This case series analyzes the differences in presentation of voice and laryngeal disorders in patients with fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, and/or chronic fatigue syndrome.

Key Points

Question

What is the prevalence of different voice and laryngeal disorders in patients with chronic pain syndromes (CPSs) such as fibromyalgia syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, and chronic fatigue syndrome?

Findings

In this case series of 4249 patients, 215 with CPS and 4034 without CPS, patients with CPS were more likely to present with functional voice disorders, such as muscle tension dysphonia, and were less likely to present with laryngeal or airway problems.

Meaning

The clinical manifestations of the 3 types of CPS evaluated in this study, fibromyalgia syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, and chronic fatigue syndrome, appear to be indistinguishable from each other in their voice and airway presentation, which suggests that these disorders may be different clinical manifestations of a shared pathophysiology.

Abstract

Importance

Fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) are traditionally considered as distinct entities grouped under chronic pain syndrome (CPS) of an unknown origin. However, these 3 disorders may exist on a spectrum with a shared pathophysiology.

Objective

To investigate whether the clinical presentation of FMS, IBS, and CFS is similar in a population presenting with voice and laryngeal disorders.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This case series was a retrospective review of the medical records and clinical notes of patients treated between January 1, 2016, and December 31, 2017, at the Johns Hopkins Voice Center in Baltimore, Maryland. Patients with at least 1 CPS of interest (FMS, IBS, or CFS) were included (n = 215), along with patients without such diagnoses (n = 4034). Diagnoses, demographic, and comorbidity data were reviewed. Diagnoses related to voice and laryngeal disorders were subdivided into 5 main categories (laryngeal pathology, functional voice disorders, airway problems, swallowing problems, and other diagnoses).

Main Outcomes and Measures

Prevalence and odds ratios of 45 voice and laryngeal disorders were reviewed. Odds ratios (ORs) were calculated by comparing patients with CPS with control patients.

Results

In total, 4249 individuals were identified; 215 (5.1%) had at least 1 CPS and 4034 (94.9%) were control participants. Patients with CPS were 3 times more likely to be women compared with the control group (173 of 215 [80.5%] vs 2318 of 4034 [57.5%]; OR, 3.156; 95% CI, 2.392-4.296), and the CPS group had a mean (SD) age of 57.80 (15.30) years compared with the mean (SD) age of 55.77 (16.97) years for the control group. Patients with CPS were more likely to present with functional voice disorders (OR, 1.812; 95% CI, 1.396-2.353) and less likely to present with laryngeal pathology (OR, 0.774; 95% CI, 0.610-0.982) or airway problems (OR, 0.474; 95% CI, 0.285-0.789).

Conclusions and Relevance

The voice and airway presentation of patients with FMS, IBS, and/or CFS appears to be indistinguishable from each other. This finding suggests that these 3 diseases share upper airway symptoms.

Introduction

Medically unexplained symptoms are a classification commonly encountered in clinical medicine but are not yet known to have an organic origin.1,2 Medically unexplained symptoms occur in chronic symptom complexes, which are grouped into different diagnoses such as fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS). As a group and individually, these 3 diseases are common, with an estimated prevalence ranging from 230 to 20 000 per 100 000 persons worldwide.3,4,5,6 Ascertaining the number of patients with medically unexplained symptoms is challenging because of physicians’ lack of awareness and the reluctance of most patients with these conditions to seek help in the health care system or receive medical treatment.7,8,9 Because all of these diseases are defined by their physical symptoms, given that no testing is performed to confirm an underlying organic disease,10 they are a cost burden to the health care system; these conditions can be diagnosed only by definitively excluding the organic disease.11 Furthermore, it is uncertain whether treatment itself is effective.9,12

Commonly encountered chronic pain syndromes (CPSs), such as FMS, IBS, and CFS, are traditionally considered as distinct entities. However, they may exist on a spectrum with a shared pathophysiology, and all of them may be grouped under CPS spectrum disorders.10 Supporting this hypothesis is that these disorders share a set of multiple symptoms, coexisting psychiatric diagnoses such as anxiety or depressive disorders, and treatment involving antidepressants.13

Voice and airway symptoms are not part of the formal diagnostic criteria for FMS, IBS, and CFS, but our clinical observation is that patients with these 3 diseases are commonly encountered in clinical practice. Given the shared spectrum of disease among these medically unexplained symptoms, we hypothesized that the clinical manifestation of FMS, IBS, and CFS would be similar in a population presenting with voice and laryngeal disorders.

Methods

Patient Selection

We conducted a retrospective review of medical records of all patients treated at least once at the Johns Hopkins Voice Center in Baltimore, Maryland, between January 1, 2016, and December 31, 2017. This case series was approved by the institutional review board of The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, which waived the participant informed consent requirement because the study used deidentified data.

In total, 4249 individuals were identified, and all of these patients were treated by 1 of 3 designated laryngologists (S.R.B., A.T.H., and L.M.A.). Because we established no exclusion criteria, we reviewed the medical records of all patients treated at the center during the study period.

We identified 215 patients with at least 1 of the chronic pain syndromes (CPSs) of interest: FMS, IBS, and CFS. The remaining 4034 patients were classified as controls in the study design.

Variables Reviewed

Collected demographic data included age, sex, race/ethnicity, smoking status (never, former, or current), and all comorbidities documented in the medical records. All available medical reports and clinical notes for every patient during the qualifying period (January 1, 2016, to December 31, 2017) were reviewed, and diagnoses related to voice and laryngeal disorders were recorded. A list of the center’s 45 most commonly seen diagnoses within voice and laryngeal disorders was created before study start. All diagnoses were subdivided into 5 main categories: laryngeal pathology, functional voice disorders (FVD), airway problems, swallowing problems, and other. One to 4 diagnoses per patient were recorded. A summary of all diagnoses in each category is presented in the Box.

Box. 45 Voice and Laryngeal Disorder Diagnoses Subdivided Into 5 Categories.

Laryngeal Pathology

Vocal cord cancer

Chronic laryngitis

Phonotraumatic injury

Vocal cord granuloma

Vocal cord paralysis

Vocal cord paresis

Vocal cord cyst

Vocal cord leukoplakia

Vocal cord dysplasia

Presbyphonia

Fungal laryngitis

Laryngeal papilloma

Reinke edema

Inflammatory vocal cord lesion

Ulcerative laryngitis

Glottic webbing

Vocal cord scar or sulcus

Non–squamous cell carcinoma vocal cord cancer

Laryngocele

Spasmodic dysphonia

Dysarthria

Dystonia

Laryngeal tremor

Functional Voice Disorders

Muscle tension dysphonia

Dysphonia

Hoarseness

Hypophonia

Airway Problems

Supraglottic, glottic, or posterior glottic stenosis

Subglottic or tracheal stenosis

Tracheostomy

Tracheomalacia

Shortness of breath

Paradoxical vocal cord motion

Swallowing Problems

Laryngopharyngeal reflux disease

Dysphagia

Cricopharyngeal hypertrophy

Aspiration

Esophageal stricture

Esophageal perforation

Esophageal dysmotility

Zenker diverticulum

Eosinophilic esophagitis

Other Diagnoses

Long-term cough

Sinonasal complaints

History of head and neck cancer

At The Johns Hopkins Hospital, the electronic medical record software used is called Epic (Epic Systems Corp). One of us (K.P.) searched Epic for the following International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification, codes: M79.7 (FMS), K58 (IBS), and G89.4 (CPS). Clinical notes were also searched for the following terms: irritable bowel syndrome, IBS, fibromyalgia, FM, chronic fatigue syndrome, and CFS. This term search was performed to identify patients whose diagnosis was not listed in Epic but was documented in clinical notes because the diagnosis could have come from an outside clinician.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive categorical variables were presented as numbers (and percentages). Multivariate logistic regression models adjusted for age and sex were created. Univariate analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism, version 6.01 (GraphPad Software), and multivariate logistic regression modeling was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 25 (IBM Corp). Data were analyzed from September 2019 to December 2019.

Results

Patient Demographics

The medical records of 4249 patients treated at the Johns Hopkins Voice Center were analyzed. A total of 215 patients (5.1%) had at least 1 CPS, including 77 with FMS (35.8%; 1.8% of the center’s population), 80 with IBS (37.2%; 1.9% of the center’s population), and 70 with CFS (32.6%; 1.7% of the center’s population). Five patients had both CFS and IBS diagnoses, whereas 7 patients had both IBS and FMS. The remaining patients were classified as controls (n = 4034 [94.9%]). The demographic data of patients with CPS were compared with those of control patients and presented in Table 1. Patients with CPS were 3 times more likely to be women compared with the control group (173 of 215 [80.5%] vs 2318 of 4034 [57.5%]; odds ratio [OR], 3.156; 95% CI, 2.392-4.296) (Table 1) and had a mean (SD) age of 57.80 (15.30) years, compared with the mean (SD) age of 55.77 (16.97) years for the control group. No statistically significant differences in age, race/ethnicity, and smoking status were found between the 2 groups.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics and Smoking Status of Patients With at Least 1 Chronic Pain Syndrome vs Control Patients .

| Variable | No. (%) | OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CPS group (n = 215) | Control group (n = 4034) | ||

| Age, y | NA | ||

| <50 | 63 (29.3) | 1321 (32.7) | |

| ≥50 | 152 (70.7) | 2713 (67.3) | |

| Sex | |||

| Women | 173 (80.5) | 2318 (57.5) | 3.156 (2.392-4.296) |

| Men | 42 (19.5) | 1716 (42.5) | 1 [Reference] |

| Race/ethnicity | NA | ||

| White | 144 (67.0) | 2542 (63.0) | |

| Black | 56 (26.0) | 1046 (25.9) | |

| Other | 15 (7.0) | 446 (11.1) | |

| Smoking status | NA | ||

| Never | 138 (64.2) | 2461 (61.0) | |

| Former | 64 (29.8) | 1178 (29.2) | |

| Current | 13 (6.0) | 350 (8.7) | |

| No information | NA | 45 (1.1) | |

Abbreviations: CPS, chronic pain syndrome; NA, not applicable; OR, odds ratio.

Laryngeal Manifestations and Pathology in CPS

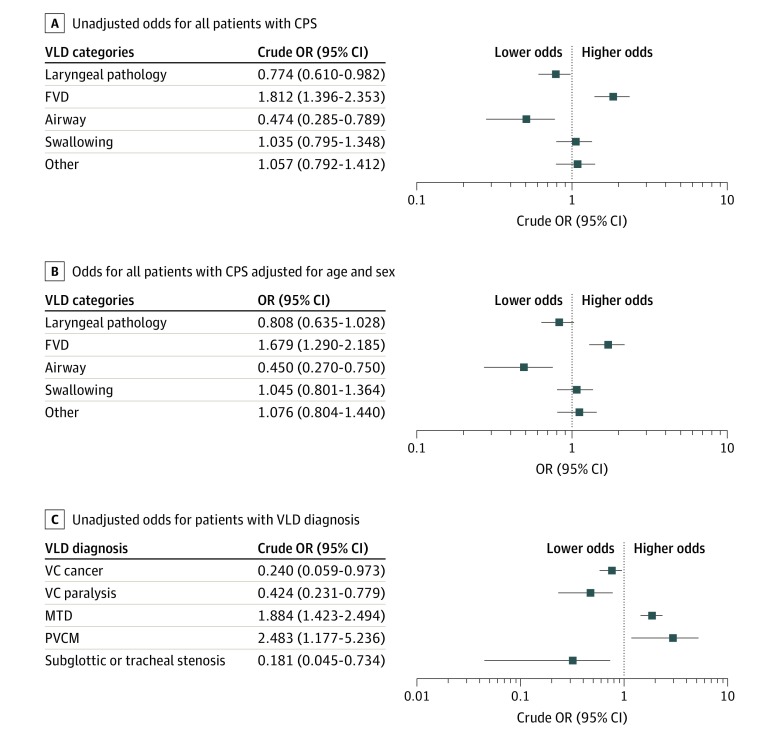

Patients with at least 1 CPS presented more often with FVD compared with those in the control group (OR, 1.812; 95% CI, 1.396-2.353) (Figure 1A). This association persisted when adjusted for age and sex in the multivariate model (adjusted OR, 1.679; 95 CI%, 1.290-2.185) (Figure 1B). Laryngeal pathology (103 [30.9%] vs 2241 [36.7%]) and airway problems (16 [4.8%] vs 588 [9.6%]) occurred but were significantly underrepresented in the CPS group compared with the control group. Patients with CPS had decreased odds for laryngeal pathology (OR, 0.774; 95% CI, 0.610-0.982) and airway problems (OR, 0.474; 95% CI, 0.285-0.789) (Figure 1A). When adjusted for age and sex, the association persisted for airway problems (OR, 0.450; 95% CI, 0.270-0.750) (Figure 1B). The frequency of swallowing problems (75 [22.8%] vs 1336 [22.1%]) and other diagnoses (55 [16.7%] vs 969 [16.0%]) did not differ significantly between patients with CPS and individuals in the control group. Complete results for every single diagnosis are presented in eTable 1 in the Supplement. The summary of significant results is presented in Table 2 and Figure 1A-C.

Figure 1. Odds of Voice and Laryngeal Disorders (VLDs) in Patients With Chronic Pain Syndrome (CPS) vs Control Patients.

Error bars indicate 95% CIs; FVD, functional voice disorders; MTD, muscle tension dysphonia; OR, odds ratio; PVCM, paradoxical vocal cord motion; VC, vocal cord.

Table 2. Summary of Other Diagnoses for Patients With CPS.

| Diagnosis | No. (%) | OR (95% CI)a | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPS group (n = 215) | Control group (n = 4034) | Unadjusted | Adjustedb | |

| Laryngeal pathology | 103 (30.9)c | 2241 (36.7) | 0.774 (0.610-0.982) | 0.808 (0.635-1.028) |

| Vocal cord | ||||

| Cancer | 2 (0.9)d | 150 (3.7) | 0.240 (0.059-0.973) | 0.330 (0.081-1.348) |

| Paralysis | 11 (5.1) | 456 (11.3) | 0.424 (0.231-0.779) | 0.407 (0.221-0.751) |

| Functional voice disorder | 80 (24.0) | 908 (14.9) | 1.812 (1.396-2.353) | 1.679 (1.290-2.185) |

| Muscle tension dysphonia | 66 (30.7) | 709 (17.6) | 1.884 (1.423-2.494) | 1.748 (1.317-2.320) |

| Airway problems | 16 (4.8) | 588 (9.6) | 0.474 (0.285-0.789) | 0.450 (0.270-0.750) |

| Supraglottic, glottic, or posterior glottic stenosis | NA | 109 (2.7) | NA | NA |

| Subglottic or tracheal stenosis | 2 (0.9) | 196 (4.9) | 0.181 (0.045-0.734) | 0.163 (0.040-0.659) |

| Paradoxical vocal cord motion | 8 (3.7) | 60 (1.5) | 2.483 (1.177-5.236) | 2.364 (1.110-5.032) |

| Swallowing problems | 75 (22.8) | 1336 (22.1) | 1.035 (0.795-1.348) | 1.045 (0.801-1.364) |

| Other diagnoses | 55 (16.7) | 969 (16.0) | 1.057 (0.792-1.412) | 1.076 (0.804-1.440) |

Abbreviations: CPS, chronic pain syndrome; NA, not applicable.

Odds of voice and laryngeal disorders in patients with CPS vs control patients.

Adjusted for age and sex.

Percentage of all diagnoses in the group.

Percentage of patients in the group with the diagnosis.

Examined by specific diagnoses, objective laryngeal pathology was underrepresented in the CPS group. Patients with CPS had lower odds for vocal cord cancer (OR, 0.240; 95% CI, 0.059-0.973) and vocal cord paralysis or immobility (OR, 0.424; 95 CI%, 0.231-0.779) compared with control individuals (Figure 1C). In the multivariate model, when adjusted for age and sex, the association persisted only for vocal cord paralysis or immobility (OR, 0.407; 95% CI, 0.221-0.751) (Table 2).

Functional Voice Disorders in CPS

In the CPS group, FVD diagnoses represented 24.0% (n = 80) of all diagnoses recorded for the group, compared with 14.9% (n = 908) in control patients. Muscle tension dysphonia (OR, 1.884; 95% CI, 1.423-2.494) (Figure 1C) was overrepresented in patients with CPS (n = 66 [30.7%]) compared with control patients (n = 709 [17.6%]). The association persisted when adjusted for age and sex (adjusted OR, 1.748; 95% CI, 1.317-2.320) (Table 2).

Airway Problems in CPS

Airway problems constituted 4.8% (n = 16) of all the voice and laryngeal disorder diagnoses in the CPS group, compared with 9.6% (n = 588) in the control group. Patients with CPS had decreased odds for airway stenoses (OR, 0.474; 95% CI, 0.285-0.789). In the multivariate model, the odds for presenting with subglottic stenosis were lower compared with the odds for the control group (adjusted OR, 0.163; 95% CI, 0.040-0.659) (Table 2). Those patients also had increased odds for paradoxical vocal cord motion (OR, 2.483; 95% CI, 1.177-5.236) (Figure 1C).

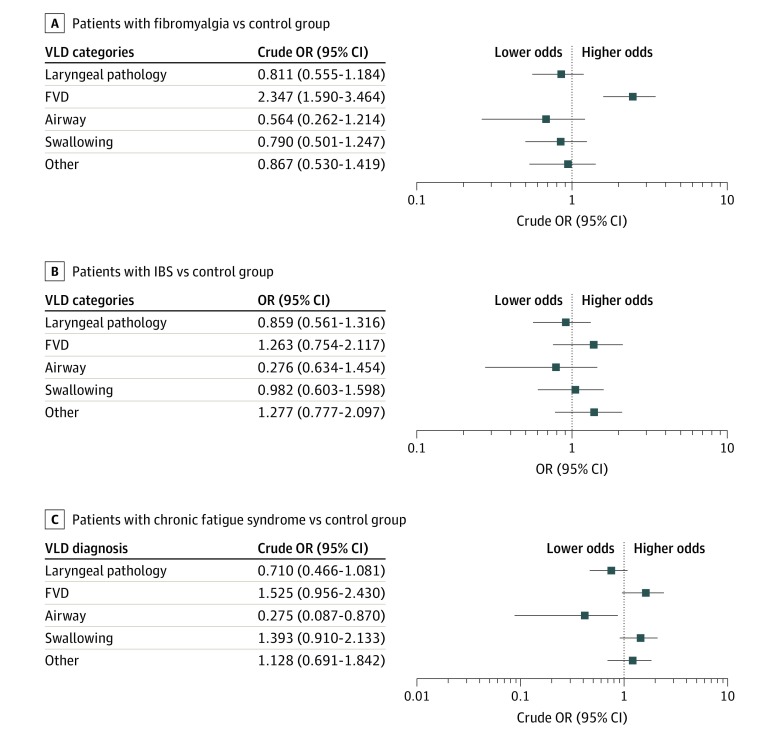

Laryngeal Manifestations in FMS, IBS, and CFS

Seventy-seven of 215 patients with CPS (35.8%) had FMS (eTable 2 in the Supplement). The CPS group had statistically significantly increased odds for presenting with FVD (OR, 2.347; 95% CI, 1.590-3.464) (Figure 2A). The association persisted when adjusted for age and sex (adjusted OR, 2.131; 95% CI, 1.440-3.153) (eTable 2 in the Supplement). When analyzed by individual diagnoses, patients with FMS had more than 2-fold increased odds for muscle tension dysphonia (OR, 2.338; 95% CI, 1.541-3.548) and paradoxical vocal cord motion (OR, 3.204; 95% CI, 1.149-8.939) compared with control participants. The odds for airway problems (OR, 0.564; 95% CI, 0.262-1.214) and vocal cords paralysis (OR, 0.308; 95% CI, 0.098-0.971) were found to be lower in patients with FMS (Figure 2A and eTable 2 in the Supplement). A summary of results for FMS is presented in eTable 2 in the Supplement).

Figure 2. Odds of Voice and Laryngeal Disorders (VLDs) in Patients With Fibromyalgia, Irritable Bowel Syndrome, or Chronic Pain Syndrome vs Control Group.

Error bars indicate 95% CIs; FVD, functional voice disorders; and OR, odds ratio.

Eighty of 215 patients with CPS (37.2%) had IBS. These patients had increased odds for presenting with FVD (OR, 1.263; 95% CI, 0.754-2.117) (Figure 2B; eTable 3 in the Supplement). When analyzed by single diagnoses, patients with IBS had more than 4-fold increased odds for paradoxical vocal cord motion (OR, 4.223; 95% CI, 1.507-11.837) compared with control patients (eTable 3 in the Supplement). The odds for airway problems (OR, 0.634; 95% CI, 0.276-1.454) were found to be lower in patients with IBS (eTable 3 in the Supplement). A summary of significant results for IBS is presented in eTable 3 in the Supplement.

Seventy of 215 patients with CPS (32.6%) had CFS. Patients in this group had increased odds for presenting with FVD (OR, 1.525; 95% CI, 0.956-2.430) (Figure 2C). The odds for airway problems were also found to be lower in patients with CFS (OR, 0.275; 95% CI, 0.087-0.870) (Figure 2C). A summary of significant results for CFS is presented in eTable 4 in the Supplement.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this case series is the first study to comprehensively describe voice and laryngeal concerns in patients with some of the most common medically unexplained symptoms, such as IBS, FMS, and CFS. Compared with a large control population, patients with CPS received FVD diagnosis at a significantly higher rate but had a lower rate of objective clinical findings.

Because of their complex symptoms, IBS, FMS, and CFS are common diagnoses and commonly encountered in clinical practice. The prevalence of IBS was reported to be in the range of 10% to 20% and estimated to be 7.1% in North America.3 Worldwide, criteria-meeting FMS was diagnosed in approximately 2% of the general population, 4% of women, and 15.2% of those with an IBS diagnosis.4 Chronic fatigue syndrome was less frequently diagnosed in the US general population, ranging from 0.23% and 0.42%.5,6 In the patient population of the Johns Hopkins Voice Center, the prevalence of these 3 syndromes were similar: 1.9% for IBS, 1.8% for FMS, and 1.7% for CFS. Thus, the prevalence of IBS at the center was substantially lower than the population estimates in North America, and the prevalence of CFS among patients at the center was higher than that in the US population. In this study, the case population was characterized by a predominance of women, with a female to male ratio of 4:1. The odds were 3-fold higher for a patient with CPS to be female compared with the control population. This finding was anticipated because female sex is one of the most predominant risk factors for CPS.14,15

The prevalence of voice and laryngeal disorders in the general adult population in Korea was estimated to be 7.6%.16 Commonly diagnosed voice disorders are classified into 2 distinct groups: organic voice disorders and FVD, which can further be divided into psychogenic voice disorders, primary muscle tension voice disorders, or secondary muscle tension voice disorders.17 Among patients with FVD, female predominance (female to male ratio of 3:1) was found.18 The many known risk factors for FVD include stressful life events as well as disorders of negative-emotions expression such as anxiety, interpersonal sensitivity, or distrust toward others.19,20,21,22,23,24,25 Based on findings of the present study, we can add medically unexplained symptoms such as IBS, FMS, and CFS to the list of precipitants and risk factors of FVD development. In the study sample, a substantial percentage (30.7%) of patients with CPS presented with muscle tension dysphonia, which was common among all of the individual diseases under medically unexplained symptoms but was different in the control population. The overrepresentation of FVD and the relatively lower rates of objective findings on laryngoscopy shared among IBS, FMS, and CFS support the theory that these 3 diseases may be different manifestations of a shared pathophysiology.

Patients with CPS make up a substantial fraction of all patients treated in voice clinics (at least 5%, as in our sample). These patients have complex conditions, often with many related symptoms, that could be viewed as refractory to treatment given the low rates of cure for the underlying disease.26 For these patients, the effectiveness of voice treatment and voice therapy likely depends on the cooperation of neurologists and psychiatrists who are treating the neurological and psychological symptoms of these chronic diseases. Otolaryngologists should be aware of the treatment options for patients with CPS and should consider involving multiple medical specialties in FVD management, such as speech-language pathology and physical therapy. We believe that the next important step is to investigate whether the recommended treatment of FVD is effective in this unique group of patients.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, it was retrospective. Second, the prevalence of CPS in the center’s population differed substantially from and may not be representative of the general population with medically unexplained symptoms. In this study, eligible patients were identified solely on the basis of their available medical records. However, medical records and documentation are not always reliable and do not always include all medical comorbidities. In addition, patients with CPS often do not share their diagnosis or seek treatment,27 which makes it highly possible that this study’s control group included at least some patients with CPS. However, we believe that accurately identifying those patients and moving them into the CPS group would strengthen the statistical value of the study’s findings.

Conclusions

The clinical manifestations of FMS, IBS, and CFS seem to be indistinguishable from each other, judging by the patient’s voice and airway presentation. Patients with these syndromes may be more likely to present with subjective FVD and less likely to present with objective clinical findings such as laryngeal pathology and airway problems. This study showed that these 3 diseases may have shared upper airway symptoms and are commonly encountered in clinical practice.

eTable 1. Odds of Voice Laryngeal Disorders in Patients With Chronic Syndromes vs Control Group

eTable 2. Odds of Voice Laryngeal Disorders in Patients With Fibromyalgia vs Control Group

eTable 3. Odds of Voice Laryngeal Disorders in Patients With IBS vs Control Group

eTable 4. Odds of Voice Laryngeal Disorders in Patients With Chronic Fatigue Syndrome vs Control Group

References

- 1.Dehoust MC, Schulz H, Härter M, et al. Prevalence and correlates of somatoform disorders in the elderly: results of a European study. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2017;26(1):e1550. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katon W, Russo J. Somatic symptoms and depression. J Fam Pract. 1989;29(1):65-69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sperber AD, Dumitrascu D, Fukudo S, et al. The global prevalence of IBS in adults remains elusive due to the heterogeneity of studies: a Rome Foundation working team literature review. Gut. 2017;66(6):1075-1082. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-311240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heidari F, Afshari M, Moosazadeh M. Prevalence of fibromyalgia in general population and patients, a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatol Int. 2017;37(9):1527-1539. doi: 10.1007/s00296-017-3725-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jason LA, Richman JA, Rademaker AW, et al. A community-based study of chronic fatigue syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(18):2129-2137. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.18.2129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reyes M, Nisenbaum R, Hoaglin DC, et al. Prevalence and incidence of chronic fatigue syndrome in Wichita, Kansas. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(13):1530-1536. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.13.1530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bass C, Murphy M. Somatisation disorder in a British teaching hospital. Br J Clin Pract. 1991;45(4):237-244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rasmussen NH, Avant RF. Somatization disorder in family practice. Am Fam Physician. 1989;40(2):206-214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith RC, Lein C, Collins C, et al. Treating patients with medically unexplained symptoms in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(6):478-489. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20815.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lipowski ZJ. Somatization: the concept and its clinical application. Am J Psychiatry. 1988;145(11):1358-1368. doi: 10.1176/ajp.145.11.1358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Gucht V, Fischler B. Somatization: a critical review of conceptual and methodological issues. Psychosomatics. 2002;43(1):1-9. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.43.1.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith RC, Lyles JS, Gardiner JC, et al. Primary care clinicians treat patients with medically unexplained symptoms: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(7):671-677. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00460.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumano H, Kaiya H, Yoshiuchi K, Yamanaka G, Sasaki T, Kuboki T. Comorbidity of irritable bowel syndrome, panic disorder, and agoraphobia in a Japanese representative sample. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(2):370-376. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04048.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holley AL, Wilson AC, Palermo TM. Predictors of the transition from acute to persistent musculoskeletal pain in children and adolescents: a prospective study. Pain. 2017;158(5):794-801. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Byeon H. Prevalence of perceived dysphonia and its correlation with the prevalence of clinically diagnosed laryngeal disorders: the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys 2010-2012. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2015;124(10):770-776. doi: 10.1177/0003489415583684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sapienza C, Ruddy B. Voice Disorders. Plural Publishing; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morente J, Izquierdo A. Transtornos de la voz: Del Diagnóstico al Tratamiento. Ediciones Aljibe; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mirza N, Ruiz C, Baum ED, Staab JP. The prevalence of major psychiatric pathologies in patients with voice disorders. Ear Nose Throat J. 2003;82(10):808-810, 812, 814. doi: 10.1177/014556130308201015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lauriello M, Cozza K, Rossi A, Di Rienzo L, Coen Tirelli G. Psychological profile of dysfunctional dysphonia. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2003;23(6):467-473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baker J, Ben-Tovim DI, Butcher A, Esterman A, McLaughlin K. Development of a modified diagnostic classification system for voice disorders with inter-rater reliability study. Logoped Phoniatr Vocol. 2007;32(3):99-112. doi: 10.1080/14015430701431192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baker J, Ben-Tovim D, Butcher A, Esterman A, McLaughlin K. Psychosocial risk factors which may differentiate between women with functional voice disorder, organic voice disorder and a control group. Int J Speech Lang Pathol. 2013;15(6):547-563. doi: 10.3109/17549507.2012.721397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aronson AE, Peterson HW Jr, Litin EM. Psychiatric symptomatology in functional dysphonia and aphonia. J Speech Hear Disord. 1966;31(2):115-127. doi: 10.1044/jshd.3102.115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kinzl J, Biebl W, Rauchegger H. Functional aphonia: psychosomatic aspects of diagnosis and therapy. Folia Phoniatr (Basel). 1988;40(3):131-137. doi: 10.1159/000265900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roy N. Assessment and treatment of musculoskeletal tension in hyperfunctional voice disorders. Int J Speech Lang Pathol. 2008;10(4):195-209. doi: 10.1080/17549500701885577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stone L. Blame, shame and hopelessness: medically unexplained symptoms and the ‘heartsink’ experience. Aust Fam Physician. 2014;43(4):191-195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Verbrugge LM, Ascione FJ. Exploring the iceberg. Common symptoms and how people care for them. Med Care. 1987;25(6):539-569. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198706000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Odds of Voice Laryngeal Disorders in Patients With Chronic Syndromes vs Control Group

eTable 2. Odds of Voice Laryngeal Disorders in Patients With Fibromyalgia vs Control Group

eTable 3. Odds of Voice Laryngeal Disorders in Patients With IBS vs Control Group

eTable 4. Odds of Voice Laryngeal Disorders in Patients With Chronic Fatigue Syndrome vs Control Group