Abstract

The past two decades have witnessed a paradigm shift in the management of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), particularly with the introduction of targeted therapies to clinical practice. Ibrutinib is an irreversible inhibitor of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) and has shown significant efficacy and tolerability, even in heavily treated patients. Despite improvement in outcomes, patients do ultimately relapse. Those who develop disease progression on ibrutinib are a particularly high-risk population with poor outcomes. Identifying patients at higher risk of relapse while on therapy is needed for individualized clinical monitoring and timely subsequent management upon relapse. In this article, we discuss characteristics of CLL progression, risk factors for relapse on ibrutinib including clinical and molecular biomarkers, and a risk-adapted approach to identifying, monitoring, and managing CLL patients during ibrutinib therapy.

Keywords: CLL, ibrutinib, relapse, high-risk, BTK & PLCG2 mutations

Introduction

The past two decades have witnessed significant improvement in the outcomes of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). The introduction of chemoimmunotherapy (such as fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab [FCR]) has resulted in superior overall response rates (ORR), progression-free survival (PFS), and overall survival (OS) compared to combination of fludarabine and cyclophosphamide [1–5]. Although a subset of patients are able to sustain long-lasting remissions (particularly those with mutated immunoglobulin heavy chain (IGHV) genes) [6,7], most patients relapse; and until recently treatment options for relapsed disease were quite limited. Over the past few years, the development of novel, targeted agents dramatically changed the CLL management landscape. Ibrutinib, an orally available inhibitor of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK), is the first such agent to be approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Agency (EMA), and it currently has approval in the frontline and relapsed/refractory settings.

Despite encouraging data and improved outcomes with ibrutinib, patients do ultimately relapse. This is particularly true in previously treated patients – a population known to have a shorter duration of response on ibrutinib compared with treatment-naïve patients [8]. Disease progression on ibrutinib poses a significant challenge and unmet need since patients tend to do poorly, with survival in the order of months according to data from multiple groups [9–11]. Identifying CLL patients on ibrutinib who are at high risk of relapse can help tailor monitoring to adequately assess disease evolution and plan treatment strategies in advance to address disease progression when it occurs. In this review, we will highlight the clinical efficacy of ibrutinib in CLL, discuss the nature of and risk factors for CLL disease progression on ibrutinib, explore strategies to identify and monitor high-risk patients, and briefly address subsequent management following relapse.

Ibrutinib in CLL

Ibrutinib is an irreversible inhibitor of BTK, a component of the B-cell receptor (BCR) signaling pathway. Aberrant activation of BCR signaling in CLL promotes abnormal B-cell proliferation and survival, thus rendering this pathway an attractive target for novel therapies such as ibrutinib. The antitumor activity of this drug stems from interference with BCR signaling and interruption of adhesion and migration pathways [12–14].

The efficacy of ibrutinib was first demonstrated in relapsed CLL in a phase 1b/2 study where 85 previously treated patients with mostly high-risk disease received ibrutinib at a dose of 420 mg (n = 51) or 840 mg (n = 34) daily. At a median follow-up of 30 months, PFS was 69% and OS was 79%. It is worth noting that the study population was heavily treated (median number of prior lines of therapy was 4) and patients with high-risk cytogenetics were included, such as del17p13 in 33% and del11q23 in 36% of patients [8,15]. A rather interesting observation was the frequent initial rise in lymphocyte count followed by a persistent lymphocytosis despite improvement in other clinical parameters such as neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and adenopathy [15]. This phenomenon was described before in agents targeting the BCR pathway, which prompted updates for the response assessment criteria [16]. In a subsequent pivotal phase 3 clinical trial, ibrutinib was compared with the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody ofatumumab (RESONATE study). At a median follow-up of 9.4 months, PFS was significantly higher in the ibrutinib arm – not reached versus 8.1 months (hazard ratio for progression or death in the ibrutinib arm, 0.22; p < .001). Overall survival estimates at 12 months were 90% for ibrutinib and 81% for ofatumumab (hazard ratio for death in the ibrutinib arm, 0.43; p = .005) [17]. An updated analysis revealed continued ibrutinib efficacy in all prognostic subgroups at a median follow-up of 19 months. The median PFS in the ibrutinib arm was not reached and 74% of these patients were alive and progression-free at 24 months [18].

Ibrutinib has been evaluated in the frontline setting as well, with the longest follow-up from the treatment-naïve arm of the phase 1b/2 trial mentioned earlier, which comprised a total of 31 symptomatic, previously untreated patients. The 3-year analysis (median follow-up of 35.2 months) showed that median PFS was not reached and PFS at 30 months was 96% (one patient developed histologic transformation) [8]. The most updated data is from a 5-year analysis with a median follow-up of 60 months for treatment-naïve patients, in whom ORR was 84% and median PFS was not reached [19]. The phase 3 trial examining frontline ibrutinib in treatment-naïve CLL compared it with single-agent chlorambucil (RESONATE-2 study) and demonstrated improvement in both median PFS (not reached versus 18.9 months) and OS (estimated OS at 24 months of 98% versus 85%). The overall response rate (ORR) was also higher in the ibrutinib arm (86% versus 35%, p < .001) [20].

Ibrutinib was also found to be effective in patients with del17p13/TP53 aberrations, a population known to be quite resistant to traditional cytotoxic treatments and chemoimmunotherapy. A phase 2 clinical trial studied ibrutinib in patients with relapsed CLL and del17p13 (RESONATE-17 study). The ORR after a median follow-up of 27.6 months was 83% and 24month PFS and OS were 63 and 75%, respectively [21]. Another phase 2 study evaluated ibrutinib in both treatment-naïve and relapsed CLL patients with TP53 disruption. This too showed encouraging results with an ORR of 97% in treatment-naïve and 80% in relapsed patients. Estimated OS at 24 months was 84% for previously untreated patients and 74% for those with relapsed disease [22].

Collectively, these data indicate that ibrutinib as a single-agent is extremely effective in the treatment of CLL patients – in both frontline and relapsed settings – and also among patients who are traditionally considered to have poor outcomes, including those with del17p13/TP53 mutation and unmutated IGHV (Table 1). The safety of ibrutinib has been established in multiple clinical trials. Fatigue, nausea, diarrhea, and fever were among the most common non-hematologic adverse events noted in the ibrutinib arm of the RESONATE study, and occurred in at least 20% of patients. Grade 3 or higher adverse events that were reported more frequently with ibrutinib were diarrhea and atrial fibrillation. Furthermore, adverse events of any grade that occurred more frequently in ibrutinib-treated patients compared with those treated with ofatumumab were bleeding, rash, pyrexia, infections, and blurred vision [17]. Despite these adverse events, the vast majority of patients are able to continue with ibrutinib therapy and derive significant benefit from ongoing use.

Table 1.

Summary of key ibrutinib trials in chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

| Trial name |

Phase |

Treatment setting |

Study regimen |

N |

Median follow-up |

ORR |

CR |

PFS |

Major AEs grade 3 or higher |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Targeting BTK in CLL (PCYC-1102 and PCYC-1103) | 1 b/2 | Treatment-naive and previously treated | Ibrutinib (420 and 840 mg) | 31 treatment-naive and 101 previously treated | 46 months (60 for TN and 39 for PT) |

86% for all (84% for TN and 86% for PT) | 14% for all (29% for TN and 10% for PT) | Not reached for TN and 52 months for PT | Hypertension, pneumonia, neutropenia, atrial fibrillation | [8,15,19] |

| RESONATE | 3 | Previously treated | Ibrutinib 420 mg versus ofatumumab | 195 ibrutinib and 196 ofatumumab | 19 months | 90% versus 25% | 7% versus 0.5% | NR versus 8.1 months | Neutropenia, pneumonia, anemia, thrombocytopenia | [17,18] |

| RESONATE-2 | 3 | Treatment-naive | Ibrutinib 420 mg versus chlorambucil | 136 ibrutinib and Ί33 chlorambucil | 18.4 months | 86% versus 35% | 4% versus 2% | NR versus 18.9 months | Neutropenia, anemia, hypertension, pneumonia, diarrhea | [20] |

| RESONATE-17 | 2 | Previously treated, del 17p | Ibrutinib 420 mg | 144 | 27.6 months | 83% | 8% | NR | Neutropenia, pneumonia, hypertension, anemia, atrial fibrillation, thrombocytopenia | [21] |

TN: treatment-naive; PT: previously treated; ORR: overall response rate; CR: complete response; PFS: progression-free survival; NR: not reached; AE: adverse event.

Characteristics of disease relapse on ibrutinib

Relapsed disease on ibrutinib therapy can take the form of progressive CLL or, less commonly, histologic transformation to aggressive lymphoma (also known as Richter’s transformation of CLL). Ascertaining true disease progression and relapse can be quite challenging as patients on ibrutinib tend to have persistent lymphocytosis and do not usually achieve complete remission (CR) [23,24]. Repeat assessment and utilization of imaging and other testing may be needed to define progressive disease. Distinguishing relapsed disease from other causes of ibrutinib discontinuation, such as intolerance or toxicity, is important. Patients who stop ibrutinib for reasons other than disease progression have a different disease tempo and may do well with other therapies. In a report by Mato et al., 143 patients who discontinued ibrutinib therapy were analyzed. Of those, 73 stopped therapy due to toxicity while 51 discontinued treatment due to CLL progression or Richter’s transformation of CLL. With a median follow-up of 14 months, median PFS was 7 months in the patients with disease progression and was not reached in the group that stopped therapy due to toxicity [25].

Patterns of disease relapse (namely, CLL progression and Richter’s transformation of CLL) vary with regards to onset from initiation of ibrutinib, rapidity of disease progression, and cytogenetic and molecular alterations (Table 2). A significant proportion of patients do relapse within a few years of initiating treatment. Woyach et al. reported an estimated cumulative incidence of CLL progression and transformation at 4 years of 19 and 9.6%, respectively, in an analysis of 308 patients treated with ibrutinib [26]. Disease relapse due to CLL progression tends to occur later in the course of ibrutinib therapy compared to relapse due to Richter’s transformation of CLL. Indeed, in this same study by Woyach et al., the estimated cumulative incidence of CLL progression increased from 0.7% at 1 year to 19.1% at 4 years, while the estimated cumulative incidence of transformation did not increase significantly beyond 2 years. Other studies have shown a similar trend of increasing incidence of CLL progression (from initiation of ibrutinib therapy) over time. Ahn et al. reported on 84 patients enrolled in a phase 2 trial treated with single-agent ibrutinib and noted progression due to CLL in 11.9% of patients, diagnosed at a median of 38 months on study [27]. As noted above, Richter’s transformation of CLL tends to occur earlier in the course of ibrutinib therapy and is associated with a more aggressive disease course. Histologic transformation could be either clonally related or unrelated to the CLL clone [27]. Historically, the risk of Richter’s transformation in patients treated with chemoimmunotherapy has been reported to be 1–2% per year [28]. Although the cumulative incidence of Richter’s transformation at 12 and 18 months of 4.5 and 6.5%, respectively, is higher in ibrutinib-treated patients [10], we cannot directly attribute this risk to ibrutinib, since the vast majority of these patients have very high risk disease and have received multiple prior lines of therapy.

Table 2.

Characteristics of disease relapse on ibrutinib in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

| CLL progression | Richter’s transformation of CLL | |

|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | Constitutional symptoms, worsening cytopenias, enlarging lymph nodes, organomegaly | Rapid-onset constitutional symptoms, sudden worsening of lymphadenopathy, organomegaly |

| Onset from ibrutinib initiation | Usually beyond 12 months | Usually within 12 months |

| Histologic features | Progressive CLL without histologic transformation | Histologic transformation, usually DLBCL |

| Cytogenetic and molecular lesions | BTK and PLCG2 mutations, clonal evolution, subclones harboring del(8p), del(18p), EP300, MLL2, and EIF2A mutations [26,30,34] | Complex karyotype, TP53 disruption, NOTCH1 mutation, c-MYC abnormalities, SF3B1 mutation [26,62] |

There is currently better understanding of the mechanisms underlying CLL relapse on ibrutinib, and these are closely tied to the development of acquired resistance to the drug. Ibrutinib exerts its action by covalently binding to the BTK enzyme at the C481 residue [26,29]. Acquired BTK mutations affecting this binding site have been established as a source of ibrutinib resistance, most notably the BTK C481S alteration. This impacts the ability of ibrutinib to bind to BTK and renders it a reversible inhibitor [26,30,31]. Apart from BTK, mutations affecting PLCG2 have also been implicated in the development of resistance. PLCG2 is a signaling protein that is downstream of BTK in the BCR pathway. Gain-of-function mutations affecting the autoinhibitory domain of PLCG2 (thus leading to activation of phospholipase Cγ 2 enzymatic activity) have been described, such as the R665W and L845F mutations [31,32]. It is worth noting that the majority (80–85%) of patients relapsing on ibrutinib develop BTK and/or PLCG2 mutations. Multiple subclones harboring such mutations can be detected many months before the onset of clinical progression [26,27]. In the study by Woyach et al. [26], eight patients were identified on follow-up who had increasing circulating CLL cells and expanding resistant clones. Four of these patients had enlarging lymph nodes on imaging, but none of the eight patients met criteria for clinical relapse. Interestingly, such mutations were previously not felt to be present at baseline prior to initiation of ibrutinib therapy [33]. More recent data from whole-exome and deep-targeted sequencing and using mathematical modeling have inferred that ibrutinib-resistant subclones may be present prior to initiation of treatment (although no such clones have been conclusively demonstrated from patient samples prior to ibrutinib start) [30].

Apart from BTK and PLCG2 mutations, alterations involving the short arm of chromosome 8 have also been reported to confer resistance leading to disease relapse. Subclones harboring del8p have been noted to expand under therapeutic pressure and shown to possess driver mutations involving various genes (EP300, MLL2, and EIF2A). Such clones develop resistance to apoptosis and enhanced survival and growth rates [30]. In a recent study examining clonal evolution in CLL relapse on ibrutinib, del18p was noted to be frequently present prior to initiation of ibrutinib treatment and was felt to cooperate with del17p13/TP53 mutations to promote refractoriness to prior lines of therapy [34].

Conversely, as Richter’s transformation of CLL tends to happen earlier in the course of ibrutinib treatment, it is more likely to be related to molecular alterations present prior to ibrutinib initiation. Most notably, del17p13/TP53 aberrations (a recognized risk factor for histologic transformation) were shown to frequently predate ibrutinib therapy [34].

Risk factors for progression on ibrutinib

A number of clinical, cytogenetic, and molecular biomarkers have been reported to be associated with inferior outcomes in higher-risk CLL, and most of these have been described in the pre-ibrutinib era [35]. More data is becoming available regarding risk factors for progression during ibrutinib therapy, and it is likely that additional prognostic factors will be identified with longer clinical follow-up [36].

One predictor of disease relapse and inferior outcomes in ibrutinib-treated patients is the presence of complex cytogenetics. The latter is defined as the presence of 3 or more distinct chromosomal alterations and has been found to be highly associated with 17p aberrations [37]. The prognostic nature of a complex karyotype in ibrutinib-treated patients was verified by Thompson et al. in a study of 88 patients treated for relapsed CLL with investigational ibrutinib-based regimens [38]. Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) and lipopolysaccharide-stimulated metaphase cytogenetic analysis were performed on pretreatment bone marrow samples. In multivariate analysis, complex metaphase karyotype and fludarabine-refractory CLL were significantly associated with shorter event-free survival (EFS), while only complex karyotype was significantly associated with inferior OS. Interestingly, del17p13 by FISH was not significantly associated with either EFS or OS in multivariate analysis in this study.

Other biomarkers have also been associated with disease progression in ibrutinib-treated patients. Maddocks et al. determined that del17p13 and number of prior lines of therapy are risk factors in univariate (but not multivariate analysis) [10]. In contrast, Ahn et al. identified relapsed disease, advanced Rai stage (III/IV), and TP53 aberrations as independent risk factors in multivariate analysis, after adjusting for age and IGHV mutation status [27]. In another analysis by Woyach et al., del17p13 and younger age (in addition to complex karyotype) were found to be independent risk factors for progressive CLL [26]. In this same study, only complex karyotype was shown to be an independent predictor of Richter’s transformation of CLL, although there was a trend toward significance for the variable of MYC abnormalities in multivariable analysis.

One can glean from the above that there is lack of consistency among studies with regards to the predictive value of various biomarkers, particularly complex karyotype and del17p13. This issue is further compounded by the fact that in the vast majority of patients who have complex karyotype, del17p13 coexists, and the relative contribution of complex karyotype over and above del17p13 alone is difficult to dissect, which at the present time limits our ability to make solid conclusions. The arena of risk factors and predictive biomarkers in the ibrutinib-treated CLL population is evolving rapidly. The value of historical biomarkers in this era of novel, targeted therapies remains unclear [39]. Identification and verification of prognostic factors is likely to occur in the near future as more data continues to emerge from clinical trial follow-up.

Approach to identifying and following high-risk patients

Identification of high-risk CLL patients, particularly prior to and during CLL therapy, can help individualize testing, monitoring, and planning for future therapies.

If a patient is being considered for initiation of ibrutinib therapy, a full staging and risk assessment workup is undertaken. This workup generally includes a complete blood count with differential (CBC), chemistries, beta-2 microglobulin level, direct antiglobulin test, hepatitis B and C screening, flow cytometry, dedicated CLL FISH panel (which looks for recurrent alterations detectable by FISH), bone marrow aspirate and biopsy, CpG oligonucleotide stimulated karyotype (CpG stimulation has been shown to produce more consistent results and lead to enhanced detection of abnormalities [40,41]), computed tomographic (CT) imaging, IGHV mutation status, and TP53 sequencing. Due to significant drug-drug interactions and potential for increased toxicity, all patients should undergo evaluation by pharmacy prior to starting therapy to assess whether adjustments to home medications or ibrutinib dose are needed [42]. For patients who have high-risk disease (defined as the presence of del17p13, del11q23, or complex cytogenetics), we refer them to a transplant specialist, if not already done previously.

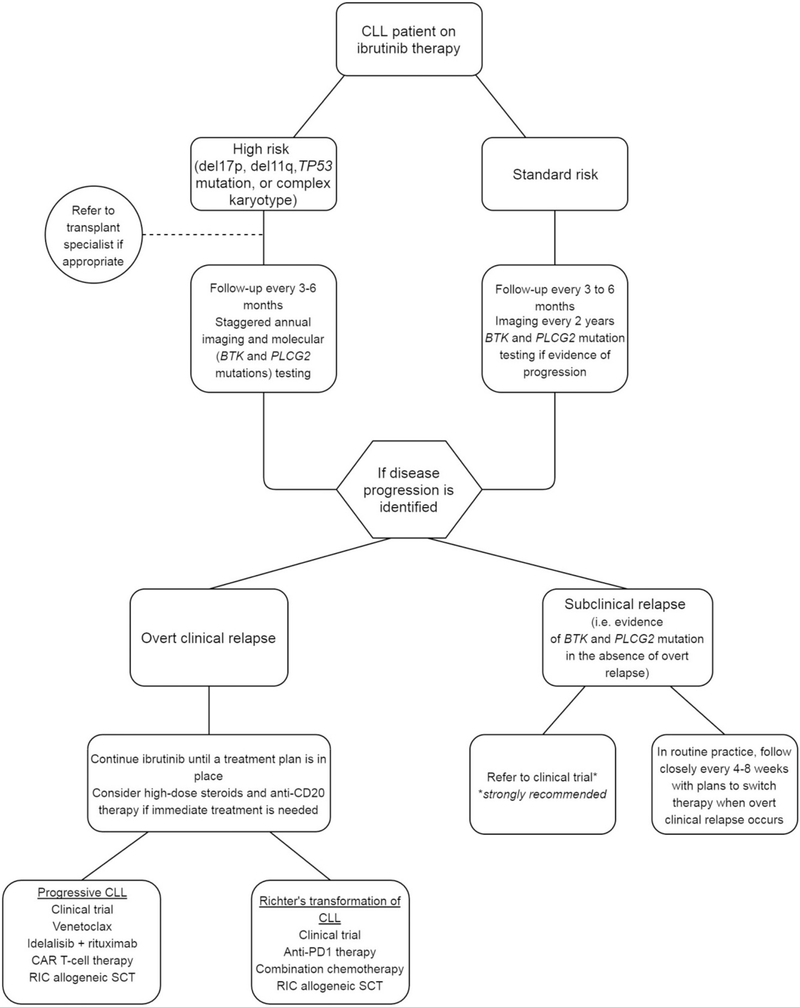

With regards to follow-up, we individualize the frequency of monitoring and testing based on patient and disease characteristics and risk assessment (Figure 1). Testing for BTK and PLCG2 mutations is currently not available in routine clinical laboratories. Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) certified reference laboratories where samples may be sent for testing include Ohio State University (http://pathology.osu.edu/ext/divisions/Clinical/molpath/tests.html) and NeoGenomics (https://neogenomics.com/test-menu/btk-mutation-analysis; https://neogenomics.com/test-menu/plc-gamma-2-mutation-analysis). The turn-around time for these tests is approximately 2–3 weeks, and testing may cost around US$1000–2000 (which may or may not be reimbursed by the patient’s medical insurance in routine clinical practice). Given the expense of testing for acquired mutations in BTK and PLCG2 genes and the fact that these costs may not be covered by the patient’s medical insurance, we favor a tailored approach to monitor for the emergence of these mutations based on the patient’s CLL risk profile. We classify patients as high-risk based on the presence of at least one of the following: complex cytogenetics, del17p13, TP53 mutation, or del11q23. In addition to a routine clinic visit every 3–6 months with close monitoring for symptoms and signs of progression, high-risk patients undergo imaging (CT) and molecular (detection of BTK and PLCG2 mutations) studies once every year (testing is staggered such that patients get either of these tests done once every 6 months) to identify asymptomatic progression of disease or emergence of resistant subclones.

Figure 1.

Suggested approach to clinical monitoring during ibrutinib therapy and management upon disease progression in patients with CLL. CAR T-cell: chimeric antigen receptor T-cell; RIC: reduced intensity conditioning; SCT: stem cell transplant; PD1: programed death 1; CLL: chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

While detection of BTK and/or PLCG2 mutations in patients without overt clinical signs of progression may not immediately change management, these patients need to be closely monitored and considered for enrollment in well-planned clinical trials. Based on current standard of care and available evidence, detection of such mutations in patients without clinical progression should not change management outside of a clinical trial setting.

For patients in the standard risk category (del13q, trisomy 12, and negative FISH), we follow them in the clinic every 3–6 months and with radiographic imaging studies once every 2 years. We perform mutation studies in these patients only if there is evidence of asymptomatic or overt progression of disease. Based on the extremely favorable outcome among ibrutinib-treated patients with del13q, trisomy12, and negative FISH findings, we believe that routine monitoring of peripheral blood for emergence of resistant subclones is likely not necessary.

Management strategies in relapsed patients

If disease progression is suspected, this should be verified with further evaluation and testing. Progressive disease due to CLL relapse is very frequently secondary to acquired resistance to ibrutinib and as such testing for BTK and PLCG2 mutations would be in order, along with appropriate imaging studies. Richter’s transformation of CLL on the other hand tends to have a more aggressive and stormy clinical course and disease tends to be quite hypermetabolic on positron emission tomography (PET) imaging [43]. Tissue biopsy is essential to confirm Richter’s transformation of CLL diagnosis and distinguish it from progressive, relapsed CLL. Patients deemed to have relapsed CLL on ibrutinib are a particularly high-risk population and it is essential that ibrutinib not be discontinued until a subsequent therapy is planned [44].

Our first priority for relapsing patients is disease stabilization as indicated. While it may be tempting to stop ibrutinib in light of progression, this could lead to rapid disease growth and clinical deterioration. As such, it is paramount to recognize that ibrutinib should not be stopped immediately, and is best continued until the patient is ready to proceed with the next line of treatment. Whenever possible, we aim to enroll patients in clinical trials. For those requiring a washout period prior to enrollment, it is important to follow them closely due to the risk of rapid clinical decline. If permissible, a short course of high-dose steroids and an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody may be used.

Outside of a clinical trial, we consider venetoclax therapy – particularly if del17p13/TP53 mutation is present. Venetoclax targets BCL-2 and has demonstrated safety and efficacy in CLL [45,46], is effective in patients relapsing on ibrutinib [47], and is currently FDA and EMA-approved for relapsed CLL with del17p13. For patients without del17p13/TP53 mutation, we consider idelalisib (a PI3K-δ inhibitor that showed efficacy in relapsed CLL in combination with rituximab [48]). It is worth noting, however, that recent data have shown that therapy with idelalisib in this setting is not very effective [49]. Indeed, we try to use venetoclax in this situation even when del17p13/TP53 disruption is absent, which is currently an off-label approach. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines list venetoclax as a treatment option in the relapsed setting in patients with del17p13/TP53 mutation. It is also listed as an option in relapsed patients without del17p13/TP53 mutation, particularly if the patient is deemed unsuitable for ibrutinib or idelalisib [50]. The European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) guidelines recommend venetoclax in the relapsed setting in patients who failed BCR inhibition, are unsuitable for BCR inhibitor therapy, or harbor del17p13/TP53 mutation. These guidelines also recommend venetoclax in the frontline setting in patients with del17p13/TP53 mutation who are not suitable for BCR inhibitor therapy [51].

Patients who have not been exposed to chemoimmunotherapy prior to ibrutinib may potentially be evaluated for such treatment, particularly if no del17p13/TP53 mutation is present. Data for such an approach, however, is lacking as most patients relapsing on ibrutinib have already received some form of chemoimmunotherapy in the frontline setting.

Long-term disease control is unlikely to occur with the use of targeted therapies. The use of cellular therapies such as allogeneic stem cell transplant and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy may be considered in these patients. Reduced-intensity allogeneic stem cell transplantation can result in long-term disease control and its outcomes have improved in recent years [52]. Nevertheless, this approach is still associated with significant treatment-related morbidity and many patients with relapsed disease are ineligible for an allogeneic transplant by virtue of age, comorbidities, and performance status. Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy has garnered much attention recently in the arena of cellular therapy and has shown promise in ibrutinib-refractory CLL, with an ORR of 77% in ibrutinib-refractory or intolerant patients [53]. Although toxicity can be significant, responses tend to be durable.

Treatment of Richter’s transformation of CLL poses a significant challenge and patients tend to do poorly. Chemoimmunotherapy is generally ineffective in these patients. An exception perhaps may be those with clonally unrelated transformation in the absence of complex cytogenetics [44]. Immunotherapy with the checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab is currently under investigation and has shown promise in this population, with an ORR of 44% in a phase 2 study [54]. The combination of ibrutinib and nivolumab has also shown impressive response rates in patients with Richter’s transformation of CLL, with an ORR of 50% [55].

Future directions

Given the efficacy of therapies targeting the BCR pathway, it is no surprise that several investigational agents currently in the pipeline are aimed at sites downstream of BTK or alternative targets on BTK itself, in an effort to overcome acquired resistance to BTK inhibitors (Table 3). For instance, the reversible BTK inhibitor ARQ-531 binds to a site outside the C481 residue and has been shown to inhibit both wild-type and C481S mutated CLL in a murine model [56]. SNS-062 is another reversible BTK inhibitor that demonstrated preclinical efficacy in CLL cell lines [57] and is currently being evaluated in a phase 1b/2 clinical trial [NCT03037645]. Another target of interest is PKC-β, which is downstream of PLCG2. The PKC inhibitor sotastaurin (AEB071) demonstrated preclinical activity in CLL, both in vitro and in vivo [58]. Entospletinib (GS-9973) is a Syk inhibitor with potential activity in relapsed patients exposed to prior BTK or PI3K-δ inhibition based on results of a phase 2 trial [59]. Fifteen patients with prior BTK inhibition were evaluable for response and of these three developed a partial response and nine developed stable disease. One interesting approach to targeting the BCR pathway is suppression of BTK gene expression. The XPO1/CRM1 inhibitor selinexor (KPT-330) has been shown to achieve that and is active in preclinical models of CLL with ibrutinib resistance [60]. One of selinexor’s limitations however is significant systemic toxicity. As such, a newer XPO1 inhibitor (KPT-8602) with similar in vitro potency and improved in vivo tolerability has been developed [61]. Clinical data for many of the above agents remains to be seen.

Table 3.

New therapies in the pipeline for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

| Drug |

Mechanism of action |

Study phase |

Registration number |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pembrolizumab | Anti-PD1 monoclonal antibody | 2 | NCT02332980 | [54] |

| Nivolumab | Anti-PD1 monoclonal antibody | 2 | NCT02420912 | [55] |

| ARQ-531 | Reversible BTK inhibitor | Preclinical | N/A | [56] |

| SNS-062 | Reversible BTK inhibitor | 1b/2 | NCT03037645 | [57] |

| Sotastaurin (AEB071) | PKC inhibitor | Preclinical | N/A | [58] |

| Entospletinib (GS-9973) | Syk inhibitor | 2 | NCT01799889 | [59] |

| Selinexor (KPT-330) | XPO1/CRM1 inhibitor | Preclinical | N/A | [60] |

| KPT-8602 | XPO1 inhibitor | Preclinical | N/A | [61] |

Conclusions

Relapsed CLL on ibrutinib therapy is an increasingly recognized and growing problem that is primarily driven by the development of drug resistance secondary to acquired BTK and/or PLCG2 mutations. While these mutations can be detected many months prior to clinical progression, there is currently no standard approach to treatment modification and subsequent management planning. Furthermore, there is clearly a need for higher level evidence to inform decision making in relapsed patients.

Identifying high-risk patients earlier can help tailor follow-up and monitoring and potentially provide both patients and providers more time to plan ahead for the next steps in management. These are certainly exciting times in CLL treatment with regards to current and emerging therapies; it is no secret however that much work remains to be done and questions to be answered.

Acknowledgements

Sameer A. Parikh is a Scholar in the Mayo Clinic Paul Calabresi Program in Translational Research (K12 CA090628).

Funding

A.O. A.: None. S. A. P.: Research Support (no personal compensation): Pharmacyclics, Morphosys, Abbvie and Advisory Board (no personal compensation): Pharmacyclics, AstraZeneca, Abbvie.

Footnotes

Potential conflict of interest: Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article online at https://doi.org/10.1080/10428194.2017.1397665.

References

- [1].Hallek M, Fischer K, Fingerle-Rowson G, et al. Addition of rituximab to fludarabine and cyclophosphamide in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2010;376: 1164–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Tam CS, O’Brien S, Wierda W, et al. Long-term results of the fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab regimen as initial therapy of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2008;112:975–980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Eichhorst B, Fink AM, Bahlo J, et al. First-line chemoimmunotherapy with bendamustine and rituximab versus fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab in patients with advanced chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL10): an international, open-label, randomised, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:928–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Goede V, Fischer K, Busch R, et al. Obinutuzumab plus chlorambucil in patients with CLL and coexisting conditions. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1101–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Robak T, Dmoszynska A, Solal-Celigny P, et al. Rituximab plus fludarabine and cyclophosphamide prolongs progression-free survival compared with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide alone in previously treated chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1756–1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Fischer K, Bahlo J, Fink AM, et al. Long-term remissions after FCR chemoimmunotherapy in previously untreated patients with CLL: updated results of the CLL8 trial. Blood. 2016;127:208–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Thompson PA, Tam CS, O’Brien SM, et al. Fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab treatment achieves long-term disease-free survival in IGHV-mutated chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2016;127: 303–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Byrd JC, Furman RR, Coutre SE, et al. Three-year follow-up of treatment-naïve and previously treated patients with CLL and SLL receiving single-agent ibrutinib. Blood. 2015;125:2497–2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Jain P, Keating M, Wierda W, et al. Outcomes of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia after discontinuing ibrutinib. Blood. 2015;125:2062–2067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Maddocks KJ, Ruppert AS, Lozanski G, et al. Etiology of ibrutinib therapy discontinuation and outcomes in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:80–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Parikh SA, Chaffee KR, Call TG, et al. Ibrutinib therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL): an analysis of a large cohort of patients treated in routine clinical practice [abstract]. Blood. 2015;126:Abstract 2935. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Brown JR, Barrientos JC, Barr PM, et al. The Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor ibrutinib with chemoimmunotherapy in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2015;125:2915–2922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Piggin A, Bayly E, Tam CS. Novel agents versus chemotherapy as frontline treatment of CLL. Leuk Lymphoma. 2017;58:1320–1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Shustik C, Bence-Bruckler I, Delage R, et al. Advances in the treatment of relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Ann Hematol. 2017;96:1185–1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Byrd JC, Furman RR, Coutre SE, et al. Targeting BTK with ibrutinib in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:32–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Cheson BD, Byrd JC, Rai KR, et al. Novel targeted agents and the need to refine clinical end points in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30: 2820–2822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Byrd JC, Brown JR, O’Brien S, et al. Ibrutinib versus ofatumumab in previously treated chronic lymphoid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:213–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Brown JR, Hillmen P, O’Brien S, et al. Extended follow-up and impact of high-risk prognostic factors from the phase 3 RESONATETM study in patients with previously treated CLL/SLL. Leukemia. [cited 2017 Jun 8]. DOI: 10.1038/leu.2017.175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].O’Brien SM, Furman RR, Coutre SE, et al. Five-year experience with single-agent ibrutinib in patients with previously untreated and relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic leukemia [abstract]. Blood. 2016;128:Abstract 233. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Burger JA, Tedeschi A, Barr PM, et al. Ibrutinib as initial therapy for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2425–2437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].O’Brien S, Jones JA, Coutre SE, et al. Ibrutinib for patients with relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukaemia with 17p deletion (RESONATE-17): a phase 2, open-label, multicentre study. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:1409–1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Farooqui MZ, Valdez J, Martyr S, et al. Ibrutinib for previously untreated and relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukaemia with TP53 aberrations: a phase 2, single-arm trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:169–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Herman SEM, Niemann CU, Farooqui M, et al. Ibrutinib-induced lymphocytosis in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: correlative analyses from a phase II study. Leukemia. 2014;28:2188–2196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Woyach JA, Smucker K, Smith LL, et al. Prolonged lymphocytosis during ibrutinib therapy is associated with distinct molecular characteristics and does not indicate a suboptimal response to therapy. Blood. 2014;123:1810–1817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Mato AR, Nabhan C, Barr PM, et al. Outcomes of CLL patients treated with sequential kinase inhibitor therapy: a real world experience. Blood. 2016;128: 2199–2205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Woyach JA, Ruppert AS, Guinn D, et al. BTK(C481S)-mediated resistance to ibrutinib in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:1437–1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Ahn IE, Underbayev C, Albitar A, et al. Clonal evolution leading to ibrutinib resistance in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2017;129:1469–1479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Parikh SA, Rabe KG, Call TG, et al. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (Richter syndrome) in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL): a cohort study of newly diagnosed patients. Br J Haematol. 2013;162:774–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Herman SE, Gordon AL, Hertlein E, et al. Bruton tyrosine kinase represents a promising therapeutic target for treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia and is effectively targeted by PCI-32765. Blood. 2011;117: 6287–6296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Burger JA, Landau DA, Taylor-Weiner A, et al. Clonal evolution in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia developing resistance to BTK inhibition. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Woyach JA, Furman RR, Liu TM, et al. Resistance mechanisms for the Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor ibrutinib. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2286–2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Liu TM, Woyach JA, Zhong Y, et al. Hypermorphic mutation of phospholipase C, γ2 acquired in ibrutinib-resistant CLL confers BTK independency upon B-cell receptor activation. Blood. 2015;126:61–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Fama R, Bomben R, Rasi S, et al. Ibrutinib-naive chronic lymphocytic leukemia lacks Bruton tyrosine kinase mutations associated with treatment resistance. Blood. 2014;124:3831–3833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Kadri S, Lee J, Fitzpatrick C, et al. Clonal evolution underlying leukemia progression and Richter transformation in patients with ibrutinib-relapsed CLL. Blood Adv. 2017;1:715–727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Kay NE, O’Brien SM, Pettitt AR, et al. The role of prognostic factors in assessing ‘high-risk’ subgroups of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia.Leukemia. 2007;21:1885–1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Davids MS, Brown JR. Targeting the B cell receptor pathway in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2012;53:2362–2370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Haferlach C, Dicker F, Schnittger S, et al. Comprehensive genetic characterization of CLL: a study on 506 cases analysed with chromosome banding analysis, interphase FISH, IgV(H) status and immunophenotyping. Leukemia. 2007;21:2442–2451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Thompson PA, O’Brien SM, Wierda WG, et al. Complex karyotype is a stronger predictor than del(17p) for an inferior outcome in relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients treated with ibrutinib-based regimens. Cancer. 2015;121:3612–3621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Rossi D, Gerber B, Stussi G. Predictive and prognostic biomarkers in the era of new targeted therapies for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2017;58:1548–1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Heerema NA, Byrd JC, Cin PD, et al. Stimulation of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) cells with CpG oligodeoxynucleotide (ODN) gives consistent karyotypic results among laboratories: a CLL research consortium (CRC)h study. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2010;203: 134–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Muthusamy N, Breidenbach H, Andritsos L, et al. Enhanced detection of chromosomal abnormalities in chronic lymphocytic leukemia by conventional cytogenetics using CpG oligonucleotide in combination with pokeweed mitogen and phorbol myristate acetate. Cancer Genet. 2011;204:77–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Finnes HD, Chaffee KG, Call TG, et al. Pharmacovigilance during ibrutinib therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)/small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL) in routine clinical practice. Leuk Lymphoma. 2017;58:1376–1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Bruzzi JF, Macapinlac H, Tsimberidou AM, et al. Detection of Richter’s transformation of chronic lymphocytic leukemia by PET/CT. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:1267–1273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Woyach JA. How I manage ibrutinib-refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2017;129:1270–1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Roberts AW, Davids MS, Pagel JM, et al. Targeting BCL2 with venetoclax in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:311–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Stilgenbauer S, Eichhorst B, Schetelig J, et al. Venetoclax in relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukaemia with 17p deletion: a multicentre, open-label, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17: 768–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Jones J, Choi MY, Mato AR, et al. Venetoclax (VEN) monotherapy for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who relapsed after or were refractory to ibrutinib or idelalisib [abstract]. Blood. 2016;128: Abstract 637. [Google Scholar]

- [48].Furman RR, Sharman JP, Coutre SE, et al. Idelalisib and rituximab in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:997–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Mato AR, Hill BT, Lamanna N, et al. Optimal sequencing of ibrutinib, idelalisib, and venetoclax in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: results from a multicenter study of 683 patients. Ann Oncol 2017;28:1050–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia/Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma (Version 1.2018). [Internet]; [cited 2017 Oct 9] Available from: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/cll.pdf.

- [51].European Society for Medical Oncology. Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia Treatment Recommendations. [Internet]; [cited 2017 Oct 9] Available from: http://www.esmo.org/Guidelines/Haematological-Malignancies/Chronic-Lymphocytic-Leukaemia/eUpdate-TreatmentRecommendations.

- [52].Brown JR, Kim HT, Armand P, et al. Long-term follow-up of reduced-intensity allogeneic stem cell transplantation for chronic lymphocytic leukemia: prognostic model to predict outcome. Leukemia.2013;27:362–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Turtle CJ, Hanafi L-A, Li D, et al. CD19 CAR-T cells are highly effective in ibrutinib-refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia [abstract]. Blood. 2016;128:Abstract 56. [Google Scholar]

- [54].Ding W, LaPlant BR, Call TG, et al. Pembrolizumab in patients with CLL and Richter transformation or with relapsed CLL. Blood. 2017;129:3419–3427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Jain N, Basu S, Thompson PA, et al. Nivolumab combined with ibrutinib for CLL and Richter transformation: a phase II trial [abstract]. Blood. 2016;128: Abstract 59. [Google Scholar]

- [56].Reiff SD, Mantel R, Smith LL, et al. The Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor ARQ 531 effectively inhibits wild type and C481S mutant BTK and is superior to ibrutinib in a mouse model of chronic lymphocytic leukemia [abstract]. Blood. 2016;128:Abstract 3232. [Google Scholar]

- [57].Fabian CA, Reiff SD, Guinn D, et al. SNS-062 demonstrates efficacy in chronic lymphocytic leukemia in vitro and inhibits C481S mutated Bruton tyrosine kinase [abstract]. Cancer Res. 2017;77:Abstract 1207. [Google Scholar]

- [58].El-Gamal D, Williams K, LaFollette TD, et al. PKC-beta as a therapeutic target in CLL: PKC inhibitor AEB071 demonstrates preclinical activity in CLL. Blood. 2014;124:1481–1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Sharman JP, Shustov AR, Smith MR, et al. Updated results on the clinical activity of entospletinib (GS-9973), a selective Syk inhibitor, in patients with CLL previously treated with an inhibitor of the B-cell receptor signaling pathway [abstract]. Blood. 2016;128:Abstract 3225. [Google Scholar]

- [60].Hing ZA, Mantel R, Beckwith KA, et al. Selinexor is effective in acquired resistance to ibrutinib and synergizes with ibrutinib in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2015;125:3128–3132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Hing ZA, Fung HY, Ranganathan P, et al. Next-generation XPO1 inhibitor shows improved efficacy and in vivo tolerability in hematological malignancies. Leukemia. 2016;30:2364–2372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Fabbri G, Khiabanian H, Holmes AB, et al. Genetic lesions associated with chronic lymphocytic leukemia transformation to Richter syndrome. J Exp Med.2013;210:2273–2288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]