Key Points

Question

Are the risks of developing depression, anxiety, dementia, and Parkinson disease associated with burning mouth syndrome?

Findings

In this cohort study of 1758 individuals with and without burning mouth syndrome, the overall incidence of depression and anxiety during the follow-up period was higher in patients with burning mouth syndrome than in individuals without burning mouth syndrome. However, burning mouth syndrome was not significantly associated with increases in the rates of dementia or Parkinson disease among patients with the syndrome.

Meaning

This study found that burning mouth syndrome was associated with increases in the incidence of depression and anxiety among patients with the syndrome; clinicians should be aware of this association and be prepared to make referrals to appropriate health care professionals.

Abstract

Importance

Burning mouth syndrome is a chronic oral pain disorder that is characterized by a generalized or localized burning sensation without the presence of any specific mucosal lesions. It remains unclear, however, whether burning mouth syndrome is associated with the development of psychoneurological conditions among patients with the syndrome.

Objective

To evaluate the risk of developing psychoneurological conditions, including depression, anxiety, dementia, and Parkinson disease, in patients with burning mouth syndrome.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This retrospective population-based cohort study was conducted using a nationwide representative cohort sample from the Korean National Health Insurance Service–National Sample Cohort, which consists of data from approximately 1 million patients in South Korea. The study included 586 patients with burning mouth syndrome (patient group) and 1172 individuals without burning mouth syndrome (comparison group). The patient group included all patients who received inpatient and outpatient care for an initial diagnosis of burning mouth syndrome between January 1, 2002, and December 31, 2012. The comparison group was selected (2 individuals without burning mouth syndrome for each patient with burning mouth syndrome) using propensity score matching for sex, age, location of residence, household income level, and comorbidities. Data were collected and analyzed from January 1, 2002, to December 31, 2013.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Death and the incidence of psychopathological diseases. Affective disorder events that occurred among participants during the follow-up period were investigated using survival analysis, a log-rank test, and Cox proportional hazards regression models to estimate the incidence rates, survival rates, and hazard ratios, respectively, of participants who developed psychoneurological conditions.

Results

Of 1758 total participants, 1086 (61.8%) were female; 701 participants (39.9%) were younger than 45 years, 667 (37.9%) were aged 45 to 64 years, and 390 (22.2%) were older than 64 years. The overall incidence of depression and anxiety was higher in patients with burning mouth syndrome (n = 586; 30.8 incidents and 44.2 incidents per 1000 person-years, respectively) than in individuals without burning mouth syndrome (n = 1172; 11.7 incidents and 19.0 incidents per 1000 person-years, respectively). The results also indicated a similar incidence of dementia and Parkinson disease between the patient group (6.5 incidents and 2.5 incidents per 1000 person-years, respectively) and the comparison group (4.9 incidents and 1.7 incidents per 1000 person-years, respectively). After adjusting for sociodemographic factors (age, location of residence, household income level, and comorbidities), the adjusted hazard ratios for the development of depression and anxiety among patients with burning mouth syndrome were 2.77 (95% CI, 2.22-3.45) and 2.42 (95% CI, 2.02-2.90), respectively. However, no association was found between burning mouth syndrome and the risk of developing dementia and Parkinson disease.

Conclusions and Relevance

Results of this observational study suggest that burning mouth syndrome is associated with increases in the incidence of depression and anxiety but not in the incidence of dementia and Parkinson disease among patients with the syndrome. Clinicians should be aware of this association and be prepared to make referrals to appropriate mental health care professionals.

This cohort study of individuals with and without burning mouth syndrome uses data from the Korean National Health Insurance Service to examine the association between burning mouth syndrome and the risk of developing psychoneurological conditions among patients with burning mouth syndrome.

Introduction

Burning mouth syndrome is an idiopathic chronic pain disorder characterized by a persistent burning sensation in clinically normal oral mucosa without blood chemistry abnormalities.1 Burning sensations usually present bilaterally and with fluctuating intensity,2 which eating and drinking may sometimes help to alleviate.3 Although the tip and anterior two-thirds of the tongue are most commonly involved, other regions of the oral mucosa, such as the lateral border of the tongue, lips, and palate, are often involved.4 Burning mouth syndrome occurs more often in women, especially in those who have experienced menopause, than men. The syndrome is rarely diagnosed in women younger than 30 years.5,6,7

Although the pathogenesis of burning mouth syndrome is not clearly understood, psychological conditions and neuropathy have been proposed as potential etiological factors. In the past several decades, the association between burning mouth syndrome and psychopathological conditions, such as depression and anxiety, has been examined. Various studies have reported an increased prevalence of psychiatric symptoms and/or psychological disorders in patients with burning mouth syndrome.8,9,10,11 In addition, several previous studies have reported that patients with burning mouth syndrome have peripheral nerve atrophy in the tongue epithelium12,13,14 and frequently experience abnormal gustatory sensations, such as dysgeusia and phantom tastes.15,16,17 Thus, neuropathic mechanisms are considered to be potential pathophysiological mechanisms in the development of burning mouth syndrome. Central neuropathic pain is also a frequent manifestation of neurodegenerative diseases,18,19,20,21,22 such as dementia and Parkinson disease (PD). However, the pathophysiological association between central neuropathic pain and neurodegenerative diseases is not clearly defined.

To date, the association between burning mouth syndrome and the development of psychoneurological conditions, including depression, anxiety, dementia, and PD, remains unclear. Therefore, given the lack of literature examining the direct association between burning mouth syndrome and psychoneurological conditions, we investigated the association between burning mouth syndrome and the risk of developing psychoneurological conditions, including depression, anxiety, dementia, and PD, among patients with burning mouth syndrome. We used a representative sample from the 1 025 340 adults included in the South Korean National Sample Cohort. This data set from a nationwide representative cohort allowed us to trace participants’ medical service use histories and provided an opportunity to examine the association between burning mouth syndrome and the risk of developing psychoneurological conditions while adjusting for clinical and demographic factors.

Methods

Korean National Health Insurance Service

South Korea has maintained a nationwide health insurance system since 1963. The Korean National Health Insurance Service (KNHIS) stores nearly all of the national health system data in large central databases. The KNHIS also determines all medical costs, including costs to beneficiaries, medical facilities, and the government. Almost all medical data, including diagnostic codes, procedures, prescription drugs, and personal information, are included in the KNHIS database. The database uses diagnostic codes from the Korean Standard Classification of Diseases, Sixth Revision (KCD-6),23 which is similar to the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM).24 No patient health care records are duplicated or omitted because all citizens of South Korea receive a unique identification number at birth.

The present study used a representative sample from the KNHIS–National Sample Cohort (KNHIS–NSC) database. Data collected were from January 1, 2002, to December 31, 2012. The database yielded 1 025 340 nationally representative and randomly selected individuals, accounting for an estimated 2.2% of the South Korean population of approximately 46 million people in 2002. Stratified random sampling was performed using 1476 strata; data were categorized by age (18 groups), sex (2 groups), and household income level (41 groups, including 40 health insurance beneficiaries and 1 medical aid beneficiary) among the South Korean population. The health insurance system in South Korea classifies beneficiaries according to income level; the medical aid category comprises lower-income beneficiaries, and the health insurance category comprises higher-income beneficiaries.

This study was approved by the institutional review board of Chuncheon Sacred Heart Hospital, Hallym University College of Medicine (Chuncheon, Republic of Korea). Written informed consent was waived because the study used data from a deidentified database.

Study Population

A nationwide representative cohort sample from the KNHIS-NSC database was used for all analyses. The patient group included all patients who received inpatient and outpatient care for an initial diagnosis of burning mouth syndrome (KCD-6 code K14.6) between January 1, 2002, and December 31, 2012. The comparison group was selected (2 individuals without burning mouth syndrome for each patient with burning mouth syndrome) using propensity score matching for sex, age, location of residence, household income level, and comorbidities. In addition, we selected individuals in the comparison group without replacement by using nearest neighbor matching of propensity scores, with the order applied from highest to lowest scores. We used KCD-6 codes to analyze comorbidities, including hypertension (KCD-6 code I10, corresponding with ICD-9-CM code 401 for essential hypertension), diabetes (KCD-6 code E10–E14, corresponding with ICD–9–CM code 250 for diabetes), and chronic renal failure (KCD-6 code N18, corresponding with ICD-9-CM code 585 for chronic kidney disease), which are all known risk factors for the development of burning mouth syndrome.

Individuals were excluded if they had a diagnosis of psychopathological disease before they received a diagnosis of burning mouth syndrome. Each patient was followed up until December 31, 2013, and diagnoses of depression, anxiety, dementia, and PD were recorded according to KCD-6 criteria (for depression, KCD-6 codes F31.3, F31.4, F31.5, F32, F33, F34.1, and F38.1; for anxiety, KCD-6 codes F40 and F41; for dementia, KCD-6 codes F00, F01, and F03; and for PD, KCD-6 code G20). A total of 586 eligible patients with burning mouth syndrome (patient group) and 1172 individuals without burning mouth syndrome (comparison group) were enrolled.

Outcome Variables

Study covariates included sex, age, location of residence, household income level, and comorbidities. The study population was divided into 3 age groups (<45 years, 45-64 years, and >64 years), 3 residential areas (Seoul, the largest metropolitan region in South Korea; other large cities in South Korea; and small cities and rural areas), and 3 income-level groups (≤30.0%, 30.1%–69.9%, and ≥70.0% of the group median household income). Death and the incidence of psychopathological diseases were used as the primary end points. Patients who did not experience psychopathological symptoms or who were alive until December 31, 2013, were censored after this point.

We matched the enrollment year of individuals in the comparison group with the diagnosis year of the respective patient. We compared the prevalence of psychopathological diseases among the patient and comparison groups based on the number of person-years at risk, which was defined as the duration between either the date of diagnosis of burning mouth syndrome (patient group) or the first date of the year (comparison group) and the individual’s respective end point. No significant difference was observed in the distribution of hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and chronic renal failure between the comparison and patient groups; thus, comorbidities were defined as a diagnosis of any of these conditions before the diagnosis of burning mouth syndrome.

Statistical Analyses

This study paired individuals in the patient group with individuals in the comparison group using several matching variables, including enrollment year, sex, age, location of residence, household income level, and comorbidities. The χ2 test was used to evaluate between-group differences in sex, age, location of residence, household income level, and comorbidities. To calculate effect sizes, we used the Cramer V and Monte Carlo methods, which were applied to calculate 95% CIs for exact significance. When effect sizes were below the reference values (small effect size of 0.10 with 1 degree of freedom and 0.07 with 2 degrees of freedom), between-group differences that were found using the χ2 test were considered to be nonsignificant. Results were expressed as frequency (percentage). After performing preliminary analyses, we used Cox proportional hazards regression models to estimate the hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs for psychopathological outcomes after adjusting for sex, age, location of residence, household income level, and comorbidities. Incidence rates per 1000 person-years for psychopathological diseases were obtained by dividing the number of patients with specific diseases by the number of person-years at risk.

To estimate the probability of psychopathological disease incidence and the cumulative incidences of depression, anxiety, dementia, and PD in the patient and comparison groups, we performed a survival analysis using the Kaplan-Meier method, with significance assessed through a log-rank test. Tests were 2-sided and unpaired. All statistical analyses were performed using R software, version 3.3.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Data were analyzed from January 1, 2002, to December 31, 2013.

Results

Of 1758 total participants, 1086 (61.8%) were female; 701 participants (39.9%) were younger than 45 years, 667 (37.9%) were aged 45 to 64 years, and 390 (22.2%) were older than 64 years. A total of 586 patients with burning mouth syndrome were assigned to the patient group, and 1172 individuals without burning mouth syndrome were assigned to the comparison group. We found that the distributions of sex, age, location of residence, household income level, and comorbidities were similar between the patient and comparison groups because these variables were used for sample matching, indicating that group matching was performed appropriately. Details about the study population and group characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of Study Participants.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Comparison group (n = 1172) | Patient group (n = 586) | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 446 (38.1) | 226 (38.6) |

| Female | 726 (61.9) | 360 (61.4) |

| Age, y | ||

| <45 | 477 (40.7) | 224 (38.2) |

| 45-64 | 435 (37.1) | 232 (39.6) |

| >64 | 260 (22.2) | 130 (22.2) |

| Location of residence | ||

| Seoul | 235 (20.1) | 112 (19.1) |

| Other large city | 245 (20.9) | 122 (20.8) |

| Small city or rural area | 692 (59.0) | 352 (60.1) |

| Household income (% of group median) | ||

| Low (≤30.0) | 255 (21.8) | 132 (22.5) |

| Middle (30.1–69.9) | 376 (32.1) | 184 (31.4) |

| High (≥70.0) | 541 (46.2) | 270 (46.1) |

| Hypertension | ||

| No | 582 (49.7) | 300 (51.2) |

| Yes | 590 (50.3) | 286 (48.8) |

| Diabetes type 2 | ||

| No | 788 (67.2) | 378 (64.5) |

| Yes | 384 (32.8) | 208 (35.5) |

| Chronic renal failure | ||

| No | 1157 (98.7) | 576 (98.3) |

| Yes | 15 (1.3) | 10 (1.7) |

The patient group had a total of 5717 person-years for depression, 5409 person-years for anxiety, 6768 person-years for dementia, and 6813 person-years for PD (Table 2). The comparison group had a total of 12 516 person-years for depression, 12 075 person-years for anxiety, 13 143 person-years for dementia, and 13 251 person-years for PD. In the patient group, the incidence rate of psychoneurological conditions per 1000 person-years was 30.8 for depression, 44.2 for anxiety, 6.5 for dementia, and 2.5 for PD. In the comparison group, the incidence rate of psychoneurological conditions per 1000 person-years was 11.7 for depression, 19.0 for anxiety, 4.9 for dementia, and 1.7 for PD.

Table 2. Incidence of Psychoneurological Disease.

| Variable | Participants, No. | Depression | Anxiety | Dementia | Parkinson disease | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total cases | Total person-years | Incidence ratea | Total cases | Total person-years | Incidence ratea | Total cases | Total person-years | Incidence ratea | Total cases | Total person-years | Incidence ratea | ||

| Group | |||||||||||||

| Comparison | 1172 | 147 | 12 516 | 11.7 | 230 | 12 075 | 19 | 64 | 13 143 | 4.9 | 23 | 13 251 | 1.7 |

| Patient | 586 | 176 | 5717 | 30.8 | 239 | 5409 | 44.2 | 44 | 6768 | 6.5 | 17 | 6813 | 2.5 |

| Sex | |||||||||||||

| Male | 672 | 68 | 7198 | 9.4 | 125 | 6930 | 18 | 26 | 7518 | 3.5 | 10 | 7545 | 1.3 |

| Female | 1086 | 255 | 11 036 | 23.1 | 344 | 10 553 | 32.6 | 82 | 12 392 | 6.6 | 30 | 12 520 | 2.4 |

| Age, y | |||||||||||||

| <45 | 701 | 61 | 7670 | 8 | 90 | 7542 | 11.9 | 2 | 8030 | 0.2 | 2 | 8038 | 0.2 |

| 45-64 | 667 | 151 | 6892 | 21.9 | 220 | 6526 | 33.7 | 29 | 7749 | 3.7 | 11 | 7775 | 1.4 |

| >64 | 390 | 111 | 3673 | 30.2 | 159 | 3415 | 46.6 | 77 | 4131 | 18.6 | 27 | 4251 | 6.4 |

| Location of residence | |||||||||||||

| Seoul | 347 | 64 | 3618 | 17.7 | 90 | 3513 | 25.6 | 24 | 3988 | 6 | 8 | 4019 | 2 |

| Other large city | 367 | 54 | 3827 | 14.1 | 95 | 3647 | 26.1 | 13 | 4141 | 3.1 | 6 | 4169 | 1.4 |

| Small city or rural area | 1044 | 205 | 10 789 | 19 | 284 | 10 323 | 27.5 | 71 | 11 781 | 6 | 26 | 11 877 | 2.2 |

| Household income (% of group median) | |||||||||||||

| Low (≤30.0) | 387 | 73 | 3987 | 18.3 | 112 | 3821 | 29.3 | 23 | 4373 | 5.3 | 11 | 4402 | 2.5 |

| Middle (30.1–69.9) | 560 | 102 | 5809 | 17.6 | 131 | 5709 | 22.9 | 24 | 6396 | 3.8 | 7 | 6434 | 1.1 |

| High (≥70.0) | 811 | 148 | 8439 | 17.5 | 226 | 7953 | 28.4 | 61 | 9142 | 6.7 | 22 | 9228 | 2.4 |

| Comorbidities | |||||||||||||

| No | 747 | 55 | 8141 | 6.8 | 93 | 7951 | 11.7 | 6 | 8447 | 0.7 | 5 | 8460 | 0.6 |

| Yes | 1011 | 268 | 10 093 | 26.6 | 376 | 9533 | 39.4 | 102 | 11 464 | 8.9 | 35 | 11 605 | 3 |

Number of new cases per 1000 person-years during follow-up period.

We also analyzed HRs for the development of depression, anxiety, dementia, and PD using univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression models (Table 3). After adjusting for sex, age, location of residence, household income level, and comorbidities, we found that burning mouth syndrome was significantly associated with the development of depression (adjusted HR [aHR], 2.77; 95% CI, 2.22-3.45) and anxiety (aHR, 2.42; 95% CI, 2.02-2.90). However, no significant association was observed between burning mouth syndrome and the development of dementia or PD. The aHRs were 1.28 times (95% CI, 0.87-1.88) higher for dementia and 1.35 times (95% CI, 0.72-2.54) higher for PD among patients with burning mouth syndrome compared with individuals without burning mouth syndrome.

Table 3. Hazard Ratios for Psychoneurological Disease.

| Variable | Hazard ratio (95% CI)a | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | Anxiety | Dementia | Parkinson disease | |||||

| Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | |

| Group | ||||||||

| Comparison | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Patient | 2.62 (2.11-3.27) | 2.77 (2.22-3.45) | 2.35 (1.96-2.82) | 2.42 (2.02-2.90) | 1.32 (0.90-1.94) | 1.28 (0.87-1.88) | 1.42 (0.76-2.66) | 1.35 (0.72-2.54) |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Female | 2.45 (1.87-3.20) | 2.13 (1.62-2.80) | 1.81 (1.47-2.22) | 1.47 (1.19-1.82) | 1.88 (1.21-2.92) | 1.09 (0.69-1.70) | 1.78 (0.87-3.63) | 1.05 (0.51-2.19) |

| Age, y | ||||||||

| <45 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 45-64 | 2.76 (2.05-3.71) | 1.45 (1.03-2.04) | 2.85 (2.23-3.65) | 1.72 (1.30-2.29) | 14.79 (3.53-61.97) | 8.30 (1.88-36.70) | 5.59 (1.24-25.24) | 4.64 (0.93-23.17) |

| >64 | 3.81 (2.79-5.21) | 1.68 (1.16-2.43) | 4.01 (3.09-5.19) | 2.13 (1.57-2.91) | 80.77 (19.84-328.82) | 39.12 (8.89-172.04) | 26.25 (6.24-110.41) | 19.50 (3.92-97.11) |

| Location of residence | ||||||||

| Seoul | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Other large city | 0.80 (0.55-1.14) | 0.83 (0.58-1.20) | 1.02 (0.76-1.36) | 1.10 (0.82-1.47) | 0.53 (0.27-1.04) | 0.71 (0.36-1.43) | 0.73 (0.25-2.12) | 1.02 (0.35-2.99) |

| Small city or rural area | 1.07 (0.81-1.42) | 1.05 (0.79-1.40) | 1.08 (0.85-1.37) | 1.04 (0.82-1.32) | 1.01 (0.64-1.61) | 0.99 (0.62-1.57) | 1.11 (0.50-2.45) | 1.10 (0.50-2.43) |

| Household income (% of group median) | ||||||||

| Low (≤30.0) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Middle (30.1–69.9) | 0.96 (0.71-1.30) | 1.25 (0.92-1.69) | 0.78 (0.60-1.00) | 0.92 (0.71-1.18) | 0.70 (0.40-1.25) | 1.09 (0.61-1.94) | 0.43 (0.17-1.11) | 0.60 (0.23-1.58) |

| High (≥70.0) | 0.96 (0.72-1.27) | 1.03 (0.78-1.37) | 0.97 (0.77-1.21) | 1.01 (0.81-1.27) | 1.27 (0.79-2.05) | 1.25 (0.77-2.02) | 0.95 (0.46-1.96) | 0.96 (0.46-1.98) |

| Comorbidities | ||||||||

| No | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 3.94 (2.94-5.26) | 2.87 (2.03-4.04) | 3.42 (2.73-4.29) | 2.27 (1.73-2.99) | 12.55 (5.51-28.59) | 2.87 (1.20-6.85) | 5.05 (1.98-12.90) | 1.36 (0.48-3.86) |

Sex, age, location of residence, household income level, and comorbidities were used for Cox proportional hazards regression analyses.

We also found that female patients and older patients were associated with a significantly higher likelihood of developing depression and anxiety. Among women, the aHR was 2.13 (95% CI, 1.62-2.80) for depression and 1.47 (95% CI, 1.19-1.82) for anxiety. Among adults older than 64 years, the aHR was 1.68 (95% CI, 1.16-2.43) for depression and 2.13 (95% CI, 1.57-2.91) for anxiety. Comorbidities were also significantly associated with the development of depression (aHR, 2.87; 95% CI, 2.03-4.04) and anxiety (aHR, 2.27; 95% CI, 1.73-2.99). However, no significant association was identified between any of the other factors analyzed and the development of depression or anxiety.

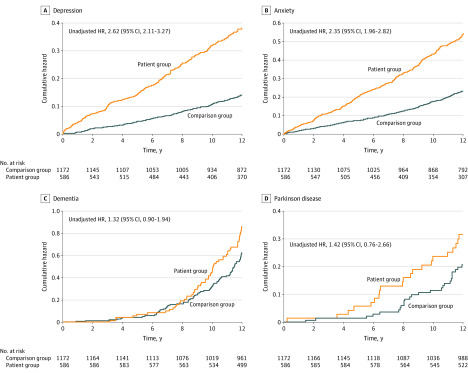

The reverse Kaplan-Meier survival curves and the results of log-rank tests are presented in the Figure, which depicts the cumulative incidences of depression, anxiety, dementia, and PD in the patient and comparison groups. The risk of depression and anxiety was significantly higher in the patient group (for depression, unadjusted HR, 2.62; 95% CI, 2.11-3.27; for anxiety, unadjusted HR, 2.35; 95% CI, 1.96-2.82) than in the comparison (reference) group. These log-rank tests indicated that patients with burning mouth syndrome developed depression and anxiety more frequently than individuals without burning mouth syndrome. No significant between-group difference was found in the risk of developing dementia (unadjusted HR, 1.32; 95% CI, 0.90-1.94) or PD (unadjusted HR, 1.42; 95% CI, 0.76-2.66).

Figure. Risk of Development of Psychoneurological Conditions Among Individuals With and Without Burning Mouth Syndrome.

HR indicates hazard ratio.

Discussion

Burning mouth syndrome is a chronic clinical condition that manifests as a burning sensation in the oral cavity without any accompanying abnormal clinical lesions or laboratory result indications. The International Association for the Study of Pain defines burning mouth syndrome as a painful condition characterized by an unremitting oral burning sensation in the absence of objective clinical changes in the oral mucosa. To our knowledge, the present study is the first to analyze the risk of developing psychoneurological conditions, such as depression, anxiety, dementia, and PD, in patients with burning mouth syndrome. We found that patients with burning mouth syndrome had a higher risk of developing depression and anxiety (aHR, 2.77; 95% CI, 2.22-3.45 for depression; aHR, 2.42; 95% CI, 2.02-2.90 for anxiety) than individuals without burning mouth syndrome, even after adjusting for patient sociodemographic characteristics and comorbidities. However, no association was found between burning mouth syndrome and the subsequent development of dementia or PD.

Some controversy remains regarding whether psychogenic pathological conditions occur primary or secondary to a diagnosis of burning mouth syndrome. In general, psychological disorders may be associated with the modulation of pain perception, increasing nerve transmission by peripheral pain receptors and altering individuals’ perceptions of pain.22,25,26,27 Given this association, psychosocial events may often be associated with the onset or exacerbation of symptoms in patients with burning mouth syndrome. Several previous studies have also reported that patients with burning mouth syndrome may be predisposed toward the development of depression and anxiety.28,29,30 In addition, 1 study of patients with burning mouth syndrome revealed that somatic conditions owing to unfavorable life experiences among patients with chronic pain may be associated with both personality and mood changes.31 Another study reported that patients with burning mouth syndrome, especially those with a comorbid phobia of oral cancer, may experience higher levels of pain, anxiety, and depression.32 Consistent with these studies, we found that a diagnosis of burning mouth syndrome was associated with an increase in the subsequent development of depression and anxiety. Log-rank test results further indicated that patients with burning mouth syndrome developed depressive and anxiety disorders more frequently than individuals without burning mouth syndrome.

Although the pathophysiological factors associated with burning mouth syndrome are not clearly understood, central and peripheral neuropathic mechanisms, such as the depletion of neuroprotective steroids and the denervation of the chorda tympani nerve fibers that innervate fungiform buds, are thought to be involved.26 In addition, 1 study revealed that patients with burning mouth syndrome exhibit particular brain responses owing to impaired central and peripheral nervous system function.33 Moreover, the use of topical clonazepam and capsaicin for the treatment of patients with burning mouth syndrome is supported based on known neuropathic mechanisms.27 One study reported that a diagnosis of burning mouth syndrome may be more common in patients with PD than in the general population34; however, in the present study, we did not find a significant association between a diagnosis of burning mouth syndrome and the subsequent development of dementia or PD. Thus, we could not assess whether the development of dementia and PD may be consequences of burning mouth syndrome or mechanisms in the onset of burning mouth syndrome.

Strengths and Limitations

Our study has several strengths. First, to our knowledge, this is the first nationwide retrospective cohort study evaluating the incidence of psychoneurological conditions in patients with burning mouth syndrome. In addition, numerous studies based on the KNHIS-NSC have been already published,35,36,37,38,39,40 which suggests that our analysis based on the KNHIS-NSC has good reliability. Second, to improve diagnostic accuracy, we included only patients with burning mouth syndrome that was diagnosed by otorhinolaryngologists and patients with anxiety disorder or depression that was diagnosed by psychiatrists. Third, 1 previous study that used data from the KNHIS–NSC reported a similar prevalence of 20 major diseases for each year; these findings imply that the KNHIS–NSC data are likely to have fair to good reliability.41

This study also has several limitations. First, we did not have access to patient health data on smoking or alcohol consumption. In addition, this study could not include substance use, underlying undiagnosed mental health issues, and other comorbidities associated with psychoneurological conditions. Therefore, we did not adjust for these potential confounding factors. Second, diagnoses of burning mouth syndrome were solely based on KCD diagnostic codes, which may be less accurate than diagnoses based on medical records data, as data often include medical history, physical examination results, and laboratory findings. Third, depression and anxiety include a wide variety of disease states that could not be distinguished given the somewhat simplistic diagnostic code system used here. Moreover, physicians may be more likely to recommend a psychiatric approach when treating patients with burning mouth syndrome; thus, the patient cohort could have been more likely to be identified as having mental health challenges compared with the comparison cohort. Fourth, we used the age data categories (<45 years, 45-64 years, and >64 years) that were specified in the KNHIS-NSC database; thus, we could not match the patient and comparison groups based on the actual age distribution of the participants in our study. For this reason, the study might have substantial residual bias within the categories.

Given this study’s retrospective cohort design, we were unable to directly examine or analyze the mechanisms underlying the association between burning mouth syndrome and depression or anxiety. Further studies are needed to confirm our findings and to explore the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms of depression and anxiety that may be associated with burning mouth syndrome.

Conclusions

The present study investigated a possible association between burning mouth syndrome and the development of psychoneurological conditions, including depression, anxiety, dementia, and PD. We found that patients with burning mouth syndrome had an increased risk of developing depression and anxiety. However, patients with burning mouth syndrome did not have a significantly increased risk of developing dementia or PD compared with individuals without burning mouth syndrome. We believe this study provides new and important insights into the association between burning mouth syndrome and psychiatric and neurological diseases. Clinicians should be aware of the potential comorbidities that may be present in patients with burning mouth syndrome and be prepared to make appropriate referrals to mental health professionals.

References

- 1.Sarantopoulos C. Burning mouth syndrome: a misunderstood, underinvestigated, and undertreated clinical challenge. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2013;38(5):378-379. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0b013e3182a3922b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spanemberg JC, Cherubini K, de Figueiredo MA, Yurgel LS, Salum FG. Aetiology and therapeutics of burning mouth syndrome: an update. Gerodontology. 2012;29(2):84-89. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2010.00384.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scala A, Checchi L, Montevecchi M, Marini I, Giamberardino MA. Update on burning mouth syndrome: overview and patient management. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2003;14(4):275-291. doi: 10.1177/154411130301400405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grushka M. Clinical features of burning mouth syndrome. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1987;63(1):30-36. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(87)90336-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergdahl M, Bergdahl J. Burning mouth syndrome: prevalence and associated factors. J Oral Pathol Med. 1999;28(8):350-354. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1999.tb02052.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gurvits GE, Tan A. Burning mouth syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(5):665-672. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i5.665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klasser GD, Epstein JB. Oral burning and burning mouth syndrome. J Am Dent Assoc. 2012;143(12):1317-1319. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2012.0093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rojo L, Silvestre FJ, Bagan JV, De Vicente T. Psychiatric morbidity in burning mouth syndrome. psychiatric interview versus depression and anxiety scales. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1993;75(3):308-311. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(93)90142-Q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Browning S, Hislop S, Scully C, Shirlaw P. The association between burning mouth syndrome and psychosocial disorders. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1987;64(2):171-174. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(87)90085-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Komiyama O, Obara R, Uchida T, et al. Pain intensity and psychosocial characteristics of patients with burning mouth syndrome and trigeminal neuralgia. J Oral Sci. 2012;54(4):321-327. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.54.321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klasser GD, Grushka M, Su N. Burning mouth syndrome. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2016;28(3):381-396. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2016.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lauria G, Majorana A, Borgna M, et al. Trigeminal small-fiber sensory neuropathy causes burning mouth syndrome. Pain. 2005;115(3):332-337. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.03.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yilmaz Z, Renton T, Yiangou Y, et al. Burning mouth syndrome as a trigeminal small fibre neuropathy: increased heat and capsaicin receptor TRPV1 in nerve fibres correlates with pain score. J Clin Neurosci. 2007;14(9):864-871. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2006.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beneng K, Yilmaz Z, Yiangou Y, McParland H, Anand P, Renton T. Sensory purinergic receptor P2X3 is elevated in burning mouth syndrome. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;39(8):815-819. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2010.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kolkka-Palomaa M, Jaaskelainen SK, Laine MA, Teerijoki-Oksa T, Sandell M, Forssell H. Pathophysiology of primary burning mouth syndrome with special focus on taste dysfunction: a review. Oral Dis. 2015;21(8):937-948. doi: 10.1111/odi.12345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hershkovich O, Nagler RM. Biochemical analysis of saliva and taste acuity evaluation in patients with burning mouth syndrome, xerostomia and/or gustatory disturbances. Arch Oral Biol. 2004;49(7):515-522. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2004.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim Y, Kim HI, Kho HS. Characteristics of men and premenopausal women with burning mouth symptoms: a case-control study. Headache. 2014;54(5):888-898. doi: 10.1111/head.12338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reichling DB, Levine JD. Pain and death: neurodegenerative disease mechanisms in the nociceptor. Ann Neurol. 2011;69(1):13-21. doi: 10.1002/ana.22351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Achterberg WP, Pieper MJ, van Dalen-Kok AH, et al. Pain management in patients with dementia. Clin Interv Aging. 2013;8:1471-1482. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S36739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cravello L, Di Santo S, Varrassi G, et al. Chronic pain in the elderly with cognitive decline: a narrative review. Pain Ther. 2019;8(1):53-65. doi: 10.1007/s40122-019-0111-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moreno CB, Hernandez-Beltran N, Munevar D, Gutierrez-Alvarez AM. Central neuropathic pain in Parkinson’s disease. Neurologia. 2012;27(8):500-503. doi: 10.1016/j.nrl.2011.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Komiyama O, Nishimura H, Makiyama Y, et al. Group cognitive-behavioral intervention for patients with burning mouth syndrome. J Oral Sci. 2013;55(1):17-22. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.55.17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Korea S. Korean Standard Classification of Diseases, Sixth Revision (KCD-6). Statistics Korea; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9). World Health Organization; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Minguez-Sanz MP, Salort-Llorca C, Silvestre-Donat FJ. Etiology of burning mouth syndrome: a review and update. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2011;16(2):e144-e148. doi: 10.4317/medoral.16.e144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Imamura Y, Shinozaki T, Okada-Ogawa A, et al. An updated review on pathophysiology and management of burning mouth syndrome with endocrinological, psychological and neuropathic perspectives. J Oral Rehabil. 2019;46(6):574-587. doi: 10.1111/joor.12795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coculescu EC, Tovaru S, Coculescu BI. Epidemiological and etiological aspects of burning mouth syndrome. J Med Life. 2014;7(3):305-309. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malik R, Goel S, Misra D, Panjwani S, Misra A. Assessment of anxiety and depression in patients with burning mouth syndrome: a clinical trial. J Midlife Health. 2012;3(1):36-39. doi: 10.4103/0976-7800.98816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van der Ploeg HM, van der Wal N, Eijkman MA, van der Waal I. Psychological aspects of patients with burning mouth syndrome. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1987;63(6):664-668. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(87)90366-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Galli F, Lodi G, Sardella A, Vegni E. Role of psychological factors in burning mouth syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cephalalgia. 2017;37(3):265-277. doi: 10.1177/0333102416646769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jerlang BB. Burning mouth syndrome (BMS) and the concept of alexithymia—a preliminary study. J Oral Pathol Med. 1997;26(6):249-253. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1997.tb01232.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsuoka H, Himachi M, Furukawa H, et al. Cognitive profile of patients with burning mouth syndrome in the Japanese population. Odontology. 2010;98(2):160-164. doi: 10.1007/s10266-010-0123-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shinozaki T, Imamura Y, Kohashi R, et al. Spatial and temporal brain responses to noxious heat thermal stimuli in burning mouth syndrome. J Dent Res. 2016;95(10):1138-1146. doi: 10.1177/0022034516653580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coon EA, Laughlin RS. Burning mouth syndrome in Parkinson’s disease: dopamine as cure or cause? J Headache Pain. 2012;13(3):255-257. doi: 10.1007/s10194-012-0421-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim JY, Hong JY, Kim DK. Association of sudden sensorineural hearing loss with risk of cardiocerebrovascular disease: a study using data from the Korea National Health Insurance Service. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;144(2):129-135. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2017.2569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim JY, Lee JW, Kim M, Kim MJ, Kim DK. Association of idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss with affective disorders. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;144(7):614-621. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2018.0658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim JY, Ko I, Kim MS, Yu MS, Cho BJ, Kim DK. Association of chronic rhinosinusitis with depression and anxiety in a nationwide insurance population. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;145(4):313-319. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2018.4103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim JY, Ko I, Kim MS, Kim DW, Cho BJ, Kim DK. Relationship of chronic rhinosinusitis with asthma, myocardial infarction, stroke, anxiety, and depression. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(2):721-727. . doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim JY, Ko I, Kim DK. Association of obstructive sleep apnea with the risk of affective disorders. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;145(11):1020-1026. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2019.2435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim JY, Ko I, Cho BJ, Kim DK. Association of obstructive sleep apnea with the risk of Meniere’s disease and sudden sensorineural hearing loss: a study using data from the Korean National Health Insurance Service. J Clin Sleep Med. 2019;15(9):1293-1301. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.7922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rim TH, Kim DW, Han JS, Chung EJ. Retinal vein occlusion and the risk of stroke development: a 9-year nationwide population-based study. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(6):1187-1194. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.01.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]