Abstract

Background

Acne is an inflammatory disorder with a high global burden. It is common in adolescents and primarily affects sebaceous gland‐rich areas. The clinical benefit of the topical acne treatments azelaic acid, salicylic acid, nicotinamide, sulphur, zinc, and alpha‐hydroxy acid is unclear.

Objectives

To assess the effects of topical treatments (azelaic acid, salicylic acid, nicotinamide, zinc, alpha‐hydroxy acid, and sulphur) for acne.

Search methods

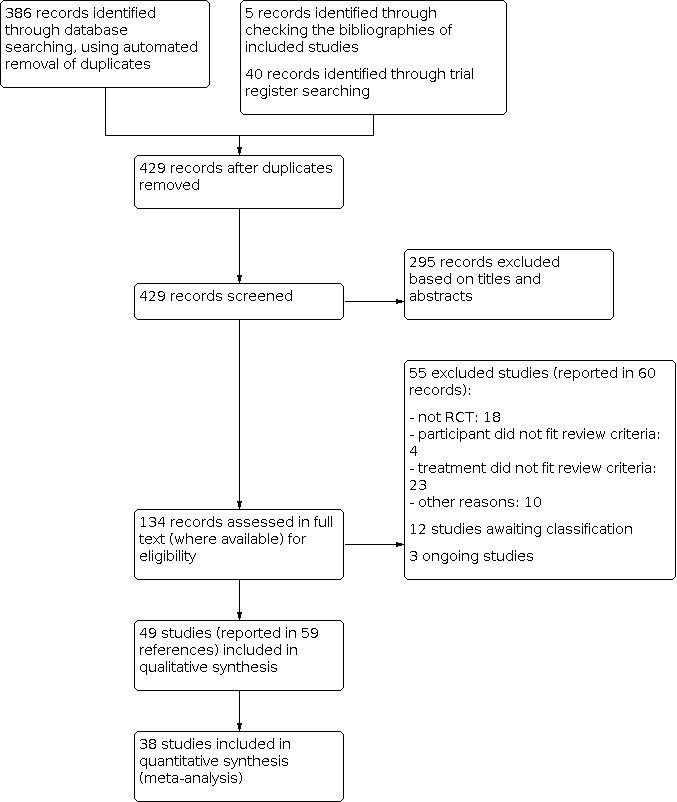

We searched the following databases up to May 2019: the Cochrane Skin Group Specialised Register, CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, and LILACS. We also searched five trials registers.

Selection criteria

Clinical randomised controlled trials of the six topical treatments compared with other topical treatments, placebo, or no treatment in people with acne.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures expected by Cochrane. Key outcomes included participants' global self‐assessment of acne improvement (PGA), withdrawal for any reason, minor adverse events (assessed as total number of participants who experienced at least one minor adverse event), and quality of life.

Main results

We included 49 trials (3880 reported participants) set in clinics, hospitals, research centres, and university settings in Europe, Asia, and the USA.

The vast majority of participants had mild to moderate acne, were aged between 12 to 30 years (range: 10 to 45 years), and were female. Treatment lasted over eight weeks in 59% of the studies. Study duration ranged from three months to three years.

We assessed 26 studies as being at high risk of bias in at least one domain, but most domains were at low or unclear risk of bias.

We grouped outcome assessment into short‐term (less than or equal to 4 weeks), medium‐term (from 5 to 8 weeks), and long‐term treatment (more than 8 weeks). The following results were measured at the end of treatment, which was mainly long‐term for the PGA outcome and mixed length (medium‐term mainly) for minor adverse events.

Azelaic acid

In terms of treatment response (PGA), azelaic acid is probably less effective than benzoyl peroxide (risk ratio (RR) 0.82, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.72 to 0.95; 1 study, 351 participants), but there is probably little or no difference when comparing azelaic acid to tretinoin (RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.78 to 1.14; 1 study, 289 participants) (both moderate‐quality evidence). There may be little or no difference in PGA when comparing azelaic acid to clindamycin (RR 1.13, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.38; 1 study, 229 participants; low‐quality evidence), but we are uncertain whether there is a difference between azelaic acid and adapalene (1 study, 55 participants; very low‐quality evidence).

Low‐quality evidence indicates there may be no differences in rates of withdrawal for any reason when comparing azelaic acid with benzoyl peroxide (RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.60 to 1.29; 1 study, 351 participants), clindamycin (RR 1.30, 95% CI 0.48 to 3.56; 2 studies, 329 participants), or tretinoin (RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.29 to 1.47; 2 studies, 309 participants), but we are uncertain whether there is a difference between azelaic acid and adapalene (1 study, 55 participants; very low‐quality evidence).

In terms of total minor adverse events, we are uncertain if there is a difference between azelaic acid compared to adapalene (1 study; 55 participants) or benzoyl peroxide (1 study, 30 participants) (both very low‐quality evidence). There may be no difference when comparing azelaic acid to clindamycin (RR 1.50, 95% CI 0.67 to 3.35; 1 study, 100 participants; low‐quality evidence). Total minor adverse events were not reported in the comparison of azelaic acid versus tretinoin, but individual application site reactions were reported, such as scaling.

Salicylic acid

For PGA, there may be little or no difference between salicylic acid and tretinoin (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.09; 1 study, 46 participants; low‐quality evidence); we are not certain whether there is a difference between salicylic acid and pyruvic acid (1 study, 86 participants; very low‐quality evidence); and PGA was not measured in the comparison of salicylic acid versus benzoyl peroxide.

There may be no difference between groups in withdrawals when comparing salicylic acid and pyruvic acid (RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.53 to 1.50; 1 study, 86 participants); when salicylic acid was compared to tretinoin, neither group had withdrawals (both based on low‐quality evidence (2 studies, 74 participants)). We are uncertain whether there is a difference in withdrawals between salicylic acid and benzoyl peroxide (1 study, 41 participants; very low‐quality evidence).

For total minor adverse events, we are uncertain if there is any difference between salicylic acid and benzoyl peroxide (1 study, 41 participants) or tretinoin (2 studies, 74 participants) (both very low‐quality evidence). This outcome was not reported for salicylic acid versus pyruvic acid, but individual application site reactions were reported, such as scaling and redness.

Nicotinamide

Four studies evaluated nicotinamide against clindamycin or erythromycin, but none measured PGA. Low‐quality evidence showed there may be no difference in withdrawals between nicotinamide and clindamycin (RR 1.12, 95% CI 0.49 to 2.60; 3 studies, 216 participants) or erythromycin (RR 1.40, 95% CI 0.46 to 4.22; 1 study, 158 participants), or in total minor adverse events between nicotinamide and clindamycin (RR 1.20, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.99; 3 studies, 216 participants; low‐quality evidence). Total minor adverse events were not reported in the nicotinamide versus erythromycin comparison.

Alpha‐hydroxy (fruit) acid

There may be no difference in PGA when comparing glycolic acid peel to salicylic‐mandelic acid peel (RR 1.06, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.26; 1 study, 40 participants; low‐quality evidence), and we are uncertain if there is a difference in total minor adverse events due to very low‐quality evidence (1 study, 44 participants). Neither group had withdrawals (2 studies, 84 participants; low‐quality evidence).

Authors' conclusions

Compared to benzoyl peroxide, azelaic acid probably leads to a worse treatment response, measured using PGA. When compared to tretinoin, azelaic acid probably makes little or no difference to treatment response. For other comparisons and outcomes the quality of evidence was low or very low.

Risk of bias and imprecision limit our confidence in the evidence. We encourage the comparison of more methodologically robust head‐to‐head trials against commonly used active drugs.

Keywords: Adolescent, Adult, Child, Female, Humans, Male, Young Adult, Acne Vulgaris, Acne Vulgaris/drug therapy, Adapalene, Adapalene/adverse effects, Adapalene/therapeutic use, Anti-Bacterial Agents, Anti-Bacterial Agents/therapeutic use, Benzoyl Peroxide, Benzoyl Peroxide/therapeutic use, Bias, Clindamycin, Clindamycin/adverse effects, Clindamycin/therapeutic use, Dermatologic Agents, Dermatologic Agents/adverse effects, Dermatologic Agents/therapeutic use, Dicarboxylic Acids, Dicarboxylic Acids/adverse effects, Dicarboxylic Acids/therapeutic use, Erythromycin, Erythromycin/adverse effects, Erythromycin/therapeutic use, Glycolates, Glycolates/therapeutic use, Keratolytic Agents, Keratolytic Agents/therapeutic use, Mandelic Acids, Mandelic Acids/therapeutic use, Niacinamide, Niacinamide/adverse effects, Niacinamide/therapeutic use, Patient Dropouts, Patient Dropouts/statistics & numerical data, Pyruvic Acid, Pyruvic Acid/adverse effects, Pyruvic Acid/therapeutic use, Quality of Life, Salicylic Acid, Salicylic Acid/therapeutic use, Sulfur, Sulfur/therapeutic use, Tretinoin, Tretinoin/therapeutic use, Zinc, Zinc/therapeutic use

Plain language summary

Topical azelaic acid, salicylic acid, nicotinamide, sulphur, zinc, and fruit acid (alpha‐hydroxy acid) for acne

Background

Acne vulgaris ('acne') is a costly and common skin disorder in which hair follicles become blocked. Acne affects up to 85% of adolescents and young adults. Topical retinoids (treatment derived from vitamin A) and antimicrobials (treatment that kills micro‐organisms such as bacteria) are common treatments. Other topical medications are also used, but there are concerns about their efficacy and safety.

Review question

This Cochrane Review aimed to assess the effects of six topical treatments (azelaic acid, salicylic acid, nicotinamide, sulphur, zinc, and alpha‐hydroxy acid (organic acids found in food, sometimes known as fruit acid) on people with acne when compared with an inactive substance (placebo), no treatment, or other topical treatments. The evidence is current to May 2019.

Study characteristics

We included 49 trials (3880 reported participants). At least one study assessed each eligible treatment.

Most trial participants were female, aged between 12 and 30 years, with mild to moderate acne. Nearly 60% of the trials treated participants for longer than eight weeks. Study duration ranged from three months to three years.

Nine trials reported pharmaceutical support. The studies were mainly conducted in Europe, Asia, and the USA, in clinics, hospitals, research centres, and universities.

Key results

The following results were measured at the end of treatment, which was mainly long term (more than 8 weeks) for the outcome 'Participants' global self‐assessment of acne improvement' (PGA) and mixed in length, but mainly medium term (from 5 to 8 weeks), for 'Total number of participants who experienced at least one minor side effect'.

Azelaic acid probably leads to worse PGA when compared to benzoyl peroxide, but when compared to tretinoin, there is probably little or no difference (both moderate‐quality evidence). When comparing azelaic acid to clindamycin, there may be little or no difference in PGA (low‐quality evidence), but we are uncertain whether azelaic acid reduces PGA compared to adapalene (very low‐quality evidence).

In terms of participant withdrawal (for any reason), there may be no difference when azelaic acid is compared with benzoyl peroxide, clindamycin, and tretinoin (all low‐quality evidence). We are uncertain whether azelaic acid reduces withdrawals when compared to adapalene (very low‐quality evidence).

We are uncertain whether azelaic acid has fewer total minor adverse events when compared to adapalene or benzoyl peroxide (very‐low quality evidence). When comparing azelaic acid to clindamycin, there may be no difference in total adverse events (low‐quality evidence). The studies that compared azelaic acid with tretinoin only reported individual side effects (e.g. scaling).

We are uncertain if there is a difference between salicylic acid and pyruvic acid on PGA score (very low‐quality evidence). There may be little or no difference between salicylic acid and tretinoin in PGA (low‐quality evidence). No study comparing salicylic acid with benzoyl peroxide assessed PGA. There may be no difference in withdrawals when comparing salicylic acid and pyruvic acid; there were no withdrawals when salicylic acid was compared to tretinoin (both low‐quality evidence). We are uncertain if there is a difference in withdrawals between salicylic acid and benzoyl peroxide (very low‐quality evidence).

We are uncertain whether salicylic acid reduces total minor adverse events when compared to benzoyl peroxide or tretinoin (very low‐quality evidence). For salicylic acid compared with pyruvic acid only individual application site reactions were reported (e.g. scaling and redness).

None of the four studies assessing nicotinamide (compared to clindamycin or erythromycin) assessed PGA. Nicotinamide may make no difference to withdrawals when compared to clindamycin or erythromycin, and may make no difference to total minor adverse events when compared to clindamycin (both low‐quality evidence); however, no studies comparing nicotinamide with erythromycin looked at total minor adverse events.

Glycolic acid peels may make no difference to PGA when compared to salicylic‐mandelic acid peels (low‐quality evidence), we are uncertain of the effect on total minor adverse events (very low‐quality evidence), and there were no withdrawals (low‐quality evidence).

Quality of the evidence

Our evidence quality was mixed for the PGA outcome (very low to moderate), mainly low quality for withdrawals, and very low quality for total minor side effects. We had some concerns with the small size of the studies and how they were conducted.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Azelaic acid compared to adapalene.

| Azelaic acid compared to adapalene for acne | ||||||

| Patient or population: participants with acne Settings: industry‐sponsored, single‐site study in Germany (1 study) Intervention: topical azelaic acid Comparison: topical adapalene | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Topical adapalene | Topical azelaic acid | |||||

|

Participants' global self‐assessment of acne improvement Improved to very much improved (long term: treatment duration > 8 weeks) |

842 per 1000 | 749 per 1000 (573 to 985) | RR 0.89 (0.68 to 1.17) | 55 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa | ‐ |

|

Withdrawal for any reason (long term: treatment duration > 8 weeks) |

53 per 1000 | 139 per 1000 (17 to 1000) | RR 2.64 (0.33 to 20.99) | 55 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb | ‐ |

|

Total number of participants who experienced at least one minor adverse event (medium term: treatment duration from 5 to 8 weeks) |

263 per 1000 | 305 per 1000 (124 to 750) | RR 1.16 (0.47 to 2.85) | 55 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowc | The authors reported no "significant difference" in the incidence of erythema, dryness, and itching between treatment groups. |

|

Quality of life Dermatology Life Quality Index (long term: treatment duration > 8 weeks) |

The authors reported that there was no "statistically significant" difference (P = 0.549) between azelaic acid and adapalene. | 55 (1 study) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowd |

Skewed data reported. | ||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aDowngraded by three levels to very low quality evidence. One level for risk of bias: only one study included, and study had unclear allocation concealment and high risk of performance bias. Two levels for imprecision: wide CI and optimal sample size not met. bDowngraded by three levels to very low quality evidence. One level for risk of bias: only one study included, with unclear allocation concealment and high risk of performance bias. Two levels for imprecision: very wide CI and optimal sample size not met. cDowngraded by three levels to very low quality evidence. One level for risk of bias: only one study included, with high risk of performance bias and unclear allocation concealment and blinding of outcome assessment. Two levels for imprecision: wide CI and optimal sample size not met. dDowngraded by three levels to very low quality evidence. One level for risk of bias: only one study included with unclear allocation concealment and high risk of performance bias. Two levels for imprecision: very small population size. *We choose a mean baseline risk from the studies included in meta‐analysis, calculated as number of participants in the control groups with event divided by total number of participants in control groups (study population) as assumed risk.

Summary of findings 2. Azelaic acid compared to benzoyl peroxide.

| Azelaic acid compared to benzoyl peroxide for acne | ||||||

| Patient or population: participants with acne Settings: multicentres, recruitment in Germany, Netherlands, Norway, and Greece (1 study); not described (1 study) Intervention: topical azelaic acid Comparison: topical benzoyl peroxide | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Topical benzoyl peroxide | Topical azelaic acid | |||||

|

Participants' global self‐assessment of acne improvement Good or very good improvement (long term: treatment duration > 8 weeks) |

771 per 1000 | 633 per 1000 (555 to 733) | RR 0.82 (0.72 to 0.95) | 351 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | ‐ |

|

Withdrawal for any reason (long term: treatment duration > 8 weeks) |

246 per 1000 | 216 per 1000 (147 to 317) | RR 0.88 (0.60 to 1.29) | 351 (1 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb | ‐ |

|

Total number of participants who experienced at least one minor adverse event (short term: treatment duration ≤ 4 weeks) |

133 per 1000 | 67 per 1000 (7 to 659) | RR 0.50 (0.05 to 4.94) | 30 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowc | The authors reported that people in the azelaic acid group experienced less dryness and desquamation, but more itching when compared to those in the benzoyl peroxide group. |

| Quality of life | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Not measured |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aDowngraded by one level to moderate quality evidence. One level for risk of bias: only one study included with unclear risk of selection, performance bias and other bias, and with high risk of attrition and reporting bias. bDowngraded by two levels to low quality evidence. One level for risk of bias: only one study included with unclear risk of selection, performance bias and other bias, and with high risk of attrition and reporting bias. One level for imprecision: wide CI. cDowngraded by three levels to very low quality evidence. One level for risk of bias: only one study included with high risk of detection bias and unclear risk of selection, performance, attrition bias.Two levels for imprecision: wide CI and optimal sample size not met. *We choose a mean baseline risk from the studies included in meta‐analysis, calculated as number of participants in the control groups with event divided by total number of participants in control groups (study population) as assumed risk.

Summary of findings 3. Azelaic acid compared to clindamycin.

| Azelaic acid compared to clindamycin for acne | ||||||

| Patient or population: participants with acne Settings: multicentres, recruitment in Germany, Netherlands, Norway, and Greece (1 study); three clinics in Tehran (1 study) Intervention: topical azelaic acid Comparison: topical clindamycin | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Topical clindamycin | Topical azelaic acid | |||||

|

Participants' global self‐assessment of acne improvement Good or very good improvement (long term: treatment duration > 8 weeks) |

591 per 1000 | 668 per 1000 (544 to 816) | RR 1.13 (0.92 to 1.38) | 229 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa | ‐ |

|

Withdrawal for any reason (long term: treatment duration > 8 weeks) |

103 per 1000 | 134 per 1000 (49 to 367) | RR 1.30 (0.48 to 3.56) | 329 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb | ‐ |

|

Total number of participants who experienced at least one minor adverse event (long term: treatment duration > 8 weeks) |

160 per 1000 | 240 per 1000 | RR 1.5 (0.67 to 3.35) | 100 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowc | There was no difference in minor adverse events (such as scaling and dry skin) between azelaic acid 5% gel and clindamycin 2% gel. |

| Quality of life | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Not measured |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aDowngraded by two levels to low quality evidence. One level for risk of bias: only one study included with unclear risk of selection, performance, and other bias, and with high risk of attrition and reporting bias. One level for imprecision: wide CI and optimal sample size not met. bDowngraded by two levels to low quality evidence. One level for risk of bias: both studies had unclear risk of selection and performance bias, and one study had a high risk of attrition and reporting bias. One level for imprecision: wide CI and optimal sample size not met. cDowngraded by two levels to low quality evidence. One level for risk of bias: only one study included with unclear risk of selection, performance and detection bias. One level for imprecision: CI and optimal sample size not met. *We choose a mean baseline risk from the studies included in meta‐analysis, calculated as number of participants in the control groups with event divided by total number of participants in control groups (study population) as assumed risk.

Summary of findings 4. Azelaic acid compared to tretinoin.

| Azelaic acid compared to tretinoin for acne | ||||||

| Patient or population: participants with acne Settings: multicentres in one study; not described (1 study) Intervention: topical azelaic acid Comparison: topical tretinoin | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Topical tretinoin | Topical azelaic acid | |||||

|

Participants' global self‐assessment of acne improvement Good to excellent improvement (long term: treatment duration > 8 weeks) |

623 per 1000 | 586 per 1000 (486 to 711) | RR 0.94 (0.78 to 1.14) | 289 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | ‐ |

|

Withdrawal for any reason (long term: treatment duration > 8 weeks) |

90 per 1000 | 59 per 1000 (26 to 132) | RR 0.66 (0.29 to 1.47) | 309 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb | ‐ |

| Total number of participants who experienced at least one minor adverse event | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | Total number of participants who experienced at least one adverse event not reported. The rate of erythema and scaling was considerably higher in the tretinoin group than that in the azelaic acid group. |

| Quality of life | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Not measured |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aDowngraded by one level to moderate quality evidence. One level for risk of bias: only one study included with a high risk of attrition bias and unclear risk of selection and performance bias. bDowngraded by two levels to low quality evidence. One level for risk of bias: both studies with unclear risk of selection and performance bias, one study with high risk of attrition bias and the other with high risk of reporting bias. One level for imprecision: wide CI and optimal sample size not met. *We choose a mean baseline risk from the studies included in meta‐analysis, calculated as number of participants in the control groups with event divided by total number of participants in control groups (study population) as assumed risk.

Summary of findings 5. Salicylic acid compared to benzoyl peroxide.

| Salicylic acid compared to benzoyl peroxide for acne | ||||||

| Patient or population: participants with acne Settings: not described Intervention: topical salicylic acid Comparison: topical benzoyl peroxide | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Topical benzoyl peroxide | Topical salicylic acid | |||||

| Participants' global self‐assessment of acne improvement | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Not measured |

|

Withdrawal for any reason (medium term: treatment duration from 5 to 8 weeks) |

See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 41 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa | Neither treatment group had any withdrawals. |

|

Total number of participants who experienced at least one minor adverse event (medium term: treatment duration from 5 to 8 weeks) |

95 per 1000 | 20 per 1000 (1 to 391) | RR 0.21 (0.01 to 4.11) | 41 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb | The authors reported that zero out of 20 people in the 2% salicylic acid microgel group versus two out of 21 people in the benzoyl peroxide 10% cream group experienced minor adverse events. |

|

Quality of life ARQL (medium term: treatment duration from 5 to 8 weeks) |

The authors stated that subjects treated with salicylic acid microgel experienced better improvement when compared to 10% benzoyl peroxide. | 41 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowc |

No numerical data reported. | ||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). ARQL: acne‐related quality of life; CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aDowngraded by three levels to very low quality evidence. One level for risk of bias: only one study included with unclear risk of selection, performance, detection, and reporting bias. Two levels for imprecision: very small total sample size. bDowngraded by three levels to very low quality evidence. One level for risk of bias: only one study included with unclear selection, performance, and reporting bias. Two levels for imprecision: wide CI and optimal sample size not met. cDowngraded by three levels to very low quality evidence. One level for risk of bias: only one study included with unclear risk of selection, performance, detection, and reporting bias. Two levels for imprecision: very small total sample size. *We choose a mean baseline risk from the studies included in meta‐analysis, calculated as number of participants in the control groups with event divided by total number of participants in control groups (study population) as assumed risk.

Summary of findings 6. Salicylic acid compared to pyruvic acid.

| Salicylic acid compared to pyruvic acid for acne | ||||||

| Patient or population: participants with acne Settings: Al‑Zahra Hospital Dermatology Clinic and Isfahan Skin Research Centre Intervention: topical salicylic acid Comparison: topical pyruvic acid | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Topical pyruvic acid | Topical salicylic acid | |||||

|

Participants' global self‐assessment of acne improvement Good to excellent improvement (medium term: treatment duration from 5 to 8 weeks) |

395 per 1000 | 443 per 1000 (269 to 727) | RR 1.12 (0.68 to 1.84) | 86 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa | ‐ |

|

Withdrawal for any reason (medium term: treatment duration from 5 to 8 weeks) |

419 per 1000 | 373 per 1000 (222 to 628) | RR 0.89 (0.53 to 1.50) | 86 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb | ‐ |

| Total number of participants who experienced at least one minor adverse event | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | Total number of participants who experienced at least one adverse event not reported. Although the authors did report no "significant difference" in minor adverse events (scaling in the first to fourth sessions, redness, burning, and itching) between the two peeling (30% salicylic acid and 50% pyruvic acid). |

| Quality of life | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Not measured |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aDowngraded by three levels to very low quality evidence. Two levels for risk of bias: only one study included with high risk of attrition and other bias and unclear risk of selection and performance bias. One level for imprecision: wide CI and optimal sample size is not met. bDowngraded by two levels to low quality evidence. One level for imprecision: wide CI and optimal sample size not met. One level for risk of bias: only one study included with high risk of attrition and other bias, and unclear risk of selection and performance bias. *We choose a mean baseline risk from the studies included in meta‐analysis, calculated as number of participants in the control groups with event divided by total number of participants in control groups (study population) as assumed risk.

Summary of findings 7. Salicylic acid compared to tretinoin.

| Salicylic acid compared to tretinoin for acne | ||||||

| Patient or population: participants with acne Settings: Skin Disease and Leishmaniasis Research Center and Isfahan University of Medical Sciences clinics (1 study); not described (1 study) Intervention: topical salicylic acid Comparison: topical tretinoin | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Topical tretinoin | Topical salicylic acid | |||||

|

Participants' global self‐assessment of acne improvement

Moderate to excellent improvement (long term: treatment duration > 8 weeks) |

1000 per 1000 | 1000 per 1000 (920 to 1000) | RR 1.00 (0.92 to 1.09) | 46 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa | ‐ |

|

Withdrawal for any reason (long term: treatment duration > 8 weeks) |

See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 74 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb | Neither study had any withdrawals. |

|

Total number of participants who experienced at least one minor adverse event (long term: treatment duration > 8 weeks) |

541 per 1000 | 741 per 1000 (357 to 1000) | RR 1.37 (0.66 to 2.87) | 74 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowc | The authors in one study reported no "statistically significant" differences in the incidence of dryness, peeling, erythema, burning and itching between treatment groups at any study week. All side effects reported in the two studies were of mild to moderate intensity and transient. |

|

Quality of life AQOL (long term: treatment duration > 8 weeks) |

The authors reported no "significant differences" in AQOL between salicylic acid group (end of study: 0.95 ± 1.9) and tretinoin group (end of study: 0.91 ± 1.64) at baseline and at the end of the study | 46 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowd |

Skewed data reported. | ||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). AQOL: acne quality of life; CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aDowngraded by two levels to low quality evidence. One level for risk of bias: only one study included with unclear risk of random sequence generation, allocation concealment, and blinding of participants and personnel. One level for imprecision: optimal sample size not met. bDowngraded by two levels to low quality evidence. One level for risk of bias: both studies with unclear risk of selection bias, one with unclear risk of performance bias and the other with high risk of performance and unclear risk of reporting bias. One level for imprecision: small total sample size. cDowngraded by three levels to very low quality evidence. One level for risk of bias: two studies with unclear risk of selection bias and high risk of detection bias. Two levels for imprecision: wide CI and optimal sample size not met. dDowngraded by three levels to very low quality evidence. One level for risk of bias: only one study included with unclear risk of random sequence generation, allocation concealment, and blinding of participants and personnel. Two levels for imprecision: very small population size and wide CI. *We choose a mean baseline risk from the studies included in meta‐analysis, calculated as number of participants in the control groups with event divided by total number of participants in control groups (study population) as assumed risk.

Summary of findings 8. Nicotinamide compared to clindamycin.

| Nicotinamide compared to clindamycin for acne | ||||||

| Patient or population: participants with acne Settings: multicentres in USA (1 study); a teaching clinic of dermatology in Iran (1 study); St‐Alzahra hospital, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran (1 study) Intervention: topical nicotinamide Comparison: topical clindamycin | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Topical clindamycin | Topical nicotinamide | |||||

| Participants' global self‐assessment of acne improvement | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Not measured |

|

Withdrawal for any reason (medium term: treatment duration from 5 to 8 weeks) |

74 per 1000 | 83 per 1000 (36 to 193) | RR 1.12 (0.49 to 2.60) | 216 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa | Two trials had no withdrawals. |

|

Total number of participants who experienced at least one minor adverse event (medium term: treatment duration from 5 to 8 weeks) |

185 per 1000 | 222 per 1000 (135 to 369) | RR 1.20 (0.73 to 1.99) | 216 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb | Local application site reactions (e.g. itching, burning, crusting) were reported in two studies. In the third study, the authors reported no side effects during the treatment. |

| Quality of life | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Not measured |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aDowngraded by two levels to low quality evidence. One level for risk of bias: three studies included and all with unclear risk of bias, two with unclear risk of performance bias, one with high risk of attrition bias. One level for imprecision: wide CI and optimal sample size not met. bDowngraded by two levels to low quality evidence. One level for risk of bias: all three studies with unclear risk of selection and detection bias, two out of three studies with unclear risk of performance bias. One level for imprecision: wide CI and optimal sample size not met. *We choose a mean baseline risk from the studies included in meta‐analysis, calculated as number of participants in the control groups with event divided by total number of participants in control groups (study population) as assumed risk.

Summary of findings 9. Nicotinamide compared to erythromycin.

| Nicotinamide compared to erythromycin for acne | ||||||

| Patient or population: participants with acne Settings: Laboratoire Dermscan (Villeurbanne) Intervention: topical nicotinamide Comparison: topical erythromycin | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Topical erythromycin | Topical nicotinamide | |||||

| Participants' global self‐assessment of acne improvement | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Not measured |

|

Withdrawal for any reason (medium term: treatment duration from 5 to 8 weeks) |

63 per 1000 | 89 per 1000 (29 to 267) | RR 1.40 (0.46 to 4.22) | 158 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa | ‐ |

| Total number of participants who experienced at least one minor adverse event | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | Total number of participants who experienced at least one adverse event not reported. There was "no difference" in occurrence of pertinent clinical signs and functional or physical signs between treatment groups. |

| Quality of life | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Not measured |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aDowngraded by two levels to low quality evidence. One level for risk of bias: only one study included with unclear risk of selection and performance bias. One level for imprecision: wide CI and optimal sample size not met. *We choose a mean baseline risk from the studies included in meta‐analysis, calculated as number of participants in the control groups with event divided by total number of participants in control groups (study population) as assumed risk.

Summary of findings 10. Glycolic acid (alpha‐hydroxy acid) compared to salicylic‐mandelic acid.

| Glycolic acid (alpha‐hydroxy acid) compared to salicylic‐mandelic acid for acne | ||||||

| Patient or population: participants with acne Settings: Dermatology and Andrology Department of Beha University hospital, Egyptian patients (only study); recruitment in India (1 study) Intervention: topical glycolic acid (alpha‐hydroxy acid) Comparison: topical salicylic‐mandelic acid | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Topical salicylic‐mandelic acid | Topical glycolic acid | |||||

|

Participants' global self‐assessment of acne improvement Fair to good improvement (long term: treatment duration > 8 weeks) |

900 per 1000 | 954 per 1000 (792 to 1000) | RR 1.06 (0.88 to 1.26) | 40 (1 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa | ‐ |

|

Withdrawal for any reason (long term: treatment duration > 8 weeks) |

See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 84 (2 studies) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb | Neither study had any withdrawals. |

|

Total number of participants who experienced at least one minor adverse event (long term: treatment duration > 8 weeks) |

227 per 1000 | 409 per 1000 (164 to 1000) | RR 1.80 (0.72 to 4.52) | 44 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowc | Four (20%) participants in salicylic‐mandelic acid peel experienced a burning or stinging sensation against two (10%) in glycolic acid peel. Sixteen participants (80%) in salicylic‐mandelic acid peel developed visible desquamation against eight (40%) in glycolic acid peel (P = 0.025). |

| Quality of life | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Not measured |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aDowngraded by two levels to low quality evidence. Two levels for imprecision: wide CI and optimal sample size not met. bDowngraded by two levels to low quality evidence. One level for risk of bias: two studies included, one with unclear risk of selection, performance and reporting bias, the other with unclear risk of performance bias. One level for imprecision: small total sample size. cDowngraded by three levels to very low quality evidence. One level for risk of bias: only one study included with high risk of detection bias and unclear risk of selection, performance bias. Two levels for imprecision: wide CI and optimal sample size not met. *We choose a mean baseline risk from the studies included in meta‐analysis, calculated as number of participants in the control groups with event divided by total number of participants in control groups (study population) as assumed risk.

Background

Please see the glossary in Table 11 for an explanation of medical terms used throughout the text.

1. Glossary of medical terms.

| Medical term | Explanation |

| Acne vulgaris | A common chronic skin disorder of sebaceous follicles, mainly affecting the face, chest, and backa |

| Chemokine | A group of small cytokines that act as chemical messengers to induce chemotaxis in leukocytesc |

| Comedone | A clogged hair follicle in the skin. It can present as a blackhead or whiteheada |

| Cytokine | A small protein released by cells that function as molecular messengers between cellsc |

| Erythema | Redness of the skin, caused by vascular congestion or increased perfusionb |

| Hyperkeratosis | Thickening of the outer layer of skin often associated with a quantitative abnormality of keratinb |

| Keratinocytes | The predominant cell type in the epidermis, forming a touch protective layera |

| Microcomedones | Early and small plugging of the follicle with excess keratin and sebumb |

| Nodule | A solid mass in the skin, more than 0.5 cm in diameterb |

| Papule | A circumscribed palpable elevation, less than 0.5 cm in diameterb |

| Pilosebaceous unit | A structure consisting of a hair follicle, sebaceous gland, and an arrector pili muscleb |

|

Propionibacterium acnes (Cutibacterium acnes) |

Gram‐positive bacterium related to acne developmentb |

| Pustule | A visible accumulation of free pusb |

| Scar | Skin areas of fibrous tissue replacing normal skin after injuryb |

| Sebum | The oily, waxy substance produced by sebaceous glandsb |

| Stratum corneum | The outermost layer of the epidermis, where cells have lost nuclei and cytoplasmic organellesb |

| Toll‐like receptor | A class of proteins that recognise conserved products unique to microbial metabolism in immune responsec |

aAndrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology, 11th Edition, 2011, Elsevier Inc. bRook's Textbook of Dermatology, Eighth Edition, 2010, Blackwell Publishing Ltd. cImmunology, Sixth Edition, 2001, Harcourt Asia Pte Ltd.

Description of the condition

Acne is a common inflammatory disorder of pilosebaceous units (Landow 1997). It results in non‐inflammatory lesions known as comedones (whiteheads or blackheads) and inflammatory lesions including papules, pustules, or nodules (Ramli 2012). Acne primarily affects sebaceous gland‐rich areas, such as the face, shoulders, back, and upper chest (Katsambas 2008).

Acne comprises acne vulgaris, acne variants, and acneiform eruptions in clinical practice (Table 12). Acne vulgaris is the most common type of acne, which mainly affects adolescents and young adults. Prevalence in young people aged 12 to 24 years is as high as 85% (Bhate 2013). Acne severity in boys correlates with pubertal maturation. One study of healthy Danish boys showed that the mean age of onset of puberty has fallen from 11.92 between 1991 and 1993 to 11.66 between 2006 and 2008 (Sorensen 2010). Previous studies showed that 50% of boys aged 10 or 11 years had more than 10 comedones (Lucky 1991), and 78% of girls aged eight to 12 years had acne (Lucky 1997). Acne often begins in the early teens and it can persist through the third decade or even later, but the intensity and duration varies for each individual (Bhate 2013). Recently, several reports have suggested increased prevalence of an adult form of acne vulgaris (Khunger 2012; Rademaker 2014). Adult acne mainly affects women and the prevalence in adult women is estimated to be 14% (Williams 2006). In addition, although uncommon, physicians can come across people with childhood acne classified according to the age of onset (neonatal, infantile, mid‐childhood, and prepubertal) (Antoniou 2009; Krakowski 2007).

2. Clinical classification of acnea.

| Acne vulgaris | |

| Acne variants | Neonatal acne |

| Infantile acne | |

| Acne conglobata | |

| Acne fulminans | |

| SAPHO syndrome | |

| PAPA syndrome | |

| Acne excoriee des jeunes filles | |

| Acne mechanica | |

| Acne with solid facial oedema | |

| Acne with associated endocrinology abnormalities | |

| Acneiform eruptions | Steroid folliculitis |

| Drug‐induced acne | |

| Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor associated eruption | |

| Occupational acne and chloracne | |

| Gram‐negative folliculitis | |

| Radiation acne | |

| Tropical acne | |

| Acne aestivalis | |

| Pseudoacne of the nasal crease | |

| Apert syndrome |

aFitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine, Eighth edition, 2012, The McGraw‐Hill Companies, Inc.

To date, there are various grading systems for severity assessment, but with no consensus (Lehmann 2002; Ramli 2012). Moreover, there are no grading systems that fulfil all essential criteria required for an ideal acne grading scale (Tan 2012; Tan 2013). Acne experts suggest that scales served as investigator global assessment grading measures may be helpful to establish an ideal scale (Tan 2013). There are various grading systems used in clinical practice. According to the predominant types of lesions, study authors can classify acne vulgaris as comedonal, papulopustular, and nodular acne (Ramli 2012), or classify acne vulgaris as mild, moderate, severe, and cystic acne (Dayal 2017). However, when the predominant lesion type is difficult to determine, physicians may consider it as polymorphic acne (Kharfi 2001). Study authors may also classify acne vulgaris as mild, moderate, and severe based on the acne grading of the face, back and chest (O'Brien 1998). When conducting a clinical trial, study authors may classify acne based on different grading systems or scales such as the Allen‐Smith Scale (Aksakal 1997), Cunliffe grading system (Bae 2013), investigator's static global assessment score (Schaller 2016), and Michaelson acne severity index (Kar 2013). However, all the current acne grading systems have shortcomings and a consistently applied standard for grading acne severity is urgently needed (Tan 2013).

The mechanism that causes the disease is unknown, but it is widely accepted that increased sebum excretion induced by androgens, follicular hyperkeratinisation, Cutibacterium acnes (C acnes, formerly Propionibacterium acnes) (Dreno 2018), and bacterial hypercolonisation, as well as inflammation, are the major pathogenetic factors for acne (Friedlander 2010). A keratinous plug forms at the follicular infundibulum resulting from hyperkeratosis in the follicle, initiating the formation of microcomedones (Cunliffe 2000). Within these microcomedones is an anaerobic lipid‐rich environment suitable for the growth of C acnes (Brown 1998). The C acnes then hydrolyse triglycerides into glycerol and free fatty acids, which can initiate the inflammatory response (Dessinioti 2010; Thiboutot 2016). The cell surface toll‐like receptors, which play critical roles in the immune response against micro‐organisms, are involved in this bacteria‐mediated inflammatory response by triggering the release of pro‐inflammatory cytokines (Kim 2005).

Although acne vulgaris is not life‐threatening and usually regresses in the third decade (Thiboutot 2016), it may cause serious psychological distress, as well as pain, and may considerably compromise the quality of life of the individual. Embarrassment, shame, and lack of confidence are important consequences resulting from acne vulgaris. Furthermore, scarring and embarrassment from acne begins at approximately the same age that adolescents are undergoing significant emotional and physical changes which, if combined, can be devastating. Indeed, there have been reports suggesting that severe acne can result in permanent physical scarring and even suicidal ideation (Dunn 2011; Misery 2011).

Description of the intervention

Treatment options for acne are often targeted at the factors implicated in acne development, such as sebaceous hypersecretion, abnormal keratinisation, C acnes bacteria colonisation, and the inflammation process (Titus 2012). The choice of treatments depends on the type and extent of acne (Gollnick 2003). Topical therapy is the preferred choice of treatment for mild acne and is also useful for moderate to severe acne (Akhavan 2003). The current mainstay of topical therapy for acne vulgaris includes retinoids (such as adapalene and tretinoin) and antimicrobials, such as benzoyl peroxide and antibiotics (Akhavan 2003; Titus 2012; Well 2013). However, other topical medications such as azelaic acid, salicylic acid, topical nicotinamide, sulphur, zinc, and alpha‐hydroxy acid (such as glycolic acid and mandelic acid) are also effective for acne treatment (Akhavan 2003; ElRefaei 2015; Habbema 1989; Shahmoradi 2013; Sharad 2013).

How the intervention might work

Topical azelaic acid

As an ingredient found in many whole grain cereals and animal products, azelaic acid is a well‐known aliphatic dicarboxylic acid, and it is useful in acne treatment due to its antimicrobial and anticomedonal properties (Akhavan 2003). Twice‐daily application of 20% cream formation (Azelex) (Titus 2012), approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for acne, can lead to an improvement of conditions within four weeks of initiation of therapy (Akhavan 2003; Cunliffe 1989). Compared to Azelex, the 15% gel (Finacea) has better bioavailability (Frampton 2004; Titus 2012). Azelaic acid 20% cream monotherapy or in combination therapy with glycolic acid (Graupe 1996; Spellman 1998), azelaic acid 20% (Iraji 2007) or 15% gel (Thiboutot 2008), azelaic acid 5% gel in combination with clindamycin 2% (Pazoki‐Toroudi 2011), or erythromycin 2% (Pazoki‐Toroudi 2010), are all effective treatments for acne. Azelaic acid 20% cream can reduce the number of both non‐inflammatory and inflammatory lesions and has an efficacy comparable to the other approved standard treatments, including benzoyl peroxide and erythromycin, as well as tretinoin, but it is better tolerated by people with fewer side effects (Simonart 2012; Spellman 1998).

Azelaic acid is able to competitively antagonise the activity of mitochondrial oxidoreductases and 5‐alpha‐reductase (Passi 1989; Stamatiadis 1988). The mechanism of action of azelaic acid in acne treatment may relate to its inhibitory effects on mitochondrial oxidoreductase and DNA synthesis (Fitton 1991). It has a predominant antibacterial activity on C acnes by inhibiting protein synthesis (Bojar 1991), and has a modest comedolytic effect by inhibiting the proliferation and differentiation of human keratinocytes, as well as an anti‐inflammatory action by inhibiting the generation of pro‐inflammatory oxygen derivatives in neutrophils (Akamatsu 1991; Sieber 2014). It can also reduce sebum production on the forehead, chin, and cheek through its inhibitory effect on the conversion from testosterone to 5‐dehydrotestosterone (Passi 1989).

Adverse effects of azelaic acid are mild and transient. About 5% to 10% of people report a burning or stinging sensation, tightness of the skin, and erythema in the treated area, but this usually only lasts for a few weeks (Graupe 1996). Azelaic acid can cause hypopigmentation, so physicians should monitor its use in people with dark skin (Akhavan 2003). Azelaic acid is a US FDA pregnancy category B drug. It has minimal systemic absorption when used topically. Use in pregnancy and lactation should not be a cause for concern (Bozzo 2011), although the excretion of azelaic acid into milk has been demonstrated, and caution is advised in nursing mothers (Akhavan 2003).

Topical salicylic acid

Salicylic acid is often incorrectly recognised as a beta‐hydroxy acid but it is actually an O‐hydroxybenzoic acid (Kempiak 2008), and it is useful in the treatment of acne vulgaris due to its keratolytic and comedolytic effects (Akarsu 2012; Akhavan 2003). Salicylic acid is a component of most over‐the‐counter acne preparations (Simonart 2012). Its concentration varies from 0.5% to 3.0% (Babayeva 2011; Zander 1992), and it is available in washes (Choi 2010), creams (Zheng 2013), and lotions (Babayeva 2011). Chemical peel of salicylic acid at a concentration of 20% to 30% is also available and useful in acne treatment (Bae 2013). Salicylic acid monotherapy (Strauss 2007), or combination therapy with benzoyl peroxide (Akarsu 2012; Seidler 2010), or clindamycin phosphate (NilFroushzadeh 2009; Touitou 2008) can improve acne lesions. Salicylic acid 20% or 30% peels (Kempiak 2008), or salicylic 20%/mandelic acid 10% peels (Garg 2009) are also effective for the treatment of acne vulgaris. Previous studies have shown that topical salicylic acid has mild to moderate activity against both non‐inflammatory lesions and inflammatory lesions in acne vulgaris (Akarsu 2012; Degitz 2008; Thiboutot 2009). It is approved for use in children with acne (Akhavan 2003).

Salicylic acid can break down the follicular keratotic plugs through dissolving the intercellular cement holding the stratum corneum cells and promoting the desquamation of follicular epithelium (Akarsu 2012; Akhavan 2003). It also has anti‐inflammatory capabilities, affecting the arachidonic acid cascade (Lee 2003).

When used at concentrations of 2% or higher, salicylic acid can cause local skin peeling and discomfort to some degree (Akarsu 2012; Boutli 2003). Salicylic acid is a FDA pregnancy category C drug (Kempiak 2008). There are no studies conducted in lactating women on topical use of salicylic acid and little is known about the excretion of salicylic acid in breast milk. Therefore, physicians advise women during lactation to avoid the use of salicylate (Akhavan 2003; Bozzo 2011).

Topical nicotinamide

Nicotinamide serves as the active form of niacin, having anti‐inflammatory effects in acne (Shalita 1995). Twice‐daily application of 4% or 5% nicotinamide gel for eight weeks can lead to significant improvement of acne conditions (Khodaeiani 2013; Shalita 1995a). Researchers published the first study that assessed nicotinamide in 1995 and the data suggest that 4% nicotinamide gel has comparable efficacy to 1% clindamycin gel in the treatment of inflammatory acne vulgaris (Shalita 1995). Another study also supports the comparable efficacy of 4% nicotinamide gel to 1% clindamycin gel in moderate inflammatory acne vulgaris (Khodaeiani 2013). When used at a concentration of 5%, nicotinamide gel is as effective as clindamycin 2% gel for the treatment of mild to moderate acne vulgaris (Shahmoradi 2013). Nicotinamide 4% linoleic acid‐rich phosphatidylcholine produced global clinical improvements in acne (Morganti 2011).

The mechanisms of action are mainly due to its potent anti‐inflammatory effect (Shalita 1995a), and inhibition of sebum production (Draelos 2006a). Nicotinamide exerts its anti‐inflammatory effects by inhibiting C acnes‐induced chemokine IL‐8 production in keratinocytes through interfering with NF‐kappa B by inhibiting PARP‐1 and mitogen‐activated protein kinases (MAPK) pathways (Grange 2009).

Only mild stinging or burning at the application site is reported during topical use of nicotinamide (Shalita 1995a). It is safe for women in pregnancy, although the FDA pregnancy category rating of topical nicotinamide is not available (Rolfe 2014). Nicotinamide is excreted in breast milk, but no data regarding topical nicotinamide use in women who are pregnant or lactating are available (Rolfe 2014; Stockton 1990).

Topical sulphur

Sulphur is a yellow non‐metallic chemical element with antifungal, antibacterial, and keratolytic properties (Gupta 2004). The topical sulphur‐containing preparations at concentrations of 1% to 10% are helpful for acne treatment (Akhavan 2003), even though they may be both comedonal and comedolytic (Mills 1972). Sulphur is available in the form of lotions, foam, creams, ointments, and soaps. When used together with benzoyl peroxide or sodium sulphacetamide, sulphur shows a better therapeutic effect on acne vulgaris. For example, sodium sulphacetamide 10% with sulphur 5% emollient foam (Del Rosso 2009), sodium sulphacetamide with sulphur lotion (Breneman 1993), and benzoyl peroxide 10% plus sulphur in the range 2% to 5% cream (Danto 1966; Wilkinson 1966) are all effective acne treatments.

The mechanism of action may be due to sulphur's keratolytic action and consequent inhibitory effect on the proliferation of C acnes (Gupta 2004). It is thought that sulphur interacts with cysteine in keratinocytes resulting in the production of hydrogen sulphide, which has a keratolytic effect by rupturing the disulphide bonds of cysteine molecules in keratin (Pace 1965).

Adverse events are rare during topical use of sulphur. Commonly reported adverse effects include dryness and itching of the skin (Breneman 1993; Gupta 2004; Tarimci 1997). Sulphur is a FDA pregnancy category C drug (Akhavan 2003). Little is known about the excretion of sulphur in breast milk. Therefore, caution should be used by breastfeeding mothers (Akhavan 2003).

Topical zinc

Zinc is known as an essential trace element (Sharquie 2008). It has antimicrobial as well as anti‐inflammatory actions and it is useful for many dermatological problems (Habbema 1989; Sharquie 2007; Sharquie 2008). Physicians often use zinc plus antibiotic combination products for acne treatment (Cunliffe 2005; Habbema 1989). For example, researchers used the form of erythromycin (4%) plus zinc (1.2%) and clindamycin (1%) plus zinc (0.52%), which can be applied twice‐daily for 12 weeks or more (Cunliffe 2005; Habbema 1989). Previous studies have documented that the combination of zinc with antibiotics is more advantageous to acne patients than antibiotics alone (Cunliffe 2005a; Habbema 1989). Some reports suggest that zinc acetate contributes most to the antimicrobial action of an erythromycin/zinc combination (Fluhr 1999). When used alone, topical zinc is also useful for acne patients. Recently, zinc sulphate solution has been showed to be effective in the treatment of acne vulgaris, though it may be less effective than tea lotion (Sharquie 2008).

The mechanism of action may be due to zinc's antimicrobial, anti‐inflammatory, and other actions (Fluhr 1999; Sharquie 2008). Several reports have documented the anti‐propionibacterial activity of zinc in vitro (Bojar 1994; Fluhr 1999). The efficacy on inflammatory lesions by zinc suggests the importance of its anti‐inflammatory actions on acne treatment (Dreno 1989).

There are no important adverse effects reported during topical use of zinc (Cunliffe 2005; Sharquie 2008). The adverse effects include burning sensation and itching, but they are always mild and transient (Sharquie 2008). Although the FDA pregnancy category rating of topical zinc is not available, oral zinc sulphate is a pregnancy category C drug (Chien 2016).

Topical fruit acid (alpha‐hydroxy acid)

Alpha‐hydroxy acid (or fruit acid) refers to a special group of organic acids that can be found in natural foods (Hunt 1992). It is useful in a variety of dermatological conditions with abnormal keratinisation (Hunt 1992; Sharad 2013). Glycolic acid belongs to alpha‐hydroxy acids, which can be used for chemical peeling at concentrations ranging from 20% to 70% (Sharad 2013). Glycolic acid peel is the most common fruit peel (Sharad 2013). In Asian acne patients, the use of 50% glycolic acid peels once in three weeks for 10 weeks can result in significant resolution of comedones, papules, and pustules (Wang 1997). Another study also suggests the efficacy of glycolic acid peels (20% to 70%) in the reduction of both non‐inflamed and inflamed lesions when applied twice every four weeks for six months (Ilknur 2010). Moreover, they are also useful in nodule‐cystic acne and acne scars (Atzori 1999; Wang 1997). Therefore, glycolic acid peel is a useful alternative treatment for acne (Sharad 2013). In addition to glycolic acid, gluconolactone (14%), another alpha‐hydroxy acid, has showed a significant therapeutic effect in reducing acne lesions (Hunt 1992).

The mechanism of action may be due to the modification of keratinisation by alpha‐hydroxy acids, and the anti‐inflammatory activity of alpha‐hydroxy acids may also play a role in acne improvement (Hunt 1992).

The adverse effects are always minimal during topical use of alpha‐hydroxy acids (Hunt 1992; Ilknur 2010), and patient tolerance is reported to be good (Sharad 2013). Glycolic acid is a pregnancy category N drug (rating is not available) but there are no published reports demonstrating any adverse effects during pregnancy (Chien 2016).

Why it is important to do this review

The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2010 and 2013 projects measured disease burden using disability‐adjusted life year (DALY) metrics (Hay 2014; Karimkhani 2017); of the 15 dermatologic conditions, acne vulgaris was the skin disease with the second highest percentage of total DALYs either in the GBD 2010 or GBD 2013 study (Hay 2014; Karimkhani 2017). Thus, the global burden of acne is very high (Hay 2014; Karimkhani 2017). A recent report, however, has demonstrated that the limited number of reviews and protocols published in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) does not reflect disease disability estimates for acne and that this topic is underrepresented (Karimkhani 2014). Cochrane Reviews on oral treatments including minocycline (Garner 2012) and contraceptive pills (Arowojolu 2012) for acne have been conducted. Topical treatments including retinoids, benzoyl peroxide (Yang 2014), and antibiotics for acne are (or will be) dealt with in other Cochrane Reviews.

We know of several reviews on some of these topical treatments for acne (Gamble 2012; Haider 2004; Lehmann 2001; Purdy 2011; Seidler 2010). Three of these reviews demonstrated that use of topical azelaic acid shows benefits for mild and moderate acne and is comparable to topical retinoid or benzoyl peroxide (Gamble 2012; Haider 2004; Purdy 2011). However, there is only limited evidence to demonstrate that topical salicylic acid (Gamble 2012), nicotinamide (Purdy 2011), sulphur (Gamble 2012; Lehmann 2001), zinc (Gamble 2012), and alpha‐hydroxy acid (Sharad 2013) may be beneficial for acne treatment. A review on salicylic acid did not include adequate intervention arms and did not assess side effects of the treatments (Seidler 2010). In summary, most of the up to date evidence on these medications is from summary reviews (Gamble 2012; Haider 2004; Purdy 2011; Sharad 2013), and the only two systematic reviews identified are either out of date (Lehmann 2001), or without clear assessment of the quality of evidence (Seidler 2010).

Given the various limitations of previous reviews and the new evidence from recent studies on the use of azelaic and salicylic acids, nicotinamide, sulphur, zinc, and alpha‐hydroxy acid, we feel it is important to systematically assess their benefits and harms for the treatment of acne vulgaris using Cochrane methodology.

The plans for this review were published as a protocol with a slightly different title, 'Topical azelaic acid, salicylic acid, nicotinamide, and sulphur for acne' (Liu 2014).

Objectives

To assess the effects of topical treatments (azelaic acid, salicylic acid, nicotinamide, zinc, alpha‐hydroxy acid, and sulphur) for acne.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

Randomised trials with a cross‐over design were eligible. We excluded cluster‐RCTs and quasi‐RCTs trials (e.g. trials that allocate by using date of birth, case record number, or alternation).

Types of participants

We included participants with acne vulgaris who have been diagnosed based on clinical definition, regardless of age, gender, acne severity, and previous treatments. Studies were also eligible where participants were diagnosed as having papulopustular, inflammatory, juvenile, or polymorphic acne.

We excluded trials in which participants had a diagnosis of other forms of acne variants or acneiform eruptions, as listed in Table 12.

Types of interventions

Topical azelaic acid, topical salicylic acid, topical nicotinamide, topical sulphur, topical zinc, and topical fruit acid (alpha‐hydroxy acid) with any treatment regimen, duration, dose, and delivery mode, compared with:

other topical treatments;

placebo;

no treatment.

The trials that compared the intervention treatments with each other were eligible for inclusion. The concomitant use of other topical or oral medications for acne vulgaris had to be the same in both intervention arms.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Participants' global self‐assessment of acne improvement (e.g. measured by a 4‐point scale: excellent, good, fair, and poor)

Withdrawal for any reason

Secondary outcomes

Change in lesion counts (total, or inflamed and non‐inflamed separately)

Physicians' global evaluation of acne improvement

Minor adverse events (assessed as the total number of participants who experienced at least 1 minor adverse event)

Quality of life

Timing

We assessed treatment efficacy by grouping the outcomes into short‐term treatment (less than or equal to 4 weeks), medium‐term treatment (from 5 to 8 weeks) and long‐term treatment (more than 8 weeks). Where there was more than one follow‐up point within the same time period, we used the longest one.

Search methods for identification of studies

We aimed to identify all relevant RCTs regardless of language or publication status (published, unpublished, in press, or in progress).

Electronic searches

The Cochrane Skin Information Specialist searched the following databases up to 1 May 2019.

Cochrane Skin Group Specialised Register using the search strategy in Appendix 1

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2019, Issue 5) in the Cochrane Library using the search strategy in Appendix 2.

MEDLINE via Ovid (from 1946) using the strategy in Appendix 3.

Embase via OVID (from 1974) using the strategy in Appendix 4.

LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Health Science Information database, from 1982) using the strategy in Appendix 5.

Trials registers

We (HL and HY) searched the following trials registers up to 1 May 2019 using the search terms (azelaic acid, salicylic acid, o‐hydroxybenzoic acid, nicotinamide, niacinamide, sulphur, sulfur, zinc, fruit acid, alpha‐hydroxy acid, and glycolic acid) combined with health condition 'acne'.

ISRCTN registry (www.isrctn.com).

ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov).

Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (www.anzctr.org.au).

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (apps.who.int/trialsearch).

EU Clinical Trials Register (www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu).

Searching other resources

References from included studies

We checked the bibliographies of included studies for further references to relevant trials.

Adverse effects

We did not perform a separate search for adverse events of the target interventions. However, we examined data on adverse effects from the included studies we identified if present.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (HL and HY) independently inspected the titles and abstracts of all studies identified for eligibility. For studies that appeared to be eligible, we retrieved the full text of reports for reassessment to see whether they met the inclusion criteria. We resolved discrepancies by discussion between review authors (HL and HY) and, if necessary, input by a third review author (JX or HS).

Data extraction and management

For data collection, we used a data extraction form adapted from a standard one and the form was piloted followed by minor revisions. We extracted data on an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) basis and used Review Manager 5 for the analysis of data (Review Manager 2014).

Two review authors (HL and HY) independently extracted data from eligible studies using an ITT approach and one review author (FP) extracted data from studies published in German. We collected both qualitative and quantitative information according to Table 7.3.a, 'Checklist of items to consider in data collection or data extraction', in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), and we collected characteristics of the included studies in sufficient detail to populate a table of 'Characteristics of included studies'. Where further information was required, we contacted the authors for clarification. We resolved any disagreements by discussion and, if necessary, involved a third review author (JX or HS). In the case of data displayed only in graphs or figures, if we were unable to contact study authors, we extracted the data manually using a ruler but only included the data if two review authors independently collected the same results.

The review authors were not blinded to journals, authors, or their academic affiliations. HL, HS and HY entered the data into the Review Manager 5 software (Review Manager 2014).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two authors (HL and HS) independently assessed the methodological quality of eligible studies using the 'Risk of bias' tool, as outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We resolved any disagreements by discussion and, if necessary, involved a third review author (JX or GL). We assessed the following domains for bias.

Random sequence generation (selection bias).

Allocation concealment (selection bias).

Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias).

Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias).

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias).

Selective reporting (reporting bias).

Other bias.

We categorised the risk of bias in each domain as either 'low', 'high', or 'unclear'. Where two or more out of seven domains within a trial were rated as 'high' risk of bias, we considered including the trial in a sensitivity analysis.

Measures of treatment effect

Interpretation

If possible, we compared the pooled estimates with the minimally important difference (MID) values for both primary and secondary outcomes to aid interpretation. We used the suggested MID from the literature, such as MID estimates for acne lesion counts (Gerlinger 2011), and Acne‐Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire (Acne‐QoL) outcomes (McLeod 2003).

Dichotomous data

For binary outcomes, we calculated the risk ratio (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI) to summarise estimates of treatment effect, because the RR was more intuitive than the odds ratio (OR) (Boissel 1999), which was often misinterpreted as RR by clinicians (Deeks 2002).

Continuous data

Summary statistic

For continuous outcomes, we calculated the mean difference (MD) and its 95% CI to summarise data, and used standardised mean difference (SMD) with 95% CI where different measurement scales had been used across studies.

Skewed data

Data from continuous outcomes were often not normally distributed and statistics to summarise average (medians) and spread of data (quartiles, minimum and maximum, and ranges) were used in this case. We summarised such variables using the summary statistics for skewed data in additional tables rather than in the main analysis, and we did not analyse the treatment effect sizes to avoid applying parametric tests to data with skewed distribution. We classified data as skewed when the mean was less than twice the standard deviation (SD), but only when the data were from a scale or outcome measure that had positive values with a minimum value of zero (Altman 1996). Sometimes trials used means to summarise skewed data from very large trials. In this situation, we entered the data into analysis but a sensitivity analysis was necessary.

Ordinal data

Results of participant and doctor evaluations may be presented as short ordinal data. In this situation, we converted this type of data into dichotomous data (e.g. 'improved' or 'not improved'), and we conducted a sensitivity analysis using different cut off points (e.g. 'greatly improved' or 'not greatly improved'). We treated long ordinal data as continuous data.

Unit of analysis issues