Abstract

This interrupted time series analysis evaluates the association of nudges with zoledronate prescription vs more expensive denosumab.

Identifying effective strategies to promote high-value, evidence-based prescribing is critical in oncology, where spending is projected to surpass $150 billion in 2020, driven in large part by cancer drugs.1 By intentionally modifying the way choices are framed, behavioral nudges can lead to desirable changes in prescribing while preserving clinician choice, and have been used effectively in primary care settings.2 It is unknown whether nudges can also influence specialty drug prescribing, where financial incentives often favor more expensive therapies.3

Zoledronate and denosumab are guideline-endorsed, evidence-based bone-modifying agents that reduce skeletal-related events in patients with bone metastases, but differ in annual cost dramatically ($215 for zoledronate vs $26 000 for denosumab).4,5 We implemented a series of increasingly potent6 clinician-targeted nudges to encourage zoledronate prescription as the higher-value alternative across a multisite academic health system in Pennsylvania and New Jersey. In this report, we evaluate the association of nudges with zoledronate prescription.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective controlled quasi-experimental study, taking advantage of concurrent quality improvement initiatives at 2 of 7 practice sites in the University of Pennsylvania Health System. The institutional review board of the University of Pennsylvania approved the study and waived written informed consent given the use of deidentified prescribing data.

The study population included patients with breast, lung, or prostate cancer who were prescribed zoledronate or denosumab from 2016 to 2018. We categorized patients according to nudge exposure: (1) site A, the main cancer center where clinical leadership endorsed zoledronate and presented performance feedback at quarterly meetings and via email; (2) site B, a community affiliate and voluntary participant in the Oncology Care Model, where in addition there was accountable justification, in which denosumab prescription required justification to pharmacy; and (3) other sites, which continued usual practice and served collectively as a control group. Nudges were implemented in the second quarter of 2017.

We conducted a 3-group, interrupted time series analysis using multivariable logistic regression, accounting for clustering within patient-prescriber combinations. Models were fitted for the primary outcome of zoledronate prescription (vs denosumab). The independent variable was nudge exposure, interacted with study phase. A time-varying covariate represented 3 study phases: preimplementation (months 1-14), phase-in (months 15-21), and postimplementation (months 22-36). We excluded the phase-in from the main analysis. Covariates included age, sex, race, ethnicity, tumor type, and a monthly time trend.

We estimated the average marginal effect of each exposure as of December 2018 as the absolute percentage-point difference between preimplementation and postimplementation predicted probabilities of zoledronate prescription. An interaction between nudge exposure and study phase facilitated comparisons of each nudge’s marginal effect vs control. All tests were 2-sided with an α of 0.025 (corrected for 2 comparisons), using Stata statistical software (version 16, StataCorp).

Results

Across 7 practice sites, 220 clinicians prescribed 14 701 zoledronate or denosumab prescriptions to 2595 patients (1926 [74.2%] women) with breast (1528 [58.9%]), lung (730 [28.1%]), or prostate (337 [13.0%]) cancer. The mean (SD) age was 62.7 (12.3), 67.0 (12.7), and 66.8 (11.9) years at sites A, B, and other, respectively.

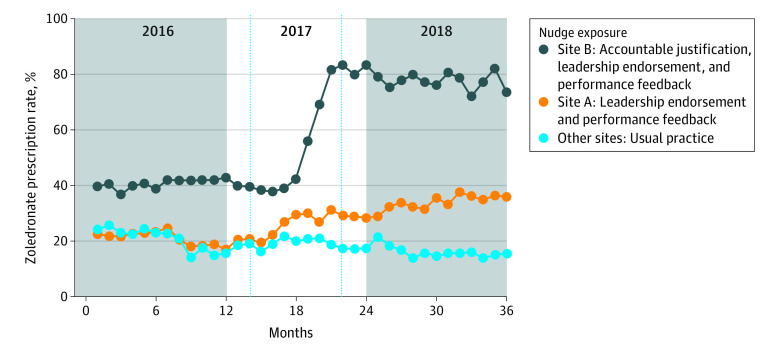

The Figure shows unadjusted trends in monthly zoledronate prescription by nudge exposure. As of December 2018, nudges were associated with statistically significant increases in the probability of zoledronate prescription compared with the control: site A, 26.0 percentage-point increase (95% CI, 18.5-33.4; P < .001 with leadership endorsement and performance feedback), and site B, 44.9 percentage-point increase (95% CI, 18.5-71.4; P = .001 with additionally accountable justification) (Table). Results were robust to exclusion of clinicians practicing at multiple sites (n = 22).

Figure. Unadjusted Trends in Zoledronate Prescription by Nudge Exposure.

Clinician-targeted behavorial nudges favoring zoledronate (vs denosumab) were implemented at site A (leadership endorsement and performance feedback) and site B (additionally, accountable justification) in University of Pennsylvania Health System (UPHS), beginning in the second quarter of 2017. The other 5 UPHS sites continued usual practice and served collectively as the control group. The vertical hashed lines demarcate the phase-in period for nudges at sites A and B.

Table. Interrupted Time Series Models of Zoledronate Prescription by Nudge Exposure and Compared With Controla.

| Nudge exposure | Patients, no. | Clinicians, no. | Predicted probability of zoledronate prescription, December 2018, % (95% CI) | Percentage-point increase (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preimplementation model | Postimplementation model | Marginal effect, adjusted | Marginal effect compared with control, adjusted | |||

| Site A (leadership endorsement and performance feedback) | 1314 | 108 | 2.1 (0.2 to 4.0) | 37.2 (32.4 to 42.1) | 35.1 (30.0 to 40.3) | 26.0 (18.5 to 33.4)b |

| Site B (accountable justification, leadership endorsement and performance feedback) | 282 | 26 | 22.7 (−2.2 to 47.5) | 76.8 (66.9 to 86.7) | 54.1 (28.2 to 80.0) | 44.9 (18.5 to 71.4)c |

| Other (usual practice) | 999 | 86 | 3.5 (−0.5 to 7.5) | 12.7 (8.9 to 16.4) | 9.2 (3.8 to 14.5) | NA |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Marginal effects of nudges on zoledronate prescription compared with usual practice (control). The estimated average marginal effect of each nudge exposure as of December 2018 (approximately 18 months after implementation) is the absolute percentage-point difference between preimplementation and postimplementation predicted probabilities of zoledronate prescription. The probability of zoledronate prescription predicted from the preimplementation model assumes that preimplementation trends persisted in the postimplementation period, whereas that predicted from the postimplementation model is based on postimplementation trends only. Interactions between nudge exposure and study phase facilitated comparisons of the marginal effects of each nudge exposure vs control. Models are adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity, tumor type, and a monthly time trend.

P < .001.

P = .001.

Discussion

In a large academic health system, behavioral nudges were associated with substantial increases in zoledronate prescription. Limitations include the potential for clinician contamination between sites, which was minimal and did not affect results, and the nonrandomized, observational research design. Our study findings demonstrate that nudges can powerfully promote high-value, evidence-based specialty drug prescribing and suggest a dose-response relationship warranting further study.

References

- 1.Prasad V, De Jesús K, Mailankody S. The high price of anticancer drugs: origins, implications, barriers, solutions. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017;14(6):381-390. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meeker D, Linder JA, Fox CR, et al. Effect of behavioral interventions on inappropriate antibiotic prescribing among primary care practices: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(6):562-570. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bach PB. Reforming the payment system for medical oncology. JAMA. 2013;310(3):261-262. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.8127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Poznak C, Somerfield MR, Barlow WE, et al. Role of bone-modifying agents in metastatic breast cancer: an American Society of Clinical Oncology-Cancer Care Ontario Focused Guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(35):3978-3986. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.75.4614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saylor PJ, Rumble RB, Tagawa S, et al. Bone health and bone-targeted therapies for prostate cancer: ASCO endorsement of a Cancer Care Ontario Guideline [published online January 28, 2020]. J Clin Oncol. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.03148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Intervention Ladder Public health: ethical issues. Nuffield Council on Bioethics; 2007:41-43. [Google Scholar]