Abstract

After the slow recovery from the 2008–2009 global financial crisis, the world economy faced slower growth than in the previous decade and even the prospect of a new global financial crisis. This paper starts by examining the reasons for the slow economic recovery and growth in the after the 2008–2009 global financial crisis and "great recession". Then, it examines the reasons the United States grew faster than other advanced countries (especially Europe and Japan), the slowing growth of emerging market economies (and even economic crisis in some of them), and whether the world is now (February 2020) sliding toward a new global financial crisis and recession.

Keywords: Growth prospects, Major advanced countries, Emerging market economies, Rising protectionism, Global financial crisis

1. Introduction

After a decade from the end of the deepest global financial crisis and recession of the post-war period, world growth continues to be slow and even falling in most countries. There is now even the risk that the world could be drifting toward a new global financial crisis and recession.

This paper examines the reasons for (1) the slow recovery of the United States after the recent global financial crisis, (2) the United States growing faster than other advanced countries (particularly Europe and Japan), (3) growth slowing in most emerging market economies, and (4) the prospects of the world facing a new global financial crisis.

2. Slow recovery and growth in the united states and other advanced countries

Table 1 shows that at the depth of the recession in 2009, the percentage fall of real GDP among the largest advanced nation ranged from 2.8 for the United States to 5.6 for Germany, and it was 4.5 in the Euro Area as a whole, 2.9 in Canada, 4.3 in the United Kingdom, and 5.4 in Japan. Despite powerful traditional and non-traditional (QE) expansionary monetary and fiscal policies, the recovery from 2010 to 2017 was slow in all advanced nations, averaging 2.1 percent in the United States, 1.3 percent in the EU-19 or Euro Area (which even fell back into recession in 2012 and 2013), 2.0 percent in the United Kingdom, 1.5 percent in Japan, and 2.3 percent in Canada. Britain and Canada fared generally better than the Euro Area and Japan since the end of the crisis, with growth rates comparable to those in the United States. Japan suffered six recessions during the past twenty-five years (including in the ones 2011 and 2014) and was facing a new recession in 2020.

Table 1.

Average annual percentage growth of real GDP in major advanced countries in 2009–2019 and forecasts for 2020–2021.

| Nation/area | Yearly Aver. |

2020a | 2021a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 2010–2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |||

| USA | −2.8 | 2.1 | 2.9 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 1.7 |

| EU-19 | −4.5 | 1.3 | 1.9 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.4 |

| Germany | −5.6 | 2.1 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 1.1 | 1.4 |

| France | −2.9 | 1.3 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| Italy | −5.5 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.7 |

| Spain | −3.6 | 0.7 | 2.4 | 2.0 | 1.6 | 1.6 |

| U.K. | −4.3 | 2.0 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.5 |

| Japan | −5.4 | 1.5 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 0.5 |

| Canada | −2.9 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 1.5 | 1.8 | 1.8 |

Forecasts. Source: IMF, 2019, IMF, 2020a, IMF, 2020b.

3. Reasons for the slow recovery and growth in the United States after the crisis

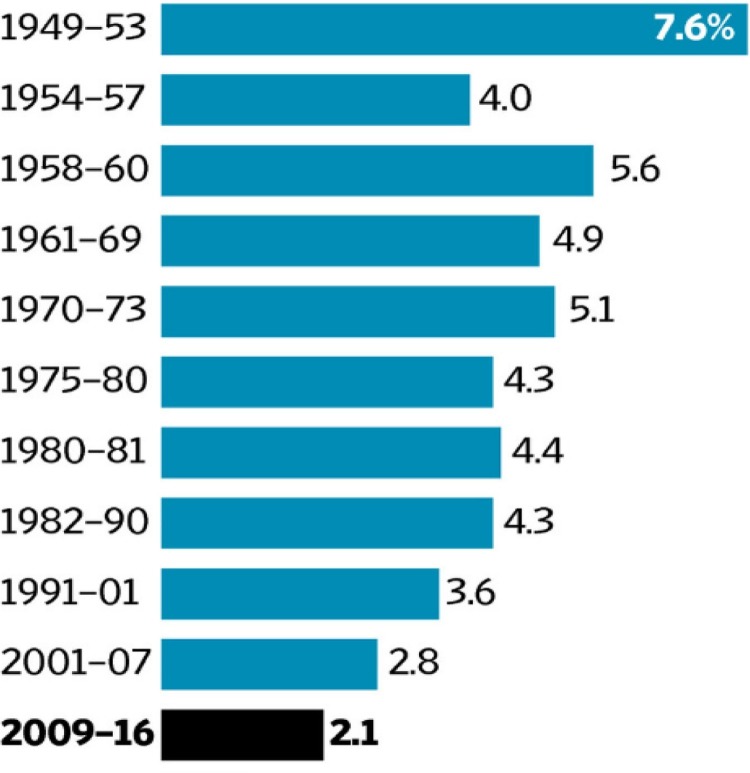

The recovery and growth from the recent global financial crisis and great recession in the United States was the slowest of all the U.S. recessions of the post-war period. Fig. 1 shows that the average yearly growth of real GDP following the 2008–2009 recession averaged only 2.1 percent over the 2009–2017 period and, as such, it was the slowest of all the 11 recession that the United States faced over the 1949–2017 period.

Fig. 1.

U.S. recovery and growth after each post-war recession.

Source: The Commerce Department (2016).

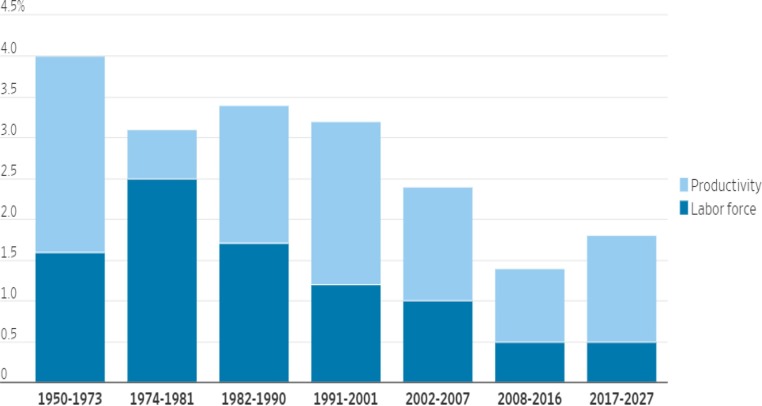

The general reasons for this are also more or less clear: a reduction in the growth of labor productivity and labor force in the United States. Fig. 2 shows that the growth of labor productivity and labor force have been smaller drivers of potential U.S. growth since the global financial crisis than in previous decades, and are expected to remain smaller in the next decade – the only exception is the slower growth of labor productivity in the 1974–1981 period.

Fig. 2.

Productivity and labor force growth as drivers of U.S. growth over time. Note: 2017–2027 are projections.

Source: Congressional Budget Office, 2017a, Congressional Budget Office, 2017b.

There are, however, some major disagreements on the more basic underlying causes for the slow U.S. growth after the crisis. Supply-siders believe that the slow U.S. growth was the result of low growth of labor productivity, excessive economic regulations, and inadequate social and physical infrastructures. Demand-siders, on the other hand, blame inadequate infrastructure investments and rising income inequalities that dampened private consumption.

4. Economic policies adopted by the Trump administration to stimulate growth

During the first three years of his administration, Trump adopted many of the growth policies that he promised on the campaign trail. On the taxation front, the Trump administration passed a tax reform bill that lowered the federal corporate rate from 35 percent to 21 percent, with personal income taxes reduced from 7 to 4 brackets of 10 percent, 25 percent, 35 percent, and 37 percent. Trump was also able to obtain funding for more infrastructure investments and the military, but not as much as he promised because of the very large increase in budget deficits and national debt that they would entail.

On the domestic regulatory front, the Trump administration rolled back parts of the Dodd–Frank Act of 2010, reduced many regulations imposed during the eight years of the Obama and of previous administrations, and repealed the individual mandate that required every employee to have health care, but he did not succeed in repealing the Affordable Care Act or Obamacare as a whole (as he had promised to do during the presidential campaign). And, as of the end of February 2020, Trump was able only to get partial funding for the wall on the Mexican border to reduce illegal migration.

On the international front, as he had promised, Trump dropped out of the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP), put the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) on hold, and dropped out of the Paris Climate Accord. He negotiated a new trade agreement with South Korea, renegotiated NAFTA (now USMCA), and is negotiating a new trade agreement with Japan. Trump also imposed a tariff of 25 percent on U.S. steel imports and a 10 percent tariff on U.S. aluminum imports from many nations. Trump also started a trade war with China by imposing a 25 percent tariff on nearly $370 billion of Chinese exports to the United States (which remained in place despite signing a “Phase-One” trade agreement with China in January 2020). This in retaliation for China's large scale and systematic stealing of U.S. intellectual property and in order to bring back some manufacturing to the United States and in the hope of reducing the huge and unsustainable U.S. trade deficit with China (White House Office of Trade and Manufacturing Policy, 2018).

Trump predicted that his policies would lift U.S. growth to more than 2.5–3.0 percent per year. As shown in Table 1, U.S. growth did indeed rise to 2.9 percent in 2018, but it then fell to 2.3 percent in 2019, and it is forecasted to be 2.0 percent in 2020 and 1.7 percent in 2021 (refer Table 1). It seems that the bump in growth in 2018 was primarily the result of the tax reform (which caused a sharp increase in the U.S. budget deficit) but this was only temporary, as it now seems that U.S. growth is reverting back to the post-crisis average of about 2.0–2.1 percent per year.

5. Slow recovery in United States, but faster than Europe's

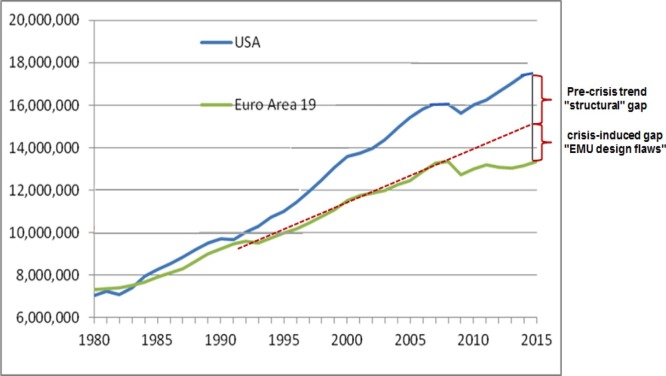

Although the U.S. recovery after the recent global financial crisis was the slowest of all its post-war recessions, it was faster than in Europe (see Fig. 3 ). The figure shows that starting at about the same level in 1983, the GDP, in Purchasing Power Parity terms (PPP) at 2014 dollars, grew more slowly in the Euro Area than in the United States (Salvatore, 1998, Salvatore, 2004, Salvatore, 2007) and that the divergence widened significantly from the start of the global financial crisis in 2008 until 2015.

Fig. 3.

The Euro Area growth crisis goes far back, but became worse after the global financial crisis.

Source: Conference Board (2014) and European Central Bank (2017).

But why was the Great Recession so deep and the recovery so slow in the United States and other advanced countries? One important reason is that the Great Recession was triggered and accompanied by a banking and financial crisis, and experience indicates (Reinhart & Rogof, 2009) that this type of crisis is much more difficult and takes much longer to overcome than a purely economic crisis because it is usually accompanied by heavy deleveraging by the banking sector. But there also other more specific reasons that made this recovery and growth so slow.

The most important of these is the sharp decline in labor productivity in advanced nations since the recent global financial crisis. Table 2 shows that while U.S. labor productivity increased at a yearly average of 2.4 percent in 1999–2006, it rose by only 1.0 percent in 2007–2018. Comparable figures (in percentages) were, respectively, 1.8 and 0.4 for Japan, 2.4 and 0.2 in the United Kingdom, 1.5 and 0.5 for the Euro Area, and 1.9 and 0.7 for the European Union of 28 (EU-28). Population growth also continued to slow down after the Great Recession considerably in most advanced nations, but again more so in Europe than in the United States. With the growth of labor productivity and labor force declining, the growth of advanced nations declined.

Table 2.

Growth of labor productivity, average percent per year, 1999–2018.

| U.S. | Japan | U.K. | Euro Area | EU-28 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999–2006 | 2.4 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 1.5 | 1.9 |

| 2007–2018 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.7 |

Source: OECD (2019).

Another reason for slower growth (and less job creation) in the United States and other advanced countries was outsourcing. Most multinational corporations from advanced nations, in their effort to minimize production costs, transferred a great deal of production (and jobs) to emerging market economies, especially China, during the past decade. This started before the recent global financial crisis but it rapidly accelerated afterwards. Rising protectionism since the Great Recession, however, caused disruptions in the global supply chains (thus reversing to some extent the globalization process) even before Trump and this slowed down growth in the United States and the rest of the world.

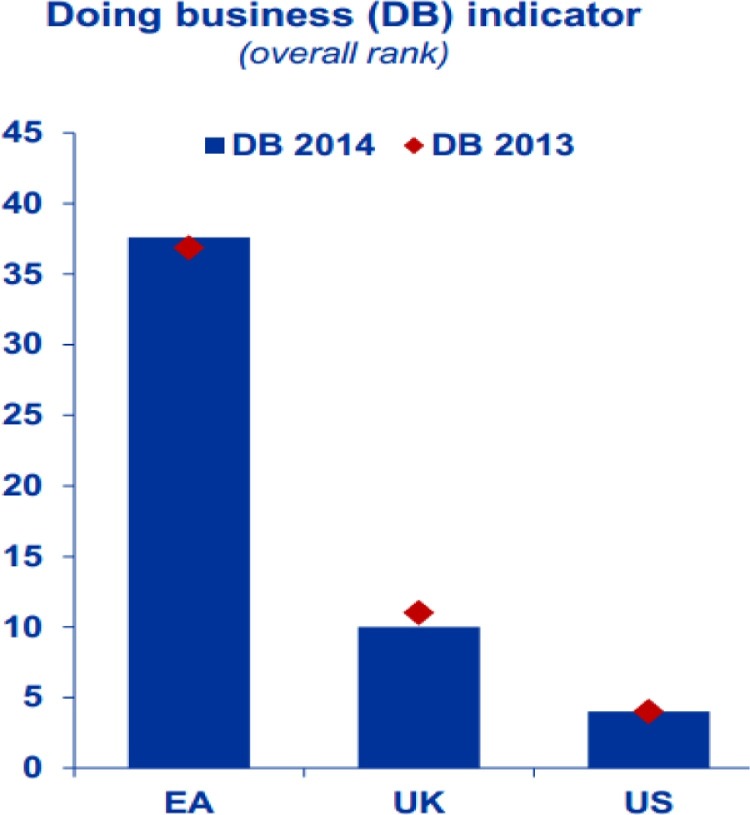

Growth was also discouraged in advanced nations by high taxes, overregulation and policy uncertainty – again, more so in Europe than in the United States and the United kingdom, as shown in Fig. 4 . To be noted is that the difference in growth between the United States and Europe is somewhat less on a per capita than in total because of the higher population growth in the United States than in Europe (Salvatore, 2017).

Fig. 4.

Doing business indicator.

Source: World Bank (2016).

6. Growth slowdown or recession in major emerging market economies

After their spectacular growth before the global financial crisis, growth also slowed in emerging market economies as a result of the crisis (Klein & Salvatore, 2013). The economic crisis in emerging market economies started as a result of contagion as the recession-afflicted advanced nations sharply cut imports from and the flow of investments to emerging markets during the global financial crisis. This was one reason for the decline in China's previous spectacular growth. While India's growth held up, the average annual percentage growth of real GDP in other large emerging countries (those in the G20 group) has been very slow (with exception of China, India and Indonesia – see Table 3 ).

Table 3.

Average annual percentage growth of real GDP in emerging countries in G20 in 2009–2019 and forecast for 2020–2021.

| Nation | Yearly aver. |

2020a | 2021a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 2010–2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |||

| China | 9.2 | 8.0 | 6.6 | 6.1 | 6.0 | 5.8 |

| India | 8.5 | 7.3 | 6.8 | 4.8 | 5.8 | 6.5 |

| Russia | −7.8 | 1.9 | 2.3 | 1.1 | 1.9 | 2.0 |

| Brazil | −0.1 | 0.4 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 2.2 | 2.3 |

| S. Africa | −1.5 | 2.0 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 1.0 |

| Korea | 0.7 | 3.5 | 2.7 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 2.3 |

| Indonesia | 4.7 | 5.5 | 5.2 | 5.0 | 5.1 | 5.2 |

| Mexico | −4.7 | 3.2 | 2.1 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 1.6 |

| Argentina | −5.9 | 2.4 | −2.5 | −3.1 | −1.3 | 1.4 |

| Turkey | −4.7 | 6.8 | 2.8 | 0.0 | 3.0 | 3.2 |

| S. Arabia | −2.1 | 4.0 | 2.4 | 0.2 | 1.9 | 2.2 |

Forecasts. Source: IMF, 2019, IMF, 2020a, IMF, 2020b.

The slowdown in China's growth rate from 2010 to 2017, however, was also the result of the effort to restructure its economy toward more internal demand and from a manufacturing to a service economy, rather than relying on continued export growth and on heavy domestic investments as in the past (the former because it was no longer sustainable and the latter because of the setting in of the “dreaded” diminishing returns). In the process, China's demand for primary commodity imports from other emerging markets (especially from Brazil and many African countries) also declined sharply. This caused an even greater growth slowdown in other emerging market economies than the decline resulting from the recession in advanced countries. Starting in 2018, China's growth slowed further as a result of the U.S.–China trade war (as discussed in Section 4). The growth forecast of China and other countries shown in Table 3 also does not take into consideration the reduction of growth of China and the rest of the world as a result of the coronavirus (COVID-19) that struck China in December 2019 and spread to many other nation in the beginning of 2020. Of course, if the coronavirus becomes a pandemic, as feared in February 2020 (The New York Times, 2020), there could be a very deep world recession in 2020.

As the demand for their primary exports of emerging market economies declined, their currencies sharply depreciated or were devalued, thus making the servicing of their previously accumulated heavy financial debt and dollar borrowings of over $6 trillion by 2018 unsustainable. Emerging market economies also experienced large net financial outflows, which exacerbated their economic problems even more. Brazil faced recession with a decline of real GDP of 3.5 in 2015 and 2016, Russia faced even more economic difficulties as a result also of the wars and the economic sanctions imposed on it, and Argentina and Turkey also faced an economic crisis.

The economic crisis in most emerging market economies would have been even deeper had they not been operating under some form of exchange rate flexibility or had not devalued their currencies (which cushioned to some extent their reduction in exports) and had they not also entered the crisis with more foreign exchange reserves accumulated during the commodity boom of the previous decade.

7. Could the U.S. trade war with China lead to a new global financial crisis?

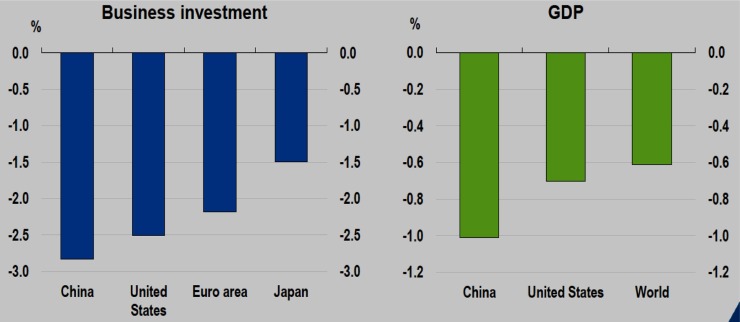

Fig. 5 shows (OECD, 2019) that the U.S.–China trade restriction imposed from July 2018 through August 2019 would reduce business investment after 2–3 years (with respect to the baseline) by about 2.8 percent in China, 2.5 percent in the United States, 2.3 percent in the Euro Area, and 1.5 percent in Japan. And it would reduce China's growth by about 1.0 percent, U.S. growth by 0.7 percent, and world growth by 0.6 percent. But if the U.S.–China trade war progresses and intensifies in 2020, the economic harm in terms of the reduction in world growth would be much higher, especially if other nations are also drawn into the trade war.

Fig. 5.

Impact of 2019 U.S.–China trade restriction: Difference from baseline after 2–3 years.

Source: OECD (2019).

The U.S.–China trade war is almost certain to also worsen the other economic weaknesses in the world economy today. These are (1) the excessive total indebtedness in the Chinese economy, now in excess of 275 percent of its GDP, (2) emerging markets’ total indebtedness in dollars, which now exceeds $6 trillion and in the face of an appreciating dollar, (3) the new financial bubble arising from nominal interest rates near zero in the United States, Britain and Canada and negative in Japan, the Euro Area (as well as in Denmark, Sweden and Switzerland), thus leading to inflated stock markets and also leading investors, in search for returns, to undertake “excessively” risky investments, and now (February 2020), we can add (4) the effect of the coronavirus or COVID-19 (for the result of other similar simulation exercises, see OECD (2016) and Salvatore and Campano (2018)).

Each of these weaknesses or dangers could, on its own, trigger a new global financial crisis and recession, but in the current trade-war situation each could actually lead to “a perfect storm” (i.e., a global financial crisis even deeper than the previous one) at a time when most advanced nations have fewer (and less effective) monetary and fiscal policies tools to deal with it.

In December 2019 the United States and China signed the Phase-One Agreement, which avoided a further escalation of their trade war, but with the United States leaving tariffs of 25 percent in place on nearly $370 billion of imports from China until a more extensive trade agreement is hopefully reached in 2020, this will continue to reduce international trade and growth. But even if such an agreement were reached, strong international trade controversies are likely to recur in the future, especially between the United States and China, unless the WTO were reformed and strengthened, and a truly rule-based international trade system were established.

8. Conclusions

After a decade from the end of the deepest global financial crisis and recession of the post-war period, world growth continues to be slow and even falling in most countries. There is now even the risk of the world drifting toward a new global financial crisis.

Two very important reasons for the slow recovery and growth in the United States and other advanced countries after the recent global financial crisis have been the decline in the growth of labor productivity and the labor force. Since these declines have been greater in Europe than in the United States, the former has grown slower than the latter. The reason the growth of labor productivity has been slower in Europe than in the United States was due mostly to the higher taxation and excessive regulations in Europe than in the United States.

Since his election, President Trump has reduced U.S. taxes and regulations and increased expenditure for infrastructures and the military. These policies did increase U.S. growth but only temporarily and led to much higher budget deficits. Accusing most nation of not engaging in fair trade, Trump also imposed higher tariffs on U.S. imports of steel, aluminum and other products on many countries and started a trade war with China, which reduced U.S. and world growth.

In the highly interdependent and globalized world of today, the slower growth of advanced nations and China reduced the growth of most other emerging market economies. Among the G20 market economies only China, India and Indonesia are growing rapidly (even though China's two digits growth rate prior to the global financial crisis has been cut in half).

The world is now facing the danger of another and possibly deeper financial crisis and recession if the U.S.–China trade war resumes. A crisis can also be triggered or amplified by the excessive indebtedness in the Chinese informal banking sector, by emerging markets’ total indebtedness in dollars, from the financial bubble arising from nominal interest rates near zero in the United States, Britain and Canada and negative in Japan, the Euro Area and other nations, and if the coronavirus turned into a pandemic.

References

- The Commerce Department United States in weakest recovery since 1949. The Wall Street Journal. 2016:A1. [Google Scholar]

- Conference Board . 2014. Total economy data base. Washington D.C. [Google Scholar]

- Congressional Budget Office . 2017. The budget and economic outlook. (January) [Google Scholar]

- Congressional Budget Office . 2017. Productivity and labor force growth as drivers of U.S. growth over time. [Google Scholar]

- European Central Bank . 2017. Annual report. [Google Scholar]

- IMF . 2019. World economic outlook. Washington, D.C. (October) [Google Scholar]

- IMF . 2020. World economic outlook. Washington, D.C. (January Update) [Google Scholar]

- IMF . 2020. Fiscal monitor. Washington, D.C. (April) [Google Scholar]

- Klein L., Salvatore D. From G-7 to G-20. Journal of Policy Modeling. 2013:416–424. [Google Scholar]

- OECD . 2016. OECD economic outlook. Paris (November) [Google Scholar]

- OECD . 2019. OECD economic outlook. Paris (November) [Google Scholar]

- Reinhart C.M., Rogof K. Princeton University Press; Princeton, N.J: 2009. This time is different. [Google Scholar]

- Salvatore D. Europe's structural and competitiveness problems and the Euro. The World Economy. 1998:189–205. [Google Scholar]

- Salvatore D. Globalization, comparative advantage and Europe's double competitive squeeze. Global Economy Journal. 2004:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Salvatore D. The U.S. challenge of European firms: Globalization, architecture, and perceived innovativeness. Inaugural Issue. European Journal of International Management. 2007:69–80. [Google Scholar]

- Salvatore D. Europe's growth crisis: When and how will it end? The World Economy. 2017:836–848. [Google Scholar]

- Salvatore D., Campano F. Simulating some of the administration's proposed trade policies. Journal of Policy Modeling. 2018:636–646. [Google Scholar]

- The New York Times . 2020. Surge in cases raises concern of a pandemic. (February 22), B1. [Google Scholar]

- White House Office of Trade and Manufacturing Policy . 2018. China's economic aggression. Washington D.C. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank . 2016. Doing business. Washington D.C. [Google Scholar]