Abstract

The present study examined the impact of parental knowledge and attitudes about attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and parental perceptions of treatment response on the utilization of behavioral and pharmacological ADHD treatments, using data from a longitudinal treatment study designed to assess physical growth in children with ADHD. It also explored if these relations were moderated by race/ethnicity. Participants include 230 (74% Hispanic) families of treatment naïve children with ADHD (M age = 7.56, SD = 1.94; 73% male). Families were randomly assigned to receive behavior therapy (BT) or stimulant medication (MED; which also included low dose BT). After 6 months, families whose children still showed at least moderate impairment had access to either treatment for a total of 30 months. Utilization was measured using the number of BT sessions attended and total mg of MED taken over the study period. Families who reported more willingness to use medication for their child’s ADHD at baseline were more likely to use MED and less likely to use BT, regardless of race/ethnicity. Parental knowledge about ADHD was only important in predicting BT utilization for White non-Hispanic families. Greater reduction in ADHD symptoms and impairment significantly predicted more MED utilization for Hispanic families. Results highlight the need to explore multiple parent (e.g., medication willingness) and child (e.g., symptom severity) factors when considering treatment utilization. Results also highlight ethnic differences in which factors affect treatment utilization.

Keywords: ADHD, treatment utilization, race/ethnicity, psychostimulant medication, behavior therapy

ADHD is a highly prevalent, neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Two empirically supported interventions exist for treatment of ADHD in children, behavior therapy (BT) or central nervous system stimulant medication (MED). These interventions are efficacious for families regardless of race/ethnicity, particularly when BT is culturally adapted for racial/ethnic minority families (e.g., Bauermeister & Bernal, 2009; Tamayo et al., 2008). However, for these treatments to be effective, adequate utilization (i.e., amount of treatment received) is imperative (Anderson, Chen, Perrin, & Van Cleave, 2015; Brinkman et al., 2016; Epstein et al., 2017). Research indicates that there are meaningful differences in treatment utilization across racial/ethnic groups. Specifically, for Black non-Hispanic families utilization depends on the type of intervention – Black children are less likely than White children to utilize MED but more likely to utilize BT (Danielson et al., 2018). Hispanic families are less likely than White non-Hispanic families to utilize BT and MED (e.g., Danielson et al., 2018), and both Black non-Hispanic and Hispanic families are less likely than White non-Hispanic families to prematurely terminate BT and MED (e.g., Cummings, Allen, Lally, & Druss, 2017; McCabe, 2002). However, recent research suggests that use of MED are increasing among racial/ethnic minority families, particularly Hispanic families, to rates similar to White non-Hispanic families (Collins & Cleary, 2016; Getahum et al., 2013). Additionally, there is some evidence that differences in treatment utilization across race/ethnicity disappear when sociodemographic variables are taken into consideration (Coker et al., 2009), with evidence that reluctance towards treatments is highest among low-income Spanish-speaking families (Leslie, Plemmons, Monn, & Palinkas, 2007). This indicates that both income and language are important factors in treatment utilization.

Several factors contribute to racial/ethnic discrepancies in treatment of ADHD, including individual and cultural factors (Eiraldi, Mazzuca, Clarke, & Power, 2006). Differences in knowledge of ADHD and treatment preferences are factors potentially influencing treatment utilization. Across ethnicities, greater parental ADHD knowledge is associated with more favorable attitudes about BT and MED and increased usage of BT (Bussing, Schoenberg, & Perwien, 1998; Corkum, Rimer, & Schacher, 1999). Research supports the notion that race/ethnicity moderates parental ADHD knowledge, with White non-Hispanic parents being more likely to believe that ADHD is a medical disorder (McLeod, Fettes, Jensen, Pescosolido, & Martin, 2007). However, parental education and income also moderate parental knowledge, confounding the observed associations with race/ethnicity (Lawton, Gerdes, Haack, & Schneider, 2014). Hispanic cultural values of familism and gender roles are associated with sociological or spiritual etiological beliefs for ADHD rather than biopsychosocial beliefs (Lawton et al., 2014); suggesting Hispanic parents may be less likely to seek medical/psychological services. Instead, they may seek services that fit with their explanation for the problem, such as seeking guidance from a spiritual/religious leader (Yeh et al., 2005). Prior work has produced mixed results as to whether race/ethnicity predicts treatment preference, with some studies finding that ethnic minority families were more likely to view BT positively over MED (Arcia, Fernández, & Jáquez, 2004; McLeod et al., 2007), but others failing to find such a relation (Pham, Goforth, Chun, Castro-Olivo, & Costa, 2017). It is clear that real or perceived barriers may impact treatment utilization. Despite established racial/ethnic differences in utilization and in parental attitudes/knowledge about ADHD, to date no study has examined whether race/ethnicity moderates the relation between parental attitudes and knowledge and actual treatment utilization.

Treatment response is another relevant factor that may be related to treatment utilization. Symptom severity and impairment are important factors to assess as part of an evidence-based assessment for ADHD and to monitor during treatment (Pelham, Fabiano, & Massetti, 2005). Research supports that impairment is related to parent recognition that there is a problem (Bussing et al., 2003) and with help seeking behaviors (Kataoka, Zhang, & Wells, 2002). Therefore, greater impairment translates to more utilization, which has been observed for psychological treatment (Canino et al., 2004; Kataoka et al., 2002). Prior work examining parental preference for treatment of children with ADHD indicates that the majority of parents (70.5%) fall into a “Medication Avoidant” group (treatment decisions based on the desire to avoid using medication for their children), whereas a minority of parents (29.5%) fall into an “Outcome Oriented” group (treatment decisions largely based on a desire for positive treatment outcomes; Waschbusch et al., 2011). Parents in the Outcome Oriented group were more likely to have a lower income, to be more stressed, to be single parents, and to have children who displayed more severe behaviors and impairment. Thus, it is reasonable to expect that greater reductions in symptoms/impairment would be associated with greater utilization and that this may be particularly true for lower income and single parent families (who are disproportionally represented in racial/ethnic minority families). However, to our knowledge, no study to date has examined how changes in symptoms or impairment during treatment are associated with overall utilization, and whether these relations differ by race/ethnicity.

Given these gaps in the literature, the present study examined the role of parental knowledge and attitudes about ADHD and its treatment, and parent perceptions of treatment response in the treatment utilization of families of treatment naïve children with ADHD, and if these relations were moderated by race/ethnicity. The present study constitutes secondary data analysis from a larger randomized controlled trial examining treatment tolerability for pediatric ADHD (see Waxmonsky, Pelham, et al., 2019, for more details). Our dataset is well suited to address these questions, as the study removed many of the common barriers to treatment (cost, childcare, language-barriers) and systematically tracked utilization. As such, the present study holds promise to shed light on potential malleable factors that may influence treatment utilization, and to inform client-centered care should factors differential predict utilization for various racial and ethnic groups (e.g., highlighting treatment improvements to families, adding a psychoeducation component prior to treatment to adjust attitudes/knowledge). It was predicted that families whose parents had greater baseline ADHD knowledge would have higher utilization of BT and MED; whereas, willingness to use either MED or BT was predicted to be associated with higher utilization for the respective treatment. It was further predicted that families who reported lower baseline feasibility concerns for BT would have higher BT utilization. Given theory and research suggesting that lack of ADHD knowledge may result in reduced treatment utilization for racial/ethnic minorities, we predicted that these relations would be stronger for racial/ethnic minorities, particularly Hispanic Spanish-speaking families. Finally, it was predicted that families whose children experienced greater reductions in symptom severity and impairment would have higher utilization of MED and BT, and that these relations would be stronger for racial/ethnic minorities.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Parents of 230 treatment naïve children (168 male) with ADHD (Mage=7.56, SD=1.94) participated in a randomized trial examining the impact of MED on children’s physical growth that employed a BT only arm as a control comparator for growth outcomes (see Waxmonsky, Pelham, et al., for more details). Seventy-four percent of the sample identified as Hispanic (includes individuals of any race who identified as Hispanic), 17% identified as White non-Hispanic, and 9% identified as Black non-Hispanic. Given extensive research supporting differences in treatment utilization among White and Black non-Hispanic families, these groups were examined separately. Families who self-identified as predominately Spanish-speaking during the initial phone screen process had all measures and services (medication visits and BT sessions) administered in Spanish. It was important to examine differences within Hispanic ethnicity based on primary language given evidence that this is a predictor of health outcomes and acculturation (Escobar & Vage, 2000; Rothe, Pumariega, & Sabagh, 2011). This resulted in four racial/ethnic groups in the present study: non-Spanish-speaking Hispanic families (hereafter referred to as Hispanic; n = 144), Spanish-speaking Hispanic families (n = 26), White non-Hispanic families (hereafter referred to as White; n = 40), Black non-Hispanic families (hereafter referred to as Black; n = 21). The majority of parents (85% of mothers, 74% of fathers) had at least some college or technical training. Average caregiver income was $59,585 (SD = 70,637).

Procedure

Participants were recruited through radio advertisements and mailings to schools, primary care providers, and community mental health providers throughout Miami-Dade, and Broward counties. Inclusion criteria included no more than 30 days of prior ADHD medication usage, age 5 to 12, and meeting full diagnostic criteria for any presentation of ADHD. Children with autism spectrum disorder or those using any psychotropic medication were excluded. ADHD was diagnosed using the Disruptive Behavior Disorders Structured Interview (Hartung, McCarthy, Milich, & Martin, 2005), administered by masters-level or higher clinicians, combined with parent and teacher questionnaire ratings (Pelham, Gnagy, Greenslade, & Milich, 1992). Psychiatric comorbidity was assessed by the National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children IV (Shaffer, Fisher, Lucas, Dulcan, & Schwab-Stone, 2000), with comorbid diagnoses allowed if ADHD was the most impairing condition. Diagnoses were confirmed by two MD/PhD faculty members.

At the start of treatment, families were randomly assigned to receive either MED with low dose BT (group-based parent training only, 1 teacher consult/year) or intensive BT (group-based parent training, 3 teacher consults/year, supplemented by individual or additional group sessions as needed) in a 4 to 1 ratio. Data coordinators who were not involved in recruitment constructed the randomization allocation using SAS Proc PLAN. As participants enrolled in the study, the data coordinator assigned ID numbers to the next available randomization code and provided the treatment assignment to the principal investigators in a sealed envelope to be opened at the randomization visit. After 6 months, if children were still displaying moderate impairment or worse (Clinical Global Impression Scale – Severity > 3; Busner & Targum, 2007), they were allowed to cross treatment arms (e.g., BT participants could initiate MED and those in MED could access additional BT treatments). The total study treatment lasted up to 30 months with parents able to choose their treatment modality after month 6 (MED, BT, or both). The only restrictions in medication use after month 6 were on the dose of medication used (capped for those with declining BMI) and the use of weekend medication (restricted for a randomly assigned subset of this with declining BMI).

For both treatment arms, an initial eight session group-based parent training program, Community Parent Education Program (COPE; Cunningham, 2005), was offered with monthly booster sessions. The initial eight session groups were offered to both arms as BT is a recommended and evidenced-based first line treatment option either alone or in combination with MED for children with ADHD (Brown et al., 2005; Zwi, Jones, Thorgaard, York, & Dennis, 2012) and early uptake of BT in relation to MED leads to optimal outcomes (Pelham et al., 2016). For individuals in the BT arm, up to three teacher consults/school year was offered; for individuals in the MED arm, this was only one teacher consult/school year. Individuals in the BT arm could also have up to six individual sessions/year and were free to attend additional more advanced (e.g., problem solving) group sessions offered over the 30 months of the study. Those crossing from MED to BT after month 6 had all restrictions on accessing BT removed. All services were provided free of cost with childcare and evening visits available. All procedures were approved by the Western Institutional Review Board. Written consent was obtained from parents; assent was obtained from children ≥7 years. The sample size of 230 was determined in the larger study to be able to detect small effect sizes.

Measures

ADHD symptoms.

Current ADHD symptoms were assessed using the parent IOWA Conners Rating Scale (IOWA; Loney & Milich, 1982). The IOWA includes five inattentive/overactive items (ADHD symptoms) on a scale from 0 (just a little) to 3 (very much). Items were summed resulting in ADHD symptoms each being out of a total score of 15. The IOWA has good internal consistency and test-retest reliability (Waschbusch & Willoughby, 2008). Cronbach’s alphas for the present sample were .80. Change in ADHD symptoms = endpoint – baseline symptomatology.

Impairment.

The Impairment Rating Scale (IRS; Fabiano et al., 2006) was used to assess overall impairment across several developmentally important areas such relationships with peers and academic progress. For the present study, the overall impairment item (“Overall severity of your child’s problem in functioning and overall need for improvement.”) was used. The reliability and validity of the IRS has been established in several samples, including children with ADHD (Fabiano et al., 2006). Reliability for the present sample was good, α = .92. Change in impairment = endpoint–baseline impairment.

Parent attitudes and knowledge of ADHD and ADHD treatments.

The 43-item ADHD Knowledge and Opinions Scale-Revised (AKOS-R; Bennet, Power, Rostain, & Carr, 1996) was administered to assess parental knowledge of ADHD and attitudes about and feasibility of treatments. Five scales are derived from these items: Knowledge of ADHD (including knowledge of symptoms, characteristics, causes, diagnosis, and treatments of ADHD; e.g., “Most children with ADHD have problems with attention when they become teenagers.”, “ADHD may sometimes be inherited (i.e., passed along in the family).”), Medication Willingness (willingness to use MED; e.g., “I believe medication could help my child with ADHD.”), Counseling Willingness (willingness to attend BT; e.g., “Our family could benefit from counseling sessions to learn how to cope better with our child with ADHD.”), Counseling Feasibility Issues (attitudes about barriers to attend BT; e.g., “I anticipate that scheduling problems would make it difficult for my spouse (if appropriate), my child, and me to arrange counseling appointments.”), and parental competence (ability to handle child’s needs; e.g. “My child’s behavior is so difficult to control that sometimes I feel like a failure as a parent.”). In the present study, we also examined racial/ethnic differences in change in AKOS subscales (Change = endpoint–baseline for respective subscale). Cronbach’s alphas for the present sample ranged from .59 to .78; the parental competence scale, which only consists of three items, had poor reliability and thus was dropped.

Treatment utilization.

BT utilization was measured using the total number of BT sessions attended (group parent sessions, school consultations, individual or booster parent sessions). All but 43 families utilized BT at some point during the study (81%). On average, families utilized a total of 1 school consult (range = 0–7; 112 families), 7 group-therapy sessions (range = 0–48, 180 families), and 1 individual/advanced group session (range = 0–13, 47 families) throughout the course of the study. All MED was provided through the study; the amount of pills dispensed and returned was recorded each visit. Parents also completed a dosing log to record on days MED was taken. Assessment visits occurred at least every 3 months (mean number of assessments = 15.2; SD = 8.1). Logs and pill counts were synchronized at each visit. MED utilization was measured using the total dosage of MED (in mg of methylphenidate equivalents taken throughout the study). Medication was prescribed 7 days a week unless the child was struggling to gain weight. Of all the participants, 167 (73%) used MED at some point in the study.

Analytic Plan

Preliminary analyses explored the descriptive statistics for study variables for each group and bivariate correlations for study variables across groups; effect sizes for mean group differences were calculated using eta-squared (.01 = small, .09 = medium, .25 = large effect). A series of one-way ANOVAs were run in SPSS to explore racial/ethnic differences in predictor and outcome variables. Given prior research (Cummings et al., 2017) that Hispanic and Black youth are more likely than White youth to receive combined treatment, a Chi-square test was run to explore whether rates of combined treatment (attending at least 1 BT session and receiving any MED during the 30 months) differed across races/ethnicity. Finally, we explored if changes in any study variables were significant across race/ethnicity. Next, a series of multiple linear regressions with a multi-categorical moderator were run in SPSS using the PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2017) to explore the role of parent and child factors in predicting treatment utilization, and if such relations were moderated by race/ethnicity. All regression analyses included ADHD symptoms, sibling behavioral/emotional problem status (if any sibling has behavioral or emotional problems), caregiver income, and single parent status as covariates. These are important covariates to include given that each of these factors have been independently linked with treatment knowledge and/or utilization (e.g., Canino et al., 2004; Kataoka et al., 2002; Lindheim & Kolko, 2010; Rieppi et al., 2002).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive statistics, one-way ANOVAs, and follow-up comparisons are reported in Table 1. Effect sizes for all racial/ethnic differences were small to moderate in magnitude. White families had significantly higher incomes at baseline than the other three groups. The distribution of single-parent families at baseline significantly differed across race/ethnicity, χ2 (3)=13.10, p=.004, with White families (8.3%) having less single-parent families than Hispanic (21.3%), Spanish-speaking Hispanic (23.1%), and Black (50%) families. These differences across race/ethnicity support the inclusion of income and single parent status as covariates in analyses.

Table 1.

Exploration of Ethnicity Differences in Parent and Child Attributes and Treatment Utilization

| Variable | Hispanic Families M (SD) n = 143 |

Spanish-speaking Hispanic Families M (SD) n = 26 |

White Families M (SD) n = 40 |

Black Families n = 21 |

F | η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caregiver Income | 55,782 (41,819)a | 26,803 (20,195)a | 102,828 (151,897)b | 45,656 (21,145)a | 5.27** | .08 |

| Baseline Knowledge of ADHD | 8.61 (1.61) | 7.84 (2.44) | 8.89 (1.92) | 7.85 (2.32) | 2.58t | .04 |

| Change in Knowledge of ADHD | −0.27 (2.12) | 0.04 (3.00) | 0.11 (2.11) | −0.50 (2.24) | 0.39 | .01 |

| Baseline Medication Willingness | 21.65 (4.28) | 22.80 (3.97) | 21.04 (2.72) | 20.47 (3.85) | 0.87 | .02 |

| Change in Medication Willingness | 1.96 (4.71) | 0.86 (3.72) | 3.05 (2.82) | 2.00 (3.32) | 0.56 | .02 |

| Baseline Counseling Willingness | 35.15 (4.57) | 35.62 (4.47) | 34.08 (5.79) | 32.53 (4.14) | 2.15t | .03 |

| Change in Counseling Willingness | −4.27 (4.73) | −3.40 (5.85) | −3.33 (4.37) | −5.45 (3.36) | 0.61 | .01 |

| Baseline Counseling Feasibility Issues | 12.28 (2.97)a | 14.57 (2.93)b | 12.23 (2.47)a | 12.55 (3.01) | 2.65t | .06 |

| Change in Counseling Feasibility Issues | −1.04 (3.69) | −1.80 (4.60) | −0.63 (4.13) | −3.75 (2.63) | 0.79 | .03 |

| Baseline ADHD Symptoms | 9.36 (3.26) | 9.17 (2.64) | 9.03 (2.44) | 8.94 (2.88) | 0.17 | .00 |

| Change in ADHD Symptoms | −2.55 (3.76) | −2.43 (3.06) | −2.81 (3.60) | −2.82 (3.63) | 0.08 | .00 |

| Baseline Impairment | 4.69 (1.21) | 4.67 (1.49) | 4.52 (0.96) | 4.76 (1.15) | 0.19 | .00 |

| Change in Impairment | −1.15 (1.80) | −0.61 (1.83) | −1.03 (1.74) | −0.81 (1.77) | 0.73 | .01 |

| Behavior Therapy Sessions | 8.71 (6.89)a | 5.54 (5.77) | 8.73 (10.55)a | 3.65 (3.69)b | 3.87* | .05 |

| Total Study Dosage (in mg) | 11108.11 (7830.52) | 11531.88 (9777.01) | 111944.84 (7665.80) | 8387.63 (7973.63) | 0.69 | .01 |

Note. ADHD = Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Means with different superscript are significantly different from each other.

= p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01.

Examination of change in parent attitudes and knowledge indicated that across races/ethnicities, parents significantly increased in medication willingness (t=−5.16, p< .001) and decreased in counseling feasibility issues (t=2.72, p=.01), but decreased in counseling willingness (t=10.94, p< .001). Additionally, ADHD symptoms and impairment significantly decreased across races/ethnicities (t=10.19 and 8.61, ps< .001, respectively). Bivariate correlations between study variables are presented in Table 2. Income displayed a weak positive correlation with baseline knowledge of ADHD, but a moderate negative correlation with baseline counseling willingness. ADHD symptoms and impairment at baseline displayed weak positive correlations with medication and counseling willingness, and decreases in ADHD symptoms and impairment (a negative change score) were associated with higher baseline medication willingness. A weak positive correlation was found between baseline knowledge of ADHD and BT use; whereas, a moderate positive correlation was found between baseline medication willingness and MED use.

Table 2.

Intercorrelations Between Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Caregiver Income | -- | ||||||||||

| 2. Knowledge of ADHD | .15* | -- | |||||||||

| 3. Medication Willingness | −.06 | .01 | -- | ||||||||

| 4. Counseling Willingness | −.32*** | −.14* | .20* | -- | |||||||

| 5. Counseling Feasibility | −.05 | .03 | .25** | .41*** | -- | ||||||

| 6. ADHD Symptoms | −.11 | −.07 | .24** | .26*** | −.04 | -- | |||||

| 7. Change in ADHD Symptoms | .04 | −.04 | −.28** | −.06 | .01 | −.53*** | -- | ||||

| 8. Impairment | −.15* | −.03 | .26** | .26*** | −.05 | .49*** | −.24** | -- | |||

| 9. Change in Impairment | .02 | −.05 | −.17* | .01 | .17 | −.21** | .51*** | −.49*** | -- | ||

| 10. Behavior Therapy Use | .04 | .17* | −.02 | .16* | .02 | .03 | .01 | −.02 | −.05 | -- | |

| 11. Medication Use | −.03 | −.02 | −.03 | .13 | −.01 | .25** | −.27*** | .28*** | −.17* | .07 | -- |

Note. ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p <.001.

Racial and Ethnic Differences in Treatment Utilization

Descriptive statistics, one-way ANOVAs, and follow-up comparisons are reported in Table 1. White and Hispanic families attended significantly more BT sessions than Black families; however, this difference was no longer significant when income and single-parent status were controlled for, F(3)=2.11, p=.10. There was not a significant difference based on race/ethnicity for use of combined treatment, χ2(3)=3.86, p=.28; as such, utilization of the two treatments were examined separately.

Parental Attitudes and Knowledge about ADHD and its Treatments at Baseline

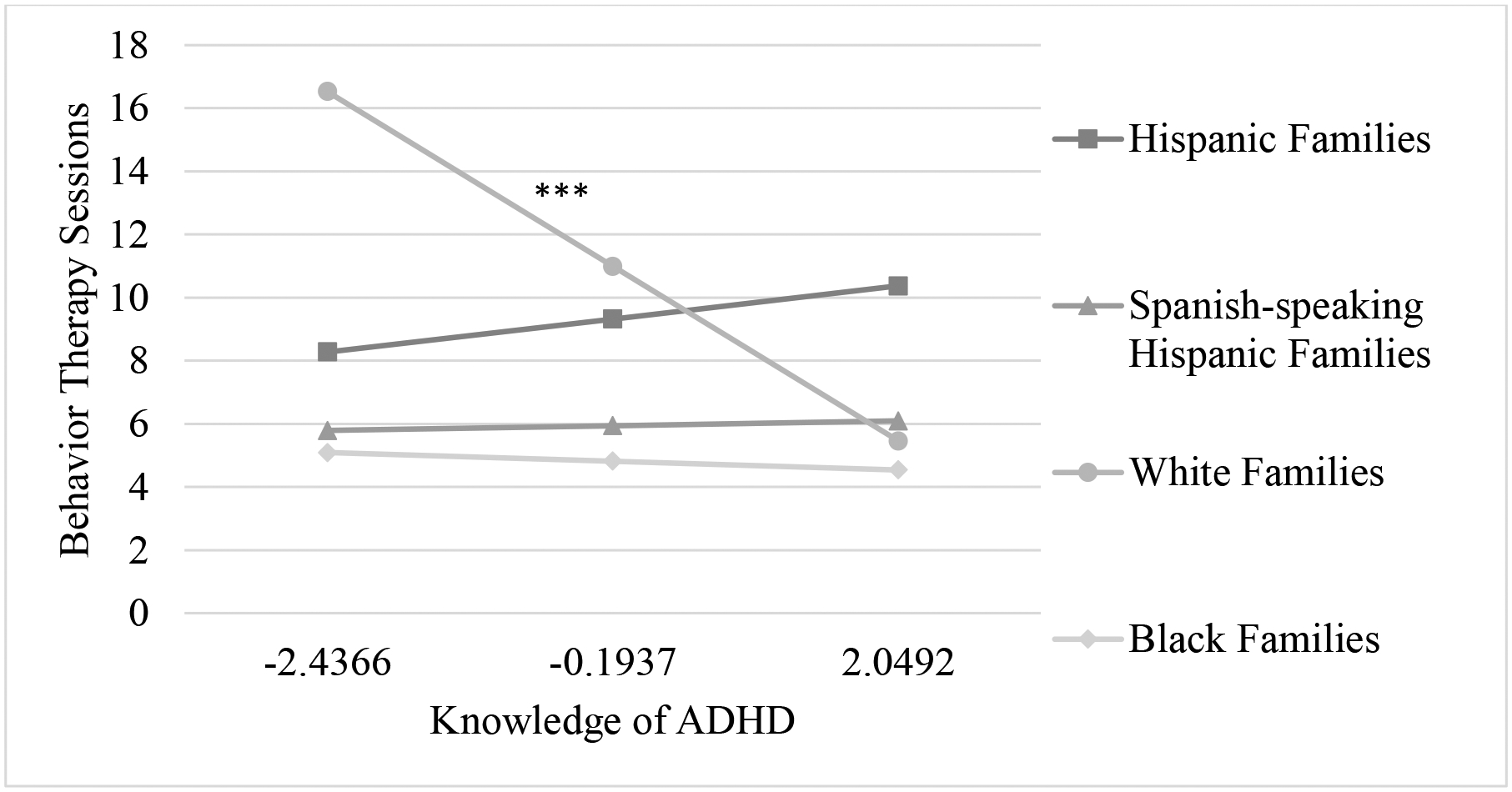

Main effects were found for medication willingness predicting BT utilization (b=−0.43, SE=0.20, p=.03) and MED utilization (b=640.33, SE=242.51, p=.01), such that higher baseline medication willingness was predictive of less BT utilization and more MED utilization throughout the study. Parental knowledge of ADHD significantly interacted with race/ethnicity in predicting BT utilization (b=2.33, SE=0.80, p=.004; Figure 1), such that greater baseline knowledge of ADHD was associated with more BT utilization for White families only (b=2.33, SE=0.69, p=.001). No interactions were found for parental attitudes or knowledge of ADHD variables and MED utilization.

Figure 1.

Interaction between parental knowledge of ADHD and race/ethnicity predicting behavioral therapy utilization. *** p <.001

Change in Child Symptom Severity and Impairment

A change in ADHD symptoms significantly interacted with race/ethnicity in predicting MED utilization (b=−2835.57, SE=1074.02, p=.01; Figure 2a), such that for Hispanic and Spanish-speaking Hispanic families, decreases in ADHD symptoms were associated with higher MED utilization (b=−548.22 SE=210.73, p=.01 and b=−3383.79, SE=1044.94, p=.002, respectively). Similarly, a change in impairment significantly interacted with race/ethnicity in predicting MED utilization (b=−5172.34, SE=2622.07, p=.04; Figure 2b), such that for Spanish-speaking Hispanic families, decreases in impairment were associated with higher MED utilization (b=−5837.71, SE=2579.82, p=.03).

Figure 2.

a) Interaction between change in ADHD symptoms and race/ethnicity predicting medication utilization. b) Interaction between change in Impairment and race/ethnicity predicting med utilization. * p <.05, ** p <.01

Discussion

This study sought to explore differences in treatment utilization across race/ethnicity, when many of the common barriers to treatment were removed (childcare, language, cost), and when important factors like income and single parent status were taken into account. Additionally, this is the first study to our knowledge to explore whether race/ethnicity moderates the relation between parental attitudes/knowledge and treatment utilization, and to examine whether the relation between changes in symptoms/impairment and treatment utilization differ by racial/ethnic group. We found that when many barriers to treatment are removed racial/ethnic minority families are as willing and as likely to use MED as White families, supporting the notion that racial/ethnic differences in MED use may result from barriers to treatment (Eiraldi et al., 2006). Unlike prior work examining the impact of race/ethnicity on ADHD treatment, we were able to examine associations of theorized factors linking race/ethnicity to actual treatment utilization. Parental medication willingness was important for BT (attendance of group therapy, individual therapy, school consultation sessions) and MED (total mg of MED used) utilization regardless of race/ethnicity, with medication willingness significantly increasing throughout the study. Assessing perceptions of medication willingness could help predict treatment utilization, with its malleability suggesting it may be a viable treatment target. Several interactional effects of race/ethnicity were found in predicting treatment utilization, with different factors serving as predictors for different ethnicities. Results highlight the need to explore multiple parent and child factors when considering treatment utilization. These results and their clinical implications are discussed further below.

Racial and Ethnic Differences in Treatment Willingness and Utilization

Results suggest that families who have sought out treatment for their children with ADHD, have largely similar willingness to use BT and MED to treat their children’s ADHD regardless of race/ethnicity. Despite these similarities, differences emerged in BT utilization across groups. Specifically, White and Hispanic families attended significantly more BT sessions than Black families. This stands in contrast to prior work suggesting that Black families utilize more BT than White families (Danielson et al., 2018). However, this difference in BT utilization appeared to be driven by differences in family income and single parent status, as the finding became non-significant when these relevant variables were controlled for. Finally, in contrast to prior research (Danielson et al., 2018), we did not find significant differences between Spanish and non-Spanish-speaking Hispanic families on MED or BT utilization; likewise, income was not correlated with BT or MED utilization. These differential results may have been due to the removal of common barriers in this study.

Role of Parental Attitudes and Knowledge about ADHD and its Treatments in Treatment Utilization

Consistent with our hypotheses, our findings suggest that certain parental factors may be important for families regardless of race/ethnicity. Specifically, parents who entered treatment reporting more willingness to use medication to treat their child’s ADHD used more MED and less BT during the study. Additionally, higher baseline medication willingness was associated with greater declines in counseling willingness and less BT utilization, suggesting that attitudes prior to care influence future attitudes and utilization. Further, and concerningly, although families increased in medication willingness during the study, they decreased in counseling willingness. This is occurred even though every MED assigned family also had access to free BT and 81% of families attended at least 1 session of BT. This inverse association between MED use and future BT use has been observed in other ADHD randomized trials as well as in clinical practice (Pelham et al., 2016; Waxmonsky et al., 2019). Prior studies suggest that MED used secondary to BT results in better outcomes and lower doses of MED than the reverse sequence (Fabiano et al., 2009; Pelham et al., 2016; Pelham & Waschbusch, 1999). Our findings suggest that overall personal experiences with medication treatments can improve parental attitudes about medication, while lowering counseling willingness. As the current study focused on assessing medication tolerability in children, parents enrolling may have been predisposed to use MED. However, children were medication naïve at study entry, so parents would not have had personal experiences with medication for their child. Moreover, this effect has been observed in other trials offering both modalities that less explicitly focused on MED (Pelham et al., 2016). These findings may be a result of MED requiring a lower time commitment and leading to more immediate reductions in visible symptoms than BT (MTA Cooperative Group, 1999). It may also be that parents naturally view ADHD treatments as exclusionary choices.

Besides these main effects, parental knowledge and attitudes only predicted outcomes for White non-Hispanic families, in contrast to our hypotheses. Specifically, for White families, having higher baseline ADHD knowledge was associated with greater BT utilization; however, White parents who experienced greater improvements in ADHD knowledge used less BT during the intervention. Thus, while initial ADHD knowledge makes parents more likely to seek out BT, increases in ADHD knowledge occurring after treatment has started (which often included medication) appears to inhibit BT suggesting that ADHD knowledge should be targeted prior to initiation of medication.

Change in Child Symptom Severity and Impairment in Treatment Utilization

Our findings that changes in ADHD symptoms and impairment predict Hispanic families’ MED utilization is consistent with the notion that Hispanic families may use MED more intermittently rather than being prone to discontinue MED earlier. Specifically, it could be that Hispanic families are more likely to utilize MED only when they see greater symptomatology and clear impairment, which is often centered around academics for youth with ADHD (Daley & Birchwood, 2010). This partially supports prior research suggesting that a small portion of “Outcome Oriented” parents—parents who are more likely to have a lower income, to be more stressed, and to be single parents—make their decisions largely around a desire for positive treatment outcomes, rather than avoidance of medication (Waschbusch et al., 2011). In contrast, this association was not seen for BT, which may be due to lower perceived risks of BT or the challenges with flexibly accessing BT only in times of need. Alternatively, at least for Spanish-speaking Hispanic families, this may have resulted from a floor effect, as 80% of these families attended ≤9 BT sessions.

Although child factors predicted treatment utilization in Hispanic families, no parent factors were related to treatment utilization for Black families. Taken together, results highlight the importance of considering varied factors when targeting utilization among families of different races/ethnicities. Perhaps because ethnic/racial minorities often perceive there to be barriers to treatment (Johnson, Saha, Arbelaez, Beach, & Cooper, 2004; Thompson, Bazile, & Akbar, 2004), even knowledgeable and treatment willing parents may be less likely to utilize available interventions, resulting in these factors being less important. It is also important to highlight that White families started with marginally higher ADHD knowledge and were the racial/ethnic group with the largest increase in knowledge during the intervention. This suggests that for racial/ethnic minorities, efforts aimed at simply improving ADHD knowledge may not impact parent perceptions or desires for treatment; instead, it may be more productive to connect the treatment to observed changes in child behavior.

Limitations

The findings of the present study should be considered within the context of several limitations. First and perhaps most importantly, all treatment was provided through the study with the first 6 months of the study involving restrictions on treatments received. The primary impact of this restriction was on the order of treatments received versus the nature or dose of treatment received. This allowed us to examine the impact of race/ethnicity separate from financial and access constraints. However, results may not generalize to other settings as study administered care has been found to be more effective than community care for pediatric ADHD (MTA Cooperative Group, 1999). Likewise, the motivations and attitudes of these families may be unique to families who are open enough to medication to consider a research study. However, all families had access to BT (with 81% utilizing this intervention), potentially diminishing the impact of this limitation. Additionally, findings may not generalize to locations where Hispanics are not the majority population. Second, the smaller sample sizes in the Spanish-speaking Hispanic, White, and Black groups likely reduced our analytic power and may explain why many group differences that appear to be meaningful are not statistically significant. Third, there is some evidence of differences in parental attitudes about ADHD for mothers versus fathers (Singh, 2003); however, in the present study we were not able to examine parent sex as a possibly relevant factor. Finally, as this study involved secondary analyses of a larger study, we did not have a measure of cultural beliefs or acculturation, which prior research suggests are related to treatment utilization among Hispanic families. However, language is commonly used as a proxy for acculturation (Escobar & Vega, 2000) and this was captured by having a Hispanic and Spanish-speaking Hispanic group.

Recommendations for Clinicians

Based on the findings of the present study, it is recommended that clinicians working with families of children with ADHD assess parental knowledge and attitudes about ADHD and its treatments as part of intake procedures. In particular, for parents who display high willingness towards medication but for whom BT is expected to be beneficial for their child, it will be important to engage in discussions about the benefits of BT before or in conjuncture with MED (Fabiano et al., 2009; Pelham et al., 2016; Pelham & Waschbusch, 1999). Additionally, it is important for clinicians to be aware that for racial/ethnic minorities, solely providing psychoeducation (increasing ADHD knowledge) likely will not impact treatment utilization. Instead, for these families, it will be important for clinicians and medical providers to provide regular feedback to parents on the observed benefits of the treatment.

Conclusion

Findings suggest that when many barriers to treatment are removed, racial/ethnic minority families are as willing to use medication as White families. Parental knowledge appears to be an important factor in treatment utilization for White families; whereas, evidence of improvement in symptoms and impairment emerged as an important factor in treatment utilization for Hispanic families. Together, these findings suggest that as White parents become more familiar with ADHD and its treatments, they may preferentially gravitate towards using MED over BT; whereas, for Hispanic families seeing improvements in functioning is necessary for them to utilize MED for treating ADHD. Parental willingness towards medication to treat their child’s ADHD is an important and potentially malleable variable that impacts MED and BT use, which could easily be measured in clinical care to improve utilization and ultimately, outcomes.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: This trial was funded by the National Institute on Mental Health (R01 MH083692). Funders had no role in the conduct of the research or preparation of the article. Authors also received support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (T32 DA039772, R37 DA009757, UH2 DA041713) and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (F31 AA026768). Some study medication was donated by Janssen Pharmaceuticals. In the past two years, Dr. Waxmonsky has received research funding from NIH, Supernus and Pfizer and served on the advisory board for NLS Pharma and Purdue Pharma. Dr. Pelham has received funding from NIH, NIDA, IES and the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson LE, Chen ML, Perrin JM, & Van Cleave J (2015). Outpatient visits and medication prescribing for US children with mental health conditions. Pediatrics, 136(5), e1178–e1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcia E, Fernández MC, & Jáquez M (2004). Latina mothers’ stances on stimulant medication: Complexity, conflict, and compromise. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 25(5), 311–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauermeister JJ, & Bernal G (2009). Parent‐child interaction therapy for Puerto Rican preschool children with ADHD and behavior problems: A pilot efficacy study. Family Process, 48(2), 232–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DS, Power TJ, Rostain AL, & Carr DE (1996). Parent acceptability and feasibility of ADHD interventions: Assessment, correlates, and predictive validity. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 21(5), 643–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkman WB, Baum R, Kelleher KJ, Peugh J, Gardner W, Lichtenstein P, … & Epstein JN (2016). Relationship between attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder care and medication continuity. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 55(4), 289–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RT, Amler RW, Freeman WS, Perrin JM, Stein MT, Feldman HM, … & Wolraich ML (2005). American Academy of Pediatrics Subcommittee on Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: overview of the evidence. Pediatrics, 115(6), e749–e757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busner J, & Targum SD (2007). The clinical global impressions scale: applying a research tool in clinical practice. Psychiatry (Edgmont), 4(7), 28–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussing R, Schoenberg NE, & Perwien AR (1998). Knowledge and information about ADHD: Evidence of cultural differences among African-American and white parents. Social Science & Medicine, 46(7), 919–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussing R, Zima BT, Gary FA, Mason DM, Leon CE, Sinha K, & Garvan CW (2003). Social networks, caregiver strain, and utilization of mental health services among elementary school students at high risk for ADHD. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 42(7), 842–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canino G, Shrout PE, Rubio-Stipec M, Bird HR, Bravo M, Ramirez R, … & Ribera J (2004). The DSM-IV rates of child and adolescent disorders in Puerto Rico: Prevalence, correlates, service use, and the effects of impairment. Archives of General Psychiatry, 61(1), 85–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker TR, Elliott MN, Kanouse DE, Grunbaum JA, Schwebel DC, Gilliland MJ, … & Schuster MA (2009). Perceived racial/ethnic discrimination among fifth-grade students and its association with mental health. American Journal of Public Health, 99(5), 878–884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins KP, & Cleary SD (2016). Racial and ethnic disparities in parent-reported diagnosis of ADHD: National Survey of Children’s Health (2003, 2007, and 2011). The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 77(1), 52–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corkum P, Rimer P, & Schachar R (1999). Parental knowledge of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and opinions of treatment options: Impact on enrollment and adherence to a 12-month treatment trial. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 44(10), 1043–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings JR, Ji X, Allen L, Lally C, & Druss BG (2017). Racial and ethnic differences in ADHD treatment quality among Medicaid-enrolled youth. Pediatrics, 139(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CE (2005). COPE: Large group, community based, family-centred parent training In Barkley RA (Ed.), Attention Deficit Hyperactivity: A Handbook for Diagnosis and Treatment. New York: Guilford Press [Google Scholar]

- Daley D, & Birchwood J (2010). ADHD and academic performance: Why does ADHD impact on academic performance and what can be done to support ADHD children in the classroom? Child: Care, Health and Development, 36(4), 455–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielson ML, Bitsko RH, Ghandour RM, Holbrook JR, Kogan MD, & Blumberg SJ (2018). Prevalence of parent-reported ADHD diagnosis and associated treatment among US children and adolescents, 2016. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 47(2), 199–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiraldi RB, Mazzuca LB, Clarke AT, & Power TJ (2006). Service utilization among ethnic minority children with ADHD: A model of help-seeking behavior. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 33(5), 607–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein JN, Kelleher KJ, Baum R, Brinkman WB, Peugh J, Gardner W, … & Langberg JM (2017). Specific components of pediatricians’ medication-related care predict attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptom improvement. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 56(6), 483–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar JI, & Vega WA (2000). Mental health and immigration’s AAAs: Where are we and where do we go from here? The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 188(11), 736–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiano GA, Pelham WE Jr, Coles EK, Gnagy EM, Chronis-Tuscano A, & O’Connor BC (2009). A meta-analysis of behavioral treatments for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(2), 129–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiano GA, Pelham WE Jr, Waschbusch DA, Gnagy EM, Lahey BB, Chronis AM, … & Burrows-MacLean L (2006). A practical measure of impairment: Psychometric properties of the impairment rating scale in samples of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and two school-based samples. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 35(3), 369–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getahun D, Jacobsen SJ, Fassett MJ, Chen W, Demissie K, & Rhoads GG (2013). Recent trends in childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. JAMA Pediatrics, 167(3), 282–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartung CM, McCarthy DM, Milich R, & Martin CA (2005). Parent–adolescent agreement on disruptive behavior symptoms: A multitrait-multimethod model. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 27(3), 159–168. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen PS (1999). A 14-month randomized clinical trial of treatment strategies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 56(12), 1073–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RL, Saha S, Arbelaez JJ, Beach MC, & Cooper LA (2004). Racial and ethnic differences in patient perceptions of bias and cultural competence in health care. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 19(2), 101–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka SH, Zhang L, & Wells KB (2002). Unmet need for mental health care among US children: Variation by ethnicity and insurance status. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159(9), 1548–1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton KE, Gerdes AC, Haack LM, & Schneider B (2014). Acculturation, cultural values, and Latino parental beliefs about the etiology of ADHD. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 41(2), 189–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie LK, Plemmons D, Monn AR, & Palinkas LA (2007). Investigating ADHD treatment trajectories: listening to families’ stories about medication use. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 28(3), 179–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindheim O & Kolko DJ (2010). Trajectories of symptom reduction and engagement during treatment for childhood behavior disorders: Differences across settings. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38, 995–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loney JP (1982). Hyperactivity, inattention and aggression in clinical practice. Advances in Behavioral Pediatrics, 2, 113–147. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe KM (2002). Factors that predict premature termination among Mexican-American children in outpatient psychotherapy. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 11(3), 347–359. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod JD, Fettes DL, Jensen PS, Pescosolido BA, & Martin JK (2007). Public knowledge, beliefs, and treatment preferences concerning attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatric Services, 58(5), 626–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MTA Cooperative Group (1999). A 14-month randomized clinical trial of treatment strategies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 56(12), 1073–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE Jr, Fabiano GA, & Massetti GM (2005). Evidence-based assessment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 34(3), 449–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE Jr, Fabiano GA, Waxmonsky JG, Greiner AR, Gnagy EM, Pelham III WE, … & Karch K (2016). Treatment sequencing for childhood ADHD: A multiple-randomization study of adaptive medication and behavioral interventions. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 45(4), 396–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE Jr, Gnagy EM, Greenslade KE, & Milich R (1992). Teacher ratings of DSM-III-R symptoms for the disruptive behavior disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 31(2), 210–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE, & Waschbusch DA (1999). Behavioral intervention in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder In Handbook of disruptive behavior disorders (pp. 255–278). Springer, Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Pham AV, Goforth AN, Chun H, Castro-Olivo S, & Costa A (2017). Acculturation and Help-Seeking Behavior in Consultation: A Sociocultural Framework for Mental Health Service. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 27(3), 271–288. [Google Scholar]

- Pham AV, Goforth AN, Chun H, Castro-Olivo S, & Costa A (2017). Acculturation and Help-Seeking Behavior in Consultation: A Sociocultural Framework for Mental Health Service. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 27(3), 271–288. [Google Scholar]

- Rieppi R, Greenhill LL, Ford RE, Chuang S, Wu M, Davies M, & Hechtman L (2002). Socioeconomic status as a moderator of ADHD treatment outcomes. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 41, 269–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothe E, J Pumariega A, & Sabagh D (2011). Identity and acculturation in immigrant and second generation adolescents. Adolescent Psychiatry, 1(1), 72–81. [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, Dulcan MK, & Schwab-Stone ME (2000). NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 39(1), 28–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh I (2003). Boys will be boys: Fathers’ perspectives on ADHD symptoms, diagnosis, and drug treatment. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 11(6), 308–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamayo JM, Pumariega A, Rothe EM, Kelsey D, Allen AJ, Vélez-Borrás J, … & Durell TM (2008). Latino versus Caucasian response to atomoxetine in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 18(1), 44–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson VLS, Bazile A, & Akbar M (2004). African Americans’ perceptions of psychotherapy and psychotherapists. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 35(1), 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Waschbusch DA, Cunningham CE, Pelham WE Jr, Rimas HL, Greiner AR, Gnagy EM, … & Scime M (2011). A discrete choice conjoint experiment to evaluate parent preferences for treatment of young, medication naive children with ADHD. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 40(4), 546–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waschbusch DA, & Willoughby MT (2008). Parent and teacher ratings on the IOWA Conners Rating Scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 30(3), 180–192. [Google Scholar]

- Waxmonsky JG, Baweja R, Liu G, Waschbusch DA, Fogel B, Leslie D, & Pelham WE Jr (2019). A Commercial Insurance Claims Analysis of Correlates of Behavioral Therapy Use Among Children With ADHD Psychiatric Services, Advanced Online Publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh M, McCabe K, Hough RL, Lau A, Fakhry F, & Garland A (2005). Why bother with beliefs? Examining relationships between race/ethnicity, parental beliefs about causes of child problems, and mental health service use. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(5), 800–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwi M, Jones H, Thorgaard C, York A, & Dennis JA (2012). Parent training interventions for attention deficity hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children aged 5 to 18 years. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 8(1), 1–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]