Abstract

Radiotherapy is one of the most common countermeasures for treating a wide range of tumors. However, the radioresistance of cancer cells is still a major limitation for radiotherapy applications. Efforts are continuously ongoing to explore sensitizing targets and develop radiosensitizers for improving the outcomes of radiotherapy. DNA double-strand breaks are the most lethal lesions induced by ionizing radiation and can trigger a series of cellular DNA damage responses (DDRs), including those helping cells recover from radiation injuries, such as the activation of DNA damage sensing and early transduction pathways, cell cycle arrest, and DNA repair. Obviously, these protective DDRs confer tumor radioresistance. Targeting DDR signaling pathways has become an attractive strategy for overcoming tumor radioresistance, and some important advances and breakthroughs have already been achieved in recent years. On the basis of comprehensively reviewing the DDR signal pathways, we provide an update on the novel and promising druggable targets emerging from DDR pathways that can be exploited for radiosensitization. We further discuss recent advances identified from preclinical studies, current clinical trials, and clinical application of chemical inhibitors targeting key DDR proteins, including DNA-PKcs (DNA-dependent protein kinase, catalytic subunit), ATM/ATR (ataxia–telangiectasia mutated and Rad3-related), the MRN (MRE11-RAD50-NBS1) complex, the PARP (poly[ADP-ribose] polymerase) family, MDC1, Wee1, LIG4 (ligase IV), CDK1, BRCA1 (BRCA1 C terminal), CHK1, and HIF-1 (hypoxia-inducible factor-1). Challenges for ionizing radiation-induced signal transduction and targeted therapy are also discussed based on recent achievements in the biological field of radiotherapy.

Subject terms: Cell biology, Genetics research

Introduction

The increasing prevalence of cancer worldwide is a major challenge to the improvement of quality and length of life. According to reports, 975,396 patients were newly diagnosed with cancer in 2012, and there were 358,392 deaths due to cancer in youth globally1. In 2015, the number of identified cancer cases increased to ~17.5 million, and the deaths from cancers increased to 8.7 million globally. Notably, from 2005 to 2015 (an 11-year span), the number of patients with cancer increased by 33%2. In 2016, ~9 million deaths were attributed to cancer, an increase of almost 18% over one decade3. Moreover, in the United States in 2017, there were 1,688,780 newly diagnosed cancer patients and almost 600,920 deaths due to cancer4. These numbers have increased rapidly annually, and in 2018, ~18.1 million newly diagnosed cancer patients and 9.6 million cancer deaths were reported worldwide5. In China, in 2014, there were 3.804 million newly diagnosed cancer patients and 2.296 million cancer deaths, and the statistical results showed that the crude incidence rate and the crude mortality rate were 278.07 per 100,000 people and 167.89 per 100,000 people, respectively6. Furthermore, it is estimated that by 2035, the number of annual cancer deaths will reach 14.5 million because worldwide cancer cases are expected to dramatically increase from 15 million at present to 24 million in the next 20 years3. Moreover, in parallel with the increasing rates of cancer diagnosis and death, the global burden of cancer has gradually increased over the past decade. Based on the Global Burden of Disease Cancer Collaboration announcement, 208.3 million disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) were attributed to cancer globally in 2015. Lung cancer was the top cause of death among males, accounting for 25.9 million DALYs, while in females, breast cancer-attributable deaths were the top cause, accounting for 15.1 million DALYs2. Significant advances in the war against cancer have been achieved over the past decade. For instance, deaths from Hodgkin lymphoma declined significantly between 2005 and 2015 (−6.1%; 95% uncertainty interval: −10.6% to −1.3%), and other cancer deaths, such as deaths from esophageal cancer and stomach cancer, have also significantly decreased over the past decade2. Additionally, through large-action control of tobacco use and human papillomavirus vaccination in females, the burden of cancer in the female population has been substantially decreased in both economically developed and economically developing areas7. Although large-scale implementation of prevention and treatment methods has made these improvements possible, there is still a long way to go in the fight against cancer.

The management of cancer mainly involves surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and the rapidly evolving field immunotherapy8. The most commonly used cancer therapies over the past century include chemotherapy and radiotherapy methods9–12; among these, radiotherapy is widely and predominantly used prior to surgery and other treatment methods13,14. Radiotherapy is defined as the application of radiation for clinical cancer treatment, including external-beam radiation and local radioactive seed implants with the purpose of killing cancer cells or controlling cancer cell proliferation15,16. Radiotherapy is sometimes used alone, but at most times, it is applied in combination with other therapy strategies, such as surgery or oral medicine. Radiotherapy developed rapidly following the discoveries of X-rays by Roentgen, natural radioactivity by Becquerel, and radium by Curie over 125 years ago17. These three fundamental discoveries not only earned the discoverers Nobel Prizes but also founded the research field of radiology, as well as led to the establishment of radiotherapy techniques, such as external-beam radiotherapy with a long source surface distance and brachy therapy with a short-spacing surface space, which are commonly delivered through radium and X-rays18. Three countries, France, America, and Sweden, were the first to adopt radiation for gastric cancer and basal cell cancer treatment19,20. Over the past century, continuous technological improvements in radiotherapy have translated into better clinical practices, not only changing several fundamental concepts but also gradually changing clinical treatment guidelines. For instance, for a long time, radiation with a specific beam energy, such as telecobalt therapy, was applied in the clinic from 50–250 kV to 1.2 MeV, while the linear accelerator was between 6 and 20 MV; now, the computer revolution has made a three-dimensional (3D) approach in complex spaces a reality21. In addition, newly developed therapies based on high linear energy transfer (LET) particles, including protons and heavy ions such as carbon ions, are being used in cancer treatments22–25. However, with the increased usage of radiation not only in cancer treatment but also in medical examination globally, the adverse influence of radiation on the human body has attracted much attention in the public and scientific community, including the subsequent secondary cancer risks and damage to normal tissues after radiotherapy26. Indeed, advances in radiation and radiotherapy are contributing substantially to winning the battle against cancer27–29. Currently, ~50% of cancer patients are subjected to radiotherapy. The combination of radiotherapy, surgery, and other medical treatments has contributed to almost 50% of cancer patients having a long-term survival opportunity. A study performed in Australia reported that among newly diagnosed patients, almost 52% of patients were subjected to radiotherapy, and more than 23% of patients required multiple treatments for a better prognosis30. In China, more than 50% of clinically treated cancer patients have received radiotherapy, which contributed to cure in more than 40% of patients31,32. To standardize quality control, a set of basic guidelines for radiotherapy have been developed, in accordance with the relevant national laws and regulations and referring to relevant international guidelines; These guidelines were announced at the 14th National Congress of Radiation Oncology (CSTRO; available at https://cstro2017.medmeeting.org/cn) meeting32. Moreover, radiotherapy is a conservative treatment with the capacity to affect cancer without body image alteration. Most importantly, radiotherapy is very cost effective. The data released by the International Atomic Energy Agency suggest that radiotherapy is the most economical treatment measure overall, accounting for ~5% of the all-in expenses of patient care for cancers33. Most experts hold that treating cancer using radiation technology is essential and critical for not only saving thousands of cancer patient lives but also saving economic costs in cancer patients; thus, access to radiotherapy should be available globally in the near future 34.

However, radiotherapy is typically accompanied by the unavoidable development of cancer cell resistance to radiation exposure35,36. Radiotherapy resistance (RR), defined as a reduction in the effectiveness of antitumor therapy37, is a major obstacle in cancer treatment. RR either arises within cancer cells when cancer cell genes or phenotypes are altered in response to radiation exposure or is due to the cancer microenvironment protecting cancer cells against the treatment. The former is referred to as intrinsic resistance, while the latter is referred to as extrinsic resistance38. RR leads to cancer relapse, poor treatment response, poor prognosis, decreased quality of life, and increased disease treatment burden. Furthermore, RR induces damage to cancer-adjacent normal tissues, disrupting the physiological and biochemical functions of normal tissue, resulting in symptoms, including radiation-related diarrhea, rectal bleeding, and radiation dermatitis39–41, as well as an increased risk of subsequent secondary cancer26,42–44 or chronic noncommunicable diseases including type II diabetes45,46 or cardiovascular diseases47. Over the past century, to remove the barrier of RR, many studies have been carried out to investigate RR-related regulatory genes, molecules, and signaling pathways to uncover the underlying mechanisms of RR and to develop radiation sensitizers48,49. Currently, two large bottlenecks for successfully improving radiation resistance are as follows: (1) identifying the master regulator of the development and progression of RR and (2) determining how the master regulator can serve as a potential target to overcome RR. In this review, we discuss the promising targets of signaling pathways that can be proposed for cancer radiosensitization and may be translated into clinical radiotherapy targets.

DSBs are a major pattern of RIDD

There are many factors associated with increased RR in cancer cells. These factors include but are not limited to the following: the local cancer microenvironment, membrane signaling sensors, and the patient immune system, gut microbial community50, nutritional status51, and mental health status52. However, among the reported and discovered factors, DNA damage is a primary and intrinsic factor and the most crucial operator in the response to radiation exposure and the orchestration of the subsequent cascade of DNA repair response signaling pathways to control cancer cell cycle arrest and cell fate, i.e., death or survival53. In other words, the ability of radiation to control cancer predominantly depends on radiation-induced DNA damage (RIDD)53; as a result, the DNA damage response (DDR) of tumor cells and the ability of tumor cells to repair DNA damage are essential in determining the outcome of cancer cells.

The genomic integrity of cells is extremely important for cell growth as well as successful transmission of genetic information to the next generation54, However, many types of external or internal genotoxic insults challenge DNA integrity55, forcing the host to evolve and develop compensatory changes to combat DNA damage and maintain genomic integrity56 via several independent or complementary DNA repair pathways, allowing for a fail-safe mechanism whereby the disruption of one pathway will be compensated for by another pathway57. During cancer cell evolution, multiple comprehensive molecular signaling pathways have been developed to face the challenge of radiation stress, and this ability to evolve can contribute to increased cancer cell RR, leading to radiotherapy failure. Moreover, during the process of developing RR, a percentage of cells in tumor tissues not only acquire higher RR but also become more aggressive and are prone to lymph node and distant metastasis58. Thus, enhancement of the cancer response to radiation through DNA damage pathways has been a focus of radiotherapy studies for the past few decades 59–61.

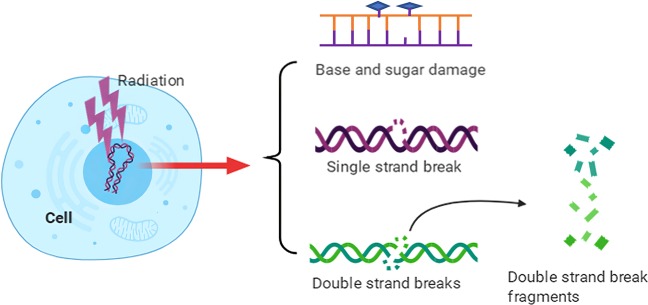

Typically, exposure to ionizing radiation (IR) is often suggested as a treatment for preventing cancer cell proliferation. There are various applications depending on the IR type, such as electromagnetic waves or particles. Currently, several techniques and standard values are well accepted for IR applications; for example, LET is usually performed at between 1 and 10 keV/µm using sources such as X-rays, γ-rays, protons, or carbon ions, while very high values, usually beyond >100 keV/µm, are found in some forms of space radiation62. As reported previously, once the radiation track deposits its energy in the DNA molecules of cancer cells, a fraction of the DNA damage sites will have two or more damages formed within one or two helical turns of DNA63,64. The common DNA damage pattern comprises base and sugar damage, crosslinks, single-strand breaks (SSBs) and double-strand breaks (DSBs), as shown in Fig. 1. Compared to those of SSBs, the patterns of DSBs are more intricate and include simple and complex types, as well as multiple physical characteristics not only referring to the break but also to the kinetics of the ability to repair the break65,66 In terms of simple DSBs, two-ended breaks of DNA may occur as a direct result of radiation, and these have rapid kinetic repair. Complex DNA DSBs, namely, “clustered DNA damage,” are a hallmark of IR and locally consist of more than two instances of oxidative base damage, basic sites, or SSBs around a DSB63,67,68. Compared to simple breaks, complex DSBs are more slowly and inefficiently repaired, resulting in genomic instability69–71. Indeed, the radiation exposure response to DNA damage may vary based on IR type. For instance, high-LET radiation, involving methods such as heavy ion and proton radiation, may preferentially induce clustered damage, a signature of IR; in contrast, isolated, endogenously induced lesions result in a homogeneous distribution67,72. Following irradiation with X-rays or γ-rays, clustered DNA lesions are often 3–4 times more abundant than single-strand damage67,73. Actually, the number of DSBs resulting from high-LET irradiation is much more than that resulting from low-LET irradiation. There is evidence that high-LET irradiation causes almost 500 DSBs/μm3 track volume74. Using 3D-structured illumination microscopy, Hagiwara et al.75 revealed that clustered DSBs could be formed in a space of 1 μm3 by high-LET irradiation; moreover, once these clustered DSBs occur, a higher risk of chromosomal rearrangement and lethality will subsequently develop. More efficient induction of complex clustered DNA damage is a major factor contributing to the higher relative biological effectiveness of heavy ions.

Fig. 1.

DNA damage induced by ionizing radiation. The major types of DNA damage induced by IR include base and sugar damage, single-strand breaks, double-strand breaks, clustered DNA damage, and covalent intrastrand or interstrand crosslinking

Moreover, once a complex DSB forms, the repair occurs slowly, and chromosomal aberrations can cause cell death or delayed mitosis without further repair73,76. Because IR induces genetic instability, RR is expected if cancer cells survive following treatment with IR. Hence, how cellular sensors respond to radiation and how early signal transducers work after IR will be reviewed in the next section based on recently reported evidence to understand the mechanisms of DNA damage signals more deeply and clearly.

Cellular DNA damage sensors and early signal transducers in response to IR

As a signal, DNA damage activates a series of biochemical reactions in response to IR insult, triggering a variety of cellular responses. Nevertheless, the key questions are how the DNA damage signal is sensed and recognized and how the cascade signaling of downstream biochemical reactions is triggered. DNA damage sensors and early signal transducers thus play essential roles in recognizing DNA damage77,78. The ideal DNA damage sensors are the first proteins to contact DNA damage sites, identifying damage signals and triggering cell signaling transduction79–81. Moreover, DNA damage sensors also have the ability to recruit DDR proteins to sites of DNA damage82,83. Signal transducers often play roles as functional partners of DNA damage sensors83,84. As DNA damage sensors and signal transducers usually coexist, it is difficult to classify them. However, signal transducers have kinase activity, transducing the DNA damage chemical signal to induce biochemical modification reactions and triggering the activity of downstream effectors 85.

The first DSB sensor identified from fission yeast was Rad24p by Ford et al. in 199486; this sensor is required for DNA damage checkpoint (DDC) activation and is essential for cell proliferation87. In Schizosaccharomyces pombe, Rad24p is required for some essential functions, as double deletion of its encoding gene is lethal87,88. As a DNA damage sensor, Rad24p is often considered to be the primary DNA damage responder, forming a complex with Ddc1p and Mec3p and triggering cell cycle arrest after DNA damage89. Furthermore, previous studies have revealed that Rad24p associates with Rfc2p-Rfc5p to form replication factor C, functioning in DNA replication or repair and DDC pathways90. In Rad24p-containing compounds, the Rad24p-Rfc2p or Rad24p-Rfc5p complexes can recruit the Rad24p-Ddc1p-Mec3p complex to create a “workshop” similar to the reaction machinery, triggering downstream kinases or effectors such as Rad53p89,91–93. The 14-3-3 isoforms are the mammalian homologs of fission yeast Rad24, functioning in DDC as well as in cell cycle control94. Following the discovery of Rad24p as the DSB sensor, Mec1p and Rad26p were subsequently identified as DNA damage sensors as well89,95. Mec1p has been considered to be the regulator of Ddc1p phosphorylation, a protein responsible for the yeast DDC89. Mec1p and Rad26p, from budding yeast and fission yeast, respectively96, have the characteristics of DNA damage sensors, activating phosphatidylinositol proteins97. The phosphorylation substrates of Mec1p and Rad26p include Ddc1p and Rad9p, another two DNA damage sensors98–100. In general, DNA response mechanisms have been extremely conserved during evolution within both yeast and mammalian cells. Although no effective or idealized DNA damage sensors have been confirmed in mammalian cells, several important molecules were recognized to be associated with DNA damage sensors and, importantly, to mediate and trigger IR-induced DSB signaling responses.

γH2AX

As reported by Siddiqui et al.101, H2AX can respond to DSBs in a phosphorylation pattern at a very early time. H2AX is a variant of the core histone protein H2A; upon DNA DSB occurrence, H2AX is phosphorylated at the S139 site, which forms γH2AX foci. Furthermore, in their review, Siddiqui et al.101 mentioned that γH2AX persisted after exposure to IR under treatment with various radiosensitizing drugs, indicating that this sensor could be used to monitor cancer therapy and to tailor cancer treatments. Using anti-γH2AX monoclonal antibodies and immunofluorescence hybridization techniques to visualize γH2AX localization at sites of DNA damage102,103, even with a very low dose of IR exposure, γH2AX foci can be visualized as well, but once the DNA damage is repaired, the foci are eliminated104,105. Kuo and Yang106 suggested that γH2AX foci represent DSBs in a 1:1 ratio and can be used as a biomarker for DNA damage106. Specifically, the disappearance of γH2AX typically occurs earlier than that of other IR exposure response proteins. Moreover, γH2AX can act as a platform to recruit other DNA repair proteins, such as BRCA1 (BRCA1 C terminal)107, 53BP1 (p53-binding protein 1),108, MDC1109, and Rad51110. Zhang et al.111 reported that glioma stem cells exhibited RR with increased γH2AX-positive cell rates after 6 Gy radiation due to upregulation of the long noncoding RNA (lncRNA) PCAT1. Katagi et al.112 evaluated the effects of histone demethylase inhibition on genes associated with DSB repair in diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma cells and found that the expression of DSB repair genes was significantly reduced, but the level of γH2AX increased and was sustained at a high level. Overall, γH2AX was considered to match the characteristics of a DNA damage sensor more closely than the expression of DSB repair genes. Currently, γH2AX is widely used as a marker to detect radiation-induced DSB repair by immunofluorescent staining of foci or immunocytochemistry113,114.

Nbs1/hMre11/hRad50 complex

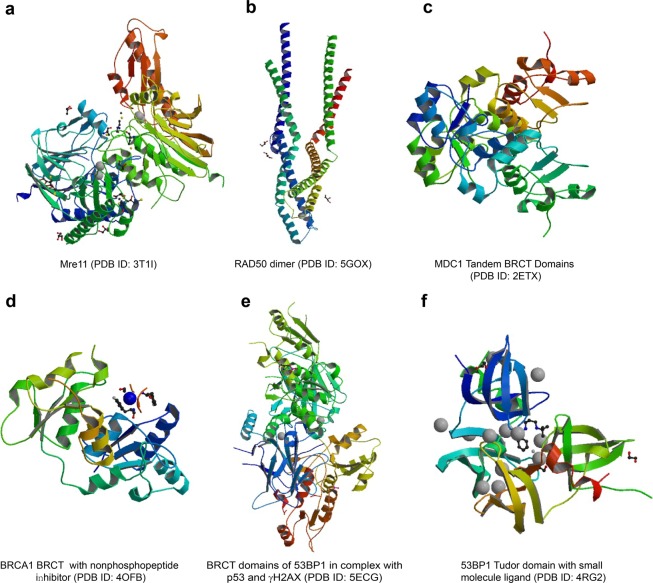

The MRN (Mre11-Rad50-Nbs1) complex, formed by Nbs1, hMre11, and hRad50, was first reported by Carney et al. in 1998115. According to this report, the MRN complex is responsible for linking DSB repair with cell cycle checkpoint functions. Habraken et al.116 suggested that the Nbs1/hMre11/hRad50 complex plays an important role in DNA DSB sensing and the signal transduction initiated by X-ray radiation. Similarly, a study by Kobayashi117 demonstrated that one of the roles of this Nbs1/hMre11/hRad50 complex is to recruit activated ataxia–telangiectasia mutated (ATM) to DNA damage locations, showing that it has the ability to recognize DNA damage initially. Moreover, according to Tauchi et al.118, the hMre11 binding region is necessary for both nuclear localization of the Nbs1/hMre11/hRad50 complex and for cellular radiation resistance; meanwhile, the fork head-associated domain of Nbs1 regulates nuclear foci formation of the multiple proteins in the complex. The hMre11 structure is comprised of an N-terminal core domain containing the nuclease and capping domains and a C-terminal domain containing the DNA-binding and glycine-arginine-rich motif (Fig. 2a). Deletion of the α2-β3 loop (AA84–119) in the hMre11 core structure prevented the formation of a stable hMre11 core dimer and inhibited Nbs1-binding activity119. The structure of the MRN complex contains two major dimerization interfaces that link Mre11, Rad50, and Nbs1 in DNA damage sensing and signaling. One dimerization interface is within the globular domain and involves Rad50 and Mre11. The second is the zinc hook situated distal to the globular domain separated by the antiparallel coiled-coil domains of Rad50. The two parallel coiled-coil domains of RAD50 proximal to the hook form a rod shape (Fig. 2b), which is crucial for stabilizing the interaction of Rad50 protomers within the dimeric assembly120. In the presence of Mn2+ ions, the hMre11 core shows exonuclease and endonuclease activities for 30–50 base spans. Structure and biochemistry analyses indicate that many tumorigenic mutations of hMrell are primarily associated with its Nbs1 binding and partly with its nuclease activities119. A study indicated that heterozygous p.l171V mutation in the Nbs1 gene was found in Korean patients with high-risk breast cancer121. In addition, a persistent increase in radiation-induced Nbs1 foci formation was accompanied by an increased frequency of spontaneous chromosome aberrations122. Another in vitro study indicated that heterozygosity of Nbn, the murine homolog of human Nbs1, contributes to mouse susceptibility to IR-induced tumorigenesis123. Della-Maria et al.124 further identified a novel mechanism in which the Nbs1/hMre11/hRad50 complex interacts with the DNA ligase III α/XRCC1 complex, which is linked with the nonhomologous end-joining (NHEJ) pathway in cancer cells following IR radiation. Ho et al.125 demonstrated that overexpression of the Nbs1/hMre11/hRad50 complex in rectal cancer was associated with RR and poor prognosis. Collectively, although Nbs1 is the phosphorylation target of ATM, the Nbs1/hMre11/hRad50 complex localizes upstream of ATM in the DDR, acting as a sensor.

Fig. 2.

Structures of major DNA damage signal sensors, their main functional domains and their interactions with their partners. The data are from the RCSB database (https://www.rcsb.org/)

Ku (Ku70/Ku80 heterodimer)

Once DSBs occur under IR stress, the primary repair pathways are triggered through two classical pathways, NHEJ and homologous recombination (HR). The NHEJ pathway is triggered via Ku, also known as the Ku70/Ku80 heterodimer, which is preferentially recognizes DSBs126. Depletion of the deubiquitylating enzyme UCHL3 resulted in the reduced chromatin-binding and IR-induced foci (IRIF) formation of Ku80 after DSB occurrence, moderately sensitizing cancer cells to IR127. A recent study by Pucci et al.128 reported nuclear localization of Ku in advanced rectal cancer patients with superior sensitivity to radiotherapy. However, in nonresponder patients, Ku70 was found to move from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, and strikingly, deregulation of Ku70/80 and the Ku70 partner clusterin was extensively associated with RR. Another study found that IR induces the accumulation of autophagosomes, and the radiosensitizing effect of autophagy-related BECN1 deficiency may result from the disruption of nuclear translocation and Ku protein activity, leading to the attenuation of DSB repair in malignant glioma. Similar to other DNA damage sensors, Ku includes a pocket structure. Once DNA damage occurs, Ku can bind to the DNA damage site and immediately embed the DNA break terminus into this pocket129. In a clinical study, the B cells of some B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients were resistant to IR-induced apoptosis; when the B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia cell subset was treated with radiation, the DNA end-binding ability of Ku was significantly increased by two- or three-fold in the radiation-resistant cell subset compared with that in the radiation-sensitive cell subset 130.

MDC1 and 53BP1

DDR alterations are a major cause of cancer cell resistance to radiotherapy131. Both proteins, one named mediator of MDC1 and another known as 53BP1, are also associated with the signaling of DNA DSBs131. MDC1 is a major modular phosphoprotein scaffold that plays an important role in the DDR process. The BRCT domains are crucial modules that mediate the protein–protein interaction in DNA damage sensing and DDR signaling and have been found in a number of DDR proteins, such as MDC1, 53BP1, BRCA1, and Nbs1. In addition to their conserved phosphopeptide recognition and binding functions, BRCT domains are also implicated in phosphorylation-independent protein interactions, poly(ADP-ribose) (PAR) binding and DNA binding132. The architecture of BRCT domains is variable, ranging from a single module to tandem BRCT repeats. Figure 2c–e displays the BRCT domain structures of MDC1, BRCA1, and 53BP1, respectively. Following induction of DNA DSBs, MDC1 is anchored to damaged sites through interaction of its BRCT repeat domain with the tail of γH2AX. Moreover, MDC1 often performs its roles in accompaniment with 53BP1; that is, it can make 53BP1 move to foci under the control of MDC1131,133. The function of 53BP1 in DDR is dependent on its recruitment to the damaged site through 53BP1 tandem Tudor domain-mediated recognition of methylated histone H4 (H4K20me2) and ubiquitinated histone H2A (H2AK15ub). 53BP1 binds with the DSB marker H2AX-pS139 through its BRCT2 domain in vitro and in cells (Fig. 2e), which is necessary for the recruitment of pATM to the damage site134. The Tudor domain of 53BP1 (Fig. 2f) also plays a critical role in the DDR through interactions with BRCT domains. As a 53BP1 regulator, the Tudor-interacting repair regulator (TIRR) directly binds to the 53BP1 Tudor domain and blocks the H4K20me2 binding surface. High-resolution structural analysis shows that the N-terminal region and the L8 loop of TIRR form an extensive binding interface with three loops of the 53BP1 Tudor domain135. TIRR masks the binding surface of H4K20me2. In colorectal cancer cells, following radiation, coimmunoprecipitation analyses showed that Ku70, γH2AX, and MDC1 were colocalized in nuclear foci136. Cairns et al.137 reported that MDC1 could be regulated by Bora. Another study showed that Bora could be phosphorylated by MDC1, leading to abolishment of irradiation-induced MDC1 foci formation, and downregulation of Bora increased the resistance to IR, likely due to a faster rate of DSB repair. A clinical study conducted by Cirauqui et al.138 showed that patients with head and neck cancer with low 53BP1 expression levels treated with radiotherapy had a higher complete response as well as a higher survival time than patients with high 53BP1. Generally, DNA damage induced by IR recruits MDC1 to sites of damage within ~1 min post irradiation, providing a γH2AX-dependent interaction platform for recruiting other DNA damage repair proteins, such as ATM and Nbs1, and the glycolytic enzyme PFKFB3.

BRCA1 and BRCA2

BRCA1 and BRCA2 are clinically correlated with hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. For BRCA1 mutation carriers, the relative risk of breast cancer is 1.19 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.02, 1.39), while for BRCA2 mutation carriers, the relative risk of breast cancer is 1.25 (95% CI: 1.01, 1.55)139. In prostate cancer patients with resistance to prostate-specific membrane antigen-targeting α-radiation therapy, BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes were deleted, and several variants of BRCA1 were detected140. BRCA1 consists of several domains, including an N-terminal region carrying the zinc-binding finger domain RING and two phosphopeptide-binding BRCT domains141,142. Similarly, there are also a few domains for BRCA2, that is, the transcriptional activation domain is located at the N terminus, and the DNA-binding domain is located close to the C-terminal region. Other regions include a conserved helical domain, three oligonucleotide binding folds, and a tower domain141,143. BRCA1 and BRCA2 play a crucial role in the repair of DSBs in the HR pathway144. After exposure to radiation, the BRCA1-RAP80-Abraxas complex binds ubiquitinated histone in response to DNA damage145–147. A recent report showed that BRCA1 could recruit CSB, a member of the SWI2 family, and MRN to form a complex at the late phase of S/G2. This interaction between BRCA1, CSB, and MRN is responsible for MRN-mediated DNA end resection148. In addition, the BRCA1-PALB2 interaction dictates the choice between HR and single-strand annealing149 and is associated with RR. These important roles of BRCA1/2 have suggested them as attractive, valuable, and sensitive diagnostic biomarkers in the prediction of radiotherapy outcomes 34.

The above discussion is associated with the progress of DDR-associated proteins; notably, with an increasing number of in-depth studies, some novel response proteins have been reported. A recent study found that a novel DDR was triggered by MT1-MMP (membrane-tethered matrix metalloproteinase)-integrin β1. This study indicated that suppression of MT1-MMP would improve breast cancer cell resistance to IR therapy 150.

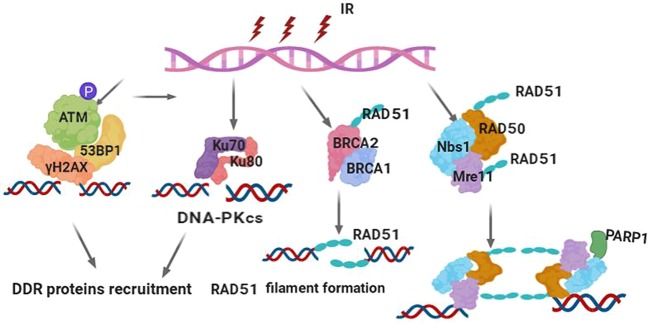

In brief, it is well known that IR-induced DSBs are the most deleterious form of DNA damage, leading to cell death and viable chromosomal rearrangements. As a result, cells have evolved an efficient and rapid DDR to maintain genomic integrity. DNA damage sensors are response proteins that can detect DNA damage; sensor proteins can also recruit transducer proteins to provide signals to enzymes to respond to the break. To date, a series of DNA damage sensor proteins have been identified through numerous studies, including γH2AX, 53BP1, Nbs1, BRCA1/2, and Ku. These DNA damage sensors commonly have the following characteristics: (i) they localize to the sites of DSBs within a few seconds or minutes after IR exposure, forming microscopically visible nuclear domains referred to as IRIF; (ii) sensor proteins can modify the adjacent damage sites by methods such as phosphorylation of γH2AX; (iii) sensor proteins can recruit other proteins to sites of damage to form protein complexes such as the Nbs1/hMre11/hRad50 complex151; and (iv) these DNA damage sensors can also regulate each other. For instance, MDC1 expression was induced by radiation, and the overexpression of MDC1 could activate Nbs1 activity in the presence of DNA damage repair152. These sensors can also be regulated by upstream or downstream proteins. For instance, the human demethylase JMJD1C was stabilized by interaction with RNF8 and recruitment of RAP80-BRCA1, and MDC1 was demethylated at Lys45 through JMJD1C binding to RNF8 and MDC1, promoting cancer cell sensitivity to IR153. Reichert et al.154 reported that following exposure to radiation, a direct relationship between MDC1, γH2AX, and 53BP1 was identified, and higher amounts of DNA breaks were associated with an increased level of γH2AX/53BP1 foci post irradiation. Thus, it is suggested that identification of these sensors after the occurrence of DSBs under IR exposure may be a predictive biomarker in determining radiotherapy outcomes among patients with cancer. γH2AX is a typical example of a marker that has been translated from bench to bedside, and it has been employed in the clinic as a predictive biomarker for radiotherapy sensitivity in some kinds of cancers155. Table 1 presents several primary DNA damage sensors along with their roles and characteristics. Figure 2 illustrates the structures of these sensor proteins or their main functional domains and interacting partners. Figure 3 illustrates the regulation of DNA damage sensors following IR exposure in terms of the common DSB sensors and early signal transducers. Based on the above discussion of the roles and characteristics of DNA damage sensors, these sensors could be used as biomarkers to detect or evaluate DNA damage induced by IR in routine clinical use to determine optimal radiation dosing or as future targets for overcoming RR 156.

Table 1.

Summary of a few main DNA damage sensors induced by IR (human versions are shown)

| Length | Subcellular location | Interaction partners | Mutationsa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| γH2AX | 143 | Nucleus436, chromosome437 | Several other proteins436,438,439 | 141 (Q to N)440 |

| Nbs1 | 754 | Nucleus441, telomere442, chromosome441 | MCM9441; BRCA1, MSH2, MSH6, MLH1, ATM, BLM, RAD50, MRE11, and NBN443 | 28 (R to A); 45 (H to A); 136 (G to E)444 |

| Mre11 | 708 | Nucleus, telomere, chromosome441 | MCM9441,445 | 104 (S to C) in cancer446 |

| Rad50 | 1312 | Nucleus, telomere, chromosome441 | MCM8 and MCM9441; BRCA1447; MSH2, MSH6, MLH1, ATM, BLM, RAD50, MRE11, and NBN443 | 94 (I to L), 127 (V to I); 191 (T to I), 193 (R to W), 224 (R to H), 315 (V to L), 469 (G to A)448 |

| MDC1 | 2089 | Nucleus, chromosome449 | MRE11, RAD50, and NBN; CHEK2, the BRCA1-BARD1 complex, SMC1A and TP53BP1, ATM and FANCD2450,451 | 58 (R to A) and 1840 (K to R)451 |

| 53BP1 | 1972 | Nucleus452, chromosome453 | p53/TP53454; H2AFX438; CHEK2455; RIF1456; PAXIP1, IFI202A, and SHLD2457 | 6, 13, 25, 29, 105, and 166 (S to A) |

| BRCA1 | 1863 | Nucleus458, cytoplasm459 | BARD1, UIMC1/RAP80, ABRAXAS1, BRCC3/BRCC36, BABAM2, and BABAM1/NBA1460,461; RBBP8462; CHEK1, CHEK2, BAP1, BRCC3, AURKA, UBXN1, and PCLAF463; H2AFX436 | 26 (I to A)464; 308 (S to N)465; 1143 (S to A) and 1280 (S to A)466; 1692 (D to N) and 1749 (P to R)467 |

aAvailable from https://www.uniprot.org/

Fig. 3.

Damage sensors and their functional complexes in response to DNA double-strand breaks. (1) Upon DSB occurrence, the core histone protein variant H2AX is instantaneously phosphorylated on its S139 position to form γH2AX foci, which can be detected at the DSB site. γH2AX provides a platform to recruit DDR proteins, such as 53BP1, MDC1, and ATM, to DSBs to initiate DDR signal transduction. (2) DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK), composed of Ku70, Ku80, and the catalytic subunit DNA-PKcs, is a classical DSB-sensing and -binding complex. DSB binding by DNA-PK protects the broken DNA end from degradation by endogenous nucleases; on the other hand, it recruits and activates the downstream components in the NHEJ pathway of DSB repair. (3) BRCA1 and BRCA2 are key proteins involved in DSB binding and initiating the HR pathway and later repair processing. BRCA2 directly recruits RAD51 to sites of DNA damage through interaction with conserved BRCT motifs to stabilize the RAD51 nucleoprotein filament on the ssDNA end of DSBs. Following end resection of the DSBs, BRCA1 activates RAD51 to promote gene conversion of homologous recombination. (4) The MRN complex (Mre11-Rad50-Nbs1) is the primary sensor of DSBs and localizes to damage sites to initiate end resection and HR processing. The MRN complex also promotes the recruitment and activation of ATM and PARP-1. PARP-1 produces poly(ADP-ribose) polymers and extends DNA damage signaling

Signaling pathways of DDR and repair

IR-induced DNA damage repair

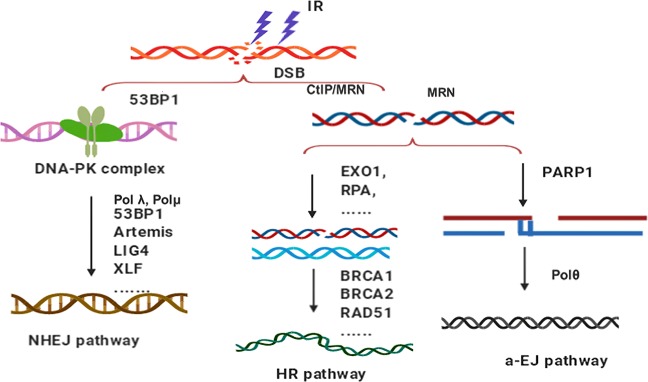

IR kills cancer cells via the induction of DSBs in cancer cell genomic DNA, resulting in genomic instability, apoptosis, cell cycle checkpoint alteration, or postmitotic death. During IR treatment, cancer cells evolve personalized DNA damage repair mechanisms against IR insults for survival66. The induction of DNA mechanisms required to realize the effects of IR has been referred to as “hormesis”157. It has been reported that three different primary pathways evolved to process DSB repair: the HR-based pathway, NHEJ, and alternative end joining (Fig. 4). The goal of these repair pathways is to handle different forms of DNA lesions, eventually achieving DSB removal and maintaining genomic integrity 158.

Fig. 4.

The pathways of DNA double-strand break repair. The nonhomologous end-joining (NHEJ) pathway is an error-prone repair pathway that functions through the cell cycle. The homologous recombination pathway is an error-free repair pathway that requires intact homologous DNA as a repair template and is active in the later S and G2 phases. The alternative end-joining (a-EJ) pathway, which repairs DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs), is initiated by end resection that generates 3′ single strand

Understanding the underlying mechanisms by which DNA damage is repaired in cancer cells post IR treatment would facilitate overcoming RR159. For instance, eurycomalactone, an active quassinoid isolated from Eurycoma longifolia Jack, markedly delayed the repair of radiation-induced DSBs in non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells160. Koval et al.157 reported that a protective system could be activated among cancer cells in response to IR, leading to increased resistance to subsequent exposure to IR, and moreover, chronic exposure to γ-rays increased the expression of the mus210, mus219, and mus309 genes, even after 56 days, in Canton-S flies. Although the development of genome-wide sequencing techniques has allowed scientists to identify the molecular mechanisms of the radiation-induced adaptive response, including the Notch, tumor growth factor-β, mammalian target of rapamycin, and Wnt signaling pathways, the detailed mechanism of cancer cell defense in IR-induced hormesis remains unclear.

DNA DSB repair pathways

In the history of studying the DSB repair pathway, the HR pathway was the first to be discovered161. The HR pathway was named due to the close vicinity of homologous strands during mitosis. HR is specifically triggered in cells in the later S and G2/M phases162. In the 1980s, the second DSB repair pathway, the DNA end-joining pathway, was discovered. In contrast to HR, NHEJ is triggered in the G0/G1 phase as well as G2/M163. Nevertheless, NHEJ is supposed to be predominant in mammalian cells compared with microorganisms164,165. Since the term homologous was used previously in the HR pathway by radiobiological community, the second discovered pathway was defined as NHEJ166,167. However, some radiobiologists disagree with the naming approach and have suggested the existence of other DSB repair pathways because studies have revealed that in cancer cells with extreme radiotherapy sensitivity, both the HR and NHEJ pathways exist, suggesting that other repair pathways may also be functioning168.

Many studies have indicated that HR is essential for accessing the redundancy of genetic information that exists in the form of sister chromatids or homologous chromosomes when both strands of the DNA double helix are compromised169. When a chromosome is insulted by IR exposure, the DDR cooperates with cellular signaling pathways to maintain genomic stability and ensures cell survival170,171. As shown in Fig. 4, for the HR pathway, the DSB is resected from 5′ to 3′ on one strand of the DSB end, creating terminal 3′-OH single-strand DNA (ssDNA) tails169. In other words, during the process of HR repair, a homologous sequence is needed as the template172, aiming to restore HR accurately. Moreover, both one- or two-ended DSBs can be repaired through the HR pathway, and in particular, messy DNA breaks with covalently attached proteins can be repaired through HR169,173. Compared to NHEJ, HR is more complicated, involving numerous enzymes and proteins, but is more accurate and error free174. In summary, HR is slow, requires a template, is highly accurate, is only initiated at the later S and G2 phases, can repair both one- and two-ended breaks, and can repair protein-blocked ends175,176. The HR pathway for DSB repair has also been used as a genome editing tool. For instance, the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-Cas9 technique is now exploited in genome editing and is considered an incredible opportunity for curing genetic diseases177,178. Furthermore, the HR pathway is associated with RR. A recent study by Jin et al.179 found that Deinococcus shows high resistance to IR exposure due to a combination of passive and active defense mechanisms, such as self-repair of DNA damage through the HR pathway. Lopez Perez et al.180 reported that glioblastoma cancer cells exposed to carbon ions initiated the HR repair pathway with strong and long-lasting cell cycle delays, predominantly in G2, with a high rate of apoptosis. Many cancer cells aberrantly express the cancer/testes antigen HORMAD1. Knockout of HORMAD1 in cancer cells resulted in increased sensitivity to IR treatment, and the HR-mediated repair pathway targeting IR-induced DSBs was attenuated in HORMAD1-knockout cancer cells181. In addition, the cysteine protease cathepsin B contributes to RR by enhancing HR in glioblastoma182.

The basic mechanism of the CRISPR-Cas9 editing approach is to induce a site-specific DSB via bacteria, and the selection of the DSB repair pathway dictates the outcome of the editing183. That is, imprecise repair via the NHEJ pathway contributes to insertion or deletion mutations at the break sites; by contrast, repair via the HR pathway enables activation of the recombination machinery, which consequently deals with DNA segments or corrects pathogenic mutations184,185. The initiation of the HR pathway primarily occurs at the DNA break location, which function as ssDNA that can be used for locating a homologous dsDNA sequence. This sequence can then be used as a template for largely accurate repair. Meanwhile, extended DNA end resection contributes to nonligatable DNA breaks and hampers end joining; consequently, DNA end resection is dominant186–188. Hence, HR is initiated only when a repair template exists, which can limit the potential for illegitimate recombination. In general, misregulation of the HR repair pathway is critical for the generation of genome rearrangements in numerous cancers. It is important and necessary to further elucidate the details of HR, the roles of the relevant proteins, and how these proteins are regulated. We believe this will be an exciting direction in the future.

During the process of NHEJ, Ku first moves to and binds with DNA ends, and the binding shape is similar to a ring encircling the duplex DNA. This binding shape avoids DNA end degradation and recruits other proteins, such as DNA-dependent protein kinase, catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs). After ligation of the broken DNA ends by the XRCC4-XLF complex and DNA ligase IV (LIG4), DNA-PKcs tethers with the Ku70/Ku80 ends172. NHEJ also plays an important role in cancer cell RR. Compared to HR, NHEJ generally has a rapid response, is template-independent, is often mutagenic, is cell cycle-independent, can only repair two-ended breaks, and cannot repair protein-blocked ends189,190. Bylicky et al.191 reported that increased expression of Ku70 may be a key factor for RR in normal human astrocyte cells; following X-ray radiation, the cells displayed a robust increase in the expression of NHEJ repair pathway-related enzymes within 15 min of radiation. Mu et al.192 reported that mangiferin induces sensitization of glioblastoma cells to radiotherapy via inhibition of the NHEJ repair pathway through regulation of various proteins, such as phosphorylation of ATM, 53BP1, and γH2AX. Wang et al.193 found that the lncRNA LINP1 facilitated DNA damage repair by decreasing the levels of cleaved caspase-3 and poly[ADP-ribose] polymerase (PARP) in response to IR and decreased the radiosensitivity of cervical cancer cells through the NHEJ pathway. These data show that the NHEJ repair pathway plays critical roles in controlling RR.

In cancer cells, both HR and NHEJ are important pathways for repairing DSBs caused by IR insult. For instance, the MEK1/2 (mitogen activated protein kinase kinase 1/2) inhibitor GSK212 mediates radiotherapy sensitivity by functionally repressing both HR and NHEJ, leading to delayed DNA repair and the persistent increased expression of γH2AX194. Thus, in clinical applications, upregulation of DNA repair pathways is recognized as a primary acquired mechanism through which cancer cells may become RR. Accordingly, radiotherapy sensitization strategies functioning via inhibition of IR-induced DNA repair and functional downregulation of the activity of both the HR and NHEJ pathways are expected to be applied clinically to control cancer. Figure 4 illustrates the repair pathways for DNA DSBs.

Activation of cell cycle checkpoints

The cell cycle is essential for cell growth, proliferation, and reproduction. The cell cycle allows cellular components to be replicated and delivered to the next generation of cells195. The cell cycle is a complex process that involves a large number of regulatory proteins, including cyclin family proteins, cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs), CDK inhibitors (CKIs), including Ink4 family members (p15, p16, p18, and p19) and Cip/Kip family members (p21, p27, and p57), CDC25 isoforms, p53 family proteins, and MDM2196. Over the past few decades, studies of the cell cycle have attracted extensive attention in the scientific community. Generally, in eukaryotes, the cell cycle can be divided into four phases, termed G1 (the first gap period), S (synthesis, the phase in which DNA is replicated), G2 (the second gap period), and M (mitosis)197. Cell cycle checkpoints, which define the end product of a molecular regulatory pathway or signaling cascade, ensure an ordered succession of cell cycle events, and when perturbed, lead to cell cycle arrest198; these checkpoints are critical for protecting cells from progressing into the next phase of the cell cycle before prior molecular events, such as DNA damage and spindle structure disruption, have been resolved199. If premature entry into the next cell cycle phase occurs without checkpoint review, catastrophic consequences or cell death may occur200. Cell cycle arrest is caused by depletion of some key proteins regulating this process. The cell cycle can be thought of as similar to a wheel, while the cell cycle checkpoints are the spokes of the wheel. The running of the wheel normally can maintain the doubling of cellular components and their accurate segregation into the next generation of cells. The spokes of the wheel are the regulators of the cell cycle and play an essential role in the function of checkpoints.

Cell cycle checkpoints are classified as DNA structure checkpoints (DSCs, or DDCs) and spindle assembly checkpoints (SACs). IR-induced DNA damage is one of the major triggers for the activation of a number of DNA structure checkpoints, leading to cell cycle arrest at various points in G1, S, and G2/M201,202. The SAC functions in the mitotic phase. In summary, IR-induced DSBs are a key signal for activation of cell cycle arrest at several cell cycle stages: termed G1/S arrest, S-phase arrest, G2/M arrest, spindle checkpoint arrest, and M-phase arrest.

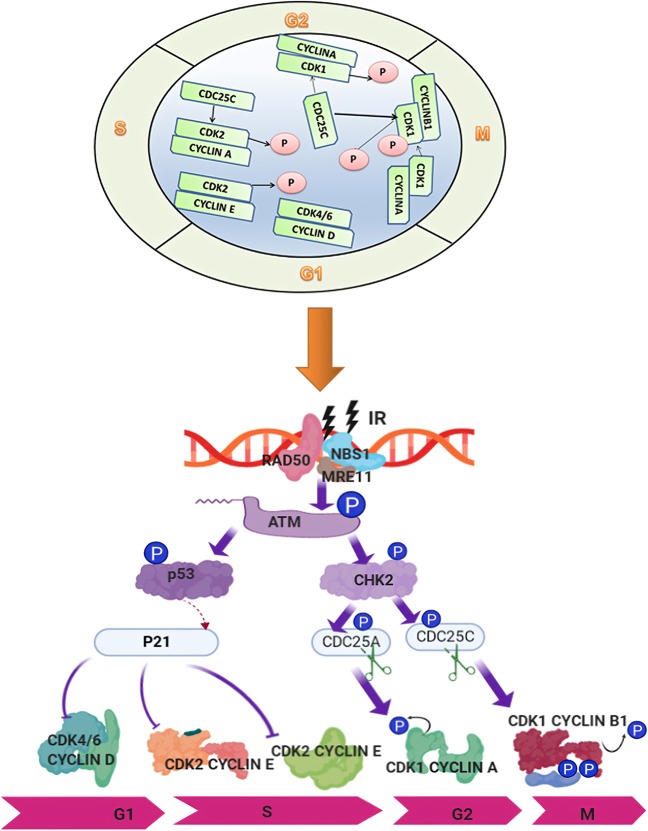

In G1/S arrest, cyclin D recruits CDK4 or CDK6 to form the cyclin D-CDK4/6 complex, which phosphorylates pRB, leading the transcription factor E2F to be released from pRB and to activation of cyclin E transcription. Cyclin E combines with CDK2 to form a complex, further phosphorylating pRB in a positive feedback loop and enhancing S-phase activities, promoting the transition from G1 to S phase203–206. However, exposure to IR may contribute to interruption of the G1/S transition, resulting in S-phase arrest. In theory, G1/S arrest would give cells with radiation exposure more time to perform DNA damage repair207–209. Previous studies have indicated that p53, a famous transcription factor, regulates the cell cycle210,211, especially by monitoring G1 and G2/M checkpoints195. G1 arrest has been reported to be associated with p53 status. Nagasawa et al.212 revealed the absence of G1/S arrest in cancer cells expressing normal p53 synchronized by mitotic selection following irradiation. Fabbro et al.213 found that p53 was phosphorylated and regulated by a series of proteins. First, BRCA1 is phosphorylated at two sites, Ser1423 and Ser1524, based on the regulation of ATM/ATR (ATM and Rad3-related), and then, ATM/ATR is activated by phosphorylation of BRCA1 to phosphorylate p53 at the Ser15 site. Consequently, phosphorylation of p53 serves to monitor G1/S arrest by inducing p21, which is reported to be a CDKi. Yoon et al.214 compared the G1 population difference post IR between colon cells with p53 (+/+) or without p53 (−/−) expression, and the results illustrated that the G1 population was significantly abolished in p53 (−/−) cancer cells compared with that in p53 (+/+) cancer cells post IR. They also found that KLF4 mediated p53 activation to control G1/S arrest following irradiation, indicating that p53 regulation in the IR response in cancer cells is complex and that p53 is a key factor in the process. Thus, recovery or activation of p53 could be a strategy for overcoming RR. Jiang and Wang215 showed that downregulation of mitochondrial transcription factor A increased the radiotherapy sensitivity of cancer cells through the p53 signaling pathway. It has now been confirmed that when DNA damage occurs in G1 cells, the G1/S checkpoint can be triggered via at least two signaling pathways, the ATM/p53/p21 and the ATM/CHK2/CDC25C pathways216. For instance, post irradiation, ATM is activated, and ATM phosphorylates p53 and MDM2, promoting dissociation of p53 from MDM2 and inhibiting p53 translocation from the nucleus to cytoplasm; on the other hand, CHK2 is activated, which phosphorylates and stabilizes p53, and the increased level of p53 triggers the transcription of downstream genes such as p21, contributing to G1/S arrest217–219. Compared to the ATM/p53/p21 pathway, the ATM/CHK2/CDC25C pathway induces rapid signaling in response to DNA damage220. G1/S arrest is induced when CDC25C is degraded via ATM/CHK2 after IR-induced DNA damage 221–223.

During the IR-induced cell injury response, S-phase arrest is activated to inhibit DNA synthesis224. Various patterns, including DSBs, DNA crosslinks, and DNA adducts, can trigger S-phase arrest195,225. Deficiencies in S-phase checkpoints accelerate DNA synthesis under the condition of DSBs, an abnormal phenomenon that can occur in cells from patients with ataxia–telangiectasia (A–T), Nijmegen breakage syndrome, or other chromosome syndromes225,226. According to previous studies, ATM mediates S-phase checkpoints via three parallel signaling pathways: ATM/CHK2/CDC25a/CDK2, ATM/MRN/SMC1, and ATM/MRN/RPA225,227. In addition, post IR, ATM phosphorylates both Nbs1 and CHK2, leading to S-phase checkpoint activation. Ultimately, the distinct steps of DNA replication are suppressed227. Regulation of the S-phase checkpoint is complex, involving multiple pathways; thus, determining whether cancer cells are dependent on one, both, or neither of these intra-S-phase checkpoints in response to IR is necessary.

G2/M arrest prevents cells from entering the M (mitosis) phase in the presence of DSBs224. G2/M arrest often occurs at 0.5 to 4 h post exposure to IR in mammalian cells and then resolves228. The higher the IR dose, the more obvious the G2/M arrest, and the more delayed the recovery effect; sometimes recovery is impossible, and cell death occurs as a result of mechanisms such as mitotic catastrophe. However, it should be noted that the level of cell cycle arrest and recovery time differ in different cell lines. In addition, a deficiency in some genes involved in regulating G2/M arrest, including PLK1, ATM, and CHK1, alters the cell cycle response to IR-induced DNA damage229,230. G2/M arrest is also associated with RR. Gogineni et al.231 found that when meningioma cells were subjected to IR, G2/M arrest could be triggered quickly, and the key event in the underlying mechanism was the phosphorylation of CHK2, CDC25C, and CDC2; this phosphorylation interferes with CHK2 activation and the cyclin B1/CDC2 interaction, resulting in permanent arrest followed by apoptosis. Aninditha et al.232 compared the effects of heavy ions and photons on malignant melanoma cell G2/M arrest and found that heavy ions caused a greater increase in G2/M arrest than photons, showing that heavy ions have better properties for improving RR for malignant melanoma cells than photons. A study conducted by Wang et al.233 showed that IR increased colorectal cancer cell sensitivity to the melatonin by triggering G2/M arrest as well as downregulating the expression of ATM, a key mediator in DSB repair. Peng et al.228 showed that in response to IR, radioresistant cells exhibited a recoverable G2/M phase during a prolonged cell cycle. These data validate the potential of targeting G2/M-related proteins involved in the response to IR to control RR in cancer patients. Figure 5 illustrates the regulation of cell cycle checkpoint-related proteins in the response to IR.

Fig. 5.

Functional complexes of cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) and the signaling pathways involved in the regulation of cell cycle checkpoints in response to IR-induced DNA damage. CDK4/6/cyclin D promotes progression through the G1 phase. In late G1, the active CDK2/cyclin E complex promotes the G1/S transition. The CDK2/cyclin A complex promotes progression through S phase. The CDK1/cyclin A complex regulates progression through the G2 phase in preparation for mitosis. The G2/M-phase transition is initiated and promoted by the CDK1/cyclin B complex. The activity of CDK1/cyclin B is tightly maintained by the CDC25C phosphatase. Following DSB induction by IR, ATM is activated by the MRN complex, which then phosphorylates p53. Activated p53 transactivates the expression of p21Cip1, which inhibits CDK2, consequently inducing G1/S arrest. On the other hand, ATM phosphorylates and activates CHK2, which in turn phosphorylates and inactivates CDC25C; the latter is then cytoplasmically sequestered by 14-3-3 proteins. Consequently, the inhibitory phosphorylation of CDK1 by Wee1 and Myt1 on Tyr15 and Thr14 is maintained, and G2/M arrest is induced

Targeting DNA damage repair to sensitize cancer cells to radiation

DSBs generated by radiotherapy are the most efficient molecular events damaging and killing cancer cells; however, the inherent DNA damage repair efficiency of cancer cells may cause cellular resistance and weaken the therapeutic outcome. Genes and proteins involved in DSB repair are targets for cancer therapy since their alteration, interaction, translocation, and regulation can impact the repair process, making cancer cells more resistant or more sensitive to radiotherapy. Thus, targeting DNA damage repair as a method to sensitize cancer cells to radiotherapy is a promising therapeutic strategy for the precise and effective treatment of cancer patients. In this section, recently reported literature regarding some of the most important DDR-associated proteins involved in RR is reviewed and discussed.

Targeting DNA-PKcs

DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK) is first introduced in this section due to its importance and because it has been intensively studied previously in the NHEJ pathway.234. It has been confirmed that DNA-PKcs can identify DSBs post-IR insult and facilitate “messy” broken end processing and DNA ligation by recruiting the proteins responsible for DNA damage repair processing and ultimately ligating the broken DNA ends235,236. DNA-PKcs was first discovered due to the observation that dsDNA can modulate the phosphorylation of a series of proteins237. In early published reports, DNA-PKcs was associated with repairing DSBs through the NHEJ pathway; however, with further study, it was illustrated that DNA-PKcs has multiple functions, including selection of NHEJ and HR repair pathways238–241, regulation of cell cycle checkpoints242–245, and maintenance of telomeres245–247. As one of the largest family members of the PIKK (phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-related kinase) family, DNA-PKcs consists of 4128 amino acids248. During the past few decades, extensive studies have been conducted to reveal how DNA-PKcs works in DDR pathways71,249. Briefly, DNA-PKcs and other proteins, including Artemis and XLF, are recruited by Ku to form a DNA-PK functional complex250. Then, DNA-PKcs phosphorylates components of the NHEJ machinery, and autophosphorylation or ATM-catalyzed phosphorylation at Thr2609, Ser2056, and Thr2647 allows for DNA end processing251–253. Cells harboring decreased levels of DNA-PKcs showed increased sensitivity to IR compared to control cells254. In the HR pathway, replication protein A coupled with the phosphorylation of p53 affected HR in a mechanism mediated by DNA-PKcs 255.

Our research team has focused on studying DNA-PKcs for almost three decades. We have reported multiple essential DNA-PKcs functions and mechanisms in the IR-induced DDR. For instance, cyclin B1 ubiquitination was activated and its protein stability was affected by DNA-PKcs via the CDH1-APC pathway256. We also found that radioresistance may be a result of the effect of c-Myc on ATM phosphorylation and DNA-PKcs kinase activity257. Furthermore, DNA-PKcs associates with PLK1 and contributes to chromosome segregation and cytokinesis242. We demonstrated the effects of anti-DPK3-scFv on radiosensitization by targeting DNA-PKcs258. Another discovery was that Ku could recruit DNA-PKcs and CHK2245, and a dominant role for DNA-PKcs in regulating H2AX phosphorylation in the post-IR-induced DDR was identified259. Moreover, suppression of DNA-PKcs changes multiple signal transduction-associated genes at the transcriptional level and eventually affects cell proliferation and differentiation260. Our studies further identified that DNA-PKcs is a critical component of DNA damage repair pathways.

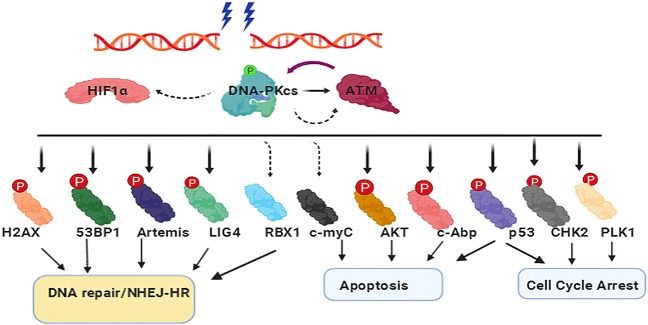

To date, DNA-PKcs is the best known regulator/mediator of the IR-induced DDR; furthermore, it has been implicated as an emerging intervention target in cancer therapy, particularly in radiotherapy or genotoxic chemotherapy261. More recently, the targeting of DNA-PKcs has been used in cancer radiotherapy. According to Liu et al.262, suppression of DNA-PKcs was markedly abrogated by the IR-induced transcription factor hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α), leading to IR-induced decreases in migration and invasion and enhanced radiotherapy sensitivity in glioblastoma. Mamo et al.263 reported that inhibition of DNA-PKcs sensitized human osteosarcoma cells in response to IR. Targeting DNA-PKcs with various inhibitors has been reported to be effective for potentiating radiotherapy and has been proposed as an effective strategy to improve cancer patient outcomes264. In recent decades, significant progress has been made in the development of large amounts of DNA-PKcs inhibitors from basic experiments, and many treatments have already been tested in clinical trials or applied in clinical therapy. Wortmannin was the first identified DNA-PKcs inhibitor265, but it lacks specificity, and its in vivo toxicity makes it difficult to use in clinical applications. Another nonselective inhibitor is LY294002, which has a similar structure to wortmannin266. Davidson et al.266 summarized a series of DNA-PKcs inhibitors in their review, which included LY294002, NU7026, NU7441, IC86621, IC87102, IC87361, OK-1035, SU11752, vanillin, NK314, and IC486241. LY294002 is a competitive inhibitor that binds reversibly to the kinase domain of DNA-PK267. Compared to nonselective inhibitors, NU7026 is more selective for DNA-PKcs268. NU7441 is a strong inhibitor of DNA-PKcs. It could improve RR in liver cancer cells by participating in DDR pathways and activating cell cycle arrest269. IC86621, IC87102, and IC87361 are inhibitors based on the LY294002 structure. These inhibitors promoted increased sensitization to IR and decreased repair of spontaneous and IR-induced DSBs270. Vanillin, derived from vanilla pods, showed selective inhibition of DNA-PK and specifically affects NHEJ271. In our laboratory, we identified a vanillin derivative, BVAN08, as a DNA-PKcs inhibitor that can efficiently induce autophagic cell death and mitotic catastrophe in radioresistant cancer cells. In addition to DNA repair inhibition, cancer cell killing by BVAN08 is related to destruction of the c-Myc oncoprotein and G2/M-phase function272,273. In addition to these inhibitors, several novel inhibitors have been recently discovered and published. M3814, an oral DNA-PK inhibitor, showed preclinical activity274. Sun et al.275 demonstrated that M3814 effectively blocked IR-induced DSB repair. AZD7648 is reported to be a potent and selective DNA-PKcs inhibitor, enhancing radiation sensitivity276. VX-984, a novel drug that was developed as a selective inhibitor of DNA-PKcs, enhanced cell death during radiotherapy277. Doxycycline, the first US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved DNA-PK inhibitor, reduced DNA-PKcs protein expression by ~15-fold and functioned as a radiosensitizer in breast cancer cells278. A recent study showed that phosphorylation of H2AX and KAP1 could be facilitated by DNA-PKcs, resulting in chromatin decondensation and quickly recruiting the DDR complex to DNA damage sites 279.

Targeting ATM/ATR

ATM was discovered during a clinical case observation; that is, in 1967, Gotoff et al.280 reported that a patient with a rare inherited autosomal-recessive genetic A–T condition exhibited immunodeficiency. A previous study showed that patients with A–T were more sensitive to radiotherapy than patients without A–T281. Subsequently, a study indicated that not only G1/S arrest but also G2/M arrest could not be activated in A–T cells after IR exposure282. Later work identified the ATM gene, with a transcript size of 12 kb283. ATR, originally discovered in budding yeast, has been found to exhibit S and G2 checkpoint deficiency284. Later work identified the C-terminal phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)-like kinase domain while cloning the MEC1 gene because the sequence was similar to Mec1/Esr/Sad3 and fission yeast Rad3285. In 1996, Bentley et al.286 identified that ATR could functionally enhance esr1-1 radiation sensitivity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. With the discoveries of ATM and ATR, multiple lines of scientific enquiry converged.

Both ATM and ATR are large polypeptides, and their domain organizations are similar, but their structural features are generally different126. One of the main roles of ATM and ATR is that they can phosphorylate serine or threonine residues according to some biochemical reports287. ATM and ATR share certain substrates and have some overlapping functions. ATM is activated and recruited to DSB sites by the MRN complex, which serves as a DNA damage sensor, while ATR is activated and recruited to DSB sites with its stable binding partner ATRIP (ATR-interacting protein)288. Previous studies have demonstrated that ATM is a master regulator of the cellular response to DSBs289. Indeed, the major ATM function is that it can initiate a cascade for the DSB signaling response, resulting in the phosphorylation of almost hundreds of substrates when cells are undergoing the DDR290. For instance, ATM activates CHK2 kinase and phosphorylates multiple sites, triggering apoptosis, and cell cycle arrest, and deficiency of ATM-mediated signaling reactions causes sensitization of cells to IR291. A recent study demonstrated that resting peripheral blood lymphocytes were more sensitive to radiotherapy when ATM was inhibited than when it functioned normally. Meanwhile, it was found post IR that ATM phosphorylation activity was decreased through stimulation of CD3/CD28292. Moreover, the synergistic relationships among three key proteins, ATM, ATR, and DNA-PKcs, have been found to present different functions with low- or high-dose IR. When subjected to low-dose IR, the G2 checkpoint is tightly regulated by ATM and ATR mainly through interactions with another cell cycle mediator, CHK1. However, when subjected to high-dose IR, the ATM and ATR complex becomes relaxed. Both ATM and ATR can affect the G2 checkpoint independently, resulting in DSB end resection293. Thus, some experts, such as Blackford and Jackson126, suggest that ATM, ATR, and DNA-PKcs react with each other, forming a complex and mediating DDR.

As key mediators of the DDR, the ATM and ATR kinases have been suggested to have extreme potential for improving radiotherapy outcomes because of their abilities to promote DDR and mediate cell cycle arrest294. To date, reported ATM inhibitors include caffeine, wortmannin, CP-466722, KU-55933, KU-60019, and KU-559403. Caffeine was first reported to sensitize cells to IR in 1995, and an increased radiosensitizing effect was observed in cells with p53 deficiency295. Wortmannin targets both ATM and DNA-PKcs to increase cell radiosensitivity. KU-55933 is potentially a selective ATM inhibitor. It confers marked sensitization to IR296. KU-60019 is an analog of KU-55933, inhibiting ATM downstream signaling and sensitizing cells to IR in vitro297. Glioblastoma-initiating cell-driven cancers with low p53 expression and high PI3K expression might be effectively radiosensitized by KU-60019298. Reported ATR inhibitors include schisandrin B, NU6027, NVP-BEZ235, VE-821, VE-822, AZ20, and AZD6738. Schisandrin B, reported in 2009, is a natural extract from the medicinal herb Schisandra chinensis. In human lung cancer cells treated with ultraviolet light, it could inhibit the activity of ATR phosphorylation substrates and abrogate G2/M cell cycle checkpoints299. NU6027, a nonselective inhibitor, has been shown in a few cancer cell lines to have potential for improving IR-induced RR. NVP-BEZ235, another reported potential and effective inhibitor, caused marked radiosensitivity in Ras-overexpressing cancers. VE-821 has been shown to be a potent ATR inhibitor by inhibiting phosphorylation of the ATR downstream target CHK1 at Ser345 in the colorectal cancer cell line HCT116. As a key inhibitor, VE-822 has been found to have potential because of its ability to increase persistent DNA damage. VE-822 was also reported to decrease HR for cancer cells post IR300, suggesting that this inhibitor is promising for overcoming RR in patients with advanced pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. AZ20 is another inhibitor of ATR301. A phase I study of AZD6738 was conducted to analyze the tolerability, safety, and biological effects of palliative radiotherapy in cancer patients in the United Kingdom in 2019302. These ATM and ATR inhibitors were identified based on a broad range of preclinical studies and extensive literature; however, the potential for increased normal tissue toxicity is likely to be an important concern, and identifying their selective effects in concert with radiotherapy will require further investigation.

Targeting DNA LIG4

DNA LIG4 is an essential DNA repair component in the radiation-induced NHEJ pathway303. Commonly, LIG4, XRCC4, and Cernunos-XLF are recruited to the breakage site and temporarily attach to the ends of the DNA to ensure ligation of the DSB304. LIG4 deficiency leads to a rare primary immunodeficiency called LIG4 syndrome305. Patients who have been diagnosed with LIG4 syndrome present increased sensitivity to radiotherapy, but they also have an increased risk of neurological abnormalities and bone marrow failure, as well as increased susceptibility to cancer306. The symptoms of LIG4 syndrome show that LIG4 is vital in the DDR. Numerous studies have reported that mutations in LIG4 confer clinical radiosensitization. Riballo et al.307 indicated that mutation of LIG4 impaired the formation of an adenylate complex in addition to reducing the rejoining activity. Furthermore, healthy participants with the rs1805388 polymorphism of LIG4 were more sensitive to radiation based on γH2AX foci analysis than healthy participants without this polymorphism308. Nevertheless, a Lig4−/−p53−/− cell line had a higher sensitivity to high-LET radiation than a Lig4+/+p53−/− cell line, suggesting that LET-induced DNA damage is partially repaired through LIG4309 McKay et al.310 screened tissues from a unique bank of samples from radiosensitive cancer patients for expression defects in major DSB proteins such as LIG4. LIG4 and RCC4 proteins showed reduced expression in addition to a corresponding reduction in both gene products at the mRNA level. The impact of LIG4 on RR may be due to the following reported molecular mechanisms. The activity of LIG4 is regulated by other proteins, such as XRCC4, which is the key contributor to the stabilization of LIG4311. In addition, DNA-binding protein-1 negatively regulates DNA repair processes by downregulating the expression of LIG4312. Indeed, a LIG4 peptide was shown to be a substrate of DNA-PK in vitro; a phosphorylation site for DNA-PKcs is present at Thr650 in human LIG4, and LIG stability is regulated by multiple factors, including negative regulation by DNA-PK 313.

Screening for inhibitors of LIG4 offers a chance for target-based drug discovery to design RR drugs. Tseng et al.314 conducted a screen of 5280 compounds and found that rabeprazole and U73122 could specifically block the adenylate transfer step and DNA rejoining to inhibit IR-induced DNA damage repair by targeting LIG4. SCR7, identified by Srivastava et al.315, blocks LIG4-mediated joining by interfering with its DNA binding. NU7026 affects the radiosensitivity of wild-type LIG4 mouse embryonic fibroblasts316. Although inhibitors of LIG4 are considered potential anticancer drugs, they are likely not effective in cancer cells with mutations, which may affect radiotherapy outcomes. Thus, in the future, more investigations regarding LIG4 functions in the IR-induced DDR need to be conducted.

Targeting PARP-1

PARP-1 is the most extensively studied nuclear enzyme of the PARP superfamily317. As reported previously, PARP-1 has been suggested to be a key regulator of DNA damage repair318. In the response to DNA damage, poly (ADP-ribosyl)ation (PARylation) of proteins is an initial reaction319. For instance, in the case of DNA damage, PARP-1 recognizes NAD+ as a major substrate320. PARylation of proteins post translation is suggested to provide a local signal of DNA damage because of the existence of poly(ADP-ribose)-binding domains, and DDR factors can regulate the functions of relevant proteins321. Furthermore, PARP-1 has been extensively studied, as it is a widely known regulator of DNA damage repair, particularly DSB repair 322.

Mechanistically, PARylation targets include nuclear DDR proteins, such as DNA-PKcs323 and PARP-1 itself. Since PARylated proteins can associate with negatively charged PAR, PARylated proteins can interact with DNA as well as regulate DNA damage as a signal324,325. Moreover, recent evidence has shown that PARP-1 has the potential for catalyzing the heterodimer formed with XPC-RAD23B and free PAR, suggesting the critical role of PARP-1 in IR-induced DNA damage 319.

Based on research indicating that inhibition of PARP-1 might sensitize cancer cells to radiotherapy326,327, the function of PARP-1 in DNA repair has been utilized in targeted radiotherapy. Currently, targeted radionuclide therapy with PARP-1 is a novel approach for cancer therapy328. Jannetti et al.329 reported that 131I-labeled PARP-1 therapy showed high potential for treating mice with glioblastoma, as the mice showed significantly longer survival than mice that received control vehicle in a subcutaneous model. Inhibitors of PARP-1 have also been developed to enhance the sensitivity of cancer cells to radiotherapy. The first identified inhibitor was nicotinamide, ~30 years ago330. After that, several generations of PARP-1 inhibitors were identified. Many of these inhibitors have been shown to enhance the anticancer efficacy of DNA-damaging agents such as IR331,332. For inhibitors of PARP (PARPi), their structures are similar to nicotinamide. PARPi mainly perform the following two functions. One is to inhibit PARP-1 catalytic activity, and the other is restrict PARP-1. The aims are typically to either inhibit PARylation or suppress PARP-1 release333,334. However, some older PARP-1 inhibitors showed limitations, such as nonselectivity and nonspecificity, in clinical radiotherapy331. Recently, some more specific and effective novel inhibitors have been developed. Ryu et al.335 suggested that the PARP-1 inhibitor KJ-28d might enhance the sensitivity of NSCLC to radiotherapy. Olaparib was the first PARP inhibitor approved (in December 2014) for cancer therapy by the FDA (https://www.astrazeneca.com/media-center/press-releases/2014/lynparza-approved-us-fda-brca-mutated-ovarian-cancer-treatment-19122014.html#) and by the European Union (https://www.astrazeneca.com/media-center/press-releases/2014/lynparza-approved-european-union-brca-mutated-ovarian-cancer-treatment-18122014.html#). It was approved for use in patients with advanced ovarian cancer and BRCA mutations. In January 2016, the US FDA further granted the Breakthrough Therapy Designation to olaparib for treating patients with metastatic-castration-resistant prostate cancer carrying BRCA1/2 or ATM mutations (https://www.astrazeneca.com/media-center/press-releases/2016/Lynparza-Olaparib-granted-Breakthrough-Therapy-Designation-by-US-FDA-for-treatment-of-BRCA1-2-or-ATM-gene-mutated-metastatic-Castration-Resistant-Prostate-Cancer-28012016.html#). Generally, cancer cells lacking either of the tumor suppressors BRCA1 and BRCA2, which are key components in the HR pathway of DSB repair, are selectively sensitive to PARP family inhibitors. Mechanistically, SSBs are primarily repaired by PARP-1. However, when DNA damage is caused by PARPi, inhibiting PARP-1 may not be lethal because there are still other repair pathways that function in the DDR, such as HR. However, the absence of BRCA1/2 results in a deficiency of HR activity, and cytotoxicity is present because DNA lesions caused by PARPi cannot be repaired due to the lack of HR activation336. Bourton et al.337 demonstrated that compared to normal BRCA cells, BRCA1+/− lymphoblastoid cells treated with olaparib, followed by IR exhibited decreased BRCA1 protein levels and increased apoptosis, resulting in radiation hypersensitivity; these results suggest that the combination of a PARP-1 inhibitor with radiotherapy has clinical relevance in treating BRCA1-associated cancers. AZD2281 is also an effective radiosensitizer for carbon-ion radiotherapy, indicating that PARP-1 has a wide therapeutic range in combination with LET radiation by blocking the DNA damage repair response327. The PARP-1 inhibitor ABT-888 enhanced radiosensitizing effects in hepatocellular carcinoma338. In cell experiments, Mk-4827, a PARP-1/2 inhibitor, promoted lung and breast cancer cell sensitivity to radiation339. Some inhibitors have been implicated to improve therapy sensitivity or inhibit cancer recurrence in cancer patients in the clinic. For example, niraparib is used in patients with ovarian cancer340. Niraparib is also found to inhibit the DDR in cancer cells, leading to an initial sensitization of cancer cells to radiotherapy341. Collectively, although PARP-1 inhibitors have been identified and tested after clinical trials and their function in enhancing the response of cancers to IR has been documented, the underlying mechanisms of radiotherapy sensitization by these inhibitors remain to be fully elucidated 342.

Targeting HIF-1