Abstract

Backgrounds.

The extent to which psychiatric disorders are associated with an increased risk of violence to partners is unclear. This review aimed to establish risk of violence against partners among men and women with diagnosed psychiatric disorders.

Methods.

Systematic review and meta-analysis. Searches of eleven electronic databases were supplemented by hand searching, reference screening and citation tracking of included articles, and expert recommendations.

Results.

Seventeen studies were included, reporting on 72 585 participants, but only three reported on past year violence. Pooled risk estimates could not be calculated for past year violence against a partner and the three studies did not consistently report increased risk for any diagnosis. Pooled estimates showed an increased risk of having ever been physically violent towards a partner among men with depression (odds ratio (OR) 2.8, 95% confidence intervals (CI) 2.5–3.3), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) (OR 3.2, 95% CI 2.3–4.4) and panic disorder (OR 2.5, 95% CI C% 1.7–3.6). Increased risk was also found among women with depression (OR 2.4, 95% CI 2.1–2.8), GAD (OR 2.4, 95% CI 1.9–3.0) and panic disorder (OR 1.9, 95% CI 1.4–2.5).

Conclusions.

Psychiatric disorders are associated with high prevalence and increased odds of having ever been physically violent against a partner. As history of violence is a predictor of current violence, mental health professionals should ask about previous partner violence when assessing risk.

Key words: Aggression, domestic violence, mental disorders, violence

Introduction

Mental illness is known to be associated with an increased risk of violence to others. People with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder are nearly twice as likely to perpetrate violence against others as those without mental disorders, but much of this excess risk is explained by substance misuse, and accounts for a small proportion of violence in the community (Walsh et al. 2002; Fazel et al. 2009, 2010). The literature has focused on the extent and correlates of violence perpetrated by people with severe mental illness (SMI), but little is known about who this violence is directed against, or about the risks posed by people with common mental disorders (CMD), limiting our ability to develop effective interventions. Specifically, the extent to which psychiatric disorders are associated with an increased risk of violence to partners is unclear. Indeed, we are not aware of any previous reviews on the risk of violence to partners from the substantial body of research on interpersonal violence perpetrated by people with psychiatric disorders.

Violence against partners is likely to have a different time course and profile of risk factors and consequences than violence against strangers and acquaintances, and hence is likely to require distinct interventions (Krug et al. 2002). Although stranger violence tends to be sporadic, partner violence is usually recurrent, and has an impact not only on the couple themselves, but also on any dependant children (World Health Organization and London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, 2010). Partner violence is a heterogeneous phenomenon, which tends to occur either as a pattern of abusive, controlling behaviour or as a maladaptive way of coping with stressful situations in a relationship (without the central feature of coercive control) (Johnson & Leone, 2005). Risk factors for both of these patterns of partner violence include childhood abuse, witnessing parental domestic violence, social deprivation, substance misuse and violent victimization (World Health Organization and London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, 2010). These factors are also associated with psychiatric disorders, both CMDs (e.g. anxiety and mild/moderate depression) and SMI (e.g. schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and severe recurrent depression) (Read et al. 2005; Hovens et al. 2010). There may therefore be an indirect association between mental illness and partner violence via one or more of these risk factors (Hiday et al. 2002; Swanson et al. 2002; Rosenberg et al. 2007). In addition, the symptoms of mental illness may directly increase the risk (e.g. irritability during a manic episode, suspiciousness and hostility during a psychotic episode), and risk may vary across diagnoses. Identifying the extent to which different mental disorders are associated with violence against a partner is important since it would inform violence prevention efforts.

Aims of the study:

This systematic review aimed to establish:

-

(a)

The prevalence of violence against a partner among men and women with diagnosed psychiatric disorders.

-

(b)

The risk of violence against a partner among men and women with diagnosed psychiatric disorders compared with controls.

Methods

Search strategy

This review followed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) and Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines and the protocol is registered with Prospero: registration CRD42012002048 (www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero) (Stroup et al. 2000; Moher et al. 2009) A completed PRISMA checklist is available as supplementary material. We undertook electronic searches of eleven bibliographic databases (see supplementary material), updated two systematic reviews on violence perpetration by people with mental disorders (i.e. which did not report on violence perpetrated by partners) to identify studies which may have collected data on violence perpetrated against a partner (Fazel et al. 2009, 2010), hand searched three journals (Aggression and Violent Behaviour, Journal of Family Violence and Journal of Interpersonal Violence), screened reference lists of included studies, conducted forwards citation tracking of included studies, and contacted experts for recommendations. Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and text words were used for electronic database searches, from their dates of inception up to 31st January 2012. Terms for partner violence were adapted from Cochrane protocols and literature reviews (Ramsay et al. 2002, 2009; Dalsbo & Johme, 2006) terms for mental disorders were adapted from National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines (see supplementary information) (NICE, 2008). When updating the reviews on violence perpetration, we used the author's original search terms to search databases from February 2009 (the upper limit of the original review) to 31st January 2012 (Fazel et al. 2009, 2010). Fifty experts were contacted with a list of included studies and were asked to nominate additional papers (either published or in press) that may have been eligible for inclusion in the review; responses were received from 29. Only English language papers were included.

Study selection criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they: (a) included men and/or women (aged ≥16 years), (b) measured psychiatric disorder using a validated diagnostic instrument (e.g. the Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry) (Wing, 1994); (c) recruited participants from clinical, community or general population settings; (d) presented the results of peer-reviewed research based on intervention studies (e.g. randomized controlled trials, non-randomized controlled trials and parallel group studies), before-and-after studies, interrupted time series studies, cohort studies, case-control studies or cross-sectional studies; and (e) reported the prevalence and/or risk of perpetration of violence against a partner, or collected data from which these statistics could be calculated. Partner violence was defined ‘physical, sexual and/or psychological abuse to an individual perpetrated by a current or former intimate partner’, as per American Medical Association guidelines (American Psychiatric Association, 1992). The full definition of psychiatric disorder used in this review is provided in the Supplementary Material.

Data extraction and quality appraisal

Three reviewers screened titles and abstracts against the inclusion criteria; if it was unclear whether a reference met the inclusion criteria, it was taken forward to the next stage of screening. Reviewers then assessed full texts of potentially eligible studies. If studies collected data on the prevalence and/or risk of violence perpetration against a partner but did not report it, authors were contacted.

Data from included papers were extracted onto standardized electronic forms by three reviewers. Extracted data included information on study designs, sample characteristics, measures of mental disorder and violence perpetration and the prevalence and risk of perpetration of violence against a partner. Data were extracted separately for men and women.

The quality of included studies was independently appraised by two reviewers using criteria adapted from validated tools (Wing, 1994; Downs & Black, 1998; Loney & Chambers, 2000; Saha et al. 2005). Reviewers compared scores and resolved disagreements before allocating a final appraisal score. The quality appraisal checklist included items assessing study selection and measurement biases (see supplementary material). Studies were categorized as high quality if they scored ≥50% on questions pertaining to selection bias. This criterion was chosen in order to maximize the number of studies eligible for inclusion in the meta-analysis while excluding studies in which a high risk of selection bias threatened the validity of the results.

Data synthesis

Prevalence, odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for perpetration of physical violence by type of mental disorder among men and women. If studies measured one disorder only, the control group for the calculation of risk estimates were participants without that disorder. If studies measured multiple disorders and thus contributed to estimates of violence perpetration across several mental disorders, the control groups were participants without those mental disorders. Owing to limited data, it was not possible to adjust ORs for potential confounders; unadjusted ORs are therefore presented.

Pooled unadjusted OR estimates (with corresponding 95% CI) of perpetration of physical violence against partners by type of mental disorder were calculated if data were available from three or more high-quality studies. Pooled ORs were calculated separately for men and for women; studies for which gender-disaggregated data were not available and were not eligible for inclusion in the meta-analyses. Heterogeneity was estimated using the I2 statistic (associated 95% CIs were calculated using a non-central χ2 based approach); as an indicator I2 values of 25–50%, 50–75% and ≥75% represent ‘low’, ‘moderate’ and ‘high’ heterogeneity, respectively (Higgins & Thompson, 2002; Harris et al. 2008). DerSimonian–Laird random effects models were used (DerSimonian & Laird, 1986). Owing to the small number of studies included in each meta-analysis, it was not possible to use meta-regression to investigate sources of heterogeneity; analyses were instead manually checked. Sensitivity analyses were conducted in order to assess the impact of excluding low-quality papers from pooled estimate calculations. We also examined the influence of individual studies on summary effect estimates by conducting influence analyses, which compute summary estimates omitting one study at a time. We aimed to use Egger's test to estimate risk of study bias with funnel plots (Egger et al. 1997). However, due to the small number of eligible studies (<10 per meta-analysis), tests for funnel plot asymmetry could not be conducted and visual inspections of the plots were not meaningful (Sterne et al. 2011). Funnel plots are therefore not presented. All analyses were conducted in STATA 11 (StataCorp, 2009).

Results

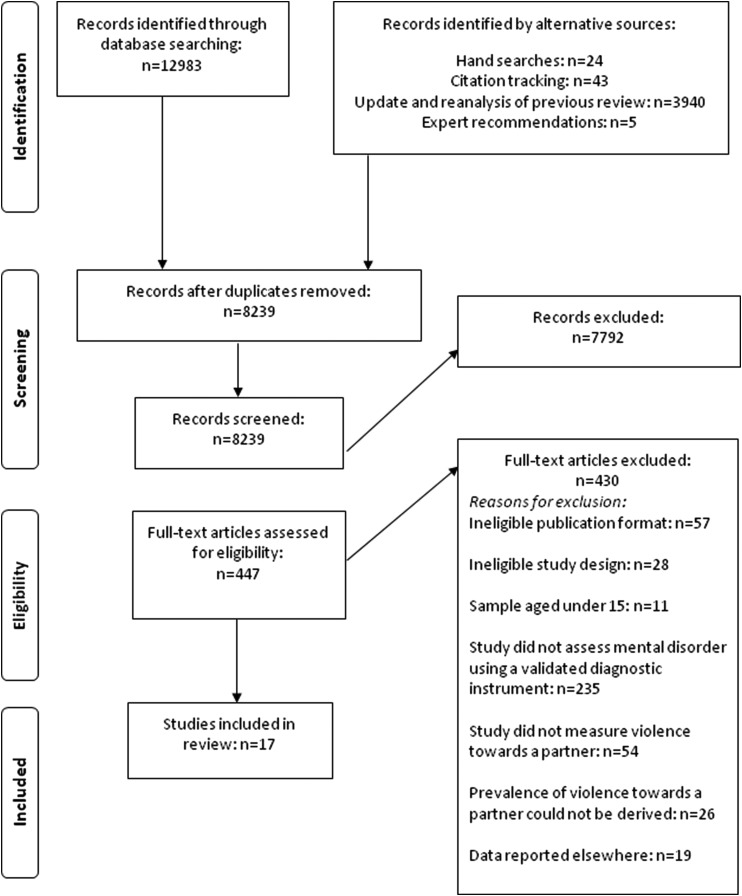

Literature searches yielded 8239 unique references; 7792 were excluded following title and abstract screening and a further 430 were excluded following full-text screening. Details of the 430 papers excluded after full-text screening, and reasons for exclusion, are available upon request. Seventeen papers were included in the review (see Fig. 1), reporting on 72 585 participants. Thirteen papers were identified during searches of electronic databases, three during citation tracking, one during the update of the reviews on violence perpetration (Fazel et al. 2009, 2010) and none from expert recommendations or hand searches.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of screened and included papers.

Key features of included studies

Key characteristics of all included studies are summarized in Table 1. Additional detail for all included studies, including outcomes and quality appraisal scores are reported by disorder in the supplementary material. Ten studies were conducted in non-clinical settings (Swanson et al. 1990; Kessler et al. 1994, 2005; Danielson et al. 1998; Fergusson et al. 2005; Taft et al. 2007; O'Leary et al. 2008; McManus et al. 2009; Gass et al. 2011), six in clinical settings (Parrott et al. 2003; Najavits et al. 2004; Grant & Kaplan, 2005; Taft et al. 2009, 2010; Friedman et al. 2011; Yang et al. 2012) and one was in both clinical and non-clinical settings (Sippel & Marshall, 2011). Thirteen studies were categorized as high quality. Unless otherwise stated, results are reported for high-quality studies only and neither the exclusion of poor quality studies nor sensitivity analyses made material differences to odds estimates.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies (n = 17)*

| Total (n = 17) | Past year violence against a partner (n = 6) | Lifetime violence against a partner (n = 11) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample: | |||

| Males only | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Females only | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Males and females | 13 | 6 | 7 |

| Diagnoses: | |||

| Schizophrenia and non-affective psychosis | 9 | 6 | 3 |

| Bipolar affective disorder | 9 | 1 | 8 |

| Depressive disorders | 22 | 8 | 14 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 8 | 3 | 5 |

| PTSD | 14 | 2 | 12 |

| Panic disorders | 17 | 6 | 11 |

| Social phobia | 5 | 1 | 4 |

| Agoraphobia | 4 | 1 | 3 |

| OCD | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Eating disorder | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Type of violence | |||

| Physical | 16 | 5 | 10 |

| Psychological | 5 | 2 | 3 |

| Sexual | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Physical, sexual or psychological (combined) | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Measurement of violence: | |||

| Validated instruments (unmodified) | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Validated instruments (modified) | 10 | 5 | 5 |

| Non-validated instruments | 4 | 1 | 3 |

| Items from DIS/SCID schedules | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Setting: | |||

| Clinical only | 7 | 3 | 4 |

| Non-clinical only | 10 | 3 | 7 |

| Clinical and non-clinical | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Region: | |||

| North America | 12 | 3 | 9 |

| Central America | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| South America | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Europe | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Africa | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Asia | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Australasia | 2 | 2 | 0 |

OCD, obsessive compulsive disorder; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

Categories are not mutually exclusive and rows may therefore add to >17.

Results are presented as follows: (a) prevalence and risk of past year perpetration of physical violence against a partner among people with SMI (schizophrenia, non-affective psychosis and bipolar disorder) and people with CMD (depression, dysthymia, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), panic disorder and social phobia) and (b) prevalence and risk of lifetime physical violence against a partner among people with SMI and people with CMD.

Prevalence and odds of violence perpetrated against a partner by men and women with psychiatric disorders

Tables 2 and 3 report the median prevalence and pooled OR estimates of past year and lifetime physical violence perpetration against a partner by psychiatric disorder, for men and women, respectively. If median prevalence could not be calculated, prevalence estimates from individual studies are shown. Where pooled OR estimates could not be calculated, the direction of risk reported by individual studies is shown. Owing to a lack of data, prevalence and risk estimates for other types of violence (e.g. psychological violence, sexual violence or combinations of physical, sexual and/or psychological violence) are presented as supplementary information only.

Table 2.

Median prevalence and pooled OR of perpetrating physical violence against a partner among men with psychiatric disorder (high-quality studies only)

| Past year perpetration | Lifetime perpetration | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence | OR | Prevalence | OR | |||||

| Disorder | Median (IQR, range) | Individual study estimates (where median prevalence could not be calculated) | Pooled OR | OR reported as increased (+), decreased (−) or no different (=) (where pooled OR could not be calculated) | Median prevalence (IQR, range) | Individual study estimates (where median prevalence could not be calculated) | Pooled OR | OR reported as increased (+), decreased (−) or no different (=) (where pooled OR could not be calculated) |

| No disorder (reference group) | – | Danielson et al. (1998) 15.0% (n = 293) O'Leary et al. (2008) 16.9% (n = 473) |

n/a | n/a | 4.0% (IQR 3.3–6.8%; range 2.8–13.4% |

– | n/a | n/a |

| Bipolar affective disorder | – | Yang et al. (2012) 18.2% (n = 11) | – | – | 18.6% (IQR 16.7–27.1%; range 14.7–35.5%) | – | – | Grant & Kaplan 2005 (+) Kessler et al. (1994) (=) Kessler et al. (2005) (+) |

| Schizophrenia and non-affective psychosis | – | Danielson et al. (1998) 31.8% (n = 22) Yang et al. (2012) 7.2% (n = 83) |

– | Danielson et al. (1998) (=) | – | Kessler et al. (1994) 100% (n = 17) | – | – |

| Depression | 17.8% (IQR 16.6–20.8%, range 15.4–23.7%) | – | – | Danielson et al. (1998) (=) O'Leary et al. (2008) (=) |

18.3% (IQR 15.1–21.5%;range 13.1–22.5%) | – | 2.8 (95% CI 2.5–3.3), I2 = 60.2% | – |

| Dysthymia | – | O'Leary et al. (2008) 0% (n = 9) | – | – | 16.63% (IQR 15.6–17.4%; range 14.6–18.1%) | – | Kessler et al. (1994) (=) Kessler et al. (2005) (=) |

|

| GAD | – | Danielson et al. (1998) 40.0% (n = 65) O'Leary et al. (2008) 14.3% (n = 7) |

– | Danielson et al. (1998) (+) O'Leary et al. (2008) (=) |

20.2% (IQR 19.2–23.4%; range 17.3–31.9%) | 3.2 (95% CI 2.3–4.4), I2 = 78.4% | – | |

| PTSD | O'Leary et al. (2008) 27.3% (n = 11) | O'Leary et al. (2008) (=) | 22.3% (IQR 17.7–27.6%; range 27.3–86%). | – | 1.8 (95% CI 1.0–3.2), I2 = 29.8% | – | ||

| Panic disorder | – | O'Leary et al. (2008) 28.6% (n = 7) | – | O'Leary et al. (2008) (=) | 14.4% (IQR 13.0–18.6%; range 12.2–27.7%) | 2.5 (95% CI 1.7–3.6), I2 = 39.% | – | |

| Social phobia | – | O'Leary et al. (2008) 78.6% (n = 14) | – | O'Leary et al. (2008) (+) | 20.7% (IQR 16.1–26.3%; range 11.1–34.8%). | 2.8 (95% CI 2.4–3.2), I2 = 90.3% | – | |

| Agoraphobia | – | O'Leary et al. (2008) 100% (n = 2) | – | – | – | Kessler et al. (1994) 22.1% (n = 33) McManus (2009) 32.5% (n = 29) |

– | Kessler et al. (1994) (=) McManus 2009 (+) |

| OCD | – | – | – | – | McManus (2009) 21.3% (n = 32) | – | McManus et al. (2009) (+) | |

| Eating disorder | – | Danielson et al. (1998) 50% (n = 2) | – | – | – | Kessler et al. (2005) 8.9% (n = 11) | – | – |

GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; OCD, obsessive compulsive disorder; OR, odds ratios; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

Table 3.

Median prevalence and pooled odds of perpetrating physical violence against a partner among women with psychiatric disorder (high-quality studies only)

| Past year perpetration | Lifetime perpetration | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence | OR | Prevalence | OR | |||||

| Disorder | Median (IQR, range) | Individual study estimates (where median prevalence could not be calculated) | Pooled OR | OR reported as increased (+), decreased (−) or no different (=) (where pooled OR could not be calculated) | Median (IQR, range) | Individual study estimates (where median prevalence could not be calculated) | Pooled OR | OR reported as increased (+), decreased (−) or no different (=) (where pooled OR could not be calculated) |

| No. disorder (reference group) | – | Danielson et al. (1998) 29.3% (n = 263) O'Leary et al. (2008) 18.1% (n = 426) |

n/a | n/a | 7.4% (IQR 3.3–12.3%; range 2.0–15.8% | n/a | n/a | |

| Bipolar affective disorder | – | – | – | 29.5% (IQR 29–33.1%, range 28.4–36.7%) | – | Grant 2005 (+) Kessler et al. (1994) (=) Kessler et al. (2005) (+) |

||

| Schizophrenia and non-affective psychosis | – | Danielson 50.0% (n = 16) Yang et al. (2012) 18.8% (n = 32) |

– | Danielson et al. (1998) (=) | – | Kessler et al. (1994) 21.0% (n = 72) | – | Kessler et al. (1994) (=) |

| Depression | 33.3% (IQR 26.4–42.3%, range 19.5–51.3%) | – | – | Danielson et al. (1998) (+) O'Leary et al. (2008) (=) |

18.8% (IQR 14.9–23.5%; range 9.6–31.6%) | – | 2.4 (95% CI 2.1–2.8), I2 = 67.7% | – |

| Dysthymia | – | O'Leary et al. (2008) 13.3% (n = 15) | – | – | 26.0% (IQR 20.4–31.4%, range 14.8–36.8%) | 1.8 (95% CI 1.2–2.7), I2 = 51.4% | – | |

| GAD | – | Danielson et al. (1998) 42.3% (n = 130) O'Leary et al. (2008) 18.8% (n = 16) |

– | Danielson et al. (1998) (+) O'Leary et al. (2008) (=) |

20.7% (IQR 15.1–24.8%, range 10.2–25.3%) | 2.4 (95% CI 1.9–3.0), I2 = 57.1% | – | |

| PTSD | – | O'Leary et al. (2008) 8% (n = 25) | – | O'Leary et al. (2008) (=) | – | Kessler et al. (1994) 22.1% (n = 85) Kessler et al. (2005) 15.1% (n = 63) |

– | Kessler et al. (1994) (=) Kessler et al. (2005) (+) |

| Panic disorder | – | O'Leary et al. (2008) 16.7% (n = 18) | – | O'Leary et al. (2008) (=) | 22.8% (IQR 21.0–28.0%, range 20.0–39.5%) |

1.9 95% CI 1.4–2.5), I2 = 70.5% |

– | |

| Social phobia | O'Leary et al. (2008) 47.6% (n = 21) | O'Leary 2008 (+) | 22.2% (IQR 16.7–31.7%, range 14.6–45.6%) |

2.3 (2.1–2.7), I2 = 90.5% | ||||

| Agoraphobia | – | O'Leary et al. (2008) 50% (n = 2) | – | – | – | Kessler et al. (1994) 29.7% (n = 85) McManus (2009) 43.0% (n = 57) |

– | Kessler et al. (1994) (+) McManus et al. (2009) (+) |

| OCD | – | – | – | – | McManus (2009) 36.2% (n = 49) | – | McManus et al. (2009) (+) | |

| Eating disorder | – | Danielson et al. (1998) 63.6% (n = 11) | – | Danielson et al. (1998) (+) | – | Kessler et al. (2005) 12.5% (n = 14) | – | – |

GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; OCD, obsessive compulsive disorder; OR, odds ratio; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

Past year physical violence against a partner

Data on the past year perpetration of physical violence against a partner were limited; three high-quality studies provided usable data. Yang et al. followed up US psychiatric inpatients 1 year post-discharge, and included men and women with bipolar disorder, schizophrenia and depression (Yang et al. 2012). Danielson et al. analysed data from the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study, conducted in New Zealand with a community sample, and collected data from men and women with non-affective psychosis, depression and GAD (Danielson et al. 1998). O'Leary et al. conducted a nationally representative survey in Ukraine that included a small number of men and women with CMD (O'Leary et al. 2008). In the latter two studies, the prevalence of past year physical violence against a partner among people with no psychiatric disorder ranged from 15.0 to 16.9% among men and from 18.1 to 29.3% among women (Danielson et al. 1998; O'Leary et al. 2008).

SMI: Two studies reported on men and women's perpetration of past year physical violence against a partner (Danielson et al. 1998; Yang et al. 2012). Median prevalence and pooled risk estimates could not be calculated. Tables 2 and 3 report prevalence estimates from individual studies. Risk statistics could be calculated for Danielson et al. only, which found no increase in risk of violence among men or women with non-affective psychosis compared with men and women with no psychiatric disorder (Danielson et al. 1998).

CMD: Median prevalence estimates of the perpetration of physical violence against a partner in the past year could be calculated for depression only. A higher median prevalence was reported for women with depression (33.3% Inter Quartile Range (IQR), 26.4–42.3%) than for men with depression (17.8%, IQR 16.6–20.8%) (see Tables 2 and 3). Pooled risk estimates could not be calculated. Among women with depression, an increased risk of past year perpetration of physical violence against a partner was reported by Danielson et al. (OR 2.5, 95% CI 1.6–4.1) but not by O'Leary et al. Neither study reported an increased risk for men with depression. As shown in Tables 2 and 3, risk estimates for other CMDs also varied between studies, gender and type of disorder.

Lifetime physical violence against a partner

Data on the lifetime perpetration of violence against a partner were drawn predominantly from five household surveys, conducted in the USA (Kessler et al. 1994, 2005; Grant & Kaplan, 2005), the UK (McManus et al. 2009) and South Africa (Gass et al. 2011). In these studies, the median prevalence of lifetime physical violence against a partner among people with no psychiatric disorder was 4.0% (IQR 3.3–6.8%, range 2.8–13.4%) for men and 7.4% (IQR 3.3–12.3%, range 2.0–15.8%) for women.

SMI: Very few studies reported prevalence or risk estimates for lifetime physical violence against a partner among men or women with schizophrenia or non-affective psychosis. Median prevalence and pooled risk estimates could not be calculated; Tables 2 and 3 report prevalence estimates from individual studies. Among men and women with bipolar disorder, the median prevalence of lifetime physical violence against a partner was 18.6% (IQR 16.7–27.1%; range 14.7–35.5%) and 29.5% (IQR 29.0–33.1%, range 28.4–36.7%), respectively. Two community surveys conducted in the USA found an increased risk of violence of having ever been physically violent against a partner among both men and women with bipolar disorder compared with those with no psychiatric disorder (Grant & Kaplan, 2005; Kessler et al. 2005), while a third found no significant risk difference (Kessler et al. 1994).

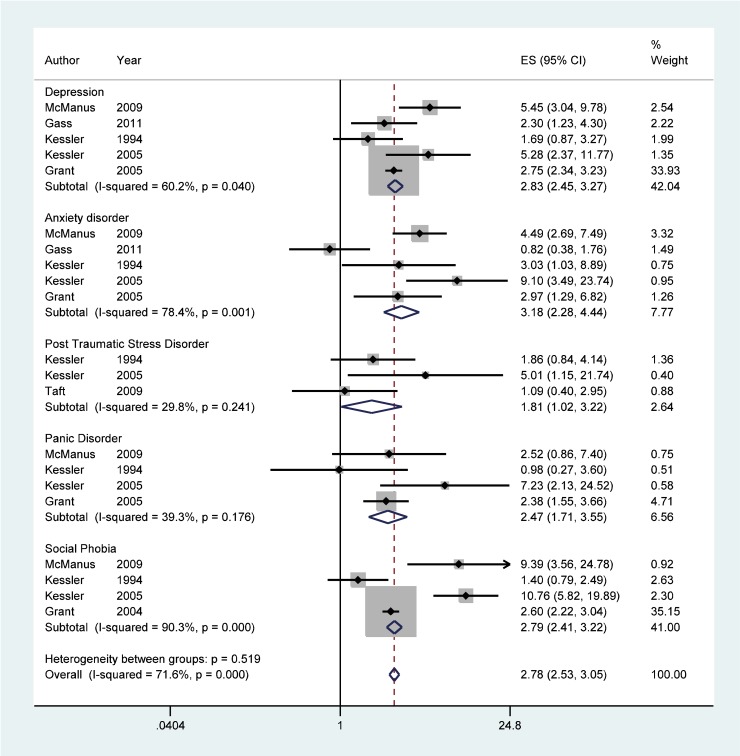

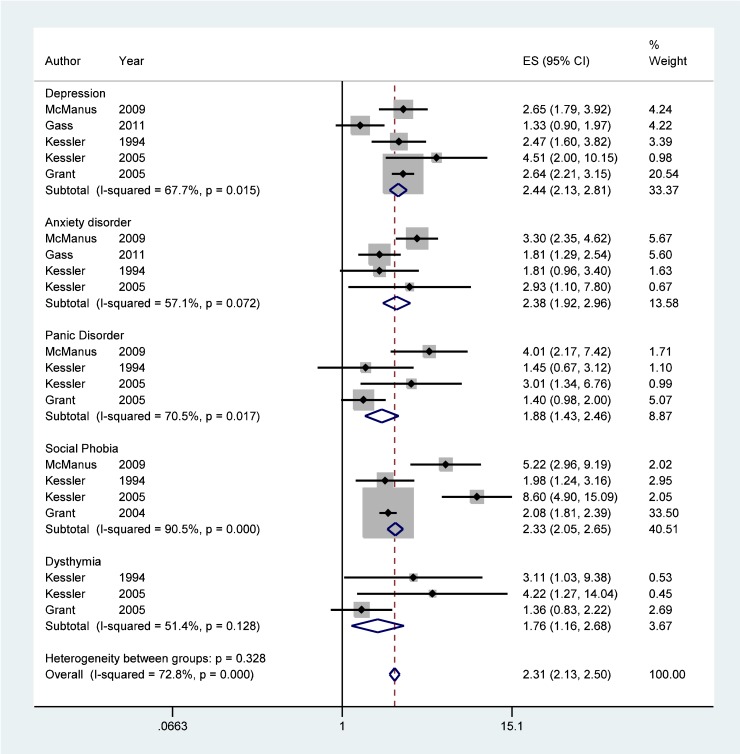

CMD: The median prevalence of lifetime physical violence perpetrated against a partner was similar across disorders, ranging from 14.4 to 26.0%, and between men and women (see Tables 2 and 3). Pooled risk estimates suggested, however, that compared with men and women with no psychiatric disorder, the risk of lifetime physical violence against a partner was slightly higher among men with CMD than among women with CMD (see Figs 2 and 3, and Tables 2 and 3). I2 statistics generally indicated low to moderate between-study heterogeneity; high heterogeneity was observed in the meta-analysis of risk of lifetime violence against a partner among men with GAD, and both men and women with social phobia.

Fig. 2.

Forest plot displaying DerSimonian and Laird weighted random-effect pooled odds estimates for lifetime physical violence against a partner by men with diagnosed psychiatric disorders.

Fig. 3.

Forest plot displaying DerSimonian and Laird weighted random-effect pooled odds estimates for lifetime physical violence against a partner by women with diagnosed psychiatric disorders.

Discussion

This review highlights the lack of evidence on the recent perpetration of violence against a partner by men and women with psychiatric disorders. The majority of studies collected data on whether participants had ever perpetrated physical violence against a partner. Although reports of having ever been physically violent against a partner could include recent violence, these data do not allow assessment of current and or recent risk of violence towards a partner among people with psychiatric disorder.

A history of having perpetrated violence against a partner is one of the strongest risk factors for future violence (Stith et al. 2004). This review's finding that, across a range of diagnoses, men and women with psychiatric disorder have an increased risk of having ever been physically violent towards a partner may also indicate that there is an increased risk of current or future violence. The increase in risk was as high among those with CMD as those with SMI and the findings are consistent with a narrative review of risk factors for male-to-female partner abuse which reported higher prevalence of symptoms of psychotic and non-psychotic disorders among male abusers compared with non-abusers (Schumacher et al. 2001). The risk of violence perpetration was increased among both men and women with psychiatric disorders compared with those without a disorder, but more so for men than for women. This contrasts with the literature on violence victimization, where there is increased risk for both men and women with psychiatric disorder compared with those without a disorder, but more so for women than for men (Teplin et al. 2005; Khalifeh & Dean, 2010). However, for both men and women with psychiatric disorder, the increased risk of having ever been physically violent towards a partner is lower than the risk of having ever been a victim of partner violence (Trevillion et al. 2012; Jonas et al. 2013).

Previous reviews have demonstrated an increased risk of violence by people with psychiatric disorders but have not reported on who this violence was perpetrated against (Fazel et al. 2009, 2010). To our knowledge, this is the first review of the risk of violence to partners by people with psychiatric disorders. We used a comprehensive search strategy and followed MOOSE and PRISMA reporting guidelines (Stroup et al. 2000; Moher et al. 2009). We examined the prevalence and odds of violence across all psychiatric disorders, restricting the scope to studies that used validated diagnostic instruments, examining the prevalence and odds of violence perpetrated against a partner by men and women with psychiatric disorders, including both current and former partners; and extracting data from studies on psychiatric disorder and interpersonal violence. Between-study heterogeneity was acceptable.

Our review has several limitations. Although we found that men and women with psychiatric disorders are more likely to have a history of having been physically violent towards a partner compared with men and women with no psychiatric disorder, there is little data on whether this is the case during episodes of illness or is entirely explained by substance misuse. It is known that much of the increased risk of community violence among people with psychiatric disorders is related to substance misuse (Steadman et al. 1998; Appelbaum et al. 2000; Swanson et al. 2006; Elbogen & Johnson, 2009; Van Dorn et al. 2012); however, few primary studies collected data on substance abuse and we were not able to control for this potential confounder in the pooled analyses. In addition, controls used for the calculation of ORs included people with a primary diagnosis of substance misuse disorder, which may have inflated the prevalence of violence among controls and obscured the potential relationship between psychiatric disorder and violence towards a partner. It was also not possible to control for other potential confounders, such as prior violence (Walsh et al. 2004), pre-morbid conditions (Swanson et al. 2008a), psychiatric treatment (Swanson et al. 2008b) or other clinical and social factors that may increase the risk of violence (Soyka, 2000; Alhusen et al. 2010).

Owing to the limitations of the measures used in primary studies to assess the perpetration of physical violence against a partner, it was not possible to disentangle the perpetration of violence that occurred within the context of controlling behaviours (often seen as the defining features of ‘domestic violence’ or ‘intimate partner violence’), and which is more commonly perpetrated by men, from situational couple violence (Johnson, 1995; Johnson & Leone, 2005); impact was also not systematically reported in individual studies. Furthermore, the capacity of primary studies to differentiate between physical violence perpetration and victimization is likely to have been limited (Miller et al. 2011). Several studies used the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS) to measure violence (Straus, 1979), either in full or selected sub-scales, which has been criticized for its gender neutrality and for measuring acts out of context (i.e. not reporting whether acts of violence were in attack or defence), which may lead to differential misclassification bias across genders. Several papers reported modifying validated instruments without detailing how, if at all, the adapted measures were validated, or reported that they developed their own measures to assess violence. In addition, because the majority of studies measured only physical violence, we were unable to assess the relationship between psychiatric disorder and sexual and psychological violence.

Finally, we were unable to draw conclusions about whether a causal relationship exists between psychiatric disorder and the perpetration of violence against a partner. We sought to use data on past year rather than lifetime diagnoses of psychiatric disorder whenever possible, in order to avoid miscategorizing people as having psychiatric disorders on the basis of their psychiatric history rather than current symptomology (Van Dorn et al. 2012). However, the majority of primary studies measured physical violence towards a partner over the lifetime and not in the past year.

Further research is needed to address the evidence gaps identified by this review. In particular, high-quality longitudinal studies are needed to explore the nature of the association between psychiatric disorder and the perpetration of violence against partners. Studies should employ validated, multi-item scales to measure perpetration of violence against partners and should consider not only acts of physical, psychological and sexual violence but also their severity and frequency. Several large-scale psychiatric epidemiology surveys measure the perpetration of violence, but relatively few include questions about perpetrators' relationships to the victims of violence. However, the risk factors and consequences of violence against partners are likely to differ from those of violence against other acquaintances and strangers. Future psychiatric epidemiology surveys should include questions about the relationship between perpetrator and victim.

Conclusions

Further research is needed to investigate whether psychiatric disorders are associated with a current risk of violence to partners. Although men and women with psychiatric disorders have an increased risk of having ever been physically violent towards a partner, the risk of having ever been a victim of violence from a partner is more pronounced.

Acknowledgements

We thank the experts in this area who responded so helpfully to our request for data. We also gratefully acknowledge Estelle Malcolm for her assistance during spring 2012.

Financial support

L.M.H., S.O., K.T. and G.F. are supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Programme Grants for Applied Research scheme (RP-PG-0108-10084). L.M.H. is also supported by the NIHR Mental Health Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King's College London. This paper presents independent research funded by the NIHR under its Programme Grants for Applied Research scheme (RP-PG-0108-10084). The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. The sponsor of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Ethical standards

This review did not involve human or animal experimentation.

Conflict of Interest

L.M.H. and G.F. are members of the WHO Guideline Development Group on Policy and Practice Guidelines for responding to Violence Against Women and the NICE/SCIE Guideline Development Group on Preventing and Reducing Domestic Violence. S.O., H.K. and K.T. declare no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S2045796013000450.

click here to view supplementary material

References

- Alhusen JL, Lucea MB, Glass N (2010). Perceptions of and experience with system responses to female same-sex intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse 1, 443–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (1992). American medical association diagnostic and treatment guidelines on domestic violence. Archives of Family Medicine 1, 287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum PS, Robbins PC, Monahan J (2000). Violence and delusions: data from the MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study. American Journal of Psychiatry 157, 566–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalsbo TK, Johme T (2006). Cognitive behavioural therapy for men who physically abuse their female partner (Protocol). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielson KK, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Silva PA (1998). Comorbidity between abuse of an adult and DSM-III-R mental disorders: evidence from an epidemiological study. American Journal of Psychiatry 155, 131–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dersimonian R, Laird N (1986). Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Controlled Clinical Trials 7, 177–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downs SH, Black N (1998). The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 52, 377–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M, Davey SG, Schneider M, Minder C (1997). Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. British Medical Journal 315, 629–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbogen EB, Johnson SC (2009). The intricate link between violence and mental disorder: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry 66, 152–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazel S, Gulati G, Linsell L, Geddes JR, Grann M (2009). Schizophrenia and violence: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Medicine 6, e1000120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazel S, Lichtenstein P, Grann M, Goodwin GM, Langstrom N (2010). Bipolar disorder and violent crime: new evidence from population-based longitudinal studies and systematic review. Archives of General Psychiatry 67, 931–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood L, Ridder EM (2005). Partner violence and mental health outcomes in a New Zealand birth cohort. Journal of Marriage and Family 67, 1103–1119. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman S, Loue S, Goldman Heaphy E, Mendez N (2011). Intimate partner violence victimization and perpetration by puerto rican women with severe mental illnesses. Community Mental Health Journal 47, 156–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gass JD, Stein DJ, Williams DR, Seedat S (2011). Gender differences in risk for intimate partner violence among South African adults. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 26, 2764–2789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF & Kaplan KD (2005). Source and Accuracy Statement for the 2004–2005 wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism: Bethesda, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Harris RJ, Bradburn MJ, Deeks JJ, Harbord RM, Altman DG, Sterne JAC (2008). Metan: fixed- and random-effects meta-analysis. Stata Journal 8, 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Hiday VA, Swartz MS, Swanson JW, Borum R, Wagner HR (2002). Impact of outpatient commitment on victimization of people with severe mental illness. American Journal of Psychiatry 159, 1403–1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JPT, Thompson SG (2002). Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Statistics in Medicine 21, 1539–1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovens JG, Wiersma JE, Giltay EJ, Van Oppen P, Spinhoven P, Penninx BW, Zitman FG (2010). Childhood life events and childhood trauma in adult patients with depressive, anxiety and comorbid disorders vs. controls. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 122, 66–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MP (1995). Patriarchal terrorism and common couple violence: two forms of violence against women. Journal of Marriage and the Family 57, 283–294. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MP, Leone JM (2005). The differential effects of intimate terrorism and situational couple violence: findings from the national violence against women survey. Journal of Family Issues 26, 322–349. [Google Scholar]

- Jonas S, Khalifeh H, Bebbington PE, Mcmanus S, Brugha T, Meltzer H, Howard LM (2013). Gender differences in intimate partner violence and psychiatric disorders in England: results from the 2007 Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, FirstView, doi: 10.1017/S2045796013000292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Mcgonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen HU, Kendler KS (1994). Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry 51, 8–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE (2005). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62, 593–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalifeh H, Dean K (2010). Gender and violence against people with severe mental illness. International Review of Psychiatry 22, 535–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krug E, Mercy J, Dahlberg L, Ziwi A (2002). The World Report on violence and health. Lancet 360, 1083–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loney PL, Chambers LW (2000). Critical appraisal of the health research literature: prevalence or incidence of a health problem. Chronic Diseases in Canada 19, 170–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcmanus S, Meltzer H, Brugha S, Bebbington P, Jenkins R (2009). Adult Psychiatric Morbidity in England, 2007: Results of a Household Survey. National Centre for Social Research: London. [Google Scholar]

- Miller E, Breslau J, Petukhova M, Fayyad J, Green JG, Kola L, Seedat S, Stein DJ, Tsang A, Viana MC, Andrade LH, Demyttenaere K, De Girolamo G, Haro JM, Hu C, Karam EG, Kovess-Masfety V, Tomov T, Kessler RC (2011). Premarital mental disorders and physical violence in marriage: cross-national study of married couples. British Journal of Psychiatry 199, 330–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement. PLoS Medicine 6, e1000097. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najavits LM, Sonn J, Walsh M, Weiss RD (2004). Domestic violence in women with PTSD and substance abuse. Addictive Behaviors 29, 707–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICE (2008). The Guidelines Manual. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: London. [Google Scholar]

- O'leary KD, Tintle N, Bromet EJ, Gluzman SF (2008). Descriptive epidemiology of intimate partner aggression in Ukraine. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 43, 619–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrott DJ, Drobes DJ, Saladin ME, Coffey SF, Dansky BS (2003). Perpetration of partner violence: effects of cocaine and alcohol dependence and posttraumatic stress disorder. Addictive Behaviors 28, 1587–1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay J, Richardson J, Carter YH, Davidson LL & Feder G (2002). Should health professionals screen for domestic violence? Systematic review. British Medical Journal 325, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay J, Carter Y, Davidson L, Dunne D, Eldridge S, Feder G, Hegarty K, Rivas C, Taft A, Warburton A (2009). Advocacy interventions to reduce or eliminate violence and promote the physical and psychosocial well-being of women who experience intimate partner abuse. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, CD005043. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005043.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read J, Van Os J, Morrison A, Ross C (2005). Childhood trauma, psychosis and schizophrenia. A literature review with theoretical and clinical implications. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 112, 330–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg SD, Lu WL, Mueser KT, Jankowski MK, Cournos F (2007). Correlates of adverse childhood events among adults with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Psychiatric Services 58, 245–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha S, Chant D, Welham J, Mcgrath J (2005). A systematic review of the prevalence of schizophrenia. PLoS Medicine 2, 141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher JA, Feldbau-Kohn S, Smith Slep AM, Heyman RE (2001). Risk factors for male-to-female partner physical abuse. Aggression and Violent Behavior 6, 281–352. [Google Scholar]

- Sippel LM, Marshall AD (2011). Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, intimate partner violence perpetration, and the mediating role of shame processing bias. Journal of Anxiety Disorders 25, 903–910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soyka M (2000). Substance misuse, psychiatric disorder and violent and disturbed behaviour. British Journal of Psychiatry 176, 345–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statacorp (2009). Stata Statistical Software: Release 11. StataCorp: College Station, TX. [Google Scholar]

- Steadman HJ, Mulvey EP, Monahan J, Robbins PC, Appelbaum PS, Grisso T, Roth LH, Silver E (1998). Violence by people discharged from acute psychiatric inpatient facilities and by others in the same neighborhoods. Archives of General Psychiatry 55, 393–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterne JAC, Sutton AJ, Ioannidis JPA, Terrin N, Jones DR, Lau J, Carpenter J, Rücker G, Harbord RM, Schmid CH, Tetzlaff J, Deeks JJ, Peters J, Macaskill P, Schwarzer G, Duval S, Altman DG, Moher D, Higgins JPT (2011). Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. British Medical Journal, 343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stith SM, Smith DB, Penn CE, Ward DB, Tritt D (2004). Intimate partner physical abuse perpetration and victimization risk factors: a meta-analytic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior 10, 65–98. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA (1979). Measuring intra-family conflict and violence: the Conflict Tactics Scales. Journal of Marriage and the Family 41, 75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA, Thacker SB (2000). Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. Journal of American Medical Association 283, 2008–2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson J, Swartz M, Van Dorn R, Elbogen EB, Wagner R, Rosenheck R, Scott Stroup T, Mcevoy JP, Lieberman JA (2006). A national study of violent behavior in persons with schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry 63, 490–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson J, Van Dorn R, Swartz M, Smith A, Elbogen EB, Monahan J (2008a). Alternative pathways to violence in persons with schizophrenia: the role of childhood antisocial behaviour problems. Law and Human Behavior 32, 228–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson JW, Holzer CEI, Ganjur VK, Jono RT (1990). Violence and psychiatric disorder in the community: evidence from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area surveys. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41, 761–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson JW, Swartz MS, Essock SM, Osher FC, Wagner RH, Goodman LA, Rosenberg SD, Meador KG (2002). The social-environmental context of violent behavior in persons treated for severe mental illness. American Journal of Public Health 92, 1523–1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson JW, Swartz M, Van Dorn R, Volavka J, Monahan J, Stroup TS, Mcevoy JP, Wagner HR, Elbogen EB & Lieberman JA (2008b). Comparison of antipsychotic medication effects on reducing violence in people with schizophrenia. British Journal of Psychiatry 197, 37–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taft CT, Street AE, Marshall AD, Dowdall DJ, Riggs DS (2007). Posttraumatic stress disorder, anger, and partner abuse among Vietnam combat veterans. Journal of Family Psychology 21, 270–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taft CT, Weatherill RP, Woodward HE, Pinto LA, Watkins LE, Miller MW, Dekel R (2009). Intimate partner and general aggression perpetration among combat veterans presenting to a posttraumatic stress disorder clinic. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 79, 461–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taft C, Schwartz S, Liebschutz JM (2010). Intimate partner aggression perpetration in primary care chronic pain patients. Violence & Victims 25, 649–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teplin LA, Mcclelland GM, Abram KM, Weiner DA (2005). Crime victimization in adults with severe mental illness – Comparison with the national crime victimization survey. Archives of General Psychiatry 62, 911–921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trevillion K, Oram S, Feder G, Howard LM (2012). Experiences of domestic violence and mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 7, e51740. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dorn R, Volavka J, Johnson N (2012). Mental disorder and violence: is there a relationship beyond substance use? Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 47, 487–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh E, Buchanan A, Fahy T (2002). Violence and schizophrenia: examining the evidence. British Journal of Psychiatry 180, 490–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh E, Gilvarry C, Samele C, Harvey K, Manley C, Tattan T, Tyrer P, Creed F, Murray R, Fahy T (2004). Predicting violence in schizophrenia: a prospective study. Schizophrenia Research 67, 247–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wing JK (1994). The Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry. World Health Organization, Division of Mental Health: Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization & London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (2010). Preventing Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence against Women: Taking Action and Generating Evidence. World Health Organization: Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- Yang S, Mulvey EP, Loughran TA, Hanusa BH (2012). Psychiatric symptoms and alcohol use in community violence by persons with a psychotic disorder or depression. Psychiatric Services 63, 262–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S2045796013000450.

click here to view supplementary material