1. Background

As the COVID-19 pandemic grows, the need for rapid, innovative, and cost-effective emergency response mechanisms and the presence of gaps in critical care capacity become glaringly obvious in most countries and territories worldwide. In the United States, models project that major academic centres' hospitalization capacity will be saturated within weeks, notably including their intensive care unit (ICU) capacity [1]. Furthermore, low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) are at-risk for an inability to manage an anticipated surge of critically ill COVID-19 patients, with current estimates suggesting the availability of 0.1 to 2.5 ICU beds per 100,000 population [2]. While several studies have evaluated critical care capacity in some regions, there has yet to be a comprehensive survey of ICU beds worldwide.

2. Objective

The objective of this study consists of mapping the global availability of critical care infrastructure with a focus on the distribution of ICU beds.

3. Methods and findings

A literature search was performed using the PubMed/MEDLINE and Google Scholar databases to identify the most recent number of ICU beds per country or territory, including pediatric and neonatal ICU but excluding psychiatric ICUs. Additionally, national and international media and grey literature were searched in English and all official languages of each country. Countries were categorized as LMIC versus high-income countries (HICs) according to the World Bank income group classification [3]. For low-income countries, it was assumed that ICU beds were only available in teaching and referral hospitals.

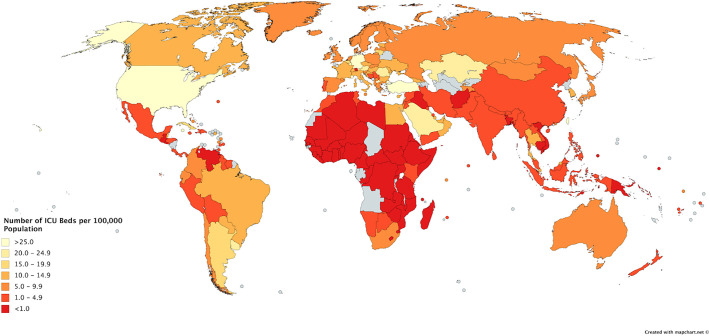

Data was available for 182 countries and territories, ranging from 0 to 59.5 ICU beds per 100,000 population (Fig. 1 ; Appendix Table 1). Globally, at least 96 countries and territories had a density of less than 5.0 ICU beds per 100,000 population. The availability of ICU beds ranged from none (Nauru, Solomon Islands, and South Sudan) to 21.3 per 100,000 population (Kazakhstan) in LMICs and none (Liechtenstein and Palau) to 59.5 per 100,000 population (Monaco) in HICs. In Africa, densities ranged from 0 (South Sudan) to 10.6 (Egypt) per 100,000 population. Apart from Seychelles (6.3), South Africa (8.9), and Egypt (10.6), all African countries had a density of less than 5.0 ICU beds per 100,000 population.

Fig. 1.

Global availability of intensive care unit (ICU) beds per 100,000 population. Created with mapchart.net.

4. Discussion

Traditionally, ICU beds have a high baseline occupancy rate. 5% of COVID-19 cases are expected to require ICU admission, mathematically already overwhelming a handful of countries based on real-time case numbers, and disregarding the need for ICU beds for non-COVID-19 emergencies [4]. To respond to the growing shortages of ICU beds and ventilators, frameworks for rationing have been developed to ensure the fair allocation of scarce resources [5].

As the world responds to the growing COVID-19 pandemic, a shift in contemporary global public health priorities exposes critical gaps in health systems around the world. Whilst the critical care capacity in LMICs was insufficient prior to the pandemic, deficiencies grow to include highly-resourced health systems around the world.

Our study has several limitations. First, the scarcity of comprehensive data available in peer-reviewed literature or white papers required the reliance on local and national media to collect data on the number of ICU beds for 52 countries and territories. Our results are limited to internet-searchable information, and we cannot disregard the possibility of the numbers to be under-estimates because of publicly under-reporting. Second, accessibility to ICU care, a challenge in many countries with (partially) private health care systems, is not taken into account when assessing capacity. The availability of an ICU bed does not automatically translate to sufficient resources to sustain a critically ill patient. Finally, many countries are rapidly converting regular hospital wards, operating theatres, and non-clinical spaces to make-shift ICUs to manage the growing number of critically ill patients. Despite these limitations, we believe that our analysis provides an initial, comprehensive view of the global availability of baseline critical care capacity. Our findings highlight the need for ministries of health to track and share their critical care inventory, to allow for a clearer assessment of needs and opening the door to more unified efforts in fighting the pandemic.

Funding source

None.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2020.04.012.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

ICU bed capacity by country or territory

References

- 1.Weissman G.E., Crane-Droesch A., Chivers C. Locally informed simulation to predict hospital capacity needs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Intern Med. 2020 doi: 10.7326/M20-1260. Epub ahead of print 7 April 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turner H.C., Hao N.V., Yacoub S. Achieving affordable critical care in low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4(3) doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001675. e001675. Published 2019 Jun 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The World Bank World Bank Country and Lending Groups. Published 2020. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups Accessed March 30, 2020.

- 4.Dong E., Du H., Gardner L. An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time [published online ahead of print, 2020 Feb 19] Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30120-1. S1473–3099(20)30120–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.White D.B., Lo B. A framework for rationing ventilators and critical care beds during the COVID-19 pandemic [published online ahead of print, 2020 Mar 27] JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

ICU bed capacity by country or territory