Abstract

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an emerging infectious disease that was first reported in Wuhan, People’s Republic of China, and has subsequently spread worldwide. Clinical information on patients who contracted severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection in the perioperative period is limited. Here, we report seven cases with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection in the perioperative period of lung resection. Retrospective analysis suggested that one patient had been infected with the SARS-CoV-2 infection before the surgery and the other six patients contracted the infection after the lung resection. Fever, lymphopenia, and ground-glass opacities revealed on computed tomography are the most common clinical manifestations of the patients who contracted COVID-19 after the lung resection. Pathologic studies of the specimens of these seven patients were performed. Pathologic examination of patient 1, who was infected with the SARS-CoV-2 infection before the surgery, revealed that apart from the tumor, there was a wide range of interstitial inflammation with plasma cell and macrophage infiltration. High density of macrophages and foam cells in the alveolar cavities, but no obvious proliferation of pneumocyte, was found. Three of seven patients died from COVID-19 pneumonia, suggesting lung resection surgery might be a risk factor for death in patients with COVID-19 in the perioperative period.

Keywords: 2019 Novel coronavirus disease, Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, Characteristics, Perioperative period, Lung resection

Introduction

As of March 5, 2020, there have been 80,565 cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) confirmed in the People’s Republic of China with 3015 deaths.1 As the confirmed cases are increasing, studies with a large sample size have provided detailed clinical information, including the clinical characteristics, laboratory and radiographic findings, and outcomes of COVID-19.2 Thus far, there has been one case report by Tian et al.3 who described the clinical course and pathologic findings of two cases infected with COVID-19 before lung lobectomy surgery. Nevertheless, there is still a lack of reports focusing on the cases of hospitalized patients infected with COVID-19 in the perioperative period, especially in patients who underwent lung resection surgery.

From January 1 to January 22, 2020, the period before human-to-human transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was declared by the national authority, the Thoracic Surgery Department of Tongji Hospital was on schedule to perform routine operations. A total of 139 patients underwent lung resection. Among these patients, seven cases were laboratory confirmed to be infected with SARS-CoV-2 after the lung resection. The confirmation of COVID-19 was on the basis of positive results of the patients’ oropharyngeal swabs tested for SARS-CoV-2 by real-time reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction assay.

In this report, we present the clinical characteristics and pathologic findings of patients diagnosed with COVID-19 in the perioperative period of lung resection and evaluate the influence of surgery on the progression of COVID-19.

Patient Details and Clinicopathologic Features

The seven patients were initially hospitalized for surgical treatment for lung tumor. The median age of the patients was 60 years (25th–75th percentile, 57–66 y), and five were men. The comorbidities included chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (in two patients), coronary atherosclerosis (three patients), interstitial lung disease (one patient), and hyperlipidemia (one patient). Six patients were diagnosed with NSCLC, and one patient was diagnosed with pulmonary sclerosing pneumocytoma. The surgeries were successfully performed in all cases without event, which included video-assisted thoracic surgery lobectomy (in four patients), video-assisted thoracic surgery segmentectomy plus wedge resection (in one patient), thoracotomy sleeve lobectomy (in one patient), and lobectomy plus bronchus reconstruction (in one patient). None of the patients had surgery-related postoperative complications, including air leak, hemorrhage, bronchopleural fistula, and arrhythmia (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Summary of Clinical Characteristics of the Seven Patients With COVID-19

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | Patient 6 | Patient 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 63 | 57 | 68 | 57 | 61 | 60 | 56 |

| Sex | Male | Male | Male | Male | Male | Female | Female |

| Smoking history | Current | Never | Ever | Current | Current | Never | Never |

| Resident of Wuhan | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Comorbidity | Interstitial lung disease | Coronary atherosclerosis | COPD | COPD | None | Hyperlipidemia + coronary atherosclerosis | Coronary atherosclerosis |

| FEV1 (L) | 2.5 | 3.07 | 1.39 | 2.36 | 2.42 | 2.04 | 2.77 |

| FEV1/FVC (%) | 70.01 | 75.11 | 58.52 | 65.09 | 83.32 | 85 | 72.51 |

| Tumor location | RLL | LLL | RLL | RUL | LUL | LUL (GGN) LLL (GGN) |

RLL |

| Tumor size (cm) | 3.5 | 5.0 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 3.5 | LUL: 1.0 LLL: 1.7 |

3.5 |

| Operation | RLL lobectomy | LLL lobectomy + S4 + 5 sleeve resection | RLL lobectomy + reconstruction of the right bronchus intermedius | RUL lobectomy | LUL lobectomy | LUL: wedge resection LLL: basal segmentectomy |

RLL lobectomy |

| Lymphadenectomy | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Approach | VATS | Open | Open | VATS | VATS | VATS | VATS |

| Duration of surgery (min) | 200 | 220 | 280 | 165 | 150 | 130 | 110 |

| Blood loss (mL) | 130 | 100 | 200 | 100 | 50 | 50 | 100 |

| Histologic type | SCC | Ade | Ade | Ade | Ade | LUL: Ade LLL: Ade |

PSP |

| Tumor stage | pT2aN0M0R0 | pT2N2M0R0 | pT1N2M0R0 | pT1bN0M0R0 | pT2N2M0R0 | LUL: T1aN0M0R0 LLL: T1bN0M0R0 |

NA |

Ade, adenocarcinoma; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC, forced vital capacity; GGN, ground-glass nodule; LLL, left lower lobe; LUL, left upper lobe; NA, not applicable; PSP, pulmonary sclerosing pneumocytoma; RLL, right lower lobe; RUL, right upper lobe; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; VATS, video-assisted thoracic surgery.

All seven patients presented with fever after the surgery; six had body temperature greater than 39°C. The time from surgery to onset of fever ranged from 0 days to 23 days (mean, 8.6 d). Accompanying symptoms included shortness of breath (in five patients), nonproductive cough (four patients), fatigue (two patients), productive cough (one patient), myalgia (two patients), and diarrhea (one patient) (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Onset Symptoms, Laboratory Findings, and Treatments of Seven Patients With COVID-19

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | Patient 6 | Patient 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | |||||||

| Fever | Yes (>39°C) | Yes (>39°C) | Yes (>39°C) | Yes (>39°C) | Yes (>39°C) | Yes (>38°C) | Yes (>39°C) |

| Short of breath | + | + | + | + | + | − | − |

| Dry cough | − | + | − | − | + | + | + |

| Productive cough | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Dyspnea | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Myalgia | + | − | − | − | + | − | − |

| Palpitation | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Fatigue | − | − | − | + | − | + | − |

| Diarrhea | − | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| Hospital stay before the operation (d) | 8 | 10 | 10 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 7 |

| Onset of symptoms (postop day) | 0 | 7 | 23 | 10 | 3 | 7 | 10 |

| Laboratory findings | |||||||

| First RT-PCR test for SARS-CoV-2 (postop day) | 4 | 15 | 34 | 13 | 12 | 12 | 15 |

| Positive RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2 (postop day) | 4 | 15 | 39 | 13 | 12 | 12 | 20 |

| Respiratory pathogensa | NA | NA | Positive IgM to CP and MP | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| Leukocyte, ×109/liter | 10.09 | 5.52 | 2.93 | 6.56 | 5.24 | 3.13 | 6.86 |

| Neutrophils, ×109/liter | 8.23 | 3.8 | 1.7 | 4.83 | 4.3 | 1.63 | 5.01 |

| Lymphocytes (initial, minimum), ×109/liter | I: 0.89 M: 0.18 |

I: 1.12 M: 0.47 |

I: 0.6 M: 0.29 |

I: 1.03 M: 0.68 |

I: 0.53 M: 0.39 |

I: 1.14 M: 1.03 |

I: 1.06 M: 0.26 |

| Monocytes, ×109/liter | 0.96 | 0.5 | 0.63 | 0.63 | 0.35 | 0.34 | 0.79 |

| Hemoglobin, g/liter | 128 | 122 | 120 | 135 | 117 | 106 | 125 |

| Platelet count, ×10⁹/liter | 227 | 225 | 148 | 220 | 188 | 191 | 210 |

| Procalcitonin, ng/mL | 0.22 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.05 |

| High-sensitivity C-reactive protein, mg/liter | 164.9 | 25.5 | 149 | 67.3 | 55.5 | 11.9 | 46.4 |

| Alanine transaminase | 13 | 196 | 18 | 38 | 31 | 27 | 13 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase | 31 | 186 | 28 | 23 | 47 | 42 | 17 |

| Total bilirubin, μmol/liter | 9.9 | 9.2 | 5.7 | 8.3 | 9.4 | 4.7 | 5 |

| Albumin, g/liter | 30.8 | 38 | 31.5 | 38.2 | 35 | 31.8 | 36.2 |

| Creatinine, μmol/liter | 70 | 54 | 50 | 63 | 54 | 61 | 49 |

| Prothrombin time, s | 12.7 | 12.1 | 12.3 | 14.8 | 13.5 | 13.4 | 13.7 |

| Activated partial thromboplastin time, s | 57.8 | 42.3 | 43.2 | 34.7 | 44.6 | 38.7 | 47.7 |

| D-dimers, μg/mL | 2.25 | 1.90 | 3.21 | 5.70 | 1.08 | 1.01 | 4.58 |

| Treatments | |||||||

| Intravenous antibiotics | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Antivirus therapy | Oseltamivir | Oseltamivir | Oseltamivir | Oseltamivir Lopinavir Ritonavir |

Oseltamivir Umifenovir |

Oseltamivir | Oseltamivir Umifenovir |

| Systemic corticosteroids | − | + | − | + | + | − | + |

| Intravenous immunoglobin | − | − | − | + | + | − | + |

| Oxygen therapy | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Mechanical ventilation | BiPAP | − | IMV | − | − | − | IMV |

| ECMO | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| ICU | + | − | + | − | − | − | + |

| Clinical outcomes | Died | Discharged | Died | In hospital | In hospital | Discharged | Died |

| Days since the onset of symptoms to the outcome event | 5 | 32 | 19 | NA | NA | 33 | 25 |

BiPAP, bilevel positive airway pressure; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; CP, Chlamydophila pneumoniae; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; I, initial; ICU, intensive care unit; IgM, immunoglobulin M; IMV, invasive mechanical ventilation; M, minimum; MP, Mycoplasma pneumoniae; NA, not available; postop day, postoperation day; RT-PCR, reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Respiratory pathogens in our study include respiratory syncytial virus, adenovirus, influenza A, influenza B, parainfluenza virus, Legionella pneumophila, Chlamydophila pneumoniae, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae.

On the first day after the surgery, the number of neutrophils in the peripheral blood was found to be increased in all seven patients, and four patients had lymphopenia. At the onset of COVID-19 infection, five patients had lymphopenia, and a decline in the lymphocyte count was observed in all seven cases, which was more prominent in patients 1, 3, and 7. Regarding liver function, only one patient had increased concentrations of alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase, and three patients had lower albumin level than the reference range (35–52 g/liter). Elevated high-sensitivity C-reactive protein and procalcitonin, the biomarkers for inflammation, were observed in all seven patients at the onset of the symptoms. The levels of fibrinogen and D-dimers were increased in five and seven patients, respectively (Table 2).

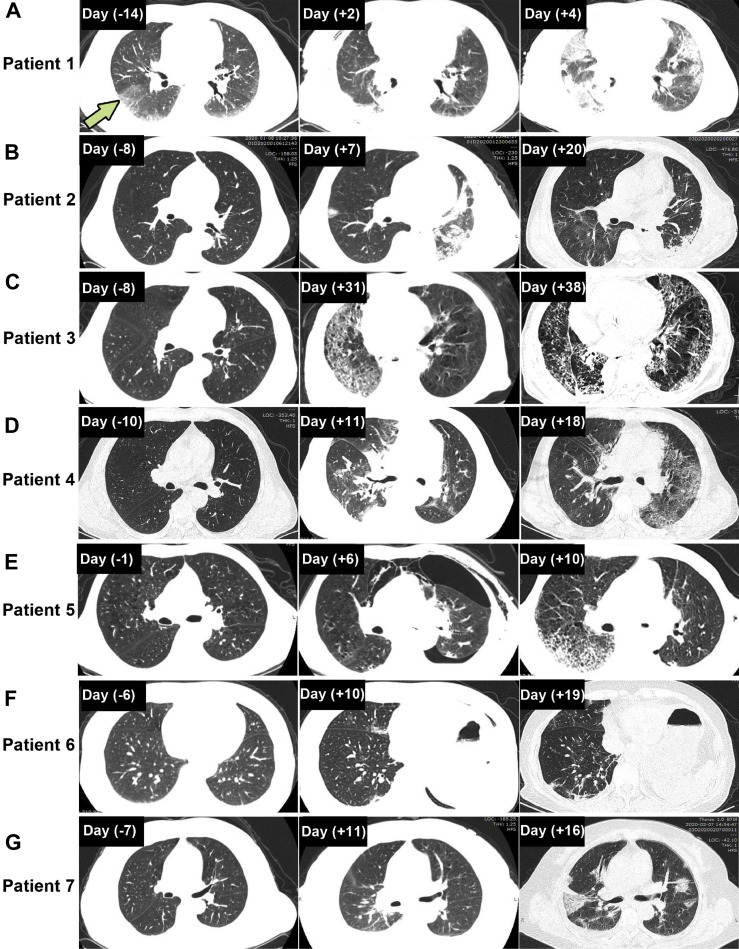

All the patients had computed tomography (CT) scans. After the onset of the symptoms, all seven patients presented with emerging multifocal ground-glass opacities (GGOs) with (four cases) or without (three cases) superimposed reticulation (Fig. 1 A–G). Bilateral involvement and progression on CT images were observed in three patients (patients 1, 3, and 7) (Fig. 1 A, C, and G).

Figure 1.

Representative chest CT images in seven patients with COVID-19. (A) A 63-year-old man who underwent VATS right lower lobe lobectomy and lymphadenectomy. CT scans performed 14 days before the surgery revealed bilateral infiltrative opacification in the periphery of the lung and a subpleural ground-glass attenuation in the right lower lobe (arrow). CT images on postoperative day 4 revealed bilateral multifocal GGOs with consolidation. (B) A 57-year-old man who underwent left lower lobe and segment 4 plus 5 sleeve resection through open surgery. CT scans revealed ground-glass shadowing in the right lung and gradual absorption of infiltration in the left upper lobe from postoperative day 7 to day 20. (C) A 68-year-old man who underwent right lower lobe lobectomy with reconstruction of the right bronchus intermedius and lymphadenectomy. CT images on postoperative days 31 and 38 revealed a mixture appearance of GGOs with superimposed reticulation at bilateral lungs. (D) A 57-year-old man who underwent VATS right upper lobe lobectomy and lymphadenectomy. CT images revealed subsegmental consolidation in the right middle lobe and right encapsulated pleural effusion on postoperative day 11, which gradually resolved on postoperative day 18, and a progression of the ground-glass shadowing in the left lung was presented. (E) A 61-year-old man who underwent VATS left upper lobectomy and lymphadenectomy. CT images revealed pneumothorax and atelectasis on postoperative day 6 that resolved on day 10. CT images on postoperative day 10 revealed presence of GGOs with superimposed reticulation in the periphery of the right lung. (F) A 60-year-old woman who underwent VATS wedge resection of left upper lobe with basal segmentectomy and lymphadenectomy. CT images revealed persistent GGOs in the right middle and lower lobe on postoperative days 10 and 19. (G) A 56-year-old woman who underwent VATS right lower lobe lobectomy. CT images revealed bilateral multifocal GGOs and pleural effusion on postoperative day 16. COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; CT, computed tomography; GGO, ground-glass opacity; VATS, video-assisted thoracic surgery.

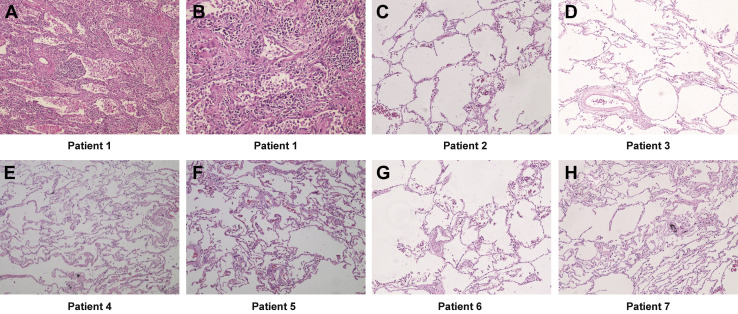

Pathologic examination of the specimens from all these patients was performed. The findings of patient 1 have been reported in a previous study.4 Among all the seven patients, typical malignant pathologic features of the primary tumors were identified. Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections of the lung tissues distant from the tumors were reviewed. For patient 1, there was a wide range of lung interstitial inflammation with numerous infiltrating immune cells seen under the microscope. The infiltrating cells were mainly composed of plasma cells and macrophages, but lymphocytes were rare. Thickened alveolar septum and fibrous connective tissue proliferation were noted. Besides that, there were a large number of macrophages and foam cells in the alveolar cavities, but no evident pneumocyte hyperplasia was observed. Moreover, no obvious viral inclusion bodies and hyaline membrane were found (Fig. 2 A and B). The other six patients had no evident inflammation in their lung tissues distant from the tumors (Fig. 2 C – H).

Figure 2.

Histopathologic examination of lung tissue distant from the tumor. (A) Diffuse lung interstitial inflammation with inflammatory cell infiltration (patient 1, original magnification ×40). (B) Thickened alveolar septum and fibrous connective tissue proliferation accompanied with plasma cell and macrophage infiltrates. Macrophages and foam cells infiltrate the alveolar cavities (patient 1, original magnification ×200). (C–H) Pulmonary histology without inflammation findings (original magnification ×100).

Oseltamivir was initially administered when the seven patients presented with the virus infection-associated symptoms. As the symptoms were progressing, other antivirus regimens were also used, including umifenovir in two patients and lopinavir and ritonavir in one patient. Four patients received systemic corticosteroid therapy. Patients 1, 3, and 7 received mechanical ventilation and eventually died of respiratory failure on postoperative days 5, 42, and 35 (5, 19, and 25 d after the symptom onset), respectively. Two patients have been cured and discharged from the hospital, and the remaining two patients were still hospitalized in stable condition at the time of manuscript submission with normal body temperature for more than 3 days and objective relief from symptoms (Table 2).

Discussion

The incubation period of COVID-19 has been reported to be 5.2 days (95% confidence interval: 4.1–7.0), and for some cases, it could be as long as 14 days.5 To properly identify and screen patients with atypical symptoms during the incubation period is a big challenge. Although the laboratory confirmation of COVID-19 infection was obtained on postoperative day 5, the clinical course of patient 1 revealed that the patient had been infected with SARS-CoV-2 before the surgery. By retrospectively examining his clinical manifestations, we found that the patient immediately developed a fever (38.5°C) just 3 hours after the surgery and had recurrent pyrexia (>39°C) in the whole postoperative period. Chest CT scan on postoperative day 4 revealed diffused GGOs in bilateral lungs. As the pneumonia rapidly worsened, the patient died on day 5 after the surgery. We also reviewed the CT scan image of the patient performed 2 weeks before the surgery and noticed a subpleural ground-glass attenuation in the right lower lobe in addition to the diffusely infiltrative opacifications in the subpleural regions of both lungs, which were previously associated with interstitial lung disease. At that time, there was lack of awareness of the significance of the ground-glass findings.

In the report of Tian et al.,3 pathologic examination of the two cases infected with the novel coronavirus before the lobectomies revealed evident alveolar damage with alveolar edema and proteinaceous exudates. These lung injury findings were also generally observed in patients infected with SARS by autopsy.6 In patient 1, we did not observe typical alveolar damages and pneumocyte hyperplasia; instead, we found extensive interstitial inflammation with numerous plasma cells and macrophages infiltrating the lung tissues. The pathologic pattern of COVID-19 pneumonia in patient 1 differs from that of the two cases reported by Tian et al.3 Given that patient 1 had interstitial lung disease, the pathologic changes may be affected by this pulmonary comorbidity. Taken together, the lesson from patient 1 indicates that it is vitally important to perform careful preoperative examination and screening for those patients who plan to undergo an operation during the COVID-19 epidemic.

All seven patients were found to have postresection changes on radiographic images in the early period after the surgery, including infiltration, atelectasis, and pleural effusion. After the onset of the symptoms, all seven patients presented with emerging multifocal GGOs, which were reported as the most common CT findings of COVID-197 and SARS, as well.8 Although the postresection radiographic abnormalities increased the difficulty in early detection of the viral infection, the typical radiologic features and distribution pattern can facilitate the differential diagnosis because postresection infiltration and effusion mostly developed in the lung on the surgery side. Thus, the presence of typical GGOs, especially in the lobe contralateral to the surgery side, could be an early radiologic sign of the viral infection.

Serial CT scans revealed bilateral lung involvement with evident progression in patients 1, 3, and 7. Despite comprehensive treatment, including antivirals, antibiotics, oxygenation therapy, and other supportive care, these three patients eventually developed respiratory failure and died. In contrast, the other four patients with infection predominantly involving the lung contralateral to the surgery side had less severe symptoms and better prognosis (two were cured and two were in the convalescent stage). This is consistent with the current results among the general infected population,9 which revealed that the bilateral involvement is correlated with high severity and poor prognosis.

Lymphopenia is a common feature for SARS and SARS-CoV-2 infection.10 , 11 It is worth noting that lymphopenia often occurs immediately after lung surgery.12 The results indicated that early appearing lymphopenia after lung resection was because of lack of specificity. At the onset of the symptoms, five cases presented with lymphopenia, and a prominent decline in the lymphocyte count was observed in patients 1, 3, and 7, suggesting the degree of reduction in the number of circulating lymphocytes was closely correlated with the progression of COVID-19. Thus, compared with the absolute cell count, the dynamic reduction of lymphocytes should be considered to be of more significance in the postoperative patients with COVID-19.

Patients with cancer are more susceptible to infection than individuals without cancer because of the immunosuppressive state caused by the malignancy.13 , 14 A recent nationwide analysis of patients with COVID-19, which included a cohort of 18 patients with various cancers and 1572 patients without cancer history, revealed that patients with cancer are at a high risk of severe COVID-19.15 Among the 18 patients with cancer enrolled in this study, five patients had lung cancer. These five patients with lung cancer had lower probability of severe COVID-19 than those with other types of cancer (20% versus 62%, respectively). Nevertheless, the lower incidence of severe COVID-19 in patients with lung cancer should be interpreted with caution because of the small sampling. In our report, six patients had lung cancer, and two of them died. Some considerations also need to be taken into account in interpreting the findings from the current report. First, the effects of different surgery patterns, including operation approach and lymphadenectomy on COVID-19, remain to be evaluated. Second, whether the characteristics of the cancer, such as histologic type and stage, could influence the development and prognosis of COVID-19 in patients with lung cancer needs to be further investigated. For now, two patients are still hospitalized, and further follow-up is needed to clarify the long-term outcomes of such specific patients infected with SARS-CoV-2.

Before the outbreak was declared by the national authority, our understanding of the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 was very limited. The lack of awareness of this emerging infectious disease led to the failure of implementing appropriate protective measures in place to prevent health care–associated infection. A comprehensive analysis of nosocomial infection of Middle East respiratory syndrome in a tertiary hospital in South Korea revealed that the virus transmissions mainly occurred before the infected patient had been recognized.16 In our department, nosocomial transmission could be definitively proven on the basis of timing and pattern of exposure to infected patients and subsequent development of infection among the medical staff. On the basis of the investigation, patient 1 was presumed to be the source of transmission in our department because he was the first confirmed case in the ward and three health care workers who had close contact with him were found to be infected. Subsequently, six patients and another five health care workers were confirmed infected with COVID-19. The cross-infection highlighted the high risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission within a thoracic surgery department. As there are more aerosol-generating procedures performed, such as lung suctioning, intubation, and bronchoscopy, in the thoracic surgery department, the medical staff has a high risk of exposure to droplets around the patients.

The outbreak of COVID-19 imposes a major challenge in deciding and managing surgical operation on patients with lung cancer and other lung disorders. We believe that it is imperative to report these cases to provide direct evidence for choosing proper strategies in the thoracic department. The preliminary results from the limited cases indicate that lung resection surgery might be a risk factor for death in patients with COVID-19 in the perioperative period. Thus, during the epidemic, any surgery-related managements should be manipulated with extra caution. At the epidemic area, any negligence is unaffordable.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the patients and their families involved in the study. This study was approved by the ethics committee of Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, People’s Republic of China.

Footnotes

Drs. Cai, Hao, and Gao contributed equally to this work.

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.World Health Organization Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report-45. 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200305-sitrep-45-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=ed2ba78b_4 Accessed March 5, 2020.

- 2.Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China [e-pub ahead of print]. N Engl J Med. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2002032, accessed March 3, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Tian S, Hu W, Niu L, H Liu, H Xu, SY Xiao. Pulmonary pathology of early-phase 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pneumonia in two patients with lung cancer [e-pub ahead of print]. J Thorac Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2020.02.010, accessed March 1, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Kuang D., Xu S.P., Hu Y., Liu C., Duan Y.Q., Wang G.P. The pathological changes and related studies of novel coronavirus infected surgical specimen. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2020;49:E008. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112151-20200315-00205. [in Chinese] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li Q., Guan X., Wu P. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1199–1207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hwang D.M., Chamberlain D.W., Poutanen S.M., Low D.E., Asa S.L., Butany J. Pulmonary pathology of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Toronto. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:1–10. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung M., Bernheim A., Mei X. CT imaging features of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Radiology. 2020;295:202–207. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ooi G.C., Daqing M. SARS: radiological features. Respirology. 2003;8(suppl):S15–S19. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1843.2003.00519.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shi H., Han X., Jiang N. Radiological findings from 81 patients with COVID-19 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:425–434. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30086-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li T., Qiu Z., Zhang L. Significant changes of peripheral T lymphocyte subsets in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:648–651. doi: 10.1086/381535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China [e-pub ahead of print]. JAMA. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama2020.1585, accessed February 20, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Dupont G., Flory L., Morel J. Postoperative lymphopenia: an independent risk factor for postoperative pneumonia after lung cancer surgery, results of a case-control study. PLoS One. 2018;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0205237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holland T., Fowler V.G., Jr., Shelburne S.A., 3rd Invasive gram-positive bacterial infection in cancer patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(suppl 5):S331–S334. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vijayan D., Young A., Teng M.W.L., Smyth M.J. Targeting immunosuppressive adenosine in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17:709–724. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2017.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liang W., Guan W., Chen R. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. The Lancet Oncology. 2020;21:335–337. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30096-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ki H.K., Han S.K., Son J.S., Park S.O. Risk of transmission via medical employees and importance of routine infection-prevention policy in a nosocomial outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS): a descriptive analysis from a tertiary care hospital in South Korea. BMC Pulm Med. 2019;19:190. doi: 10.1186/s12890-019-0940-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]