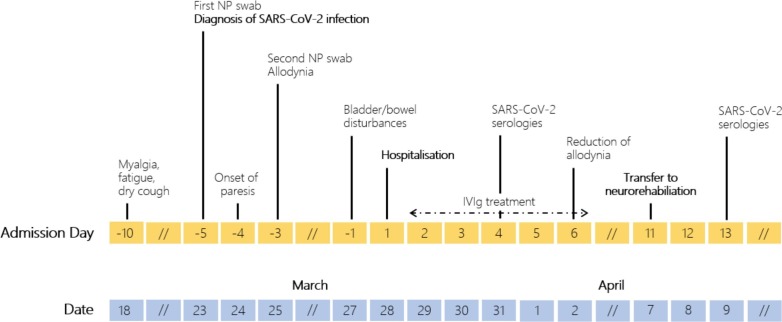

A man in his seventies was hospitalized because of paraparesis, distal allodynia, difficulties in voiding and constipation. Ten days before he developed myalgia, fatigue, and a dry cough. He was diagnosed with an oligosymptomatic coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [positive severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) RT-PCR in two nasopharyngeal (NP) swab]. At day 25 from RT-PCR, serum anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgA and IgG ELISA (Euroimmun, Seekamp, Germany) resulted positive. Figure shows a timeline of the main events (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Timeline indicating the main events of the patient’s illness. Top row: clinical events (before/after patient’s hospitalisation); bottom row: corresponding dates. NP = nasopharyngeal.

The patient had no medical history. Vital signs were normal. Physical examination revealed fine crackles in the left base, bilateral lower limb flaccid paresis, absent deep tendon reflexes of the upper and lower limb and idiomuscular response to percussion of the muscle tibialis anterior, indifferent plantar reflexes. There was no sensory deficit. Blood tests were normal. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis showed albuminocytologic dissociation without intrathecal IgG synthesis. FilmArray Meningitis/Encephalitis (ME) Panel testing (BioFire Diagnostics, Salt Lake City, UT) and SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR were negative; antiganglioside antibodies were not detected. Chest X-ray was normal. Contrast-enhanced MRI excluded myelopathy. Nerve conduction study showed sensorimotor demyelinating polyneuropathy with “sural sparing pattern”; F wave study showed decreased persistence or absent F-waves in tested nerves.

Findings were compatible with an acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy, the most common subtype of Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS). On the day following admission the patient was started on intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIg; IgPro10, Privigen®; 0.4 g/kg/day for 5 days). Improvement was rapid. At day eleven from hospitalisation the patient was transferred to the Division of Neurorehabilitation.

SARS-CoV-2 is a novel coronavirus first detected in Wuhan, Hubei province, China, in late 2019 and the etiologic agent of COVID-19 (Zhu et al., 2020). It belongs to the genus β-coronavirus, like HCoV-OC43 and HCoV-HKU1 (responsible of mild upper respiratory tract infections), and MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV [the agents of the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) and of the SARS, respectively] (Fehr and Perlman, 2015). GBS is an acute, immune-mediated, typically postinfectious polyneuropathy. Its main manifestations are progressive bilateral weakness of arms and legs and hyporeflexia/areflexia in the affected limbs. Dysautonomia (including bowel and bladder dysfunction) is common (Leonhard et al., 2019).

Our patient had a classic presentation of GBS. He tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 before the first signs of polyneuropathy, thus supporting a postinfectious GBD phenotype.

Before the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, only two cases of coronavirus-associated GBS were reported in the literature: a man with MERS-CoV who developed Bickerstaff brainstem encephalitis (a variant of GBS) (Kim et al., 2017), and a boy who developed an atypical GBS after a respiratory infections sustained by HCoV-OC43 (Sharma et al., 2019). Up to now, two paper have described a possible association between SARS-CoV-2 and GBS (Zhao et al., 2020, Toscano et al., 2020).

We describe one of the first cases of GBS occurring in the context of SARS-CoV-2 infection. In the context of the current pandemic, clinicians should be aware that GBS can complicate SARS-CoV-2 infection an affect patient’s outcomes, thus requiring a prompt intervention. Moreover, physician should remember that that the incidence of GBS during outbreaks of infectious disease can increase (as with the recent Zika virus epidemic) (Leung, 2020). To note, although neurological manifestation in COVID-19 are frequently described (like in the recent case report by Ye et al. (2020), the neuroinvasive potential of SARS-CoV-2 remains hitherto inexplored (Wu et al., 2020).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.074.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Fehr A.R., Perlman S. Coronaviruses: an overview of their replication and pathogenesis. Methods Mol. Biol. 2015;1282:1–23. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2438-7_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.E., Heo J.H., Kim H.O. Neurological complications during treatment of middle east respiratory syndrome. J. Clin. Neurol. 2017;13:227–233. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2017.13.3.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonhard S.E., Mandarakas M.R., Gondim F.A.A. Diagnosis and management of Guillain Barré syndrome in ten steps. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2019;15:671–683. doi: 10.1038/s41582-019-0250-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung C. A lesson learnt from the emergence of Zika virus: what flaviviruses can trigger Guillain-Barré syndrome? J. Med. Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25717. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma K., Tengsupakul S., Sanchez O., Phaltas R., Maertens P. Guillain-Barré syndrome with unilateral peripheral facial and bulbar palsy in a child: a case report. SAGE Open Med. Case Rep. 2019 doi: 10.1177/2050313X19838750. 2050313X19838750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toscano G., Palmerini F., Ravaglia S. Guillain-Barré syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009191. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y., Xu X., Chen Z. Nervous system involvement after infection with COVID-19 and other coronaviruses. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.03.031. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye M., Ren Y., Lv T. Encephalitis as a clinical manifestation of COVID-19. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.017. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H., Shen D., Zhou H., Liu J., Chen S. Guillain-Barré syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection: causality or coincidence? Lancet Neurol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30109-5. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.