Dear Editor,

The city of Wuhan in China - toward the end of 2019 - experienced emergence of a new coronavirus disease (COVID-19), formally named severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) [1]. Unlike other animal-to-human coronavirus diseases, this virus shows potential to spread more rapidly in certain areas or countries within the short period of a few weeks. A low incidence of novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has been reported from countries with a high incidence of malarial infections. The author investigates whether the rapid spread of COVID-19 is related to the incidence of malaria cases in countries affected by COVID-19. The study utilized publicly available data on COVID-19 cases by countries reporting [2]. For each country affected by COVID-19, the incidence of malaria cases per 1000 population at risk in 2015 has been retrieved [3].

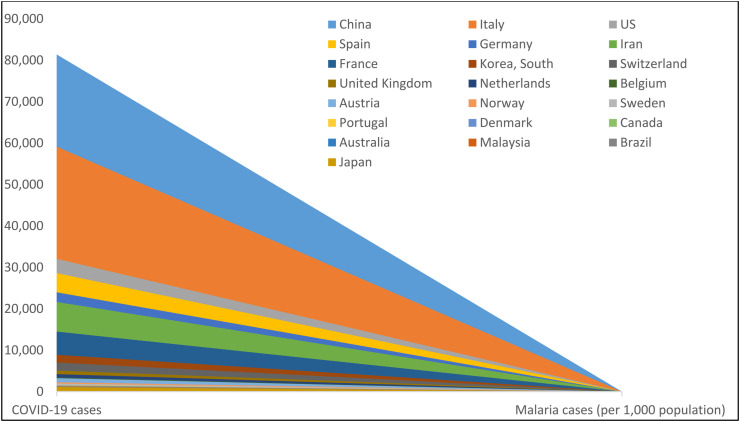

As of March 22, 2020, results indicate world regions that are malaria free or recorded limited malarial infections reported a large number of COVID-19 cases (Fig. 1 ). For instance, in China (81,397 COVID-19 cases), Italy (59,138 COVID-19 cases), US (32,057 COVID-19 cases), Spain (28,603 COVID-19 cases), and Germany (23,974 COVID-19 cases). China reported limited transmission of malaria in 2015 (<0.01 per 1000 population at risk). No malaria cases were reported in Italy, US, Spain, and Germany in 2015.

Fig. 1.

As of March 22, 2020, incidence of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and malarial infections. Countries that are malaria-free or that have limited affect reported high cases of COVID-19.

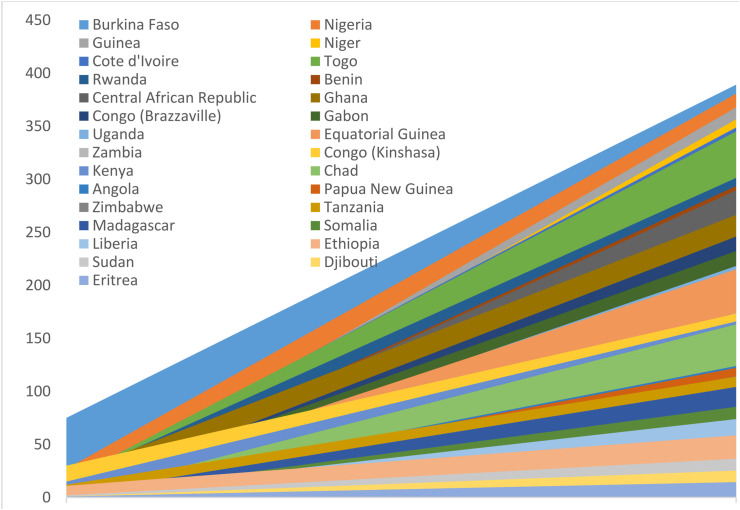

On the other hand, world regions affected by malaria reported fewer or no cases of COVID-19 (Fig. 2 ). The countries most affected by malaria were Burkina Faso (389.2 per 1000 population at risk), Nigeria (380.8 per 1000 population at risk), Guinea (367.8 per 1000 population at risk), and Niger (356.5 per 1000 population at risk). Burkina Faso reported 75 cases of COVID-19 and Nigeria reported 27 cases of COVID-19. Guinea and Niger each reported only 2 cases of COVID-19. One possible explanation of the limited spread of COVID-19 on countries affected by malaria is the wide use of anti-malarial drugs. This is in line with a study published in 2005 reporting that chloroquine tends to be an effective antiviral agent pre- and post-infection of SARS-CoV-1 [4].

Fig. 2.

As of March 22, 2020, incidence of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and malarial infections. Countries affected by malaria reported low cases of COVID-19.

It is possible that different viral strains of COVID-19 are currently circulating in Africa as the infection and death rates vary greatly by country. Despite the strong trade and travel flows links between China and African countries, limited community outbreaks of COVID-19 have been reported in certain countries in Africa. It is also possible that limited international travels to other affected continents and environmental factors may explain the limited spread of COVID-19 in Africa.

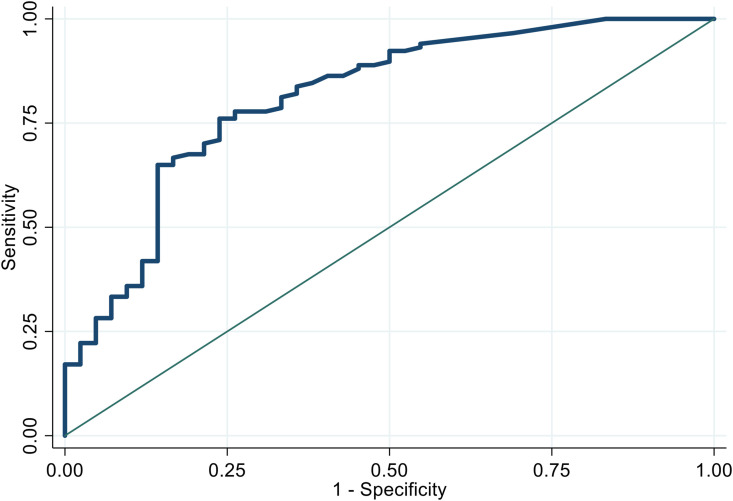

The Poisson regression is used to assess whether the malarial incidence rate (per 1000 population at risk) is a predictor for increased cases of COVID-19. The model shows that as the malarial incidence rate (per 1000 population at risk) increased by 1, the COVID-19 incidence rate tends to decrease by 8.82%. A ROC curve analysis (Fig. 3 ) indicated that the incidence of COVID-19 was a good classifier (AUC = 0.8115) for countries that were malaria free or recorded limited malarial infections (5 or less per 1000 population at risk).

Fig. 3.

The incidence of COVID-19 as a predictor for malaria-free or limited malaria infections.

As of March 22, 2020, malarial drugs have not yet been approved by the FDA as treatments for COVID-19. However, the use of malarial drugs such as chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine shown great promise in treating COVID-19, specifically in China [5] and in France [6], as well as in a number of ongoing clinical trials across the world. Another study in France investigated the effectiveness of both hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin with COVID-19, 97.5% of 80 patients improved clinically at Day 5, except two elderly patients (2.5%) [7].

In conclusion, the spread and clinical management of the current coronavirus outbreaks may require guidelines that incorporate the use of anti-malarial drugs. Future studies are needed to investigate whether a) the use of anti-malarial drugs, b) the environmental factors, and c) different strains of COVID-19 reduce the incidence of COVID-19 infection in countries affected by malaria.

Funding source

None.

Ethics approval

The study may not require IRB/ethics committee approval due to utilization of publicly reported data.

Disclaimer

The contents, views or opinions expressed in this publication or presentation are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect official policy or position of Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, the Henry M Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, the Department of Defense (DoD), or Departments of the Army, Navy, or Air Force. Mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Declaration of competing interest

The author has no conflict of interest to disclosure.

References

- 1.Letko M., Marzi A., Munster V. Functional assessment of cell entry and receptor usage for SARS-CoV-2 and other lineage B betacoronaviruses. Nat Microbiol. 2020 Feb 24:1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0688-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dong E., Du H., Gardner L. An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 Feb 19 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30120-1. S1473-3099(20)30120-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roser Max, Ritchie Hannah. Malaria. 2020. https://ourworldindata.org/malaria Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from:

- 4.Vincent M.J., Bergeron E., Benjannet S., Erickson B.R., Rollin P.E., Ksiazek T.G., Seidah N.G., Nichol S.T. Chloroquine is a potent inhibitor of SARS coronavirus infection and spread. Virol J. 2005 Dec 1;2(1):69. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-2-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu J., Cao R., Xu M., Wang X., Zhang H., Hu H., Li Y., Hu Z., Zhong W., Wang M. Hydroxychloroquine, a less toxic derivative of chloroquine, is effective in inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro. Cell Discov. 2020 Mar 18;6(1):1–4. doi: 10.1038/s41421-020-0156-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colson P., Rolain J.M., Lagier J.C., Brouqui P., Raoult D. Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine as available weapons to fight COVID-19. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020 Mar 4:105932. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gautret P., Lagier J.C., Parola P., Meddeb L., Sevestre J., Mailhe M., Doudier B., Aubry C., Amrane S., Seng P., Hocquart M. Clinical and microbiological effect of a combination of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin in 80 COVID-19 patients with at least a six-day follow up: a pilot observational study. Trav Med Infect Dis. 2020 Apr 11:101663. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]