Fried J.A., Raikhelkar J., Sayer G., Griffin J.M., Masoumi A. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2020;141:1648–1655. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.046941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shi S., Qin M., Shen B., Cai Y., Liu T., Yang F. Association of cardiac injury with mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol. 2020 Mar 25 doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0950. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guo T., Fan Y., Chen M., Wu X., Zhang L., He T. Cardiovascular implications of fatal outcomes of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA Cardiol. 2020 Mar 27 doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1017. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MA3RS Investigators Aortic wall inflammation predicts abdominal aortic aneurysm expansion, rupture, and need for surgical repair. Circulation. 2017;136:787–797. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.028433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Driggin E., Madhavan M.V., Bikdeli B., Chuich T., Laracy J., Bondi-Zoccai G. Cardiovascular considerations for patients, health care workers, and health systems during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2352–2371. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Welt F.G.P., Shah P.B., Aronow H.D., Bortnick A.E., Henry T.D., Sherwood M.W. Catheterization laboratory considerations during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic: from ACC's interventional council and SCAI. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2372–2375. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Han Y., Zeng H., Jiang H., Yang Y., Yuan Z., Cheng X. CSC expert consensus on principles of clinical management of patients with severe emergent cardiovascular diseases during the COVID-19 epidemic. Circulation. 2020;141:e810–e816. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American College of Surgeons COVID-19: Elective Case Triage Guidelines for Surgical Care. https://www.facs.org/covid-19/clinical-guidance/elective-case Available at:

- 12.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services CMS Adult Elective Surgery and Procedures Recommendations. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/31820-cms-adult-elective-surgery-and-procedures-recommendations.pdf Available at:

- 13.Society for Vascular Surgery COVID-19 Guidelines and Resources. https://vascular.org/news-advocacy/covid-19-resources#Guidelines&Tools Available at:

- 14.He H., Zhao S., Han L., Wang Q., Xia H., Huang X. Anesthetic management of patients undergoing aortic dissection repair with suspected severe acute respiratory syndrome COVID-19 infection. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2020;34:1402–1405. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2020.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Medicare Telemedicine Health Care Provider Fact Sheet. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/medicare-telemedicine-health-care-provider-fact-sheet Available at:

- 16.Balentine C.J., Mason M.C., Richardson P.J., Kougias P., Bakaeen F., Naik A.D. Variation in postacute care utilization after complex surgery. J Surg Res. 2018;230:61–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2018.04.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grabowski D.C., Joynt Maddox K.E. Postacute care preparedness for COVID-19: thinking ahead. JAMA. 2020 Mar 25 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4686. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ross S.W., Lauer C.W., Miles W.S., Green J.M., Christmas A.B., May A.K. Maximizing the calm before the storm: tiered surgical response plan for novel coronavirus (COVID-19) J Am Coll Surg. 2020;230:1080–1091.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Forbes T.L. Vascular surgery activity condition is a common language for uncommon times. J Vasc Surg. 2020;72:391–392. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2020.04.490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]