Abstract

Background

Progressive disseminated histoplasmosis (PDH) is a serious fungal infection that affects people living with HIV. The best way to treat the condition is unclear.

Objectives

We assessed evidence in three areas of equipoise.

1. Induction. To compare efficacy and safety of initial therapy with liposomal amphotericin B versus initial therapy with alternative antifungals.

2. Maintenance. To compare efficacy and safety of maintenance therapy with 12 months of oral antifungal treatment with shorter durations of maintenance therapy.

3. Antiretroviral therapy (ART). To compare the outcomes of early initiation versus delayed initiation of ART.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group Specialized Register; Cochrane CENTRAL; MEDLINE (PubMed); Embase (Ovid); Science Citation Index Expanded, Conference Proceedings Citation Index‐Science, and BIOSIS Previews (all three in the Web of Science); the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, ClinicalTrials.gov, and the ISRCTN registry, all up to 20 March 2020.

Selection criteria

We evaluated studies assessing the use of liposomal amphotericin B and alternative antifungals for induction therapy; studies assessing the duration of antifungals for maintenance therapy; and studies assessing the timing of ART. We included randomized controlled trials (RCT), single‐arm trials, prospective cohort studies, and single‐arm cohort studies.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors assessed eligibility and risk of bias, extracted data, and assessed certainty of evidence. We used the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool to assess risk of bias in randomized studies, and ROBINS‐I tool to assess risk of bias in non‐randomized studies. We summarized dichotomous outcomes using risk ratios (RRs), with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Main results

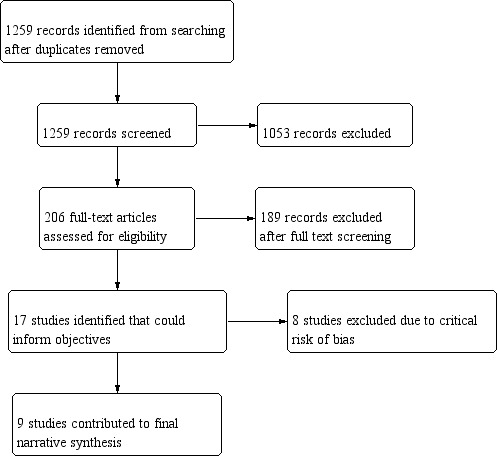

We identified 17 individual studies. We judged eight studies to be at critical risk of bias, and removed these from the analysis.

1. Induction

We found one RCT which compared liposomal amphotericin B to deoxycholate amphotericin B. Compared to deoxycholate amphotericin B, liposomal amphotericin B may have higher clinical success rates (RR 1.46, 95% CI 1.01 to 2.11; 1 study, 80 participants; low‐certainty evidence). Compared to deoxycholate amphotericin B, liposomal amphotericin B has lower rates of nephrotoxicity (RR 0.25, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.67; 1 study, 77 participants; high‐certainty evidence). We found very low‐certainty evidence to inform comparisons between amphotericin B formulations and azoles for induction therapy.

2. Maintenance

We found no eligible study that compared less than 12 months of oral antifungal treatment to 12 months or greater for maintenance therapy.

For both induction and maintenance, fluconazole performed poorly in comparison to other azoles.

3. ART

We found one study, in which one out of seven participants in the 'early' arm and none of the three participants in the 'late' arm died.

Authors' conclusions

Liposomal amphotericin B appears to be a better choice compared to deoxycholate amphotericin B for treating PDH in people with HIV; and fluconazole performed poorly compared to other azoles. Other treatment choices for induction, maintenance, and when to start ART have no evidence, or very low certainty evidence. PDH needs prospective comparative trials to help inform clinical decisions.

Plain language summary

How best to treat progressive disseminated histoplasmosis in people with HIV

What was the aim of this review?

The aim of this Cochrane Review was to investigate some treatment dilemmas with progressive disseminated histoplasmosis in people living with HIV. We collected and analysed all relevant studies to answer this question and found 17 studies.

Key messages

Liposomal amphotericin B may improve clinical success compared to deoxycholate amphotericin B when starting treatment.

Liposomal amphotericin B results in less kidney damage compared to deoxycholate amphotericin B when starting treatment.

We are unsure how long people should stay on treatment after they have successfully completed the starting stage. We are unsure at what time during treatment of the fungal infection it is best to start treatment to fight the HIV virus.

What was studied in this review?

Histoplasmosis is an infection caused by inhaling a fungus called Histoplasma. The most severe form of histoplasmosis is called progressive disseminated histoplasmosis, in which the infection spreads from the lungs to other organs. It is life‐threatening for people with advanced HIV.

The treatment of progressive disseminated histoplasmosis starts with 'induction', in which medicines are started to rapidly attack the fungus. The next phase is called 'maintenance', in which medicines are used to prevent the fungus taking hold again. During treatment of the fungus, antiretroviral medicines are started to fight the HIV virus.

We wanted to find out the best induction treatment, if maintenance could be for less than one year, and when was the best time to start antiretroviral medicines.

What are the main results of the review?

We found 17 studies. We removed eight from the review as they did not include important measurements that might change results. These included how severe the HIV infection was, or if the patients had other infections at the same time.

One study compared two forms of the same medicine for starting treatment of histoplasmosis, liposomal amphotericin B and deoxycholate amphotericin B. It found that the more expensive liposomal form is less likely to cause kidney damage and may have higher clinical success rates than the deoxycholate form.

None of the studies looked at whether maintenance could be less than one year. Two studies looked a antiretroviral medicines, but we do not know when it is best to start them.

How up to date is the review?

We searched for studies that had been published up to 20 March 2020.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Induction: liposomal amphotericin compared with amphotericin deoxycholate.

| Liposomal amphotericin compared with amphotericin deoxycholate for induction therapy of progressive disseminated histoplasmosis | ||||||

|

Patient or population: adults with HIV and progressive disseminated histoplasmosis Settings: endemic areas Intervention: induction therapy with liposomal amphotericin B Comparison: amphotericin B deoxycholate | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| dAmB | lAmB | |||||

| Clinical success | 560 per 1000 | 818 per 1000 (566 to 1000) | RR 1.46 (1.01 to 2.11) | 80 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa | Compared to dAmB, lAmB may have higher clinical success rates. |

| Death | 125 per 1000 | 19 per 1000 (3 to 173) | RR 0.15 (0.02 to 1.38) | 77 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb |

Treatment with lAmB may result in lower mortality than treatment with dAmB. |

| Safety outcomes: nephrotoxicity | 375 per 1000 | 94 per 1000 (34 to 251) | RR 0.25 (0.09 to 0.67) | 77 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High |

Treatment with lAmB resulted in lower rates of nephrotoxicity compared to treatment with dAmB; this was supported by findings of a Cochrane Review which reported moderate‐certainty evidence (Botero Aguirre 2015). |

| Safety outcomes: drug discontinuation | 83 per 1000 | 19 per 1000 (2 to 198) | RR 0.23 (0.02 to 2.38) | 77 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowc | We do not know if treatment with lAmB leads to fewer treatment discontinuations than dAmB. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; dAmB: deoxycholate amphotericin B; lAmB: liposomal amphotericin B; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate certainty: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low certainty: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low certainty: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aDowngraded two levels for very serious imprecision: the CI met the line of no effect and was based on very few events (73 participants, 1 randomized controlled trial). bDowngraded two levels for very serious imprecision: the CIs were wide and crossed the line of no effect. cDowngraded one level for serious risk of bias (due to unclear reporting criteria) and two levels for very serious imprecision (the CIs were wide and crossed the line of no effect).

Background

Description of the condition

Progressive disseminated histoplasmosis (PDH) is an important infectious disease among people living with HIV. PDH is one of the endemic mycoses, meaning a fungal infection localized to a specific region. It is caused by two human pathogens, Histoplasma capsulatum var. capsulatum (in the Americas) and Histoplasma capsulatum var. duboisii (in Africa). It causes severe morbidity and carries a risk of mortality of over 60% (Adenis 2014; Cano‐Torres 2019). H capsulatum var. capsulatum has historically been thought of as predominantly effecting the Americas, but there is evidence of a wider global distribution (Baker 2019).

The diagnosis of PDH in people living with HIV is usually made based on:

risk factors for the disease (advanced HIV);

clinical manifestations consistent with disseminated histoplasmosis, such as fever, fatigue, weight loss, and hepatosplenomegaly;

histoplasma antigen assays;

microscopic demonstration or isolation of Histoplasma from extrapulmonary sites; due to slow growth, isolation is likely to be too slow to allow diagnosis.

Description of the intervention

The current standard of care for PDH is typically based on Infectious Diseases Society of America 2007 guidelines (Wheat 2007). This guideline recommends:

for moderately severe to severe disease, liposomal amphotericin B (3.0 mg/kg daily for 1 to 2 weeks), followed by oral itraconazole (200 mg 3 times daily for 3 days and then 200 mg twice daily for a total of at least 12 months);

for mild‐to‐moderate disease, itraconazole (200 mg 3 times daily for 3 days), and then twice daily for at least 12 months.

Alongside treatment of PDH, HIV is treated with antiretroviral therapy (ART). Commencing ART might rapidly restore immune function. This may cause an excessive inflammatory response known as immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) (Melzani 2020).

How the intervention might work

Azoles inhibit biosynthesis of ergosterol, which is essential in fungal cell membranes. Itraconazole, voriconazole, and posiconazole are thought to be fungicidal for histoplasma, but fluconazole is thought to have fungistatic activity only. Polyenes, such as amphotericin B, bind to fungal membrane sterols and disrupt cell membranes. They are thought to have fungicidal activity. Non‐randomized trial data from animal studies suggest that near maximal antifungal activity with amphotericin B occurs within three days, which has led to interest in shorter courses in treatment of other mycoses, such as cryptococcal meningitis (Tenforde 2018).

Why it is important to do this review

Currently available guidelines for management of PDH date from 2007. These were designed for use by clinicians in the USA, a high‐resource country. The advent of widespread availability of ART internationally has changed treatment paradigms for HIV. In resource‐limited settings, there is interest in revisiting the optimal treatment options for PDH. This review summarizes available evidence, and in particular we aimed to understand if new evidence could inform updated international guidelines on PDH.

Objectives

1. Induction. To compare efficacy and safety of initial therapy with liposomal amphotericin B versus initial therapy with alternative antifungals.

2. Maintenance. To compare efficacy and safety of maintenance therapy with 12 months of oral antifungal treatment with shorter durations of maintenance therapy. (Please note, itraconazole is a preferred oral antifungal agent, see results.)

3. Antiretroviral therapy (ART). To compare the outcomes of early initiation of ART versus delayed initiation of ART.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We planned to synthesize the study types in order of priority. At each stage, if we found a sufficient number of studies to allow a high‐certainty synthesis, we did not intend to progress further. As we did not find sufficient evidence to allow high‐certainty synthesis, our review includes the following study types:

randomized controlled trials (RCTs);

quasi‐RCTs/non‐RCTs;

prospective cohort studies;

retrospective cohort studies;

single arm cohort studies.

We excluded case reports and case series.

Types of participants

HIV‐positive children, adolescents, and adults with a clinical diagnosis of PDH.

Types of interventions

We aimed to make the following comparisons.

| Objective | Intervention | Comparisons |

| 1. Induction | Liposomal amphotericin B (3.0 mg/kg daily) for 1–2 weeks | Lipid complex amphotericin B Deoxycholate amphotericin B Other antifungal agents |

| 2. Maintenance | Oral antifungal treatment for < 12 months | Oral antifungal treatment for ≥ 12 months |

| 3. ART | Early initiation (within 4 weeks of commencing antifungal therapy) | Delayed initiation (> 4 weeks after starting antifungal treatment) |

Types of outcome measures

We collected data on key outcomes, as summarized in the table below.

| Objective | Efficacy outcomes of interest | Safety outcomes of interest |

| 1. Induction | Clinical failure at or before study end Laboratory failure at or before study end |

Toxicity Early discontinuation |

| 2. Maintenance | Relapse of histoplasmosis at 12 months, or other clinically important time points All‐cause mortality at 12 months |

Toxicity Early discontinuation |

| 3. ART | Incidence of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome Viral failure |

Toxicity Early discontinuation |

Where possible, we collected dichotomous and time‐to‐event data for relevant outcomes. We also collected data on mortality, and severe adverse events, including type and frequency.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We developed our search strategy with the assistance of the Information Specialist, Vittoria Lutje. We searched the following databases on 20 March 2020 using the search terms and strategy described in Appendix 1: Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group Specialized Register; Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2020, Issue 3, published in the Cochrane Library); MEDLINE (PubMed, from 1966); Embase (Ovid, from 1947); Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI‐EXPANDED, from 1900), Conference Proceedings Citation Index‐Science (CPCI‐S, from 1900), and BIOSIS Previews (from 1926) (all three using the Web of Science platform). We also searched the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (www.who.int/ictrp/search/en/), ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov/), and the ISRCTN registry (www.isrctn.com/) to identify ongoing studies.

Searching other resources

We examined reference lists of relevant studies and reviews.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (MM and PH) screened the titles and abstracts of the search results to determine eligibility using Covidence (www.covidence.org/). We did not perform double screening as we prepared the review rapidly to inform a guidelines meeting. We each assessed a random sample of the other author's screening. There were no disagreements. Both review authors screened the full texts of potentially eligible studies, and resolved any disagreement by discussion. At the time of full‐text screening, we categorized the studies by study design.

Data extraction and management

One review author (PH) extracted data, and one review author (MM) reviewed all data extraction to ensure accuracy.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

For each included study, both review authors performed a risk of bias assessment resolving any disagreements through discussion. We used the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool for RCTs. For non‐randomized studies, we used the Risk of Bias In Non‐Randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS‐I) tool. We developed a theoretical target study and assessed each non‐randomized study across up to seven domains. Each assessment was discontinued if a domain was deemed to be at critical risk of bias. Each outcome was assessed. We identified relevant confounding factors through investigation of the literature and in discussion with expert clinicians. These a priori factors included severity of disease (histoplasmosis and CD4 count); time to treatment; and, for objectives 2 and 3, adherence to ART/maintenance therapy for histoplasmosis.

Data synthesis

Narrative synthesis

We followed narrative synthesis methodology (Popay 2006). Within this synthesis, we organized findings from included studies to describe patterns across the studies in terms of the:

direction of effects;

size of effects.

We calculated 95% confidence intervals (CI) for binomial proportions. We calculated 95% CIs for risk ratios (RR) using Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2014). Studies assessed as at critical risk of bias were excluded from narrative synthesis.

Quantitative synthesis

We did not identify trials that were sufficiently similar in design or outcomes to allow a meaningful meta‐analysis of outcome data. Therefore, we have not performed quantitative synthesis.

Exploring relationships in the data

We planned to explore relationships to consider the factors that might explain any differences in direction and size of effect across the included studies. For data included in narrative synthesis, we explored relationships using textual descriptions of key study elements (see Characteristics of included studies table), groupings and clusters of similar studies, and presentation of findings in tabulated form.

Assessing the certainty of our conclusions

We planned to present adapted GRADE tables to summarize the certainty of our findings for each outcome. As we did not find good evidence to answer all objectives, we presented a GRADE table for outcomes relevant to 'Objective 1. Induction' detailing certainty of findings. We could not include any studies to answer 'Objective 2. Maintenance', so presented a narrative summary of indirect evidence in the body of the review only. We presented an additional summary table for 'Objective 3. ART'.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

We retrieved 1259 results from our electronic search. After title and abstract screening, we identified 206 reports for full‐text screening. Following full‐text screening, we identified 16 individual studies which were relevant to the review. These included:

two RCTs (ACTG‐A5164, 2009; Johnson 2002);

four single arm trials (ACTG084, 1992; ACTG120, 1992; ACTG174, 1994; McKinsey 1989);

four prospective cohort studies (Baddley 2008; Couppié 2004; Goldman 2004; Ramdial 2002);

six retrospective cohort studies (Luckett 2015; Mootsikapun 2006; Myint 2014; Negroni 2017; Norris 1994; Pietrobon 2004).

We have shown the results of our search in Figure 1.

1.

Review flow diagram.

We found one additional unpublished retrospective cohort study via correspondence with authors (Melzani 2020).

Therefore, there were 17 individual studies. We excluded eight of these studies from analysis as we assessed them to be at critical risk of bias using ROBINS‐I methodology (Table 2). We listed these below.

1. Table of studies at critical risk of bias overall (ROBINS‐I): disease‐related outcomes.

| Studies at critical risk of bias outcomes: death, relapse of histoplasmosis | |||

| Study | Review objective | Domain | Comment |

| McKinsey 1989 | 1 and 2 | Confounding | Confounding domains were not controlled for. No report of ART use, CD4 counts, or clinical condition of participants. Rationale for selection of treatment regimen not described. |

| Couppié 2004 | 1 | Participant selection | Selection of intervention was made by the treating physician. As more severely ill participants were more likely to get AmB than ITRA selection was strongly related to the outcome. |

| Ramdial 2002 | 1 | Confounding | Confounders not addressed with respect to treatment regimens. Descriptive account provided of management of participants without detail on severity of conditions, comedications, or comorbidities. No information provided on time to treatment or duration of treatment. |

| Baddley 2008 | 2 | Confounding | Logistic regression used to determine association of variables with mortality including potential confounders, age, and race. Antifungal treatment data were not included in regression or reported in detail per participant. Authors reported 32/41 participants received ITRA, 22/41 dAmB, and 7/41 lAmB. Switches between medications were not reported. Authors reported 29 participants received ITRA after AmB. Denominator not reported. 8/13 participants who died were receiving an AmB preparation and 5/13 receiving ITRA. Time of transition from AmB to azole not reported. |

| Myint 2014 | 2 | Confounding | Physician determined discontinuation of maintenance therapy may have been influenced by prognostic factors that were not controlled for. Multiple logistic regression used to determine variables associated with relapse; however, assignment to treatment arms were based on clinical assessment and viral load. 'Adherence to therapy' not defined. Unclear if this referred to ART, ITRA, or both. No evidence of adjustment for time‐varying confounding. |

| Negroni 2017 | 2 | Confounding | Comorbidity and comedications were not reported or controlled for. Outcome data were not linked to disease severity. Outcomes not reported by drug regimen. Treatment regimens varied by drug and duration. There were drug switches. |

| Norris 1994 | 2 | Confounding | Authors reported no specific criteria to select participants for intervention. Criteria included unavailability of ITRA and preference for oral therapy. Intervention group determined by treating physicians who also evaluated clinical evidence of relapse and side effects. Severity of HIV, comorbidities and comedication were not reported. |

| Pietrobon 2004 | 2 | Confounding |

For outcome 'relapse of histoplasmosis': follow‐up periods not reported. Duration of ITRA or FCN not reported. Switches between regimens not reported. Concurrent medication not reported. No statistical methods to control for confounding reported. For outcome 'death': this study can be considered to be at 'serious risk of bias'. No use of ART during treatment period. Comorbidities mentioned but unclear whether all relevant co morbidities studied. Severity of PDH not reported. No report of statistical methods to control for confounders. ≥ 1 known important domain was not appropriately measured or controlled for. Given the very small numbers, we have not reported further details in synthesis. |

For details of risk of bias assessments see Appendix 3.

AmB: amphotericin B; ART: antiretroviral therapy; dAmB: deoxycholate amphotericin B; FCN: fluconazole; ITRA: itraconazole; lAmB: liposomal amphotericin B.

Included studies

1. Induction

From our search, the studies that gave information about relevant outcomes for induction therapies included:

one RCT (Johnson 2002);

two single arm trials (ACTG120, 1992; ACTG174, 1994);

one retrospective cohort study (Luckett 2015).

The following studies were excluded from narrative synthesis as they were at critical risk of bias using ROBINS‐I methodology.

one single arm trial (McKinsey 1989);

two prospective cohort studies (Couppié 2004; Ramdial 2002).

2. Maintenance

From our search, the studies that gave information about relevant outcomes for maintenance therapies included:

three single arm trials (ACTG084, 1992; ACTG120, 1992; ACTG174, 1994);

one prospective cohort study (Goldman 2004);

one retrospective cohort study (Mootsikapun 2006).

The following studies were excluded from narrative synthesis as they were at critical risk of bias using ROBINS‐I methodology:

one single arm trial (McKinsey 1989);

one prospective cohort study (Baddley 2008);

four retrospective cohort studies (Myint 2014; Negroni 2017; Norris 1994; Pietrobon 2004).

3. ART

We found one RCT which helped inform decisions regarding ART (ACTG‐A5164, 2009). We included Melzani 2020 in a narrative synthesis as it provided evidence of baseline risk, but could not directly inform the objective.

Excluded studies

We excluded 186 studies (including an RCT, single arm trials, prospective cohort studies, and retrospective cohort studies) after full‐text review. In the majority of cases, we were unable to extract relevant data from the study reports. We reported reasons for exclusion for a sample of 34 references in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Risk of bias in included studies

For the two randomized studies, risk of bias was low (Johnson 2002 shown in Table 3; ACTG‐A5164, 2009 shown in Table 4). These are summarized in Figure 2.

2. Risk of bias Johnson 2002.

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation | Unclear risk | Authors reported randomizations in blocks. Details of method of randomization not provided |

| Allocation concealment | Low risk | Closed envelopes |

| Blinding of participants and personnel | Low risk | Authors reported that participants received the intervention and comparator by intravenous infusion "in a blinded fashion". It is possible that both participants and personnel were blinded. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment | Low risk | Clinical and mycological outcomes were predetermined. These included objective components including temperature and laboratory findings. |

| Incomplete outcome data | Low risk | Reasons reported for missing data. Proportion of data missing from each group was similar. |

| Selective reporting | Low risk | No protocol cited; however, reported outcomes are consistent with trial aims. |

3. Risk of bias ACTG‐A5164, 2009.

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation | Low | Random sequence was generated by central computer using permuted blocks within strata. Neither block size nor treatment assignments to other sites were public. |

| Allocation concealment | Unclear | No details provided in protocol or included study. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel | High | Protocol stated that for arm B (deferred ART), no study‐provided drugs were to be provided initially hence blinding of participants and personnel was not possible. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment | Low | Primary outcome was a composite endpoint of survival and viral load. Detection bias was unlikely. |

| Incomplete outcome data | Low | Equal numbers withdrew without primary endpoint data in each study arm. Details provided for these participants. |

| Selective reporting | Low | Reported outcomes were consistent with protocol. |

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included randomized study.

For the remaining 15 non‐randomized studies, we assessed eight to be at critical risk of bias using ROBINS‐I, and excluded these from synthesis as described above (Table 2). The remaining seven non‐randomized studies were at serious risk of bias using ROBINS‐I (Table 5). One study was at critical risk of bias for the relapse outcome, and serious risk of bias for the mortality outcome (Pietrobon 2004). We excluded this study from synthesis as the mortality outcome did not sufficiently inform the objective.

4. Table of studies at serious risk of bias overall (ROBINS‐I): disease‐related outcomes.

| Studies at serious risk of bias outcomes: death, relapse of histoplasmosis | |||

| Study | Review objective | Domain(s) | Comment |

| ACTG120, 1992 | 1 and 2 | Confounding; participant selection; intervention classification | Severity of HIV; severity of PDH and comorbidities were not controlled for using appropriate statistical methodology. ART use at baseline of an earlier phase of the trial reported: those who responded to the intervention (ITRA) in the induction phase were selected for the intervention in the maintenance phase: participants started intervention at various doses and had reductions in dose made at variable intervals. While this was likely to have been informed by ITRA blood levels that were being monitored, detailed data were not provided per participant. |

| ACTG174, 1994 | 1 and 2 | Confounding; participant selection | At 3 months, protocol was revised and treatment regimen amended. Analyses were performed on participants who received the revised protocol (higher doses of FCN). Severity and management of HIV was not reported or controlled with appropriate statistical methods: selection into the maintenance arm of the study was related to the effect of the intervention in the induction phase. |

| Luckett 2015 | 1 | Intervention classification; outcome measurement | No information about dose, frequency, and timing of interventions. Information was collected retrospectively. Treatment failure outcome was based on clinician judgement only. This was likely to favour switch from azole to amphotericin. |

| ACTG084, 1992 | 2 | Confounding | Severity of HIV infection and ART use were not controlled for with appropriate statistical methods. |

| Goldman 2004 | 2 | Participant selection | Start of intervention varied – participants enrolled after a range of 14–81 months of antifungal therapy. Unclear how many eligible people were not enrolled. |

| Mootsikapun 2006 | 2 | Confounding; participant selection | ≥ 1 known important domain was not appropriately measured or controlled for: details of disease severity, comedications and comorbidities not provided for 27 participants discharged from hospital: maintenance therapy was commenced in those who responded to initial treatment on amphotericin B. Timing of start of maintenance therapy was not reported. Selection into this part of the study was related to the intervention. |

| Melzani 2020 | 3 | Confounding | ART was discontinued in 2/22 participants at the physician's decision; 2/22 due to patient choice. In unmasking group (14 participants), 10/14 received lAmB and 4/14 received ITRA. Paradoxical group (8 participants) physicians continued ART and ITRA for 6/8. Rationale for treatment choices not reported. Appropriate statistical measures to control for confounding were not reported. ≥ 1 known important domain was not appropriately measured or controlled for. |

For details of risk of bias assessment see Appendix 3.

ART: antiretroviral therapy; FCN: fluconazole; ITRA: itraconazole; lAmB: liposomal amphotericin B; PDH: progressive disseminated histoplasmosis.

Risk of bias was low in both included randomized studies (Table 3; Table 4; Figure 2). Eight non‐randomized studies were at critical risk of bias and eight at serious risk of bias overall using ROBINS‐I. Details on assessment by outcome are provided in Table 2 and Table 5. Detailed domain assessments are available in Appendix 2.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

1. Induction therapy for progressive disseminated histoplasmosis

Liposomal amphotericin B compared to deoxycholate amphotericin B

One RCT compared liposomal amphotericin B and deoxycholate amphotericin B (Johnson 2002). There was greater treatment success with liposomal amphotericin B compared to deoxycholate amphotericin B (RR 1.46, 95% CI 1.01 to 2.11; 1 trial, 80 participants; Analysis 1.1). There were three deaths in the deoxycholate amphotericin B arm and one death in the liposomal amphotericin B arm (RR 0.15, 95% CI 0.02 to 1.38; 1 trial, 77 participants; Analysis 1.2). There were lower rates of nephrotoxicity (defined as creatinine greater than twice the upper limit of normal) with liposomal amphotericin B than with deoxycholate amphotericin B (RR 0.25, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.67; 1 trial, 77 participants; Analysis 1.3). The authors did not report other safety data, including frequencies of commonly reported toxicities such as anaemia.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Liposomal amphotericin B (lAmB) versus deoxycholate amphotericin B (dAmB), Outcome 1: Clinical success

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Liposomal amphotericin B (lAmB) versus deoxycholate amphotericin B (dAmB), Outcome 2: Death

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Liposomal amphotericin B (lAmB) versus deoxycholate amphotericin B (dAmB), Outcome 3: Safety outcomes

Liposomal amphotericin B compared to other antifungals

No RCTs compared liposomal amphotericin B to other antifungals.

One retrospective cohort study compared all forms of amphotericin B to triazole therapy (including itraconazole, posaconazole, and voriconazole) (Luckett 2015). Treatment success for triazoles was 83% (95% CI 62% to 95%). The report did not disaggregate data by disease severity, but reported that across the study (which included people who were immunocompromised for reasons other than HIV infection), frequency of triazole failure was similar among people with severe infection compared with those with mild‐to‐moderate infection.

Deoxycholate amphotericin B compared to other antifungals

No study compared deoxycholate amphotericin B to other antifungals.

Treatment success rates for other antifungals

In the absence of comparative studies, we reported treatment success rates for antifungal agents (see 'Narrative results table 1').

Itraconazole

One single arm trial of itraconazole in mild‐to‐moderate PDH reported a treatment success rate of 85% (95% CI 73% to 93%; 1 study, 50/59 participants) at a dose of 300 mg twice daily for three days then 200 mg twice daily for 12 weeks (ACTG120, 1992).

Fluconazole

One single arm trial of fluconazole reported a treatment success rate of 74% (95% CI 59% to 85%; 1 study, 36 successes of 49 participants), at a dose of 1600 mg on day one, then 800 mg once daily for 12 weeks (ACTG174, 1994). This study initially reported a treatment success rate of 80% (95% CI 56% to 94%; 16 successes of 20 participants) for fluconazole 1600 mg on day one followed by 600 mg once daily for eight weeks. However, the protocol was intensified when relapse was subsequently observed in 6/16 participants (37.5%, 95% CI 15% to 64%).

Narrative results: table 1: induction therapy

| Study | Method | Participants | Interventions | Primary outcome(s) | Setting | Disease severity | Overall risk of bias | Narrative of efficacy findings (95% CIs) | Narrative of safety findings |

| ACTG120, 1992 | Single arm trial | 59 with PDH | ITRA 300 mg BD for 3 days then 200 mg BD for 12 weeks | "Response to therapy" Death |

USA | Mild to moderate | Serious |

Clinical success: 50/59 participants 85% (73% to 93%) Death: 1/59 |

2/59 participants withdrew due to adverse events, and responded to AmB. |

| ACTG174, 1994 | Single arm trial | 49 with PDH |

Initial protocol FCN 1200 mg, then 600 mg OD for 8 weeks Revised protocol FCN 1200 mg, then 80 mg OD for 8 weeks |

"Treatment response" | USA | Mild to moderate | Serious |

Clinical success: 36/49 participants. 74% (59% to 85%) Revised protocol |

2 discontinuations due to toxicity, unclear if induction or maintenance. |

| Johnson 2002 | RCT | 81 with PDH | lAmB (55 participants) dAmB (26 participants) |

Efficacy: "Clinical success" Safety: early discontinuation |

USA | Moderate to severe | Low |

Clinical success: lAmB: 82% (69% to 91%) 45/55 participants. dAmB: 56% (37% to 76%) 14/25 participants. RR 1.46 (1.01 to 2.11) Death: lAmB: 1/53 (2%) dAmB: 3/24 (13%) RR 0.15 (0.02 to 1.38) |

Early discontinuation: 1/53 (2%) with lAmB vs 2/24 (8%) with dAmB RR 0.23 (95% CI 0.02 to 2.38) Nephrotoxicity: 5/53 (9%) with lAmB vs 9/24 (37%) with dAmB RR 0.25 (95% CI 0.09 to 0.67) Of note, authors did not report specific data in relation to other commonly recognized adverse effects, including anaemia. |

| Luckett 2015 | Retrospective cohort study | 56 with HIV and PDH | ITRA/VORI/POSA AmB |

Death (90‐day histoplasmosis‐related) Triazole failure |

USA | Mild to severe | Serious |

Death 5/56 participants. Not reported by treatment regimen. Clinical success: triazole induction successful in 20/24 participants 83% (62% to 95%) |

No safety issues reported. |

| AmB: amphotericin B; BD: twice daily; CI: confidence interval; dAmB: deoxycholate amphotericin B; FCN: fluconazole; ITRA: itraconazole; IAmB: liposomal amphotericin B; n: number of participants; OD: once daily; PDH: progressive disseminated histoplasmosis; POSA: posaconazole; RCT: randomized controlled trial; RR: risk ratio; VORI: voriconazole. | |||||||||

2. Maintenance therapy

Less than 12 months of oral itraconazole compared to 12 months or greater of oral itraconazole

No included study compared less than 12 months of oral itraconazole and 12 months or greater of oral itraconazole.

Continuation of antifungals versus discontinuation of antifungals

This result is summarized in Table 6.

5. Additional summary 1: amphotericin B formulations versus azoles.

| Early ART compared with deferred ART for PDH in HIV | |||

|

Patient or population: adults with HIV and progressive disseminated histoplasmosis Settings: endemic areas Intervention: induction therapy with triazoles Comparison: induction therapy with amphotericin B formulations | |||

| Outcomes | Narrative summary | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Treatment success | No RCTs make direct comparisons of amphotericin B and triazoles. Treatment success of triazoles (other than fluconazole) were 83% and 85% in the 2 studies which reported them. | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b |

— |

| ART: antiretroviral therapy; PDH: progressive disseminated histoplasmosis; RCT: randomized controlled trial. | |||

aDowngraded two levels for serious imprecision. The CIs are wide due to small numbers of participants. bDowngraded one level for serious indirectness. No studies report direct comparisons.

One prospective single‐arm cohort study followed a cohort of participants who discontinued antifungal therapy after at least 12 months, providing the participant had received at least six months of ART and had achieved a CD4 count of 150 cells/μL or greater (Goldman 2004). There were no relapses in 32 participants who discontinued therapy after 12 months.

Treatment success rates for modalities of maintenance therapies

'Narrative results table 2' indicates crude treatment success rates for different maintenance therapies used in studies.

Itraconazole

Two single arm trials reported low relapse rates of approximately 0.5% with itraconazole (ACTG084, 1992; ACTG120, 1992).

Fluconazole

One single arm trial was discontinued early due to higher relapse rates (11/36 participants; 30%, 95% CI 16% to 48%) (ACTG174, 1994). This trial used 400 mg doses of fluconazole after induction with fluconazole.

Narrative results table 2: maintenance therapy

| Study | Method | Participants | Interventions | Primary outcomes | Setting | Disease severity | Overall risk of bias | Narrative of efficacy findings | Narrative of safety findings |

| Studies assessing discontinuation of oral antifungals | |||||||||

| Goldman 2004 | Prospective cohort study (single arm) | 32 | Discontinuation after > 12 months of ITRA/FCN/AmB | Relapse after 1 year | USA | ≥ 6 months of ART. CD4 count < 150 cells/μL |

Serious | No relapses after 12 months of discontinuation of antifungal therapy. | No safety issues reported. |

| Studies reporting outcomes of maintenance therapy regimens | |||||||||

| ACTG084, 1992 | Single arm trial | 42 (after dAmB induction) | ITRA 200 mg BD; continuous | Relapse Death |

USA | No ART Median CD4 count 47 cells/μL (35 participants) |

Serious |

Relapse: 2/42 participants (0.5%, 95% CI 0.05% to 16%) Median follow‐up 98 weeks Death: 1/42 deaths attributed to PDH |

Treatment discontinuation in 1/42 participants Severe or life‐threatening adverse events in 37/42 participants, attributed mainly to HIV infection, opportunistic infections, and adverse effects of other medications. |

| ACTG120, 1992 | Single arm trial | 46 (of 59 enrolled) | ITRA 200 mg (26 participants) ITRA 400 mg (18 participants) ITRA 600 mg (2 participants) 4 participants remained on doses > 200 mg. Median duration 64 weeks (range 7–120 weeks) |

Relapse | USA | No ART Median CD4 29 cells/µL |

Serious |

Relapse: 2/46 participants (0.4%, 95% CI 0.05% to 14%) Median follow‐up 87 weeks Death: 1/46 deaths due to relapse |

Treatment discontinuation in 8/46 participants. 24/46 participants enrolled known to have died, including discontinuations; pre‐ART. |

| ACTG174, 1994 | Single arm trial | 49 with PDH, 36 entered maintenance therapy | FCN 400 mg Continuous Median duration 30 weeks (early termination of study) |

Relapse | USA | No ART Mild to severe |

Serious |

Relapse: 11/36 participants (30%, 95% CI 16% to 48%) |

2 discontinuations due to toxicity, unclear if induction or maintenance. |

| AmB: amphotericin B; ART: antiretroviral therapy; BD: twice daily; dAmB: deoxycholate amphotericin B; FCN: fluconazole; ITRA: itraconazole; n: number of participants; PDH: progressive disseminated histoplasmosis. | |||||||||

3. ART initiation

One trial compared early ART initiation to late ART initiation in people with coexisting opportunistic infections (ACTG‐A5164, 2009). There were 10/282 participants with a presumptive or confirmed diagnosis of histoplasmosis. No diagnostic criteria were given for histoplasmosis. One participant with histoplasmosis in each trial arm developed IRIS. Both survived. One out of seven participants in the early ART died by day 30. None of the three participants with histoplasmosis in the delayed group died by day 30. This result is summarized in 'Narrative results table 3' and Table 7.

6. Additional summary 2: early versus deferred ART.

| Early ART compared with deferred ART for PDH in HIV | ||||||

|

Patient or population: adults with HIV and progressive disseminated histoplasmosis Settings: endemic areas Intervention: early ART (< 14 days) Comparison: late ART (> 14 days) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative risks | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| IRIS | 1/3 participantsa | 1/7 participantsa |

RR 0.43 (0.04 to 4.82) |

10 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb,c |

We do not know if early ART increases the risk of IRIS in people with HIV and PDH. |

| ART: antiretroviral therapy; IRIS: immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome; PDH: progressive disseminated histoplasmosis; RCT: randomized controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

a1/3 people with histoplasmosis in deferred ART arm developed histoplasma IRIS (day 47). 1/7 people with histoplasmosis in early ART arm developed hepatitis C IRIS (day 14). bDowngraded two levels for serious imprecision. The CI was wide. cDowngraded one level for serious indirectness. The trial only included 10 participants with histoplasmosis and the case definitions were not stated.

One additional study reported crude incidence rates of histoplasma IRIS including paradoxical IRIS (flare‐up of a previously treated histoplasmosis) (Melzani 2020). This indicated an overall incidence rate of 0.74 cases per 1000 person‐years. This study does not directly answer the objective of early versus deferred ART, but provides an indication of baseline risk.

Narrative results table 3: antiretroviral initiation

| Study | Method | Participants | Interventions | Outcomes | Setting | Disease severity | Overall risk of bias | Narrative of findings |

| ACTG‐A5164, 2009 | RCT | 282, AIDS‐related opportunist infections 10 people with histoplasmosis |

Early ART (n 7) Deferred ART (n 3) |

Primary: composite endpoint of death and HIV viral load. Safety: IRIS; lab adverse events Grades 2–4; clinical adverse events Grades 2‐4. |

USA, South Africa | Baseline median CD4 count 29 (IQR 10–55) cells/μL | Low | 1/7 participants with histoplasmosis dies in the early ART group. 0/3 participants with histoplasmosis died in the deferred ART group. 1/3 people with histoplasmosis in deferred ART arm developed histoplasma IRIS (day 47). IRIS aetiology: hepatitis C. Survived. 1/7 people with histoplasmosis in early ART arm developed hepatitis C IRIS (day 14). IRIS aetiology: histoplasmosis. Survived. |

| ART: antiretroviral therapy; IQR: interquartile range; IRIS: immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. | ||||||||

Discussion

Summary of main results

For 'Objective 1. Induction' comparing liposomal amphotericin B to other antifungals, four studies met the inclusion criteria: one RCT with 81 participants and three non‐randomized studies with 164 participants. We judged all three non‐randomized studies at serious risk of bias. Compared to deoxycholate amphotericin B, liposomal amphotericin B may have higher clinical success rates (low‐certainty evidence), and has lower rates of nephrotoxicity (high‐certainty evidence). We do not know if all amphotericin B formulations are more effective than azoles for the induction phase of management (very low‐certainty evidence).

For 'Objective 2. Maintenance', comparing less than 12 months of oral antifungal treatment to greater than 12 months, no studies met the inclusion criteria.

For both objectives 1 and 2, fluconazole performed poorly in comparison to other azoles in the single‐arm trial which studied this (ACTG174, 1994). No further trials were done as there was no longer sufficient equipoise to justify this.

'Objective 3: ART' sought to compare early and delayed initiation of ART. One RCT with 282 participants met the inclusion criteria. Only 10 participants had coexisting HIV and a presumptive or confirmed diagnosis of PDH. By day 30, one of seven participants in the 'early' arm and none of the three participants in the 'late' arm died. We do not know the efficacy and safety outcomes of early versus late initiation of ART (very low‐certainty evidence).

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The overall evidence was limited; therefore, we were unable to address all the objectives of our review. Most studies were in the USA and such findings may not be generalizable to low‐resource settings as availability of liposomal amphotericin B and management of HIV may differ. This affects the external validity of our review. There is insufficient evidence to be confident that azoles and other formulations of amphotericin are as effective and safe as liposomal amphotericin B in the induction phase of the management of PDH in people living with HIV. Clinical practice may be governed by availability. Current clinical practice would indicate that shorter courses of maintenance therapy may be acceptable; however, there is insufficient evidence available to corroborate or refute this practice. There is insufficient evidence to be confident of the safety of discontinuation of maintenance therapy before 12 months or the timing of ART. Overall, clinical practice tends to favour early ART in most situations. The low rates of IRIS in the single RCT do not present a signal that this practice is unsafe; however, there is insufficient evidence to confirm this. It seems that people in resource‐limited settings are doing what they are able to do.

Certainty of the evidence

Overall, the certainty of the evidence for most outcomes was low or very low. Non‐randomized study designs predominate in this area of research, many of which were critically compromised by uncontrolled confounding. For the comparison of liposomal amphotericin B to deoxycholate amphotericin B for induction therapy, there was high‐certainty evidence of lower rates of nephrotoxicity (RR 0.25, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.67; 1 study, 77 participants). Evidence for clinical success for this comparison was of low certainty due to very serious imprecision indicating that further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect (RR 1.46, 95% CI 1.01 to 2.11; 1 study, 80 participants). For maintenance regimens, all six studies were of a non‐randomized design, at serious risk of bias, and they could only provide low‐certainty evidence.

Potential biases in the review process

To minimize the effect of all domains of bias in the non‐randomized studies we presented only those at serious risk of bias. There is little evidence available from populations outside the USA.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Liposomal amphotericin B has previously been found to be significantly safer than conventional amphotericin B with respect to renal toxicity in PDH. One systematic review published in 2015 studying any invasive fungal infections reported an effect size of RR 0.49 (95% CI 0.40 to 0.59; 12 studies, 2298 participants; Botero Aguirre 2015).

There is insufficient evidence to confidently challenge or concur with current clinical guidelines on duration of maintenance therapy (Wheat 2007).

One systematic review that investigated the effects of early versus late ART in participants with coexisting HIV and cryptococcal meningitis found the RR for development of IRIS to be 3.56 (95% CI 0.51 to 25.02, 2 RCTs). The authors graded this evidence as very‐low certainty due to imprecision, risk of bias, and indirectness indicating that they had little confidence in the effect estimate. This is consistent with the certainty of our findings for this outcome although the effect size of our included study was considerably smaller (RR 0.43, 95% CI 0.04 to 4.82; 1 study, 10 participants). This study also concluded that the risk of death appeared to be higher with early ART, leading to World Health Organization recommendations that treatment should be deferred for four to six weeks (Eshun‐Wilson 2018).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Liposomal amphotericin B appears to be a better choice compared to deoxycholate amphotericin B for treating progressive disseminated histoplasmosis in people with HIV. Fluconazole appears unsuitable for induction or maintenance.

Implications for research.

As there is very low‐certainty evidence to inform other treatment choices, we recommend further prospective research. A priority question is whether in people with a clinical and immunological response to therapy, maintenance antifungal therapy can be safely discontinued earlier than 12 months. A further question is when is the optimal time to start ART, and in what circumstances the risk of IRIS may be higher? The high and varying costs of appropriate oral antifungal agents make these questions more pertinent.

History

Review first published: Issue 4, 2020

Acknowledgements

The Academic Editor is Professor George Rutherford.

We acknowledge the contribution made by the clinical experts in the development of the research questions studied in this review. We thank Vittoria Lutje, Information Specialist at the Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group (CIDG) for conducting the searches. We thank all the library staff at Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (LSTM), especially Cathy Booth, for their assistance in obtaining articles. We thank Paul Garner for his guidance throughout the review.

We thank the members of the Pan American Health Organization Guideline Development Group who helped develop the questions for the review.

MM, PH, and the CIDG editorial base are supported by the Research, Evidence and Development Initiative (READ‐It). READ‐It (project number 300342‐104) is funded by UK aid from the UK government; however, the views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK government’s official policies.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Detailed search strategies

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials Issue 3 of 12, March 2020

#1 MeSH descriptor: [HIV] explode all trees

#2 MeSH descriptor: [HIV Infections] explode all trees

#3 Hiv OR hiv‐1 OR hiv‐2* OR hiv1 OR hiv2 OR hiv infect* OR human immunodeficiency virus OR human immunedeficiency virus OR human immuno‐deficiency virus OR human immune‐deficiency virus OR ((human immun*) AND (deficiency virus )) OR acquired immunodeficiency syndrome OR acquired immunedeficiency syndrome OR acquired immuno‐deficiency syndrome OR acquired immune‐deficiency syndrome OR ((acquired immun*) AND (deficiency syndrome))

#4 #1 or #2 or #3

#5 MeSH descriptor: [Histoplasma] explode all trees

#6 MeSH descriptor: [Histoplasmosis] explode all trees

#7 histoplasm*

#8 #5 or #6 or #7

#9 #4 and #8

PubMed (MEDLINE)

| Search set | Search terms |

| 1 | ((HIV Infections[MeSH] OR HIV[MeSH] OR (Hiv OR hiv‐1 OR hiv‐2* OR hiv1 OR hiv2 OR hiv infect* OR human immunodeficiency virus OR human immunedeficiency virus OR human immuno‐deficiency virus OR human immune‐deficiency virus OR ((human immun*) AND (deficiency virus )) OR acquired immunodeficiency syndrome OR acquired immunedeficiency syndrome OR acquired immuno‐deficiency syndrome OR acquired immune‐deficiency syndrome OR ((acquired immun*) AND (deficiency syndrome)) Field: Title/Abstract |

| 2 | "Histoplasma"[Mesh] OR "Histoplasmosis"[Mesh] or Histoplasm* Field: Title/Abstract |

| 3 | 1 and 2 |

| 4 | "Antifungal Agents"[Mesh] |

| 5 | "Amphotericin B"[Mesh]) OR amphotericin Field: Title/Abstract |

| 6 | "Itraconazole"[Mesh]) OR itraconazole Field: Title/Abstract |

| 7 | 4 or 5or 6 |

| 8 | 3 and 7 |

| 9 | "Randomized Controlled Trial" [Publication Type] OR "Controlled Clinical Trial" [Publication Type] |

| 10 | randomized or placebo or randomly or trial or groups Field: Title/Abstract |

| 11 | drug therapy [Subheading] |

| 12 | "Interrupted Time Series Analysis"[Mesh] |

| 13 | "Controlled Before‐After Studies"[Mesh |

| 14 | “time series” Field: Title/Abstract |

| 15 | "cross‐over studies"[MeSH] or crossover or cross‐over Field: Title/Abstract |

| 16 | "longitudinal studies"[MeSH] |

| 17 | Longitudinal or cohort* Field: Title/Abstract |

| 18 | "Systematic Review" [Publication Type] |

| 19 | metaanalysis or meta‐analysis or “systematic review” Field: Title/Abstract |

| 20 | 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 |

| 21 | 8 and 20 |

Embase 1947‐Present, updated daily

Search Strategy:

‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐

1 HIV infection.mp. or HIV Infections/

2 exp HIV/ or Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome/

3 (Hiv or hiv‐1 or hiv‐2* or hiv1 or hiv2 or hiv infect* or human immunodeficiency virus or human immunedeficiency virus or human immuno‐deficiency virus or human immune‐deficiency virus or (human immun* and deficiency virus) or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome or acquired immunedeficiency syndrome or acquired immuno‐deficiency syndrome or acquired immune‐deficiency syndrome or (acquired immun* and deficiency syndrome)).mp.

4 aids.mp. or acquired immune deficiency syndrome/

5 1 or 2 or 3 or 4

6 histoplasma.mp. or Histoplasma/

7 histoplasmosis.mp. or histoplasmosis/

8 6 or 7

9 5 and 8

10 antifungal agents.mp. or antifungal agent/

11 itraconazole.mp. or itraconazole/

12 amphotericin B/ or Amphotericin B.mp.

13 10 or 11 or 12

14 9 and 13

15 randomized controlled trial/ or controlled clinical trial/

16 (randomized or placebo or randomly or trial or groups).mp

17 "time series".mp. or time series analysis/

18 (controlled before and after).mp.

19 crossover procedure/

20 cohort analysis/ or prospective study/ or cohort.mp.

21 longitudinal study.mp. or longitudinal study/

22 systematic review.mp. or "systematic review"/

23 (metaanalysis or meta‐analysis).mp.

24 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23

25 14 and 24

26 9 and 24

27 25 or 26

Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI‐EXPANDED) Conference Proceedings Citation Index‐Science (CPCI‐S) and BIOSIS Previews (all from Web of Science)

| # | 9 | #8 AND #5 |

| # | 8 | #7 OR #6 |

| # | 7 | TOPIC: (antifungal*) |

| # | 6 | TOPIC: (itraconazole or amphotericin) |

| # | 5 | #4 AND #3 |

| # | 4 | TOPIC: (histoplasma or histoplasmosis) |

| # | 3 | #2 OR #1 |

| # | 2 | TOPIC: (Hiv OR hiv‐1 OR hiv‐2* OR hiv1 OR hiv2 OR hiv infect* OR human immunodeficiency virus OR human immunedeficiency virus OR human immuno‐deficiency virus OR human immune‐deficiency virus OR ((human immun*) AND (deficiency virus )) OR acquired immunodeficiency syndrome OR acquired immunedeficiency syndrome OR acquired immuno‐deficiency syndrome OR acquired immune‐deficiency syndrome OR ((acquired immun*) AND (deficiency syndrome))) |

| # 1 | TOPIC: (HIV OR AIDS OR "human immunodeficiency virus" or "acquired immunodeficiency syndrome" or AIDS) |

WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP), Clinicaltrials.gov, and ISRCTN registry

histoplasm* and HIV*

Appendix 2. ROBINS‐I methodology

Risk of bias: ROBINS‐I

Target trial(s)

To determine bias, as defined by systematic differences between a non‐randomized study and a hypothetical pragmatic randomized trial, we formulated the following target trial (Sterne 2016).

Design: individually randomized

Participants: HIV‐positive children, adolescents, and adults with a clinical diagnosis of progressive disseminated histoplasmosis.

| Objective | Intervention | Comparisons |

| 1. Induction | Liposomal amphotericin B (3.0 mg/kg daily) for 1–2 weeks | Lipid complex amphotericin B Deoxycholate amphotericin B Other antifungal agents |

| 2. Maintenance | Oral antifungal treatment for < 12 months | Oral antifungal treatment for ≥ 12 months |

| 3. ART | Early initiation (within 4 weeks of commencing antifungal therapy) | Delayed initiation (> 4 weeks after starting antifungal treatment |

The aim was to assess the effect of assignment to the intervention, that is, we assessed studies on the basis of intention to treat. Judgements were guided by the use of signalling questions at domain level using ROBINS‐I methodology (Sterne 2016).

Confounding domains relevant to all or most studies that were determined a priori informed by current literature and clinical expertise.

Table A a priori confounding domains

| Confounding domains relevant to all or most studies | Cointerventions that could be different between intervention groups and that could impact on outcomes |

| Severity of PDH | ART at time of PDH diagnosis |

| Severity of HIV (CD4 count) | Supportive therapy |

| Comorbidities and comedications | — |

| ART: antiretroviral therapy; PDH: progressive disseminated histoplasmosis | |

Severity of progressive disseminated histoplasmosis (PDH) and HIV were considered likely to influence clinicians to favour intravenous therapy including liposomal amphotericin B. Comorbidities and comedications were also determined to influence medical management. In particular, use of medications which may interact with azoles may cause a clinician to favour use of amphotericin during induction therapy.

Overall risk of bias judgements were determined using the following table from detailed guidance on the use of ROBINS‐I. Sterne JAC, Higgins JPT, Elbers RG, Reeves BC and the development group for ROBINS‐I. Risk Of Bias In Non‐randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS‐I): detailed guidance, updated 12 October 2016. Available from www.riskofbias.info (accessed 4 June 2019).

Table B guidance on ROBINS‐I judgements

| Response option | Criteria |

| Low risk of bias (the study is comparable to a well‐performed randomized trial). | The study is at low risk of bias for all domains. |

| Moderate risk of bias (the study appears to provide sound evidence for a non‐randomized study but cannot be considered comparable to a well‐performed randomized trial). | The study is at low or moderate risk of bias for all domains. |

| Serious risk of bias (the study has some important problems). | The study is at serious risk of bias in ≥ 1 domain, but not at critical risk of bias in any domain. |

| Critical risk of bias (the study is too problematic to provide any useful evidence and should not be included in any synthesis). | The study is at critical risk of bias in ≥ 1 domain. |

| No information on which to base a judgement about risk of bias. | There is no clear indication that the study is at serious or critical risk of bias and there is a lack of information in ≥ 1 key domains of bias. |

| Sterne 2016. | |

Table C ROBINS‐I. Assessments of non‐randomized studies

| Study:Luckett 2015. Outcome: treatment success | ||||

| Confounding domains | Measured variable(s) | Is there evidence that controlling for this variable was unnecessary? | Is the confounding domain measured validly and reliably? | OPTIONAL Is failure to adjust for this variable expected to favour intervention or comparator |

| Severity of PDH | Severe, moderate, and mild illness were defined | No | Yes | — |

| Severity of HIV | CD4 count and viral load reported | No | Yes | — |

| Comorbidities and comedications | Not reported | No | Not measured | Comorbidities likely to influence clinicians to favour liposomal amphotericin. |

| Cointerventions | Is there evidence that controlling for this cointervention was unnecessary? | Is presence of this cointervention likely to favour outcomes in the intervention or comparator? | ||

| ART at time of PDH diagnosis | No, remains important cointervention. 27% on ART prior to study. 1/3 adherent. | Favour intervention | ||

| Supportive therapy | Reported level of clinical care (e.g. ICU care) | Favour intervention | ||

| Bias domain | Signalling questions | Comments | Risk of bias judgement | |

| Bias due to confounding | 1.1–1.8 | Authors described severity of PDH, and reported median and range of CD4 count. Authors did not report any comorbidities or comedications. Baseline characteristics of participants in azole and amphotericin groups not reported. Authors did not report use of appropriate statistical methods to control for important baseline confounding. Rationale for treatment choice in azole and amphotericin groups not reported. There was insufficient information to judge bias due to confounding. | No information | |

| Bias in participant selection | 2.1–2.5 | No evidence that selection into the study based on participant characteristics observed after intervention. Authors did not report the time between start of follow‐up and start of intervention. | Moderate | |

| Bias in classification of intervention | 3.1–3.3 | No information about dose, frequency, and timing of interventions. Information was collected retrospectively. | Serious | |

| Bias due to deviations from intended intervention | 4.1–4.6 | No evidence of deviations from interventions. No comment on whether patients not on ART were commenced on ART. No measure of adherence to antifungal therapy. | No information | |

| Bias due to missing data | 5.1–5.5 | No information regarding loss to follow‐up. | No information | |

| Bias in measurement of outcomes | 6.1–6.4 | For mortality outcome, unlikely to display measurement bias. For treatment failure outcome, based on clinician judgement only, likely to favour switch from azole to amphotericin. | Serious | |

| Bias in selection of reported result | 7.1–7.3 | Limited analysis. | No information | |

| Overall bias | SERIOUS | |||

| Study:Mootsikapun 2006.Outcome 1: inhospital mortality | ||||

| Confounding domains | Measured variable(s) | Is there evidence that controlling for this variable was unnecessary? | Is the confounding domain measured validly and reliably? | OPTIONAL Is failure to adjust for this variable expected to favour intervention or comparator |

| Severity of PDH | Not reported | No | No information provided | — |

| Severity of HIV | Not reported | No | No information provided | — |

| Comorbidities and comedications | None reported | No | No information provided | — |

| Cointerventions | Is there evidence that controlling for this cointervention was unnecessary? | Is presence of this cointervention likely to favour outcomes in the intervention or comparator? | ||

| ART at time of PDH diagnosis | No | — | ||

| Supportive therapy | No | — | ||

| Bias domain | Signalling questions | Comments | Risk of bias judgement | |

| Bias due to confounding | 1.1–1.8 | ≥ 1 known important domain was not appropriately measured or controlled for. Details of disease severity, comedications, and comorbidities not provided for the 3 inhospital deaths. | Serious | |

| Bias in participant selection | 2.1–2.5 | Authors reported data on 29 participants who received AmB 0.7 mg/kg/day. Data not provided on alternate treatment regimens or time to treatment; however, since all participants received the same treatment, it is probable that selection into the study was not related to the outcome. | Moderate | |

| Bias in classification of intervention | 3.1–3.3 | Comparison was between disease populations not intervention groups. Intervention status was well defined. | Moderate | |

| Bias due to deviations from intended intervention | 4.1–4.6 | Deviations were not reported. Important cointerventions were not reported. | No information | |

| Bias due to missing data | 5.1–5.5 | Data reported on inhospital deaths likely to be reasonably complete. | Low | |

| Bias in measurement of outcomes | 6.1–6.4 | The outcome measure was unlikely to be influenced by knowledge of the intervention. | Low | |

| Bias in selection of reported result | 7.1–7.3 | There is too little information to make a judgement on bias in reporting in this retrospective review of medical records. | No information | |

| Overall bias | SERIOUS | |||

| Study:Mootsikapun 2006. Outcome 2: relapse on maintenance itraconazole. Median follow‐up 22 months (1–75 months) | ||||

| Confounding domains | Measured variable(s) | Is there evidence that controlling for this variable was unnecessary? | Is the confounding domain measured validly and reliably? | OPTIONAL Is failure to adjust for this variable expected to favour intervention or comparator |

| Severity of PDH | Not reported | No | — | — |

| Severity of HIV | Not reported | No | — | — |

| Comorbidities and comedications | None reported | No | — | — |

| Cointerventions | Is there evidence that controlling for this cointervention was unnecessary? | Is presence of this cointervention likely to favour outcomes in the intervention or comparator? | ||

| ART at time of PDH diagnosis | No | — | ||

| Supportive therapy | No | — | ||

| Bias domain | Signalling questions | Comments | Risk of bias judgement | |

| Bias due to confounding | 1.1–1.8 | ≥ 1 known important domain was not appropriately measured or controlled for: details of disease severity, comedications, and comorbidities not provided for 27 participants discharged from hospital. | Serious | |

| Bias in participant selection | 2.1–2.5 | Maintenance therapy was commenced in those who responded to initial treatment on AmB. Timing of start of maintenance therapy was not reported. Selection into this part of the study was related to the intervention. | Serious | |

| Bias in classification of intervention | 3.1–3.3 | Authors reported that participants who responded to treatment with AmB received oral itraconazole 400 mg/day for 3 months then 200 mg/day afterwards. Median follow‐up for participants was 22 (range 1–75) months. Although response to treatment was likely to have been a clinical decision bias intervention, status appeared to be adequately defined. Range of duration of follow‐up was wide. | Moderate | |

| Bias due to deviations from intended intervention | 4.1–4.6 | Cointerventions were not reported. Deviations from practice not reported. | Moderate | |

| Bias due to missing data | 5.1–5.5 | Data obtained from medical records from a 7‐year period. Range of follow‐up was 1–75 months. Outcome data not provided on individual participants. There was insufficient information to base a judgement about risk of bias for this domain. | No information | |

| Bias in measurement of outcomes | 6.1–6.4 | Retrospective data collection. Unlikely to be assessor bias in participant eligibility for maintenance therapy. | Low | |

| Bias in selection of reported result | 7.1–7.3 | Authors reported no relapse in participants who had itraconazole as long‐term therapy; however, range of duration of follow‐up was wide. | Moderate | |

| Overall bias | SERIOUS | |||

| Study:Myint 2014.Outcome: relapse of histoplasmosis | ||||

| Confounding domains | Measured variable(s) | Is there evidence that controlling for this variable was unnecessary? | Is the confounding domain measured validly and reliably? | OPTIONAL Is failure to adjust for this variable expected to favour intervention or comparator |

| Severity of PDH | Defined and reported | No | — | — |

| Severity of HIV | Defined and reported | No | — | — |

| Comorbidities and comedications | ART adherence monitored with CD4 count and HIV RNA load | No | — | — |

| Cointerventions | Is there evidence that controlling for this cointervention was unnecessary? | Is presence of this cointervention likely to favour outcomes in the intervention or comparator? | ||

| ART at time of PDH diagnosis | 34% in each group (12/35, 19/56) | — | ||

| Supportive therapy | Reported | — | ||

| Bias domain | Signalling questions | Comments | Risk of bias judgement | |

| Bias due to confounding | 1.1–1.8 | Physician determined discontinuation of maintenance therapy may have been influenced by prognostic factors that were not controlled for. Multiple logistic regression used to determine variables associated with relapse; however, assignment to treatment arms was based on clinical assessment and viral load. 'Adherence to therapy' not defined. Unclear if this referred to ART, ITRA, or both. No evidence of adjustment for time‐varying confounding. | Critical | |

| Bias in participant selection | 2.1–2.5 | — | — | |

| Bias in classification of intervention | 3.1–3.3 | — | — | |

| Bias due to deviations from intended intervention | 4.1–4.6 | — | — | |

| Bias due to missing data | 5.1–5.5 | — | — | |

| Bias in measurement of outcomes | 6.1–6.4 | — | — | |

| Bias in selection of reported result | 7.1–7.3 | — | — | |

| Overall bias | CRITICAL | |||

| Study:Myint 2014.Outcome: death | ||||

| Confounding domains | Measured variable(s) | Is there evidence that controlling for this variable was unnecessary? | Is the confounding domain measured validly and reliably? | OPTIONAL Is failure to adjust for this variable expected to favour intervention or comparator |

| Severity of PDH | Defined and reported | No | Yes | — |

| Severity of HIV | Defined and reported | No | Yes | — |

| Comorbidities and comedications | ART adherence monitored with CD4 count and HIV RNA load | No | Yes | — |

| Cointerventions | Is there evidence that controlling for this cointervention was unnecessary? | Is presence of this cointervention likely to favour outcomes in the intervention or comparator? | ||

| ART at time of PDH diagnosis | No | — | ||

| Supportive therapy | No | — | ||

| Bias domain | Signalling questions | Comments | Risk of bias judgement | |

| Bias due to confounding | 1.1–1.8 | Participants in the physician continued therapy group are likely to have been more ill and therefore at higher risk of death. | Critical | |

| Bias in participant selection | 2.1–2.5 | |||

| Bias in classification of intervention | 3.1–3.3 | |||

| Bias due to deviations from intended intervention | 4.1–4.6 | |||

| Bias due to missing data | 5.1–5.5 | |||

| Bias in measurement of outcomes | 6.1–6.4 | |||

| Bias in selection of reported result | 7.1–7.3 | |||

| Overall bias | CRITICAL | |||

| Study:Negroni 2017.Outcome: response to maintenance therapy | ||||

| Confounding domains | Measured variable(s) | Is there evidence that controlling for this variable was unnecessary? | Is the confounding domain measured validly and reliably? | OPTIONAL Is failure to adjust for this variable expected to favour intervention or comparator |

| Severity of PDH | Not defined | No | ||

| Severity of HIV | CD4 count | No | ||

| Comorbidities and comedications | 17.5% on ART at baseline 41% of participants discharged from hospital continued with follow‐up of ART and maintenance therapy. Authors reported use of AmB in participants who were more ill and in those on medication likely to interact with itraconazole such as rifampicin suggesting there could have been comorbid TB. |

No | — | — |

| Cointerventions | Is there evidence that controlling for this cointervention was unnecessary? | Is presence of this cointervention likely to favour outcomes in the intervention or comparator? | ||

| ART at time of PDH diagnosis | No | — | ||

| Supportive therapy | No | — | ||

| Bias domain | Signalling questions | Comments | Risk of bias judgement | |

| Bias due to confounding | 1.1–1.8 | Comorbidity and comedications were not reported or controlled for. Outcome data were not linked to disease severity. Outcomes not reported by drug regimen. Treatment regimens varied by drug and duration. There were drug switches. | Critical | |

| Bias in participant selection | 2.1–2.5 | — | — | |

| Bias in classification of intervention | 3.1–3.3 | — | — | |

| Bias due to deviations from intended intervention | 4.1–4.6 | — | — | |

| Bias due to missing data | 5.1–5.5 | — | — | |

| Bias in measurement of outcomes | 6.1–6.4 | — | — | |

| Bias in selection of reported result | 7.1–7.3 | — | — | |

| Overall bias | CRITICAL | |||

| Study:Norris 1994.Outcome: relapse of histoplasmosis | ||||

| Confounding domains | Measured variable(s) | Is there evidence that controlling for this variable was unnecessary? | Is the confounding domain measured validly and reliably? | OPTIONAL Is failure to adjust for this variable expected to favour intervention or comparator |

| Severity of PDH | Not reported. All participants had completed induction treatment for histoplasmosis before study started. Successful induction determined clinically. Fungal cultures not performed in all patients to confirm success of induction. | — | — | — |

| Severity of HIV | No measured variable reported. | — | — | — |

| Comorbidities and comedications | Multiple drug regimens used prior to intervention. HIV management not reported. |

— | — | — |

| Cointerventions | Is there evidence that controlling for this cointervention was unnecessary? | Is presence of this cointervention likely to favour outcomes in the intervention or comparator? | ||

| ART at time of PDH diagnosis | No | — | ||

| Supportive therapy | No | — | ||

| Bias domain | Signalling questions | Comments | Risk of bias judgement | |

| Bias due to confounding | 1.1–1.8 | Authors reported no specific criteria to select participants for intervention. Criteria included unavailability of ITRA and preference for oral therapy. Intervention group determined by treating physicians who also evaluated clinical evidence of relapse and adverse effects. Severity of HIV, comorbidities, and comedication were not reported. | Critical | |

| Bias in participant selection | 2.1–2.5 | — | — | |

| Bias in classification of intervention | 3.1–3.3 | — | — | |

| Bias due to deviations from intended intervention | 4.1–4.6 | — | — | |

| Bias due to missing data | 5.1–5.5 | — | — | |

| Bias in measurement of outcomes | 6.1–6.4 | — | — | |

| Bias in selection of reported result | 7.1–7.3 | — | — | |

| Overall bias | CRITICAL | |||

| Study:Pietrobon 2004. Outcome: mortality | ||||

| Confounding domains | Measured variable(s) | Is there evidence that controlling for this variable was unnecessary? | Is the confounding domain measured validly and reliably? | OPTIONAL Is failure to adjust for this variable expected to favour intervention or comparator |

| Severity of PDH | Not defined or reported. | No | No | — |

| Severity of HIV | Authors reported 11/16 participants with histoplasmosis had CD4 count < 50 cells/μL | No | Yes | — |

| Comorbidities and comedications | Authors reported none of participants were receiving ART. Study population was 16. Comorbidities mentioned but not systemically. | No | No | — |

| Cointerventions | Is there evidence that controlling for this cointervention was unnecessary? | Is presence of this cointervention likely to favour outcomes in the intervention or comparator? | ||

| ART at time of PDH diagnosis | No | — | ||

| Supportive therapy | No | — | ||

| Bias domain | Signalling questions | Comments | Risk of bias judgement | |