Graphical abstract

Abbreviations: LS, Liu Shen capsule; TCM, traditional Chinese medicine; SARS-CoV, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus; MERS-CoV, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; IL-1β, interleukin-1beta; IL-6, interleukin-6; IL-8, interleukin-8; CCL-2/MCP-1, monocyte chemoattracctant protein-1; CXCL-10/IP-10, interferon-inducible protein-10; VERO, E6 cells monkey kidney cell line; G-CSF, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; MIP1a, recombinant macrophage inflammatory protein 1 alpha; TC50, 50 % toxicity concentration; EC50, 50 % effective concentration; MTT, methyl thiazolyl tetrazolium; TCID50, 100 × 50 % tissue culture infective dose; FBS, foetal bovine serum; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; HPLC, high-performance liquid chromatography; CPE, cytopathic effect; RT-PCR, real-time polymerase chain reaction; COVID-19, 2019 coronavirus disease; MOI, multiplicity of infection; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide

Keywords: Liu Shen capsule, SARS-CoV-2, Antiviral, Anti-inflammatory

Abstract

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has spread worldwide through person-to-person contact, causing a public health emergency of international concern. At present, there is no specific antiviral treatment recommended for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Liu Shen capsule (LS), a traditional Chinese medicine, has been proven to have a wide spectrum of pharmacological properties, such as anti-inflammatory, antiviral and immunomodulatory activities. However, little is known about the antiviral effect of LS against SARS-CoV-2. Herein, the study was designed to investigate the antiviral activity of SARS-CoV-2 and its potential effect in regulating the host’s immune response. The inhibitory effect of LS against SARS-CoV-2 replication in Vero E6 cells was evaluated by using the cytopathic effect (CPE) and plaque reduction assay. The number of virions of SARS-CoV-2 was observed under transmission electron microscope after treatment with LS. Proinflammatory cytokine expression levels upon SARS-CoV-2 infection in Huh-7 cells were measured by real-time quantitative PCR assays. The results showed that LS could significantly inhibit SARS-CoV-2 replication in Vero E6 cells, and reduce the number of virus particles and it could markedly reduce pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, IL-8, CCL-2/MCP-1 and CXCL-10/IP-10) production at the mRNA levels. Moreover, the expression of the key proteins in the NF-κB/MAPK signaling pathway was detected by western blot and it was found that LS could inhibit the expression of p-NF-κB p65, p-IκBα and p-p38 MAPK, while increasing the expression of IκBα. These findings indicate that LS could inhibit SARS-CoV-2 virus infection via downregulating the expression of inflammatory cytokines induced virus and regulating the activity of NF-κB/MAPK signaling pathway in vitro, making its promising candidate treatment for controlling COVID-19 disease.

1. Introduction

Coronaviruses (CoVs) are a group of enveloped viruses named for their coronary appearance with positive single-stranded RNA genomes that infect animal hosts [1]. Many of the coronaviruses were recognized as viruses typically causing pneumonia and colds until the emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) in 2002 and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in 2012 from zoonotic sources [2]. In addition, a novel coronavirus, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), causing severe acute respiratory disease emerged recently in Wuhan, China in December 2019 [3,4]. Like the other two highly pathogenic coronaviruses SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2 can also cause severe respiratory illness and even death. Moreover, the population's susceptibility to these highly pathogenic coronaviruses has contributed to large outbreaks and evolved into the public health events, highlighting the necessity to prepare for the future emerging viruses [5].

Similar to SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2 spreads rapidly among humans and likely originates in bats [3,6]. The initial patient cluster with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection was reported as pneumonia with unknown aetiology, which bore some resemblance to both SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV infections and was associated with ICU admission and high mortality. Moreover, patients requiring ICU admission had higher concentrations of G-CSF, IP-10, MCP-1, MIP-1A, and TNF-α than did those not requiring ICU admission, suggesting that the cytokine storm was associated with disease severity [7]. To date the severity of SARS-CoV-2 has tended to be mild, the risk of fatality among hospitalized cases was 4.3 % in a single-center case series of 138 hospitalized patients [8], and the infection fatality risk could be below 1% or even below 0.1 % in a large number of undetected relatively mild infections [9]. However, the basic reproduction number (R0) of person-to-person spread was about 2.6, which meant that the cases of infection would grow at an exponential rate. As of 7 February, 2020, 57,620 cases of SARS-CoV-2 have been reported in China, including 26,359 suspected cases, and a sustained increase is predicted. It is challenging to judge the severity and predict the consequences of the information available to date. Since no specific antiviral treatment for SARS-CoV-2 infection is currently available, supportive cares, including symptomatic controls and prevention of complications remain the most important management strategy, especially in preventing acute respiratory distress syndrome [4,10]. Currently, there is no special antiviral treatment or vaccine against the new virus. Therefore, it is of great importance to research and develop effective and safe antiviral drugs.

It has been reported that many traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) prescriptions could not only inhibit the replication of virus directly, but also attenuate excessive pro-inflammatory responses and tissue damage by viruses [[11], [12], [13]]. Therefore, it is significantly to study the traditional Chinese medicines that have obvious advantages in the treatment of the new virus. Liu Shen capsule (LS), a traditional Chinese medicine, has been used to treat influenza, tonsillitis, pharyngitis, and mumps for more than a century [14]. It consists of Bezoar (the gall-stone of Bos taurus domesticus Gmelin), Musk (the excretion of Moschus), cinobufagin venom toad (the excretion of Venenum Bufonis), pearl (the shell of Pernulo), realgar, and borneol. In previous studies, it was shown that the LS exhibited a wide spectrum of pharmacological properties, such as anti-inflammatory, anticancer, antiviral, analgesic, antibacterial, and immunomodulatory activities [15,16]. In addition, LS could inhibit viral propagation and regulate immune function and achieved similar therapeutic effectiveness with oseltamivir in reducing the course of H1N1 virus infection. Notably, the anti-influenza activity of LS in infected mice might depend on the regulation of cytokines, particularly in cytokine storm associated cytokines, such as IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α [17]. However, there is no exact evidence that LS is effective in the treatment of SARS-CoV-2 and its mechanisms of action remain obscure. Therefore, to study the antiviral activity of LS on SARS-CoV-2 and its potential effect in regulating the host’s immune response, we evaluated the antiviral and anti-inflammatory efficiency of LS against a clinical isolate of SARS-CoV-2 from Guangzhou in vitro.

In this study, a comprehensive evaluation of the antiviral and anti-inflammatory activity of LS was performed in vitro with SARS-CoV-2 infection. It demonstrated that LS inhibited the replication of the virus in a dose-dependent manner and found that LS could reduce the number of viral particles. Moreover, LS could markedly decrease pro-inflammatory cytokine expression in infected human hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines (Huh-7), which may result in gaining a comprehensive understanding of the inhibition of LS against SARS-CoV-2 infection.

2. Methods

2.1. Reagents

LS (lot: SA01004C) used in this study was produced and provided by Leiyunshang Pharmaceutical Group Co., Ltd. (Suzhou, China). The LS was triturated, 50 mg was prepared in 10 mL dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). The mixture was ultrasonicated for 4 h and then centrifuged at 4000 g for 15 min. The supernatant was filtered through a 0.22 μm syringe filter before use. In the previous study, the index components in LS were detected by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). HPLC revealed that LS contained 0.12 % gamabufotalin, 0.10 % arenobufagin, 0.26 % telocinobufagin, 0.21 % desacetylcinobufotalin, 0.25 % bufotalin, 0.41 % cinobufotalin, 0.27 % bufalin, 0.70 % resibufogenin, 0.68 % cinobufagin, 1.81 % cholic acid, 0.27 % anserine deoxycholic acid, and 0.23 % deoxycholic acid [18]. Remdesivir was kindly provided by Prof. Jiancun Zhang from Guangzhou Institutes of Biomedicine and Health, Chinese Academy of Sciences and was dissolved in DMSO to 100 μg/mL and stored at −20 °C before using. IκBα rabbit monoclonal (lot: 4812), p-IκBα rabbit monoclonal (lot: 2859), NF-κB p65 rabbit monoclonal (lot: 8242), p-NF-κB p65 rabbit monoclonal (lot:3033), p38 MAPK rabbit monoclonal (lot: 8690) and p-p38 MAPK rabbit monoclonal (lot: 4631) antibodies were provided by Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA, USA).

2.2. Cell lines and the virus

The African green monkey kidney epithelial (Vero E6) cells and human hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines (Huh-7) were purchased from ATCC. The cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Gibco, USA) with 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. SARS-CoV-2 (Genebank accession no. MT123290.1) was clinical isolates from the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University. The virus was propagated and adapted as previously described [19]. The 50 % tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) of the virus was determined using the Reed Muench method (TCID50 = 10-6/100 μL). Virus stocks were collected and stored at −80 °C. All the infection experiments were performed in a biosafety level-3 (BLS-3) laboratory.

2.3. Cytotoxicity assay

The cytotoxic effects of LS or Remdesivir on Vero E6 and Huh-7 cells were evaluated by MTT assay [20]. Briefly, Vero E6 (5 × 104 cells/well) and Huh-7 (5 × 104 cells/well) cells grown in a monolayer in 96-well plates were rinsed with PBS followed by incubation with indicated concentrations of LS. After 72 h, the cells were stained with MTT solution at 0.5 mg/mL for 4 h. The supernatants were then removed, and the formed formazan crystals were dissolved in 200 μL dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). The absorbance at 570 nm was determined using a Multiskan Spectrum reader (Thermo Fisher, USA).

2.4. Cytopathic effect (CPE) inhibition assay

To investigate the antiviral effects of LS against SARS-CoV-2, the CPE inhibition assay under the nontoxic concentration of LS was employed. Briefly, the Vero E6 cell monolayers were grown in 96-well plates and inoculated with 100 TCID50 of coronavirus strains at 37 °C for 2 h. The inoculum was removed, and the cells were subsequently incubated with indicated concentrations of LS and the positive control Remdesivir. Following 72 h of incubation, the infected cells showed 100 % CPE under the microscope. The percentage of CPE in LS-treated cells was recorded. The 50 % inhibition concentration (IC50) of the virus-induced CPE by LS was calculated as described and the selectivity index (SI) was determined from the CC50 to EC50 ratio [21].

2.5. Plaque reduction assay

The plaque reduction assay was performed as previously described [21]. Briefly, Vero E6 cells monolayers in 6-well plates were rinsed with PBS and incubated with 100 plaque-forming unit (PFU) of SARS-CoV-2. Following 2 h of incubation, the inoculum was removed, and the cells were covered with agar/basic medium mixture, which contained 0.8 % agar and indicated concentrations of LS or Remdesivir. The plates were then incubated at 37 ℃ for 48 h, followed by fixation in 4 % formalin for 30 min. The overlays were then removed and stained with 0.1 % crystal violet for 3 min. The plaques were visualized and counted. The IC50 of the virus-induced plaques by LS was calculated as described [21].

2.6. RNA isolation and reverse transcriptase-quantitative PCR analysis (RT-qPCR)

To further identify the possible underlying mechanisms of LS, we used several drug concentrations, with high antiviral efficiency for subsequent experiments. The primers of TNF-α, IL-6, CCL-2/MCP-1, IL-1β, IL-8, CXCL-10/IP-10 and GAPDH genes (Table 1 ) were designed by using Primer 5.0.

Table 1.

Primer sequence for RT-qPCR.

| Target Gene | Direction | Sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|

| IL-1β | Forward | GCACGATGCACCTGTACGAT |

| Reverse | AGACATCACCAAGCTTTTTTGCT | |

| Probe | FAM-ACTGAACTGCACGCTCCGGGACTC-TAM | |

| TNF-α | Forward | AACATCCAACCTTCCCAAACG |

| Reverse | GACCCTAAGCCCCCAATTCTC | |

| Probe | FAM-CCCCCTCCTTCAGACACCCTCAACC-TAM | |

| IL-6 | Forward | CGGGAACGAAAGAGAAGCTCTA |

| Reverse | CGCTTGTGGAGAAGGAGTTCA | |

| Probe | FAM-TCCCCTCCAGGAGCCCAGCT-TAM | |

| MCP-1 | Forward | CAAGCAGAAGTGGGTTCAGGAT |

| Reverse | AGTGAGTGTTCAAGTCTTCGGAGTT | |

| Probe | FAM-CATGGACCACCTGGACAAGCAAACC-TAM | |

| IP-10 | Forward | GAAATTATTCCTGCAAGCCAATTT |

| Reverse | TCACCCTTCTTTTTCAT-TGTAGCA | |

| Probe | FAM-TCCACGTGTTGAGATCA-TAM | |

| IL-8 | Forward | CTTGGTTTCTCCTTTATTTCTA |

| Reverse | GCACAAATATTTGATGCTTAA | |

| Probe | FAM-TTAGCCACCATCTTACCTCACAGT-TAM | |

| GAPDH | Forward | GAAGGTGAAGGTCGGAGTC |

| Reverse | GAAGATGGTGATGGGATTTC | |

| Probe | FAM-CAAGCTTCCCGTTCTCAGCC-TAM |

Briefly, Huh-7 cell monolayer in 12-well plates were rinsed with PBS and then exposed to coronavirus at the multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1 for 2 h. The inoculums were removed after infection, and the cells were divided into six groups: normal control group (NC), virus-infected group (virus), Remdesivir and three concentrations of LS. The cells were harvested at 48 h. Total RNA from the different groups was extracted according to the specification of the RNA reagent (Invitrogen, MA, USA), and reverse transcription of RNAs was quantified by using the PrimeScript™ RT Master Mix Kit (Takara Bio, Japan). Then, RT-PCR was performed on cDNA samples via the SYBR Premix Ex Tap™ II (Takara Bio, Japan). The PCR data were analysed using the detection system (ABI PRISM® 7500 Real-time PCR system, Applied Biosystems Co., USA). The relative amount of PCR products was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method as previously described [22].

2.7. Transmission electron microscope (TEM) observation of the surface of infected cells

Confluent monolayer culture of Vero E6 cells prepared in 6-well plates was inoculated with the virus and incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. At 2 h p.i., the culture was washed twice with DMEM to remove free viruses and incubated at 37 °C with or without 1 μg LS and Remdesivir. After 24 h, the cells were fixed with 2.5 % glutaraldehyde in 0.15 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) and post-fixed with 1% osmium tetroxide. The fixed cells were dehydrated through a series of ethanol and butanol mixtures [23], and observed under the JSM-6340 SEM (JEOL, Japan).

2.8. Western blot assay

The total proteins of the samples were extracted from the cells with radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (DGCS Biotechnology, China). The protein concentrations of the samples were detected by using the BCA kit (Beyotime, China). Then, 20 mg of the cell extract was separated by 8% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and then they were transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, USA). The membranes were blocked with 5% BSA and incubated with different primary antibodies over night at 4 °C. And then, the membranes with different primary antibodies were incubated with different secondary antibodies for 1 h. The immune complexes were immunoblotted and the immunodetection was performed by using the enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (Fdbio, China).

2.9. Data analysis

All data in this study were analysed by using analysis of variance (ANOVA) with SPSS ver. 19.0 (Armonk, NY, USA). Data were presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Differences in multiple groups were determined by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s honest significant difference (HSD) test. A P-value<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Result

3.1. Antiviral activity of LS on SARS-CoV-2 in vitro

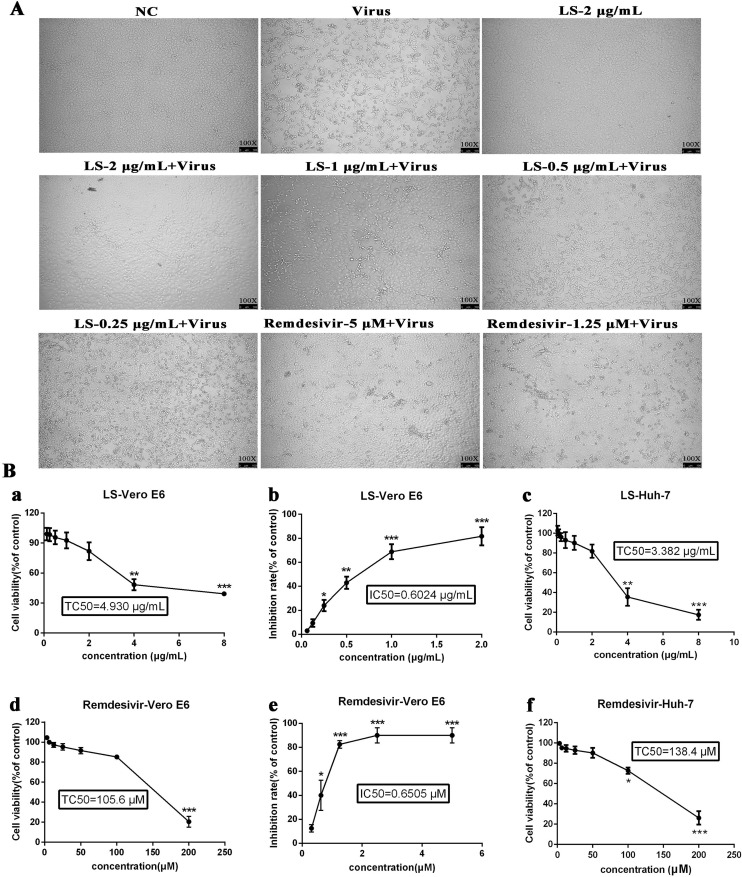

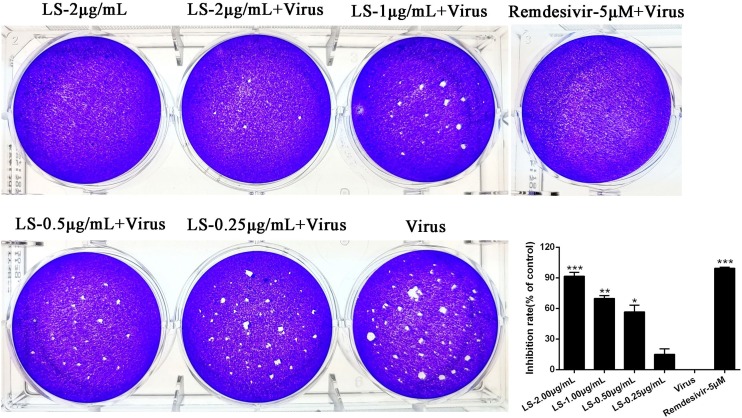

The cytotoxicity of LS in Vero E6 cells was first evaluated by non-radioactive cell proliferation assay (MTT). The TC50 values, corresponding to a 50 % cytotoxic effect after 72 h of inhibitor treatment, were determined. The TC50 of LS and Remdesivir towards Vero E6 cells was 4.930 μg/mL and 105.60 μM, respectively, and the TC50 of LS and Remdesivir towards Huh-7 cells was 3.382 μg/mL and 138.40 μM, respectively (Table 2 ). As shown in Fig. 1 , LS showed unapparent cytotoxicity for the cell lines at concentrations up to 2.0 μg/mL, and Remdesivir was chosen as the positive control and showed no cytotoxicity to cell lines at a concentration of 50 μM. The antiviral activities of LS and Remdesivir against SARS-CoV-2 were evaluated using cytopathic effect (CPE) inhibition assay (Fig. 1) and plaque reduction assay (Fig. 2 ). SARS-CoV-2 caused a severe CPE in Vero E6-infected cells, including cell rounding, detachment and death. A reduction in SARS-CoV-2-induced CPE after 72 h incubation indicated the antiviral activity of LS and Remdesivir. It was found that LS (2 μg/mL, 1 μg/mL and 0.5 μg/mL) and Remdesivir (5 μM and 2.5 μM) significantly reduced the CPE caused by infection in Vero E6 cells, and the IC50 values of LS and Remdesivir were 0.6024 μg/mL and 0.6505 μM, respectively, and the selectivity index (SI) of LS and Remdesivir was 8.18 and 203.84, respectively. The results showed that LS was able to protect cells from virus-induced cell death in a dose-dependent manner.

Table 2.

Inhibitory effect of LS and Remdesivir on coronavirus-infected Vero E6 cells.

| Virus | LS (μg/mL) | Remdesivir (μM) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aTC50 | bIC50 | SI | aTC50 | bIC50 | SI | |

| SARS-CoV-2 | 4.930 | 0.6024 | 8.18 | 105.60 | 0.6505 | 162.34 |

The concentration of LS and Remdesivir required to reduce cell viability by 50 %.

The concentrations of LS and Remdesivir required to inhibit virus proliferation by 50 %; cSelectivity index calculated as ratio of TC50 to IC50.

Fig. 1.

Reduction of SARS-CoV-2-induced cytopathic effect by LS. A. Vero E6 cells were not-infected (NC) or infected with SARS-CoV-2 and the inhibitory effect of LS and Remdesivir on virus proliferation was evaluated. Images under a NiKon Eclipse TE300 microscope (NiKon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) at 100 magnification. B. Inhibiting the activity of SARS-CoV-2 when given different concentrations in vitro. (a) The cytotoxicity effects of LS in Vero E6 cells were detected using MTT assay. (b) The inhibitory effects of LS on SARS-CoV-2 in Vero E6 cells. (c) The cytotoxic effects of LS in Huh-7 cells were detected using MTT assay. (d) The cytotoxic effects of Remdesivir in Vero E6 cells were detected using MTT assay. (e) The inhibitory effects of Remdesivir on SARS-CoV-2 in Vero E6 cells. (f) The cytotoxic effects of Remdesivir in Huh-7 cells were detected using MTT assay. Error bars indicate the range of values obtained from counting in triplicate are represented as the mean ± SD of three individual experiments.

Fig. 2.

Dose-dependent reduction of SARS-CoV-2 plaque formation after treatment with LS. (A) Inhibitory effect of LS or Remdesivir on plaque formation of SARS-CoV-2. (B) The quantitative analysis of the plaque formation in different groups was analysed by SPSS ver. 19.0. Data are presented as the mean ± SD obtained from three separate experiments. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001, compared with SARS-CoV-2-infected cells.

The plaque reduction assay was carried out to confirm the efficacy of LS on SARS-CoV-2 propagation. Vero E6 cells were infected with SARS-CoV-2 (MOI = 0.1) and incubated with overlay medium containing various concentrations of LS. After three days, the overlays were then removed and stained with 0.1 % crystal violet. The plaques were visualized and counted. Remdesivir was used as a positive control at 5 μM. The results showed the average size and plaque number in LS-treated cells were markedly reduced in a dose-dependent manner and LS (2.00, 1.00, 0.50 μg/mL) and Remdesivir (5 μM) could significantly inhibit the viral plaque formation (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2). The above assays showed that LS might be a potential antiviral drug for SARS-CoV-2.

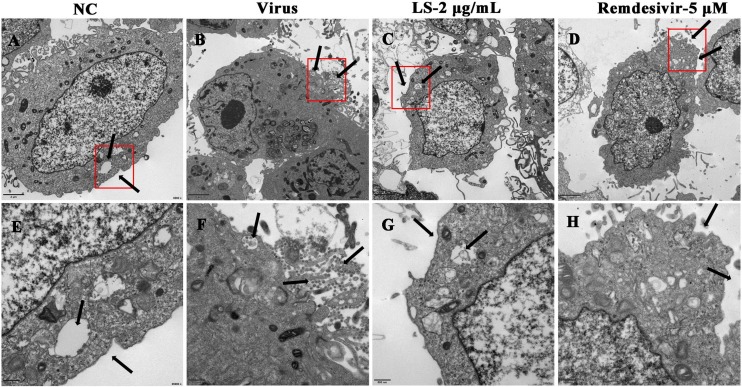

3.2. LS strongly inhibits the virion in Vero E6 cells by TEM

To verify the antiviral efficacy on SARS-CoV-2, TEM assay was performed in the infected-cells which were treated with LS (2.00 μg/mL) or Remdesivir (5 μM) (Fig. 3 ). The results showed that no virus particles were found in the cell control group (NC) (Fig. 3A and E) and many virions were found in the cytoplasm, intracellular vesicles, and cell membrane and presented typical coronavirus morphology in the virus group under electron microscopy after 48 h p.i. (Fig. 3B and F). Treatment with LS (2.00 μg/mL) (Fig. 3C and G) and Remdesivir (5 μM) (Fig. 3D and H) resulted in a reduction of the number of virions and inhibited the entrance into the intracellular vesicles of the virus compared with the virus group.

Fig. 3.

Effect of LS on virus morphology in Vero E6 cells. (A, E) uninfected cells (NC), (B, F) SARS-CoV-2 infected cells (Virus), (C, G) LS-treated infected cells and Remdesivir-treated infected cells. The red boxes and black arrows indicated changes in the number of virus particles after treatment with or without LS and Remdesivir. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article).

3.3. LS strongly inhibits the expression of proinflammatory cytokines in vitro

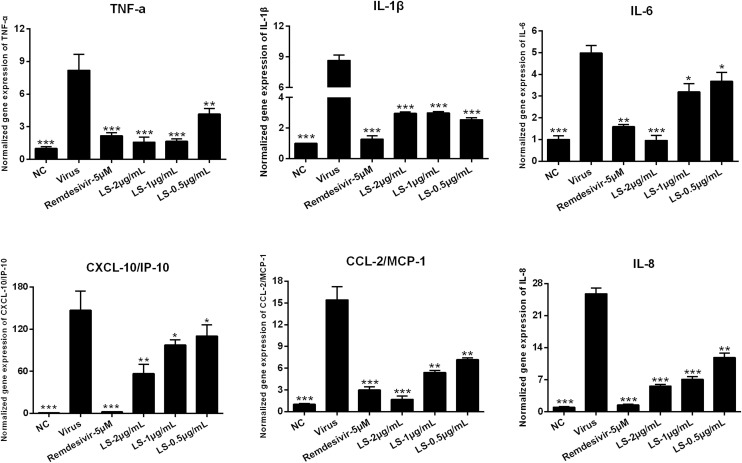

SARS-CoV-2 infection is known to be able to induce a strong inflammatory reaction, hallmarked by the production of cytokines and chemokines. Therefore, the expression of cytokines on the infected cells was measured. To determine the influence of LS or Remdesivir (5 μM) on the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines induced by SARS-CoV-2, the mRNA and protein expression of IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, CXCL10/IP-10, CCL2/MCP-1 and IL-8 in Huh-7 cells were detected by RT-qPCR and ELISA. As shown in Fig. 4, Fig. 5 , the mRNA and protein expression of IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, CXCL10/IP-10, CCL2/MCP-1 and IL-8 in the virus group were significantly up-regulated 48 h after infection in the Huh-7 cells infected by SARS-CoV-2 (p < 0.01) compared with that in the NC group. Compared with the virus group, LS and Remdesivir significantly reduced the mRNA and protein expression of IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, CXCL10/IP-10, CCL2/MCP-1 and IL-8 in a dose-dependent manner in Huh-7 cells 48 h after infection (p < 0.01 or p < 0.05), respectively. This indicated that LS might be an effective anti-inflammatory agent.

Fig. 4.

Effects of treatment with LS or Remdesivir on the mRNA expression levels of inflammatory mediators in SARS-CoV-2-infected Huh-7 cells. TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, CXCL-10/IP-10, CCL-2/MCP-1 and IL-8. Data are presented as the mean ± SD obtained from three separate experiments. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001, compared with SARS-CoV-2-infected cells.

Fig. 5.

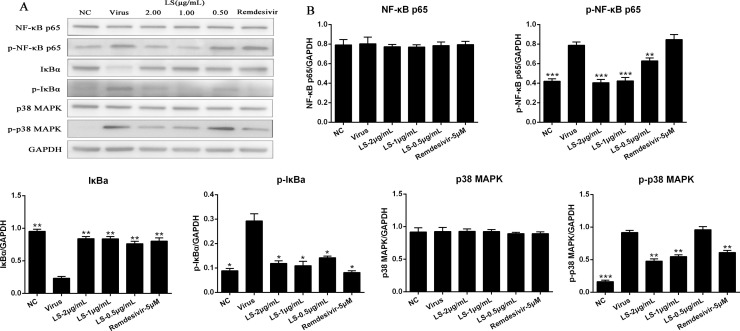

LS inhibited the inflammation induced by the virus through regulating the NF-κB/MAPK signaling pathway in vitro. (A) The protein expressions of NF-κB p65, p-NF-κB p65, p-IκBα, IκBα, p-p38 MAPK and p38 MAPK in the cells was detected by western blot analysis; (B) The quantitative analysis of the NF-κB p65, p-NF-κB p65, p-IκBα, IκBα, p-p38 MAPK and p38 MAPK proteins was analysed by Image J. The values are presented as the means ± SD of three individual experiments. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001, when compared to the viral control.

3.4. LS strongly inhibits the expression of the key proteins related to the NF-κB/MAPK signaling pathway in vitro

To further study whether the antiviral and anti-inflammation mechanisms induced by virus of LS was related to the inhibitory of NF-κB/MAPK signaling pathway activation, the expression of the key proteins related to the NF-κB/MAPK signaling pathway was examined. As shown in Fig. 5, the protein expressions of p-NF-κB p65, p-IκBα, and p-p38 MAPK of the virus group were significantly increased compared with the NC group (p < 0.05), and the expression of IκBα of the virus group were significantly decreased compared with the NC group (p < 0.05). Compared with the virus group, the protein expression of the p-NF-κB p65, p-p38 MAPK and p-IκBα were significantly reduced in Huh-7 cells with LS (2.0, 1.0, and 0.5 μg/mL) and Remdesivir, and IκBα was significantly upregulated, while the expression of NF-κB p65 and p38 MAPK was no significant difference.

4. Discussion

The number of infections caused by SARS-CoV-2 continues to rise sharply in the world [24,25]. The viral infection has widely and rapidly spread worldwide [26]. It is a major coronavirus infection, which threatens human life after SARS and MERS [27]. For this sudden and lethal disease, no specific antiviral drugs or vaccines have been developed, and supportive care and non-specific treatment of patients are currently the only options to ameliorate the symptoms [[28], [29], [30]]. Therefore, effective and safe antiviral agents are urgently needed. Currently, the use of TCM is a popular and acceptable therapy, and many TCM prescriptions have been proven to have obvious therapeutic effect on the virus by inhibiting the replication of the virus directly and improving the immune functions of the host organism. It may be a potential effective drug source for new drug discovery. LS is a TCM used to treat tonsillitis, influenza, pharyngitis, and mumps. However, the antiviral and anti-inflammatory effects induced by SARS-CoV-2 and the potential mechanisms of LS in treating viral pneumonia are less understood. Therefore, the potential antiviral and anti-inflammatory activities of LS induced by SARS-CoV-2 were investigated. In the present study, it was the first time to clarify that LS could not only inhibit SARS-CoV-2 infection, but also significantly suppress the inflammation caused by SARS-CoV-2 through a mechanism that involved the downregulation of inflammatory cytokines.

First, the effects of LS against SARS-CoV-2 in vitro by CPE assay and plaque reduction assay (Fig. 1, Fig. 2) were measured. The results showed that LS was able to protect cells from virus-induced cell death and inhibit the average size and plaque number in LS-treated cells in a dose-dependent manner. The SI index of LS reached 8.18 (Table 1). All these results confirmed that LS might be a potential antiviral drug for SARS-CoV-2. TEM has been a potent tool to observe virus entry, virus particle assembly, viral ultrastructure, and budding from the plasma membrane [31]. To understand the antiviral details of LS, TEM images were taken from each group (Fig. 3). Abundant virus particles assembled at the surface of the membrane, cytoplasm, and plasma vesicles in cells infected with SARS-CoV-2, decreased with the treatment of LS at 2.00 μg/mL.

It is reported that highly pathogenic coronaviruses such as SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV cause fatal pneumonia, which is mainly associated with rapid virus replication, massive inflammatory cell infiltration and elevated proinflammatory cytokine/chemokine responses. Although the pathophysiology of fatal pneumonia caused by highly pathogenic coronaviruses has not been completely understood, recent studies suggest a crucial role of cytokine storm in causing fatal pneumonia [32]. Early studies have shown that increased amounts of proinflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1β, IL-6, CXCL-10/IP-10, and CCL-2/MCP-1) in the serum of SARS patients [33], which was similar to the serum patients with MERS with increased concentrations of proinflammatory cytokines (i.e., IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-15, and IL-17) [34]. It also reported that the expression of the cytokine storm in the NCIP patients in ICU than those in non-ICU patients [7]. Therefore, the mRNA and protein production of IL-1β, TNF-α, CCL-2/MCP-1, CXCL-10/IP-10, IL-6 and IL-8 induced by SARS-CoV-2 was detected. The results showed that LS inhibited the release of IL-1β, TNF-α, CCL-2/MCP-1, CXCL-10/IP-10, IL-6 and IL-8 induced by SARS-CoV-2 in Huh-7 cells (Fig. 4, Fig. 5) in a dose-dependent manner. The change of cytokine profiles suggested that LS might have a potential effect on the inhibition of the cytokine storm induced by SARS-CoV-2.

Since the SARS syndrome is characterized by an uncontrolled inflammatory response and NF-κB is the major transcription factor activated in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [35]. Similar to SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2 can also cause severe respiratory illness and even death. NF-кB plays an important role in mediating inflammation, immune responses, and other cellular activities [36]. Activation of NF-кB can induce cytokines production, and these cytokines can react upon in turn and they produce a positive autoregulatory loop and exacerbate the inflammatory response [37]. Therefore, to understand the molecular mechanism of LS against virus infection, the regulation of the NF-кB/MAPK signaling pathway contributes to the alleviation of inflammation. The results showed that SARS-CoV-2 activated the NF-кB /MAPK signaling pathway and LS could significantly decrease SARS-CoV-2-induced activation of p-NF-κB p65, p-IκBα, and p-p38 MAPK and increase the expression of the IκBα (Fig. 5). We inferred that the underlying mechanism of LS is to impair the upregulated proinflammatory cytokines induced by SARS-CoV-2 via inhibiting the activity of NF-кB/MAPK signaling pathway. The change of cytokine profiles suggested that LS might have a potential effect on the inhibition of cytokine storm induced by SARS-CoV-2.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our results revealed that LS could significantly protect cells from virus-induced cell death and inhibit the average size and plaque number in vitro. The anti-SARS-CoV-2 effect was attributed to the blocking of the proliferation of virus, inhibiting the formation of virus particles, and inhibiting the upregulated expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines induced by SARS-CoV-2 via regulating the activity of NF-кB/MAPK signaling pathway. These findings warrant further evaluation of LS as a potential agent for SARS-CoV-2 treatment and provide information to further reveal the mechanisms. LS may be an effective anti-inflammatory agent and can be used to treat the inflammation induced by SARS-CoV-2.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Department of Education of Guangdong Provincial (2020KZDZX1159), Macao Science and Technology Development Fund (0172/2019/A3), Science Research Project of the Guangdong Province (Nos. 2020B111110001), National Key Technology R&D Program (2018YFC1311900) and Guangdong Science and Technology Foundation (2019B030316028).

References

- 1.Ksiazek T.G., Erdman D., Goldsmith C.S., Zaki S.R., Peret T., Emery S., Tong S., Urbani C., Comer J.A., Lim W., Rollin P.E., Dowell S.F., Ling A., Humphrey C.D., Shieh W., Guarner J., Paddock C.D., Rota P., Fields B., DeRisi J., Yang J., Cox N., Hughes J.M., LeDuc J.W., Bellini W.J., Anderson L.J. A novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:1953–1966. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zaki A.M., van Boheemen S., Bestebroer T.M., Osterhaus A.D., Fouchier R.A. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;367:1814–1820. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Du Toit A. Outbreak of a novel coronavirus. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41579-020-0332-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carlos W.G., Dela Cruz C.S., Cao B., Pasnick S., Jamil S. Novel Wuhan (2019-nCoV) coronavirus. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020 doi: 10.1164/rccm.2014P7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nkengasong J. China’s response to a novel coronavirus stands in stark contrast to the 2002 SARS outbreak response. Nat. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0771-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou P., Yang X.L., Wang X.G., Hu B., Zhang L., Zhang W., Si H.R., Zhu Y., Li B., Huang C.L. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y., Zhang L., Fan G., Xu J., Gu X., Cheng Z., Yu T., Xia J., Wei Y., Wu W., Xie X., Yin W., Li H., Liu M., Xiao Y., Gao H., Guo L., Xie J., Wang G., Jiang R., Gao Z., Jin Q., Wang J., Cao B. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C., Zhu F., Liu X., Zhang J., Wang B., Xiang H., Cheng Z., Xiong Y., Zhao Y. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel Coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu P., Hao X., Lau EHY Wong J.Y., Leung KSM Wu J.T., Cowling B.J., Leung G.M. Real-time tentative assessment of the epidemiological characteristics of novel coronavirus infections in Wuhan, China, as at 22 January 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020;25(3) doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.3.2000044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zumla A., Chan J.F., Azhar E.I., Hui D.S., Yuen K.Y. Coronaviruses-drug discovery and therapeutic options. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2016;15:327–347. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2015.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tian Li, Wang Zhiyong, Wu Hao, Wang Song, Wang Ye, Wang Yanyan, Xu Jingwei, Wang Liying, Qi Fengchun, Fang Minli, Yu Dahai, Fang Xuexun. Evaluation of the anti-neuraminidase activity of the traditional Chinese medicines and determination of the anti-influenza A virus effects of the neuraminidase inhibitory TCMs in vitro and in vivo. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011;137(1):534–542. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo H., Zhang Q.H., Yang J., Gong J.N., Zhao Y.S., Zhou X.P. Effect of Lianhua Qingwen capsule on immunity of mice infected with flu virus. J. Nanjing Univ. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2007;23:106–108. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma Q., Liang D., Song S., Yu Q., Shi C., Xing X., Luo J.B. Comparative study on the antivirus activity of Shuang-Huang-Lian injectable powder and its bioactive compound mixture against human adenovirus III in vitro. Viruses. 2017;9:1–12. doi: 10.3390/v9040079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wan M., Liu Y.P. Pharmacological study of liushen pill. Chin. Remedies Clin. 2011;11:935–936. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ren R.J., Huang J.F. The research of Liu shen pills. Chinese Traditional Patent Medicine. 1987:32–34. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang M.Z., Chen M., Hunag G.H., Zhu Z., Xiao Y., Liu H.F., Luo C.Y., Xu W.B., Wang C.X. Study on the effect of Liushen pill anti-adenovirus in vitro. Chin. J. Exp. Clin. Virol. 2014;28:47–49. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma Q., Huang W., Zhao J., Yang Z. Liu Shen Wan inhibits influenza a virus and excessive virus-induced inflammatory response via suppression of TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway in vitro and in vivo. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020;21:252. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2020.112584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Q., Luo N.C., Dai J.J., Di L.Q., Wang H.B., Yang Y.Q., Li J.S., Xin Y., Li X.D., Qu Y.L., Lou J.W., Pang Y.Z. (2019), A method for detecting the Liu Shen pill by HPLC. Chinese patent CN20191012362.8.

- 19.Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W., Li X., Yang B., Song J., Zhao X., Huang B., Shi W., Lu R., Niu P., Zhan F., Ma X., Wang D., Xu W., Wu G., Gao G.F., Tan W. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382(8):727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park K.I., Park H.S., Kang S.R., Nagappan A., Lee D.H., Kim J.A., Han D.Y., Kim G.S. Korean Scutellaria baicalensis water extract inhibits cell cycle G1/S transition by suppressing cyclin D1 expression and matrix-metalloproteinase-2 activity in human lung cancer cells. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011;133:634–641. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.10.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reed L.J., Muench H. A simple method of estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1938;27:493–497. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pfaffl M.W. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Apelian Z., Hong L.C., Seto J.T. Scanning electron microscope examination of epithelial cells infected with enveloped viruses. J. Viol. Methods. 1984;8:147–154. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(84)90048-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.CDC, China . 2020. Distribution of 2019-nCoV Infection.http://2019ncov.chinaC.D.C.n/2019-nCoV/ [Google Scholar]

- 25.WHO . 2020. Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Situation report-27 Feb 17.https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200216-sitrep-27-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=78c0eb78_2 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guan W.J., Ni Z.Y., Hu Y., Liang W.H., Ou C.Q., He J.X., Liu L., Shan H., Lei C.L., Hui DSC Du B., Li L.J., Zeng G., Yuen K.Y., Chen R.C., Tang C.L., Wang T., Chen P.Y., Xiang J., Li S.Y., Wang J.L., Liang Z.J., Peng Y.X., Wei L., Liu Y., Hu Y.H., Peng P., Wang J.L.M., Liu J.Y., Chen Z., Li G., Zheng Z.J., Qiu S.Q., Luo J., Ye C.J., Zhu S.Y., Zhong N.S. China Medical Treatment Expert Group for Covid-19., clinical characteristics of 2019 novel coronavirus infection in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;2(28) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mahase E. China coronavirus: WHO declares international emergency as death toll exceeds 200. Bmj. 2020;368:m408. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Guangdi, De Clercq Erik. Therapeutic options for the 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2020 doi: 10.1038/d41573-020-00016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Russell C.D., Millar J.E., Baillie J.K. Clinical evidence does not support corticosteroid treatment for SARS-CoV-2 lung injury. Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30317-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zumla A., Hui D.S., Azhar E.I., Memish Z.A., Maeurer M. Reducing mortality from: host-directed therapies should be an option. Lancet. 2020;22:395. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30305-6. (10224) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goldsmith C.S., Miller S.E. Modern uses of electron microscopy for detection of viruses. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2009;22(4):552–563. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00027-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Channappanavar R., Perlman S. Pathogenic human coronavirus infections: causes and consequences of cytokine storm and immunopathology. Semin. Immunopathol. 2017;39(5):529–539. doi: 10.1007/s00281-017-0629-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leong H.N., Chan K.P., Oon L.L., Koay E., Ng L.C., Lee M.A., Barkham T., Chen M.I., Heng B.H., Ling A.E. Clinical and laboratory findings of SARS in Singapore. Ann. Acad. Med. Singapore. 2006;35(5):332–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Assiri A., Al-Tawfiq J.A., Al-Rabeeah A.A., Al-Rabiah F.A., Al-Hajjar S., Al-Barrak A., Flemban H. Epidemiological, demographic, and clinical characteristics of 47 cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus disease from Saudi Arabia: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2013;13(9):752–761. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70204-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fan J., Ye R.D., Malik A.B. Transcriptional mechanisms of acute lung injury. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2001;281:1037–1050. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.281.5.L1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mitchell S., Vargas J., Hoffmann A. Signaling via the NF-κB system. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Syst. Biol. Med. 2016;8:227–241. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Santoro M.G., Rossi A., Amici C. NF-κB and virus infection: who controls whom. EMBO J. 2003;22:2552–2560. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]