Abstract

Aims.

Previous population-based studies did not support the view that biological and genetic causal models help increase social acceptance of people with mental illness. However, practically all these studies used un-labelled vignettes depicting symptoms of the disorders of interest. Thus, in these studies the public's reactions to pathological behaviour had been assessed rather than reactions to psychiatric disorders that had explicitly been labelled as such. The question arises as to whether results would have been similar if respondents had been confronted with vignettes with explicit mention of the respective diagnosis.

Methods.

Analyses are based on data of a telephone survey in two German metropolises conducted in 2011. Case-vignettes with typical symptoms suggestive of depression or schizophrenia were presented to the respondents. After presentation of the vignette respondents were informed about the diagnosis.

Results.

We found a statistically significant association of the endorsement of brain disease as a cause with greater desire for social distance from persons with schizophrenia. In major depression, this relation was absent. With both disorders, there was no statistically significant association between the endorsement of hereditary factors as a cause and social distance.

Conclusions.

Irrespective of whether unlabelled or labelled vignettes are employed, the ascription to biological or genetic causes seems not to be associated with a reduction of the public's desire for social distance from people with schizophrenia or depression. Our results corroborate the notion that promulgating biological and genetic causal models may not help decrease the stigma surrounding these illnesses.

Key words: Causal attributions, major depression, schizophrenia, social distance

Introduction

In recent years, the relationship between biological or genetic (hereinafter referred to as ‘biogenetic’) explanations and attitudes towards people with mental disorders has received increasing interest. This was primarily motivated by the question whether promulgating biogenetic explanations may help reduce the stigma attached to mental illness and, therefore, should be included into anti-stigma messages (Clement et al. 2010). The expectation that biogenetic causal models of mental illness have de-stigmatising consequences rests on the assumption that attributing the cause of mental disorder to biogenetic factors will reduce ascriptions of responsibility and guilt to the afflicted persons, who, consequently, will experience less rejection by their social environment (Angermeyer et al. 2011).

A recently published systematic review of population-based studies (Angermeyer et al. 2011), however, did not provide support for this notion. As concerns schizophrenia, endorsement of brain disease was associated with greater social distance in three of four studies (Dietrich et al. 2004; Bag et al. 2006), attribution to genetic factors in five of seven studies (Dietrich et al. 2004; Bag et al. 2006; Kermode et al. 2009). The remaining studies did not yield statistically significant relationships (Dietrich et al. 2004; Grausgruber et al. 2007; Schnittker, 2008). Seeing depression as a consequence of a brain disease was associated with more social distance in two studies (Dietrich et al. 2004) while in one study no significant association was reported (Dietrich et al. 2004). Genetic attributions were associated with more social distance from people with depression in two studies (Dietrich et al. 2004), non-significant associations were found in another two studies (Dietrich et al. 2004; Kermode et al. 2009), and an association with less social distance in one study (Schnittker, 2008). In two studies with both disorders combined genetic attributions were unrelated to social distance (Phelan, 2005; Jorm & Griffiths, 2008). A recent population study in Germany not included in the review, that combined ‘brain disease’, ‘heredity’ and ‘chemical imbalance’ to a single measure of biogenetic causal explanations, showed that these were associated with more social distance in schizophrenia and depression (Schomerus et al. 2014). So far, the relationship between biogenetic attributions and social distance has only rarely been investigated with other disorders (alcoholism: Schnittker, 2008; Schomerus et al. 2013; eating disorders: Angermeyer et al. 2013). We therefore will focus in this paper on schizophrenia and depression.

Taking together the results summarised above one can say that, with one single exception, in all studies biogenetic beliefs were either associated with more social distance or showed no statistically significant relationship. Thus, they do not seem to support the view that biogenetic causal models help increase social acceptance of people with mental illness. However, there is one point worth notice. With the exception of one study (Phelan, 2005), all population-based studies used unlabelled vignettes depicting symptoms of the disorders of interest. This is to say that in these studies the public's reactions to pathological behaviour had been assessed rather than reactions to psychiatric disorders that had explicitly been labelled as such. Whether respondents had identified the symptoms described in the vignette as expression of the respective mental disorder or not remained unclear. Probably, informing respondents about the diagnosis of the condition described provides a medical framework in which potential benefits of biomedical conceptualisations are more tangible. In fact, in a survey conducted in Germany in 1990 it was found that respondents were more ready to ascribe symptoms of schizophrenia to a brain disease or to hereditary factors if the diagnosis was provided than if it was not provided (Angermeyer & Matschinger, 1996). Thus, the question arises as to whether results would have been similar if respondents had been confronted with vignettes with explicit mention of the respective diagnosis. This has, however, not been examined.

The present study complements the available evidence by examining the relation between causal beliefs of the public and reactions to a person with schizophrenia or depression using labelled vignettes, i.e., vignettes depicting a person suffering from either schizophrenia or major depression accompanied by the respective diagnosis. We want to know whether under this condition associations between biogenetic attributions and social distance resemble the ones previously observed in population studies employing unlabelled vignettes. Drawing on Corrigan & Watson's (2002) concept of public stigma we assumed that the association of biogenetic attributions with social distance is mediated through emotional reactions towards the afflicted person.

Method

Sample

Analyses are based on data of a telephone survey (computer-assisted telephone interviewing, CATI) in two German metropolises (Hamburg and Munich) conducted in 2011. Sample consists of adult individuals (18 years and older), living in private households with conventional telephone connection in one of the two metropolises. The sample was randomly drawn from all registered private telephone numbers, and additionally computer-generated numbers, allowing for ex-directory households as well. Repeat calls were made on eight occasions on different days of the week until a number dropped out. Informed consent was considered to have been given when individuals agreed to complete the interview. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Association in Hamburg. In total, 2014 individuals agreed to do the interview and participated in the study (1009 in Hamburg, 1005 in Munich). This reflects a response rate of about 51%. Comparisons with official statistics of the two cities show that except for a slight overrepresentation of younger respondents socio-demographic characteristics were similarly distributed in the sample and in the general population of Hamburg and Munich (Table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of socio-demographic characteristics in the study samples and in official statistics (Federal Statistical Office, 2012; Common Statistics Portal, 2012)

| Hamburg | Munich | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample (N = 1009, %) | Total population (%) | χ2 | Sample (N = 1005) (%) | Total population (%) | χ2 | |

| Gender | n.s. | n.s. | ||||

| Male | 48.4 | 48.9 | 48.9 | 48.5 | ||

| Female | 51.6 | 51.1 | 51.1 | 51.5 | ||

| Age | 0.008 | 0.001 | ||||

| 18–25 | 12.6 | 9.8 | 13.3 | 10.1 | ||

| 26–45 | 37.2 | 37.9 | 38.7 | 40.4 | ||

| 46–65 | 28.7 | 30.1 | 28.0 | 28.7 | ||

| > 65 | 21.6 | 22.2 | 20.0 | 20.8 | ||

| Education | n.s. | n.s. | ||||

| Low | 33.5 | 34.0 | 32.0 | 33.5 | ||

| Middle | 25.6 | 25.3 | 20.6 | 20.2 | ||

| High | 41.0 | 40.7 | 47.3 | 46.3 | ||

Vignettes

Written case-vignettes with typical signs and symptoms suggestive of depression, schizophrenia or eating disorders were presented to the respondents. All vignettes were developed with the input of clinicians based on the respective ICD-10 and DSM-IV criteria. In case of depression and schizophrenia, gender of the individual in the vignettes was systematically varied. All vignettes were audio-recorded with a trained speaker with clear voice. In order to increase reliability and to ‘neutralise’ possible interviewer-associated effects these audio files were presented to the interviewees directly from the computer via telephone line. After presentation of the vignette respondents were informed about the diagnosis. To reduce the length of the interview, only two vignettes were included in each interview. The vignettes were randomly permuted to eliminate order effects. Thus, each respondent answered questions concerning two disorders, resulting in about 1343 cases for each vignette (Knesebeck et al. 2013). In this paper, only results referring to the depression and schizophrenia vignette are presented.

Measures

Biogenetic explanations

Respondents were asked about possible causes of the mental disorders under study. Specifically, two items were used: (1) ‘A possible cause is a brain disease.’ (2) ‘A possible cause is heredity.’ They were coded from 1 (‘not at all correct’) to 4 (‘completely correct’).

Emotional reactions

According to previous research, three types of emotional reactions to people with mental illness can be distinguished: fear, anger and pro-social reactions (Angermeyer & Matschinger, 2003). A list of eight items, representing these three ways to respond to individuals with mental illness, was used to assess respondents' emotional reactions to the person described in the vignettes. With these items, which were coded from 1 (‘not at all correct’) to 4 (‘completely correct’), a factor analysis was carried out (principal component analysis with varimax rotation) which yielded the same three factors that have been found in previous studies (e.g., Angermeyer & Matschinger, 2003). The factors are termed ‘anger’ (items 1–3), ‘fear’ (items 4–5) and ‘pro-social reactions’ (items 6–8) (see Table 2). Together, they accounted for a cumulative variance of 60.5%.

Table 2.

Factor loading, eigenvalues and explained variances of principal component analysis with the eight items assessing emotional reactions (varimax rotation with Kaiser criterion). Factor loadings >.500 in bold

| Factor | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Eigenvalue = 2.34, explained variance = 29.3% |

2 Eigenvalue = 1.38, explained variance = 17.3% |

3 Eigenvalue = 1.11, explained variance = 13.9% |

||

| 1 | I react angrily | 0.823 | 0.070 | −0.006 |

| 2 | I feel annoyed by this person | 0.711 | 0.190 | −0.127 |

| 3 | This triggers incomprehension with me | 0.701 | 0.088 | −0.030 |

| 4 | This makes me feel uncomfortable | 0.226 | 0.768 | −0.211 |

| 5 | This induces fear with me | 0.201 | 0.741 | −0.136 |

| 6 | I feel pity | −0.097 | 0.609 | 0.485 |

| 7 | I feel the need to help this person | −0.076 | −0.038 | 0.779 |

| 8 | I feel sympathy | −0.024 | −0.151 | 0.742 |

Desire for social distance

Respondents' desire for social distance was assessed by means of a scale developed by Link et al. (1987). The scale includes seven items representing the following social relationships: tenant, co-worker, neighbour, person one would recommend for a job, person of the same social circle, in-law and child care provider. Using a four-point Likert scale (plus ‘do not know’ category), the respondents were asked to indicate to what extent they would, in the situation presented, accept or not accept the person described in the vignette. With the seven items a non-linear principal component analysis was carried out for each mental disorder under study. The first axis derived by this analysis was used as a measure for social distance. Higher scores indicate higher social distance. Internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha) amounted to 0.79 for depression and 0.85 for schizophrenia.

Statistical analysis

In order to examine the relationship between biogenetic causal beliefs, emotional reactions and desire for social distance path models were computed using Mplus, release 6.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 1989–2011). All variables were entered into the model simultaneously. Level of significance was set at p < 0.05, two-sided model fit was assessed using root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) by Browne & Cudeck (1993). The models were determined separately for individuals responding to the schizophrenia and major depression vignette, adjusted for the effect of gender and age.

Results

Distributions of the responses concerning biogenetic causes, emotional reactions and desire for social distance for depression and schizophrenia are shown in Table 3. Respondents confronted with the schizophrenia vignette expressed more fear and a greater desire for social distance. They also endorsed more frequently biogenetic causes than respondents confronted with the depression vignette. 20.9% of respondents presented with schizophrenia and almost nobody (0.4%) of those who had been presented with depression opted for biogenetic causes only (and not also for current psychosocial stress).

Table 3.

Distribution of biogenetic causes, emotional reactions and social distance

| Depression (N = 1342) | Schizophrenia (N = 1343) | |

|---|---|---|

| Possible causes (completely/rather correct, %) | ||

| Brain disease | 56.1 | 86.8 |

| Hereditary factors | 54.1 | 70.0 |

| Emotional reactions (mean, s.d.) | ||

| Fear | 1.64 (0.66) | 2.22 (0.86) |

| Anger | 1.56 (0.58) | 1.61 (0.58) |

| Pro-social | 3.00 (0.56) | 2.94 (0.59) |

| Social distance (mean, s.d.) | 15.42 (4.25) | 18.73 (4.84) |

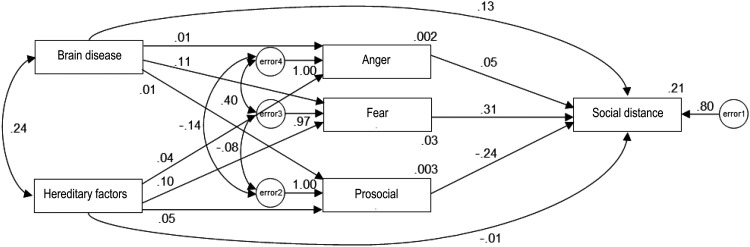

Figure 1 reports the path model for schizophrenia. The attribution to brain disease is associated with greater social distance, directly as well as indirectly through an increase of fear, which in turn is positively associated with social distance. There is also a path from hereditary factors to desire for social distance which is mediated by an increase of fear. While the total effect of brain disease on social distance is statistically significant (0.161, 95% CI 0.105; 0.218), this does not hold for the total effect of hereditary factors (0.011, 95% CI −0.046; 0.069).

Fig. 1.

Path model of the relationship between biogenetic attributions, emotional reactions and desire for social distance towards persons with schizophrenia. Standardised path coefficients; RMSEA: 0.012 (CI 0.000; 0.043); path coefficients <0.10 statistically not significant.

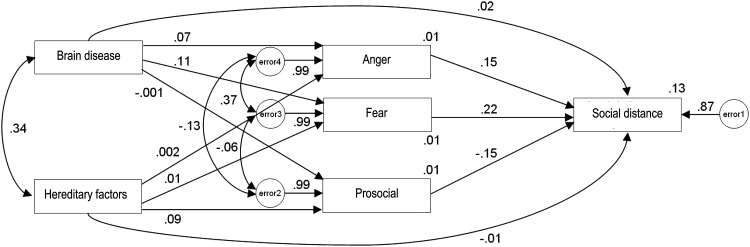

As shown in Fig. 2, reporting the path model for major depression, the endorsement of brain disease is linked with stronger expression of anger and fear, which both are related to an increase in social distance. Hereditary factors, in contrast, are positively associated with pro-social feelings, which in turn relate negatively to social distance. The total effect of brain disease and hereditary factors on social distance is not statistically significant (0.056, 95% CI −0.004; 0.116, and −0.022, 95% CI −0.082; 0.038, respectively).

Fig. 2.

Path model of the relationship between biogenetic attributions, emotional reactions and desire for social distance towards persons with major depressive disorder. Standardised path coefficients; RMSEA: 0.012 (CI 0.000; 0.034); path coefficients <0.07 statistically not significant.

Discussion

In summary, we found a statistically significant association between the endorsement of brain disease as a cause and greater desire for social distance from persons with schizophrenia. In major depression, there was no significant relationship. With both disorders, there was no statistically significant association between the endorsement of hereditary factors as a cause and social distance. By and large, our results are in line with what had been observed in previous studies (Angermeyer et al. 2011; Schomerus et al. 2014): Biogenetic explanations and social distance either are unrelated or the first are associated with an increase of the latter. This congruence suggests that it matters little whether an unlabelled or a labelled vignette is used when examining the relationship between biogenetic causes and social distance. Also when the psychiatric diagnosis is made explicit, biogenetic causal explanations seem not to show the expected beneficial effect on people's attitudes.

Our findings indicate that fear evoked by the attribution to brain disease seems to play an important role, particularly as concerns the desire for social distance from people with schizophrenia. This is congruent with findings from a national survey conducted in Germany in 2001 in which unlabelled vignettes had been used. Here too, the endorsement of brain disease was linked to an increase in fear, resulting in greater social distance from a person with schizophrenia (Dietrich et al. 2006). Thus, similar reactions seem to be evoked by the ascription to brain disease, no matter whether respondents have been presented with the plain depiction of schizophrenic behaviour or with the label ‘schizophrenia’ in conjunction with symptoms.

In schizophrenia, the endorsement of hereditary factors seems to be associated with more fear (and to be unrelated to pro-social feelings) while in depression it is positively associated with pro-social feelings. However, in both cases the total effect of hereditary factors on social distance does not reach statistical significance. This is congruent with the only population study in which also labelled vignettes had been used, showing no association between the endorsement of a genetic cause and the desire for social distance from people with schizophrenia and depression combined (Phelan, 2005).

While in case of schizophrenia the attribution to a brain disease was associated only with fear, with depression there was an additional link to anger. A pattern similar to the latter had also been observed with eating disorders (Angermeyer et al. 2013). Variations of emotional reactions across diagnoses have also been found regarding the attribution to hereditary factors: In case of schizophrenia (as well as anorexia nervosa, see Angermeyer et al. 2013) they were associated with more fear, in case of depression with more pro-social reactions, and in case of bulimia nervosa there was no association with any emotion (Angermeyer et al. 2013). Thus, biogenetic attributions seem not necessarily evoke the same reactions across different diagnoses (Rüsch et al. 2012).

The finding that endorsement of brain disease was linked with stronger expression of anger in depression but not in schizophrenia may also have to do with the fact that, while a great majority of respondents agreed that schizophrenia is a brain disease, the public was more equivocal about depression. This may, in consequence, have resulted in the group that agreed that depression is a brain disease representing a somewhat more extreme subset of the group that agreed that schizophrenia is a brain disease.

The results have to be seen in the light of the limitations of our study. First, the response rate did not exceed 51%, which raises the question of representativeness of our findings. Unfortunately, no data are available on non-responders that would allow us to assess their similarities and differences from responders. All we can say is that with regard to major socio-demographic characteristics, our sample is comparable to the total population (see Table 1). Second, respondents were contacted only via landline which may also raise the question of representativeness as in recent studies in Australia differences in socio-demographic characteristics between landline and mobile-only respondents have been observed (Holborn et al. 2012). However, as mentioned above, our sample reflects quite well the socio-demographic composition of the two metropolises under study. We therefore assume that this may not have biased our results to a significant extent. Third, we do not know to what extent the items used in our study (‘brain disease’, ‘hereditary factors’) really capture the public's conceptualisation of the biogenetic aetiology of mental disorders. However, an explanatory factor analysis with the complete list of potential causes that had been presented to respondents yielded, apart from factors representing current stress, childhood adversities, and personality factors, one factor including these two items, suggesting that they in fact represent a distinct ‘biogenetic’ dimension (Angermeyer et al. 2013). Fourth, the use of the descriptor ‘brain disease’ has been considered as problematic in view of the fact that many public education material use terms like ‘biochemical imbalance in the brain’. It has been argued that at least for depression, the connotations of brain disease may be quite different from that of biochemical imbalance (Griffiths & Christensen, 2004). However, in a national survey conducted in Germany in 2011, we were able to show that both attributions are highly correlated with each other and that both are related to greater desire for social distance from both people with schizophrenia and with major depression (Speeforck et al. unpublished results). Fifth, with an explained variance of 21% (schizophrenia) and 13% (major depression), the explanatory power of our models is rather limited. Lastly, our results originate from two German cities. Before generalising them, replication with other populations is necessary.

In conclusion, we can state that biogenetic explanations seem to have a similar effect on people's desire for social distance from persons with schizophrenia and depression, irrespective of whether unlabelled or labelled vignettes have been employed. In both cases, the ascription to biogenetic causes has not been found to be associated with a reduction of the public's desire for social distance. Our results corroborate the notion that promulgating biogenetic causal models may not help decrease the stigma surrounding these two mental illnesses (e.g., Hengartner et al., 2013; Lasalvia & Tansella, 2013). As concerns schizophrenia, it may even entail the risk of increasing it.

Other strategies such as facilitating contact with mentally ill persons (Angermeyer & Dietrich, 2006) or promulgating the notion of a continuum between normality and mental illness (Schomerus et al. 2013) seem more useful.

Financial Support

The study is supported by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (01KQ1002B) in the frame of ‘psychenet – Hamburg network mental health’ (2011–2014). Psychenet is part of the national programme in which the City of Hamburg was given the title ‘Health Region of the Future’ in 2010 (see also www.psychnet.de).

Ethical Standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- Angermeyer MC, Dietrich S (2006). Public beliefs about and attitudes towards people with mental illness: a review of population studies. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 113, 163–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H (1996). The effect of diagnostic labelling on the lay theory regarding schizophrenic disorders. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 31, 316–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H (2003). The stigma of mental illness: effects of labeling on public attitudes towards people with mental disorder. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 108, 303–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angermeyer MC, Holzinger A, Carta MG, Schomerus G (2011). Biogenetic explanations and public acceptance of mental illness. A systematic review of population studies. British Journal of Psychiatry 199, 367–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angermeyer MC, Mnich E, Daubmann A, Wegscheider K, Kofahl C, Knesebeck Ovd (2013). Biogenetic explanations and public acceptance of people with eating disorders: results from population surveys in two large German cities. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 48, 1667–1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bag B, Yilmaz S, Kirpinar I (2006). Factors influencing social distance from people with schizophrenia. International Journal of Clinical Practice 60, 289–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit Testing Structural Equation Models (ed. Bollen KA and Long JS), pp. 136–162. Sage Publications: New Park. [Google Scholar]

- Clement S, Jarrett M, Henderson C, Thornicroft G (2010). Messages to use in population-level campaigns to reduce mental health-related stigma: consensus development study. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences 19, 72–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Common Statistics Portal (2012). Retrieved 25 March 2014 from http://www.statistikportal.de.

- Corrigan PW, Watson AC (2002). Understanding the impact of stigma on people with mental illness. World Psychiatry 1, 6–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich S, Beck M, Bujantugs B, Kenzine D, Matschinger H, Angermeyer MC (2004). The relationship between public causal beliefs and social distance toward mentally ill people. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 38, 348–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich S, Matschinger H, Angermeyer MC (2006). The relationship between biogenetic causal explanations and social distance toward people with mental disorders: results from a population survey in Germany. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 52, 166–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federal Statistical Office (2012). Retrieved 25 March 2014 from https://www.destatis.de.

- Grausgruber A, Meise U, Katschnig H, Schöny W, Fleischhacker WW (2007). Patterns of social distance towards people suffering from schizophrenia in Austria: a comparison between the general public, relatives and mental health staff. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 115, 310–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths KM, Christensen H (2004). Commentary on ‘The relationship between public causal beliefs and social distance toward mentally ill people’. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 38, 355–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hengartner MP, Loch AA, Lawson FL, Guarniero FB, Wang Y-P, Rössler W, Gattau WF (2013). Public stigmatization of different mental disorders: a comprehensive attitude survey. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences 22, 269–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holborn AT, Reavley NJ, Jorm AF (2012). Differences between landline and mobile-only respondents in a dual-frame mental health literacy survey. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 36, 192–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorm AF, Griffiths KM (2008). The public's stigmatizing attitudes towards people with mental disorders: how important are biomedical conceptualizations? Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 118, 315–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kermode M, Bowen K, Arole S, Pathare S, Jorm AF (2009). Attitudes to people with mental disorders: a mental health literacy survey in a rural area of Maharashtra, India. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 44, 1087–1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knesebeck Ovd, Mnich E, Kofahl C, Makowski AC, Lambert M, Karow A, Bock T, Härter M, Angermeyer MC (2013). Estimated prevalence of mental disorders and the desire for social distance: results from population surveys in two large German cities. Psychiatry Research 209, 670–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasalvia A, Tansella M (2013). What is in a name? Renaming schizophrenia as a starting point for moving ahead with its re-conceptualization. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences 22, 285–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Cullen FT, Frank J, Wozniak JF (1987). The social rejection of former mental patients: understanding why labels matter. American Journal of Sociology 92, 1461–1500. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO (1998. –2011). Mplus User's Guide, 6th edn. Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Phelan JC (2005). Geneticization of deviant behavior and consequences for stigma: the case of mental illness. Journal of Health and Social Behaviour 46, 307–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüsch N, Evans-Lacko S, Thornicroft G (2012). What is a mental illness? Public views and their effects on attitudes and disclosure. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 46, 641–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnittker J (2008). An uncertain revolution: why the rise of a genetic model of mental illness has not increased tolerance. Social Science and Medicine 67, 1370–1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schomerus G, Matschinger H, Angermeyer MC (2013). Continuum beliefs and stigmatizing attitudes towards persons with schizophrenia, depression and alcohol dependence. Psychiatry Research 209, 665–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schomerus G, Matschinger H, Angermeyer MC (2014). Causal beliefs of the public and social acceptance of persons with mental illness: a comparative analysis of schizophrenia, depression and alcohol dependence. Psychological Medicine 44, 303–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]