To the Editor,

Since Covid-19 outbreak in March 2020, concerns have risen about how to perform ventilation during cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), balancing the need for victim to be resuscitated according to the best evidence with rescuers safety. Indeed, SARS-Cov-2 virus has shown to be highly transmissible via aerosol droplets generated from the airways of an infected person, both symptomatic and not.1 While for occasional rescuers (i.e. laypeople), chest compression-only (CCO) CPR can be recommended as an alternative to compressions-ventilations technique,2 reasonable suggestions for healthcare professionals are lacking.

So far, safety focus for personnel with a duty to respond has been placed on high-level personal protection equipment (PPE) rather than on a method to minimize dispersion of exhaled gases from the patient. Endotracheal intubation (ETI) is still considered the best way to isolate airways provided that it is performed by a high-skilled operator, possibly with a video laryngoscope aid.3

Recently, an American interim guidance for basic and advanced life support has been published suggesting questionable approaches to obtain oxygenation of the patient in cardiac arrest prior ETI.4 It is unlikely that both ventilation with a tight seal bag-mask device or passive oxygenation with an oxygen high flow facial mask can effectively constrain exhalation and limit rescuers exposition to patient-generated droplets during CPR.

In order to stimulate discussion on this crucial aspect of CPR, we propose a feasible modification of ventilation through a supraglottic airway (i-gel®, Intersurgical). I-gel is a device widely used among professional rescuers since its easy insertion and effectiveness in providing ventilation during CPR.5, 6

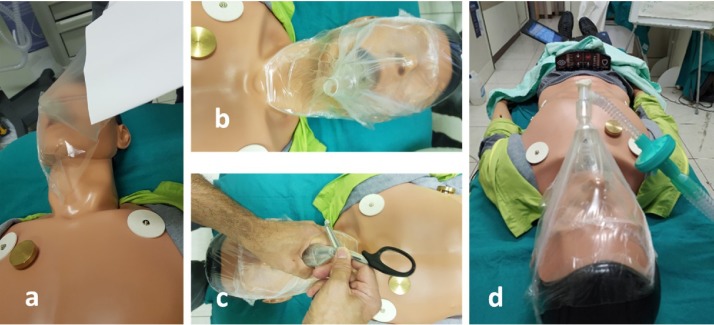

We tested the modified procedure on an ALS mannequin with a ventilation feedback system (Man Advanced®, Ambu). After i-gel insertion and before any ventilation attempt to check for proper position, we applied a first large square-shaped sheet of adhesive transparent drape from one chick to the opposite, wrapping in the external portion of the i-gel. A second similar sheet was applied from the forehead to the chin, over the first one (Fig. 1 a and b). After checking for good drape seal on the whole mannequin face, we perforated the drape onto the i-gel connector and attached a HEPA filter before a self-inflating bag (Fig. 1c and d). Proper device position was then checked through chest rising. To detect any minor inspiratory leak (overpressure phase) around the drape perimeter, we attached the device to a ventilator (Servo-air®, Getinge) setting a tidal volume of 600 ml with a rate of 10 breath per minute and a PEEP of 5 cmH20 to allow circuit washout. The circuit was able to provide exactly the set tidal volume with no obvious inspiratory leak evidence as measured by the mannequin feedback system. To confirm this result, we are planning to test the system on a more realistic model.

Fig. 1.

Application of drapes and connection to circuit: (a) first drape; (b) second drape; (c) perforation of drapes; (c) connection.

If complete seal will be confirmed, this easy and low-coast adjunct could allow professional rescuers to provide effective ventilation during CPR trough a supraglottic device with no exposition to patient direct exhaled gases.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Tang B., Wang X., Li Q. Estimation of the transmission risk of the 2019-nCoV and its implication for public health interventions. J Clin Med. 2020;9:462. doi: 10.3390/jcm9020462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kitamura T., Kiyohara K., Nishiyama C. Chest compression-only versus conventional cardiopulmonary resuscitation for bystander-witnessed out-of-hospital cardiac arrest of medical origin: a propensity score-matched cohort from 143,500 patients. Resuscitation. 2018;126:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2018.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cook T.M., El-Boghdadly K., McGuire B., McNarry A.F., Patel A., Higgs A. Consensus guidelines for managing the airway in patients with COVID-19: guidelines from the difficult airway society, the association of anaesthetists the intensive care society, the faculty of intensive care medicine and the royal college of anaesthetists. Anaesthesia. 2020 doi: 10.1111/anae.15054. DOI: 10.1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.AHA Interim Guidance, Edelson D.P., Sasson C. Interim guidance for basic and advanced life support in adults, children, and neonates with suspected or confirmed COVID-19: from the Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee and Get With the Guidelines ®-Resuscitation Adult and Pediatric Task Forces of the American Heart Association in Collaboration With the American Academy of Pediatrics, American Association for Respiratory Care, American College of Emergency Physicians, The Society of Critical Care Anesthesiologists, and American Society of Anesthesiologists: Supporting Organizations: American Association of Critical Care Nurses and National EMS Physicians. Circulation. 2020 doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047463. DOI: 10.1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soar J., Nolan J.P., Böttiger B.W. On behalf of the adult advanced life support section collaborators. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2015: Section 3. Adult advanced life support. Resuscitation. 2015;95:100–147. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leventis C., Chalkias A., Sampanis M.A. Emergency airway management by paramedics: comparison between standard endotracheal intubation, laryngeal mask airway, and I-gel. Eur J Emerg Med. 2014;21:371–373. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]