Abstract

A novel coronavirus appeared in Wuhan, China has led to major outbreaks. Recently, rapid classification of virus species, analysis of genome and screening for effective drugs are the most important tasks. In the present study, through literature review, sequence alignment, ORF identification, motif recognition, secondary and tertiary structure prediction, the whole genome of SARS-CoV-2 were comprehensively analyzed. To find effective drugs, the parameters of binding sites were calculated by SeeSAR. In addition, potential miRNAs were predicted according to RNA base-pairing. After prediction by using NCBI, WebMGA and GeneMark and comparison, a total of 8 credible ORFs were detected. Even the whole genome have great difference with other CoVs, each ORF has high homology with SARS-CoVs (>90%). Furthermore, domain composition in each ORFs was also similar to SARS. In the DrugBank database, only 7 potential drugs were screened based on the sequence search module. Further predicted binding sites between drug and ORFs revealed that 2-(N-Morpholino)-ethanesulfonic acid could bind 1# ORF in 4 different regions ideally. Meanwhile, both benzyl (2-oxopropyl) carbamate and 4-(dimehylamina) benzoic acid have bene demonstrated to inhibit SARS-CoV infection effectively. Interestingly, 2 miRNAs (miR-1307-3p and miR-3613-5p) were predicted to prevent virus replication via targeting 3′-UTR of the genome or as biomarkers. In conclusion, the novel coronavirus may have consanguinity with SARS. Drugs used to treat SARS may also be effective against the novel virus. In addition, altering miRNA expression may become a potential therapeutic schedule.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, Drug screening, Epitope, Genomic, Homology, miRNA, ORF

Introduction

The recent emergence of a novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2), discovered from the Huanan seafood market and caused an outbreak of unusual viral pneumonia in Wuhan, a central city of China. As of March 13th, 2020, a total of 81003 cases have been confirmed in China. CoVs are common pathogens with highly infectious for humans and vertebrates. They can infect the respiratory, gastrointestinal, hepatic and central nervous system of human, mouse, bat, avian, livestock and many other wild animals.1, 2, 3 Since the outbreaks of the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in 2002 and the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) in 2012, the possibility of CoVs transmission from animal to human has been proved.4,5 Notably, via deep sequencing and etiological investigations, SARS-CoV-2 has been identified as a novel coronavirus similar to SARS-CoV.

CoVs belong to the subfamily Coronavirinae in the family of Coronaviridae of the order Nidovirales. The genome of CoVs is a single-stranded positive-sense RNA (+ssRNA) (~30 kb) with 5′-cap structure and 3′-poly-A tail.6 The genomic RNA is used as a template to directly translate polyprotein (pp) 1a/1 ab, the non-structural proteins (nsps) to form a replication-transcription complex (RTC) in double-membrane vesicles (DMVs).7 Subsequently, a set of subgenomic RNAs (sgRNAs) are synthesized by RTC in a discontinuous transcription manner.8 Genomes and subgenomes of CoVs contain at least 6 open reading frames (ORFs). The first ORF (ORF1a/b), about 2/3 of genome length, encodes 16 non-structural proteins (nsp1-16). These polypeptides will be processed into 16 nsps by virally encoded protease.9,10 Hydrophobic transmembrane domains are present in nsp3, nsp4, and nsp6 in order to anchor the nascent pp1a/pp1ab polyproteins to membranes once RTC formation. Other ORFs on the 1/3 genome near 3′ terminus encodes at least 4 main structural proteins: spike (S), membrane (M), envelope (E), and nucleocapsid (N) proteins. Besides these 4 main structural proteins, different CoVs encode special structural and accessory proteins, such as 3a/b protein. All the structural and accessory proteins are translated from the sgRNAs RNAs of CoVs.8 In addition, a 5′ untranslated region (UTR) and 3′-UTR were also identified in the SARS-CoV-2 genome. Thus, studies about microRNA might be necessary and significant. Furthermore, a number of cellular proteins have been shown to interact with CoVs RNA. These include heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1, polypyrimidine tract binding protein, poly (A)-binding protein, and mitochondrial aconitase.11 Understanding of the genome-structure-function correlation in SARS-CoV-2 is important for the identification of potential anti-viral inhibitors and vaccine targets.

Recent rapid progress in sequencing technologies and associated bioinformatics methodologies has enabled a more in-depth view of the structure and functioning of viral communities, supporting the characterization of emerging viruses.12 Bioinformatics analysis of viruses involves the general tasks related to any novel sequences analysis, including the identification of ORFs, gene functional prediction, homology searching, sequence alignment, and motif and epitope recognition. The predictions of features such as transmembrane domains and protein secondary and tertiary structure are important for analyzing the structure-function relationship of viral proteins encoding. Biochemical pathway analysis can help elucidate information at the biological systems level. Virus-related bioinformatics databases include those concerned with viral sequences, taxonomy, homologous protein families, structures, or dedicated to specific viruses such as influenza. These computational programs provide a resource for genomics and proteomics studies in virology research and are useful for understanding viral diseases, as well as for the design and development of anti-viral agents.

Methods and materials

RNA sequencing and data calibration

The sequence of SARS-CoV-2s was obtained from NCBI, which was provided by Dr. Zhang, a professor from Fudan University. Thus, the process of sequencing and data calibration should refer to Dr. Zhang's article. Total RNA was extracted from the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid sample of a patient via the RNeasy Plus Universal Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Following by the RNA library construction via SMARTer Stranded Total RNA-Seq Kit v2 (TaKaRa, Dalian, China). Paired-end (150 bp) sequencing of the RNA library was performed on the MiniSeq platform (Illumina).

Sequencing reads were first adaptor- and quality-trimmed using the Trimmomatic program.13 The remaining reads (56, 565, 928 reads) were assembled de novo using both the Megahit (version 1.1.3) and Trinity program (version 2.5.1)14 with default parameter settings. To identify possible aetiologic agents present in the sequence data, the abundance of the assembled contigs was first evaluated as the expected counts using the RSEM program implemented in Trinity. Non-human reads (23,712,657 reads), generated by filtering host reads using the human genome (human release 32, GRCh38.p13, downloaded from Gencode) by Bowtie2,15 were used for the RSEM abundance assessment.

Virus genome characterization and analysis

Understanding the structure-function correlation in viruses is important for finding potential antiviral inhibitors and vaccine targets. Databases and bioinformatic tools that contain genomic, proteomic, and functional information have become indispensable for virology studies. In our study, all used databases and tools were listed in Table 1. All parameter adjustments were refer to the references. Here, the processes of some important analyses would be introduced.

Table 1.

Database and bioinformatic tools for virology studies.

| Tool name | Function | URL | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| GeneMark | ORF identification | http://opal.biology.gatech.edu/GeneMark/genemarks.cgi | 16 |

| ORF Finder | ORF identification | http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gorf/gorf.html | 17 |

| BLAST | Homology searching | http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/ | N/A |

| SMART | Pattern/motif recognition | http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/ | 18 |

| IEDB | Epitope analysis | http://www.immuneepitope.org | 19 |

| SPLIT 4.0 | Protein secondary structure prediction | http://split.pmfst.hr/split/4/ | 20 |

| SWISS-MODEL | 3-D structure modeling | http://swissmodel.expasy.org/ | 21 |

| I-TASSER | 3-D structure modeling | https://zhanglab.ccmb.med.umich.edu/ | 22 |

| Drugbank | Drug prediction | https://www.drugbank.ca/ | 23 |

| SeeSAR | Drug prediction | https://www.biosolveit.de/SeeSAR/ | N/A |

GeneMark, within an iterative Hidden Markov model based algorithm, the accuracy of gene start prediction can be improved by combining models of protein-coding and non-coding regions and models of regulatory sites near gene start. It can be used for a newly sequenced prokaryotic genome prediction utilizing a non-supervised training procedure. After the ORF prediction, the homologous comparison was performed with the FASTA amino acid sequence. In “Choose Search Set”, the non-redundant protein sequences database was chosen without organism and exclude conditions. In “Program Selection”, the blastp (protein-protein BLAST) algorithm was chosen. Then the distance tree was constructed with a fast minimum evolution method. The max seq difference is 0.85. The distance was Grishin.

Drug screening was conducted for each ORF coding sequence in the Sequence Search module of DrugBank using the FASTA format sequence. The BLAST parameters were acquiescent. The value of cost to open or extend a gap is -1, the value of penalty for mismatch is -3, the expectation value is 0.00001 and the reword for match is 1. Perform gapped alignment and filter query sequence (DUST & SEG) should be checked. Then the molecular docking simulations of proteins and drug molecules were performed by SeeSAR. The affinities, phys-chem properties, torsional ‘heat’ and explorable space were calculated to assess the possibility of interaction between protein and drug.

Result

Homology between SARS-CoV-2 and other CoVs

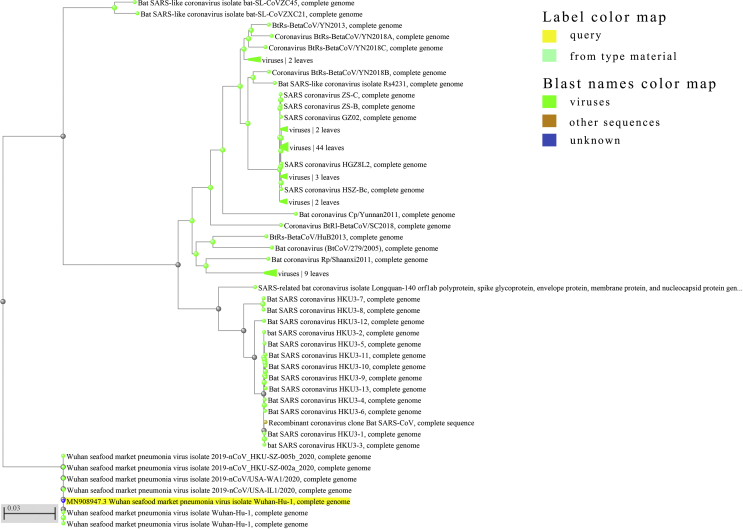

To rapidly understand the genomic characteristic and determine the evolutionary relationships, genome homologous alignments with previously identified CoVs are significant to perform. The whole genome sequence of SARS-CoV-2 (NC_045512, 29903bp ssRNA) provided by Dr. Zhang was recorded by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). We estimated phylogenetic trees based on the nucleotide sequences of the whole genome sequence (Fig. 1). The alignment result suggested that there is a significant difference between the whole genomes of SARS-CoV-2 and other CoVs. Even the most homologous species just have less than 90% repetitive sequence (Bat SARS-like coronavirus isolate bat-SL-CoVZC45 and CoVZXC21, complete genome). Furthermore, the result displayed that SARS and SARS-CoV-2 are distantly related (<82.34%). It may conclude that the new virus is not evolved directly from SARS, but we cannot deny that there is a potential relation between the two viruses.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic trees of CoVs whole genome. The tree method is fast minimum evolution and the maximum sequencing difference is 0.75.

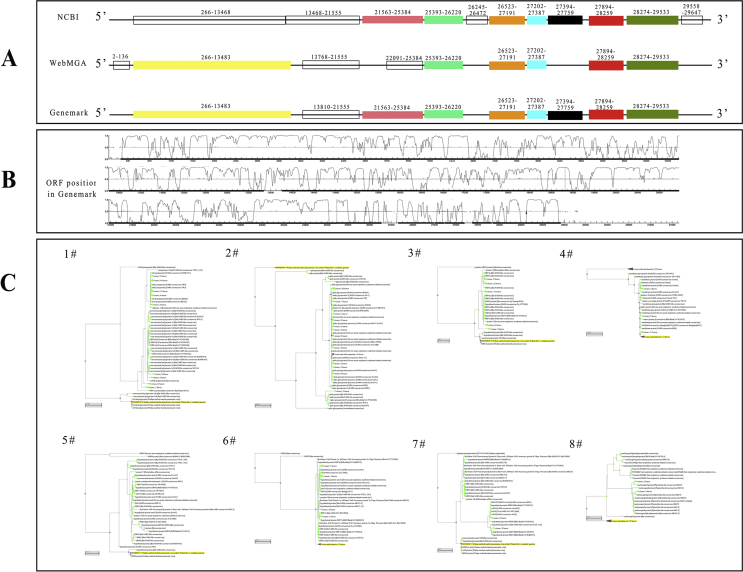

As well known, once the virus infects the host, the genetic material leaves the capsid followed by replicates and assembles. Since the presence of subgenome in CoVs, the genome of new assembled CoVs might be changed. Address this issue, the phylogenetic trees of every main ORF should be constructed. By prediction of ORFs in 3 mainstream databases (NCBI, GeneMark and WebMGA), a total of 15 ORFs were identified (Fig. 2A and B). Interestingly, at the position from 266 to 21555, each database predicts a different outcome. What's more, the most important non-structural protein orf1a/b was encoded based on this sequence. To ensure the accuracy of the subsequent analysis, a total of 8 ORFs (1#266-13483, 2#21563-25384, 3#25393-26220, 4#26523-27191, 5#27202-27387, 6#27394-27759, 7#27894-28259 and 8#28274-29533) were predicted by at least two databases would become objects for further study.

Figure 2.

All predicted ORFs in SARS-CoV-2. (A) The sketch map of all ORFs in the genome. The whole genome was predicted by NCBI, WebMGA and Genemark databases, respectively. The color boxes represent different ORFs appeared in at least 2 databases. The hollow boxes represent the ORFs which just appeared one time. (B) The peak figure of the ORF position in Genemark. The position where the fluctuation occurs represents ORF. (C) The phylogenetic trees of each ORF. The tree method is fast minimum evolution and the maximum sequencing difference is 0.75. The yellow item represents each specific ORF in SARS-CoV-2.

The phylogenetic trees based on the amino acid sequence of each ORF were constructed (Fig. 2C and Table S1). It was confirmed that the most homologous species with 1#ORF is non-structural polyprotein 1 ab of bat SARS-like CoVs (95.39%); 2# ORF vs. spike protein of bat SARS-like CoVs (81%); 3# ORF vs. nonstructural protein NS3 of bat CoVs (97.82%); 4# ORF vs. membrane protein of bat SARS-like CoVs (98.65%); 5# ORF vs. hypothetical protein of bat SARS-like CoVs (93.44%); 6# ORF vs. nonstructural protein NS7a of bat CoVs (97.52%); 7# ORF vs. hypothetical protein of bat SARS-like CoVs (94.21%); 8# ORF vs. nucleocapsid protein of bat CoVs (99.05%). Above all, although the whole genome of SARS-CoV-2 is distant from other CoVs, each ORF of SARS-CoV-2 has higher homology with bat CoVs or bat SARS-like CoVs.

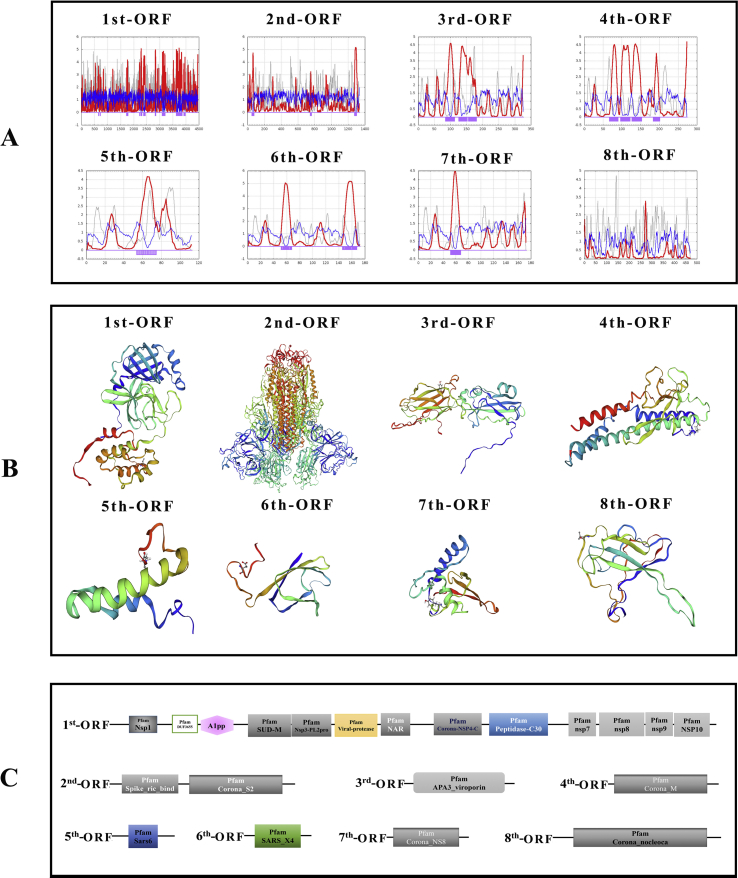

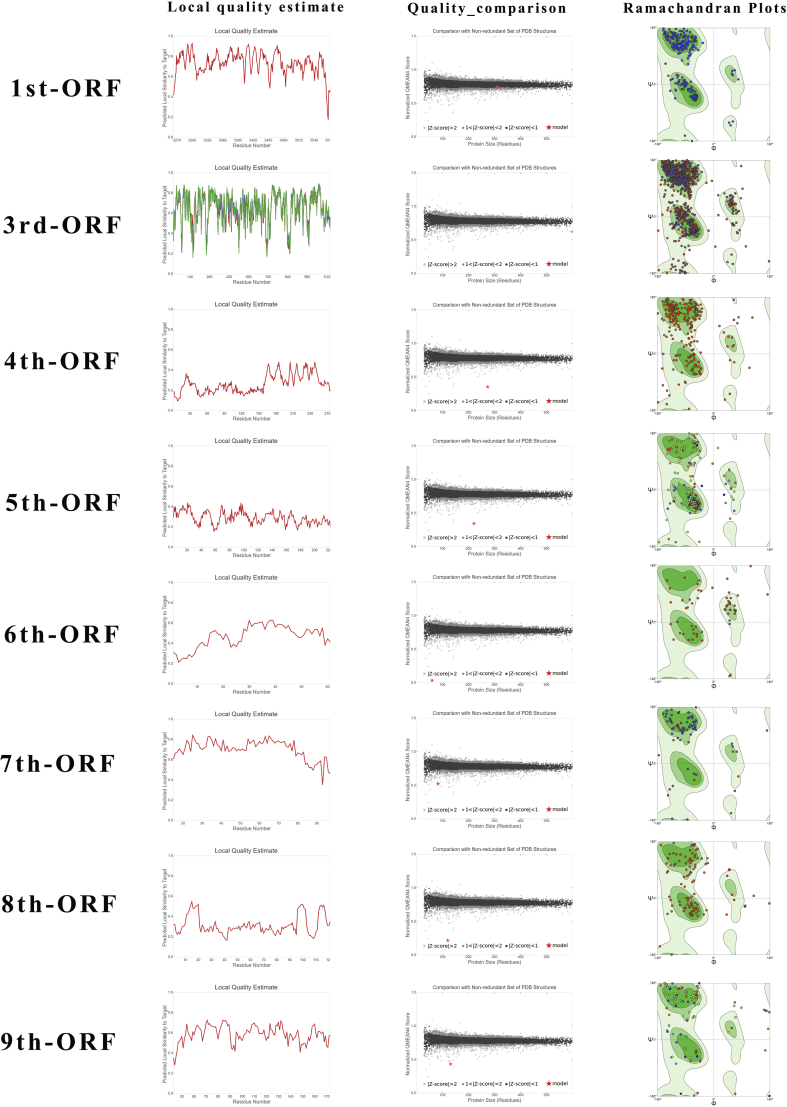

Structure and function of ORF

According to the result of phylogenetic trees, it was found that each ORF was similar to the specific genes in other CoVs like SARS, yet the differences are real. To confirm the structure and function of polypeptide chains encoded by each ORF, the secondary and tertiary structure of polypeptide were predicted (Fig. 3A, B and S1). In 1#ORF, 21 positions of transmembrane helix were identified (643–657; 700–716; 1723–1739; 1758–1773; 2219–2235; 2276–2310; 2379–2409; 2414–2438; 2822–2846; 3090–3118; 3127–3152; 3172–3202; 3630–3658; 3662–3676; 3684–3711; 3732–3750; 3758–3772; 3794–3822; 3826–3853; 3916–3932; 3961–3976); 3 helixes in 2#ORF (50–74; 748–762; 1275–1299); 3 helixes in 3#ORF (85–112; 126–151; 156–180); 4 helixes in 4#ORF (67–89; 97–121; 127–152; 184–200); 1 helix in 5#ORF (54–74); 2 helixes in 6#ORF (52–67; 146–167); 1 helix in 7#ORF (52–67) and no helix was detected in 8#ORF. The polypeptides with transmembrane helix may play role in virus infection and the transmembrane domains can be recognized by the immune system. They are good candidates for inclusion in viral vaccines. Subsequently, based on the recorded protein templates in the RCSB PDB database, homology modeling of each polypeptide was performed in SWISS-MODEL. Particularly in the modeling of 3# polypeptide, 3 subunits assemble into a protein named Spike protein (S protein) in other CoVs. S protein was often regarded as the most important structural element play a significant role in antigen recognition. When homology modeling of these 8 polypeptides, only 1#, 2#, 6# and 8# polypeptide could be matched to similar templates (seq identity>90%) while the others cannot match a template with credible identity (>30%). The result may signify 3#, 4#, 5# and 7# polypeptides may fold into novel proteins.

Figure 3.

Structural and functional prediction of each ORFs. (A) The secondary structure of each polypeptide. The red line represents the transmembrane helix preference (THM index); the blue line represents beta preference (BET index); the gray line represents the modified hydrophobic moment index (INDA index); the violet boxes represent predicted transmembrane helix position (DIG index). (B) The tertiary structure of each polypeptide (3D view). C, Domain of each ORF.

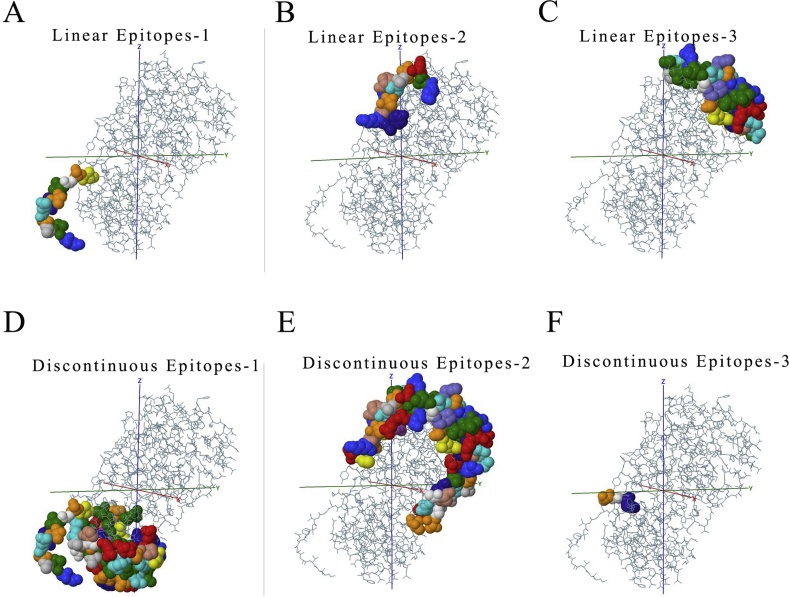

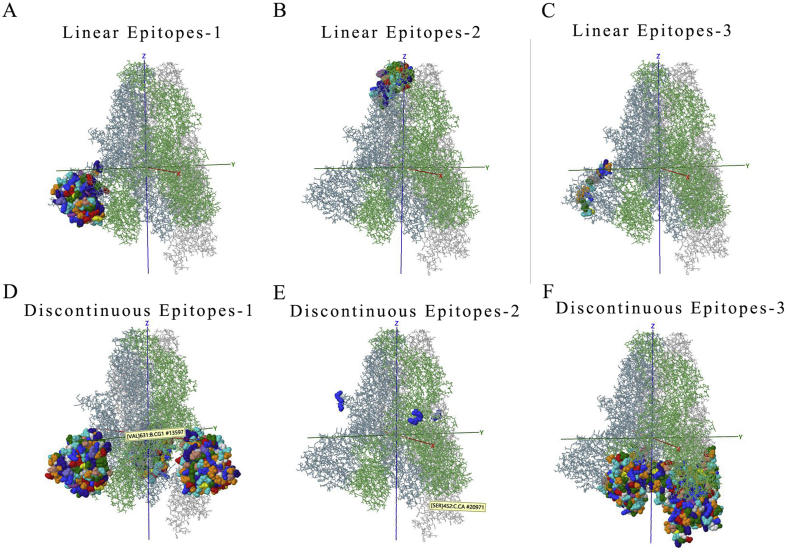

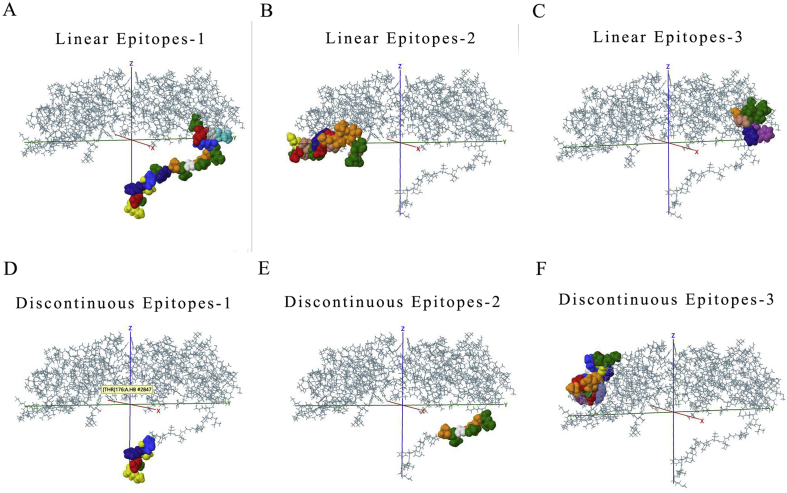

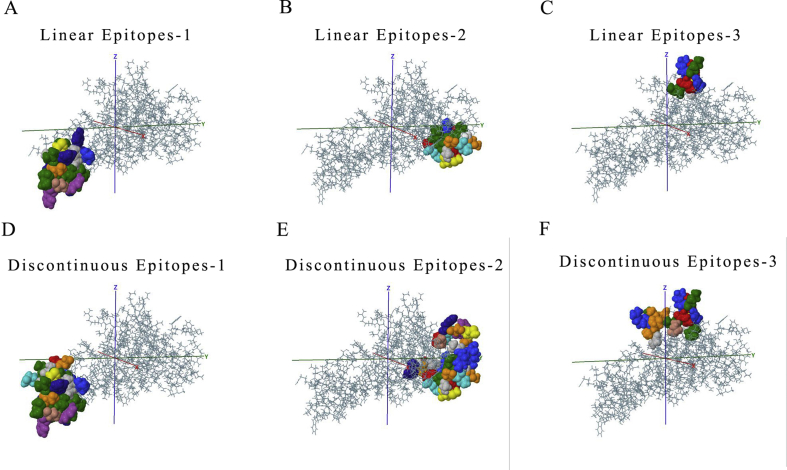

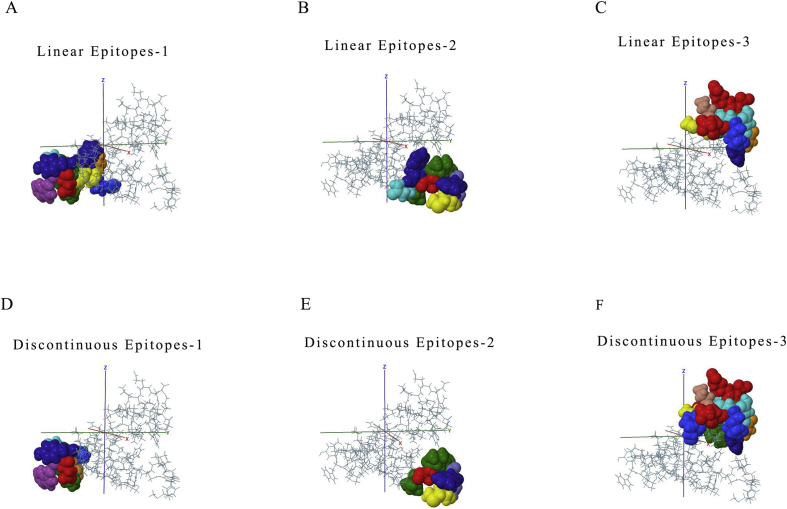

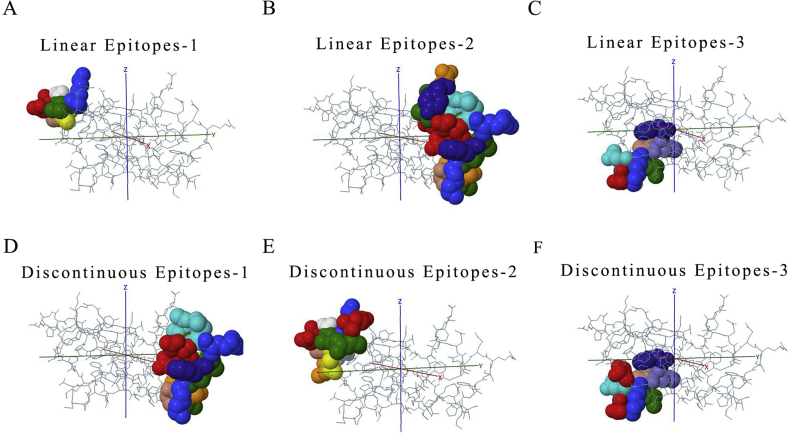

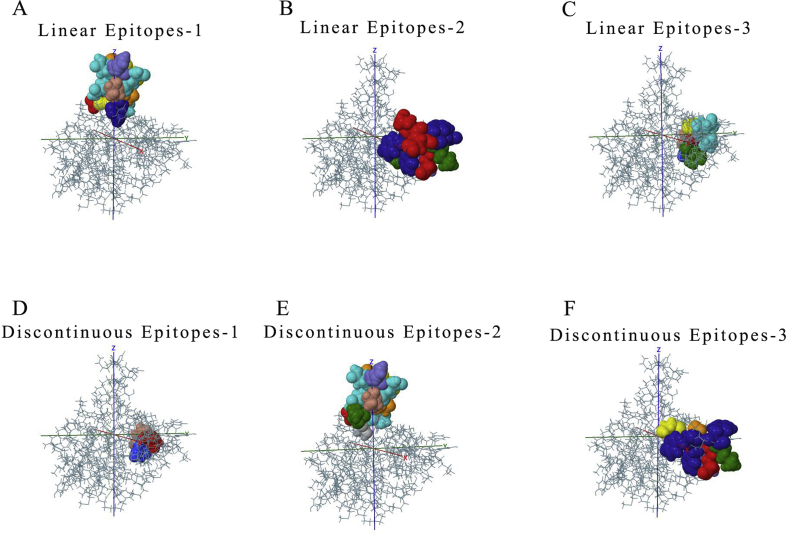

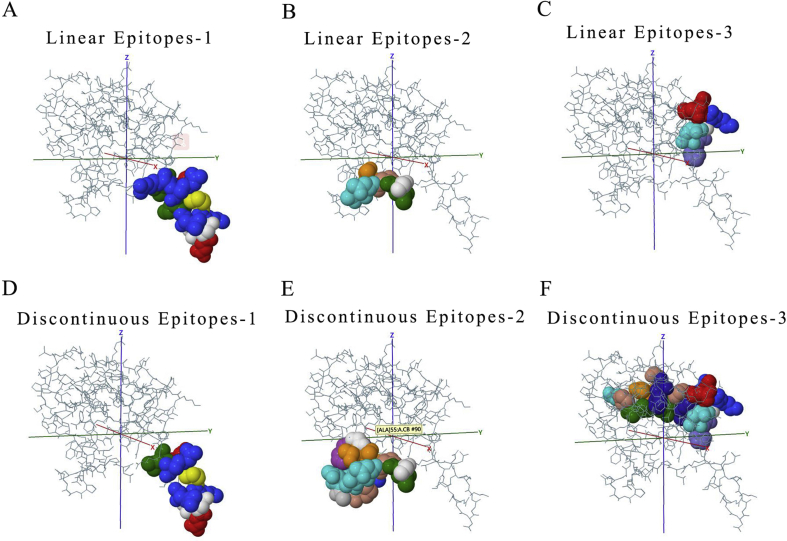

The function of polypeptide and mature protein not only depends on secondary structure and tertiary structure. The domains constituted by specific amino acid sequences are also crucial. Therefore, the main domains in each ORFs were predicted via the SMART database (Fig. 3C and Table 2). In the predicted result, it was identified that some domains play key roles in entry into the host cell like Spike_rec_bind domain in 2# ORF (Spike protein). Once CoVs infected host, immune response appeared. Thus, the prediction of epitopes, the parts of antigens interacting with receptors of the immune system are important for understanding viral diseases and finding anti-viral targets. The top3 B cell-linear and discontinuous epitopes of each polypeptide have been shown (Figure S2–9).

Table 2.

The function of each domain in ORFs.

| No. ORF | Domain name | Function | Reference or GO item |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1#ORF | Nsp1 | Mediate RNA replication and processing | 24 |

| 1#ORF | DUF3655 | Identifies the N terminus of Nsp3 | N/A |

| 1#ORF | A1pp | Bind ADP-ribose | 25,26 |

| 1#ORF | SUD-M | Identifies Nsp3 | 27 |

| 1#ORF | Nsp3_PL2pro | cysteine-type endopeptidase activity | 27, GO:0004197 |

| 1#ORF | Viral_protease | proteolytic processing of the replicase polyprotein, transferase activity, cysteine-type endopeptidase activity, omega peptidase activity | GO:0016740, GO:0004197, GO:0008242 |

| 1#ORF | NAR | nucleic acid binding | 28, GO:0003676 |

| 1#ORF | Corona_NSP4_C | involved in protein-protein interactions | 29 |

| 1#ORF | Peptidase_C30 | viral protein processing | 30, GO:0019082 |

| 1#ORF | Nsp7 | transferase activity, cysteine-type endopeptidase activity, omega peptidase activity | GO:0016740, GO:0004197, GO:0008242 |

| 1#ORF | Nsp8 | cysteine-type endopeptidase activity, transferase activity, omega peptidase activity | GO:0004197, GO:0016740, GO:0008242 |

| 1#ORF | Nsp9 | viral genome replication, RNA binding | GO:0019079, GO:0003723 |

| 1#ORF | Nsp10 | viral genome replication, zinc ion binding, RNA binding | GO:0019079, GO:0008270, GO:0003723 |

| 2#ORF | Spike_rec_bind | aids viral entry into the host cell | 31 |

| 2#ORF | Corona_S2 | receptor-mediated virion attachment to host cell, membrane fusion an integral component of membrane, viral envelope |

GO:0046813, GO:0061025, GO:0016021, GO:0019031 |

| 3#ORF | APA3_viroporin | modulate virus release | 32,33 |

| 4#ORF | Corona_M | implicated in virus assembly, viral life cycle | 32, GO:0019058 |

| 5#ORF | Sars6 | 42 to 63 amino acids, uncharacterised | N/A |

| 6#ORF | SARS_X4 | binding activity to integrin I domains | 33 |

| 7#ORF | Corona_NS8 | typically between 39 and 121 amino acids, uncharacterised | N/A |

| 8#ORF | Corona_nucleoca | viral nucleocapsid | 34, GO:0019013 |

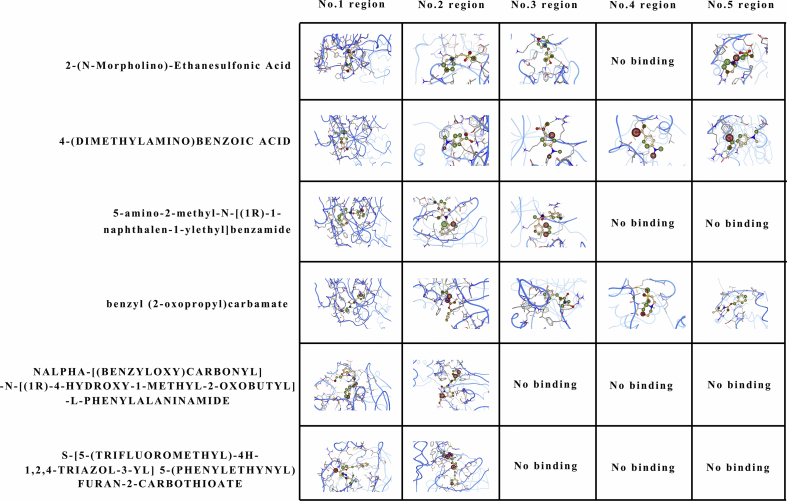

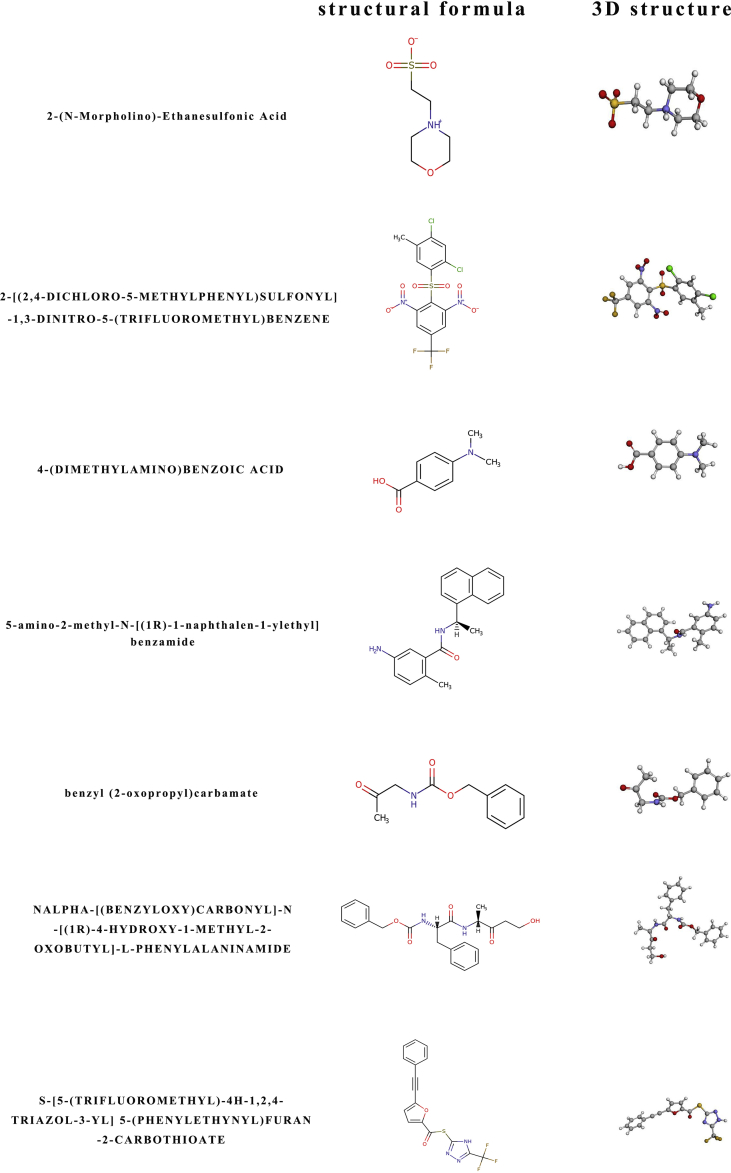

Targeted drug prediction

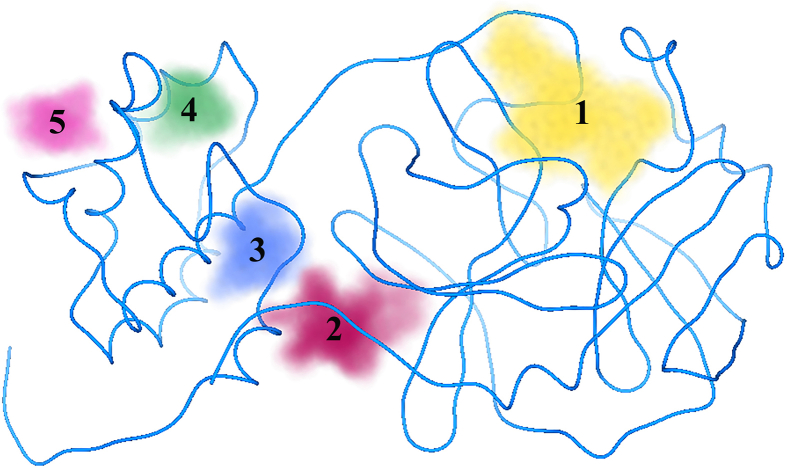

Although the genome function was analyzed and the process of CoVs proliferation has been well known. The screening of medicable drugs remains a problem. To achieve the purpose of treatment in the shortest possible time, screening existing drugs is more practical than designing new ones. According to amino acid sequence searching result of each polypeptide, only 1# polypeptide could be bound with the 7 known drugs (2-(N-morpholino)-ethanesulfonic acid; 2-[(2,4-dichloro-5-methylphenyl)sulfonyl]-1,3-dinitro-5-(trifluoromrthyl)benzene; 4-(dimethylamino)benzoic acid; 5-amino-2-methyl-N-[(1R)-1-naphthalen-1-ylethyl]benzamide; benzyl (2-oxopropyl)carbamate; nalpha-[(benzyloxy)carbonyl]-N-[(1R)-4-hydroxy-1-methyl-2-oxobutyl]-l-phenylalaninamide and S-[5-(trifluoromethyl)-4H-1,2,4-triazol-3-YL] 5-(phenylethynyl)furan-2-carbothioate) (Figure S10). To further verify the ability of drug binding with peptide, 5 binding regions were detected by SeeSAR software (Figure S11). Via calculated affinities, phys-chem properties, torsional ‘heat’ and explorable space, a comprehensive analysis of the binding capacity of each drug with a specific binding region was performed (Fig. 4). It was shown that (2-(N-morpholino)-ethanesulfonic acid could bind with No. 1, 2, 3 and 5 regions with a set of desired parameters. Both 4-(dimethylamino) benzoic acid and benzyl (2-oxopropyl) carbamate could bind with all regions even without ideal parameters. All 7 drugs were tried to be used for curing SARS, but the efficacy and mechanism are still uncertain.

Figure 4.

3D view of each drug binding site within 1# polypeptide. The blue line represents the peptide chain. In the centre of each little diagram is the drug molecule. The blank space means that the drug cannot bind with the peptide chain. The dotted lines represent intermolecular forces.

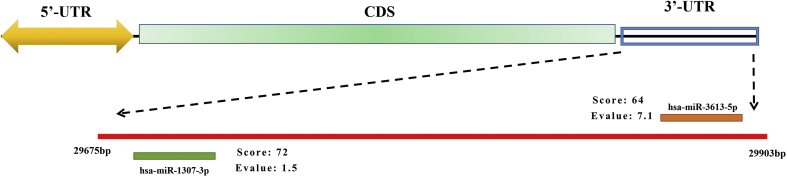

In addition to the identified ORFs, in the whole genome, there are 2 UTRs located at 5′ end and 3′ end respectively. As well known, the proliferation of viruses often requires to borrow the transcription and translation systems within host cells. Thus, it was supposed that miRNAs in host cells might bind to the virus which results in RNA degradation and inhibited translation. In the miRBase database, through sequence prediction, miR-1307-3p and miR-3613-5p may bind to 3′-UTR of SARS-CoV-2s. Interestingly, previous studies have detected in lung cancer patients, both miR-1307-3p and miR-3613-5p were downregulated significantly.35,36 Furthermore, it was demonstrated tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) could upregulate miR-1307-3p which were used to treat non-small cell lung cancer37。In conclusion, both 2 miRNAs can not only become drug target, they can also be regarded as biomarkers in checking of viral pneumonia.

Discussion

Generally, a novel virus emergence often leads to major outbreaks. In December 2019, an epidemic caused by SARS-CoV-2 has claimed so many lives in China. Faced with the serious situation, a comprehensive analysis of the SARS-CoV-2 in a short time was imperative. In the present study, it was confirmed that only bat-SL-CoVZC45 and CoVZXC21 have higher homology with SARS-CoV-2 (<90%). However, each single ORF has higher homology with SARS after compared. Interestingly, the predicted outcomes of ORF were different like 266bp-21555bp region which encode the most important non-structural protein of CoVs (Fig. 2A). If there are 3 encode manners, in reality, the genome may generate 5 different species which will bring great difficulties to the therapy.

The whole process of novel drug development to clinical effect tests will spend a lot of time. Thus, if there some existing drugs could be authenticated therapeutic, it will greatly improve the prognosis of patients. A total of 7 drugs were predicted to bind with 1# polypeptide. Notably, the 1# polypeptide could form the replicase polyprotein 1a (ORF1a).38 Normally, ORF1a and ORF1b (transcriptase) often form a heterodimer (ORF1ab) which may serve specific roles in virulence, virus-cell interactions and alterations of defense response. In ORF1a, the detailed analysis revealed evidence of adaptive mutations exceeded structural proteins.39 For example, the ORF1a polyprotein showed a rate of nonsynonymous substitutions similar to that in the S gene. Among the screened drugs, the 2-(N-morpholino)-ethanesulfonic acid has the best binding efficiency with ORF1a through the 3D structural fitting. Unfortunately, this hypothesis lacks enough evidence. Furthermore, 2-(N-Morpholino)-ethanesulfonic acid is known as a component of crystallization buffer. Such buffer molecules including Tris, Hepas, glycerinum, DMSO and water usually appear in crystal structures but make no sense for drug discovery of virus. Thus, though the predicted results of 2-(N-Morpholino)-ethanesulfonic acid were ideal, it dose not mean 2-(N-Morpholino)-ethanesulfonic acid own effective virus suppression. In contrast, both benzyl (2-oxopropyl) carbamate and 4-(dimehylamina) benzoic acid have bene demonstrated to inhibit SARS-CoV infection effectively.40,41 Strangely, the 2-[(2,4-dichloro-5-methylphenyl)sulfonyl]-1,3-dinitro-5-(trifluoromrthyl)benzene could not bind with any region in 1# polypeptide which may be caused by 2 reasons: 1, It has bigger molecular weight and a more complicated structure, results in a lower affinity with the polypeptide. 2, there are 2 chlorine atoms in this drug which might lead to a weakened recognized ability between drug and peptide chain.

Fundamentally, the host defense against viral infection dependent on the individual immune system. Therefore, the identification of viral antigens is also very important, which is also a prerequisite for successful vaccine development. In our study, the B cell epitope of each peptide chain has been predicted for a better understanding of the infection process of SARS-CoV-2. Finally, as a Chinese and survival of this disaster. I hope what I have learned will help China tide over the difficulties. Come on, China. Come on, Wuhan.

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr. Zhang for providing the genome sequence of SARS-CoV-2. We should also thank Yuqing Chen, Minglu Niu and Luyao Zhao for reference providing and relevant analysis of the virus and potential drugs. This study cannot go well without the help of these experts.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chongqing Medical University.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gendis.2020.04.002.

Contributor Information

Long Chen, Email: chenlong19910522@163.com.

Li Zhong, Email: zhongli001122@126.com.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

figs1.

figs2.

figs3.

figs4.

figs5.

figs6.

figs7.

figs8.

figs9.

figs10.

figs11.

figs12.

References

- 1.Wang L.F., Shi Z., Zhang S., Field H., Daszak P., Eaton B.T. Review of bats and SARS. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(12):1834–1840. doi: 10.3201/eid1212.060401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ge X.Y., Li J.L., Yang X.L. Isolation and characterization of a bat SARS-like coronavirus that uses the ACE2 receptor. Nature. 2013;503(7477):535–538. doi: 10.1038/nature12711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen Y., Guo D. Molecular mechanisms of coronavirus RNA capping and methylation. Virol Sin. 2016;31(1):3–11. doi: 10.1007/s12250-016-3726-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cui J., Li F., Shi Z.L. Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. 2019;17(3):181–192. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0118-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cauchemez S., Van Kerkhove M.D., Riley S., Donnelly C.A., Fraser C., Ferguson N.M. Transmission scenarios for Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) and how to tell them apart. Euro Surveill :Bull Eur Sur Les Mal Transmissibles Eur Commun Dis Bull. 2013;18(24) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Y., Liu Q., Guo D. 2020. Emerging Coronaviruses: Genome Structure, Replication, and Pathogenesis. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Snijder E.J., van der Meer Y., Zevenhoven-Dobbe J. Ultrastructure and origin of membrane vesicles associated with the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus replication complex. J Virol. 2006;80(12):5927–5940. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02501-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hussain S., Pan J., Chen Y. Identification of novel subgenomic RNAs and noncanonical transcription initiation signals of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J Virol. 2005;79(9):5288–5295. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.9.5288-5295.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ziebuhr J., Snijder E.J., Gorbalenya A.E. Virus-encoded proteinases and proteolytic processing in the Nidovirales. J Gen Virol. 2000;81(Pt 4):853–879. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-4-853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Masters P.S. The molecular biology of coronaviruses. Adv Virus Res. 2006;66:193–292. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(06)66005-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shi S.T., Lai M.M. Viral and cellular proteins involved in coronavirus replication. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2005;287:95–131. doi: 10.1007/3-540-26765-4_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ogilvie L.A., Jones B.V. The human gut virome: a multifaceted majority. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:918. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bolger A.M., Lohse M., Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(15):2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grabherr M.G., Haas B.J., Yassour M. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29(7):644–652. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Langmead B., Salzberg S.L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012;9(4):357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lukashin A.V., Borodovsky M. GeneMark.hmm: new solutions for gene finding. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26(4):1107–1115. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.4.1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rombel I.T., Sykes K.F., Rayner S., Johnston S.A. ORF-FINDER: a vector for high-throughput gene identification. Gene. 2002;282(1–2):33–41. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00819-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Letunic I., Bork P. 20 years of the SMART protein domain annotation resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(D1):D493–D496. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vita R., Mahajan S., Overton J.A. The immune epitope database (IEDB): 2018 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D339–D343. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Juretic D., Zoranic L., Zucic D. Basic charge clusters and predictions of membrane protein topology. J Chem Inf Comput Sci. 2002;42(3):620–632. doi: 10.1021/ci010263s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Waterhouse A., Bertoni M., Bienert S. SWISS-MODEL: homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(W1):W296–W303. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang J., Zhang Y. I-TASSER server: new development for protein structure and function predictions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(W1):W174–W181. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wishart D.S., Feunang Y.D., Guo A.C. DrugBank 5.0: a major update to the DrugBank database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(D1):D1074–D1082. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Almeida M.S., Johnson M.A., Herrmann T., Geralt M., Wuthrich K. Novel beta-barrel fold in the nuclear magnetic resonance structure of the replicase nonstructural protein 1 from the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J Virol. 2007;81(7):3151–3161. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01939-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hassa P.O., Haenni S.S., Elser M., Hottiger M.O. Nuclear ADP-ribosylation reactions in mammalian cells: where are we today and where are we going? Microbiol Mol Biol Rev : MMBR (Microbiol Mol Biol Rev) 2006;70(3):789–829. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00040-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karras G.I., Kustatscher G., Buhecha H.R. The macro domain is an ADP-ribose binding module. EMBO J. 2005;24(11):1911–1920. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Snijder E.J., Bredenbeek P.J., Dobbe J.C. Unique and conserved features of genome and proteome of SARS-coronavirus, an early split-off from the coronavirus group 2 lineage. J Mol Biol. 2003;331(5):991–1004. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00865-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Serrano P., Johnson M.A., Chatterjee A. Nuclear magnetic resonance structure of the nucleic acid-binding domain of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus nonstructural protein 3. J Virol. 2009;83(24):12998–13008. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01253-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manolaridis I., Wojdyla J.A., Panjikar S. Structure of the C-terminal domain of nsp4 from feline coronavirus. Acta Crystallogr Sect D Biol Crystallogr. 2009;65(Pt 8):839–846. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909018253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anand K., Palm G.J., Mesters J.R., Siddell S.G., Ziebuhr J., Hilgenfeld R. Structure of coronavirus main proteinase reveals combination of a chymotrypsin fold with an extra alpha-helical domain. EMBO J. 2002;21(13):3213–3224. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prabakaran P., Gan J., Feng Y. Structure of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus receptor-binding domain complexed with neutralizing antibody. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(23):15829–15836. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600697200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Armstrong J., Niemann H., Smeekens S., Rottier P., Warren G. Sequence and topology of a model intracellular membrane protein, E1 glycoprotein, from a coronavirus. Nature. 1984;308(5961):751–752. doi: 10.1038/308751a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hanel K., Stangler T., Stoldt M., Willbold D. Solution structure of the X4 protein coded by the SARS related coronavirus reveals an immunoglobulin like fold and suggests a binding activity to integrin I domains. J Biomed Sci. 2006;13(3):281–293. doi: 10.1007/s11373-005-9043-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parker M.M., Masters P.S. Sequence comparison of the N genes of five strains of the coronavirus mouse hepatitis virus suggests a three domain structure for the nucleocapsid protein. Virology. 1990;179(1):463–468. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90316-J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Song J., Wang W., Wang Y. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition markers screened in a cell-based model and validated in lung adenocarcinoma. BMC Canc. 2019;19(1):680. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-5885-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zheng Y., Fu X., Wang L. Comparative analysis of MicroRNA expression in dog lungs infected with the H3N2 and H5N1 canine influenza viruses. Microb Pathog. 2018;121:252–261. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2018.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garcia-Donas J., Beuselinck B., Inglada-Perez L. Deep sequencing reveals microRNAs predictive of antiangiogenic drug response. JCI insight. 2016;1(10) doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.86051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chan J.F., Kok K.H. Genomic characterization of the 2019 novel human-pathogenic coronavirus isolated from a patient with atypical pneumonia after visiting Wuhan. 2020;9(1):221–236. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1719902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Graham R.L., Sparks J.S., Eckerle L.D., Sims A.C., Denison M.R. SARS coronavirus replicase proteins in pathogenesis. Virus Res. 2008;133(1):88–100. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Verschueren K.H., Pumpor K., Anemuller S., Chen S., Mesters J.R., Hilgenfeld R. A structural view of the inactivation of the SARS coronavirus main proteinase by benzotriazole esters. Chem Biol. 2008;15(6):597–606. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bacha U., Barrila J., Gabelli S.B., Kiso Y., Mario Amzel L., Freire E. Development of broad-spectrum halomethyl ketone inhibitors against coronavirus main protease 3CL(pro) Chem Biol Drug Des. 2008;72(1):34–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2008.00679.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.