The ongoing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is a substantial challenge for health-care systems and their infrastructure. RT-PCR-based diagnostic confirmation of infected individuals is crucial to contain viral spread because infection can be asymptomatic despite high viral loads. Sufficient molecular diagnostic capacity is important for public health interventions such as case detection and isolation, including for health-care professionals.1

Protocols for RNA RT-PCR testing of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) became available early in the pandemic, yet the infrastructure of testing laboratories is stretched and in some areas it is overwhelmed.2 We propose a testing strategy that is easy to implement and can expand the capacity of the available laboratory infrastructure and test kits when large numbers of asymptomatic people need to be screened. We introduced the pooling of samples before RT-PCR amplification, and only in the case of positive pool test results is work-up of individual samples initiated, thus potentially substantially reducing the number of tests needed.

Viral load during symptomatic infection with SARS-CoV-2 was investigated by Zou and colleagues.3 To analyse the effect of pooling samples on the sensitivity of RT-PCR, we compared cycle threshold (Ct) values of pools that tested positive with Ct values of individual samples that tested positive.

We isolated RNA from eSwabs (Copan Italia, Brescia, Italy) using the NucliSens easy MAG Instrument (bioMeriéux Deutschland, Nürtingen, Germany) following the manufacturers' instructions. PCR amplification used the RealStar SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR Kit 1.0 RUO (Altona Diagnostics, Hamburg, Germany) on a Light Cycler 480 II Real-Time PCR Instrument (Roche Diagnostics Deutschland, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturers' instructions.

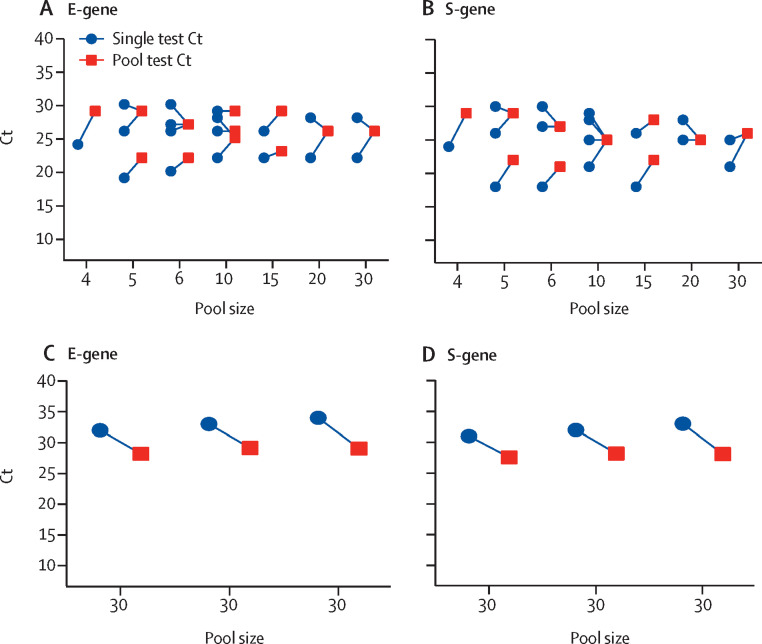

Our results show that over a range of pool sizes, from four to 30 samples per pool, Ct values of positive pools were between 22 and 29 for the envelope protein gene (E-gene) assay and between 21 and 29 for the spike protein gene (S-gene) assay. Ct values were lower in retested positive individual samples (figure A, B ). The Ct values for both E-gene and S-gene assays in pools and individual positive samples were below 30 and easily categorised as positive. Ct value differences between pooled tests and individual positive samples (Ctpool– Ctpositive sample) were in the range of up to five. Even if Ct values of single samples were up to 34, positive pools could still be confidently identified (figure C, D). Sub-pools can further optimise resource use when infection prevalence is low. Generating a pool of 30 samples from three sub-pools of ten samples can reduce retestings. If the large pool is positive, the three sub-pools are reanalysed, and then the individual samples of the positive sub-pool. In our analyses during March 13–21, 2020, testing of 1191 samples required only 267 tests to detect 23 positive individuals (prevalence 1·93%). The rate of positive tests was 4·24% in our institution during this period.

Figure.

Ct values of single versus pooled samples

Absolute Ct values of positive pools (13 of 164 tested pools) in relation to pool size and corresponding Ct values of individual positive samples for the E-gene assay (A) and the S-gene assay (B). Absolute Ct values were below 30 for all pool sizes. Three positive individual samples with Ct values greater than 30 were spiked into negative pools of 30 samples and tested with E-gene (C) and S-gene (D) assays. We hypothesise that the lower Ct values of pools than of single samples were because of the carrier effect of the higher RNA content in pools. Connecting lines show positive single samples and their corresponding pools. Ct=cycle threshold. E-gene=envelope protein gene. S-gene=spike protein gene.

These data suggest that pooling of up to 30 samples per pool can increase test capacity with existing equipment and test kits and detects positive samples with sufficient diagnostic accuracy. We must mention that borderline positive single samples might escape detection in large pools. We see these samples typically in convalescent patients 14–21 days after symptomatic infection. The pool size can accommodate different infection scenarios and be optimised according to infrastructure constraints.

Acknowledgments

We declare no competing interests. Intramural funding was obtained from Saarland University Medical Center.

References

- 1.Koo JR, Cook AR, Park M, et al. Interventions to mitigate early spread of SARS-CoV-2 in Singapore: a modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30162-6. published online March 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corman VM, Landt O, Kaiser M, et al. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT-PCR. Euro Surveill. 2020;25 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.3.2000045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zou L, Ruan F, Huang M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 viral load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1177–1179. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]