Abstract

Introduction

Because many patients are first exposed to opioids after general surgery procedures, surgical stewardship or the use of opioids is critical in addressing the opioid crisis. We developed a multi-component, opioid reduction program to minimize these of opioids after surgery. Our objectives were to assess patient exposure to the intervention and to investigate the association with post-operative use and disposal of opiods.

Methods

We implemented a multi-component intervention, including patient education, the settings of expectation, the education of the providers, and an in-clinic disposal box in our large, academic, general surgery clinic. From April-December 2018, patients were surveyed by phone 30–60 days after operation regarding their experience with post-operative pain management. The association between patient education and preparedness to manage pain was assessed using chi-squared tests. Education, preparedness, and clinical factors were evaluated for association with quantity of pills used using ANOVA and multivariable linear regression.

Results

Of the 389 eligible patients, 112 responded to the survey (28.8%). Patients receiving both pre- and post-operative education were more likely to feel prepared to manage pain than those who only received the education pre- or post-operatively (91% vs 68%, p=0.01). Patients who felt prepared to manage their pain used 9.1 fewer pills on average than those who did not (p=0.01). Fourteen patients (24%) with excess pills disposed of them. Pre-operative education was associated with disposal of excess pills (30% vs 0%, p<0.05).

Conclusions

Exposure to clinic-based interventions, particularly pre-operatively, can increase patient preparedness to manage post-operative pain and decrease the quantity of opioids used. Additional strategies are needed to increase appropriate disposal of unused opiods.

TOC Statement

The authors implement a multi-component intervention to decrease the use of reduce opioids postoperatively, use and increase disposal of excess opioids after surgery, and to investigate patient-reported outcomes. This report is important because it highlights the crucial role of preoperative education and counseling and the need for further work to encourage appropriate disposal.

Introduction

Opioid overdose continues to be a major cause of mortality in the United States, with 47,600 deaths reported by the Centers for Disease Control in 2017.1 Many opioid-naïve patients are first exposed to opioids after general surgery procedures.2–5 With >70% of the opioids prescribed after an operation going unused, proper surgical opioid stewardship of opiod usage by us as surgeons is critical in preventing misuse and abuse of opiods not only in the patient but also in the community.3,6

Several initiatives have now shown that surgical providers can prescribe fewer opioids at discharge without consequences of increased patient suffering or requests for refills.7–9 These clinician-targeted strategies, such as decreasing the default prescription quantities in the electronic health record and grand rounds presentations, have resulted in decreases in the prescribing of opiods postoperatively.9,10 While decreasing the prescribing of opiods is important, decreasing the amount of opioids actually used by patients and disposing of any excess pills after an operation would have further beneficial effects on decreasing unintended chronic opioid use.11,12 While this is an important current topic in the house of surgery, there remains a paucity of evidence regarding minimization interventions targeted and tailored to patients concerning the ap[propriate use of opiods postoperatively.

To address this gap, we developed a multi-component.-opioid-reduction program dedicated to minimizing patients’ use of opiods postoperatively. This comprehensive, clinic-based intervention spanned all phases of care and specifically focused on engaging patients in their pain management both preoperatively as well as postoperatively. Given the complexity of the intervention, we evaluated both implementation effectiveness as well as intervention effectiveness. Specifically, our objectives were twofold: (1) to assess patient exposure to the intervention, and (2) to investigate associations of exposure to the intervention with post-operative opioid use and disposal rates of unused opiods.

Methods

Intervention

We developed a multi-component intervention to encourage proper post-operative opioid stewardship within a general surgery clinic at a large academic medical center. The clinic includes nine surgeons across several specialties (general, bariatric/MIS, colorectal) performing various operations, including hernia repairs, cholecystectomy, colectomy, and benign foregut operations. The intervention consisted of (1) provider education, (2) standardized materials of patient education, (3) pre-operative settings of realistic patient expectations regarding post-operative pain and pain management, and (4) installation of an in-clinic, opioid retrieval/disposal box.

Provider education included recognition of the clinicians’ role in the current opioid crisis, the rates of overprescribing within general surgery, the importance of multimodal strategies to minimize the postoperative use of opiods by patients while adequately managing pain, and how to effectively set realistic expectations of postoperative pain management with patients. This program was delivered by the surgeon champion of this initiative (ELSEVIER HAVE THE INITIALS OF THIS CHAMPION PUT HERE BY THE AUTHORS) at the clinic faculty meetings, with all faculty members and advanced practice providers present. These messages were also part of the modules of opioid education developed and disseminated through our hospital’s Learning Management System (LMS). Prescribing recommendations based on procedure type were also disseminated and defaults built into order sets within the Electronic Medical Record (EMR).13 All residents and advanced practice providers (APPs) also received a formal training program regarding the need for stewardship in the prescribing of opioids.14 The nurse manager and clinical educator in the clinic held training sessions for the nurses, medical assistants, and other staff involved in the patient education and the process of retrieval/disposal of unused opiods p. In addition, the nursing leadership provided targeted education to individual staff members who did not provide consistent education or document appropriately.

Patient education included both pre- and post-operative components. During the initial preoperative clinic consultation, surgeons set expectations for patients about managing postoperative pain, and discussed how pain management should focus on returning to optimal function while managing pain adequately. Patients scheduling surgery then met with a nurse who walked through brochure on ‘prescription of opiods’ with them (Appendix A). The nurse highlighted the opportunity to dispose of any excess opioids in the disposal box in the clinic, and conducted further expectation setting about postoperative pain management.

Post-operatively but prior to discharge, surgeons, residents, and advanced practice providers were instructed to reinforce messages to patients and families about how to manage pain adequately by minimizing opioid use, using non-opioid therapies when possible, and how to dispose of excess pain medication safely.

Finally, an in-clinic disposal box was installed, and clinic leadership and staff were trained and educated on the importance of the disposal program. This process was done in consultation with partners at the Drug Enforcement Agency, as well as an interdisciplinary team of partners and stakeholders, including legal, risk, security, and pharmacy champions. This process introduced several complex issues; indeed, the entire process taking approximately one year. Based on this experience, a protocol was developed to guide other providers in the installation of similar disposal processes (Appendix B). Reminders about the disposal box were added to the automated call patients receive before their postoperative visits.

A multidisciplinary, implementation team made up of a surgeon, pharmacist, nurse, and administrative management developed and implemented the intervention based on a review of current practices and available literature. The program began in 2017 and has been iteratively developed and improved using quality improvement principles since that time.

Data Collection

Patients who had an elective operation between April and December 2018 were contacted by phone within 30–60 days of the planned operation and asked to participate in a survey regarding their experience with post-operative pain. If patients did not answer the first phone call, a total of 3 attempts were made to call the patient on different days before considering them non-responders. The survey assessed patient-reported pain control using the validated, Brief Pain Inventory-Pain Interference Scale15–18, patient exposure to education regarding to pain management, and patient-reported preparedness to manage post-operative pain, as well as questions regarding use of the opioids prescribed and their disposal. We obtained procedure-specific, Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes, duration of hospital stay, and the surgeon performing the procedure from the patient’s medical record. All study procedures were approved by the institutional review board of Northwestern University (ID STU00205053).

Variables and Outcomes

The first objective of this study was to assess patient exposure to the intervention. Specifically, we defined exposure as patient recall of having had an educational discussion regarding pain management with their provider. While patients were asked about both pre-operative and post-operative education, the primary exposure of interest was the pre-operative, in-clinic education and setting of expectation. The primary outcome for this objective was patient-reported preparedness to manage post-operative pain.

The second objective was to assess the effectiveness of the intervention in decreasing opioid use post-operatively. Patient education and preparedness were evaluated as exposures with the quantity of pills used post-operatively as the primary outcome for this objective. Disposal of excess, unused opioid pills was the secondary outcome.

Variables that served as covariates in the analysis were operative approach (open or minimally invasive), procedure type, and duration of stay. The duration of stay was chosen as a useful surrogate of both operative morbidity as well as any possible complication that may have occurred during the operation or in the immediate post-operative period.

Statistical Analysis

Chi-squared analysis was used to compare the rate of patient-reported preparedness to manage post-operative pain between patients who reported receiving education and those who did not. Preparedness to manage pain was dichotomized a priori from a 5-point Likert scale to “prepared” (very prepared or somewhat prepared) vs. “unprepared” (neutral, somewhat unprepared, or very unprepared).

The average quantity of pills used was compared by procedure, operative approach, patient-reported receipt of education in pain management, preparedness to manage pain, and duration of stay using antindependent-sample t-test or ANOVA where appropriate. Duration of stay was dichotomized as greater than two days or less than or equal to two days. All other covariates were categorical. Those factors found to be statistically significant on univariate analysis were assessed as predictors in a multivariable linear regression model with quantity of pills used as the outcome. Finally, we conducted post-hoc secondary analyses stratifying by procedure, as well as investigating interaction between procedure and preparedness. Statistical significance was set at an alpha of 0.05 for all analysis. All analysis was performed in STATA/SE 13.1.

Results

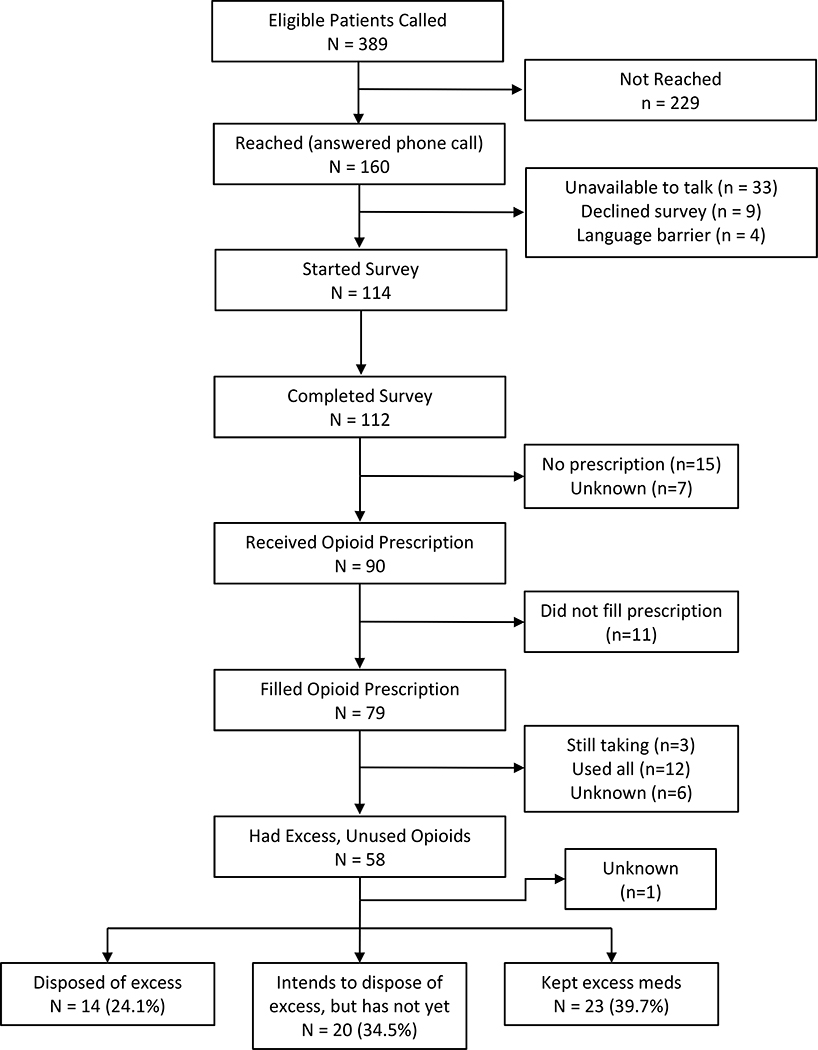

Of the 389 eligible patients contacted, 112 completed the survey (28.8% response rate). Five were excluded due to unknown procedure type. Of these 112 patients, 91 (84%) received opioid prescriptions, with 79 (88%) of whom reporting that they filled their prescriptions (Figure 1). Patients underwent various, common, general surgery procedures, including colectomy, cholecystectomy, and hernia repair, with about two-thirds of these operations being minimally invasive and one-third as open procedures (Table 1). Overall median duration of stay was 0 days [interquartile range (IQR): 0 – 2].

Figure 1.

Patient Flow Diagram

Table 1.

Patient Cohort Characteristics (n=114 Ptiewwnts)

| n | % | |

| Procedure | ||

| Foregut operations | 6 | 56% |

| Partial/Total Colectomy | 25 | 2% |

| Cholecystectomy | 33 | 31% |

| Inguinal Hernia Repair | 21 | 20% |

| Ventral/Incisional Hernia Repair | 10 | 9% |

| Umbilical Hernia Repair | 12 | 11% |

| Approach | ||

| Open | 35 | 33% |

| Minimally Invasive | 72 | 67% |

| Opioid Prescriptions | 90 | 82% |

| Mean | SD | |

| Pills used | 8.4 | 11.6 |

| Duration of Stay (median [IQR]) | 1.8 | 3.1 |

Footnote: Patients who did not receive or fill an opioid prescription were coded as 0 pills used.

Education and Preparedness

The majority of patients reported receiving education regarding pain management, with 80 (71%) receiving it pre-operatively and 98 (87%) post-operatively. Seventy-three (65%) patients reported receiving both pre-operative and post-operative education. Patients who received pre-operative education were more likely to feel prepared to manage their post-operative pain than those who did not receive pre-operative education (89% vs. 69%; p=0.01).In contrast, post-operative education was not associated with preparedness to manage pain (p=0.28). The greatest rate of preparedness for pain management was seen among patients who received both pre- and post-operative education (90%, see Table 2).

Table 2.

Pre-Operative and Post-Operative Education and Association with Preparedness to Manage Pain

| Not Prepared | Prepared | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Pre-operative education | p=0.01 | ||||

| No | 10 | 31% | 22 | 69 % | |

| Yes | 9 | 11% | 70 | 89% | |

| Post-operative education | p=0.30 | ||||

| No | 4 | 27% | 11 | 73% | |

| Yes | 15 | 16% | 82 | 85% | |

| Both | p=0.01 | ||||

| No | 12 | 31% | 27 | 69% | |

| Yes | 7 | 10% | 65 | 90% | |

Footnote: Reported p-values are from Chi2 test comparing the percent of patients prepared to manage their pain between the group that received the type of education indicated versus those who did not. Groups are not mutually exclusive (i.e. patients that received both pre- and post-operative education are in the “Yes” group for pre-operative, post-operative, and both).

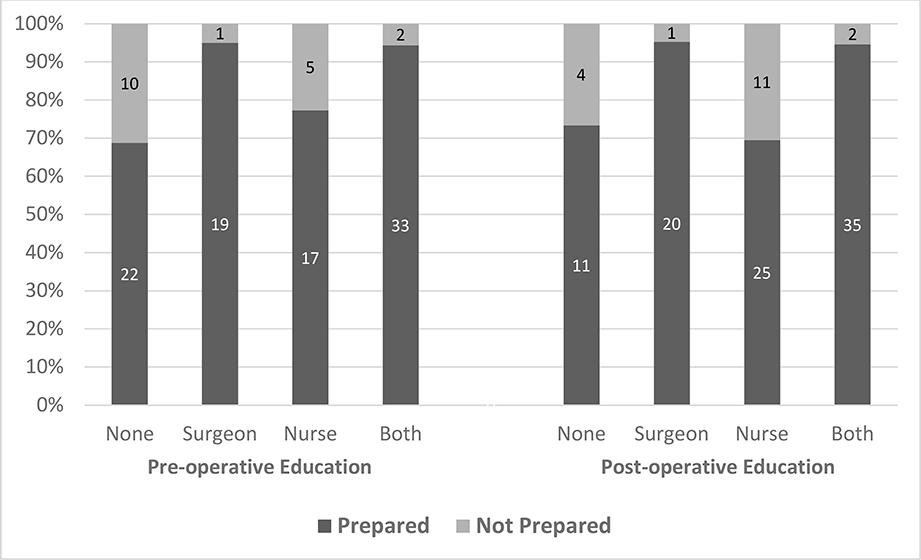

When stratifying by the patient-reported source of education, patients who reported pre-operative education from their surgeon (95% prepared) or both their surgeon and nurse (94% prepared) felt more prepared than those reporting education only from their nurse (77%, p=0.014, Figure 2). Likewise, preparedness was greater among patients reporting post-operative education from their surgeon (95%) or both their surgeon and nurse (95%) compared to those reporting their nurse as the only source (69%, p=0.009).

Figure 2. Patient Preparedness to Manage Pain, Stratified by Source of Education.

Footnote: Percentage of patients reporting preparedness to manage post-operative pain, stratified by the patient-reported source of the education. Pre-operative and post-operative education shown separately, but are not mutually exclusive.

Pills Used

Among all patients, the average quantity of pills used was 8.4 ± 11.6 with a median of 5 [IQR: 0 – 11]. The operative approach, type of procedure, and post-operative education were not s associated with the quantity of pills used post-operatively (Table 3). Pre-operative education, preparedness to manage pain, and duration of stay were all associated with fewer pills used on univariate analysis (Figure 2). Specifically, patients who received pre-operative education used on average half the quantity of pills compared to those who did not (6.6 vs 12.8; p=0.02). Similarly, the average quantity of pills used by patients who reported feeling prepared to manage their pain was less than half that of those who were not prepared (7.0 vs. 15.5; p<0.01).

Table 3.

Average Quantity of Pills Used, Associations on Univariate Analysis

| N | Mean (SD) | t-test / ANOVA | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Approach | p=0.32 | ||

| Open | 32 | 7.1 (7.8) | |

| MIS | 53 | 9.7 (13.8) | |

| Procedure | p=0.53 | ||

| Foregut operations | 4 | 17.4 (28.4) | |

| Partial/Total Colectomy | 16 | 10.8 (18.8) | |

| Cholecystectomy | 28 | 6.9 (7.1) | |

| Inguinal Hernia Repair | 20 | 9.1 (8.5) | |

| Ventral/Incisional Hernia Repair | 6 | 9.8 (10.9) | |

| Umbilical Hernia Repair | 11 | 6.0 (6.4) | |

| Pre-operative education | p=0.02 | ||

| No | 26 | 12.8 (15.3) | |

| Yes | 63 | 6.6 (9.5) | |

| Post-operative education | p=0.66 | ||

| No | 14 | 9.7 (12.9) | |

| Yes | 76 | 8.2 (11.6) | |

| Both pre- and post-operative education | p<0.05 | ||

| No | 33 | 11.6 (14.2) | |

| Yes | 56 | 6.6 (9.8) | |

| Prepared to manage pain | p<0.01 | ||

| No | 16 | 15.5 (15.6) | |

| Yes | 73 | 7.0 (10.2) | |

| Duration of Stay | p<0.01 | ||

| ≤ 2 days | 67 | 6.5 (7.0) | |

| > 2 days | 23 | 14.0 (19.0) |

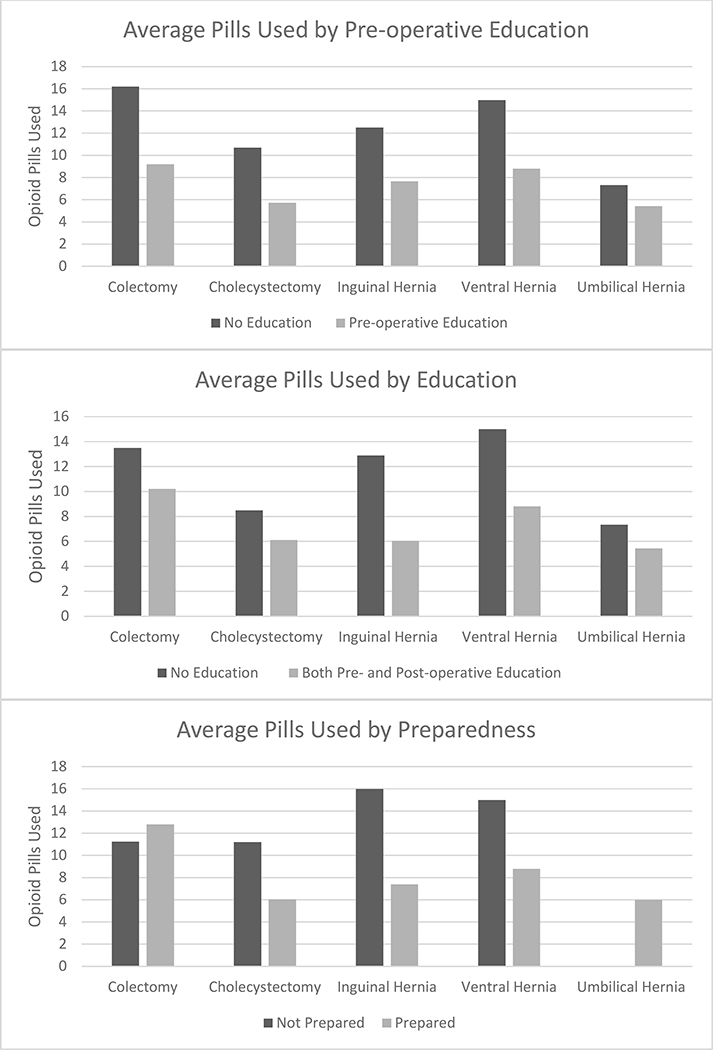

The mean difference in pills used between patients who reported pre-operative education and those who did not varied based on procedure type, with a range of 2 fewer pills for umbilical hernia repair to 30 fewer pills for foregut operations. The association between preparedness and number of pills used also varied by procedure (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Average number of Pills Used according to type of Patient Education provided, and Preparedness as reported by the patient Stratified by the Type of operative procedure.

Footnote: Colectomy n=15, cholecystectomy n=30, inguinal hernia n=20, ventral hernia n=6, umbilical hernia n=11. Foregut operations were not included in these figures due to the small sample size (n=4). There were no patients undergoing umbilical hernia repair who reported feeling unprepared to manage pain.

On multivariable linear regression analysis adjusted for duration of stay, operative procedure, and operative approach, patients who believed they were prepared to manage their pain used on average 9.1 fewer pills than those who believed they were not prepared(p=0.01, see Table 4). Length of stay > 2 days was associated with using 10.9 more pills (p=0.01), while surgical approach did not have a significant effect on pills used (p=0.09).

Table 4.

Mean Difference in Quantity of Pills Used in Adjusted Model

| Pills Used | p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Prepared to manage pain | −9.1 | 0.01 |

| Minimally invasive approach | 6.9 | 0.09 |

| Duration of stay > 2 days | 10.9 | 0.01 |

| Procedure | ||

| Foregut operations | 4.64 | 0.47 |

| Colectomy | −1.11 | 0.82 |

| Cholecystectomy | Reference | |

| Inguinal hernia | 6.06 | 0.18 |

| Ventral hernia | 3.74 | 0.48 |

| Umbilical hernia | 7.81 | 0.18 |

Footnote: Model chosen based on relevant clinical factors, and significant univariate associations. Duration of stay chosen as summary surrogate for morbidity of procedure and post-operative complications that may increase need for opioids..

In another regression model including the same predictors, as well as an interaction term between preparedness and procedure, we found an interaction between the two variables. This finding suggests differing effects of preparedness on number of pills used depending on the type of operative procedure. Subsequently, separate, adjusted regression models for each procedure type revealed fewer pills used for patients reporting preparedness after an inguinal hernia repair(−11.6 pills used; p=0.039) and ventral hernia surgery (−11.5 pills used; p=0.027)..

Disposal

Of the 58 patients who reported they had excess unused opioid pills, 14 (24%) disposed of the excess, and another 20 (35%) stated they intended to dispose of them (Figure 1). ). Only three patients used the in-clinic disposal box, while the remaining 11 patients disposed of their excess at home. While the overall disposal rate was relatively low, it was greater among those who received pre-operative education compared to those who had not “(29.8% vs 0%; P < .05).”

Discussion

Our study demonstrated that patients who felt subjectively prepared to manage their pain used fewer opioid pills postoperatively compared to those who did not feel prepared. Preparedness was 20% greater among patients who received pre-operative education. These findings highlight the importance of patient education and the setting of expectations regarding post-operative pain, particularly in the pre-operative period. By contrast, post-operative education alone was not associated with any increase in patients’ perceived preparedness to manage pain. Importantly, patients who reported both pre- and post-operative education reported the greatest rate of preparedness, which suggests that reinforcement of the education post-operatively can improve pain management.

The preoperative practice of a purposeful discussion of a realistic expectation of postoperative pain and of the safe use of opioids postoperatively represents a departure from traditional practice, because post-operative strategies of pain management are typically discussed only postoperatively. Based on our findings, we strongly suggest that there should be a discussion preoperatively focusing on education and a realistic expectation of the associated postoperative pain in order to decrease the outpatient use of post-operative use of opioids, with the point of discharge being an opportunity for reinforcement rather than the patient’s first exposure to education concerning pain management and counseling concerning disposal of unused opioids.. In addition to timing, the type of provider educating patients is an important factor, because we saw greater rates of preparedness among patients reporting education from their surgeon compared to the provision of education solely from a nurse.

Many previous studies targeting post-operative use of opioids have focused on decreasing the amount of opioids prescribed as their primary outcome of effectiveness without necessarily evaluating the amount of opioids actually used by patients.8–10,19 This approach has resulted in published recommendations regarding procedure-specific, optimal prescribing of opioid needs based on historic data of opioid use.13,20–23 While interventions including patient education have been implemented, stewardship efforts in the house of surgery concerning safe use of opioids have primarily targeted patterns of opioid prescribing by the provixers.9

A systematic review found that clinician-mediated and organizational interventions were the most common methods to decrease postoperative opioid prescribing.19 Interventions included components, such as physician education and training, and decreasing the default quantities of pain prescription in the electronic health record, all of which were effective in encouraging more responsible prescribing; however, patient-mediated interventions yielded inconsistent results. Our study adds a patient-centered approach starting in the pre-operative period and demonstrates the effectiveness of patient education as well as the important role of patient self-efficacy in decreasing patients’ post-use of opioids.

While our intervention was associated with a marked decrease in the use of opioids, our study demonstrated only a moderate increase in appropriate disposal of excess opioids, another important factor in appropriate stewardship by the surgical providers. Only 24% of patients disposed of their excess medications, with only 3 using the in-clinic disposal box. While patients were given educational material regarding opioid safety and disposal, disposal rates remained disappointingly low, and some patients reported being unaware of the in-clinic disposal box. Several possible reasons for these observations, include the lack of clinicians emphasizing the disposal instructions to the extent needed, or that the information about the disposal box as lost in the numerous instructions patients receive during their pre-operative visit. To further assess the effectiveness of the implementation of our approach, we are conducting observations in the clinic to identify and better understand gaps and barriers involved in patients receiving and retaining ll this information. The disappointingly low disposal rate highlights the continued need to focus on removing excess opioids from the community which will require more innovative solutions to address this critical gap in patient education and responsible disposal of unused opioids. Most interventions focus on limiting prescribing quantities to prevent the surplus of unused opioids as the primary means of addressing this problem, but our finding of such a low disposal rate of appropriate disposal highlights the need for more comprehensive approaches. Opioid stewardship should encompass all aspects of a patient’s care from the pre-operative evaluation through postoperative recovery, and approaches that do not “close the loop” may be incomplete.

We acknowledge that our study has several limitations. One limitation is the possibility of survey response bias given our response rate of 28.8%. Patients who were unwilling to answer questions regarding post-operative pain management may have on average had worse (or better) experiences managing their pain. Unfortunately, specific patient characteristics were not available in our dataset to compare responders and non-responders; surgeon and type of procedure were available. While there were no statistically significant differences in type of procedure or surgeon between responders and non-responders in our analysis, there was a wide range of response rate among the individual surgeons (17% – 41%). This is noteworthy, because the greatest response rate was among patients of the surgeon champion of the opioid reduction program at our institution, which likely suggests that surgeon engagement and involvement in opioid stewardship can increase patient participation.

Another limitation is the recall bias inherent in a retrospective survey study. Ascertainment of our outcome may be biased away from the null hypothesis by patients being asked to recall how many pills they have used and whether they disposed of excess pills. Relying on recall in determining our exposure (i.e. recall of pre-operative education, and preparedness to manage pain) can, however, be considered a strength when seen through the lens of effective implementation of our interventions. In other words, although patients may have received pre-operative education, if they did not recall this after their operation, it should be considered a failure of the implementation effectiveness. It is important to note that all patients received pre-operative education in the form of brochures regarding pain management, because this is part of our standardized packet of pre-operative materials; however, the degree to which patients received the one-on-one education and the setting of realistic expectations from their providers is likely variable. On the survey, not all patients reported reading the brochure or having a discussion about pain management, appropriate use of opioids, or safe disposal o f unused opioids. In fact, the proportion of patients reporting pre-operative education ranged from 55% - 83% depending on the provider. When interpreting our results, it is essential to take into account that the extent to which the education was received by patients was variable, even as our efforts at quality improvement were conducted to improve implementation. Although our results are not necessarily reflective of the effectiveness of this intervention being implemented with high fidelity, they do reflect effectiveness in a practical, real-world context.

In conclusion, setting realistic expectations and goals in advance concerning postoperative pain and ensuring that patients feel empowered and prepared to participate in their pain management may be key to achieving minimal opioid use while maintaining adequate pain control. Further work is needed to increase proper disposal of unused opioids.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge nurse manager Denise Dale and nurse educator Chelsea Robinson, as well as all of the nurses, medical assistants, and support staff at the Digestive Health Center for their valuable contributions.

FUNDING/SUPPORT

This work was partially supported by the Digestive Health Foundation. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R34DA044752. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. RK was partially supported by National Institutes of Health grant #5T32HL094293.

Footnotes

COI/DISCLOSURE: The authors report no conflicts of interest

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Scholl L, Seth P, Kariisa M, Wilson N, Baldwin G. Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths - United States, 2013–2017. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. January 4 2018;67(5152):1419–1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brummett CM, Waljee JF, Goesling J, et al. New Persistent Opioid Use After Minor and Major Surgical Procedures in US Adults. JAMA surgery. June 21 2017;152(6):e170504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hill MV, McMahon ML, Stucke RS, Barth RJ, Jr., Wide Variation and Excessive Dosage of Opioid Prescriptions for Common General Surgical Procedures. Annals of surgery. April 2017;265(4):709–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lipari RN, Hughes A. How People Obtain the Prescription Pain Relievers They Misuse The CBHSQ Report. Rockville (MD)2013:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sun EC, Darnall BD, Baker LC, Mackey S. Incidence of and Risk Factors for Chronic Opioid Use Among Opioid-Naive Patients in the Postoperative Period. JAMA internal medicine. September 1 2016;176(9):1286–1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bicket MC, Long JJ, Pronovost PJ, Alexander GC, Wu CL. Prescription Opioid Analgesics Commonly Unused After Surgery: A Systematic Review. JAMA surgery. November 1 2017;152(11):1066–1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hallway A, Vu J, Lee J, et al. Patient Satisfaction and Pain Control Using an Opioid-Sparing Postoperative Pathway. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. April 26 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howard R, Waljee J, Brummett C, Englesbe M, Lee J. Reduction in Opioid Prescribing Through Evidence-Based Prescribing Guidelines. JAMA surgery. March 1 2018;153(3):285–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hill MV, Stucke RS, McMahon ML, Beeman JL, Barth RJ, Jr., An Educational Intervention Decreases Opioid Prescribing After General Surgical Operations. Annals of surgery. March 2018;267(3):468–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiu AS, Jean RA, Hoag JR, Freedman-Weiss M, Healy JM, Pei KY. Association of Lowering Default Pill Counts in Electronic Medical Record Systems With Postoperative Opioid Prescribing. JAMA surgery. November 1 2018;153(11):1012–1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shah A, Hayes CJ, Martin BC. Factors Influencing Long-Term Opioid Use Among Opioid Naive Patients: An Examination of Initial Prescription Characteristics and Pain Etiologies. The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society. November 2017;18(11):1374–1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brat GA, Agniel D, Beam A, et al. Postsurgical prescriptions for opioid naive patients and association with overdose and misuse: retrospective cohort study. Bmj. January 17 2018;360:j5790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Illinois Surgical Quality Improvement Collaborative. Opioid Reduction Initiatives. 2017; https://www.isqic.org/opioid-reduction-initiatives, 2019.

- 14.Nooromid MJ, Mansukhani NA, Deschner BW, et al. Surgical interns: Preparedness for opioid prescribing before and after a training intervention. American journal of surgery. February 2018;215(2):238–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cleeland CS, Gonin R, Hatfield AK, et al. Pain and its treatment in outpatients with metastatic cancer. The New England journal of medicine. March 3 1994;330(9):592–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cleeland CS, Nakamura Y, Mendoza TR, Edwards KR, Douglas J, Serlin RC. Dimensions of the impact of cancer pain in a four country sample: new information from multidimensional scaling. Pain. October 1996;67(2–3):267–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mendoza TR, Chen C, Brugger A, et al. Lessons learned from a multiple-dose post-operative analgesic trial. Pain. May 2004;109(1–2):103–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cleeland CS. The Brief Pain Inventory User Guide. 2009; https://www.mdanderson.org/research/departments-labs-institutes/departments-divisions/symptom-research/symptom-assessment-tools/brief-pain-inventory.html. Accessed 9/4/2019.

- 19.Wetzel M, Hockenberry J, Raval MV. Interventions for Postsurgical Opioid Prescribing: A Systematic Review. JAMA surgery. October 1 2018;153(10):948–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Overton HN, Hanna MN, Bruhn WE, et al. Opioid-Prescribing Guidelines for Common Surgical Procedures: An Expert Panel Consensus. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. October 2018;227(4):411–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scully RE, Schoenfeld AJ, Jiang W, et al. Defining Optimal Length of Opioid Pain Medication Prescription After Common Surgical Procedures. JAMA surgery. January 1 2018;153(1):37–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Michigan Opioid Prescribing Engagement Network. Prescribing Recommendations. 2019; https://opioidprescribing.info/, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thiels CA, Ubl DS, Yost KJ, et al. Results of a Prospective, Multicenter Initiative Aimed at Developing Opioid-prescribing Guidelines After Surgery. Annals of surgery. September 2018;268(3):457–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.