Abstract

Background

Limited research examines depressive symptoms, alcohol use, and social support among HIV-infected people who inject drugs.

Objectives

Using longitudinal data, we investigated whether perceived social support moderates the relationship between depressive symptoms and alcohol use among HIV-infected men who inject drugs in Vietnam.

Methods

Data were collected from participants (N=455; mean age 35 years) in a four-arm randomized controlled trial in Thai Nguyen, Vietnam. Data were collected at baseline, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months with 94% retention excluding dead (N=103) or incarcerated (N=37) participants. Multilevel growth models were used to assess whether: (1) depressive symptoms predict when risk of alcohol use is elevated (within-person effects); (2) depressive symptoms predict who is at risk for alcohol use (between-person effects); and (3) within- and between-person perceived social support moderates the depressive symptoms-alcohol relationship.

Results

Participants reported high but declining levels of depressive symptoms and alcohol use. Participants with higher depressive symptoms drank less on average (B=−0.0819, 95% CI −0.133, −0.0307), but within-person, a given individual was more likely to drink when they were feeling more depressed than usual (B=0.136, 95% CI 0.0880, 0.185). The positive relationship between within-person depressive symptoms and alcohol use grew stronger at higher levels of within-person perceived social support.

Conclusions

HIV-infected men who inject drugs have increased alcohol use when they are experiencing higher depressive symptoms than usual, while those with higher average depressive symptoms over time report less alcohol use. Social support strengthens the positive relationship between within-person depressive symptoms and alcohol use.

Keywords: Depression, alcohol use, social support, HIV/AIDS, people who inject drugs, Vietnam

Introduction

People living with HIV (PLHIV) have a higher prevalence of alcohol abuse compared to the general population (Scott-Sheldon et al., 2013). Alcohol consumption among PLHIV results in poor health outcomes, including premature mortality (Bryant, Nelson, Braithwaite, & Roach, 2010), decreased viral suppression (Chander, Lau, & Moore, 2006), increased liver damage among those co-infected with hepatitis C virus (Braithwaite & Bryant, 2010), and reduced antiretroviral treatment (ART) adherence (Chander et al., 2006; Do, Dunne, Kato, Pham, & Nguyen, 2013; Hendershot, Stoner, Pantalone, & Simoni, 2009; Tran, Nguyen, Do, Nguyen, & Maher, 2014).

Most alcohol and depression research has found that increased alcohol use leads to increased depressive symptoms (Longmire-Avital, Holder, Golub, & Parsons, 2012; Palfai et al., 2014; Pence et al., 2008). In response to experiencing depressive symptoms, individuals may use substances as a maladaptive coping strategy (Glanz, Rimer, & Viswanath, 2008; Lazarus & Folkman, 1987). Drinking to cope with negative emotions can significantly predict drinking quantity and alcohol dependence status among PLHIV (Elliott, Aharonovich, O’Leary, Wainberg, & Hasin, 2014).

Social support may moderate the relationship between depressive symptoms and alcohol use (Mizuno, Purcell, Dawson-Rose, Parsons, & Team, 2003; Pence et al., 2008), offering a promising leverage point to reduce alcohol use. Empirical and theoretical evidence suggests that individuals with greater social support will be less likely to use maladaptive coping strategies, such as substance use, in response to experiencing depressive symptoms (Glanz et al., 2008; Lazarus & Folkman, 1987). However, social isolation and depressive symptoms are highly correlated (Ge, Yap, Ong, & Heng, 2017; Hussong et al., 2018), demonstrating the complex relationship between depressive symptoms, social support, and alcohol use and the need for further analysis using longitudinal research.

Hazardous drinking is prevalent among PLHIV in Vietnam; studies have found that 20–30% of HIV-infected patients reported hazardous or harmful drinking in Vietnam (Levintow et al., 2018; Tran et al., 2013). However, contrary to similar research conducted in other settings, a cross-sectional study with HIV-infected men who inject drugs in Vietnam found that people who drank alcohol were less likely to have severe depressive symptoms than those who drank no alcohol (Levintow et al., 2018). This divergence in findings may be explained by sociocultural norms around alcohol use. In Vietnam, alcohol use is strongly encouraged through cultural practices and informal and formal social events, especially for men (Hershow et al., 2018; Lincoln, 2016; Luu, Nguyen, & Newman, 2014; Tran et al., 2013). Men’s alcohol use is seen as closely tied to their masculinity and is a regular part of daily social and family life and professional networking (Lincoln, 2016). It is seen as disrespectful for a man to refuse a drink at a social event (Hershow et al., 2018; Lincoln, 2016). For men living with HIV, social activities involving alcohol may act as a key access point for social support (Hershow et al., 2018). Qualitative data suggest that men living with HIV who experience depressive symptoms tend to lose access to social support by isolating themselves, which leads to a reduction in alcohol use (Hershow et al., 2018).

The longitudinal relationship between depressive symptoms and alcohol use has not been examined quantitatively among HIV-infected men who inject drugs in Vietnam. Investigating this relationship over time is particularly important due to the novel finding in a cross-sectional study demonstrating that alcohol use and depressive symptoms are negatively associated in this population (Levintow et al., 2018). Since cross-sectional studies cannot establish temporality and can only examine between-person effects (i.e., mean differences in alcohol use between individuals), there is a dearth of research examining the following: (1) the within-person effects of depressive symptoms on alcohol use (i.e., the effect of an individual’s change in depressive symptoms at one time point on alcohol use at the same time point); and (2) the temporality of the relationship between depressive symptoms and alcohol use (i.e., whether changes in depressive symptoms precede changes in alcohol use). Further, there is limited research assessing whether level of social support influences the strength or direction of the relationship between depressive symptoms and alcohol use.

In this paper, we will examine the relationship between depressive symptoms and alcohol use over time and determine whether perceived social support influences the relationship. It is critical to conduct this research with HIV-infected men who inject drugs as alcohol use is associated with injection drug use and the co-occurrence of alcohol and injection drug use may exacerbate individuals’ low engagement with the HIV treatment cascade (Lima et al., 2014; Mugavero et al., 2006; Peretti-Watel, Spire, Lert, Obadia, & Group, 2006; Williams et al., 2016). Thus, our findings will help inform recommendations on intervention strategies for alcohol reduction to improve HIV-related outcomes among a highly marginalized group.

Materials and methods

Study design

The study was conducted in Thai Nguyen, a semi-urban mountainous province located 75 km north of Hanoi. Thai Nguyen has the highest HIV prevalence among people who inject drugs (PWID; 34%) in Vietnam, almost all of whom are male (Vietnam AIDS Response Progress Report 2014: Following up the 2011 Political Declaration on HIV/AIDS, 2014). In the study, we evaluated a multi-level HIV prevention intervention for HIV-positive PWID using a four-arm randomized controlled trial (RCT). Participants randomized to Arm 1 received the standard of care comprising a pre- and post-test HIV testing and counseling session. Participants randomized to Arm 2 received structural-level HIV and injection drug use (IDU) stigma reduction programs, including a two-part video and six HIV education sessions delivered by community mobilization voluteers. Participants randomized to Arm 3 received individual-level programs on HIV knowledge and coping strategies for managing HIV, including two HIV post-test counseling sessions, two skill-building support groups, and one optional dyad session with a supporter. Participants randomized to Arm 4 received both structural- and individual-level activities. Details of the trial and primary outcomes are reported elsewhere (Go et al., 2017; Go et al., 2015).

Recruitment

From July 2009-January 2011, participants were recruited using snowball sampling by a team of seven recruiters who were former or current drug users (Go et al., 2017; Go et al., 2015). Snowball sampling enabled our study team to access a hard-to-reach population, build trust and rapport, and protect privacy. Recruiters approached their current or former drug networks privately and distributed brochures and answered questions about the study. Interested subjects were accompanied or referred to the project office to be screened for eligibility. Based on the goal of the RCT to evaluate the effectiveness of HIV prevention interventions on HIV-related outcomes, inclusion criteria included: HIV-positive diagnosis confirmed through testing by study staff; able and willing to bring in an injecting network member for screening; male; 18 years of age or older; had sex in previous six months; injected drugs in the previous six months; and planned to be a resident in Thai Nguyen for the next 24 months. Exclusion criteria included: unwilling to provide locator information or currently participating in other HIV prevention interventions. For this analysis, recruited injecting network partners were not included as they were HIV-uninfected.

Data collection procedures

Data on demographics, sexual behavior, substance use, injection risk behavior, psychosocial factors, and HIV and IDU stigma were collected from enrolled participants (N=455) at baseline, 6-month, 12-month, 18-month, and 24-month follow-up through face-to-face interviews with a study staff member in a private room at the ART clinic. Participants were reimbursed 75,000 Vietnamese Dong (VND), the equivalent of 3.50 U.S. Dollars (USD), at each visit and 5,000 VND (0.23 USD) for each kilometer traveled. Overall retention at 24 months excluding those who died (N=103/455; 22.6%) or were incarcerated (N=37/455; 8.1%) was 94%.

The study protocol received ethical approval from the Institutional Review Boards at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and the Thai Nguyen Center for Preventive Medicine.

Key measures

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were measured using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depressive symptoms Scale (CES-D). The CES-D is a 20-item screening tool that measures depressive symptoms experienced over the past week (Radloff, 1977); CES-D is widely used and has been shown to be valid and reliable when used in Vietnam (Leggett, Zarit, Nguyen, Hoang, & Nguyen, 2012; Thai, Jones, Harris, & Heard, 2016). Individuals with a CES-D score above 16 have probable moderate depressive symptoms and those with a CES-D score above 23 have probable severe depressive symptoms (Thai et al., 2016). In this analysis, the depressive symptoms variable was treated as continuous.

Perceived social support

Perceived social support was measured using a modified version of the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) social support scale (Sherbourne & Stewart, 1991). The 19-item scale consists of four subscales: (1) emotional/informational support; (2) tangible support; (3) positive social interaction; and (4) affectional support. Participants were asked how often each kind of support is available if they needed it; response options included: All of the time, Most of the time, Some of the time, A little of the time, and None of the time. Possible scores for each subscale ranged from zero to 100. In this analysis, an overall perceived social support score was calculated for each participant by summing the scores for each subscale; higher scores indicate greater perceived social support. The MOS social support scale has been validated with the study population and all four subscales have been found to be reliable (Go et al., 2016).

Alcohol use

Alcohol use was measured using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT). The AUDIT is a 10-item screening tool and widely used measure to identify problem drinking (Babor, Higgins-Biddle, Saunders, & Monteiro, 2001). Males with an AUDIT score greater or equal to eight screen positive for hazardous alcohol use (range=0–40). AUDIT has been used in previous research in rural Vietnam and found to be valid and reliable (Giang, Allebeck, Spak, Van Minh, & Dzung, 2008; Giang, Spak, Dzung, & Allebeck, 2005). In this analysis, the alcohol use variable was treated as continuous to avoid loss of meaningful information.

Covariates

Covariates were selected based on empirical or theoretical evidence demonstrating that they were potential confounders of the association between alcohol use and depressive symptoms (Engel, 1980). Demographic variables, including age (Liu et al., 2016; Nanni, Caruso, Mitchell, Meggiolaro, & Grassi, 2015; Silverberg et al., 2018), employment status (Liu et al., 2016; Nanni et al., 2015; Tran et al., 2013), and marital status (Levintow et al., 2018; Tran et al., 2013); other substance use factors, including injection drug use (Levintow et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2016; Nanni et al., 2015; Silverberg et al., 2018), non-injection drug use (Liu et al., 2016; Nanni et al., 2015; Silverberg et al., 2018), and cigarette smoking (Bultum, Yigzaw, Demeke, & Alemayehu, 2018; Levintow et al., 2018); and psychosocial factors, including HIV stigma (Earnshaw, Smith, Cunningham, & Copenhaver, 2015; Hershow et al., 2018; Kane et al., 2019; Lunze et al., 2017; Tesfaw et al., 2016) and IDU stigma (Earnshaw et al., 2015; Hershow et al., 2018) were collected via self-report. Higher HIV and IDU stigma scores indicate greater HIV and IDU stigma. Data on intervention arm assignment, mortality, and incarceration during study period were also examined in analysis.

Data analysis

For the analysis, multilevel modeling was used to disaggregate and examine both the within- and between-person effects of depressive symptoms on trajectories of alcohol use. This approach facilitates investigation on whether depressive symptoms predicts when risk of harmful alcohol use is elevated (within-person effects) and/or whether depressive symptoms predicts who is at risk for harmful alcohol use (between-person effects).

The longitudinal effects of depressive symptoms on alcohol use patterns were estimated using multilevel growth models. The models were specified at two levels in which wave of data collection (level one) was nested within individuals (level two). This approach allowed for the separation of the total variance in alcohol use into within-person variation (variation in an individual’s alcohol use over time) and between-person variation (variation across individuals in mean alcohol use). A random intercept and slope model was used, meaning that participants were treated as random effects to allow for variation in individuals’ initial level of alcohol use (the intercept) and linear change in alcohol use over time (the slope). All covariate effects were treated as fixed effects (i.e., no random slope was estimated).

Appropriate centering strategies were used with all variables included in the analysis (Curran & Bauer, 2011). The variable for wave of data collection was re-coded to start at zero so that the intercept represents the average level of alcohol use at baseline. The within-person depressive symptoms and perceived social support variables were person-mean centered and person-mean depressive symptoms and person-mean perceived social support variables were grand-mean centered. Dichotomous or trichotomous covariates were dummy coded and age (years) was grand-mean centered. HIV and IDU stigma variables were treated as time-invariant (level two) as a previous study paper showed no significant changes over time (Go et al., 2015); these two variables were grand-mean centered after the person-mean for each was calculated. Multilevel multiple imputation (MI) was conducted to address missingness in the data following the model from Enders et al. (Enders, Mistler, & Keller, 2016). Missed observations were not imputed for missingness due to death (N=103) or incarceration (N=50) throughout the longitudinal study. MI was carried out using joint imputation on Mplus (Enders et al., 2016).

Analysis was conducted in four major steps using SAS 9.4. First, unconditional growth models were tested to assess whether a linear functional form fit the shape of change over the five waves of data collection and the covariance structure of the unconditional trajectories of alcohol use. The interaction of depressive symptoms with wave of data collection was also tested to establish the proper functional form; this interaction term was not included because it was not significant and not hypothesized. Next, the within- and between-person depressive symptoms variables were added to the model to test the main effects for the within- and between-person depressive symptoms on alcohol use. Then, the conditional growth model was adjusted for covariates. Finally, two-way interactions were tested among within- and between-person perceived social support and within- and between-person depressive symptoms variables. Any non-significant interactions were removed from the final model.

Results

Descriptive statistics

At baseline, the mean age of participants (N=455) was 35.22 years (standard deviation [SD]=6.30; Table 1). The majority of participants were employed part- or full-time (N=397; 87.25%). Almost half of participants were married or cohabitating (N=215; 47.25%), with the remainder being single (N=175; 38.46%) or widowed, divorced, or separated (N=65; 14.29%). About half of participants reported injecting heroin daily (N=224; 50.56%) and most reported smoking cigarettes daily (N=391; 85.93%), while 8.57% of participants reported using non-injection heroin in the previous three months (N=39). The average scores for the psychosocial factors were the following: mean HIV stigma score was 29.69 (SD=4.06; range=14–44) and the mean IDU stigma score was 18.72 (SD=2.79; range=9–28).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the sample at baseline (N=455)

| Mean (SD) or N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Demographic Factors | |

| Mean age in years (range 19–60) | 35.22 (6.30) |

| Employment status Unemployed or unable to work Working full-time or part-time |

58 (12.75) 397 (87.25) |

| Marital status Single Widowed, divorced, or separated Married or cohabitating |

175 (38.46) 65 (14.29) 215 (47.25) |

| Other Substance Use Factors | |

| Proportion that inject heroin dailya | 224 (50.56) |

| Proportion that used non-injectable heroin in last 3 months | 39 (8.57) |

| Proportion that smoke cigarettes daily | 391 (85.93) |

| Psychosocial Factors | |

| Mean HIV stigma score (range 14–44) | 29.69 (4.06) |

| Mean injection drug use stigma score (range 9–28) | 18.72 (2.79) |

Frequency of heroin use was missing for 12 participants (3%)

Note: SD=standard deviation

At baseline, the mean AUDIT score was 4.44 (SD=5.19), with 20% of participants screening positive for harmful alcohol use (>8) (Table 2). At 24-month follow-up, the mean AUDIT score decreased to 3.34 (SD=4.51); the proportion of participants screening positive for harmful alcohol use remained the same. At baseline, the mean CES-D score was 21.32 (SD=10.51), with 44% of participants reporting severe depressive symptoms. At 24-month follow-up, the mean CES-D score decreased to 15.88 (SD=7.39), with half as many participants reporting severe depressive symptoms (22%). The mean perceived social support score was 274.67 (SD=83.31; range=0–400) at baseline and decreased slightly to 273.78 (SD=85.33; range=0–400) at 24-month follow-up.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics by assessment wave*

| Variable | Baseline N=455 | 6-month follow-up N=377 | 12-month follow-up N=327 | 18-month follow-up N=292 | 24-month follow-up N=297 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | % | Mean (SD) | % | Mean (SD) | % | Mean (SD) | % | Mean (SD) | % | |

| Alcohol use | 4.44 (5.19) | 20 | 3.46 (4.62) | 17 | 3.92 (5.05) | 21 | 3.38 (4.50) | 17 | 3.34 (4.51) | 20 |

| Depressive symptoms | 21.32 (10.51)a | 44 | 20.88 (9.63) | 45 | 19.11 (8.91) | 35 | 17.18 (8.23) | 28 | 15.88 (7.39) | 22 |

| Perceived social support | 274.67 (83.31) | -- | 278.34 (82.83) | -- | 277.96 (82.54) | -- | 268.00 (80.93) | -- | 273.78 (85.33) | -- |

Mean scores were calculated prior to conducting multiple imputation and to centering the variables. Percentages were calculated as the proportion of the participants reporting severe depressive symptoms (CES-D ≥ 23) or harmful alcohol use (AUDIT ≥ 8) at each assessment.

Missing data: 1 participant missing data for CES-D at baseline

Note: SD=standard deviation; CES-D=Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depressive symptoms Scale; AUDIT=Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test

Trajectories of alcohol use: Unconditional growth model

There was wide variability in alcohol use at baseline and over the course of follow-up (Table 3). The best fitting unconditional model for alcohol use included a random intercept and linear slope. There was significant variance between men in mean levels of alcohol use at baseline (intercept estimate=4.36, 95% Confidence Interval [CI] 3.89, 4.84). Concordant with mean trends, there was also a significant linear decrease in the predicted mean trajectory of alcohol use over the five waves of data collection (B=−0.292, 95% CI −0.465, −0.119).

Table 3.

Results for the multilevel growth models of the patterns of alcohol usea

| Parameter | Unconditional Model B coefficient (95% CI) |

Unadjusted Conditional Model B coefficient (95% CI) | Adjusted Conditional Modelb B coefficient (95% CI) | Adjusted Conditional Model with Interaction Term Addedb B coefficient (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed Effects Intercept Wave of data collection |

4.36 (3.89, 4.84) −0.292 (−0.465, −0.119) |

4.00 (3.54, 4.45) −0.109 (−0.292, 0.073) |

3.03 (2.00, 4.06) −0.0715 (−0.255, 0.112) |

2.86 (1.84, 3.87) −0.149 (−0.320, 0.0224) |

| Depressive Symptoms Within-person (WP) Between-person (BP) |

--- --- |

0.162 (0.105, 0.218) −0.0945 (−0.141, −0.0483) |

0.136 (0.0880, 0.185) −0.0819 (−0.133, −0.0307) |

0.124 (0.0836, 0.164) −0.0887 (−0.139, −0.0380) |

| Perceived Social Support WP BP |

--- --- |

--- --- |

0.0128 (0.00923, 0.0164) 0.00572 (−0.00041, 0.0119) |

0.0145 (0.0110, 0.0179) 0.00638 (0.00032, 0.0124) |

| WP Depressive Symptoms X WP Perceived Social Support | --- | --- | --- | 0.00176 (0.00101, 0.00250) |

| Relative Quality of Models Average AIC Average BIC |

11406.4 11419.6 |

11288.9 11304.6 |

11171.1 11186.1 |

11091.1 11107.4 |

The covariance parameters for the random intercept, random linear slope for wave of data collection, covariance between intercept and slope, and residual variance were modeled but not included in the table because the estimates and standard errors for the aggregated values were not generated by the multiple imputation procedure.

Adjusting for intervention arm, age, employment status, marital status, injection drug use, non-injection drug use, cigarette smoking, HIV stigma, and injection drug use stigma.

Note: AIC=Akaike information criterion; BIC=Bayesian information criterion

Main effects of depressive symptoms on alcohol use trajectories

Unadjusted conditional growth model

Within- and between-person effects of depressive symptoms AUDIT score were observed (Table 3). A one unit increase in within-person depressive symptoms was associated with a 0.162 unit increase in AUDIT score (95% CI 0.105, 0.218). In contrast, a one unit increase in between-person depressive symptoms was associated with a −0.0945 unit decrease in AUDIT score (95% CI −0.141, −0.0483).

Adjusted conditional growth model

When we controlled for potential confounders, our findings were similar (Table 3). In the adjusted model, the effect of wave of data collection on AUDIT score was non-significant (B=−0.0715, 95% CI −0.255, 0.112). Within- and between-person effects of depressive symptoms AUDIT score remained significant (Within-person: B=0.136, 95% CI 0.0880, 0.185; Between-person: B=−0.0819, 95% CI −0.133, −0.0307). Within-person perceived social support was significantly associated with AUDIT score (B=0.0128, 95% CI 0.00923, 0.0164), while between-person perceived social support was not found to be significantly associated with AUDIT score (B=0.00572, 95% CI −0.00041, 0.0119).

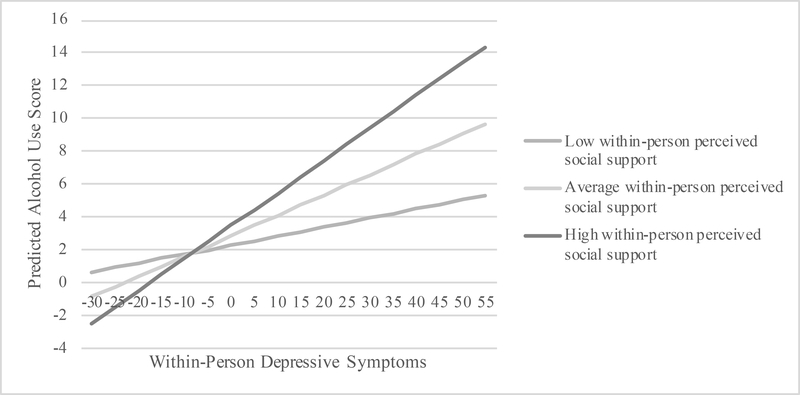

Depressive symptoms and perceived social support associated with alcohol use: Adjusted conditional growth model with interaction term added

Perceived social support moderated the relationship between depressive symptoms and alcohol use (Table 3). The interaction term for between-person depressive symptoms by between-person perceived social support was found to be non-significant at p<0.05 and thus was not included in the final model. The interaction between within-person depressive symptoms by within-person perceived social support on alcohol use was small, but significant. The interaction was probed at low, medium, and high levels of within-person perceived social support in Figure 1 to visualize these relationships. Predicted alcohol use scores were graphed for minimum to maximum within-person depressive symptoms and within-person perceived social support scores at 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles. The slopes representing the effects of within-person depressive symptoms on alcohol use for those with low (B=0.0548, Standard Error [SE]=0.0191), average (B=0.124, SE=0.0155), and high within-person perceived social support (B=0.198, SE=0.0177) were all significant at p<0.05. Results showed that those with lower perceived social support than average had a weaker positive relationship between within-person depressive symptoms and alcohol use, while those with average and higher perceived social support than average had stronger positive relationships between within-person depressive symptoms and alcohol use.

Figure 1.

Estimated alcohol use as a function of within-person depressive symptoms and within-person perceived social support at low (25th percentile), average (50th percentile), and high (75th percentile) levels of the interaction

Discussion

This study examined the associations between depressive symptoms and perceived social support on alcohol use using longitudinal data. Results demonstrated that both depressive symptoms and alcohol use are highly prevalent among HIV-infected men who inject drugs in Thai Nguyen, Vietnam and are higher compared to studies conducted in other global settings with men living with HIV (Ha et al., 2018; Seth et al., 2014). Results also showed the complex interplay between depressive symptoms, perceived social support, and alcohol use in this population and setting. Findings suggest that individuals who experience depressive symptoms increase their alcohol use under certain circumstances and decrease their alcohol use under others. Coping responses to depressives symptoms may differ depending on the duration and timing of the experience of depressive symptoms. These varied coping responses may be explained by Vietnamese sociocultural norms around alcohol use that intertwine social drinking and social support as well as drinking avoidance and social isolation (Hershow et al., 2018; Lincoln, 2016).

Findings showed significant within- and between-person effects of depressive symptoms on alcohol use, though in different directions. For between-person effects, we found that individuals with higher average depressive symptoms over the course of the study had lower alcohol use. For within-person effects, we found that individuals with higher depressive symptoms than usual at one time point had increased alcohol use at that same time point. These results demonstrate that HIV-infected men who inject drugs may employ different coping strategies when experiencing depressive symptoms over a longer period of time as compared to experiencing heightened depressive symptoms at one point in time. Notably, the magnitude of the significant within- and between-person effects of depressive symptoms on alcohol use were modest. While both depressive symptoms and alcohol use decreased over the course of the study, the reductions in depressive symptoms may not have been substantial enough to be associated with clinically meaningful changes in alcohol use. Interventions addressing the relationship between depressive symptoms and alcohol use may lead to clinically meaningful reductions.

Individuals with higher average depressive symptoms over the course of the study had decreased alcohol use. This finding suggests that HIV-infected men who inject drugs may not use alcohol as a coping strategy when experiencing depressive symptoms over time. A possible explanation for this novel finding is that participants may socially isolate themselves in response to experiencing depressive symptoms (Hershow et al., 2018). Alternatively, these participants may experience social isolation due to their marginalized status in the community (Salter et al., 2010), leading to depressive symptoms (Ge et al., 2017; Rapier, McKernan, & Stauffer, 2019; Taylor, Taylor, Nguyen, & Chatters, 2018). Since most alcohol consumption in Vietnam takes place at social events (Lincoln, 2016), social isolation may result in reductions in alcohol use (Hershow et al., 2018). Future research should examine the role that social isolation plays in the inverse relationship between depressive symptoms and alcohol use over time in this population.

Individuals with higher depressive symptoms than usual had higher alcohol use. This finding suggests that HIV-infected men who inject drugs may initially respond to heightened depressive symptoms with the use of alcohol as a maladaptive coping strategy or as a form of self-medication. Similar results have been found in other studies (Elliott et al., 2014; Gottfredson & Hussong, 2013; Hussong, 2007; Hussong, Jones, Stein, Baucom, & Boeding, 2011).

In our study, participants who reported higher perceived social support than average at one time point were more likely to report increased alcohol use at the same time point. The direct effect of perceived social support on alcohol use suggests that receiving social support may be tied to social drinking, which is supported by ethnographic research on the drinking culture in Vietnam (Lincoln, 2016). Due to the integral role that alcohol plays in most social interactions for men (Lincoln, 2016), men living with HIV may mainly access social support by drinking with friends and family (Hershow et al., 2018). The link between social drinking and social support may be heightened for HIV-infected men who inject drugs due to experiences of HIV and IDU stigma; as a result, they may be particularly vulnerable to social pressure to drink to gain social acceptance (Go et al., 2015; Hershow et al., 2018; Rapier et al., 2019; Salter et al., 2010). Social pressure to drink alcohol has been shown to be a common drinking motive among PLHIV in other settings (Elliott et al., 2014).

Our moderation analyses further suggest that social support and social drinking may be intertwined. In the final model, we found that the positive relationship between depressive symptoms and alcohol use grew stronger at higher levels of perceived social support. If HIV-infected men who inject drugs are experiencing higher depressive symptoms and receiving lower social support than average, it may mean that they are not drinking socially as often and thus have a weaker association between depressive symptoms and alcohol use. Conversely, individuals who are experiencing higher depressive symptoms and receiving higher social support than average may be drinking with friends or family more often, resulting in a stronger positive association between depressive symptoms and alcohol use. As our results do not provide sufficient evidence that social drinking is equated with social support, further research is needed to understand how this population accesses social support and the extent of overlap between social drinking and social support.

There are several important limitations to note. Snowball sampling was used to recruit participants. Snowball samples are not statistically representative of the source population (HIV-infected men who inject drugs in Vietnam), given that participants were not randomly sampled. Thus, the generalizability of the findings from the sample to the population of HIV-infected men who inject drugs in Vietnam is limited. Still, the study provides important insights into the longitudinal relationship between depressive symptoms, perceived social support, and alcohol use in a population that is highly stigmatized and difficult to reach. Additionally, all key measures were collected via self-report, which may mean that there is the possibility of social desirability bias. However, the study team investigated the possible presence of self-reporting bias and did not find evidence that it influenced results (Go et al., 2013). The interventions evaluated in the RCT may have influenced whether or not participants drank alcohol in response to changes in mood or social context. However, in exploratory analyses, the effect of depressive symptoms on alcohol use was not found to signficantly differ across trial arms (Supplemental Table 1). Finally, the high mortality rate during the study (103/455) is a notable limitation (Go et al., 2017), as individuals who died may represent a sub-group with particularly high levels of alcohol use and/or depressive symptoms. However, in exploratory analyses, interaction effects of depressive symptoms by mortality and wave of data collection by mortality on alcohol use were both found to be non-significant.

Conclusions

This longitudinal analysis contributes to an important research gap on alcohol use, social support, and depressive symptoms among men living with HIV in global settings. Findings suggest that HIV-infected men who inject drugs may use alcohol as a form of self-medication at times when they are experiencing increased depressive symptoms, while those with higher average depressive symptoms than others may socially isolate themselves, thus reducing their alcohol use. Further, social support has influence on the strength of the relationship between depressive symptoms and alcohol use. This finding suggests that social support may shape the strategies used by HIV-infected men who inject drugs to cope with changes in depressive symptoms.

HIV-infected men who inject drugs need support to treat the co-occurrence of depressive symptoms and alcohol use to prevent negative HIV-related outcomes, such as poor ART adherence. Mental health and alcohol reduction services should be integrated into HIV treatment and care in Vietnam. In particular, HIV-infected men who inject drugs should be counseled on how to refuse alcohol despite strong social pressure to drink, and how to use healthy coping strategies when experiencing depressive symptoms, instead of resorting to social isolation or alcohol use. Further, HIV-infected men who inject drugs should be encouraged to identify and build social support outside of drinking contexts.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (1 R01 DA022962-01). This work was also supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (T32-AI007001).

Footnotes

Disclosure statement: No conflicts of interest.

References

- Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, & Monteiro MG (2001). The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test Guidelines for Use in Primary Care. [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite RS, & Bryant KJ (2010). Influence of alcohol consumption on adherence to and toxicity of antiretroviral therapy and survival. Alcohol Res Health, 33(3), 280–287. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant KJ, Nelson S, Braithwaite RS, & Roach D (2010). Integrating HIV/AIDS and alcohol research. Alcohol Res Health, 33(3), 167–178. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bultum JA, Yigzaw N, Demeke W, & Alemayehu M (2018). Alcohol use disorder and associated factors among human immunodeficiency virus infected patients attending antiretroviral therapy clinic at Bishoftu General Hospital, Oromiya region, Ethiopia. PLoS One, 13(3), e0189312. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0189312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chander G, Lau B, & Moore RD (2006). Hazardous alcohol use: a risk factor for non-adherence and lack of suppression in HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 43(4), 411–417. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000243121.44659.a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, & Bauer DJ (2011). The disaggregation of within-person and between-person effects in longitudinal models of change. Annu Rev Psychol, 62, 583–619. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do HM, Dunne MP, Kato M, Pham CV, & Nguyen KV (2013). Factors associated with suboptimal adherence to antiretroviral therapy in Viet Nam: a cross-sectional study using audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI). BMC Infect Dis, 13, 154. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earnshaw VA, Smith LR, Cunningham CO, & Copenhaver MM (2015). Intersectionality of internalized HIV stigma and internalized substance use stigma: Implications for depressive symptoms. J Health Psychol, 20(8), 1083–1089. doi: 10.1177/1359105313507964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott JC, Aharonovich E, O’Leary A, Wainberg M, & Hasin DS (2014). Drinking motives as prospective predictors of outcome in an intervention trial with heavily drinking HIV patients. Drug Alcohol Depend, 134, 290–295. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.10.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK, Mistler SA, & Keller BT (2016). Multilevel multiple imputation: A review and evaluation of joint modeling and chained equations imputation. Psychol Methods, 21(2), 222–240. doi: 10.1037/met0000063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel GL (1980). The clinical application of the biopsychosocial model. Am J Psychiatry, 137(5), 535–544. doi: 10.1176/ajp.137.5.535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge L, Yap CW, Ong R, & Heng BH (2017). Social isolation, loneliness and their relationships with depressive symptoms: A population-based study. PLoS One, 12(8), e0182145. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giang KB, Allebeck P, Spak F, Van Minh H, & Dzung TV (2008). Alcohol use and alcohol consumption-related problems in rural Vietnam: an epidemiological survey using AUDIT. Subst Use Misuse, 43(3–4), 481–495. doi: 10.1080/10826080701208111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giang KB, Spak F, Dzung TV, & Allebeck P (2005). The use of audit to assess level of alcohol problems in rural Vietnam. Alcohol Alcohol, 40(6), 578–583. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glanz K, Rimer B, & Viswanath K (2008). Health behavior and Health Education: Theory, research, and practice (Fourth ed. ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Go VF, Frangakis C, Le Minh N, Ha TV, Latkin CA, Sripaipan T, … Quan VM (2017). Increased Survival Among HIV-Infected PWID Receiving a Multi-Level HIV Risk and Stigma Reduction Intervention: Results From a Randomized Controlled Trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 74(2), 166–174. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Go VF, Frangakis C, Minh NL, Latkin C, Ha TV, Mo TT, … Quan VM. (2015). Efficacy of a Multi-level Intervention to Reduce Injecting and Sexual Risk Behaviors among HIV-Infected People Who Inject Drugs in Vietnam: A Four-Arm Randomized Controlled Trial. PLoS One, 10(5), e0125909. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Go VF, Frangakis C, Minh NL, Latkin CA, Ha TV, Mo TT, … Quan VM (2013). Effects of an HIV peer prevention intervention on sexual and injecting risk behaviors among injecting drug users and their risk partners in Thai Nguyen, Vietnam: A randomized controlled trial. Soc Sci Med, 96, 154–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Go VF, Latkin C, Minh NL, Frangakis C, Ha TV, Sripaipan T, … Quan VM (2016). Variations in the role of social support on disclosure among newly diagnosed HIV-infected people who inject drugs in Vietnam. AIDS and Behavior, 20(1), 155–164. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1063-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson NC, & Hussong AM (2013). Drinking to dampen affect variability: findings from a college student sample. J Stud Alcohol Drugs, 74(4), 576–583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha T, Schensul SL, Irving M, Brault MA, Schensul JJ, Prabhughate P, & Vaz M (2018). Depression Among Alcohol Consuming, HIV Positive Men on ART Treatment in India. AIDS and Behavior doi: 10.1007/s10461-018-2339-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendershot CS, Stoner SA, Pantalone DW, & Simoni JM (2009). Alcohol use and antiretroviral adherence: review and meta-analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 52(2), 180–202. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b18b6e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershow RB, Zuskov DS, Vu Tuyet Mai N, Chander G, Hutton HE, Latkin C, … Go VF (2018). “[Drinking is] Like a Rule That You Can’t Break”: Perceived Barriers and Facilitators to Reduce Alcohol Use and Improve Antiretroviral Treatment Adherence among People Living with HIV and Alcohol Use Disorder in Vietnam. Subst Use Misuse, 53(7), 1084–1092. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2017.1392986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM (2007). Predictors of drinking immediacy following daily sadness: an application of survival analysis to experience sampling data. Addict Behav, 32(5), 1054–1065. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.07.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM, Ennett ST, McNeish D, Rothenberg WA, Cole V, Gottfredson NC, & Faris RW (2018). Teen Social Networks and Depressive Symptoms-Substance Use Associations: Developmental and Demographic Variation. J Stud Alcohol Drugs, 79(5), 770–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM, Jones DJ, Stein GL, Baucom DH, & Boeding S (2011). An internalizing pathway to alcohol use and disorder. Psychol Addict Behav, 25(3), 390–404. doi: 10.1037/a0024519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane JC, Elafros MA, Murray SM, Mitchell EMH, Augustinavicius JL, Causevic S, & Baral SD (2019). A scoping review of health-related stigma outcomes for high-burden diseases in low- and middle-income countries. BMC Med, 17(1), 17. doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1250-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, & Folkman S (1987). Transactional theory and research on emotions and coping. European Journal of Personality, 1, 141–169. [Google Scholar]

- Leggett A, Zarit SH, Nguyen NH, Hoang CN, & Nguyen HT (2012). The influence of social factors and health on depressive symptoms and worry: a study of older Vietnamese adults. Aging Ment Health, 16(6), 780–786. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2012.667780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levintow SN, Pence BW, Ha TV, Minh NL, Sripaipan T, Latkin CA, … Go VF (2018). Prevalence and predictors of depressive symptoms among HIV-positive men who inject drugs in Vietnam. PLoS One, 13(1), e0191548. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0191548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima VD, Kerr T, Wood E, Kozai T, Salters KA, Hogg RS, & Montaner JS (2014). The effect of history of injection drug use and alcoholism on HIV disease progression. AIDS Care, 26(1), 123–129. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.804900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln M (2016). Alcohol and drinking cultures in Vietnam: A review. Drug Alcohol Depend, 159, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.10.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Ruan Y, Strauss SM, Yin L, Liu H, Amico KR, … Vermund SH (2016). Alcohol misuse, risky sexual behaviors, and HIV or syphilis infections among Chinese men who have sex with men. Drug Alcohol Depend, 168, 239–246. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.09.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longmire-Avital B, Holder CA, Golub SA, & Parsons JT (2012). Risk factors for drinking among HIV-positive African American adults: the depression-gender interaction. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse, 38(3), 260–266. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2011.653425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunze K, Lioznov D, Cheng DM, Nikitin RV, Coleman SM, Bridden C, … Samet JH (2017). HIV Stigma and Unhealthy Alcohol Use Among People Living with HIV in Russia. AIDS Behav, 21(9), 2609–2617. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-1820-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luu BN, Nguyen TT, & Newman IM (2014). Traditional alcohol production and use in three provinces in Vietnam: an ethnographic exploration of health benefits and risks. BMC Public Health, 14, 731. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno Y, Purcell DW, Dawson-Rose C, Parsons JT, & Team S (2003). Correlates of depressive symptoms among HIV-positive injection drug users: the role of social support. AIDS Care, 15(5), 689–698. doi: 10.1080/09540120310001595177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mugavero M, Ostermann J, Whetten K, Leserman J, Swartz M, Stangl D, & Thielman N (2006). Barriers to antiretroviral adherence: the importance of depression, abuse, and other traumatic events. AIDS Patient Care STDS, 20(6), 418–428. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanni MG, Caruso R, Mitchell AJ, Meggiolaro E, & Grassi L (2015). Depression in HIV infected patients: a review. Curr Psychiatry Rep, 17(1), 530. doi: 10.1007/s11920-014-0530-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palfai TP, Cheng DM, Coleman SM, Bridden C, Krupitsky E, & Samet JH (2014). The influence of depressive symptoms on alcohol use among HIV-infected Russian drinkers. Drug Alcohol Depend, 134, 85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.09.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pence BW, Thielman NM, Whetten K, Ostermann J, Kumar V, & Mugavero MJ (2008). Coping strategies and patterns of alcohol and drug use among HIV-infected patients in the United States Southeast. AIDS Patient Care STDS, 22(11), 869–877. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peretti-Watel P, Spire B, Lert F, Obadia Y, & Group V (2006). Drug use patterns and adherence to treatment among HIV-positive patients: evidence from a large sample of French outpatients (ANRS-EN12-VESPA 2003). Drug Alcohol Depend, 82 Suppl 1, S71–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). A self-report depressive symptoms scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rapier R, McKernan S, & Stauffer CS (2019). An inverse relationship between perceived social support and substance use frequency in socially stigmatized populations. Addict Behav Rep, 10, 100188. doi: 10.1016/j.abrep.2019.100188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salter ML, Go VF, Minh NL, Gregowski A, Ha TV, Rudolph A, … Quan VM (2010). Influence of Perceived Secondary Stigma and Family on the Response to HIV Infection Among Injection Drug Users in Vietnam. AIDS Educ Prev, 22(6), 558–570. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2010.22.6.558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott-Sheldon LAJ, Walstrom P, Carey KB, Johnson BT, Carey MP, & Team MR (2013). Alcohol Use and Sexual Risk Behaviors among Individuals Infected with HIV: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis 2012 to Early 2013. Current HIV/AIDS Reports, 10(4), 314–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seth P, Kidder D, Pals S, Parent J, Mbatia R, Chesang K, … Bachanas P (2014). Psychosocial Functioning and Depressive Symptoms Among HIV-Positive Persons Receiving Care and Treatment in Kenya, Namibia, and Tanzania. Prev Sci, 15(3), 318–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherbourne CD, & Stewart AL (1991). The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med, 32(6), 705–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverberg MJ, Leyden WA, Leibowitz A, Hare CB, Jang HJ, Sterling S, … Satre DD (2018). Factors associated with hazardous alcohol use and motivation to reduce drinking among HIV primary care patients: Baseline findings from the Health & Motivation study. Addict Behav, 84, 110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.03.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor HO, Taylor RJ, Nguyen AW, & Chatters L (2018). Social Isolation, Depression, and Psychological Distress Among Older Adults. J Aging Health, 30(2), 229–246. doi: 10.1177/0898264316673511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesfaw G, Ayano G, Awoke T, Assefa D, Birhanu Z, Miheretie G, & Abebe G (2016). Prevalence and correlates of depression and anxiety among patients with HIV on-follow up at Alert Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Psychiatry, 16(1), 368. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-1037-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thai TT, Jones MK, Harris LM, & Heard RC (2016). Screening value of the Center for epidemiologic studies - depression scale among people living with HIV/AIDS in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam: a validation study. BMC Psychiatry, 16, 145. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0860-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran BX, Nguyen LT, Do CD, Nguyen QL, & Maher RM (2014). Associations between alcohol use disorders and adherence to antiretroviral treatment and quality of life amongst people living with HIV/AIDS. BMC Public Health, 14, 27. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran BX, Nguyen N, Ohinmaa A, Duong AT, Nguyen LT, Van Hoang M, … Veugelers PJ (2013). Prevalence and correlates of alcohol use disorders during antiretroviral treatment in injection-driven HIV epidemics in Vietnam. Drug Alcohol Depend, 127(1–3), 39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vietnam AIDS Response Progress Report 2014: Following up the 2011 Political Declaration on HIV/AIDS. (2014). Retrieved from Hanoi: http://www.aidsdatahub.org/sites/default/files/publication/Vietnam_narrative_report_2014.pdf

- Williams EC, Hahn JA, Saitz R, Bryant K, Lira MC, & Samet JH (2016). Alcohol Use and Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Infection: Current Knowledge, Implications, and Future Directions. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 40(10), 2056–2072. doi: 10.1111/acer.13204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.