Abstract

Background

To accommodate the increasing number of patients requiring prolonged weaning from mechanical ventilation, specialized weaning centers have been established for patients in whom weaning on the intensive care unit (ICU) was unsuccessful.

Methods

This study aimed to determine both the outcome of treatment and the factors associated with prolonged weaning in patients who were transferred from the ICU to specialized weaning centers in Germany during the period 2011 to 2015, based on a nationwide registry covering all specialized weaning centers currently going through the process of accreditation by the German Respiratory Society.

Results

Of 11 424 patients, 7346 (64.3%) were successfully weaned, of whom 2236 were switched to long-term non-invasive ventilation; 1658 (14.5%) died in the weaning unit; and 2420 (21.2%) could not be weaned. The duration of weaning decreased significantly from 22 to 18 days between 2011 and 2015 (p <0.0001). Multivariate analysis revealed that the factor most strongly associated with in-hospital mortality was advanced age (odds ratio [OR] 11.07, 95% confidence interval [6.51; 18.82], p <0.0001). The need to continue with invasive ventilation was most strongly associated with the duration mechanical ventilation prior to transfer from the ICU (OR 4.73 [3.25; 6.89]), followed by a low body mass index (OR 0.38 [0.26; 0.58]), pre-existing neuromuscular disorders (OR 2.98 [1.88; 4.73]), and advanced age (OR 2.96 [1.87; 4.69]) (each p <0.0001).

Conclusions

Weaning duration has decreased over time, but prolonged weaning is still unsuccessful in one third of patients. Overall, the results warrant the establishment of specialized weaning centers. Variables associated with death and weaning failure can be integrated into ICU decision-making processes.

Invasive mechanical ventilation via an endotracheal or tracheal tube is a frequently performed procedure in the intensive care unit (ICU). When the acute condition that has required invasive mechanical ventilation is resolved, the ventilation must be discontinued. This process, known as weaning (box), constitutes a significant part of intensive care [1, 2]. A delay in weaning has been demonstrated to be associated with higher complication rates, longer hospital stays, and a lower ICU survival rate [3, 4]. In 2005, following the International Consensus Conference (ICC), the process of weaning was categorized, according to expert opinion, into three groups based on the number, timing, and success of spontaneous breathing trials (SBT): simple, difficult, and prolonged weaning (box). Subsequent studies showed that prolonged weaning is indeed associated with the worst prognosis [5–10]. However, the factors associated with weaning failure are not included in the ICC criteria.

BOX. Weaning and prolonged weaning.

Invasive mechanical ventilation following intubation is a procedure frequently used in intensive care medicine to treat acute respiratory insufficiency or to permit general anesthesia for surgical procedures. Eventually, however, all patients have to be weaned, i.e., detached from endotracheal artificial airways and invasive mechanical ventilation. It is estimated that the weaning process occupies up to 50% of the total time on ventilation, depending on the individual circumstances. Especially elderly patients and those with pre-existing respiratory disorders and/or important comorbidities such as cardiac insufficiency or neurological disorders are prone to prolonged weaning, where the patient fails at least three spontaneous breathing trials or requires more than 7 days of weaning after the first spontaneous breathing trial (International Consensus Conference criteria). Prolonged weaning may be unsuccessful: some patients die in the hospital, while others are discharged to continue invasive ventilation in the community following tracheostomy. Since prolonged weaning massively impacts on morbidity and mortality, so-called weaning centers have been established in Germany. In these institutions, maximum interdisciplinary effort is made to wean patients who could not be weaned in the intensive care unit from which they were transferred. If weaning remains unsuccessful, however, invasive ventilation has to be continued in the community (the patient’s own home, shared accommodation, or a dedicated care home). In this case, the necessary specialized nursing care can incur costs of up to approximately € 25 000 per month (depending on health insurance company and federal state). Unsuccessful weaning thus has considerable economic consequences.

Importantly, the ICC classification [2] does not address patients who have been transferred to specialized weaning centers because weaning on the ICU has failed. These patients may eventually be weaned successfully after several weeks of invasive mechanical ventilation, although some require long-term non-invasive ventilation (NIV) [11]. By contrast, patients with definitive weaning failure are transferred to long-term care facilities or even discharged home to continue long-term invasive mechanical ventilation there [12–14]. Failure of weaning, however, is associated with substantially greater morbidity and mortality and also represents an economic burden on the health care system (box).

To improve the success of weaning, specialized weaning centers have been established in many countries, including Germany [15–19]. In addition, the German Respiratory Society (DGP) has compiled detailed guidelines on the topic of prolonged weaning [16]. The specialized weaning centers are accredited in accordance with defined criteria laid down by the DGP’s WeanNet initiative [20]. This initiative may well be highly important in light of the steadily increasing number of patients with ventilation outside the hospital setting; an exponential increase was recently reported in the number of patients with established home mechanical ventilation who are subsequently readmitted to the hospital, from 24 845 in 2006 to 86 117 in 2016 [21], although detailed information on the development of prolonged weaning is still lacking.

As a condition for accreditation, specialized weaning centers are required to register their patients in a predefined database. This German registry formed the basis of this study, whose goal was to assess the success of treatment in weaning centers. Moreover, the study also aimed to assess changes in weaning outcome over a period of 5 years and to identify factors associated with successful weaning.

Methods

Ethics committee approval

WeanNet registry data from the period between 1 January 2011 and 1 January 2016 were analyzed. Although data collection was carried out prospectively for the purpose of the accreditation of German weaning centers, all analyses were performed exploratively without predefined hypotheses. The study was approved by the ethics committee of Witten/Herdecke University (eMethods).

Additional detailed information on the WeanNet initiative and the accreditation criteria is provided in the (eMethods).

Data processing

Anonymous raw data were exported from the weaning registry and imported into the Statistica (version 10) software tool. Original variables were recoded for analysis where necessary and further time periods and additional control variables were calculated (eMethods). A plausibility analysis was performed according to predefined criteria. Source data verification was initiated in all cases of inconsistency or missing data with regard to weaning classification. Missing values were added and incorrect data were corrected in all cases of successful source data verification by November 2016.

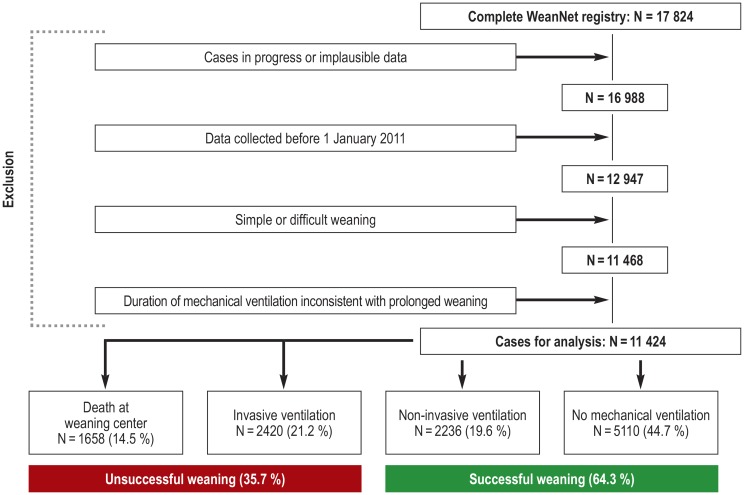

All cases with persistently inconsistent values for treatment phases and weaning classification were subsequently excluded from the final analysis, as were all data sets entered before 1 January 2011. Only patients with prolonged weaning according to the ICC classification were analyzed (Figure 1). In the remaining cases, individual implausible parameters were set to “missing” according to predefined criteria before commencing the analysis. Weaning success was defined as discharge from the weaning unit without the need for continued invasive ventilation.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of registry data analysis and patient outcome

Of 17 824 patients, 713 cases in progress and 123 cases with implausible data were excluded from further analysis.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by data-quest GmbH in close collaboration with the DGP. The results were expressed as median and quartiles. A two-tailed p-value less than 0.05 was considered to be significant if not otherwise stated. All data were analyzed using Statistica (version 10) software. Univariate and multivariate analyses of the variables associated with the risk of mortality, invasive community mechanical ventilation, and long-term non-invasive community mechanical ventilation were performed, respectively. The local ɑ level was adjusted for multiple tests according to the Bonferroni method (eMethods).

Results

Data were analyzed from a total of 11 424 patients with prolonged weaning who were treated in 85 specialized weaning centers (Figure 1, eMethods, eTable 1).

eTable 1. The specialized weaning centers in Germany that are organized within the WeanNet network of the German Respiratory Society and the number of patients recruited at each center.

| Center | Number of patients |

| Solingen, Krankenhaus Bethanien | 505 |

| Schmallenberg, Fachkrankenhaus | 502 |

| Wangen, Fachkliniken | 456 |

| Hamburg, Asklepios Klinik Harburg | 432 |

| Gerlingen, Klinik Schillerhöhe | 370 |

| Hagen, Helios Klinik | 341 |

| Bad Lippspringe, Karl-Hansen-Klinik | 337 |

| Berlin, Evangelische Lungenklinik | 332 |

| Münnerstadt, Thoraxzentrum Bezirk Unterfranken | 331 |

| Hemer, Lungenklinik | 320 |

| Krefeld, Helios Klinikum | 310 |

| Greifswald, Universitätsklinikum | 283 |

| Dortmund, Knappschaftskrankenhaus | 282 |

| Köln, Krankenhaus der Augustinerinnen | 276 |

| Bad Berka, Zentralklinik | 274 |

| Essen, Ruhrlandklinik | 261 |

| Kassel, Marienkrankenhaus | 257 |

| Hannover, Klinikum Siloah-Oststadt-Heidehaus | 252 |

| Stuttgart, Krankenhaus vom Roten Kreuz | 236 |

| Berlin, Charité Mitte Universitätsmedizin | 227 |

| Immenhausen, Lungenfachklinik | 223 |

| Bad Ems, Hufeland-Klinik | 219 |

| Köln, Kliniken der Stadt Köln | 212 |

| Donaustauf, Klinik | 211 |

| Löwenstein, Klinik | 210 |

| Frankfurt, Bürgerhospital und Clementine Kinderhospital | 209 |

| Lüdenscheid, Klinikum | 197 |

| Bovenden-Lenglern, Evangelisches Krankenhaus | 195 |

| Gauting, Asklepios Fachkliniken | 184 |

| Bremen, Klinikum Bremen-Ost | 175 |

| Bremerhaven, Klinik am Bürgerpark | 173 |

| Herne, Ev, Krankenhaus/Thoraxzentrum Ruhrgebiet | 160 |

| St, Blasien, Klinik | 147 |

| Heidelberg, Thoraxklinik | 142 |

| Ballenstedt, Lungenklinik | 135 |

| Aachen, Universitätsklinikum | 130 |

| Ansbach, Rangauklinik | 125 |

| Aachen, Franziskushospital | 124 |

| Greifenstein, Pneumologische Klinik | 109 |

| Schleswig, Helios Klinikum | 94 |

| Halle, Krankenhaus Martha-Maria | 91 |

| Hofheim, Kliniken des Main Taunus Kreises | 91 |

| Berlin, Brandenburg Klinik | 91 |

| Oberhausen, Johanniter Krankenhaus | 88 |

| Borstel, Medizinische Klinik | 83 |

| Bad Wildungen, Asklepios Kliniken | 79 |

| Duisburg, Bethesda Krankenhaus | 68 |

| Rosenheim, RoMed Klinikum | 68 |

| Lemgo, Klinikum Lippe | 66 |

| Freiburg, Universitätsklinikum | 63 |

| Berlin, Vivantes Klinikum Neukölln | 63 |

| Kehl, Ortenau Klinikum | 52 |

| Lostau, Lungenklinik | 46 |

| Tübingen, Universitätsklinikum | 43 |

| Coswig, Fachkrankenhaus | 41 |

| Chemnitz, Klinikum | 38 |

| Diekholzen, Lungenklinik | 37 |

| Uelzen, Klinikum Uelzen | 37 |

| Oldenburg, Sana Klinik | 35 |

| Würselen, Medizinisches Zentrum StädteRegion Aachen | 34 |

| Flensburg, Malteser Krankenhaus St, Franziskus | 32 |

| Ibbenbüren, Krankenhaus Ibbenbüren | 32 |

| Dorsten, St, Elisabeth-Krankenhaus | 30 |

| Emden, Klinikum Emden | 27 |

| Bad Saarow, Helios Klinikum | 25 |

| Leverkusen, St, Remigius Krankenhaus Opladen | 20 |

| München, Klinikum Harlaching | 15 |

| Waren, Klinik Amsee | 11 |

| Düsseldorf, Florence-Nightingale-Krankenhaus | 9 |

| Bergisch Gladbach, Evangelisches Krankenhaus | 7 |

| Goch, Wilhelm-Anton-Hospital | 6 |

| Mannheim, Theresienkrankenhaus | 6 |

| Göppingen, Klinik am Eichert | 5 |

| Seeheim, Kreisklinik Jugenheim | 5 |

| Speyer, St-,Vincentius Krankenhaus | 3 |

| Schwedt/Oder, Asklepios Klinikum Uckermark | 3 |

| Berlin, Helios Klinikum Berlin-Buch | 3 |

| Freiburg, St, Josefskrankenhaus | 3 |

| Homburg, Universitätklinikum des Saarlandes | 2 |

| Würzburg, Missionsärztliche Klinik GmbH | 2 |

| Kempten, Klinikverbund Kempten-Oberallgäu | 2 |

| Mainz, Katholisches Klinikum | 1 |

| Essen, Alfried Krupp Krankenhaus Steele | 1 |

| Marl, Klinikum Vest | 1 |

| Köln, St, Marien-Hospital | 1 |

| Total | 11 424 |

Weaning outcome

Demographic data are provided in Tables 1. Further data on comorbidities at admission and on mechanical ventilation are given in eTables 2 and 3, respectively.

Table 1. Demographic data and initial reason for mechanical ventilation.

| Demographic parameter | % (median)* |

| Age (years) | 71.0 (63.0–77.0) |

| Sex – female (%) | 38.1 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.1 (23.0–30.9) |

| Smokers (%) | |

| – Current | 22.7 |

| – Former | 52.1 |

| – Never | 25.2 |

| Pre-existing long-term non-invasive ventilation (%) | 10.9 |

| Duration of invasive ventilation before transfer to weaning center (days) | 23 (14–37) |

| – Acute exacerbation of COPD | 25.7 |

| – Pneumonia | 23.6 |

| – Postoperative ARI | 17.0 |

| – Sepsis | 7.8 |

| – Heart failure | 5.7 |

| – ALI/ARDS | 3.2 |

| – Neuromuscular (acute on chronic) | 1.6 |

| – Obesity hypoventilation syndrome (acute on chronic) | 1.4 |

| – Trauma/burns | 1.2 |

| – Restrictive thoracic (acute on chronic) | 0.6 |

| – Other | 12.2 |

*If not otherwise stated, results expressed as % or median (25th–75th percentiles)

ALI, Acute lung injury; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; ARI, acute respiratory insufficiency;

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ECOG score roughly describes function, activities of daily life, and any dependencies)

eTable 2. Comorbidities at the time of transfer to the weaning center and the ECOG performance status prior to acute respiratory failure given in % of all patients.

| Comorbidities | [%] |

| Left heart failure | 29.5 |

| Interstitial lung disease | 4.9 |

| COPD | 54.2 |

| Restrictive thoracic disease | 6.9 |

| Arterial hypertension | 60.8 |

| Critical illness polyneuropathy | 27.1 |

| Neuromuscular disease | 5.6 |

| Obesity | 28.4 |

| Coronary heart disease | 35.5 |

| Renal failure | 34.7 |

| Diabetes mellitus*1 | 33.2 |

| Immunosuppression/AIDS | 1.3 |

| Oncological/hematological disease | 15.0 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 8.7 |

| Delirium | 18.6 |

| Pneumonia | 51.7 |

| Others*2 | 63.6 |

| ECOG performance status prior to acute respiratory failure [%] | |

| [0] Normal unrestricted disease, as before illness | 25.4 |

| [1] Restricted in physically strenuous activity but ambulatory; able to carry out light or sedentary work, e.g., light housework, office work | 17.6 |

| [2] Ambulatory, capable of all self-care, but unable to work; up and about more than 50% of waking hours | 19.2 |

| [3] Capable of only limited self-care; confined to bed or chair more than 50% of waking hours | 8.1 |

| [4] Completely dependent on care, unable to carry out any self-care; totally confined to bed or chair | 2.6 |

| ECOG performance status missing | 27.1 |

*1 Type 1 and type 2 diabetes

*2 Information provided by the transferring hospital without clear definition of the comorbidities.

ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (the ECOG performance status roughly describes function, activities of daily life, and any dependencies).

eTable 3. Access route, mode and settings of ventilation immediately before the first spontaneous breathing trial.

| Access route for ventilation (%) | |

| Orotracheal intubation | 12.3 |

| Tracheostomy | 87.7 |

| Mode of ventilation (%) | |

| Controlled ventilation | 27.7 |

| Assisted ventilation | 67.7 |

| Missing data | 4.6 |

| Ventilator settings | |

| IPAP (mbar) | 20 (17–24) |

| PEEP (mbar) | 6 (5– 8) |

| Tidal volume (ml) | 514 (435–621) |

| Respiratory rate (per minute) | 18 (15– 22) |

IPAP, Inspiratory positive airway pressure; PEEP, positive end-expiratory pressure

Data expressed as % or median (25th–75th percentiles)

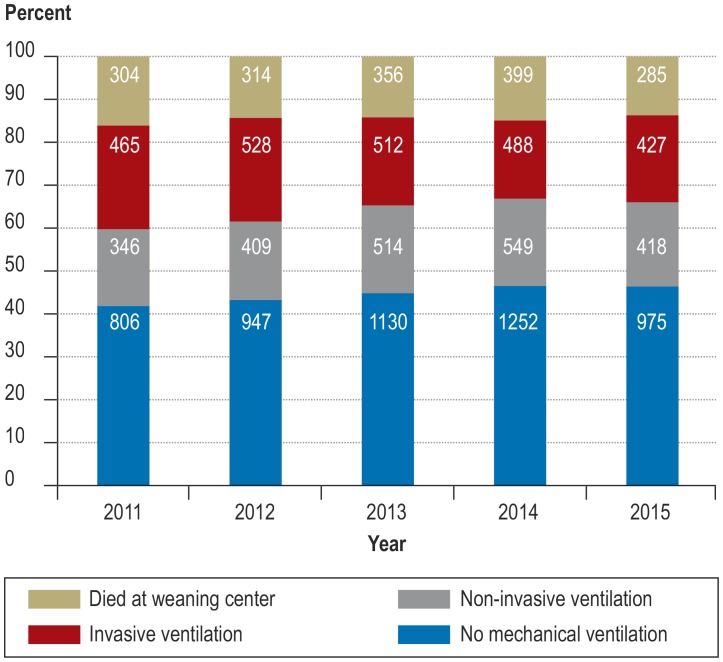

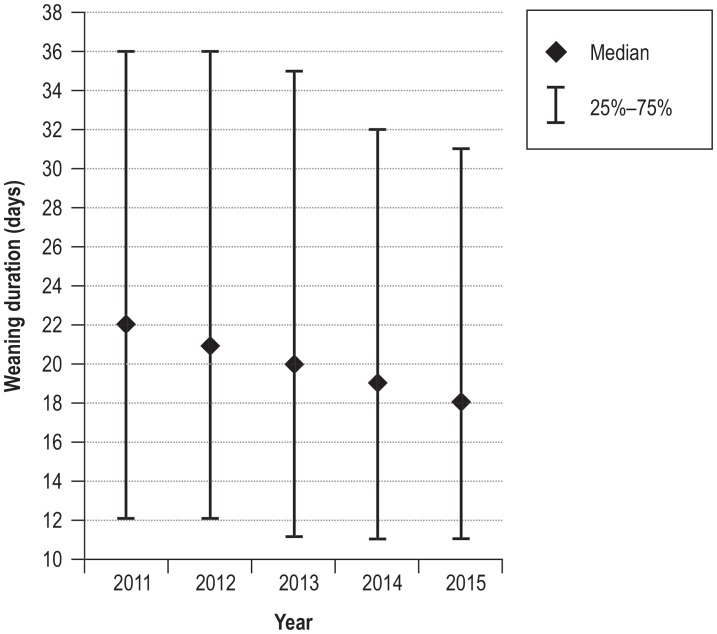

The outcome of weaning changed significantly over the 5-year observation period (chi-squared = 47.4; df = 12; p <0.0001), with a decrease in weaning failure (figure 2). Accordingly, the proportion of patients discharged alive and without invasive community ventilation improved from 60.0% in 2011 to 66.2% in 2015. Furthermore, over the same period there was a significant reduction in weaning duration from 22 days (interquartile range 12–36) to 18 days (interquartile range 11–31) (Kruskal–Wallis H = 67.7; p <0.0001) (efigure 1).

Figure 2.

Changes in weaning outcome between 2011 and 2015 (the absolute numbers of patients are shown in the bars).

eFigure 1.

Change in weaning duration between 2011 and 2015

Factors associated with in-hospital mortality in specialized weaning centers

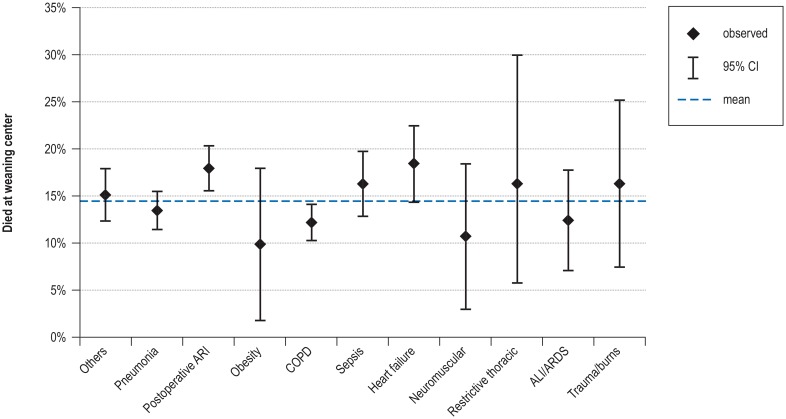

Univariate analysis (total study cohort: N = 11 424) revealed that compared with average in-hospital mortality, patients with postoperative ventilation had a significantly higher mortality rate, while those on mechanical ventilation due to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) had a significantly lower mortality rate (configural frequency analysis [CFA]: p <0.05 (eFigure 2, eMethods). Other factors associated with increased in-hospital mortality were advanced age, higher number of comorbidities, and low tidal volume (eTable 4, eMethods).

eFigure 2.

Influence of the initial reason for ventilation on mortality at the weaning center

ALI, Acute lung injury; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; ARI, acute respiratory insufficiency; CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

eTable 4. Univariate analysis of the factors associated with death at the weaning center, weaning failure, and the need for long-term NIV.

| Died at weaning center | Weaning failure | Initiation of NIV | ||||

| p | OR [95% CI] | p | OR [95% CI] | p | OR [95% CI] | |

| Age at admission (absolute value in years) | 0.0000 | 23.31 [14.95; 36.34] | 0.0000 | 2.40 [1.70; 3.37] | 0.0000 | 0.21 [0.15; 0.30] |

| BMI (absolute value in kg/m2) | 0.0096 | 0.0000 | 0.43 [0.32; 0.58] | 0.0000 | 6.56 [4.87; 8.84] | |

| Duration of invasive ventilation before transfer to weaning center (days) | 0.0615 | 0.0000 | 4.06 [3.03; 5.45] | 0.0021 | ||

| ECOG performance status | 0.5045 | 0.0000 | 3.24 [2.68; 3.91] | 0.0000 | 1.70 [1.38; 2.09] | |

| Number of comorbidities (n) | 0.0000 | 2.30 [1.68; 3.16] | 0.0000 | 1.98 [1.49; 2.61] | 0.0022 | |

| Tidal volume (absolute value in ml) | 0.0001 | 0.32 [0.18; 0.55] | 0.0000 | 0.36 [0.23; 0.58] | 0.6930 | |

| Sex (female) | 0.0022 | 0.0670 | 0.0000 | 1.33 [1.20; 1.48] | ||

| Long-term NIV | 0.0036 | 0.0000 | 2.55 [2.24; 2.90] | 0.0000 | 8.52 [7.05; 10.29] | |

| Left heart failure | 0.0000 | 1.47 [1.32; 1.64] | 0.0031 | 0.6519 | ||

| Interstitial lung disease | 0.0002 | 1.49 [1.21; 1.85] | 0.2648 | 0.0167 | ||

| COPD | 0.0111 | 0.0000 | 1.42 [1.29; 1.56] | 0.0000 | 2.75 [2.48; 3.06] | |

| Restrictive thoracic disease | 0.7257 | 0.0000 | 1.70 [1.43; 2.02] | 0.0004 | 1.46 [1.18; 1.79] | |

| Arterial hypertension | 0.3855 | 0.0039 | 0.0491 | |||

| Critical illness polyneuropathy | 0.0000 | 0.76 [0.67; 0.86] | 0.1701 | 0.0003 | 0.81 [0.72; 0.91] | |

| Neuromuscular disease | 0.2030 | 0.0000 | 2.46 [2.07; 2.93] | 0.5753 | ||

| Obesity | 0.0000 | 0.72 [0.64; 0.81] | 0.0435 | 0.0000 | 1.92 [1.73; 2.13] | |

| Coronary heart disease | 0.0000 | 1.59 [1.43; 1.76] | 0.4200 | 0.0000 | 0.71 [0.64; 0.79] | |

| Renal failure | 0.0000 | 1.85 [1.66; 2.05] | 0.0214 | 0.0000 | 0.79 [0.71; 0.88] | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.4952 | 0.6772 | 0.0032 | |||

| Immunosuppression | 0.3104 | 0.6308 | 0.0017 | 0.41 [0.23; 0.73] | ||

| Oncological/hematological disease | 0.0000 | 1.42 [1.24; 1.63] | 0.1308 | 0.0066 | ||

| Pulmonary hypertension | 0.0217 | 0.0001 | 1.36 [1.16; 1.59] | 0.0000 | 2.00 [1.68; 2.38] | |

| Delirium | 0.2054 | 0.0480 | 0.0000 | 0.64 [0.56; 0.73] | ||

| Pneumonia | 0.0105 | 0.8787 | 0.0000 | 0.81 [0.73; 0.89] | ||

| Other | 0.1305 | 0.2087 | 0.0000 | 0.77 [0.69; 0.85] | ||

The local α-level was adjusted for multiple tests according to the Bonferroni method (p <0.05/25).

Significant results are shown in bold.

OR values <1 are shown in black, OR values > 1 in red.

For continuous parameters, the OR values refer to the maximal range of the parameter from minimum to maximum value; no categorization was undertaken.

CI, Confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (the ECOG performance status roughly describes function, activities of daily life, and any dependencies); NIV, non-invasive ventilation; OR, odds ratio

According to multivariate analysis, the factor most strongly associated with in-hospital mortality was advanced age, followed by low tidal volume and other factors (table 2a).

Table 2a. Factors associated with death at the weaning center; multivariate analysis*.

| Death at weaning center: n = 8339; chi² (8) = 306.04; p <0.0001 | Odds ratio (95% CI) |

| Age at admission (absolute value in years) | 11.07 [6.51; 18.82] |

| Tidal volume (absolute value in ml) | 0.34 [0.19; 0.60] |

| Interstitial lung disease | 1.56 [1.21; 2.00] |

| Critical illness polyneuropathy | 0.65 [0.56; 0.76] |

| Obesity (ever) | 0.71 [0.61; 0.82] |

| Coronary heart disease | 1.32 [1.15; 1.50] |

| Renal failure | 1.68 [1.47; 1.92] |

| Oncological/hematological disease (ever) | 1.38 [1.17; 1.63] |

*Significant parameters are only shown in the final model.

OR values <1 are given in black, OR values > 1 in red.

For continuous parameters, the OR values refer to the maximal range of the parameter from minimum to maximum value; no categorization was undertaken.

Wald‘s Chi-square values and p-values are presented in eTable 5.

CI, Confidence interval

Factors associated with weaning failure

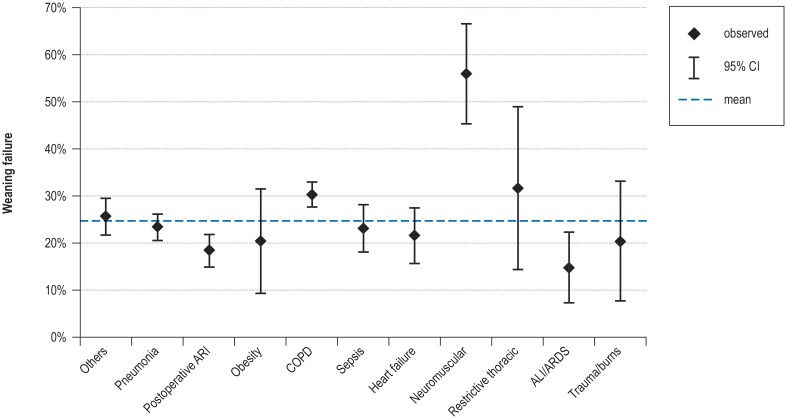

Univariate analysis (hospital survivors: N = 9766) revealed that both COPD patients and those with neuromuscular disorders had significantly higher than average rates of weaning failure, while postoperative patients and those with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) had significantly lower than average weaning failure rates (CFA: p <0.05 (eFigure 3, eMethods). Further analysis demonstrated that the duration of mechanical ventilation before transfer to the weaning unit and high Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status were the variables most strongly associated with unsuccessful weaning (eTable 4, eMethods).

eFigure 3.

Influence of the initial reason for ventilation on weaning failure.

ALI, Acute lung injury; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; ARI, acute respiratory insufficiency; CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

According to multivariate analysis, the factor most strongly associated with unsuccessful weaning was a longer period of mechanical ventilation prior to transfer to the weaning unit, followed by a low body mass index (BMI), pre-existing neuromuscular disorders, advanced age, and others factors (table 2b).

Table 2b. Factors associated with weaning failure; multivariate analysis*.

| Weaning failure: n = 6339; chi² (12) = 391.95; p < 0.0001 | Odds ratio (95% CI) |

| Reason: postoperative ARI | 0.72 [0.59; 0.87] |

| Reason: acute exacerbation of COPD | 1.33 [1.13; 1.56] |

| Reason: neuromuscular (acute on chronic) | 2.98 [1.88; 4.73] |

| Age at admission (absolute value in years) | 2.96 [1.87; 4.69] |

| Body mass index (absolute value in kg/m2) | 0.38 [0.26; 0.58] |

| Duration of invasive ventilation prior to transfer to weaning center (days) | 4.73 [3.25; 6.89] |

| ECOG performance status | 2.17 [1.73; 2.72] |

| Pre-existing long-term non-invasive ventilation | 1.98 [1.64; 2.40] |

| COPD | 1.20 [1.04; 1.40] |

| Restrictive thoracic disease | 1.57 [1.26; 1.95] |

| Neuromuscular disease | 1.87 [1.43; 2.43] |

| Arterial hypertension | 1.29 [1.04; 1.60] |

*Significant parameters are only shown in the final model.

OR values <1 are given in black, OR values > 1 in red.

For continuous parameters, the OR values refer to the maximal range of the parameter from minimum to maximum value; no categorization was undertaken. Wald‘s Chi-square values and p-values are presented in eTable 5.

ARI, Acute respiratory insufficiency; CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (the ECOG performance status roughly describes function, activities of daily life, and any dependencies)

Factors associated with the need for long-term non-invasive ventilation

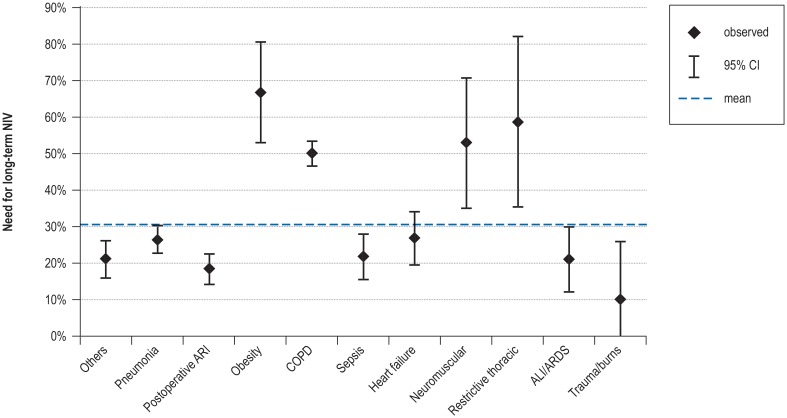

Univariate analysis (successful weaning: [16] N = 7346) revealed that patients with COPD, neuromuscular disorders, obesity hypoventilation syndrome, or restrictive thoracic disorders were significantly more likely to need long-term non-invasive ventilation (CFA: p <0.05 (eFigure 4, eMethods). Further analysis showed that the factors most strongly associated with the initiation/continuation of long-term non-invasive ventilation were identified as pre-existing home mechanical ventilation, high BMI, and young age (eTable 4, eMethods).

eFigure 4.

Influence of the initial reason for mechanical ventilation on the need for long-term NIV.

ALI, Acute lung injury; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; ARI, acute respiratory insufficiency; CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NIV, non-invasive ventilation

According to multivariate analysis, the factors most strongly associated with the need for continuation of non-invasive ventilation were pre-existing non-invasive ventilation, high BMI, and young age, followed by neuromuscular disorders and other factors (table 2c).

Table 2c. Factors associated with the need for long-term NIV; multivariate analysis*.

| Initiation of NIV: n = 7207; chi² (17) = 1357.5; p <0.0001 | Odds ratio (95% CI) |

| Reason: postoperative ARI | 0.77 [0.64; 0.91] |

| Reason: obesity hypoventilation (acute on chronic) | 2.78 [1.76; 4.39] |

| Reason: acute exacerbation of COPD | 1.84 [1.59; 2.14] |

| Reason: neuromuscular (acute on chronic) | 3.64 [2.16; 6.14] |

| Reason: ALI/ARDS | 0.71 [0.51; 0.99] |

| Reason: trauma/burns | 0.36 [0.17; 0.74] |

| Reason: other | 0.76 [0.62; 0.93] |

| Age at admission (absolute value in years) | 0.32 [0.21; 0.49] |

| Body mass index (absolute value in kg/m2) | 3.68 [2.41; 5.63] |

| Pre-existing long-term non-invasive ventilation | 6.28 [5.13; 7.67] |

| COPD | 2.02 [1.77; 2.30] |

| Restrictive thoracic disease | 1.82 [1.44; 2.30] |

| Obesity [ever] | 1.30 [1.12; 1.52] |

| Coronary heart disease | 0.88 [0.77; 0.99] |

| Arterial hypertension | 1.87 [1.54; 2.28] |

| Delirium | 0.70 [0.60; 0.81] |

| Other [ever] | 0.81 [0.72; 0.91] |

*Significant parameters are only shown in the final model.

OR values <1 are given in black, OR values > 1 in red.

For continuous parameters, the OR values refer to the maximal range of the parameter from minimum to maximum value; no categorization was undertaken. Wald‘s Chi-square values and p-values are presented in eTable 5.

ALI, Acute lung injury; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; ARI, acute respiratory insufficiency; CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NIV, non-invasive ventilation

Discussion

This is the first large, national multicenter study to investigate weaning outcome and the associated determining factors in patients with prolonged weaning. Thus, our cohort comprised severely ill patients requiring weaning, a group that had not been sufficiently addressed and characterized in previous trials. The most important findings are as follows:

Prolonged weaning is a clinically significant and prevalent phenomenon in Germany. However, the true incidence of prolonged weaning, cannot be assessed on the basis of the existing data, since in Germany many patients with prolonged weaning are treated in facilities other than specialized weaning centers. Nevertheless, it should be noted that this cohort of patients with prolonged weaning has been markedly under-represented in previous trials, which focused solely on ICU patients. In the most recent epidemiological study from France, only 37 (1.4%) of 2729 patients were tracheostomized and classed as non-weanable [11], against 2420 (21.2%) of 11 424 patients in our study.

Furthermore, about two thirds of patients with prolonged weaning who could not be weaned on the ICU were successfully weaned after transfer to a specialized weaning unit. We also found that the weaning success rate improved over the 5-year observation period. This may represent a learning curve, although changes in patient selection cannot be excluded with certainty. Thus, the establishment of specialized weaning centers based on clearly defined requirements seems warranted, although this needs to be further verified by future studies using a prospective approach.

This study defined factors associated with weaning outcome: The factor most strongly associated with in-hospital mortality on the weaning unit was advanced age of the patient. Other factors, including the duration of mechanical ventilation on the transferring ICU, low BMI, pre-existing neuromuscular disorders, and advanced age, were also strongly associated with weaning failure in patients who survived their stay in hospital. Finally, several factors were found to be associated with the need to continue non-invasive ventilation in the long term after hospital discharge, the most important being pre-existing long-term non-invasive ventilation, obesity hypoventilation syndrome, neuromuscular disorders, and younger age.

This analysis has important clinical implications. First, in patients requiring intensive care it has to be anticipated that weaning from mechanical ventilation may be considerably delayed or even impossible in the case of advanced age or the presence of conditions that predispose to chronic respiratory insufficiency. Second, the results of this study argue in favor of the establishment of weaning centers devoted to this specific subset of patients, since it has been postulated that there will be a steady increase in the complexity and severity of the underlying conditions in ICU patients, potentiating the likelihood of unsuccessful weaning [22]. This is extremely important in view of the steadily increasing number of patients with community ventilation in Germany [21]. This study has shown that the time spent on the ventilator in the ICU is negatively associated with weaning success. This association was also found in a recent small single-center study [23]. Early transfer of the patient to a specialized weaning unit thus seems justifiable, although this aspect was not specifically addressed in our study.

Despite the successful results achieved in specialized weaning centers, 25% of patients who did not die in the weaning unit could not be weaned and were discharged to long-term invasive ventilation in the community. However, the continuation of invasive ventilation in a community setting subsequent to weaning failure is associated with severe impairments in health-related quality of life, especially in patients with COPD; this may well raise ethical concerns with regard to current ICU treatment practices [24,25]. Moreover, the present study has identified clinical parameters that are associated with weaning failure. This may facilitate the decision-making process on the ICU, but further prospective investigations are needed in this regard. Undoubtedly this would initiate an ethical debate on the exact circumstances under which mechanical ventilation should be implemented. Self-evidently, the precise circumstances of the individual patient must always be taken into account.

This study has some limitations, mostly related to patient selection. First, the data refer primarily to patients with prolonged weaning who were transferred to specialized weaning centers. The findings therefore cannot be extrapolated to patients with prolonged weaning who remain on the ICU that provided the initial treatment. In this regard, it should be noted that there were no predefined criteria for or against transfer to a weaning center. This partially limits the generalizability of the findings. Nevertheless, it should be emphasized that the high numbers of patients and centers broadly reflect clinical reality. Second, although patients were treated at weaning centers, it cannot be ruled out that some patient data were not registered. Specifically, patients had to provide informed written consent for inclusion of their data in the registry; it thus seems unlikely that the data of the most severely ill patients, who died early in the course of their treatment, are all included in the weaning registry. Moreover, although plausibility analyses was performed according to predefined criteria, source data verification was not possible in all cases. The limits of plausibility were set arbitrarily, and data correctness for values within these limits could not be guaranteed. Third, the plausibility analyses led to exclusion of some patients from analysis due to inconsistencies in dates and classification, but the absence of these cases (with the consequence of incomplete data sets) may have reduced statistical strength. Fourth, data from the transferring ICU were only sparsely available, which may have prevented more detailed analysis. For example, the true weaning duration in the transferring hospital could not be documented. Finally, we did not address the status of patients who were transferred from the weaning center to another hospital.

In conclusion, patients with prolonged weaning who are transferred to a specialized weaning center following several weeks of invasive ventilation on the ICU represent an epidemiologically important subset of weaning patients that has not been sufficiently characterized by previous studies. In this setting, although the outcome of weaning is still significantly restricted, it has continued to improve over time. The establishment of variables associated with hospital mortality and weaning failure may be helpful in designing future studies on decision-making processes in intensive care medicine.

Supplementary Material

eMethods

Ethics committee approval

Data of the WeanNet registry for the period 1 January 2011 to 1 January 2016 were analyzed. Although data collection was carried out prospectively for the purpose of the accreditation of German weaning centers, all analyses were performed exploratively without predefined hypotheses. Accordingly, the study was not registered with at any clinical trials registry. The study was approved by the ethics committee of Witten/Herdecke University. In addition, all documentation was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed written consent was prospectively obtained from all subjects or their authorized representatives.

Weaning centers and weaning registry: WeanNet

In Germany, weaning centers with a special focus on prolonged weaning are accredited according to criteria laid down by the German Respiratory Society (DGP). One of the requirements of the accreditation process is the collection of data from patients who require weaning, with the aim of achieving high-quality results. Detailed accreditation criteria can be found on the DGP website (26).

Briefly, the general criteria for accreditation stipulate a staged treatment approach: the patients are treated on a special weaning unit but also have direct access both to the ICU and to a special unit for the treatment of patients with community mechanical ventilation. Moreover, the chief physician must possess expertise in respiratory medicine. Detailed criteria for the structure of the weaning units, technical aspects, the interdisciplinary treatment team, and treatment processes are given below.

The WeanNet registry started in March 2008. In the months thereafter, the data base was tested and refined, and all contributing centers received special training in how to enter the data. This process was concluded in December 2010. Thus, for the purpose of the study, data between 1 January 2011 and 1 January 2016 were analyzed. Eighty-five centers with a specialized weaning unit participated (etable 1). Among these centers, 14 were already accredited in 2011, 18 were accredited during the study period, and 53 were still undergoing the accreditation process at the end of the study period.

The WeanNet registry data comprise around 140 variables, divided into six categories:

Weaning success was defined as discharge from the weaning center without the need for continuation of invasive ventilation. Weaning duration was recorded only in surviving patients and referred to the period of treatment in the weaning center; any phases of weaning in the transferring intensive care unit were not considered. In-hospital mortality referred exclusively to deaths occurring in the weaning center.

Data management

The following steps of encoding, recoding, and calculation of additional variables were performed before starting the statistical analysis:

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by data-quest GmbH in close collaboration with the DGP. The results were expressed as median and quartiles. If not otherwise stated, two-tailed testing was carried out and a p-value less than 0.05 was considered to be significant. All data were analyzed using the sotware STATISTICA, version 10. Changes in weaning success (mortality, weaning duration) over the course of time between 2011 and 2015 were evaluated using the chi-square test and Kruskal–Wallis non-parametric analysis of variance, respectively.

Univariate analysis was performed using three distinct dependent variables:

The dependency of each of these variables on the initial reason for acute ventilation was investigated by means of configural frequency analysis, a method based on chi-square tests.

For comorbidities, odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals were calculated. This was performed in a similar fashion for the continuous parameters. The stated odds ratios refer to the difference between the two extreme values, minimum and maximum, for each parameter; no categorization was undertaken. The local level was adjusted for multiple tests according to the Bonferroni method (p <0.05/25). In addition to the impact of the individual comorbidities, the total number of comorbidities per patient was also analyzed.

Multivariate analysis was performed with three distinct binary logistic regressions (logit model). The quasi-Newton method and Rosenbrock’s function were used for parameter estimation, starting with the parameters found to be significant in univariate analysis and then eliminating parameters step by step until only significant variables were contained in the final model.

Admission (inclusion criteria, initiation of invasive ventilation, route and mode of ventilation)

Medical history (reason for ventilation, comorbidities, smoking status, previous phases of ventilation)

Course of weaning (ventilation parameters, spontaneous breathing trials, results of blood gas analysis, end of weaning)

Complications

Discharge (outcome, classification)

Follow-up (long-term survival, community ventilation, readmissions)

The variables ECOG (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status—see eTable 2) before the acute illness and ECOG after the acute illness were encoded from a composite text into a numerical value.

The variable diagnosis/comorbidities was divided into 17 distinct variables, one for each different diagnosis using 1/0 encoding. An additional variable, number of comorbidities, was included.

The variable duration of first SBT (spontaneous breathing trial) in the weaning unit, recorded in a mixture of hours and minutes, was consistently converted to minutes.

The variable hemoglobin during first SBT in the weaning unit, recorded in a mixture of g/dl and mmol/l, was consistently converted to g/dl.

The variables IPAP (inspiratory positive airway pressure) and PEEP (positive end expiratory pressure), recorded in a mixture of mbar and cmH2O, were consistently converted to mbar.

A new variable, duration of previous ventilation, was calculated as admission date – initiation of mechanical ventilation.

A new variable, duration of weaning process, was calculated as weaning process concluded on – admission date.

A new variable, length of stay in weaning unit, was calculated as „date of discharge from weaning unit – admission date.

A new variable, outcome, was constructed by combining the variables died in weaning center and status at conclusion of treatment.

The risk of dying at the weaning center

The risk of remaining dependent on invasive ventilation

The risk of needing long-term non-invasive ventilation

Key Messages.

Specialized weaning centers with a focus on the management of prolonged weaning are established according to criteria laid down by the German Respiratory Society, one of the requirements of the accreditation process being documentation in a weaning registry.

This study evaluated the data entered in the registry between 2011 and 2016 (total: 11 424 patients). Almost two thirds of patients who could not be weaned on the transferring intensive care units were subsequently successfully weaned in the specialized centers.

Advanced age was the factor associated most strongly with in-hospital mortality, while an extended period of mechanical ventilation in the intensive care unit prior to transfer was the factor associated most closely with unsuccessful weaning.

There are still no reliable data on the number of patients in Germany who are discharged to continue invasive ventilation in the community without first being transferred to a specialized weaning center.

It seems reasonable to transfer all patients thought to be unweanable on the intensive care unit to a specialized weaning center in order to exploit the full weaning potential.

eTable 5. Multivariate analysis of the factors associated with death at the weaning center, weaning failure and the need for long-term NIV.

| Wald‘s chi-square | P | Odds ratio [95% CI] | |

| In-hospital mortality: n = 8339; chi² (8) = 306.04; p < 0.0001 | |||

| Age at admission (absolute value in years) | 78.7350 | 0.0000 | 11.07 [6.51; 18.82] |

| Tidal volume(absolute value in ml) | 13.7646 | 0.0002 | 0.34 [0.19; 0.60] |

| Interstitial lung disease | 11.9879 | 0.0005 | 1.56 [1.21; 2.00] |

| Critical illness polyneuropathy | 30.7911 | 0.0000 | 0.65 [0.56; 0.76] |

| Obesity (ever) | 20.3116 | 0.0000 | 0.71 [0.61; 0.82] |

| Coronary heart disease | 16.6748 | 0.0000 | 1.32 [1.15; 1.50) |

| Renal failure | 59.0255 | 0.0000 | 1.68 [1.47; 1.92] |

| Oncological/hematological disease (ever) | 14.3753 | 0.0002 | 1.38 [1.17; 1.63] |

| Weaning failure: n = 6339; chi² (12) = 391.95; p < 0.0001 | |||

| Reason: postoperative ARI | 11.7699 | 0.0006 | 0.72 [0.59; 0.87] |

| Reason: acute exacerbation of COPD | 12.0867 | 0.0005 | 1.33 [1.13; 1.56] |

| Reason: neuromuscular (acute on chronic) | 21.7264 | 0.0000 | 2.98 [1.88; 4.73] |

| Age at admission (absolute value in years) | 21.6143 | 0.0000 | 2.96 [1.87; 4.69] |

| Body mass index (absolute value in kg/m2) | 21.3490 | 0.0000 | 0.38 [0.26; 0.58] |

| Duration of invasive ventilation before transfer to weaning center (days) | 65.9623 | 0.0000 | 4.73 [3.25; 6.89] |

| ECOG performance status | 45.8064 | 0.0000 | 2.17 [1.73; 2.72] |

| Pre-existing long-term non-invasive ventilation | 49.5668 | 0.0000 | 1.98 [1.64; 2.40] |

| COPD | 6.0590 | 0.0138 | 1.20 [1.04; 1.40] |

| Restrictive thoracic disease | 15.9438 | 0.0001 | 1.57 [1.26; 1.95] |

| Neuromuscular disease | 21.4888 | 0.0000 | 1.87 [1.43; 2.43] |

| Arterial hypertension | 5.3314 | 0.0210 | 1.29 [1.04; 1.60] |

| Initiation of NIV: n = 7207; chi² (17) = 1357.5; p < 0.0001 | |||

| Reason: postoperative ARI | 8.9055 | 0.0028 | 0.77 [0.64; 0.91] |

| Reason: obesity hypoventilation (acute on chronic) | 19.3283 | 0.0000 | 2.78 [1.76; 4.39] |

| Reason: acute exacerbation of COPD | 64.6147 | 0.0000 | 1.84 [1.59; 2.14] |

| Reason: neuromuscular (acute on chronic) | 23.4927 | 0.0000 | 3.64 [2.16; 6.14] |

| Reason: ALI/ARDS | 4.0324 | 0.0446 | 0.71 [0.51; 0.99] |

| Reason: Trauma/burns | 7.6559 | 0.0057 | 0.36 [0.17; 0.74] |

| Reason: Others | 7.2008 | 0.0073 | 0.76 [0.62; 0.93] |

| Age at admission (absolute value in years) | 27.9406 | 0.0000 | 0.32 [0.21; 0.49] |

| Body mass index (absolute value in kg/m2) | 36.1524 | 0.0000 | 3.68 [2.41; 5.63] |

| Pre-existing long-term non-invasive ventilation | 321.2916 | 0.0000 | 6.28 [5.13; 7.67] |

| COPD | 108.4588 | 0.0000 | 2.02 [1.77; 2.30] |

| Restrictive thoracic disease | 24.6761 | 0.0000 | 1.82 [1.44; 2.30] |

| Obesity (ever) | 11.5340 | 0.0007 | 1.30 [1.12; 1.52] |

| Coronary heart disease | 4.3049 | 0.0380 | 0.88 [0.77; 0.99] |

| Arterial hypertension | 39.6919 | 0.0000 | 1.87 [1.54; 2.28] |

| Delirium | 22.2039 | 0.0000 | 0.70 [0.60; 0.81] |

| Others (ever) | 12.1258 | 0.0005 | 0.81 [0.72; 0.91] |

Significant parameters are only shown in the final model.

OR values <1 are given in black, OR values > 1 in red.

For continuous parameters, the OR values refer to the maximal range of the parameter from minimum to maximum value; no categorization was undertaken.

ALI, Acute lung injury; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; ARI, acute respiratory insufficiency; CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; NIV, non-invasive ventilation; OR, odds ratio

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by the German Respiratory Society (DGP). The authors would like to thank S. Dieni for editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement Prof Windisch’s study group has received research grants from Weinmann, Vivisol, Heinen und Löwenstein, VitalAire (all Germany), and Philips Respironics (USA). Prof Windisch has received speaking fees from Löwenstein and ResMed.

Dr. Geiseler has received speaking fees from Löwenstein, Philips, and Berlin-Chemie.

Prof. Pfeifer has received speaking fees from ResMed.

Herr Suchi has received research grants from the German Respiratory Society (DGP) for statistical analyses.

Prof. Schönhofer is first author of the German consensus-based guideline “Prolonged Weaning.”

The remaining authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.McConville JF, Kress JP. Weaning patients from the ventilator. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2233–2239. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1203367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boles JM, Bion J, Connors A, et al. Weaning from mechanical ventilation. Eur Respir J. 2007;29:1033–1056. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00010206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Epstein SK, Ciubotaru RL. Independent effects of etiology of failure and time to reintubation on outcome for patients failing extubation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158:489–493. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.2.9711045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thille AW, Richard J-CM, Brochard L. The decision to extubate in the intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:1294–1302. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201208-1523CI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peñuelas O, Frutos-Vivar F, Fernández C, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of ventilated patients according to time to liberation from mechanical ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:430–437. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201011-1887OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tonnelier A, Tonnelier J-M, Nowak E, et al. Clinical relevance of classification according to weaning difficulty. Respir Care. 2011;56:583–590. doi: 10.4187/respcare.00842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sellares J, Ferrer M, Cano E, et al. Predictors of prolonged weaning and survival during ventilator weaning in a respiratory ICU. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37:775–784. doi: 10.1007/s00134-011-2179-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Funk GC, Anders S, Breyer MK, et al. Incidence and outcome of weaning from mechanical ventilation according to new categories. Eur Respir J. 2010;35:88–94. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00056909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pu L, Zhu B, Jiang L, et al. Weaning critically ill patients from mechanical ventilation: a prospective cohort study. J Crit Care. 2015;30:862.e7–86213. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2015.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jeong BH, Ko MG, Nam J, Yoo H, et al. Differences in clinical outcomes according to weaning classifications in medical intensive care units. Plos One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122810. e0122810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schönhofer B, Euteneuer S, Nava S, et al. Survival of mechanically ventilated patients admitted to a specialised weaning centre. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28:908–916. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1287-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Béduneau G, Pham T, Schortgen F, et al. Epidemiology of weaning outcome according to a new definition The WIND Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:772–783. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201602-0320OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Windisch W, Geiseler J, Simon K, et al. German national guideline for treating chronic respiratory failure with invasive and non-invasive ventilation: Revised edition 2017 - Part 1. Respiration. 2018;96:66–97. doi: 10.1159/000488001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Windisch W, Geiseler J, Simon K, et al. German national guideline for treating chronic respiratory failure with invasive and non-Invasive ventilation Revised edition 2017: Part 2. Respiration. 2018;96:171–203. doi: 10.1159/000488667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hannan LM, Tan S, Hopkinson K, et al. Inpatient and long-term outcomes of individuals admitted for weaning from mechanical ventilation at a specialized ventilation weaning unit. Respirology. 2013;18:154–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2012.02266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schönhofer B, Geiseler J, Dellweg D, et al. Prolongiertes Weaning - S2k-Leitlinie Deutschen Gesellschaft für Pneumologie und Beatmungsmedizin (eds) Pneumologie. 2019;73:723–814. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davies MG, Quinnell TG, Oscroft NS, et al. Hospital outcomes and long-term survival after referral to a specialized weaning unit. Br J Anaesth. 2017;118:563–569. doi: 10.1093/bja/aex031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scheinhorn DJ, Chao DC, Stearn-Hassenpflug M, et al. Post-ICU mechanical ventilation: treatment of 1123 patients at a regional weaning center. Chest. 1997;111:1654–1659. doi: 10.1378/chest.111.6.1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scheinhorn DJ, Hassenpflug MS, Votto JJ, et al. Post-ICU mechanical ventilation at 23 long-term care hospitals: a multicenter outcomes study. Chest. 2007;131:85–93. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schönhofer B, Geiseler J, Pfeifer M, et al. WeanNet: a network of weaning units headed by pneumologists. Pneumologie. 2014;68:737–742. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1377956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karagiannidis C, Strassmann S, Callegari J, et al. Epidemiologische Entwicklung der außerklinischen Beatmung: Eine rasant zunehmende Herausforderung für die ambulante und stationäre Patientenversorgung. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2019;144:e58–e63. doi: 10.1055/a-0758-4512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Polverino E, Nava S, Ferrer M, et al. Patients‘ characterization. hospital course and clinical outcomes in five Italian respiratory intensive care units. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36:137–142. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1658-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Magnet MS, Bleichroth H, Huttmann SE, et al. Clinical evidence for respiratory pump insufficiency predicts weaning failure in long-term ventilated, tracheotomised patients: a retrospective analysis. J Intensive Care. 2018;16:6–67. doi: 10.1186/s40560-018-0338-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huttmann SE, Windisch W, Storre JH. Invasive home mechanical ventilation: living conditions and health-related quality of life. Respiration. 2015;89:312–321. doi: 10.1159/000375169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huttmann SE, Magnet FS, Karagiannidis C, et al. Quality of life and life satisfaction are severely impaired in patients with long-term invasive ventilation following ICU treatment and unsuccessful weaning. Ann Intensive Care. 2018;8 doi: 10.1186/s13613-018-0384-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deutsche Gesellschaft für Pneumologie und Beatmungsmedizin e. V. Erhebungsbogen zur Zertifizierung von Weaning-Zentren. https://pneumologie.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Erhebungsbogen_zur_Zertifizierung_Weaning-Zentren_Version_06.pdf (last accessed on 10 February 2020) [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods

Ethics committee approval

Data of the WeanNet registry for the period 1 January 2011 to 1 January 2016 were analyzed. Although data collection was carried out prospectively for the purpose of the accreditation of German weaning centers, all analyses were performed exploratively without predefined hypotheses. Accordingly, the study was not registered with at any clinical trials registry. The study was approved by the ethics committee of Witten/Herdecke University. In addition, all documentation was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed written consent was prospectively obtained from all subjects or their authorized representatives.

Weaning centers and weaning registry: WeanNet

In Germany, weaning centers with a special focus on prolonged weaning are accredited according to criteria laid down by the German Respiratory Society (DGP). One of the requirements of the accreditation process is the collection of data from patients who require weaning, with the aim of achieving high-quality results. Detailed accreditation criteria can be found on the DGP website (26).

Briefly, the general criteria for accreditation stipulate a staged treatment approach: the patients are treated on a special weaning unit but also have direct access both to the ICU and to a special unit for the treatment of patients with community mechanical ventilation. Moreover, the chief physician must possess expertise in respiratory medicine. Detailed criteria for the structure of the weaning units, technical aspects, the interdisciplinary treatment team, and treatment processes are given below.

The WeanNet registry started in March 2008. In the months thereafter, the data base was tested and refined, and all contributing centers received special training in how to enter the data. This process was concluded in December 2010. Thus, for the purpose of the study, data between 1 January 2011 and 1 January 2016 were analyzed. Eighty-five centers with a specialized weaning unit participated (etable 1). Among these centers, 14 were already accredited in 2011, 18 were accredited during the study period, and 53 were still undergoing the accreditation process at the end of the study period.

The WeanNet registry data comprise around 140 variables, divided into six categories:

Weaning success was defined as discharge from the weaning center without the need for continuation of invasive ventilation. Weaning duration was recorded only in surviving patients and referred to the period of treatment in the weaning center; any phases of weaning in the transferring intensive care unit were not considered. In-hospital mortality referred exclusively to deaths occurring in the weaning center.

Data management

The following steps of encoding, recoding, and calculation of additional variables were performed before starting the statistical analysis:

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by data-quest GmbH in close collaboration with the DGP. The results were expressed as median and quartiles. If not otherwise stated, two-tailed testing was carried out and a p-value less than 0.05 was considered to be significant. All data were analyzed using the sotware STATISTICA, version 10. Changes in weaning success (mortality, weaning duration) over the course of time between 2011 and 2015 were evaluated using the chi-square test and Kruskal–Wallis non-parametric analysis of variance, respectively.

Univariate analysis was performed using three distinct dependent variables:

The dependency of each of these variables on the initial reason for acute ventilation was investigated by means of configural frequency analysis, a method based on chi-square tests.

For comorbidities, odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals were calculated. This was performed in a similar fashion for the continuous parameters. The stated odds ratios refer to the difference between the two extreme values, minimum and maximum, for each parameter; no categorization was undertaken. The local level was adjusted for multiple tests according to the Bonferroni method (p <0.05/25). In addition to the impact of the individual comorbidities, the total number of comorbidities per patient was also analyzed.

Multivariate analysis was performed with three distinct binary logistic regressions (logit model). The quasi-Newton method and Rosenbrock’s function were used for parameter estimation, starting with the parameters found to be significant in univariate analysis and then eliminating parameters step by step until only significant variables were contained in the final model.

Admission (inclusion criteria, initiation of invasive ventilation, route and mode of ventilation)

Medical history (reason for ventilation, comorbidities, smoking status, previous phases of ventilation)

Course of weaning (ventilation parameters, spontaneous breathing trials, results of blood gas analysis, end of weaning)

Complications

Discharge (outcome, classification)

Follow-up (long-term survival, community ventilation, readmissions)

The variables ECOG (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status—see eTable 2) before the acute illness and ECOG after the acute illness were encoded from a composite text into a numerical value.

The variable diagnosis/comorbidities was divided into 17 distinct variables, one for each different diagnosis using 1/0 encoding. An additional variable, number of comorbidities, was included.

The variable duration of first SBT (spontaneous breathing trial) in the weaning unit, recorded in a mixture of hours and minutes, was consistently converted to minutes.

The variable hemoglobin during first SBT in the weaning unit, recorded in a mixture of g/dl and mmol/l, was consistently converted to g/dl.

The variables IPAP (inspiratory positive airway pressure) and PEEP (positive end expiratory pressure), recorded in a mixture of mbar and cmH2O, were consistently converted to mbar.

A new variable, duration of previous ventilation, was calculated as admission date – initiation of mechanical ventilation.

A new variable, duration of weaning process, was calculated as weaning process concluded on – admission date.

A new variable, length of stay in weaning unit, was calculated as „date of discharge from weaning unit – admission date.

A new variable, outcome, was constructed by combining the variables died in weaning center and status at conclusion of treatment.

The risk of dying at the weaning center

The risk of remaining dependent on invasive ventilation

The risk of needing long-term non-invasive ventilation