Abstract

Background

Ever more patients are being treated with invasive ventilation in the outpatient setting. Most have no access to a structured weaning process in a specialized weaning center. The personal burden on the patients is heavy, and the costs for the health care system are high.

Methods

61 patients who had been considered unfit for weaning were admitted to a weaning center. The primary endpoint was the number of patients who had been successfully weaned from the ventilator at six months. The comparison group consisted of health-insurance datasets derived from patients who were discharged from an acute hospital stay to receive invasive ventilation in the outpatient setting.

Results

50 patients (82%; 95% confidence interval [70.5; 89.6]) were successfully weaned off of invasive ventilation in the weaning centers, 21 of them (34% [23.8; 47]) with the aid of non-invasive ventilation. The survival rate at 1 year was higher than in the group without invasive ventilation (45/50, or 90%, versus 6/11,or 55%); non-invasive ventilation was comparable in this respect to no ventilation at all. The identified risk factors for weaning failure included the presence of more than five comorbidities and a longer duration of invasive ventilation before transfer to a weaning center.

Conclusion

If patients with prolonged weaning are cared for in a certified weaning center before being discharged to receive invasive ventilation in the outpatient setting, the number of persons being invasively ventilated outside the hospital will be reduced and the affected persons will enjoy a higher survival rate. This would also spare nursing costs.

Weaning is the process of discontinuing invasive ventilation. The reasons behind the ever increasing need for invasive ventilation include demographic trends resulting in a growing number of older patients, often with chronic lung diseases and multiple comorbidities, as well as progress in medical technology and improved prognosis especially among older and multimorbid patients receiving acute treatment in the intensive care setting (1).

Weaning is classified into three categories: simple, difficult, and prolonged (2). Patients in the “prolonged” group have a significantly reduced life expectancy compared to the “simple” and “difficult” groups, with data on the mortality rate in prolonged weaning varying between 14% and 32% (3, 4).

Prolonged weaning (category 3) is defined as cases in which patients are definitively weaned from mechanical ventilation only after three unsuccessful spontaneous breathing trials (SBT) or after more than 7 days of invasive ventilation after the first unsuccessful SBT (5). In recent years, the number of intensive care patients that could not be weaned from the ventilator—or could only be weaned in an extremely prolonged manner—has risen.

Parallel to the increase in patients requiring prolonged weaning, the number of patients with weaning failure and a life following long-term ventilation is also rising (6– 8). However, according to the evidence to date, 85% of patients discharged with invasive ventilation to domiciliary intensive care had not received prior treatment in a certified weaning center (9, 10). Although the number of beds available to this end in certified weaning centers in Germany is not precisely documented, estimates from the German Institute for Lung Research (Institut für Lungenforschung) and the spokesperson for WeanNet put it at around 350–450.

There are currently estimated to be around 20 000 patients receiving invasive ventilation as part of home-based intensive care in Germany, whereby this number has been rising for years (11, 12). Patients in whom weaning fails are either discharged home to be cared for around the clock by outpatient intensive care teams or receive care in special respiratory care homes or residential communities, the latter corresponding in form to an own domestic setting.

The outpatient care of patients with invasive domiciliary ventilation is cost-intensive, whereby the costs vary according to the type of facility. The average cost of care per year and patient is approximately 240 000 Euro (12). The medical quality of this domiciliary care varies considerably, since there are no standards governing personnel or equipment, nor is there any infrastructure for quality assurance. As a rule, patients are cared for in these residential groups by general practitioners that have no special qualifications or experience in respiratory medicine, meaning one can assume that the specialist medical care is inadequate (13, 14).

Based on own experience, the objective was to demonstrate that patients initially considered to be unweanable can indeed be weaned from ventilation in a second step with the help of a certified weaning center.

Methods

A multicenter non-randomized controlled observational study was conducted at Germany‘s university or university-associated weaning centers, led by pulmonologists at the University of Greifswald, Cologne-Merheim Lung Center, and the Thorax Clinic in Heidelberg. At the time of participation, the three study centers were certified weaning centers according to WeanNet, a network of weaning centers under the specialist medical direction of the German Respiratory Society (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Pneumologie und Beatmungsmedizin).

The study included patients that were either to be discharged from an emergency care department to domiciliary ventilation and for whom transitional management had already been initiated as a marker that weaning had been classified as terminated and unsuccessful (N = 49), or patients that had undergone secondary transfer from domiciliary ventilation to a certified weaning center (N = 16). Only patients for whom a prolonged weaning process could actually be assumed were included in the study. Patients with unstable health status, as well as those requiring emergency treatment interventions, were not included in the study. This means that patients only participated if they were stable to a level that they could have been discharged to domiciliary ventilation.

In the weaning centers, a renewed weaning phase in accordance with the guidelines (15) was initiated and performed under inpatient conditions, regular medical monitoring, and intensive physiotherapeutic treatment and mobilization. Patients not requiring renewed invasive ventilation over a time period of 72 h were classified as weaned—irrespective of whether non-invasive ventilation was continued. Those patients that continued to require ventilation via a tracheal cannula were classified as unweaned.

Patients were assigned to the intervention group in a prospective manner according to the defined inclusion criteria at the individual centers. Following discharge from the weaning phase, the patient‘s status was recorded at 3, 6, and 12 months. Exclusion criteria included diseases with an estimated survival prognosis of under 6 months (for example, metastatic cancer) and severe, irreversible neurological disorders (for example, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis). The primary endpoint of the investigation was the percentage of patients that were successfully weaned after 6 months and required no further invasive ventilation (expected percentage, 60%).

Secondary endpoints included 1-year survival, predictive analyses, and a comparison of health costs. In order to make a cost calculation, statutory health insurance datasets were used, consisting of patients that were discharged unweaned—and requiring invasive ventilation—to the domiciliary ventilation setting.

Descriptive and analytical statistics were performed with SPSS Version 25 (IBM Germany). Spearman‘s Rank correlation coefficient was used for the correlation analysis. The groups were compared using the log-rank test, while comorbidities and duration of ventilation in the three groups (fully weaned, partially weaned with mask, not weaned) were compared using the Kruskal Wallis test. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to plot the survival curve. P-values serve to estimate the probability that results were obtained randomly and are used in an exploratory manner in this study.

Results

A total of 65 patients were included according to the above-mentioned criteria. Two patients withdrew their consent after initially agreeing to participate and two patients withdrew from follow-up, meaning that data on 61 patients were evaluated; 45 of these were recruited from the Heidelberg center, 11 from Cologne, and five from Greifswald. Table 1 shows the demographic data of patients.

Table 1. Basic patient data.

| N | % | MV | SD | Range | |

| Female | 17 | 28 | |||

| Age | 61 | 100 | 67.1 | 10.3 | 28–87 |

| BMI | 61 | 100 | 26.9 | 11.2 | 14–40 |

| Long-term O2 therapy prior to intubation | 11 | 18 | |||

| Duration of external ventilation (days) | 61 | 100 | 30.1 | 23.6 | 7–107 |

| Tracheal cannula, yes | 61 | 100 | |||

| Never-smokers | 13 | 21.3 | |||

| Ex-smokers (>3 months) | 16 | 26.2 | |||

| Current smokers | 32 | 52.4 |

MV, mean value; SD, standard deviation

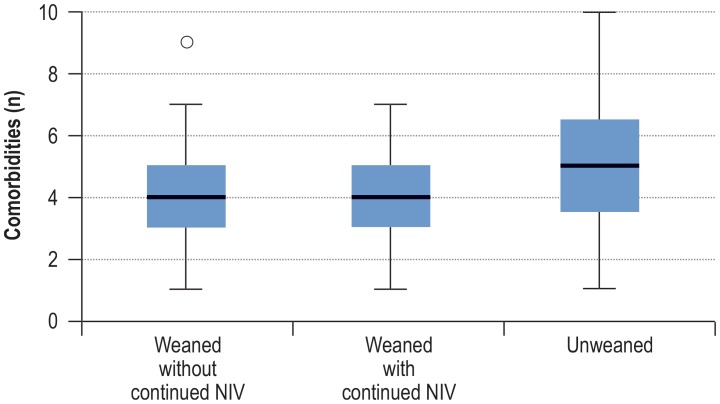

In most cases, acutely exacerbated chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or pneumonia had led to ventilation dependence (table 2). The patients had a varying number of comorbidities. On average, patients exhibited five comorbidities (median, range 1–10), the number of which was descriptively slightly lower at 4 (compared to 5.3) in patients that could be weaned (p = 0.43) (Table 3, Figure 1).

Table 2. Causes leading to ventilation.

| Frequency | Percent | |

| Acutely exacerbated COPD | 26 | 42.6 |

| Postoperative respiratory insufficiency | 1 | 1.6 |

| Decompensated heart failure | 2 | 3.3 |

| Trauma | 1 | 1.6 |

| Pneumonia | 18 | 29.5 |

| Obesity hypoventilation syndrome | 4 | 6.6 |

| ARDS | 3 | 4.9 |

| Sepsis | 3 | 4.9 |

| Other | 3 | 4.9 |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease;

ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome

Table 3. Number and distribution of recorded comorbidities.

| Frequency | Percent | |

| COPD | 26 | 42.6 |

| Critical illness polyneuropathy | 7 | 11.4 |

| Coronary heart disease | 24 | 39.3 |

| Immunosuppression | 0 | 0 |

| Delirium | 15 | 24.6 |

| Interstitial lung disease | 2 | 3.3 |

| Restrictive lung disease | 2 | 3.3 |

| Kidney failure | 23 | 37.7 |

| Oncological disease | 7 | 11.5 |

| Pneumonia | 36 | 59.0 |

| Left heart failure | 14 | 23.0 |

| Arterial hypertension | 38 | 62.3 |

| Obesity | 22 | 36.1 |

| Diabetes | 19 | 31.1 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 4 | 6.6 |

| Other | 15 | 24.6 |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Figure 1.

The average number of comorbidities was somewhat lower among successfully weaned patients compared to patients that could not be weaned (4 versus 5.3).

NIV, non-invasive ventilation; o marks a statistical outlier

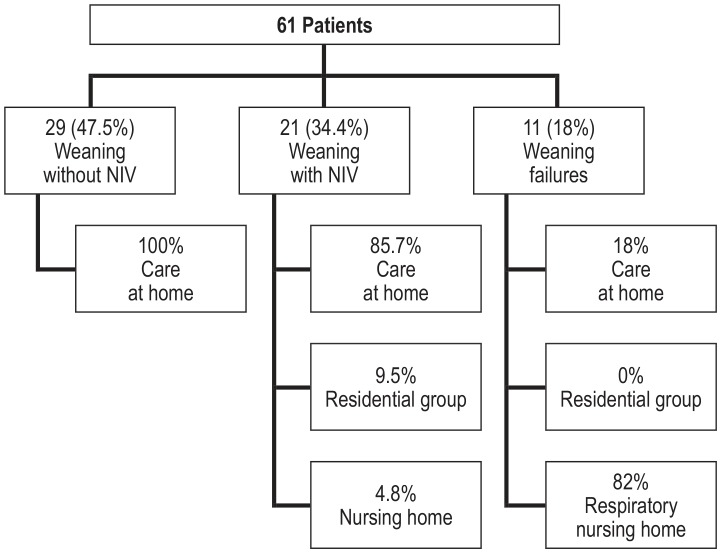

At the weaning centers, it was possible to wean 29 patients (48%; 95% confidence interval: [35.5; 59.8]) without the need to continue non-invasive ventilation (NIV), 21 (34% [23.8; 47]) could be weaned using non-invasive mask ventilation, and 11 patients (18% [10.4; 29.5]) were unweanable and continued to require invasive ventilation. If one pools the weaned patients with and without NIV, weaning was successful in 50 of the study patients (82 % [70,5; 89,6]). When taking into account the patients that dropped out of follow-up, the percentage is still at almost 79%.

The average inpatient stay in weaning centers was 24.7 days (range 5–124 days, SD ± 22 days, median 21 days). All patients left the weaning centers alive; however, one patient died of advanced cancer after 28 days while still in hospital, putting the 30-day mortality rate at 1.6%.

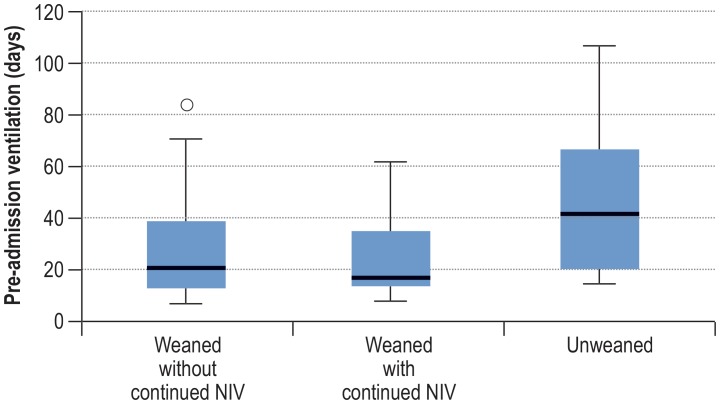

It was found that, for patients with weaning failure, the average length of external ventilation prior to admission to a weaning center was higher at 48.1 days (range 15–107 days, SD ± 33.3 days, median 42 days) compared to 26.2 days for successfully weaned patients (range 7–84 days, SD ± 17.5 days, median 20 days; Kruskall-Wallis test: p = 0.043; Figure 2). Figure 3 shows the centers at which patients in the intervention group continued to receive care following weaning.

Figure 2.

Patients with weaning failure were ventilated on average for longer prior to admission to the weaning center compared to successfully weaned patients (48.1 versus 26.2 days).

NIV, non-invasive ventilation; o marks a statistical outlier

Figure 3.

Continued care of patients depending on weaning success

NIV, non-invasive ventilation

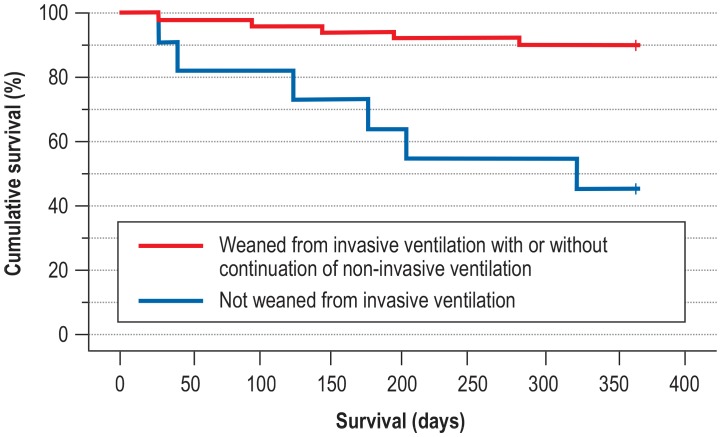

Over the course of the year, 11 patients (18%) died, six of which were in the group requiring continued invasive ventilation and five in the secondary-weaning group. If one analyzes 1-year survival in relation to weaning success, one sees that the patients in whom weaning was successful survived longer compared to those in whom invasive ventilation was continued (p: 0.000197; hazard ratio: 0.14 [0.04; 0.47]). There was no difference between those that were weaned with and those that were weaned without continued NIV (figure 4).

Figure 4.

1-Year survival in relation to weaning success

Weaned: p = 0.000197; hazard ratio (HR): 0.14; 95% confidence interval: [0.04; 0.47] not weaned: p = 0.000197; HR: 7.0 [2.13; 23.05])

In order to compare the costs of ongoing care, the AOK, a German statutory health insurer, provided the data for 61 ventilation-dependent patients comparable in terms of age and sex that had been discharged—without participating in a structured weaning process—to domiciliary respiratory care in a certified weaning center. These data revealed annual care costs totaling 14 301 000 Euro.

The costs of placing patients that were weaned and discharged home was put at 0 Euro. These patients required no further respiratory care support.

If one adds up the costs, as billed according to the DRG system, for weaning the 61 patients, these total 4 126 782 Euro or an average cost of 67 652 Euro/patient (range, 7015–169 520 Euro). This figure includes all services provided on an inpatient basis. The cost of domiciliary care for patients discharged from the weaning center in whom weaning failed in this secondary setting totaled 2 880 720 Euro/year. If one compares the total costs of around 7 million Euro with the costs for the comparison group, one sees that it was possible to reduce costs in the intervention group by approximately 7 million Euro in the first year. However, these are merely approximate figures, since only the costs of weaning and respiratory care were compared here.

Discussion

In total, 50 of the 61 patients (82%) deemed unweanable and included in the study were successfully weaned from invasive ventilation at the participating weaning centers. In line with the international consensus (5, 13), the transition to NIV is deemed weaning success, since it provides an adequate level of autonomy and quality of life, despite not achieving full independence from the ventilator. Weaning from invasive ventilation succeeded in 29 patients (48%), while continuation with NIV was required in 21 (31%). This tallies with published, mostly retrospective analyses on the course of primary weaning (16– 21). A comparison reveals that the success rate of this intervention is in the upper range (7, 22). As in older studies, the most frequent causes of primary weaning failure included acutely exacerbated COPD or pneumonia (1, 18, 19, 23).

The analysis of possible predictive factors for weaning success revealed, as in retrospective data, that the duration of ventilation prior to transfer to a specialized center represented a factor for weaning success (18, 19, 21, 23). For example, patients that were successfully weaned were mechanically ventilated for 20 days on average prior to transfer, patients that were unweanable for 40 days on average.

Weaning success is clearly associated with the number of comorbidities; with regard to individual comorbidities, only overweight patients showed a trend towards better weanability from invasive ventilation. This can likely be explained by their catabolic metabolic status during the period of mechanical ventilation (24).

A structured weaning process frequently made it possible for patients in prolonged weaning to be successfully weaned in a second step. Therefore, in future, patients at risk for prolonged weaning should undergo a structured and certified weaning process in a timely manner. If this reduces the overall weaning process, more weaning capacity is freed up (18, 19). These structures are available in Germany and should be used. Conclusions based on a significantly larger data pool should be possible once the WeanNet database has been evaluated (25). There are no data on how often patients receiving invasive ventilation at home are re-evaluated in centers.

Analysis of the 1-year follow-up revealed that patients that could be weaned from invasive ventilation have a better 1-year survival rate compared to patients requiring invasive ventilation in the domiciliary setting. With regard to causes of death, it was found that patients with oncological diseases had worse survival compared to those without oncological diseases. Patients with diabetes tended to have better survival compared to patients without diabetes.

The observation that diabetics exhibit better long-term survival has not been previously described as such and cannot be explained with the available data. In relation to other comorbidities or other aspects of care, such as long-term oxygen therapy, no statistically significant data were recorded either for outcome or for 1-year survival. Mention must be made here of the limited number of patients. The fact that 61 patients were included resulted in part in extremely small subgroups, meaning that the statistical conclusions could only reach significance with larger patient groups.

In the intervention group, it was possible to discharge all patients weaned from invasive ventilation without continued NIV into home care with no ongoing respiratory care. Of the NIV patients, 85% returned to the home setting, 10% were discharged to residential care groups, and 5% to nursing homes.

Since a number of patients in the intervention group died and, therefore, out-of-hospital care was not required for 12 months, the costs for deceased patients were projected over 1 year in the hypothetical approach. Even if one looks at the total costs of weaning and hypothetical care in the case of 100% 1-year survival, totaling 7 million Euro, one stills sees a saving of 50% of the costs generated without a secondary attempt at weaning.

This study has demonstrated that 82% of patients classified as unweanable can be weaned from invasive ventilation in the context of a structured weaning process at a certified center, and that this outcome results in better survival and a significant reduction in costs.

The study has a number of limitations. Firstly, due to the focus of the weaning centers, primarily patients with internal medical diseases were admitted for weaning, while neuromuscular disorders were not recorded. In addition, only three of the planned seven centers were ultimately able to include patients, and this with an uneven distribution, since patient recruitment proved difficult due to a lack of personnel; however, recruitment in Heidelberg was more expeditious thanks to close ties to out-of-hospital respiratory facilities. A further limitation is the sample size. The analysis in particular of outcome and survival parameters revealed that some factors occurred so rarely that it is not possible to generate sufficiently reliable statistics. Mention may be made here of the pending evaluation of the WeanNet database, to which this prospective study should be seen as complementary, especially to the cost calculation. Moreover, the PRiVENT study supported by the GBA (01NVF19023), the aim of which will be the prevention of invasive long-term ventilation through the early use of weaning centers, also needs to be awaited.

Key messages.

The increasing number of patients requiring invasive ventilation in the domiciliary care setting is evolving into a problem in the provision of care.

Patients should receive treatment at a weaning center prior to being discharged with invasive ventilation.

In weaning centers, weaning from invasive ventilation was successful in 82% of patients previously considered to be unweanable.

With regard to long-term survival, non-invasive ventilation was equivalent to weaning from invasive ventilation without ongoing NIV.

The use of weaning centers saves enormous costs in outpatient nursing care.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Christine Rye.

Footnotes

Funding

This study was financially supported by the German Federal Ministry of Health (Bundesministerium für Gesundheit, BMG). The financial support relates to the scientific elaboration of the data, but not the treatment of patients in the clinical setting.

The study was approved by the Ethics Commission of the University of Witten/Herdecke (application number 48/2015).

Conflict of interests

Dr. Magnet received consulting fees from Sentec. Her travel expenses and participation fees were reimbursed by Löwenstein Medical. She received lecture fees from GHD Gesundheits GmbH, Smiths Medical, and Sentec.

The scientific working group led by Prof. Windisch received research grants from Weinmann/Germany, Vivisol/Germany, Heinen und Löwenstein/Germany, VitalAire/Germany, and Philips Respironics/USA. Prof. Windisch received lecture fees from Löwenstein and ResMed.

The remaining authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Schönhofer B, Berndt C, Achtzehn U, et al. Entwöhnung von der Beatmungstherapie Eine Erhebung zur Situation pneumologischer Beatmungszentren in Deutschland. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2008;133:700–704. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1067309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacIntyre N, Epstein S, Carson S, et al. Management of patients requiring prolonged mechanical ventilation: report of NAMDRC consensus conference. Chest. 2005;128:3937–3954. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.6.3937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Funk GC, Anders S, Breyer MK, et al. Incidence and outcome of weaning from mechanical ventilation according to new categories. Eur Respir J. 2010;35:88–94. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00056909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WeanNet. The network of weaning units of the DGP (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Pneumologie und Beatmungsmedizin) - results to epidemiology and outcome in patients with prolonged weaning. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2016;141:e166–e172. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-112345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boles JM, Bion J, Connors A, et al. Weaning from mechanical ventilation. Eur Respir J. 2007;29:1033–1056. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00010206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peñuelas O, Frutos-Vivar F, Fernández C, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of ventilated patients according to time to liberation from mechanical ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:430–437. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201011-1887OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sellares J, Ferrer M, Cano E, Loureiro H, Valencia M, Torres A. Predictors of prolonged weaning and survival during ventilator weaning in a respiratory ICU. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37:775–784. doi: 10.1007/s00134-011-2179-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cox CE, Carson SS. Medical and economic implications of prolonged mechanical ventilation and expedited post-acute care. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;33:357–361. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1321985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.et al. Deutsche Interdisziplinäre Gesellschaft für Außerklinische Beatmung. Positionspapier zur aufwendigen ambulanten Versorgung tracheotomierter Patienten mit und ohne Beatmung nach Langzeit-Intensivtherapie (sogenannte ambulante Intensivpflege) Pneumologie. 2017;71:204–206. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-104028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Institut für Qualitätssicherung und Transparenz im Gesundheitswesen (IQTIG) Qualitätsverträge nach § 110a SGB V. Evaluationskonzept zur Untersuchung der Entwicklung der Versorgungsqualität gemäß § 136b Abs. 8 SGB V. Abschlussbericht, erstellt im Auftrag des Gemeinsamen Bundesausschusses. www.g-ba.de/downloads/39-261-3376/2018-06-21_Freigabe_IQTIG-Bericht_Evaluationskonzept_ Q-Vertraege_inkl-Anlagen.pdf (last accessed on 21 January 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karagiannidis C, Strassmann S, Callegari J, Kochanek M, Janssens U, Windisch W. Epidemiologische Entwicklung der außerklinischen Beatmung: Eine rasant zunehmende Herausforderung für die ambulante und stationäre Patientenversorgung. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2019;144:e58–e63. doi: 10.1055/a-0758-4512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lehmann Y, Ostermann J, Reinhold T, Ewers M. Descriptive analysis of health economics of intensive home care of ventilated patients. Gesundheitswesen. 2019;81:813–821. doi: 10.1055/a-0592-6861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Windisch W, Dreher M, Geiseler J, et al. Guidelines for non-invasive and invasive home mechanical ventilation for treatment of chronic respiratory failure - Update 2017. Pneumologie. 2017;71:722–795. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-118040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stieglitz S, Randerath W. Weaning failure: follow-up care by the weaning centres—home visits to patients with invasive ventilation. Pneumologie. 2012;66:39–43. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1291439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schönhofer B, Geiseler J, Dellweg D, et al. S2k-Leitlinie „Prolongiertes Weaning“. Pneumologie. 2015;69:595–607. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1392809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pilcher DV, Bailey MJ, Treacher DF, Hamid S, Williams AJ, Davidson AC. Outcomes, cost and long term survival of patients referred to a regional weaning centre. Thorax. 2005;60:187–192. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.026500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Béduneau G, Pham T, Schortgen F, et al. Epidemiology of weaning outcome according to a new definition The WIND Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:772–783. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201602-0320OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Magnet FS, Bleichroth H, Huttmann SE, et al. Clinical evidence for respiratory insufficiency type II predicts weaning failure in long-term ventilated, tracheotomised patients: a retrospective analysis. J Intensive Care. 2018;6 doi: 10.1186/s40560-018-0338-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muzaffar SN, Gurjar M, Baronia AK, et al. Predictors and pattern of weaning and long-term outcome of patients with prolonged mechanical ventilation at an acute intensive care unit in North India. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2017;29:23–33. doi: 10.5935/0103-507X.20170005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Damuth E, Mitchell JA, Bartock JL, Roberts BW, Trzeciak S. Longterm survival of critically ill patients treated with prolonged mechanical ventilation: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3:544–553. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00150-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lai CC, Shieh JM, Chiang SR, et al. The outcomes and prognostic factors of patients requiring prolonged mechanical ventilation. Sci Rep. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep28034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hannan LM, Tan S, Hopkinson K, et al. Inpatient and long-term outcomes of individuals admitted for weaning from mechanical ventilation at a specialized ventilation weaning unit. Respirology. 2013;18:154–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2012.02266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang JR, Yen SY, Chien JY, Liu HC, Wu YL, Chen CH. Predicting weaning and extubation outcomes in long-term mechanically ventilated patients using the modified Burns Wean Assessment Program scores. Respirology. 2014;19:576–582. doi: 10.1111/resp.12266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Polverino E, Nava S, Ferrer M, et al. Patients‘ characterization, hospital course and clinical outcomes in five Italian respiratory intensive care units. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36:137–142. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1658-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schönhofer B. WeanNet: Das Netzwerk pneumologischer Weaningzentren. Pneumologie. 2019;73:74–80. doi: 10.1055/a-0828-9710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]