Abstract

Medical science and patient care have historically focused on male patients. Many diagnoses in women are still undetermined and it takes several years longer to establish comparable diagnoses in women as in men. Women live longer and have more unhealthy years with ageing than men. Sociocultural aspects vary importantly between the genders and have a different impact on health, wellbeing and many diseases. We still have a long way to go to achieve gender equality and equal rights for women worldwide. Female values, such as creativity, empathy, mutual connection and emotional skills, are eminent in healthcare. Efforts to establish more highly respected and leading positions for women working in the health sector will be a great incentive to put women’s health higher on the agenda.

Keywords: Women, Healthcare, Medical science, Patient care

1. Gender inequality in healthcare

The United Nations has estimated that worldwide 985 million women in 2020 will be aged 50 and over. In 2050 the figure will rise to 1.65 billion. In 2020 the total female population is 3.8 billion and the estimate for 2050 is 4.8 billion [1]. Women’s health issues are often limited to sexual and reproductive issues, whereas sex- and gender differences are relevant to many medical disciplines and all aspects of wellbeing and healthcare [2,3]. The time needed to assess comparable medical diagnoses has been found to be several years earlier in men compared to women. This is in line with the fact that within many European countries the number of unhealthy years with ageing starts earlier in women than in men [4]. As women in general live longer, this importantly affects their quality of life and this poses an enormous medical and economic pressure on society. Frequently used undetermined diagnoses such as fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome and psychosocial distress are typically more often present in women. In addition, as it often happens in clinical practice when there is no clear explanation for certain symptoms in women over 50 years, menopause is frequently used as an overruling container diagnosis. However, we should realize that these container diagnoses are more representative of a lack of knowledge in the medical field rather than of an overkill of unclear symptoms in women. Barriers to regular healthcare, often for economic reasons, are also present in women during their reproductive years, when a solid basis for prevention needs to be set [5].

2. Women and cardiovascular disease

Over the past decades non-communicable diseases and risk factors like hypertension have become the main causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide, even more in women than in men [6]. Women and men are physiologically importantly different, which is adversely impacted by health disparities related to sociocultural factors. For many women, gender discrimination systematically undermines access to health care, for reasons that include fewer financial resources and constraints on mobility [7]. In addition, poverty, low education level, sexual and domestic violence have a huge impact on cardiovascular diseases (CVD) and the traditional risk factors [8]. It has been shown that in countries with a low socio-demographic index (SDI < 0.25), the highest CVD mortality rates shift from men to women [9]. However, even high-income countries continue to face substantial CVD mortality and have reached a plateau in the decline of death from ischemic heart disease over recent years, especially in women. Women with CVD are still considered along the male standard worldwide, leading to misdiagnoses, undertreatment and a lower quality of life (QOL) [10,11].

3. Women, gender equality and health

The year 2020 is critical for women’s health in the perspective of gender equality and equity. Twenty-five years after the Beijing Declaration and Platform for action gender equality is still importantly neglected in public health and many areas of healthcare. This year also marks the 5th anniversary of the sustainable development goals (SDGs) of which SDG 3 (health) and SDG 5 (gender equality) are the cornerstone to improve women’s health [12]. However, over the last few years serious concerns have arisen on the current global gender-backlash, which is controlled by various powerful conservative, populist and religiously dominated governments. Anti-gender campaigners have even gone so far as trying to overturn existing laws on basic human rights.

In a special edition on women’s health in 2019 the Lancet has underscored that gender norms are important in creating pathways for better health outcomes and they may be the key to realize the sustainable development challenge of health for all [[13], [14], [15], [16], [17]]. Gender norms are the spoken and unspoken rules of societies in accepted behaviors of girls and boys, women and men—how they should act, look, and even think or feel. Gender norms are challenged in families, communities, schools, workplaces, institutions, and the media. These sociocultural expectations start early in life and powerfully shape individuals’ attitudes, opportunities, experiences, and behaviors, with important health consequences throughout the life course [17].

4. Empower women working in healthcare

The Lancet women’s commission underscores the need to take actions, also in the health sector itself. Health institutions reinforce gender inequalities both in health-care delivery and in the division of labor in the health workforce. Women are disproportionately socially conditioned into so-called care roles, such as nurse, midwife, and frontline community health worker. The recent global COVID-19 crisis has shown again how important these hard-working women are in patient care. Men are disproportionately represented into so-called cure roles, such as physician and specialist, whereas women are under-represented in jobs with increased pay and leadership positions. Although the majority of the health workforce is female, most women hold positions with little power to change systems, organizations, or their careers, which may lead to work stress, job dissatisfaction, and burnout [16]. With more than 50% female medical students in most countries, they are less likely than men to work in higher paying specialties or to be offered the same opportunities for professional advancement and careers at senior level [18,19]. Among female trainees in cardiology sexist language and behavior is common and often an argument to decide for another sub-speciality [20]. Gender discrimination has a cost in health outcomes because a greater proportion of female physicians in the workforce has been linked to reduced maternal and infant mortality and better treatment of cardiac patients [21] Despite this evidence, analysis of the effect of gender norms on health systems remains neglected. This has been confirmed in a WHO report in March 2019 which emphasizes that women account for the majority (75%) of health and social care workers, but only 25% hold senior roles [22].

5. Female values in Healthcare

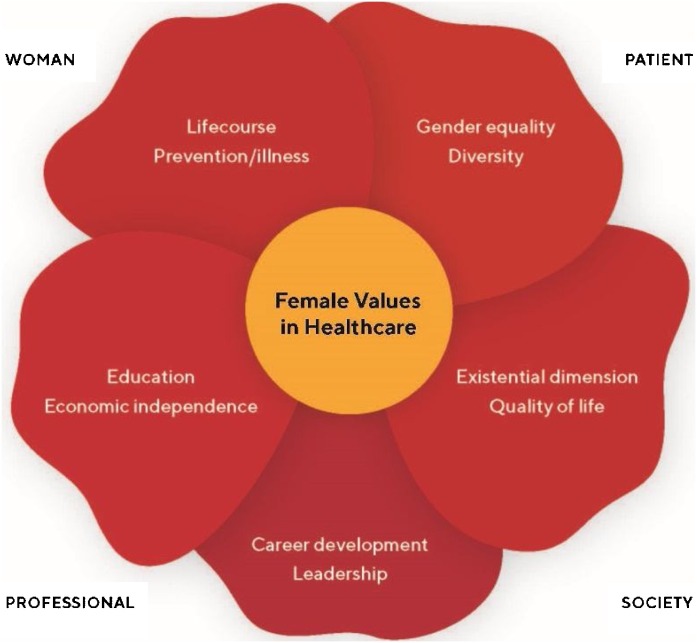

Today’s societal values are predominantly based on masculine ideals or characteristics. Every type of organization, whether it is healthcare, governmental or commercial business is based on a masculine value system. Whereas men are considered to be more assertive, focused, competitive, action-oriented, ambitious and driven to achieve material success, women are more creative, empathetic, nurturing and compassionate with a high concern for justice. Women are not only focused on results, but also on the process itself and mutual connection. These female values are critical in all aspects of healthcare from both the perspectives of women as patients and as health care professionals (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Female values in healthcare are important to women from the perspective of the patient and the healthcare professional.

6. Conclusion

Over the past decades progress in women’s health has been hampered world-wide by a large number of socio-cultural and political reasons. The current international gender-backlash is a serious threat to the fundaments of women’s rights. By improving leading positions of women in healthcare and supporting their unique values, all theme’s connected with women’s health will be put higher on the agenda and this will speed-up the realization of SDGs 3 and 5 in 2030.

Ethical statement

This paper has been written according to all scientific standards

Contributors

Angela H.E.M. Maas is the sole author.

Funding

No external funding was received for the preparation of this article.

Provenance and peer review

This article was commissioned and has undergone peer review.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The author declares that she has no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.https://population.un.org/wpp/.

- 2.Westergaard D., Moseley P., Sorup F.K.H., Baldi P., Brunak S. Population-wide analysis of differences in disease progression patterns in men and women. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):666. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-08475-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartz D., Chitnis T., Kaiser U.B., et al. Clinical advances in sex- and gender-informed medicine to improve the health of all: a review. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.7194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database.

- 5.Ranji U., Salganicoff A. Rousseau D, for the Kaiser Family Foundation. Barriers to Care Experienced by Women in the United States. JAMA. 2019;321(22):2154. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.5271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collaborators GBDCoD Global, regional, and national age-sex specific mortality for 264 causes of death, 1980-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390(10100):1151–1210. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32152-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.http://www.unwomen.org/en/news/in-focus/women-and-the-sdgs/sdg-3-good-health-well-being.

- 8.https://eige.europa.eu/publications/gender-health.

- 9.Roth G.A., Johnson C., Abajobir A., et al. Global, regional, and national burden of cardiovascular diseases for 10 causes, 1990 to 2015. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(1):1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.04.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maas A.H., van der Schouw Y.T., Regitz-Zagrosek V., et al. Red alert for Women’s Heart: the urgent need for more research and knowledge on cardiovascular disease in women. Eur Heart J. 2011;32(11):1362–1368. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wenger N.K. Women and coronary heart disease: a century after Herrick: understudied, underdiagnosed, and undertreated. Circulation. 2012;126(5):604–611. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.086892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lancet The. 2020: a critical year for women, ender equity, and health. Lancet. 2020;395(10217):1. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)33170-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heise L., Greene M.E., Opper N., et al. Gender inequality and restrictive gender norms: framing the challenges to health. Lancet. 2019;393(10189):2440–2454. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30652-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weber A., Cislaghi B., Meausoone V., et al. Gender norms and health: insights from global survey data. Lancet. 2019;393(10189):2455–2468. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30765-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heymann J., Levy J.K., Bose B., et al. Improving health with programmatic, legal, and policy approaches to reduce gender inequality and change restrictive gender norms. Lancet. 2019;393(10190):2522–2534. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30656-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hay K., McDougal L., Percival V., et al. Disrupting gender norms in health systems: making the case for change. Lancet. 2019;393(10190):2535–2549. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30648-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta G.R., Oomman N., Grown C., et al. Gender equality and gender norms: framing the opportunities for health. Lancet. 2019;393(10190):2550–2562. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30651-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shannon G., Minckas N., Tan D., et al. Feminisation of the health workforce and wage conditions of health professions: an exploratory analysis. Hum Resour Health. 2019;17(1):72. doi: 10.1186/s12960-019-0406-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frank E., Zhao Z., Sen S., Guille C. Gender Disparities in Work and Parental Status Among Early Career Physicians. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(8) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.8340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sinclair H.C., Joshi A., Allen C., et al. Women in Cardiology: The British Junior Cardiologists’ Association identifies challenges. Eur Heart J. 2019;40(3):227–231. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baumhäkel M., Müller U., Böhm M. Influence of gender of physicians and patients on guideline-recommended treatment of chronic heart failure in a cross-sectional study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2009;11(3):299–303. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfn041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.https://www.who.int/hrh/resources/en_exec-summ_delivered-by-women-led-by-men.pdf?ua=1.