Abstract

Most autistic adults struggle with mental health problems, and traditional mental health services generally do not meet their needs. The present study used qualitative methods to identify ways to improve community mental health services for autistic adults for treatment of their co-occurring psychiatric conditions. We conducted semi-structured, open-ended interviews with 22 autistic adults with mental healthcare experience, 44 community mental health clinicians, and 11 community mental health agency leaders in the United States. Participants identified clinician-, client-, and systems-level barriers and facilitators to providing quality mental healthcare to autistic adults. Across all three stakeholder groups, most of the reported barriers involved clinicians’ limited knowledge, lack of experience, poor competence, and low confidence working with autistic adults. All three groups also discussed the disconnect between the community mental health and developmental disabilities systems, which can result in autistic adults being turned away from services when they contact the mental health division and disclose their autism diagnosis during the intake process. Further efforts are needed to train clinicians to work more effectively with autistic adults and to increase coordination between the mental health and developmental disabilities systems.

Keywords: adults, autism spectrum disorder, community mental health, training, qualitative methods

Lay Abstract

Most autistic adults struggle with mental health problems, such as anxiety and depression. However, they often have trouble finding effective mental health treatment in their community. The goal of this study was to identify ways to improve community mental health services for autistic adults. We interviewed 22 autistic adults with mental healthcare experience, 44 community mental health clinicians (outpatient therapists, case managers, and intake coordinators), and 11 community mental health agency leaders in the United States. Our participants identified a variety of barriers to providing quality mental healthcare to autistic adults. Across all three groups, most of the reported barriers involved clinicians’ limited knowledge, lack of experience, poor competence, and low confidence working with autistic adults. All three groups also discussed the disconnect between the community mental health and developmental disabilities systems and the need to improve communication between these two systems. Further efforts are needed to train clinicians and provide follow-up consultation to work more effectively with autistic adults. A common suggestion from all three groups was to include autistic adults in creating and delivering the clinician training. The autistic participants provided concrete recommendations for clinicians, such as consider sensory issues, slow the pace, incorporate special interests, use direct language, and set clear expectations. Our findings also highlight a need for community education about co-occurring psychiatric conditions with autism and available treatments, in order to increase awareness about treatment options.

More than half of autistic adults struggle with mental health problems, most commonly anxiety and depression (Buck et al., 2014; Croen et al., 2015; Gillberg, Helles, Billstedt, & Gillberg, 2016; Hofvander et al., 2009). These co-occurring conditions can cause substantial impairment and increase the risk of poor outcomes in areas of adaptive functioning, employment, and quality of life (Farley et al., 2009; Gillberg et al., 2016; Joshi et al., 2010). Despite their high prevalence and associated impairment, mental health difficulties often are left untreated in autistic adults (Anderson & Butt, 2018; Roux, Shattuck, Rast, Rava, & Anderson, 2015; Shattuck, Wagner, Narendorf, Sterzing, & Hensley, 2011; Tint & Weiss, 2018). A growing body of research suggests that modified cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) reduces anxiety and depression in autistic adults (Spain, Sin, Chalder, Murphy, & Happé, 2015). However, few community-based clinicians are equipped to deliver it.

The current study focuses on community mental health centers, which serve millions of children and adults with a wide range of psychiatric conditions in the United States (Rosenbaum et al., 2018). Community mental health providers often serve clinically complex clients, meaning individuals who present with serious mental illness (e.g., psychosis), chronic mental health problems, and multiple co-occurring conditions. Community mental health centers are publicly funded, meaning they are accessible to people without private insurance or without the financial means to pay out of pocket. This financial consideration is particularly important for autistic adults and their families, given that many autistic adults are under- or unemployed (Farley et al., 2018; Roux, Rast, Anderson, & Shattuck, 2017) and that many providers with expertise in autism in adulthood are private pay only (Anderson & Butt, 2018).

Community mental health centers play an important role in treating school-age autistic youth with co-occurring psychiatric conditions (e.g., Brookman-Frazee, Drahota, Stadnick, & Palinkas, 2012; Mandell, Walrath, Manteuffel, Sgro, & Pinto-Martin, 2005), and there have been recent efforts to improve these services (e.g., Brookman-Frazee, Drahota, & Stadnick, 2012; Wood, McLeod, Klebanoff, & Brookman-Frazee, 2015). However, little is known about community mental health services for autistic adults. We conducted this study to better understand the factors associated with access to and quality of community mental health services for this population. Given our interest in improving community mental health services, this study is focused on adults who could benefit from outpatient psychotherapy for co-occurring psychiatric conditions, not on adults who primarily need supports related to severe cognitive or functional impairments.

Previous studies found that adult medical providers (Zerbo, Massolo, Qian, & Croen, 2015) and community mental health clinicians serving youth (Brookman-Frazee et al., 2012b) report limited training, knowledge, and comfort in caring for autistic individuals. To our knowledge, no published studies have interviewed community mental health leaders and clinicians serving adults about their experiences and needs related to treating autistic adults, nor have prior studies directly asked autistic adults about their preferences related to community mental health care and community mental health provider practices in the United States. In the UK, Camm-Crosbie, Bradley, Shaw, Baron-Cohen, and Cassidy (2019) explored autistic adults’ experiences of mental health services and support using an online survey. Their participants expressed a strong desire for individually tailored treatment. Similarly, Crane, Adams, Harper, Welch, and Pellicano (2019a) partnered with young adults on the autism spectrum in the UK to learn about their experiences with mental health problems and related services or supports. Their interview participants noted that improvements to mental health services are needed because current services are not tailored to autistic individuals.

To address the dearth of research characterizing community mental health services for autistic adults in the United States, we used qualitative methods to identify initial care improvement targets for this important community service system. We interviewed three groups of stakeholders: autistic adults, community mental health clinicians, and community mental health agency leaders. We included multiple perspectives to 1) identify barriers and facilitators to providing quality mental healthcare to autistic adults, and 2) explore convergent and divergent stakeholder perspectives. Established implementation science frameworks (e.g., Proctor et al., 2009) informed our interview questions, which were designed to capture clinician, client, and system-level barriers.

Methods

Procedures

All procedures were approved by the University of Pennsylvania’s Institutional Review Board. All participants provided consent prior to participating. At their own discretion (based on personal preference and scheduling logistics), clinicians and agency leaders participated in either an individual interview or a focus group conducted at their agency. We conducted individual interviews with each autistic participant, due to the sensitive nature of the questions. Autistic adults were invited to include family members if desired. Interviews with autistic adults took place in a private room at a university-based research center or over the phone, depending on the participant’s preference. All interviews were completed by a master’s- or doctoral-level clinical researcher (SC, BM). The interviewers wrote field notes during and immediately after each interview, and they met together after each interview to debrief about their experience and impressions. Interviews lasted approximately 30–45 minutes and were audio recorded. All participants also completed a brief demographic questionnaire. Each participant was compensated $25.

Interview questions were open-ended and included follow-up probes to tailor the interview to the participants’ responses. Questions followed a systematic, semi-structured interview guide to ensure uniform inclusion and sequencing of topics across interviews. The questions were based on a similar interview guide used to develop a mental health intervention protocol for autistic children served in community mental health centers (Brookman-Frazee et al., 2012b). Three interview guides, tailored to each of the stakeholder groups, were developed in consultation with qualitative methods experts (RB, CC, CN), including one with expertise interviewing autistic adults (see Appendix for interview questions). The interview guide for autistic adults included questions about mental health experiences as adults, perceptions of community mental health centers, and recommendations for improving mental healthcare for autistic adults. We offered the autistic participants a copy of the interview questions in advance and told them that we would also ask follow-up questions. The interview guide for clinicians included questions that probed knowledge and experiences related to autistic adults, as well as resources and strategies that could potentially increase their comfort in working with autistic adults. For agency leaders, the interview guide included questions to assess their knowledge of autism in adulthood, their views on their center’s experience and perceived needs related to providing mental health services to autistic adults, and their recommendations for a clinician training program. During each interview, the interviewer shared a verbal summary of what she heard the participants say in response to each of the interview guide questions, asked participants if she had correctly interpreted their answers, and sought clarification as needed, in an effort to accurately capture their intended meanings.

Participants

Autistic participants

We recruited autistic adults through the Center for Autism Research’s online research registry, the University of Pennsylvania’s Adult Autism Spectrum Program, and local support groups for autistic adults. Eligibility criteria for the autistic participants included being at least 18 years of age, having the expressive language abilities necessary to complete the interview in English (as confirmed by a brief phone screen with the potential participant), and reporting a formal diagnosis from a qualified professional of autistic disorder, Asperger’s, pervasive developmental disorder-not otherwise specified, or autism spectrum disorder. Twenty-seven autistic adults or their parents contacted the study team to express interest in participating. After answering several screening questions over the phone, 5 individuals were found to not be eligible to participate (1 was younger than 18 years old, 2 were described as nonverbal by their parents, and 2 did not have a formal autism diagnosis). The autistic participants (n = 22) averaged 34.4 years of age (SD = 12.9 years). Most participants identified as male (77.3%); 22.7% identified as female. Participants identified as white (81.2%), Asian (9.1%), black (4.5%), more than one race (4.5%), and Hispanic/Latino (4.5%). Most (59.1%) reported that they received their formal autism diagnosis after age 18. Half had a high school degree, 4.5% had a vocational degree, 27.3% had a college degree, and 18.2% had a graduate school degree as their highest level of education. Participants also varied in their employment status at the time of the interview: 27.3% were not employed, 40.9% had a part-time job, and 31.8% had a full-time job. Most participants lived either with their parents (40.9%) or alone (31.8%). All autistic participants completed an individual interview with a member of the research team (16 in person; 6 over the phone). Three elected to have a parent present during the interview; for these interviews, questions were still primarily directed toward the autistic adult, with parents elaborating on responses if the autistic adult desired. Of the 22 participants, 21 had received mental health services during adulthood.

Clinician participants

Clinicians were recruited through an email message sent from two organizations that collectively represent more than 70 independent community mental health agencies in Southeastern Pennsylvania. Practitioners who solely provide medication management services were excluded, given the study’s focus on mental health clinicians who provide outpatient psychotherapy. The clinician participants included outpatient therapists, case managers, and intake coordinators who work with adults at generalist centers (i.e., not autism specialty centers). Forty-five clinicians expressed interest in participating in the study; one clinician was not scheduled for an interview because she reported only working with children, not adults. The final sample size of 44 clinicians ensured representation from the six community mental health centers where we interviewed agency leaders (see below for more details). Participating clinicians were predominantly female (93.2%) and were an average of 39.1 years old (SD = 13.6 years). They identified as white (79.5%), black (18.2%), Hispanic/Latino (18.2%), and more than one race (2.3%). Most held master’s degrees (75.0%); 9.1% held a doctorate in psychology, 13.6% had a college degree, and 2.3% had a medical degree. Clinicians reported an average of 10.5 years of clinical experience (SD =11.3 years). Participating clinicians shared similar demographics with clinicians in previous research with Philadelphia community mental health centers (e.g., Beidas, Edmunds, Marcus, & Kendall, 2012). Thirty-six of the 44 clinicians participated in a group interview (9 separate focus groups). The remaining 8 clinicians completed an individual interview.

Agency leader participants

Agency leaders (n = 11) included clinical and executive directors of various service lines from six community mental health centers in Philadelphia. Our team presented about the study at two agency leader meetings, held by a trade organization that represents more than 70 independent community mental health centers in Southeastern Pennsylvania. Agency leaders who expressed interest in participating were contacted directly about the interview. No participating agencies offered autism-specific mental health programming at the time of the study, but all expressed interest in developing these services. The agency leaders were predominantly white (90.9%), and 9.1% were black. Six were males (54.5%). They were an average of 48.4 years old (SD = 10.3 years) and had an average of 4.3 years (SD = 3.9 years) experience in their current leadership roles. All held master’s degrees or higher. Six participated in individual interviews, and the remaining 5 participated in one of two group interviews.

Analysis

All interviews were professionally transcribed and imported into NVivo 11 for data management and coding. We conducted a thematic analysis because we were interested in identifying themes from the data (Braun & Clarke, 2006). We followed the six phases of thematic analysis, including familiarizing ourselves with the data, generating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes, and producing a scholarly report (Braun & Clarke, 2006). We used an inductive approach, at a semantic level, to ground our findings in statements directly from the participants, as opposed to a theoretical approach where themes are selected based on the researchers’ theories or a literature review (Bradley, Curry, & Devers, 2007). Through a close reading of six randomly selected transcripts (two transcripts per stakeholder group), a clinical psychologist with expertise in autism (BM) and a clinical research coordinator with experience providing community mental health services (SC) developed a set of codes that were applied to the data. A random subset of all transcripts (20%) was coded by the same two investigators, and inter-rater reliability was found to be excellent (ĸ = .97 for autistic participants, ĸ = .91 for clinician participants, ĸ = .97 for agency leader participants). The coding team collaboratively identified themes using a subjective heuristic for determining significance. A significant theme needed to be expressed by multiple participants, to hold valence for the participants, and to be related to mental healthcare for autistic adults. We used the field notes from each interview to triangulate the findings. The first author then produced memos that included example quotations and commentary regarding preliminary themes. The larger multidisciplinary research team reviewed the codes, discussed preliminary findings and the memos on multiple occasions, and finalized themes through an iterative process. During these team meetings, we discussed our clinical and personal roles and how these could affect our interpretation of the findings. We also distributed a report of the main study findings to all study participants for their input.

Results

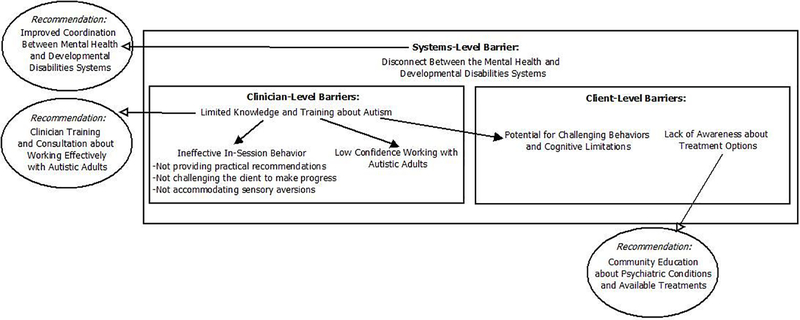

All three stakeholder groups provided information about key barriers and facilitators to quality mental healthcare for autistic adults with co-occurring psychiatric conditions. There were no notable differences in themes between the interviews and focus groups. Participant numbers are used below to identify direct quotations, per the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ; Tong, Sainsbury, & Craig, 2007). While we begin this section with challenges from the perspectives of autistic adults, clinicians, and agency leaders, we conclude with a series of practical recommendations offered by the autistic participants to transform therapy to better meet their needs. Figure 1 summarizes the main themes and shows the relationships between themes.

Figure 1.

Barriers to quality mental healthcare for autistic adults with co-occurring psychiatric conditions and associated recommendations.

Barriers

Barriers to mental healthcare for autistic adults broadly fell into three categories: clinician-, client-, and systems-level barriers.

Clinician-level barriers

Of the 22 autistic adults interviewed, 20 described having negative psychotherapy experiences during adulthood. The most common explanations for what made these experiences negative related to the clinician, particularly that the clinician did not understand autism. For example, according to one autistic adult (P49): “I can’t even find therapists who know very much about autism spectrum disorders. So I have to continually be trying to tell them that my needs are not the same and it is a real challenge to sometimes work with these folks [therapists].” Another frequently cited complaint was that the clinician did not provide practical recommendations, but rather spent the session processing the adult’s emotions or talking about the adult’s childhood experiences. As one autistic adult (P20) described about his previous therapists, “They’d ask me questions, how you feel about this, how you feel about that, and the harder I thought about it, the more I couldn’t figure out what I was feeling like… That was kind of useless.” Many participants noted that the clinician did not challenge the autistic adult to make progress, which they perceived as the clinician not believing they could make meaningful improvements in their overall functioning or quality of life due to their autism diagnosis. Lastly, participants described negative experiences when the clinician did not accommodate the autistic adult’s sensory aversions. Specifically, they reported feeling distracted and/or distressed during therapy sessions due to stimuli such as the smell of perfume or bright overhead lighting, along with dirty conditions (e.g., dust on computer wires) and uncomfortable seating (e.g., old, sagging chair).

Clinician participants reported similar challenges, stating that their limited knowledge about autism was a major barrier to treating adults on the spectrum. When asked about previous autism training, 43 of the 44 clinicians could not recall learning anything about autistic adults in their educational programs. The one exception was a clinician who completed a behaviorally-oriented master’s program that included training in applied behavioral analysis. One other clinician reported considerable experience working with autistic adults in their current role. About half (n = 21) reported no professional experience working with autistic adults (either with an official or suspected diagnosis). Eleven clinicians had experience working with only one autistic adult; the remaining 11 said they had experience working with between 2–5 autistic adults. The agency leaders agreed that the clinicians at their centers lacked formal training and clinical experience treating autistic adults.

According to the clinicians and agency leaders, limited knowledge about autism leads to poor competence and low confidence working with this population. As one clinician (P29) stated, “I’ve worked with a lot of diverse populations of all ages, but this is the one area that I would not feel competent to work with.” Another clinician (P13) noted, “I probably wouldn’t know where to start in terms of psychotherapy. I would need more training into the mind of an autistic patient.” Only two clinicians described themselves during the interview as “very comfortable” working with adults on the spectrum; 16 were “fairly comfortable” and 26 were “not comfortable.” The two quotations below highlight the interplay among lack of training, limited knowledge, and low confidence.

Clinician (P68): “I don’t think I would feel that comfortable [working with autistic adults] because I don’t really have the skills. I don’t see myself helping that person because of my training. It would be a disservice to that client.”

Agency leader (P5): “I think people are afraid to treat people with autism because they don’t know what to do. I think if clients have anxiety or depression or schizophrenia, then there’s a better road map and they feel better trained to do that. They’re not trained to deal with people with autism or to manage that. So I think that people are scared to do it.”

Client-level barriers

Only the clinicians and agency leaders identified client-related barriers. As noted above, clinicians in this sample had limited contact with autistic adults, so their perceived barriers may not reflect direct experience in a clinical setting, but rather reflect their anticipated challenges if they were to work with autistic adult clients. Clinician participants expressed concern about autistic adults exhibiting challenging behaviors during session. For example, when asked about challenges to effective mental health treatment, one clinician (P56) answered, “Well, the escalating aggression. First there’s the pacing or the rocking, maybe the raising of the voice. And now there’s a crowd of people trying to intervene. It can happen pretty quickly.” Clinicians also noted that the client’s cognitive limitations can interfere with traditional therapy: “I think it’s challenging trying to do insight-oriented work or focusing in on cognitions when people have a difficult time understanding” (P18). Given this concern, several clinicians questioned whether CBT would be appropriate for autistic adults.

According to agency leaders, one main reason why more autistic adults with co-occurring psychiatric conditions are not seeking community mental health services is a lack of awareness about available treatment. Specifically, agency leaders commented that many autistic adults and their families do not think to call a community mental health center – this option is “not on their radars” (P5). This issue may relate to autistic adults not knowing about community mental health centers or not recognizing signs of psychiatric conditions in themselves.

Systems-level barriers

All three groups discussed the problematic disconnect between the mental health and developmental disabilities systems, which can result in autistic adults being turned away from mental health services. Several autistic adults remembered hearing “oh, we don’t treat autism” when they called a therapy provider for depression or anxiety. They expressed frustration that they were not accepted as clients by mental health providers, given their autism diagnosis. Clinicians and agency leaders agreed that there is not a strong system in place for autistic adults with mental healthcare needs. These adults often are placed in the developmental disabilities system and not referred to mental health services. As one agency leader (P26) from the mental health division stated:

“I think if a person came into our clinics, an adult with autism who may be having some adjustment problems or depressed mood or perhaps something more severe than that, there’d be an inclination for people to direct them to the Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities division and not see that it’s something that we could also accommodate. And that could be because of unfamiliarity. That could be because of fear that you wouldn’t be able to know what to do. And so – well, let me at least send it over there. At least I’m doing a job, directing somebody to somebody who knows something.”

Facilitators

The three stakeholder groups prioritized ways to improve community mental health services for autistic adults with co-occurring psychiatric conditions. Most responses focused on clinicians’ training needs. The autistic adults provided seven main recommendations for clinicians, described below with an example quotation for each.

According to the autistic adults, clinicians should use clear and direct language. This consideration includes avoiding or explaining metaphors, using concrete terms, speaking concisely, and periodically checking in to make sure the clinician and client have a shared understanding about key concepts. “One of my favorite sayings is say what you mean and mean what you say, especially with working with people on the spectrum because we’re not going to get the nuances. So if you don’t say it, I didn’t hear it” (P45). On a similar note, the autistic participants would like clinicians to provide structure and predictability. Examples of how to do this include posting a written agenda for the session time, following a similar structure for each session, and keeping a regular appointment time each week. Perhaps most importantly, clinicians should take adequate time before initiating treatment to explain what the client can expect: “Set the expectations about what happens in therapy. You should just make those expectations clear from the beginning” (P51). Another recommendation related to the clinician’s communication is be comfortable with silence and slow pacing, given that some people on the spectrum may need additional time to process verbal information and formulate a response. As one autistic participant (P16) explained:

“It seems like for neurotypical people silence is really uncomfortable and space is really uncomfortable. It’s something that people with autism need more of. So just allowing that, whatever it’s for - because you need to process the sensory information or you need to process the messages that you’re getting. Yeah. Take it slow. Take it slow.”

The autistic participants encouraged clinicians to individualize treatment. Specifically, many participants expressed concern that clinicians have a set idea about what autism means and would not take the time to figure out the individual client’s unique profile of strengths, weaknesses, and interests. As one participant (P54) said:

“Just know who you’re talking to. Know that a lot of people with autism are very smart and a lot of them have great skills and a lot of them have great potential, and just figure out how can you specifically tailor to this specific person’s needs and interests. And how can you make it relatable and memorable. And what’s relatable to him may not be relatable to her and vice versa.”

When assessing an individual client’s areas of strength and need, clinicians should consider sensory issues and do their best to make therapy a comfortable environment for the autistic participant. Possible accommodations could include limiting the amount of time the autistic client spends in the crowded waiting room or dimming the lights in the clinician’s office. One participant (P27) described his desire to lead clinicians through a simulation exercise so they could understand the stressful experience of sensory overload:

“I want to take a whole bunch of therapists in the same room, have them close their eyes, and imagine being bombarded by sensations that they cannot filter out. Just imagine the stress. You’re trying to concentrate on something and somebody’s whistling or knocking or doing something like that.”

As for particular treatment strategies, the autistic participants recommended that clinicians use practical, present-focused therapeutic approaches. They want clinicians to be more than just a listening ear and provide information, with concrete examples, about the best ways to handle certain situations in their current lives:

“I need, as someone who is in their mid-thirties, to get my life together. So I really don’t want to go through neurotic stuff from my childhood and things like that. If that’s important for what’s happening right now, then yes, but otherwise I don’t want to sit around talking about that. I want you to talk to me about how I can get a job, how to talk to people, those social skills” (P16).

Another recommendation for treatment strategies comes from the autistic participants urging clinicians to focus on treating the co-occurring conditions, not on changing core autistic traits. That is, when an autistic adult presents for mental health treatment, the treatment target should be the primary mental health concern. Although certain autism characteristics may affect the treatment plan, the clinician should not lose sight of the presenting concern, which is likely causing the most distress and impairment currently in the individual’s life. One participant (P60) explained that this factor had a large effect on his overall satisfaction with therapy: “My therapist is really principally just trying to treat the depression and the anxiety. He’s trying to treat what he can because autism, you can’t really treat it.”

Clinicians and agency leaders report that they want training to include an overview of autism (“the basics”), education about how to screen for or assess autism in adults, details about effective mental health treatments for autistic adults, and information about available community resources for autistic adults. Many clinicians and agency leaders noted that this training would need to be more than a one-time workshop, but instead include follow-up supervision/ consultation with an expert.

A common recommendation from all three groups was to include autistic adults in creating and delivering the training. Several autistic participants spontaneously volunteered to help lead clinicians through a training activity to simulate sensory overload. One clinician (P30) stated, “I think it would be helpful to hear from the perspective of adults with autism what they hear when a clinician speaks to them in certain ways, almost like a translation.” All three groups also noted that the training should reach beyond outpatient therapists, because front desk staff, supervisors, case managers, and psychiatrists also need improved knowledge about autistic adults to improve community mental health services broadly for this population.

In addition to the training needs described above, agency leaders noted a few other needs, mostly related to more funding and resources, to improve sustainability of services. Agency leaders also specified a community education need (“marketing and advertising”). That is, in order for more autistic adults to receive quality mental health services, they need to be aware of co-occurring psychiatric conditions and available treatments at community mental health centers. Agency leaders made clear that the advertising of services goes hand-in-hand with clinician training: “We certainly need information to the community that the services are available. But that implies that before one would make such a promotion that one has trained clinicians to address the issue. Otherwise, it’s gross misrepresentation” (P26).

Discussion

This qualitative study is among the first to examine ways to build the capacity of community mental health centers to address the mental health needs of autistic adults. Our current mental health system fails many autistic adults (Roux et al., 2015), but previous research has not investigated barriers and facilitators to address this problem in the United States. This paper advances the literature on mental health services for autistic adults by describing difficulties and possible solutions at the clinician, client, and system level. These three levels are consistent with prior work on factors affecting autistic adults’ experiences with medical care (Nicolaidis et al., 2015).

Most of the reported barriers in this sample relate to the clinician, and include clinicians’ limited knowledge, lack of experience, poor competence, and low confidence working with autistic adults. Interestingly, the autistic participants reported a mix of autism-specific factors (e.g., the clinician not understanding autism) and more general factors (e.g., the clinician not providing practical recommendations). The perception from autistic adults that mental health providers lack knowledge about autism is consistent with previous research on autistic adults’ experiences with medical and mental health providers (Camm-Crosbie et al., 2019; Crane et al., 2019a; Lipinski, Blanke, Suenkel, & Dziobek, 2018; Nicolaidis et al., 2015; Raymaker et al., 2017; Tint & Weiss, 2018). In a recent study of 245 autistic adults in Germany, outpatient therapists’ low level of expertise with autism was the main reason for the autistic adults being declined by therapists and a contributing factor to overall treatment dissatisfaction (Lipinski et al., 2018).

Similarly, the clinician and agency leader participants reported that clinicians lack training, knowledge, and comfort in serving autistic adults, which is consistent with findings from adult medical providers (Zerbo et al., 2015) and community mental health clinicians serving autistic youth (Brookman-Frazee et al., 2012b). Given the high rates of anxiety and depression in autistic adults (Croen et al., 2015), it is surprising how few community mental health clinicians have worked with this population. Although treating anxiety and depression is routine for community mental health clinicians, when these common psychiatric conditions present in the context of autism, clinicians feel unprepared.

These themes highlight the need for clinician training, both at the pre-service level (i.e., in graduate programs through coursework and practicum placements) and in continuing education. All three stakeholder groups provided practical recommendations for designing and implementing a clinician training program, taking into account the content and format of the training, along with whom to include in the training. Although clinician training is an important step toward improving community mental health services for autistic adults, training alone is likely insufficient to produce meaningful change in clinician behavior (Beidas et al., 2012), and future research should examine other implementation strategies. In addition, it is notable that the autistic adults’ stated preferences for therapy sessions fit nicely with CBT, which is a practical, present-focused, structured therapeutic approach with a growing evidence base for use in this population (Spain et al., 2015). The autistic participants’ recommendations to consider sensory issues, slow the pace, incorporate special interests, use direct language, and set clear expectations align with published guidelines for modifying CBT for autistic adults (Kerns, Roux, Connell, & Shattuck, 2016; White, Conner, & Maddox, 2017; White et al., 2018).

Only the clinicians and agency leaders reported client-related barriers. Notably, some of these identified barriers reflect clinicians’ misperceptions about autistic adults. That is, several clinicians incorrectly assumed that all autistic adults have problems with aggression and other challenging behaviors or that autistic adults could not engage in talk therapy due to cognitive limitations. Correcting these misperceptions should be a goal of any clinician training program about autism. Although the autistic participants did not explicitly name client-level barriers, their recommendations for clinicians are closely related to previously reported client-level factors affecting autistic adults’ healthcare experiences (e.g., sensory sensitivities, slow processing speed; Nicolaidis et al., 2015).

At the system level, a major barrier is the disconnect between the developmental disabilities and mental health systems. All three stakeholder groups described the problems that occur because the developmental disabilities and mental health systems have very little integration. These problems begin as early as when an autistic adult decides to seek help for a mental health problem, but is turned away due to his or her autism diagnosis and instead referred to the developmental disabilities system. Although developmental disabilities services may be helpful for a range of concerns, they typically do not focus on mental health conditions. Thus, when an autistic adult contacts a developmental disabilities clinic and expresses a desire for mental health treatment, he or she may be referred back to the mental health division. This phenomenon of autistic adults being “punted” between the developmental disabilities and mental health systems in the United States has been described in previous work (Maddox & Gaus, 2018), and parents of young adults on the spectrum find the task of navigating different service systems intimidating and time-consuming (Anderson & Butt, 2018). The lack of coordinated mental health services across systems of care for autistic adults has been documented in the UK as well (Camm-Crosbie et al., 2019; Crane, Davidson, Prosser, & Pellicano, 2019b). It is critical that these different systems improve communication to reduce the confusion and frustration that occurs for autistic adults seeking mental healthcare. Future work could examine the best way to increase coordination between these two systems.

Several study limitations deserve mention. First, we did not randomly select agencies we approached for this study, and the findings may not generalize to other agencies or clinicians, particularly those outside a publicly funded system. However, as with most qualitative studies, we prioritized in-depth understanding over generalizability. In addition, participating clinicians shared similar demographics with clinicians in previous research with Philadelphia community mental health centers (e.g., Beidas et al., 2012), which increases our confidence that they are representative of clinicians in this area. Similarly, the autistic sample may not be representative of the broader population of autistic adults, particularly autistic adults without mental healthcare experience, since most of our sample accessed mental health services during adulthood. All participants self-selected to complete an interview, and they may differ in important ways from people who did not elect to participate. The autistic participants all had the verbal abilities to complete an interview, which does not reflect the abilities of all autistic adults. However, we focused on this subset of individuals on the spectrum because they have the verbal abilities to engage in outpatient psychotherapy in a community mental health setting. We recognize that community mental health centers may not be an appropriate treatment option for all autistic adults with co-occurring psychiatric conditions. We also note that our sample differs from the broader population of autistic adults in terms of educational attainment, with higher than expected rates of 4-year college and graduate school degrees (Shattuck et al., 2012), which likely affects the generalizability of our findings. More than half of the autistic participants reported that they received their autism diagnosis after age 18, which is likely a higher proportion than exists in the autistic adult population and which may reflect a different life experience than an autistic adult diagnosed in childhood. In addition, the study did not include a formal assessment of autism or co-occurring psychiatric conditions. Finally, our study was limited to participants in a Northeastern urban setting; results may not transfer to other geographical areas, particularly outside the United States, although recent research with autistic adults in the UK revealed similar themes about mental healthcare experiences (Camm-Crosbie et al., 2019; Crane et al., 2019a).

Despite these limitations, this study has important implications. Findings will be used to increase autistic adults’ access to mental health services that have the capacity to address their co-occurring psychiatric conditions. Future efforts could focus specifically on training clinicians to work more effectively with autistic adults and increasing coordination between the developmental disabilities and mental health systems. It is encouraging that all three stakeholder groups included in this study agreed on these priorities. Future research also could use quantitative methods to examine patterns of mental health service access and quality of care in this population, in order to identify how to optimize organization of mental health services (e.g., which types of organizations and providers should be targeted in improvement efforts). Moving forward, it will be important to continue to gather detailed information from stakeholders, which is critical for tailoring interventions for delivery in community settings and facilitating intervention uptake among practitioners working with autistic individuals (Wood et al., 2015). The ultimate goal of this work is to improve community mental health services and quality of life for adults on the spectrum.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to our community partners and the study participants. Portions of these findings were presented at the 2018 International Society for Autism Research Annual Meeting and the 2019 Gatlinburg Conference on Research and Theory in Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. This study was funded by the NIMH F32MH111166 (PI: Maddox) and FAR Fund (PI: Maddox).

Appendix

Interview Guide for Autistic Adults

Thank you for agreeing to talk with me today. As I’ve mentioned, we want to help adults on the autism spectrum get better community treatment for mental health problems, such as depression and anxiety. Today, I want to learn what you think is needed to help adults on the autism spectrum in this way. Your input is crucial – you are the expert about this important topic. I’m looking forward to hearing about your experiences. Please let me know if you have any questions for me along the way.

Tell me what a typical day is like for you.

- Can you tell me about a difficult time you’ve had? [Note to interviewer: Pay attention to the language used by the participant and use their own words to describe emotions (e.g., anxious, stressed, sad).]

- Follow-up: What did you do to help yourself feel better? Where did you go for help? How did you find this place/person?

- If participant did not get help: Can you tell me about a difficult time when you went to someone for help?

- If participant has never gotten help for mental health problems: Have you ever wanted to get help for these problems? If so, what stopped you?

- Tell me about your experience getting help from XX.

- What was it like to get help at that place?

- How did the people there treat you?

- What was good about this experience? What things made you feel better?

- What was bad about this experience? What could have made it better? Was there anything you wish people had done for you?

- Did you think about getting help from anywhere else?

What made it easier for you to get help?

- What made it harder for you to get help?

- Follow-up: Was there any help you needed, but could not get?

Tell me what comes to your mind when you think of a community mental health center.

- Let’s think about a person helping you when you’re going through a hard time. What would you like them to know about working with you?

- Follow-up: What could they do to help you have a good experience?

- Follow-up: What are things you want to make sure they don’t do or say?

Have you had other difficult times that you would like to tell me about?

Tell me about any other places where you’ve gone for help.

What do you enjoying doing in your free time?

Thank you for sharing your experiences with me today. This information is incredibly helpful. Is there anything else you would like to add before we end the interview?

Interview Guide for Clinicians

Thank you for agreeing to talk with me today. As I’ve mentioned, we want to improve community mental health services for adults with autism and co-occurring psychiatric disorders. Today, I want to learn about your experiences working with adults with autism. Your input is crucial – you are the expert about this important topic. I’m looking forward to hearing about your experiences. Please let me know if you have any questions for me along the way.

- Tell me about your current role working here. What is your job title? What are your responsibilities?

- Prompts: What’s your typical caseload?

- What types of clients do you typically see?

- Imagine you are talking with your friends at dinner and someone asks you about adults with autism. How would you describe adults with autism, in as much detail as you can?

- Prompts: How do they behave?

- How do they interact in social situations?

- How do they talk?

- What types of problems do they commonly face?

- Tell me about your experiences working with adults with autism.

- Follow-up: Approximately how many adults with autism have you treated as a clinician here?

- What challenges did they face?

- How did these clients get to you (i.e., referral source)?

- Probe about experiences working other places, if applicable.

In your experience, what strategies work well when treating adults with autism for cooccurring psychiatric disorders?

- What challenges have you faced working with adults with autism?

- Prompts: Challenges related to the client?

- Challenges related to your training?

- Challenges related to broader factors at the organization or systems level?

- Tell me about your education and training experiences related to working with adults with autism.

- Prompts: In school? In-service trainings? CE workshops? Supervision?

- Follow-up: How comfortable do you feel working with adults with autism?

Imagine someone is designing a training program for clinicians working with adults with autism. What would be the important elements of that training program?

Thank you for sharing your perspectives with me today. This information is incredibly helpful. Is there anything else you would like to add before we wrap up?

Interview Guide for Agency Leaders

Thank you for agreeing to talk with me today. As I’ve mentioned, we want to improve community mental health services for adults with autism and co-occurring psychiatric disorders. Today, I want to understand some of the challenges your center may face in meeting the needs of adults with autism. Your input is crucial – you are the expert about this setting. I’m looking forward to learning from you. Please let me know if you have any questions for me along the way.

- Imagine you are talking with your friends at dinner and someone asks you about adults with autism. How would you describe adults with autism, in as much detail as you can?

- Prompts: How do they behave?

- How do they interact in social situations?

- How do they talk?

- What types of problems do they commonly face?

Tell me about your center’s experience with providing mental health services to adults with autism.

Many adults with autism and co-occurring psychiatric disorders are not receiving effective mental health treatment. What do you think makes it difficult for these adults to get quality community mental health services?

Tell me about what it would take to increase the number of adults with autism accessing mental health services at your center.

What would your center need to better meet the mental health needs of this population?

If a training program were developed for your clinicians to improve mental health services for adults with autism, what should that training look like? What are the important elements?

What supports do you need in your role to help more adults with autism get effective community mental health services?

Thank you for sharing your perspectives with me today. This information is incredibly helpful. Is there anything else you would like to add before we wrap up?

References

- Anderson C, & Butt C (2018). Young adults on the autism spectrum: The struggle for appropriate services. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48, 3912–3925. doi: 10.1007/s10803-018-3673-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beidas RS, Edmunds JM, Marcus SC, & Kendall PC (2012). Training and consultation to promote implementation of an empirically supported treatment: A randomized trial. Psychiatric Services, 63, 660–665. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley EH, Curry LA, & Devers KJ (2007). Qualitative data analysis for health services research: Developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Services Research, 42, 1758–1772. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, & Clarke V (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brookman-Frazee LI, Drahota A, & Stadnick N (2012a). Training community mental health therapists to deliver a package of evidence-based practice strategies for school-age children with autism spectrum disorders: A pilot study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42, 1651–1661. doi: 10.1007/s10803-011-1406-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookman-Frazee L, Drahota A, Stadnick N, & Palinkas LA (2012b). Therapist perspectives on community mental health services for children with autism spectrum disorders. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 39, 365–373. doi: 10.1007/s10488-011-0355-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck TR, Viskochil J, Farley M, Coon H, McMahon WM, Morgan J, & Bilder DA (2014). Psychiatric comorbidity and medication use in adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44, 3063–3071. doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2170-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camm-Crosbie L, Bradley L, Shaw R, Baron-Cohen S, & Cassidy S (2019). ‘People like me don’t get support’: Autistic adults’ experiences of support and treatment for mental health difficulties, self-injury and suicidality. Autism, 23, 1431–1441. doi: 10.1177/1362361318816053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane L, Adams F, Harper G, Welch J, & Pellicano E (2019a). ‘Something needs to change’: Mental health experiences of young autistic adults in England. Autism, 23, 477–493. doi: 10.1177/1362361318757048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane L, Davidson I, Prosser R, & Pellicano E (2019b). Understanding psychiatrists’ knowledge, attitudes and experiences in identifying and supporting their patients on the autism spectrum: Online survey. BJPsych Open, 5, 1–8. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2019.12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croen LA, Zerbo O, Qian Y, Massolo ML, Rich S, Sidney S, & Kripke C (2015). The health status of adults on the autism spectrum. Autism, 19, 814–823. doi: 10.1177/1362361315577517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farley M, Cottle KJ, Bilder D, Viskochil J, Coon H, & McMahon W (2018). Mid-life social outcomes for a population-based sample of adults with ASD. Autism Research, 11, 142–152. doi: 10.1002/aur.1897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farley MA, McMahon WM, Fombonne E, Jenson WR, Miller J, Gardner M, … Coon H (2009). Twenty-year outcome for individuals with autism and average or near-average cognitive abilities. Autism Research, 2, 109–118. doi: 10.1002/aur.69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillberg IC, Helles A, Billstedt E, & Gillberg C (2016). Boys with Asperger syndrome grow up: Psychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders 20 years after initial diagnosis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46, 74–82. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2544-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofvander B, Delorme R, Chaste P, Nydén A, Wentz E, Ståhlberg O, … Leboyer M (2009). Psychiatric and psychosocial problems in adults with normal-intelligence autism spectrum disorders. BMC Psychiatry, 9, 1–9. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-9-35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi G, Petty C, Wozniak J, Henin A, Fried R, Galdo M, … Biederman J (2010). The heavy burden of psychiatric comorbidity in youth with autism spectrum disorders: A large comparative study of a psychiatrically referred population. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40, 1361–1370. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-0996-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerns CM, Roux AM, Connell JE, & Shattuck PT (2016). Adapting cognitive behavioral techniques to address anxiety and depression in cognitively able emerging adults on the autism spectrum. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 23, 329–340. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2016.06.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lipinski S, Blanke ES, Suenkel U, & Dziobek I (2018). Outpatient psychotherapy for adults with high-functioning autism spectrum condition: Utilization, treatment satisfaction, and preferred modifications. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1007/s10803-018-3797-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddox BB, & Gaus VL (2018). Community mental health services for autistic adults: Good news and bad news. Autism in Adulthood, 1, 13–17. doi: 10.1089/aut.2018.0006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandell DS, Walrath CM, Manteuffel B, Sgro G, & Pinto-Martin J (2005). Characteristics of children with autistic spectrum disorders served in comprehensive community-based mental health settings. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 35, 313–321. doi: 10.1007/s10803-005-3296-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaidis C, Raymaker DM, Ashkenazy E, McDonald KE, Dern S, Baggs AEV, … Boisclair WC (2015). “Respect the way I need to communicate with you”: Healthcare experiences of adults on the autism spectrum. Autism, 19, 824–831. doi: 10.1177/1362361315576221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor EK, Landsverk J, Aarons G, Chambers D, Glisson C, & Mittman B (2009). Implementation research in mental health services: an emerging science with conceptual, methodological, and training challenges. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 36, 24–34. doi: 10.1007/s10488-008-0197-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymaker DM, McDonald KE, Ashkenazy E, Gerrity M, Baggs AM, Kripke C, … Nicolaidis C (2017). Barriers to healthcare: Instrument development and comparison between autistic adults and adults with and without other disabilities. Autism, 21, 972–984. doi: 10.1177/1362361316661261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum S, Tolbert J, Sharac J, Shin P, Gunsalus R, & Zur J (2018, March). Community health centers: Growing importance in a changing health care system. Retrieved from the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation website: https://www.kff.org/report-section/community-health-centers-growing-importance-in-achanging-health-care-system-issue-brief/

- Roux AM, Rast JE, Anderson KA, & Shattuck PT (2017). National autism indicators report: Developmental disability services and outcomes in adulthood. Life Course Outcomes Research Program, A.J. Drexel Autism Institute, Drexel University: Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- Roux AM, Shattuck PT, Rast JE, Rava JA, & Anderson KA (2015). National autism indicators report: Transition into young adulthood Life Course Outcomes Research Program, A.J. Drexel Autism Institute, Drexel University: Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- Shattuck PT, Narendorf SC, Cooper B, Sterzing PR, Wagner M, & Taylor JL (2012). Postsecondary education and employment among youth with an autism spectrum disorder. Pediatrics, 129, 1042–1049. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shattuck PT, Wagner M, Narendorf S, Sterzing P, & Hensley M (2011). Post high school service use among young adults with autism spectrum disorder. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 165, 141–146. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spain D, Sin J, Chalder T, Murphy D, & Happé F (2015). Cognitive behaviour therapy for adults with autism spectrum disorders and psychiatric co-morbidity: A review. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 9, 151–162. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2014.10.019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tint A, & Weiss JA (2018). A qualitative study of the service experiences of women with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 22, 928–937. doi: 10.1177/1362361317702561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, & Craig J (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19, 349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White SW, Conner CM, & Maddox BB (2017). Behavioral treatments for anxiety in adults with autism spectrum disorder In Kerns CM, Renno P, Storch EA, Kendall PC, & Wood JJ (Eds.), Anxiety in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: Evidence-based assessment and treatment (pp. 171–192). London, UK: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- White SW, Simmons GL, Gotham KO, Conner CM, Smith IC, Beck KB, & Mazefsky CA (2018). Psychosocial treatments targeting anxiety and depression in adolescents and adults on the autism spectrum: Review of the latest research and recommended future directions. Current Psychiatry Reports, 20:82. doi: 10.1007/s11920-018-0949-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JJ, McLeod BD, Klebanoff S, & Brookman-Frazee L (2015). Toward the implementation of evidence-based interventions for youth with autism spectrum disorders in schools and community agencies. Behavior Therapy, 46, 83–95. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2014.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerbo O, Massolo ML, Qian Y, & Croen LA (2015). A study of physician knowledge and experience with autism in adults in a large integrated healthcare system. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45, 4002–4014. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2579-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]