Dear Editor,

We report here a case of COVID-19 most likely acquired during a flight from Bangui, Central African Republic to Paris, France.

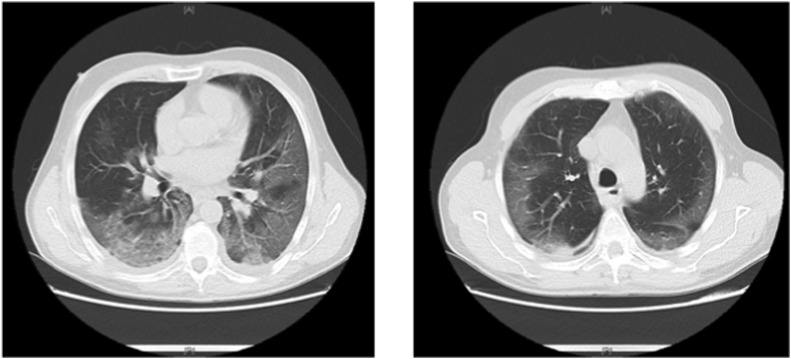

A patient in his fifties without any past medical history consulted his general practitioner, in the Marseille area on March 6th, 2020, because of fever, headache and cough evolving since February 29th. He had been sent by his company (company X) to the Central Africa Republic (CAR) from February 13th to February 25th where he gave presentations (training in management) for 6 days, to a public of about 30 resource directors of several CAR ministries. Because of persistence of fever and cough at day 9-post onset, he was referred to the emergency unit of a local hospital on March 9th. On clinical examination he had fever (40 °C) and dyspnea with oxygen saturation at 91% in ambient air. Pulmonary auscultation revealed bilateral basal crackling sounds. Malaria was ruled-out by blood smear microscopic examination and influenza was ruled-out by PCR on nasal swab fluid. C-reactive protein was at 103 mg/L and white blood cell count was at 8.8 Giga/L. Naso-pharyngeal swab fluid was tested for SARS-CoV-2 by RT-PCR as previously described [1] and resulted positive. The patient was immediately transferred to our center (IHU Méditerranée Infection) for hospitalization in a highly contagious patient section. A Chest CT-scan showed bilateral interstitial pulmonary infiltrates (Fig. 1 ). Progressive aggravation led to his temporary transfer to an intensive care unit for five days, before coming back to our ward where he is still hospitalized at the time of writing. The patient reported that his partner (in her fifties) who works for company X and undertook the same business travel, had cough and fever from February 25th to February 29th that resolved thereafter. She had a negative SARS-Cov-2 RT-PCR on a nasopharyngeal sample obtained on March 3rd.

Fig. 1.

Chest CT-scan showing bilateral pulmonary infiltrates.

In a recently published study, conducted in COVID-19 patients, fewer than 2.5% of infected persons showed symptoms within 2.2 days (CI, 1.8–2.9 days) of exposure, and symptom onset occurred within 11.5 days (CI, 8.2–15.6 days) for 97.5% of infected persons. The estimate of the dispersion parameter was 1.52 (CI, 1.32 to 1.72), and the estimated mean incubation period was 5.5 days [2]. Given the incubation time range of COVID-19, we excluded that our patient acquired COVID-19 in France before leaving to CAR. Furthermore, only 15 documented cases were identified in France before our patient traveled to CAR none of which was documented in Marseille area, where the patient currently lives [3]. Acquisition in France on return, between February 25th and 27th, with a short incubation time was considered possible, but unlikely given that no local circulation was documented in Marseille area during this period of time [3]. The more likely place of exposure was therefore suspected to be in CAR, in a first instance, because the patient had multiple contacts in small closed rooms with several groups of people. However, investigation conducted by telephone in collaboration with the Medical Doctor of the Pasteur Institute of Bangui, where the meeting was organized, and by contacting the three other French collaborators from the company X who participated to the meeting, revealed that none of the other French and African participants presented with respiratory symptoms during the event or soon after. This data provides no strong argument for a potential exposure of our patient during his stay in CAR. Furthermore, the first confirmed case of COVID-19 in CAR was identified on March 8th only, in an Italian patient flying from Milano, Italy to CAR, long after our patient returned to France [4]. In addition, no case of COVID-19 was reported to the GeoSentinel network (https://www.istm.org/geosentinel) in patients returning from CAR, so far. By contrast, the first case of COVID-19 diagnosed in Cameroun was a French national who entered in the country after flying Air France (AF775, on February, 24th) from Paris to Yaoundé with a stopover in Bangui [5]. Our patient and his partner, used the same flight from Bangui to Yaoundé and then to Paris and Marseille in economic class. Therefore, our patient likely get infected in the plane, while traveling with the patient diagnosed eleven days later with COVID-19, in Cameroun. Investigation by Air France medical service is currently ongoing. Of note, of the three other French employees from company X who participated to the meeting, one traveled back on the same flight but in business class and the other two came back in France two days later. Aircraft transmission of COVID-19 has already been reported in China which corroborates our view [6]. This report illustrates how easily SARS-CoV-2 may travel together with their human carriers and spread the virus on board. Travel restrictions clearly make sense in the current context, not only to limit the spread of the disease to still unaffected areas but also to prevent travelers from getting infected on board.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Alain Berlioz-Arthaud from the Pasteur Institute in Bangui for his support kindly helping us in retracing the events. We thank David Hamer and Michael Libman from GeoSentinel for sharing information.

References

- 1.Amrane S., Tissot-Dupont H., Doudier B., Eldin C., Hocquart M., Mailhe M. Rapid viral diagnosis and ambulatory management of suspected COVID-19 cases presenting at the infectious diseases referral hospital in Marseille, France, - January 31st to March 1st, 2020: a respiratory virus snapshot. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020 Mar 20;101632 doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101632. [Online ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lauer S.A., Grantz K.H., Bi Q., Jones F.K., Zheng Q., Meredith H.R. The incubation period of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) from publicly reported confirmed cases: estimation and application. Ann Intern Med. 2020 doi: 10.7326/M20-0504.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.France Santé Publique. COVID-19. Point épidémiologique – situation au 4 mars. 2020 – 16. https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/recherche/#search=COVID-19%20:%20point%20epidemiologique&sort=date (available from : accessed 21/03/20020.

- 4.Luka Radio Ndeke. RCA : un premier cas confirmé de Coronavirus à Bangui. https://www.radiondekeluka.org/actualites/sante/35266-rca-un-premier-cas-confirme-de-coronavirus-en-centrafrique.html (available from :

- 5.Cameroun Actu. Dr Manaouda Malachie : «le patient N°1 ne présentait aucun symptôme de coronavirus à son entrée au Cameroun le 24 février». https://actucameroun.com/2020/03/16/dr-manaouda-malachie-le-patient-n1-ne-presentait-aucun-symptome-de-coronavirus-a-son-entree-au-cameroun-le-24-fevrier/ (available from: accessed 21/03/2020)

- 6.Qian GQ, Yang NB, Ding F, Ma AHY, Wang ZY, Shen YF, et al. Epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of 91 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Zhejiang, China: a retrospective, multi-centre case series. QJM. 2020 Mar 17. pii: hcaa089. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcaa089. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]