Abstract

This case report describes a pregnant woman with symptomatic coronavirus disease who experienced a second-trimester miscarriage in association with documented placental SARS-CoV-2 infection.

No data exist regarding the effect on fetuses of maternal severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection during the first or second trimester of pregnancy, and data are limited regarding infections that occur during the third trimester. However, reports of newborns with fetal distress or requiring admission to the intensive care unit1,2 and a stillbirth after maternal coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)3 in the third trimester suggest the possibility of COVID-19–induced placental pathology.

We present a case of miscarriage during the second trimester in a pregnant woman with COVID-19.

Methods

A pregnant woman in her second trimester who had a miscarriage was evaluated at Lausanne University Hospital on March 20, 2020. Institutional review board approval and written informed consent were obtained. Information was obtained from medical records. Reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) to detect SARS-CoV-2 and cultures to detect bacterial pathogens and PCR for Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Mycoplasma hominis, and Ureaplasma urealyticum were performed on samples from the mother, fetus, and placenta (Table). Placental histological examination and fetal autopsy were performed by 2 experienced perinatal pathologists (C.G. and E.D.). Hematoxylin-eosin, myeloperoxidase immunohistochemistry, Gram, and periodic acid–Schiff colorations were performed on the placenta.

Table. SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR Resultsa.

| Sample type | SARS-CoV-2 results | Bacterial culture and RT-PCR |

|---|---|---|

| Maternal | ||

| Deep nasopharyngeal (March 18) | Positive | |

| Deep nasopharyngeal control (March 22) | Positive | |

| Vagina (March 20 and March 22) | Negative | Normal flora |

| Blood (March 22) | Negative | |

| Fetus (March 20) | ||

| Umbilical cord blood | Negative | |

| Amniotic fluid | Negative | Sterile |

| Fetal mouth | Negative | |

| Fetal armpit (2 samples) | Negative | |

| Placental submembrane | Positive | Sterile |

| Placental cotyledon | Positive | Sterile |

| Fetal anus | Negative | |

| Fetal liver | Negative | |

| Fetal thymus | Negative | |

| Fetal lung | Negative |

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was detected by coupling a MagNA Pure (Roche) RNA extraction to a 1-step reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) targeting the gene coding for the E protein of the virus.

Results

A 28-year-old obese, primigravida woman presented at 19 weeks’ gestation with fever (102.5 °F [39.2 °C]), myalgia, fatigue, mild pain with swallowing, diarrhea, and dry cough for 2 days. A nasopharyngeal swab was positive for SARS-CoV-2. She was given oral acetaminophen and discharged home.

Two days later, she presented with severe uterine contractions, fever, and no improvement of her symptoms. Physical examination did not reveal any signs of pneumonia. Vaginal examination demonstrated bulging membranes through a 5-cm dilated cervix. Active fetal movements; fetal tachycardia (180/min); and normal fetal morphology, growth, and amniotic fluid were detected on ultrasound. Prophylactic amoxicillin–clavulanic acid and regional anesthesia were started. The patient wore a mask throughout her labor, as did 2 health care professionals who both tested negative for SARS-CoV-2. Amniotic fluid and vaginal swabs sampled during labor tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 and bacterial infection (Table).

A stillborn infant was delivered vaginally after 10 hours of labor. Swabs from the axillae, mouth, meconium, and fetal blood obtained within minutes of birth tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 and bacterial infection. Fetal autopsy showed no malformations, and fetal lung, liver, and thymus biopsies were negative for SARS-CoV-2.

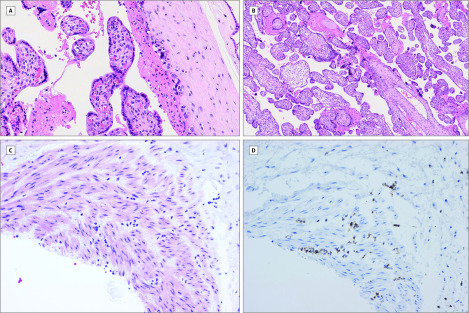

Within minutes of placental expulsion, the fetal surface of the placenta was disinfected and incised with a sterile scalpel, and 2 swabs and biopsies (close to the umbilical cord and peripheral margin) were obtained. All were negative for bacterial infection but were positive for SARS-CoV-2. At 24 hours, the placenta remained positive for SARS-CoV-2. At 48 hours, maternal blood, urine, and vaginal swab were all negative for SARS-CoV-2, whereas a nasopharyngeal swab remained positive. Placental histology demonstrated mixed inflammatory infiltrates composed of neutrophils and monocytes in the subchorial space and unspecific increased intervillous fibrin deposition (Figure). Funisitis (inflammation of the umbilical cord connective tissue suggesting fetal inflammatory response) was also present. Gram and periodic acid–Schiff staining of the placenta, PCR, and culture did not identify any bacterial or fungal infections.

Figure. Placental Histology.

A, Neutrophils and macrophages in the subchorial space indicating acute subchorionitis (hematoxylin-eosin ×20). B, Increased intervillous fibrin deposit and syncytial knots (hematoxylin-eosin ×10). C, Funisitis and umbilical cord vasculitis (hematoxylin-eosin ×20). D, Funisitis with neutrophil-specific staining (myeloperoxidase immunohistochemistry ×20).

Discussion

This case of miscarriage during the second trimester of pregnancy in a woman with COVID-19 appears related to placental infection with SARS-CoV-2, supported by virological findings in the placenta. Contamination at the time of delivery, sampling, or laboratory evaluation is unlikely, as all other swabs were negative for SARS-CoV-2. No other cause of fetal demise was identified. There was no evidence of vertical transmission, but absence of the virus is not surprising given the stage of fetal development and short time of maternal infection. Whether SARS-CoV-2 crosses the placental barrier warrants further investigation.4

Limitations include the single case and that other causes of miscarriage, such as spontaneous preterm birth, cervical insufficiency, or undetected systemic or local bacterial infection, cannot be ruled out.

Infection of the maternal side of the placenta inducing acute or chronic placental insufficiency resulting in subsequent miscarriage or fetal growth restriction was observed in 40% of maternal infections with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus.5,6 Additional study of pregnant women with COVID-19 is warranted to determine if SARS-CoV-2 can cause similar adverse outcomes.

Section Editor: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor.

References

- 1.Chen H, Guo J, Wang C, et al. . Clinical characteristics and intrauterine vertical transmission potential of COVID-19 infection in nine pregnant women: a retrospective review of medical records. Lancet. 2020;395(10226):809-815. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30360-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu H, Wang L, Fang C, et al. . Clinical analysis of 10 neonates born to mothers with 2019-nCoV pneumonia. Transl Pediatr. 2020;9(1):51-60. doi: 10.21037/tp.2020.02.06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu Y, Chen H, Tang K, Guo Y. Clinical manifestations and outcome of SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy. J Infect. 2020;S0163-4453(20)30109-2. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.02.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kimberlin DW, Stagno S. Can SARS-CoV-2 infection be acquired in utero? more definitive evidence is needed. JAMA. Published online March 26, 2020. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Favre G, Pomar L, Musso D, Baud D. 2019-nCoV epidemic: what about pregnancies? Lancet. 2020;395(10224):e40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30311-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong SF, Chow KM, Leung TN, et al. . Pregnancy and perinatal outcomes of women with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(1):292-297. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2003.11.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]