During a patient’s intensive care unit (ICU) admission, caregivers (e.g., family members) often experience intense stress. Possible stressors include the patient’s critical medical condition, threat of possible death, exposure to frightening sights and sounds associated with intensive care, and medical decision-making on the patient’s behalf. Given the potentially traumatic nature of these stressors, a subset of caregivers experiences significant psychological distress, with some (e.g., 21–30%) (1, 2) developing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after the patient’s ICU admission. Despite increasing clinical interest in caregivers’ mental health, ICU-based interventions have not resulted in meaningful reductions in PTSD (3–6). Interventions may be more efficacious with increased attention to caregivers’ peritraumatic psychological reactions (i.e., emotional responses during or immediately after these stressors).

Caregivers’ peritraumatic distress and dissociation during ICU admissions, including acute helplessness, derealization, and numbness (7, 8), may influence their post-ICU adjustment. Indeed, peritraumatic distress and dissociation enhance risk for PTSD in other contexts (9–12). Yet, research addressing these reactions in ICU settings is extremely limited (1). Prior studies have had a greater focus on static pretrauma factors (e.g., demographics) and post-trauma symptoms (13), overlooking the peritraumatic period. In this study, we investigated the frequency of peritraumatic stress symptoms and their correlates among caregivers of patients admitted to the ICU.

Methods

Caregivers at the bedside of medical ICU patients were recruited between June 2016 and January 2019. This sample includes caregivers (n = 138) who completed a one-time self-report survey of their own emotional reactions that was added to a larger study on patient dyspnea; of these, 58 caregivers also completed a demographic survey that was later added. Data were also collected from patients, nurses, and medical charts (14). Institutional review board approval and informed consent were obtained.

Measures

Peritraumatic distress and dissociation symptoms.

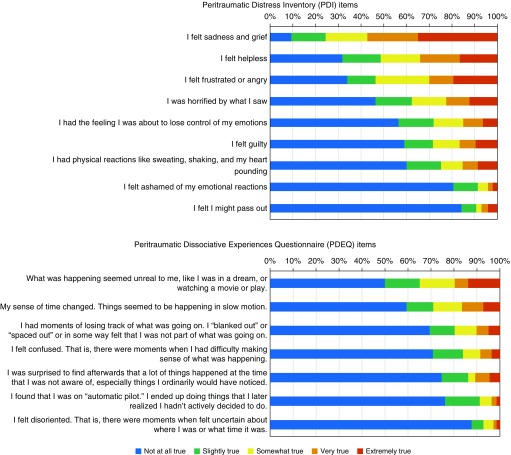

Nine items from the Peritraumatic Distress Inventory (PDI) (7) and seven items from the Peritraumatic Dissociative Experiences Questionnaire (PDEQ) (8) were administered (Figure 1). Questionnaires were abbreviated to limit subject burden. Item response options ranged from “not at all true” (scored as 1) to “extremely true” (scored as 5). Total scores on each scale were computed, with higher scores indicating greater peritraumatic stress symptoms. Cronbach’s α-values were acceptable for the PDI (0.85) and PDEQ (0.82); total scores ranged from 9 to 45 and 7 to 34, respectively.

Figure 1.

Frequency of endorsement of peritraumatic stress symptoms among caregivers of intensive care unit patients. Note: Items are from the Peritraumatic Distress Inventory (PDI [7]) and the Peritraumatic Dissociative Experiences Questionnaire (PDEQ [8]). A subset of full PDEQ and PDI items was administered to limit participant burden.

Caregiver characteristics.

Caregivers reported their age, sex, years of education, race, and ethnicity. Demographic characteristics were only available for a subset of caregivers (n = 58) because the parent study focused on patients.

Patient characteristics.

Patient age, sex, race, ethnicity, length of ICU stay before the assessment, and whether the patient died in the ICU within the next month were collected from medical charts. Trained researchers assessed patients’ communication status and use of mechanical ventilation on the day of the caregiver assessment. Caregivers completed proxy reports of patient symptoms, including pain, weakness, and nausea in the past two days; the total number of endorsed symptoms indicated symptom burden.

Analytic approach

Descriptive statistics were computed. Nonparametric analyses (Spearman correlations, Mann-Whitney U tests, and Kruskal-Wallis tests) tested whether caregivers’ PDI and PDEQ scores varied according to patient and caregiver characteristics; these factors were selected on the basis of prior literature suggesting possible associations with caregiver distress (13, 15–17). To inform future research, ancillary adjusted analyses were conducted by including all of the examined patient characteristics (see Table 1) as predictors of PDI and PDEQ scores to examine their associations with peritraumatic stress while adjusting for the other factors. Because caregiver characteristics were only available for a smaller subsample (n = 58), to preserve the sample size, these factors were not included in the adjusted models. Linear regression was used for adjusted analyses with PDI scores. Because PDEQ scores were not normally distributed, scores were dichotomized above and below the median PDEQ score (median, 9.5), and logistic regression was used.

Table 1.

Adjusted regression models predicting caregiver peritraumatic distress (Peritraumatic Distress Inventory scores) and dissociation (Peritraumatic Dissociative Experiences Questionnaire scores)

| Predictor | Linear Regression Outcome: PDI Scores |

Logistic Regression Outcome: Higher PDEQ Scores (above Median) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b-Value | SE | P Value | aOR | 95% CI | P Value | |

| Patient age (in yr) | −0.08 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.98 | 0.95 to 0.99 | 0.02 |

| Patient female (vs. male) | −2.48 | 1.45 | 0.09 | 0.57 | 0.24 to 1.35 | 0.20 |

| Patient of white race (vs. other) | −2.48 | 1.65 | 0.14 | 0.47 | 0.18 to 1.23 | 0.12 |

| Patient of Hispanic/Latino ethnicity (vs. other) | 2.02 | 2.01 | 0.32 | 1.65 | 0.50 to 5.47 | 0.41 |

| Patient symptom burden (caregiver rated) | 1.72 | 0.39 | <0.001 | 1.17 | 0.93 to 1.48 | 0.18 |

| Patient able to communicate (vs. unable) | −0.57 | 1.79 | 0.75 | 0.60 | 0.21 to 1.74 | 0.35 |

| Patient using mechanical ventilation (vs. not using) | 1.38 | 1.90 | 0.47 | 0.73 | 0.24 to 2.26 | 0.58 |

| Patient died in ICU within 1 mo (vs. did not) | −0.67 | 1.65 | 0.68 | 0.90 | 0.34 to 2.37 | 0.83 |

| ICU length of stay (in d) | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 1.04 | 0.97 to 1.11 | 0.31 |

Definition of abbreviations: aOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; ICU = intensive care unit; PDEQ = Peritraumatic Dissociative Experiences Questionnaire; PDI = Peritraumatic Distress Inventory; SE = standard error.

Models included patient age, symptom burden, and ICU length of stay as continuous variables and other factors as binary variables. b-value is the unstandardized regression coefficient. Bold values indicate statistically significant, P < 0.05.

Results

Table 2 summarizes caregiver and patient characteristics. Figure 1 summarizes frequencies of peritraumatic distress (median, 18; interquartile range [IQR], 10.5) and dissociation (median, 9.5; IQR, 7) symptoms. PDI items endorsed most frequently as “very true” or “extremely true” included sadness and grief (57%), helplessness (34%), and frustration and anger (30%). On the PDEQ, caregivers most frequently reported feeling that events seemed unreal (20%) and as if they were happening in slow motion (17%).

Table 2.

Characteristics of caregivers (n = 138) and patients (n = 138) in subsample

| Characteristics | No. with Data | Mean (SD) or n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Caregivers | ||

| PDEQ score | 138 | 11.5 (5.4) |

| PDI score | 138 | 19.7 (8.0) |

| Age, yr | 58 | 55.8 (15.4) |

| Sex | 58 | |

| Male | 19 (33) | |

| Female | 39 (67) | |

| Race | 57 | |

| White | 38 (67) | |

| Black | 5 (9) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 4 (7) | |

| Bi- or multiracial | 3 (5) | |

| Other/unspecified | 7 (12) | |

| Ethnicity | 57 | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 9 (16) | |

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 48 (84) | |

| Education, yr | 56 | 16.8 (4.7) |

| Patients | ||

| Age, yr | 138 | 64.4 (18.1) |

| Sex | 138 | |

| Male | 87 (63) | |

| Female | 51 (37) | |

| Race | 127 | |

| White | 99 (78) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 15 (12) | |

| Black | 12 (9) | |

| Bi- or multiracial | 1 (1) | |

| Ethnicity | 134 | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 21 (16) | |

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 113 (84) | |

| Length of ICU admission, d | 138 | 6.1 (8.6) |

| Able to communicate | 134 | 43 (32) |

| Using mechanical ventilator | 131 | 102 (78) |

| Died in ICU within 1 mo | 138 | 36 (26) |

Definition of abbreviations: ICU = intensive care unit; PDEQ = Peritraumatic Dissociative Experiences Questionnaire; PDI = Peritraumatic Distress Inventory; SD = standard deviation.

Percent data indicate percentages of those with available data for each variable.

Caregivers of younger patients reported greater peritraumatic distress (ρ = −0.24; P = 0.005; n = 138) and dissociation (ρ = −0.26; P = 0.002; n = 138) than caregivers of older patients. Patient sex, race, and ethnicity were not significantly associated with caregivers’ peritraumatic symptoms (P > 0.11 for all comparisons). The patient’s length of ICU stay was associated with caregiver peritraumatic distress (ρ = 0.26; P = 0.002; n = 138) and dissociation (ρ = 0.20; P = 0.02; n = 138); longer admissions were associated with greater peritraumatic symptoms. Caregivers who reported greater symptom burden for the patient had higher peritraumatic distress (ρ = 0.31; P < 0.001; n = 135) and dissociation (ρ = 0.18; P = 0.03; n = 135). Dissociation symptoms were higher among caregivers of patients who could not communicate (median, 10; IQR, 7), than among those who could communicate (median, 8; IQR, 5; U = 1,447; P = 0.01; n = 134); peritraumatic distress showed a similar pattern (median, 18; IQR, 12; vs. median, 17; IQR, 9, respectively; U = 1,632; P = 0.12; n = 134). Peritraumatic stress symptoms did not differ significantly between caregivers of patients who were using mechanical ventilation and those who were not or between those who later died in the ICU within 1 month and those who did not (P > 0.44 for all comparisons). PDI and PDEQ scores were not significantly related to caregiver age, sex, education, race, or ethnicity (P > 0.14 for all comparisons).

Ancillary adjusted analyses are summarized in Table 1. The set of predictors explained 23% of the variance in PDI scores (R2 = 0.23; F[9,105] = 3.54; P = 0.001). Younger patient age (regression coefficient b = −0.08; standard error [SE], 0.04; P = 0.03) and greater symptom burden (regression coefficient b = 1.72; SE = 0.39; P < 0.001) remained significant predictors of PDI scores in the adjusted model. The set of predictors did not significantly improve the logistic regression model predicting high versus low PDEQ scores (P = 0.15), but caregivers of older patients were less likely to have PDEQ symptoms above the median (adjusted odds ratio per year of increasing patient age, 0.98; 95% confidence interval, 0.95 to 0.99; P = 0.02).

Discussion

In this study, a subset of caregivers reported peritraumatic distress and dissociation during patients’ ICU admissions. These results suggest that peritraumatic stress symptoms are common in this setting; severity was associated with younger patient age and greater symptom burden. Given other research suggesting that these symptoms can heighten risk for PTSD onset, peritraumatic stress symptoms warrant further study and attention in interventions that aim to reduce ICU caregiver distress.

These results have implications for optimizing interventions to reduce acute stress reactions (and possibly later PTSD) in ICU caregivers. For example, peritraumatic symptoms may limit engagement in behavioral interventions initiated during acute care (18). This may help to explain why prior ICU interventions had limited efficacy for reducing PTSD symptoms. ICU-based interventions that account for or directly target peritraumatic stress symptoms may hold promise for those most likely to need them (19). Based on research in other disciplines (20–24), psychological interventions that enhance caregivers’ coping skills for overwhelming emotions, target at-risk caregivers for standard PTSD treatment in the early post-ICU period, and/or use pharmacotherapies to mitigate autonomic dysregulation might have promise in caregivers of critically ill patients. However, this literature is nascent in critical care settings, and meta-analyses of early treatments to prevent PTSD are inconclusive, suggesting additional research is needed (20, 22, 25). Our research group is currently pilot testing an intervention to target peritraumatic distress among surrogate decision makers in the ICU, which includes exercises such as grounding and distress tolerance in short modules to maximize feasibility of delivery (19).

Because interventions targeting all ICU caregivers are not indicated (20, 26), future research is needed to identify which caregivers are at greater risk and may benefit from intervention (27). In the present study, we provide descriptive data and correlates of peritraumatic distress and dissociation, which are notable risk factors for PTSD in other populations but are understudied in ICU settings. These symptoms may be important to consider in research design and clinical efforts to enhance ICU caregivers’ well-being. There are also limitations. Demographic information was only available for a subset of caregivers; because of the parent study’s focus on patients, caregiver surveys were expanded partway through the study. This limited our ability to detect whether peritraumatic stress varied by caregivers’ characteristics. We could not determine causal links between patient- or caregiver-related factors and peritraumatic stress in this cross-sectional study, and future studies are needed to determine whether these factors (e.g., symptom burden) impact caregivers’ peritraumatic stress over time. Given that this study was cross-sectional and did not include a PTSD diagnostic assessment, we could not test whether ICU caregivers with greater peritraumatic stress symptoms had elevated risk for PTSD onset in the post-ICU period. Although longitudinal research should examine how peritraumatic factors relate to PTSD among ICU caregivers specifically, it may be appropriate to screen individuals for peritraumatic reactions to refine recruitment in intervention trials. In summary, greater research attention to peritraumatic stress symptoms may help to address prior barriers to effective interventions for caregivers of ICU patients.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supported by the National Cancer Institute (grants R35CA197730 and R21CA218313), the National Institute on Aging (grant T32AG049666), and the National Institute of Nursing Research (grant R21NR018693).

Author Contributions: H.M.D.: Substantial contribution to analysis and interpretation of data and drafted and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. L.L.: Substantial contribution to acquisition and interpretation of data and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. E.J.S.: Substantial contribution to interpretation of data and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. D.A.B.: Substantial contribution to acquisition and interpretation of data and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. H.G.P.: Substantial contribution to acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data and drafted and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. Each author approved the final version of the manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this letter at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.de Miranda S, Pochard F, Chaize M, Megarbane B, Cuvelier A, Bele N, et al. Postintensive care unit psychological burden in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and informal caregivers: a multicenter study. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:112–118. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181feb824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van den Born-van Zanten SA, Dongelmans DA, Dettling-Ihnenfeldt D, Vink R, van der Schaaf M. Caregiver strain and posttraumatic stress symptoms of informal caregivers of intensive care unit survivors. Rehabil Psychol. 2016;61:173–178. doi: 10.1037/rep0000081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.White DB, Angus DC, Shields AM, Buddadhumaruk P, Pidro C, Paner C, et al. PARTNER Investigators. A randomized trial of a family-support intervention in intensive care units. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2365–2375. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1802637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carson SS, Cox CE, Wallenstein S, Hanson LC, Danis M, Tulsky JA, et al. Effect of palliative care-led meetings for families of patients with chronic critical illness: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;316:51–62. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.8474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cox CE, White DB, Hough CL, Jones DM, Kahn JM, Olsen MK, et al. Effects of a personalized web-based decision aid for surrogate decision makers of patients with prolonged mechanical ventilation: a randomized clinical trial. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170:285–297. doi: 10.7326/M18-2335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garrouste-Orgeas M, Flahault C, Vinatier I, Rigaud JP, Thieulot-Rolin N, Mercier E, et al. Effect of an ICU diary on posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms among patients receiving mechanical ventilation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;322:229–239. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.9058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brunet A, Weiss DS, Metzler TJ, Best SR, Neylan TC, Rogers C, et al. The Peritraumatic Distress Inventory: a proposed measure of PTSD criterion A2. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1480–1485. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.9.1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marmar CR, Weiss DS, Metzler TJ. The Peritraumatic Dissociative Experiences Questionnaire. In: Wilson JP, Keane TM, editors. Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD. New York: Guilford Press; 1997. pp. 144–168. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ozer EJ, Best SR, Lipsey TL, Weiss DS. Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and symptoms in adults: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2003;129:52–73. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trickey D, Siddaway AP, Meiser-Stedman R, Serpell L, Field AP. A meta-analysis of risk factors for post-traumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents. Clin Psychol Rev. 2012;32:122–138. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shalev AY, Peri T, Canetti L, Schreiber S. Predictors of PTSD in injured trauma survivors: a prospective study. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:219–225. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brewin CR, Andrews B, Valentine JD. Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:748–766. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.5.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson CC, Suchyta MR, Darowski ES, Collar EM, Kiehl AL, Van J, et al. Psychological sequelae in family caregivers of critically ill intensive care unit patients: a systematic review. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2019;16:894–909. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201808-540SR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gentzler ER, Derry H, Ouyang DJ, Lief L, Berlin DA, Xu CJ, et al. Underdetection and undertreatment of dyspnea in critically ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199:1377–1384. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201805-0996OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haines KJ, Denehy L, Skinner EH, Warrillow S, Berney S. Psychosocial outcomes in informal caregivers of the critically ill: a systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:1112–1120. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee RY, Engelberg RA, Curtis JR, Hough CL, Kross EK. Novel risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in family members of acute respiratory distress syndrome survivors. Crit Care Med. 2019;47:934–941. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chaudhry D, Jain N, Singh A, Sethi S, Virdi S. Incidence and predictors of anxiety and depression in caregivers of critically ill patients and comparison of these symptoms at the time of admission and discharge from the intensive care unit (ICU): a prospective study [abstract] Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193:A4737. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Price M, Kearns M, Houry D, Rothbaum BO. Emergency department predictors of posttraumatic stress reduction for trauma-exposed individuals with and without an early intervention. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2014;82:336–341. doi: 10.1037/a0035537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prigerson HG, Viola M, Brewin CR, Cox C, Ouyang D, Rogers M, et al. Enhancing & Mobilizing the POtential for Wellness & Emotional Resilience (EMPOWER) among surrogate decision-makers of ICU patients: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2019;20:408. doi: 10.1186/s13063-019-3515-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qi W, Gevonden M, Shalev A. Prevention of post-traumatic stress disorder after trauma: current evidence and future directions. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2016;18:20. doi: 10.1007/s11920-015-0655-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shalev AY, Ankri Y, Gilad M, Israeli-Shalev Y, Adessky R, Qian M, et al. Long-term outcome of early interventions to prevent posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77:e580–e587. doi: 10.4088/JCP.15m09932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sijbrandij M, Kleiboer A, Bisson JI, Barbui C, Cuijpers P. Pharmacological prevention of post-traumatic stress disorder and acute stress disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2:413–421. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00121-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meli L, Chang BP, Shimbo D, Swan BW, Edmondson D, Sumner JA. Beta blocker administration during emergency department evaluation for acute coronary syndrome is associated with lower posttraumatic stress symptoms 1-month later. J Trauma Stress. 2017;30:313–317. doi: 10.1002/jts.22195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pacella ML, Irish L, Ostrowski SA, Sledjeski E, Ciesla JA, Fallon W, et al. Avoidant coping as a mediator between peritraumatic dissociation and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms. J Trauma Stress. 2011;24:317–325. doi: 10.1002/jts.20641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Birk JL, Sumner JA, Haerizadeh M, Heyman-Kantor R, Falzon L, Gonzalez C, et al. Early interventions to prevent posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in survivors of life-threatening medical events: a systematic review. J Anxiety Disord. 2019;64:24–39. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2019.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roberts NP, Kitchiner NJ, Kenardy J, Bisson JI. Early psychological interventions to treat acute traumatic stress symptoms. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(3):CD007944. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007944.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rose L, Muttalib F, Adhikari NKJ. Psychological consequences of admission to the ICU: helping patients and families. JAMA. 2019;322:213–215. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.9059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.