Abstract

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization declared that COVID-19 was a pandemic.1 At that time, only 118,000 cases had been reported globally, 90% of which had occurred in 4 countries.1 Since then, the world landscape has changed dramatically. As of March 31, 2020, there are now nearly 800,000 cases, with truly global involvement.2 Countries that were previously unaffected are currently experiencing mounting rates of the novel coronavirus infection with associated increases in COVID-19–related deaths. At present, Canada has more than 8000 cases of COVID-19, with considerable variation in rates of infection among provinces and territories.3 Amid concerns over growing resource constraints, cardiac surgeons from across Canada have been forced to make drastic changes to their clinical practices. From prioritizing and delaying elective cases to altering therapeutic strategies in high-risk patients, cardiac surgeons, along with their heart teams, are having to reconsider how best to manage their patients. It is with this in mind that the Canadian Society of Cardiac Surgeons (CSCS) and its Board of Directors have come together to formulate a series of guiding statements. With strong representation from across the country and the support of the Canadian Cardiovascular Society, the authors have attempted to provide guidance to their colleagues on the subjects of leadership roles that cardiac surgeons may assume during this pandemic: patient assessment and triage, risk reduction, and real-time sharing of expertise and experiences.

Résumé

Le 11 mars 2020, l’Organisation mondiale de la Santé a déclaré que l’épidémie de COVID-19 était une pandémie1. À ce moment, on rapportait seulement 118 000 cas à l’échelle mondiale, dont 90 % s’étaient déclarés dans quatre pays1. Depuis, la situation dans le monde a radicalement changé. Au 31 mars 2020, on comptait près de 800 000 cas répartis partout dans le monde2. Des pays qui n’avaient jusque-là pas été touchés voient le nombre de nouveaux cas d’infection monter en flèche, les décès liés à la COVID-19 augmentant par le fait même. À l’heure actuelle, plus de 8 000 cas de COVID-19 ont été rapportés au Canada, les taux d’infection variant considérablement d’une province et d’un territoire à l’autre3. En raison de préoccupations quant aux ressources de plus en plus limitées, les chirurgiens en cardiologie du Canada ont dû modifier radicalement leurs pratiques cliniques. Avec l’aide des leurs équipes de cardiologie, les chirurgiens en cardiologie doivent réévaluer leurs méthodes afin de prendre en charge le mieux possible leurs patients, notamment en établissant l’ordre de priorité des cas, en reportant le traitement des cas non urgents et en modifiant leurs stratégies thérapeutiques auprès des patients présentant un risque élevé. C’est dans ce contexte que la Société canadienne des chirurgiens cardiaques et son conseil d’administration ont entrepris de formuler un ensemble de déclarations directrices. Les auteurs, qui proviennent de partout au pays et qui ont bénéficié du soutien de la Société canadienne de cardiologie, ont tenté de formuler des recommandations à l’intention de leurs confrères et consœurs pour les aider à assumer le rôle de leader qu’ils sont appelés à jouer durant la pandémie, notamment en matière d’évaluation et de triage des patients, d’atténuation des risques et de partage de leur expertise et de leurs expériences en temps réel.

As the number of COVID-19 cases continues to increase across Canada, the Canadian Society of Cardiac Surgeons (CSCS) and its Board of Directors strongly support the need to contain COVID-19 and to limit its transmission through social distancing, self-isolation, and self-quarantine, as directed by the public health authorities. We also fully endorse the efforts taken at every level of the health care system (hospital, local health authority, provincial department of health, federal health ministry) to prepare for the potential surge in patients with COVID-19 and any clinical needs that may come as a result.

Unfortunately, few have been able to estimate accurately the extent to which COVID-19 will affect the population of Canada in terms of rates of incidence, duration, and recovery. Even less is known about how the impact of COVID-19 will vary from hospital to hospital and from province to province. Amid all this uncertainty, cardiac surgeons from across the country are being required to scale back their clinical practices in anticipation of an eventual scarcity of resources, including shortages in personal protective equipment (PPE); surgical drapes; mechanical ventilators; extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) circuits; and, ultimately, health care personnel. Despite this, cardiac surgeons now—more than ever before—have an incredibly valuable role to play during these challenging times.

The CSCS believes that it is imperative that cardiac surgeons maintain an active leadership role on health care teams during this pandemic and contribute their skill sets, both within and outside their traditional scopes of practice. A visual abstract of the main principles underlying our recommended approach is provided in Figure 1. To this effect, the CSCS has proposed the following guiding statements in an effort to guide cardiac surgeons over the short term, as the COVID-19 pandemic continues to unfold:

-

1.

Cardiac surgeons should be actively engaged in the emergency response teams of their respective institutions during the pandemic response.

-

2.

The first priority of the cardiac surgery team is to ensure that the cardiac surgery needs of the hospital, the health region, and—in certain instances—the province, are met within the context of the COVID-19 burden within their jurisdictions. However, cardiac surgeons, in this time of need, should also be willing to take on additional responsibilities, including—but not limited to—performing noncardiac surgery, caring for nonsurgical cardiovascular patients, and caring for critically ill patients irrespective of their COVID-19 status.

-

3.

Cardiac surgeons should be involved in regular discussions with their administrations, cardiology colleagues, and critical care colleagues to evaluate resource availability to ensure the appropriate utilization of potentially scarce resources including—but not limited to—ward and intensive care unit beds, ventilators, ECMO circuits, operating rooms, equipment, drapes, PPE, medications, blood products, and health care personnel.

-

4.

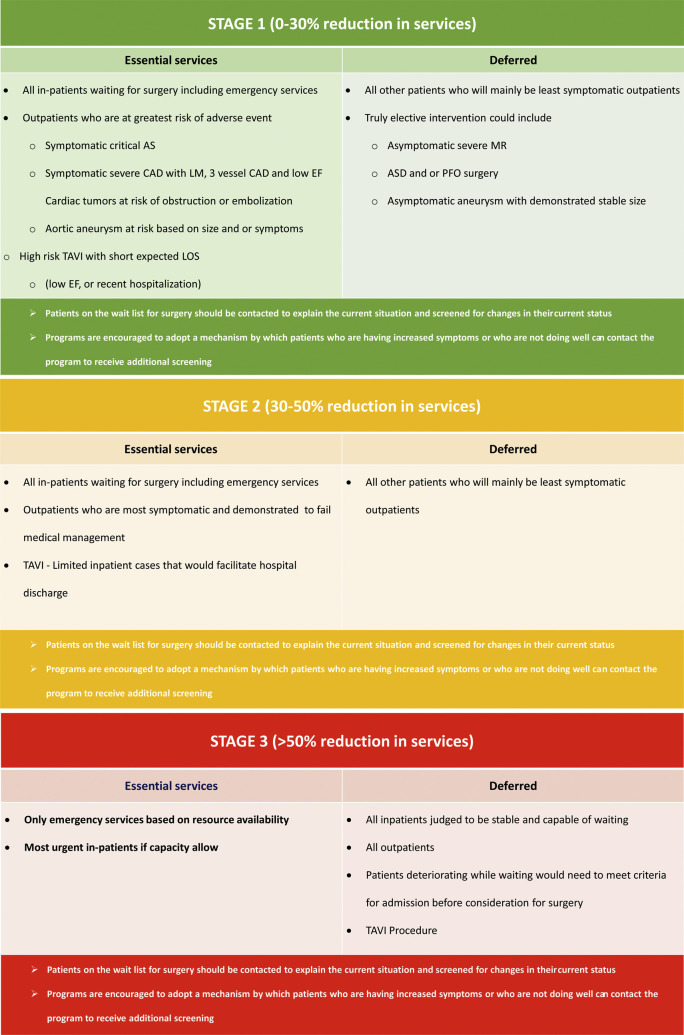

Cardiac surgeons should triage patients that are in hospital or on the elective wait list in a manner that is based not only on the patient’s clinical status and risk-factor profile but also on the extent to which services are available or have been reduced in response to the COVID-19 pandemic (Fig. 2 ). This is a strategy similar to the one recently adopted by the Canadian Association of Interventional Cardiology (CAIC).4 Undoubtedly, there is concern that the proposed prioritization strategy will result in a surgical delay and may put patients at significantly increased risk. As such, it is critically important that cardiac surgeons ensure the presence of a robust wait-times database at their institutions that captures rates of adverse events in these patients while on the wait list so that decisions around the reallocation of resources may be made in a timely fashion.

-

5.

Cardiac surgeons should advocate for a continued role for the heart-team model to solicit the input of clinical cardiology, interventional cardiology, interventional radiology, and critical care in determining the optimal intervention for patients: in particular, those who cases are complex or who are at high risk.

-

6.

In an effort to minimize risk to patients, cardiac surgeons should employ virtual clinics—using either a secure form of teleconferencing or videoconferencing—to assess patients from home who are either new referrals, postoperative follow-ups, or currently on the wait list. Similar technology may be used, if available, to assess inpatients from other institutions to avoid potentially unnecessary hospital-to-hospital transfers.

-

7.

When it is feasible, cardiac surgical programs should make every effort to maintain areas within their institutions for cardiac surgery patients that are completely separate from patients with COVID-19, given the vulnerability of the average cardiac surgery patient (increased biological age and cardiovascular risk factors) were they to become infected with COVID-19.

-

8.

Nonemergent cardiac surgical interventions for patients suffering from acute viral infections (such as—but not limited to—COVID-19) are largely discouraged, based on the belief that this could significantly elevate the risk of postoperative acute respiratory distress syndrome and mortality in that setting.5 In the event that a cardiac surgical procedure is performed on presumed or confirmed COVID-19–positive patients, cardiac surgeons must be closely engaged with their hospital administrations and infection control personnel to ensure the safety of the health care team.

-

9.

Cardiac surgeons should take the necessary steps (eg, donning and doffing PPE), as mandated by their institution and their local health authorities, to ensure their own health and well-being as well as the health and well-being of the members of the health care teams that they work with.

-

10.

Cardiac surgeons and their health care teams must be aware of procedures and techniques that may potentially generate increased quantities of aerosol matter including—but not limited to—double-lumen vs single-lumen endotracheal intubation, reoperative minimally invasive surgery requiring lung dissection, and redo sternotomy vs traditional sternotomy.

-

11.

Cardiac surgeons across Canada are encouraged to share their expertise and novel experiences as they relate to the COVID-19 pandemic in a timely manner to improve overall outcomes. For example, protocols for triaging of patients on the wait list, ECMO use, and the operating-room management of COVID-19–positive patients should be posted online, using readily available Web-based platforms that would allow for cardiac surgeons and their teams to learn from each other in real time.

Figure 1.

Visual abstract of the guiding principles for the cardiac surgery.

Figure 2.

Suggested template for patient triage for cardiac surgery procedures to be modified based on local context, infrastructure, and capacity. AS, aortic stenosis; ASD, atrial septal defect; CAD, coronary artery disease; EF, ejection fraction; LM, left main; LOS, length of stay; MR, mitral regurgitation; PFO, patent foramen ovale; TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve implantation.

These are challenging times, and the CSCS is looking for leadership and equanimity. We, as a community, need to continue to rise to the persistently evolving challenges posed by this historic event. We need to employ all of our skills—clinical, academic, administrative, and otherwise—to ensure optimal care for our patients while offering a safe environment for our health care teams. Understanding fully that these listed guiding statements may change over time, given the fluidity and scope of the current pandemic and appreciating that there are geographic differences in practice patterns and the delivery of health care across Canada, it is our hope that this document will be of assistance to our colleagues as the COVID-19 pandemic continues to unfold.

Funding Sources

The authors have no funding sources relevant to the contents of this paper.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

See page 955 for disclosure information.

References

- 1.WHO Director-General's Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020. World Health Organization. www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 March 11, 2020. Accessed April 1, 2020.

- 2.Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Situation Dashboard. World Health Organization, April 1, 2020. https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/685d0ace521648f8a5beeeee1b9125cd Accessed April 1, 2020.

- 3.Public Health Agency of Canada Government of Canada. Canada.ca, Government of Canada, April 1, 2020. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection.html Accessed April 1, 2020.

- 4.Wood DA, Sathananthan J, Cohen EA. Precautions and procedures for coronary and structural cardiac interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic: guidance from Canadian Association of Interventional Cardiology [e-pub ahead of print]. Can J Cardiol, 10.1016/j.cjca.2020.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Groeneveld G.H., van Paassen J., van Dissel J.T. Influenza season and ARDS after cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:772–773. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1712727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]