Abstract

This study examined racial and ethnic differences in professional service use by older African Americans, Black Caribbeans, and Non-Hispanic Whites in response to a serious personal problem. The analytic sample (N=862) was drawn from the National Survey of American Life. Findings indicated that African Americans and Black Caribbeans were less likely to use services than Whites. Type and race of providers seen varied by respondents’ race and ethnicity. Among respondents who did not seek professional help, reasons for not seeking help varied by ethnicity. Study findings are discussed in relation to practice implications.

Keywords: older adults, formal social support, professional help-seeking, Black Caribbeans

Older adults seek professional advice and support from physicians, social workers, and other service providers when confronted with a serious health or mental health problem. Research on professional service use among older adults focuses primarily on the domains of health and medical care (e.g., long-term care, assistance with ADLs and IDLs, chronic disease management and mental or cognitive disabilities). Studies of professional service use when experiencing personal difficulties (e.g., emotional difficulties, interpersonal problems, economic problems), is less common, but nonetheless important. For instance, the death of a loved one, marital problems, and having an adult child with mental health or substance abuse problems are not mental disorders, but are the types of issues for which older adults may seek counseling. This study examines the correlates of professional service use for personal problems and health issues within a sample of African American, Black Caribbean and non-Hispanic White adults aged 55 and older. In addition to potential race (Black/White) differences among older adults, we also examine ethnic differences (African American/Black Caribbean) in professional service use. The literature review provides: 1) an overview of race comparative research on professional service use within the general population and among older adults, 2) information on professional service use specifically among African Americans, and 3) a discussion of available research on professional service use patterns for Black Caribbean immigrants in the U.S.

Race Differences in Service Use

Race comparative research consistently demonstrates disparities in the use of professional services indicating that Blacks are less likely to seek professional help than Whites (Woodward, 2011). Woodward’s (2011) study found that 16% of African Americans, as compared to 10% of Whites, did not seek professional or informal help for a personal problem. Similarly, older African Americans were more likely than older Whites to indicate that they did not seek help in response to a serious personal problem (Woodward, Chatters, Taylor, Neighbors, & Jackson, 2010). Other research indicates that Blacks are less likely than White to use mental health services (Neighbors et al., 2007). For example, only 32% of Black Americans with a mental disorder used professional services (Neighbors et al., 2007); this compares with 41% who used services in a study of the overall population (Wang et al., 2005). Although Blacks are less likely than Whites to visit a counselor, therapist, or doctor for depression and less likely to receive any form of treatment for depression, they are more likely to visit the emergency room or be hospitalized for depression (Hankerson et al., 2011). Similarly, Hu et al.’s (1991) study on racial differences in mental health service use indicated that Black respondents were less likely than Whites to use case management and individual outpatient services, but were more likely to visit the emergency room.

Professional Service Use Among African Americans

A growing body of studies examines patterns and factors associated with professional service use among African Americans generally and among older adults. Overall, roughly half of older African Americans seek professional assistance for a stressful personal problem alone or in conjunction with informal support (Woodward et al., 2010). Problem type is associated with the likelihood of seeking help (Woodward et al., 2010), as well as where individuals go for help. For example, as compared to other problem types, physical health problems increase the likelihood of seeking assistance. Further, both physical health problems and death of a loved one are associated with seeking help from clergy (Taylor, Woodward, Chatters, Mattis, & Jackson, 2011). On the other hand, interpersonal and economic problems are the most common reasons for seeking assistance from social services (Neighbors & Taylor, 1985), while persons experiencing emotional problems are more likely to seek help from a psychologist or psychiatrist (Neighbors, 1985).

Similar to research findings for the general elderly population, African American older adults are less likely to use mental health services than their younger counterparts (Mackenzie, Pagura, & Sareen, 2010). This is evident even within older age groups, such that while 25% of persons 55 to 64 years seek help from mental health professionals, only 10% of 65 to 74 year olds and 9% of adults 75 and older do so (Mackenzie et al., 2010). Despite indicating a need for help with a mental disorder, virtually all persons 75 years and older did not seek assistance, as compared to 11% of adults 65 to 74 (Mackenzie et al., 2010).

Neighbors’s (1988) study of service use indicated that only 55% of African American adults who reported ‘feeling at the point of a nervous breakdown’ sought professional help. Further, only 7% of older African Americans used any kind of professional services for mental health problems (Neighbors et al., 2008). Roughly 20% sought help for a serious personal problem from the emergency room, physicians, or clergy, in contrast to 5% who sought help from a psychiatrist or psychologist, indicating a preference for traditional medical care services or religious leaders, as compared to specialty mental health services. Similar findings within the general population, indicate that the majority of individuals with a mental health disorder seek professional help from a general medicine provider (44%), followed by specialty mental health (38%) (Narrow, Regier, Rae, Manderscheid, & Locke, 1993).

While there are some comparability findings from the general population, several studies suggest that race and age may be important in shaping distinctive sources and patterns of professional service use for older African Americans. For example, 16% of older adults within the general population sought help from a mental health professional (Mackenzie et al., 2010). This is comparable to older African Americans, who are even less likely (7%) to report seeking professional help for mental health problems and who most often sought assistance from general medical providers (5%) (Neighbors et al., 2008). Over a third of older African Americans with a diagnosed mental disorder sought help from general medical providers, and 1 in 5 sought help from a specialty mental health provider (Neighbors et al., 2008). Service provider preference is also influenced by age indicating that persons 65 and older are less likely to use mental health and general medical services for mental health problems than persons aged 55 to 64 (Neighbors et al., 2008). Overall, older adults rarely rely on professional services alone (6.6%), with the majority (84%) combining professional services and informal support from family and friends (Woodward et al., 2010). Finally, due to the centrality of religious communities and leaders within the African American community (Taylor, Chatters, & Levin, 2004), clergy are often sought for assistance with a wide range of personal difficulties, including mental health issues. For example, in a study of African American adults (18 years and older), clergy was the most frequently cited (21%) source of professional support for individuals reporting a serious personal problem, followed by family doctors and psychiatrists. However, older adults were more likely to seek help from their ministers (Chatters et al., 2011).

Professional Service Use among Black Caribbeans in the U.S.

Ethnic diversity within the Black population is a rarely explored issue in research that contributes to an inadequate appreciation of within group variability in a range of social and health behaviors, including professional service use. Ethnic diversity within the American Black population has been steadily increasing, due in large part to the steady growth of the Black immigrant population. Among Black immigrants in the U.S., Black Caribbeans comprise 50% of this population (Anderson, 2015). Black Caribbeans are a substantial percentage of the overall U.S. Black population growth and comprise a significant portion of the Black population in urban centers (McKinnon, 2001). The majority of Black Caribbean immigrants reside either in the Northeast or South, with major concentrations in New York, Boston, Miami, and Fort Lauderdale (Anderson, 2015). Black Caribbeans make up over one quarter of the Black population in the New York and Boston metropolitan areas (Anderson, 2015).

Although Black Caribbeans and African Americans share a common racial heritage, Black Caribbeans are ethnically distinct from African Americans. In addition to cultural differences, Black Caribbeans differ from African Americans on a wide range of characteristics, including demographic characteristics, religion, language, national origin, and immigration history. Compared to African Americans, Black Caribbeans have higher income and educational attainment and while over half of African Americans identify as Baptist (Taylor et al., 2004), only 22% of Black Caribbeans identify as Baptist with 20% identifying as Catholic (compared to 6% of African Americans) (Nguyen, Taylor, & Chatters, 2016). The majority of Black Caribbeans are English speakers and are more likely to be English proficient than the overall immigrant population.

Immigration history and status are two prominent factors that distinguish Black Caribbeans from African Americans. Both factors play a significant role in shaping the social and health status of Black Caribbeans, as well as differences in outcomes as compared to Black ethnic groups in the U.S. Migration is recognized as a stressful and disruptive process that involves being uprooted from one’s home, community, family, and friends and relocated to a new and foreign setting with unfamiliar customs and traditions. Consequently, migration can be a disorienting event that is often accompanied by a sense of traumatic loss and unresolved grief. Available literature on service use, especially for mental health problems, among Black Caribbeans in the U.S. is very limited. The scarce evidence on service use among Black Caribbeans indicates that roughly (26%) of this population do not seek help for mental health problems (Woodward, 2011). For those who do seek help for mental health problems, the majority use both professional services and informal sources of assistance (47%) while comparatively few receive help from professional helpers only (12%) (Woodward, 2011). Using a national probability sample of Black Caribbeans in the U.S., Taylor et al. (2011) found that clergy (14%), mental health professionals (13%), and family doctors (13%) were the most common types of professionals that were used in response to a serious personal problem.

Research on ethnic comparisons in professional service use indicates that as compared to African Americans, Black Caribbeans are more likely to seek informal help only than to use both informal and professional help (Woodward et al., 2010). In a study of mental health service use, about a quarter of African American mothers with a mood disorder sought professional help, but less than one in five Black Caribbean mothers with a mood disorder sought professional help (Boyd, Joe, Michalopoulos, Davis, & Jackson, 2011). Woodward et al.’s (2011) research on Black men and service use for mental disorders found that relative to African American men, Black Caribbean men are more likely to seek both informal and professional help than informal help only.

Focus of the Present Study

The current study addresses the dearth of research on professional service use for personal problems among older adults, as well as explores racial and ethnic differences in older adult service use. This analysis examines racial and ethnic differences in the number and type of professional helpers sought by older African Americans, Black Caribbeans, and Non-Hispanic whites in response to a serious personal problem. This study also identified the race of professionals respondents visited, and, among respondents who did not seek professional help, the reasons for not seeking professional assistance.

Methods

Sample

This study uses data from the National Survey of American Life: Coping with Stress in the 21st Century (NSAL), a national multi-stage probability design survey (Jackson et al., 2004). The field work for the study was conducted from 2001 to 2003 by the Institute for Social Research Survey Research Center, University of Michigan in cooperation with the Program for Research on Black Americans. Most of the interviews were conducted face-to-face (86%) in respondents’ homes, while the remaining 14% were telephone interviews. The overall response rate was 72.3% with response rates of 70.7% for African Americans, 77.7% for Black Caribbeans, and 69.7% for Non-Hispanic Whites. A total of 6,082 interviews were conducted with persons aged 18 or older, including 3,570 African Americans, 891 Non-Hispanic Whites, and 1,621 Black Caribbeans. Roughly three-quarters (77.49%) of NSAL respondents indicated that they had experienced a serious personal problem. The analytic sample for this study is comprised of the 862 of these respondents who are aged 55 and older.

Both the African American and Black Caribbean samples required that respondents self-identify their race as Black. Those self-identifying as Black were included in the Black Caribbean sample if they indicated they were of West Indian or Caribbean descent, said they were from a country included on a list of Caribbean area countries presented by the interviewers, or indicated that their parents or grandparents were born in a Caribbean area country and who are English-speaking (but may also speak another language). Particularly important for this study, the NSAL includes the first major probability sample of Black Caribbeans ever conducted. The Black Caribbean sample was selected from two area probability sample frames: the core NSAL sample and housing units from geographic areas with a relatively high density of persons of Caribbean descent. For a more detailed discussion of the NSAL sample and instrumentation see (Jackson et al., 2004).

Measures

Respondents were first asked to report a personal problem they had experienced in their lives that had caused them a significant amount of distress. They were next asked to describe the nature of the problem. Respondents’ open-ended responses to this question were then recoded into a five-category variable indicating the type of problem reported: physical (e.g., poor health, accident), interpersonal (e.g., difficulties with close family and friends, divorce), emotional (e.g., depression, unhappiness, self-doubt), bereavement (death of a loved one), and economic (e.g., poor or declining financial status, loss of assets). Next, respondents were asked how they adapted to the stressful episode that they previously described. They were presented a list of professional service providers (psychiatrist, other mental health professionals, family doctor, other doctor, other health professionals, religious/spiritual advisor, other healer, self-help group, other professional) and asked if they had talked to any of them about their problem. Dichotomous indicators were created for the use of four professionals: psychiatrist; other mental health professional (e.g., psychologist, psychotherapist, social worker, mental health nurse or counselor); family doctor; and clergy (religious or spiritual advisor) such as a minister, priest, rabbi, or pastor.

Two dependent variables assess whether: a) the respondent sought help from a professional helper (yes/no) and b) the number of professional helpers. Other dependent variables investigate whether or not the respondent sought help (yes/no) from each of four specific types of professional helper: psychiatrist, other mental health professional, family doctor, and clergy. Respondents were also asked the race/ethnicity of their professional helper. Lastly, those respondents who did not seek any professional help were asked the open-ended question “Why didn’t you ever go for professional help for that problem?”

Independent variables include type of problem reported, age, gender, marital status, years of education, household income, insurance coverage, and frequency of attending religious services. Age, years of education, and household income were assessed continuously. Gender was coded male=1 and female=2. Marital status was assessed categorically and differentiated between married and unmarried respondents. Insurance coverage was also assessed categorically and differentiated between public insurance, private insurance, and no insurance. Frequency of attending religious services was measured by the question, “How often do you usually attend religious services? Would you say nearly everyday, at least once a week, a few times a month, a few times a year, or less than once a year?”

Analysis Strategy

Percentages and means are weighted based on the sample’s race-adjusted weight measure. Bivariate analyses are tested using the Rao-Scott χ2,which is a complex design-adjusted version of the Pearson Chi-square test, and a complex design-adjusted F tests. Linear regression was used to analyze predictors of number of professional helpers utilized, and logistic regression was used to analyze predictors of all dichotomous dependent variables. Logistic regression is a type of predictive analysis that uses a logistic function to model dichotomous outcomes. Odds ratio, which measures the association between a predictor and the dichotomous outcome, is calculated in this type of regression. Odd ratio represents the likelihood that an event will occur expressed as a proportion of the likelihood that the event will not occur. The NSAL uses a multi-stage sample design, involving both clustering and stratification. Because most statistical techniques are based on the assumption that the study is based on a simple random sample, the analysis procedures used in this paper adjusted for the multi-stage complex design of the NSAL. Statistical weighting was also utilized to adjust for unequal probabilities of selection and nonresponse so that the analysis can be generalized to the entire population.

Results

The distribution of all study variables and their association with race/ethnicity are presented in Tables 1 and 2. Looking first at African Americans, a smaller proportion are married and a higher proportion have public health insurance as compared to Black Caribbeans and Non-Hispanic Whites. A higher proportion of Non-Hispanic Whites had private insurance coverage than African Americans and Black Caribbeans. With regard to the type of problem reported, a higher proportion of older Black Caribbeans reported a physical health or an emotional problem; more non-Hispanic Whites reported an interpersonal problem, and a higher proportion of older African Americans reported a bereavement issue.

Table 1.

Distribution of study variables.

| % (M) | N (S.D.) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 44.5 | 322 |

| Female | 55.5 | 540 |

| Age | 66.38 | 8.39 |

| Income | 39686 | 42142 |

| Education | 12.44 | 3.3 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Unmarried | 53.6 | 570 |

| Married | 46.4 | 292 |

| Insurance Status | ||

| No Insurance | 5 | 64 |

| Public coverage | 21.5 | 251 |

| Private coverage | 73.6 | 547 |

| Religious Service Attendance | 4.09 | 1.29 |

| Type of Problem | ||

| Physical | 20.4 | 174 |

| Interpersonal | 25.2 | 180 |

| Emotional | 14.9 | 96 |

| Bereavement | 27.3 | 255 |

| Economic | 12.3 | 123 |

| Professional Service Use | ||

| Any Professional | 62.1 | 462 |

| # of Professionals | 1.18 | 1.13 |

| Type of professional | ||

| Psychiatrist | 13.1 | 76 |

| Other mental health | 16.9 | 85 |

| Family Doctor | 34.9 | 264 |

| Clergy | 31.5 | 254 |

Percents are weighted; frequencies are unweighted. M= Mean, S.D. = Standard Deviation

Percents and N’s are presented for categorical variables.

Means and Standard Deviations are presented for continuous variables.

Table 2.

Bivariate relationships between study variables and race/ethnicity.

| African Americans |

Black Caribbeans |

Non-Hispanic Whites |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (M) | N (S.D.) | % (M) | N (S.D.) | % (M) | N (S.D.) | X2/F | |

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 42.4 | 170 | 49.4 | 68 | 45.4 | 84 | 0.4 |

| Female | 57.6 | 286 | 50.6 | 99 | 54.6 | 155 | |

| Age | 66.22 | 8.38 | 64.51 | 8.06 | 66.52 | 8.6 | 1.31 |

| Income | 35498 | 40646 | 44520 | 33092 | 41539 | 49425 | 0.95 |

| Education | 11.83 | 3.51 | 11.91 | 3.33 | 12.75 | 2.7 | 2.52 |

| Marital Status | |||||||

| Unmarried | 62.6 | 324 | 46.1 | 96 | 49.6 | 150 | 5.18** |

| Married | 37.4 | 132 | 53.9 | 71 | 50.4 | 89 | |

| Insurance Status | |||||||

| No Insurance | 7.5 | 38 | 7.2 | 14 | 3.7 | 12 | 7.91*** |

| Public coverage | 33.7 | 174 | 26.2 | 38 | 15.4 | 39 | |

| Private coverage | 58.8 | 244 | 66.6 | 115 | 80.9 | 188 | |

| Religious Service Attendance | 4.17 | 1.22 | 4.14 | 1.34 | 3.83 | 1.41 | 7.99*** |

| Type of Problem | |||||||

| Physical | 22.9 | 94 | 24.1 | 36 | 19 | 44 | 21.94* |

| Interpersonal | 17.6 | 86 | 15.3 | 36 | 29.2 | 58 | |

| Emotional | 11.2 | 43 | 28.4 | 16 | 16.3 | 37 | |

| Bereavement | 34.4 | 157 | 19.9 | 34 | 24.1 | 64 | |

| Economic | 14 | 59 | 12.4 | 36 | 11.5 | 28 | |

| Professional Service Use | |||||||

| Any Professional | 52.4 | 240 | 42.2 | 70 | 67.5 | 152 | 10.85*** |

| # of Professionals | 0.89 | 1.08 | 0.81 | 1.03 | 1.34 | 1.24 | 6.82** |

| Type of professional | |||||||

| Psychiatrist | 8.6 | 36 | 13.8 | 10 | 15.2 | 30 | 3.09* |

| Other mental health | 8.4 | 37 | 13.8 | 10 | 21.2 | 38 | 6.52** |

| Family Doctor | 31.8 | 146 | 18.2 | 40 | 37.1 | 78 | 2.06 |

| Clergy | 26.8 | 130 | 20.9 | 36 | 34.2 | 88 | 2.74 |

Percents are weighted; frequencies are unweighted. M= Mean, S.D. = Standard Deviation

Percents and N’s are presented for categorical variables.

Means and Standard Deviations are presented for continuous variables.

Rao-Scott X2 is used with categorical Variables and F test is used with continuous variables.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Roughly two out of three (62.1%) respondents sought assistance from at least one professional helper; the average number of professionals contacted was 1.18. A significantly higher proportion of non-Hispanic Whites contacted a professional helper and used more helpers on average. Overall, the highest proportion of respondents sought assistance from family doctors (34.9%) followed by clergy (31.5%), other mental health professionals (16.9%), and psychiatrists (13.1%). Significant bivariate race/ethnicity findings for professional service use indicated that older Non-Hispanic Whites were more likely than African American and Black Caribbean elderly to contact psychiatrists and other mental health professionals.

Table 3 presents linear and logistic regression analyses for race and ethnic differences in the use of professional services. The first set of analyses used African Americans as the excluded or comparison category whereas the second set uses Black Caribbeans as the excluded category. In comparison to African Americans, whites were more likely to use any professional and a greater number of professionals. Whites were also more likely than African Americans to use other mental health professionals and clergy. Compared to African Americans, Black Caribbeans were less likely to use a family doctor. Relative to Black Caribbeans, white respondents were more likely to use any professional and a greater number of professionals. Whites were also more likely to use other mental health professionals and clergy than Black Caribbeans. No significant race/ethnic differences in use of psychiatrists were found.

Table 3.

Linear and Logistic Regression Analysis of Race and Ethnic Differences in the Use of Professional Service Providers

| # of Professionalsa | Any Professionalb | Psychiatristb | Other Mental Health Professionalb | Family Doctorb | Clergyb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (SE) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| African American | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Black Caribbean | −0.13 (0.26) | 0.60 (0.29–1.23) | 1.39 (0.35–5.70) | 1.38 (0.37–5.22) | 0.42 (0.19–0.95)* | 0.80 (0.45–1.45) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 0.41 (0.09)* | 2.16 (1.45–3.20)* | 1.24 (0.64–2.41) | 2.44 (1.23–4.85)* | 1.37 (0.80–2.35) | 1.93 (1.30–2.87)* |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| Black Caribbean | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| African American | 0.13 (0.26) | 1.67 (0.81–3.43) | 0.72 (0.18–2.86) | 0.72 (0.19–2.72) | 2.39 (1.06–5.40)* | 1.24 (0.69–2.24) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 0.54 (0.26)* | 3.60 (1.68–7.71)* | 0.89 (0.23–3.44) | 1.77 (0.43–7.29) | 3.28 (1.29–8.36)* | 2.40 (1.25–4.61)* |

B=Regression coefficient, SE=Standard Error

linear regression

OR=Odds Ratio, CI=Confidence Interval

logistic regression

p<.05

All analyses controlled for gender, age, income, education, marital status, insurance, religious service attendance and type of problem.

Results of the regression models for demographic, health insurance, service attendance and type of problem variables on use of professional helpers for the entire sample are presented in Table 4. (All analyses in Table 4 controlled for race/ethnicity.) Older adults with a physical or emotional problem were more likely to see a professional helper and saw more professional helpers, while those experiencing an economic problem reported fewer helpers compared to those coping with bereavement. Older persons who attended religious services more frequently were more likely to have used a professional helper.

Table 4.

Linear and Logistic Regression Analysis of Use of Professional Service Providers

| # of Professionalsa | Any Professionalb | Psychiatristb | Other Mental Health Professionalb | Family Doctorb | Clergyb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (SE) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | −0.06 (0.10) | 0.95 (0.50–1.83) | 0.49 (0.22–1.12) | 0.63 (0.30–1.31) | 0.68 (0.43–1.07) | 1.03 (0.66–1.60) |

| Female | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Age | 0.01 (0.01) | 1.03 (1.00–1.05) | 1.01 (0.96–1.06) | 1.00 (0.94–1.07) | 1.03 (1.01–1.06)* | 0.99 (0.96–1.02) |

| Income | 0.01 (0.01) | 1.01 (0.99–1.15) | 0.95 (0.88–1.02) | 1.02 (0.99–1.04) | 0.98 (0.91–1.04) | 1.01 (0.96–1.06) |

| Education | 0.04 (0.02) | 1.06 (0.99–1.15) | 1.12 (0.95–1.32) | 1.23 (1.11–1.37)* | 1.04 (0.94–1.15) | 1.04 (0.95–1.14) |

| Marital Status | ||||||

| Unmarried | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Married | 0.17 (0.15) | 1.12 (0.50–2.51) | 3.15 (0.93–10.73) | 1.12 (0.51–2.44) | 2.01 (0.93–4.32) | 0.80 (0.41–1.53) |

| Insurance Status | ||||||

| Private coverage | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Public coverage | −0.30 (0.23) | 0.48 (0.16–1.41) | 1.45 (0.29–7.23) | 0.73 (0.08–6.92) | 0.62 (0.22–1.69) | 0.64 (0.23–1.74) |

| No coverage | −0.47 (0.30) | 0.63 (0.20–1.96) | 1.59 (0.29–8.60) | 0.42 (0.05–3.86) | 0.50 (0.18–1.39) | 0.59 (0.18–1.93) |

| Religious Service Attendance | 0.07 (0.04) | 1.29 (1.11–1.49)* | 0.78 (0.65–0.94)* | 0.9 (0.73–1.11) | 1.06 (0.86–1.30) | 1.69 (1.38–2.07)* |

| Type of Problem | ||||||

| Bereavement | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Physical | 0.64 (0.11)* | 4.66 (2.76 – 7.85)* | 2.42 (1.16–5.03)* | 1.61 (0.47–5.48) | 6.2 (3.68–10.46)* | 0.97 (0.56–1.68) |

| Interpersonal | 0.01 (0.18) | 1.21 (0.72–2.03) | 2.37 (0.99–5.70) | 2.02 (0.47–8.67) | 0.84 (0.35–1.99) | 0.85 (0.56–1.39) |

| Emotional | 0.47 (0.18)* | 2.24 (1.11–4.52)* | 8.17 (2.70–24.77)* | 5.31 (1.84–15.35)* | 1.95 (0.77–4.99) | 0.53 (0.27–1.06) |

| Economic | −0.61 (0.70)* | 0.69 (0.38–1.27) | 0.25 (0.03–2.29) | 0.33 (0.06–1.73) | 1.17 (0.67–2.03) | 0.24 (0.10–0.55)* |

p<.05

B=Regression coefficient, SE=Standard Error

linear regression

OR=Odds Ratio, CI=Confidence Interval

logistic regression

All analyses controlled for race/ethnicity.

Several demographic and problem type characteristics were associated with use of specific professional helpers. Religious service attendance was inversely related to using a psychiatrist while those with physical health problems or emotional problems were more likely to utilize a psychiatrist in comparison to those with bereavement problems. Turning to other mental health professionals, education and type of problem were significantly associated. Older adults with more years of education and those with emotional problems had a higher likelihood of utilizing “other mental health professional.” With regard to use of a family doctor, older age increased use of a family doctor as did reporting a physical health problem. Lastly, religious service attendance was positively associated with use of clergy, and respondents experiencing bereavement were more likely to utilize clergy than those with economic problems (Table 4).

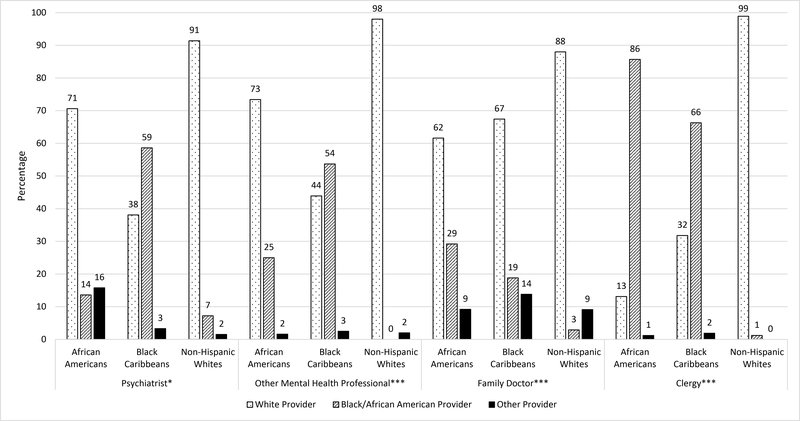

Figure 1 presents the bivariate analyses of race/ethnicity of service provider by race/ethnicity of respondent. Overall, respondents indicated that the professional helpers they utilized were more likely to be White. Among older non-Hispanic Whites, roughly 9 out of 10 of all professional helpers seen were White. A majority of older African Americans contacted psychiatrists (70%), other mental health professionals (73%) and family doctors (62%) who were White. With the exception of family doctors, a slim majority of older Black Caribbeans indicated that they saw psychiatrists and other mental health professionals who were Black/African American. With regard to race of clergy, the majority of African Americans (86%) and Black Caribbeans (66%) reported seeking help from clergy who were Black/African American, while the majority of non-Hispanic Whites reported seeking help from clergy who were White (99%).

Figure 1.

Bivariate Analysis of Race/Ethnicity of Professional Service Provider and Race/Ethnicity of Respondent

Note: Rao-Scott X2 was used to test for differences; *p<.05, ***p<.001

Finally, roughly a third of older persons indicated that they did not seek services for their serious personal problem. Table 5 presents the frequency distribution of reported reasons for not seeking professional help. For the sample overall, the top three reasons for not seeking professional services (in order of importance) were: “thought problem would get better by itself’ (without professional assistance),” “wanted to solve problem alone,” and “did not think that professionals would help.” A significantly higher proportion of older African Americans indicated that they ‘thought that the problem would get better by itself’ (33.9%) compared to non-Hispanic Whites (20.5%) and Black Caribbeans (16.9%). More Black Caribbeans (35.2%) and non-Hispanic Whites (29.8%) reported wanting to solve the problem alone compared to African Americans (16.2%). A higher proportion of African Americans (4.9%) and Black Caribbeans (4.3%) reported turning to God for help compared to Whites (.6%).

Table 5.

Reasons Why Respondents Did Not Seek Professional Assistance

| Total |

African Americans |

Black Caribbeans |

Non-Hispanic Whites |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | χ2 | |

| Thought problem would get better by itself | 25.7 | 109 | 33.9 | 77 | 16.9 | 15 | 20.5 | 17 | 5.39** |

| Felt better | 7.4 | 29 | 5.9 | 15 | 7.3 | 8 | 8.5 | 6 | 0.46 |

| Problem did not really bother respondent much | 5.7 | 34 | 7.5 | 16 | 14.9 | 12 | 3.8 | 6 | 2.23 |

| Wanted to solve problem alone | 24.5 | 86 | 16.2 | 35 | 35.2 | 28 | 29.8 | 23 | 4.08* |

| Did not think that professionals would help | 12.0 | 46 | 11.7 | 26 | 10.3 | 11 | 12.3 | 9 | 0.02 |

| Could not afford it; too expensive | 1.0 | 6 | 1.5 | 3 | 0.4 | 2 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.63 |

| Talked to friend, relative | 5.4 | 24 | 4.1 | 11 | 5.7 | 6 | 6.3 | 7 | 0.49 |

| Did not need help | 5.9 | 24 | 9.2 | 16 | 3.5 | 5 | 3.7 | 3 | 1.57 |

| Turned to God for help | 2.4 | 11 | 4.9 | 9 | 4.3 | 1 | 0.6 | 1 | 3.83* |

| Worried about what others would think | 1.0 | 4 | 1.4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0.9 | 1 | -- |

| Did not know where to go for help | 0.4 | 4 | 1.0 | 3 | 0.26 | 1 | 0 | 0 | -- |

| Embarrassed to talk about problem | 1.6 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 1 | 2.8 | 3 | -- |

| Did not want help | 0.1 | 1 | 0.4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -- |

| Too young, problem occurred when child | 2.5 | 3 | 0.6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2 | -- |

| Dislike doctors, afraid | 0.6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | -- |

| Financial | 0.0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.8 | 1 | 0 | 0 | -- |

Percentages are weighted; frequencies are unweighted.

p<.05

p<.01

Discussion

Perhaps the most striking finding from this study is that a third of older adults did not seek any professional services for their serious health and emotional problems, despite the fact that these were some of the most significant and distressing problems they had encountered. This is consistent with previous work documenting older adults’ lower service utilization (Mackenzie et al., 2010). Both African Americans and Black Caribbeans were less likely than non-Hispanic Whites to utilize professional services and contacted fewer professional helpers. These findings corroborate Black-White differences in professional service underutilization (Hankerson et al., 2011) and confirm this pattern for both older African Americans and Black Caribbeans (no ethnicity differences). Information on why respondents did not seek professional assistance indicated that older adults thought that the problem would get better without professional help. Respondents did not mention whether additional issues that have been identified for older adults (Wuthrich & Frei, 2015) such as financial problems or transportation difficulties played a role in their decision to try to solve a serious health or emotional problem alone. However, it is important to note that other work indicates that older adults who do not seek professional assistance receive some help from family and friends (Woodward et al., 2010).

The most utilized professional service providers were family doctor (34%) and clergy (31%), who were contacted twice as often as psychiatrist (13%) and other mental health professionals (17%). Consistent with findings from the National Comorbidity Study (Wang, Berglund, & Kessler, 2003) our findings confirm that clergy are sought for a range of personal difficulties, including mental health problems. Findings for specific professional helpers are noteworthy in several respects. First, use of psychiatrists was fairly low, and there were no significant race or ethnic differences. However, both older African Americans and Non-Hispanic Whites were more likely to utilize family doctors than Black Caribbeans, suggesting that Black Caribbeans may be less likely to have a usual source of care. Second, non-Hispanic Whites utilized clergy more than African Americans. This is inconsistent with research indicating that that older African Americans have more interactions with clergy (Krause, 2008). Further, there has been a general belief that clergy play a particularly important role in the delivery of mental health services to African Americans (Chatters et al., 2011). A recent analysis helps explain the inconsistencies in this body of research (Chatters et al., 2017). This work found that when seeking assistance for a serious problem, African Americans were more likely to see clergy in a church setting whereas non-Hispanic Whites were more likely to see clergy in other settings such as hospitals. African Americans’ contact with clergy within the context of church may be reflective of a long-standing relationship with a pastor or minister. For non-Hispanic Whites, in addition to contacts with their church pastor, their use of clergy may also reflect discrete events and circumstances (counseling from a hospital chaplain when hospitalized), increasing reports of clergy use. Thus, white respondents, especially those who reported physical or health related problems and issues with bereavement, may be seeking help from clergy in contexts outside of the church, such as the hospital or hospice facility. On the other hand, African American respondents’ use of clergy may be only within congregational contexts. This more restricted use of clergy is a possible explanation for why African American respondents had lower likelihood of seeking help from clergy relative to white respondents.

One of the unique aspects about the current analysis is that it includes the race of the professional service provider. Overall, except for clergy, older adults were overwhelmingly seen by White professionals. Roughly nine out of 10 older Whites indicate that they received assistance from White professionals. While the race of the professional helper was more diverse for African American and Black Caribbean older adults, the majority of both groups were seen by white psychiatrists, other mental health professionals, and family doctors. Ethnic comparisons show that older African Americans were more likely to receive assistance from white psychiatrists and other mental health professionals and Black/African American clergy, while older Black Caribbeans were more likely to contact a Black family doctor.

Several noteworthy relationships between problem type and use of professional services demonstrate how specific issues shape patterns and levels of service use. Older adults with physical and emotional problems were more likely (than those with bereavement) to seek out assistance and to engage multiple professionals. Respondents with emotional problems sought assistance from psychiatrists and other mental health professionals and were also more likely to seek assistance from multiple professional providers. The pattern of seeking mental health care from multiple providers may be an indicator of dissatisfaction with the treatment progress or reflect referrals to specialty care (Scott, Matsuyama, & Mezuk, 2011). These patterns confirm that the type of professional seen is substantially related to the diagnostic attribution (i.e., as a purely psychological state or a consequence of a physical health problem) of the problem (Neighbors, Musick, & Williams, 1998; Scott et al., 2011). However, physical health problems were associated with assistance from family doctors and psychiatrists--indicating the co-occurrence of physical health problems and mood disorders such as depression (Kang et al., 2015).

This study has a number of limitations that should be noted. Information about the timing and sequencing of help-seeking actions was not assessed. Given this, we have no information about the overall process of help-seeking, such as when and how older adults engaged professionals, involvement and sequencing of different professionals, types of help received in relation to specific issues, and perceived provider effectiveness. Information of this sort and prospective data would provide confidence about the causal ordering of help-seeking. Older adults who are homeless or institutionalized were not represented in the sample, so study findings are not generalizable to these groups.

Practice Implications

Despite these limitations, the current findings have several implications for practice. The overwhelming use of White professionals among all respondents calls into question the character of these relationships. Research has identified implicit bias in race discordant provider-client (White provider-Black client) interactions as a barrier to effective communication and affects client reactions to and trust in provider recommendations (Dovidio et al., 2008). Although our study is unable to address this issue, prior work suggests that aspects of race-discordant client-provider interpersonal exchanges may be a barrier to engaging professional services among older African Americans and Black Caribbeans. Perhaps this may partially explain the racial disparity in service use found in this study. Further, the results indicated that older African Americans and Black Caribbeans had lower rates of professional service use than older Whites. This highlights a need for a better understanding of barriers to service use that may be unique to Black Americans, such as discrimination. For example, Woodward et al. (2011) found that Black-White disparities in service use was non-existent when they accounted for discrimination, indicating that discrimination contributes to lower service use rates among Blacks. This suggests that efforts to address implicit racial bias (and recognition of historical explicit racial bias demonstrated helping professions) are critical to eliminating racial disparities in service use.

In sum, this investigation among African American, Black Caribbean and Non-Hispanic White older adults identified several problem type, sociodemographic, and religious correlates of professional service use for personal problems, as well as patterns and number of providers used. Use of clergy was prominent in seeking professional help for a variety of problems and professional use for physical problems included the use of psychiatrists as well as physicians. Race differences in professional service use confirmed prior findings of higher utilization by Non-Hispanic Whites (both any contact and number of professionals), while findings of greater use of clergy by non-Hispanic Whites was unexpected, but partially explained by the location of the therapeutic encounter. Also unanticipated was the absence of any effects of insurance status on professional services use. Novel contributions of this study include race of provider information that indicated that race discordance in provider-client interactions is prominent among African American and Black Caribbean older adults. Further, reasons for not seeking assistance indicated that African Americans were more likely than others to feel that the problem would resolve itself and Black Caribbeans were more likely to say that they wanted to solve the problem themselves. Finally, the inclusion of Black Caribbeans allowed the investigation of the role of ethnicity in relation to professional service use among Black older adults. These findings indicated that although ethnicity mattered in a few instances, overall race differences were more consistent.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: The preparation of this manuscript was supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging to RJT (P30AG1528) and HOT (R36AG054647) The data collection on which this study is based was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; U01-MH57716) with supplemental support from the Office of Behavioral and Social Science Research at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the University of Michigan.

Contributor Information

Ann W. Nguyen, Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel School of Applied Social Sciences, Case Western Reserve University

Robert Joseph Taylor, School of Social Work, University of Michigan

Linda M. Chatters, School of Public Health, School of Social Work, University of Michigan

Harry Owen Taylor, Brown School of Social Work, Washington University in St. Louis

Amanda Toler Woodward, School of Social Work, Michigan State University

References

- Anderson M (2015). A rising share of the U.S. Black population is foreign born: 9 percent are immigrants and while most are from the Caribbean, Africans drive recent growth. Retrieved from Washington, D.C.: [Google Scholar]

- Boyd RC, Joe S, Michalopoulos L, Davis E, & Jackson JS (2011). Prevalence of mood disorders and service use among US mothers by race and ethnicity: Results from the National Survey of American Life. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 72(11), 1538–1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatters LM, Mattis JS, Woodward AT, Taylor RJ, Neighbors HW, & Grayman NA (2011). Use of ministers for a serious personal problem among African Americans: Findings from the National Survey of American Life. Am J Orthopsychiatry, 81(1), 118–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01079.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatters LM, Taylor RJ, Woodward AT, Bohnert ASB, Peterson TL, & Perron BE (2017). Differences between African Americans and non-Hispanic Whites utilization of clergy for counseling with serious personal problems. Race and Social Problems, 9(2), 139–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dovidio JF, Penner LA, Albrecht TL, Norton WE, Gaertner SL, & Shelton JN (2008). Disparities and distrust: The implications of psychological processes for understanding racial disparities in health and health care. Soc Sci Med, 67(3), 478–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankerson SH, Fenton MC, Geier TJ, Keyes KM, Weissman MM, & Hasin DS (2011). Racial differences in symptoms, comorbidity, and treatment for major depressive disorder among black and white adults. Journal of the National Medical Association, 103(7), 576–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu T-W, Snowden LR, Jerrell JM, & Nguyen TD (1991). Ethnic populations in public mental health: services choice and level of use. American Journal of Public Health, 81(11), 1429–1434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JS, Torres M, Caldwell CH, Neighbors HW, Nesse RM, Taylor RJ,… Williams DR (2004). The National Survey of American Life: A study of racial, ethnic and cultural influences on mental disorders and mental health. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 13(4), 196–207. doi: 10.1002/mpr.177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang H-J, Kim S-Y, Bae K-Y, Kim S-W, Shin I-S, Yoon J-S, & Kim J-M (2015). Comorbidity of depression with physical disorders: research and clinical implications. Chonnam Medical Journal, 51(1), 8–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N (2008). Aging in the church: How social relationships affect health. West Conshohocken, PA: Templeton Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie CS, Pagura J, & Sareen J (2010). Correlates of Perceived Need for and Use of Mental Health Services by Older Adults in the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 18(12), 1103–1115. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181dd1c06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinnon J (2001). The black population: 2000. Retrieved from

- Narrow WE, Regier DA, Rae DS, Manderscheid RW, & Locke BZ (1993). Use of services by persons with mental and addictive disorders: Findings from the National Institute of Mental Health Epidemiologic Catchment Area Program. Archives of General Psychiatry, 50(2), 95–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors HW (1985). Seeking professional help for personal problems: Black American’s use of health and mental health services. Community Mental Health Journal, 21(3), 156–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors HW (1988). The help-seeking behavior of black Americans. A summary of findings from the National Survey of Black Americans. Journal of the National Medical Association, 80(9), 1009–1012. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors HW, Caldwell C, Williams DR, Nesse R, Taylor RJ, Bullard KM,… Jackson JS (2007). Race, ethnicity, and the use of services for mental disorders: Results from the National Survey of American Life. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64(4), 485–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors HW, Musick MA, & Williams DR (1998). The African American minister as a source of help for serious personal crises: Bridge or barrier to mental health care? Health Education & Behavior, 25(6), 759–777. doi: 10.1177/109019819802500606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors HW, & Taylor RJ (1985). The use of social service agencies by black Americans. Social Service Review, 59(2), 258–268. [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors HW, Woodward AT, Bullard KM, Ford BC, Taylor RJ, & Jackson JS (2008). Mental health service use among older African Americans: The National Survey of American Life. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 16(12), 948–956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen AW, Taylor RJ, & Chatters LM (2016). Church-based social support among Caribbean Blacks in the United States. Review of Religious Research, 58, 385–406. doi: 10.1007/s13644-016-0253-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott T, Matsuyama R, & Mezuk B (2011). The relationship between treatment settings and diagnostic attributions of depression among African Americans. Gen Hosp Psychiatry, 33(1), 66–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, & Levin J (2004). Religion in the lives of African Americans: Social, psychological, and health perspectives. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Woodward AT, Chatters LM, Mattis JS, & Jackson JS (2011). Seeking help from clergy among black Caribbeans in the United States. Race and Social Problems, 3(4), 241–251. doi: 10.1007/s12552-011-9056-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PS, Berglund PA, & Kessler RC (2003). Patterns and correlates of contacting clergy for mental disorders in the United States. Health Services Research, 38(2), 647–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, & Kessler RC (2005). Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), 629–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward AT (2011). Discrimination and help-seeking: Use of professional services and informal support among African Americans, Black Caribbeans, and Non-Hispanic Whites with a mental disorder. Race and Social Problems, 3(3), 146–159. doi: 10.1007/s12552-011-9049-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward AT, Chatters LM, Taylor RJ, Neighbors HW, & Jackson JS (2010). Differences in professional and informal help seeking among older African Americans, Black Caribbeans and non-Hispanic Whites. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 1(3), 124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward AT, Taylor RJ, & Chatters LM (2011). Use of professional and informal support by Black men with mental disorders. Research on Social Work Practice, 21(3), 328–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuthrich VM, & Frei J (2015). Barriers to treatment for older adults seeking psychological therapy. International Psychogeriatrics, 27(7), 1227–1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]