The ongoing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak may be associated with direct and indirect adverse consequences on the heart. Besides severe pneumonia, myocarditis and myocardial injury have been suspected as additional causes of death in patients affected by COVID-19 [1]. However, as recently reported by Q. Deng et al. troponin levels were increased particularly in patients who died during hospitalization although they did not present with typical signs of myocarditis [2].

Another indirect consequence of this pandemic is the way in which it may adversely affect the efficiency and effectiveness of the network organization required to offer primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI) to the patients presenting with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), within appropriate time frames. There are already reports from China of delays in the presentation and treatment of STEMI [3] which may eventually exert an indirect disruptive impact on outcomes.

Recommendations on how to treat STEMI patients with or without a COVID-19 infection have been issued in countries with a massive virus outbreak [4].

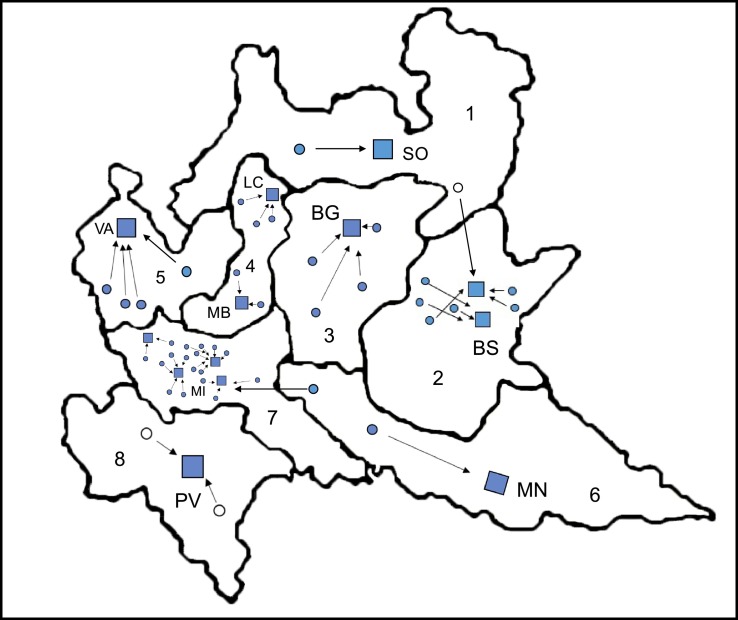

Lombardy is the most densely populated region in Italy, with approximately 10 million inhabitants, and is at the moment striving with COVID-19. With regard to the STEMI network, the healthcare system is divided in 8 areas, with an overall availability of 55 catheterization laboratories, performing 24/7 PPCI (Fig. 1 ) and a well established network for the treatment of STEMI. Since February 21st 2020, healthcare operators in the region faced an exponential rise of COVID-19 patients, leading to an increased number of subjects requiring hospitalization, and a subsequent overload of the intensive care units (ICUs).

Fig. 1.

Map with geographical location of the eight areas of the Lombardy Region with the estimated resident population: 1 (mountain region, 298,000); 2 (1,145,000); 3 (1,115,000); 4 (1,200,000); 5 (1,430,000); 6 (773,000); 7 (3,480,000); 8 (546,000). SO = Sondrio; BS = Brescia; BG = Bergamo; LC = Lecco; MB = Monza; VA = Varese; MN = Mantova; MI = Milano; PV=Pavia.

The squares indicate the “Macro-hubs” identified during the pandemic. The full circles represent the “hub” hospitals before the pandemic that have been converted to spoke. The empty circles represent hospitals that were “spoke” even before the outbreak. Arrows indicate the referral “macro-hub” of each spoke.

To face the emergency, most hospitals underwent a sudden, yet radical, transformation: all deferrable surgical and interventional procedures were delayed, the number of ICUs capacity was exponentially increased, and most departments (including coronary care units) were converted to COVID-19 units.

On March 8th, the decree of the healthcare Authorities of Lombardy [5] urged a change in all the regional networks for the treatment of time-dependent clinical and surgical emergencies (STEMI, stroke, major traumas, neurological, cardiac and vascular surgical emergencies) to concentrate personnel and urgent activities in few centers while expanding health resources for COVID-19 patients, and simultaneously to avoid default of hospitals due to general overload.

A model of centralization to some “Macro-Hubs” was applied: for patients with STEMI, one or two Macro-Hub were identified in each area, according to the estimated transportation time of patients, geographical features and capacity to admit all the potential patients. The following requirements were further considered for potential Macro-hubs: to perform PPCI to all incoming STEMI, 24/7; to guarantee a PPCI team (interventional cardiologists, nurses and related staff) that would be available in hospital 24/7 and not on call; to provide internal, dedicated and separated, pathways for STEMI patients with suspected/diagnosed COVID-19 disease from triage, through catheterization laboratory to isolated care units, in order to reduce cross-infection rate at each step of the care process, and to guarantee a convenient protection of the healthcare professionals. Finally, the staff of the spoke hospitals were required to cooperate with the hub, to deliver the aforementioned level of care.

Thus, thirteen “Macro-hub” were identified, with a 63% reduction in the number of hubs compared to pre-pandemic setting; the number of spoke centers per macro-hub was different inside each area (Fig. 1). This model of STEMI centralization was established to keep the regional healthcare system from being overwhelmed, and to guarantee at the same time standard levels of care to the patients trying to prevent the indirect adverse outcome on the heart related to the COVID-19 outbreak. Although this system may not be entirely applicable to different geographical areas or preexisting networks, it may portend a model for other countries. The disease is spreading, and every State should be prepared even to drastic pre-emptive actions to maintain the quality of STEMI care [6]. Staring at the sea is not the best strategy to fight a tsunami.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors report no relationships that could be construed as a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Du R.H., Liang L.R., Yang C.Q. Predictors of mortality for patients with COVID-19 pneumonia caused by SARS-CoV-2: a prospective cohort study. Eur. Respir. J. 2020 doi: 10.1183/13993003.00524-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deng Q., Hu B., Zhang Y. Suspected myocardial injury in patients with COVID-19: evidence from front-line clinical observation in Wuhan, China. Int. J. Cardiol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2020.03.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tam C.F., Cheung K.S., Lam S. Impact of Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak on ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction care in Hong Kong, China. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes. 2020 Mar 17 doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.120.006631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zeng J., Huang J., Pan L. How to balance acute myocardial infarction and COVID-19: the protocols from Sichuan Provincial People’s Hospital. Intensive Care Med. 2020 Mar 11 doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05993-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.https://www.regione.lombardia.it/wps/wcm/connect/5e0deec4-caca-409c-825b-25f781d8756c/DGR+2906+8+marzo+2020.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CACHEID=ROOTWORKSPACE-5e0deec4-caca-409c-825b-25f781d8756c-n2.vCsc

- 6.Ardati A.K., Mena Lora A.J. Be prepared. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes. 2020;13 doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.120.006661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]