COVID-19 confirmed fatalities in the United States (US) now lead the world [1]. One reason for the pandemics rapid spread is the virus has the ability to spread infection from asymptomatic individuals [2]. To counter this, we must have a better understanding of who is currently infected and needs isolating. Mass testing, with or without symptoms, offers a method of controlling the spread of infection and provides epidemiologists with valuable information about viral hot spots.

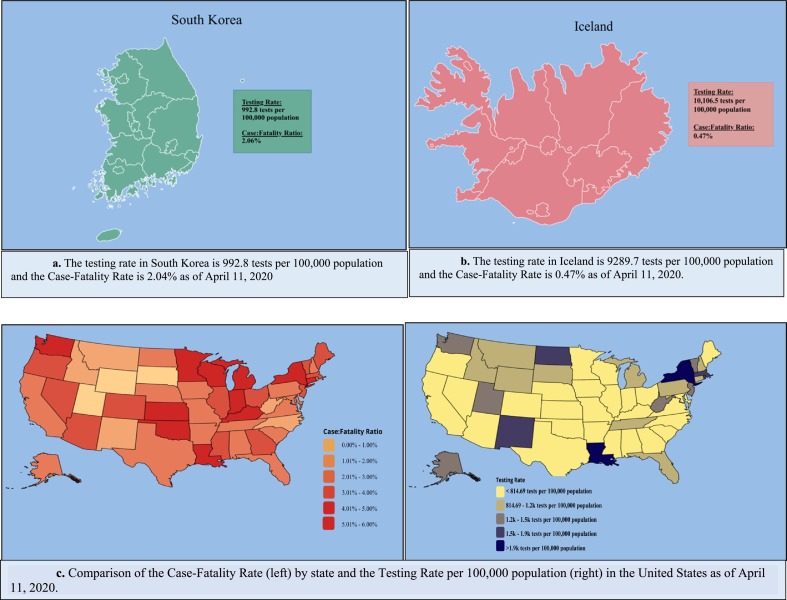

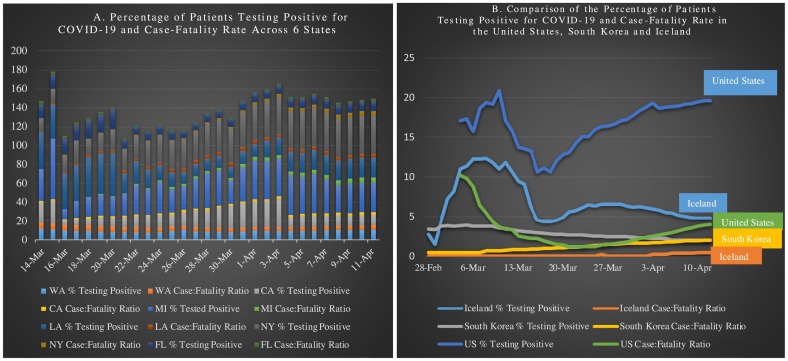

In Iceland, the focus centered on testing [3]. Iceland tested 14.8% of their population and reports a 0.4% fatality rate [4]. The low fatality rate observed is presumably due to random screening before their first confirmed case [3]. (Fig. 1, Fig. 2B ) Random sampling is effective for building an infection rate picture, allowing, healthcare officials to take action. However, major differences exist between the US, South Korea and Iceland that makes mass testing an impracticable solution for countries with large population densities [[5], [6], [7]]. Rapid testing of ~15% of the US population is less feasible and comes at an exponentially higher cost. Still, actions are being taken to expand the diagnostic supplies needed to improve overall testing in the US [8].

Fig. 1.

Comparison of the testing rate and case-fatality rate in South Korea, Iceland, and the United States.

Fig. 2.

The percentage of patients testing positive for COVID-19 and case-fatality rates across all US 4 regions (A) and comparison of the percentage of patients testing positive for COVID-19 and the case-fatality rate for the US, South Korea, and Iceland.

COVID-19 arrived to the US and South Korea on January 20th [1,9], Korea reports a fatality rate of 2% (April 10th, 2020), compared to 3.6% in the US [1]. The differences may be due to early testing, starting before their first outbreak [10]. The US did not start testing until a month after the first reported case [11,12]. The delay may play a role in the even higher fatality rate observed in Washington state (4.7%), as the outbreak in late February could have been detected via testing [12] (Fig. 1, Fig. 2B).

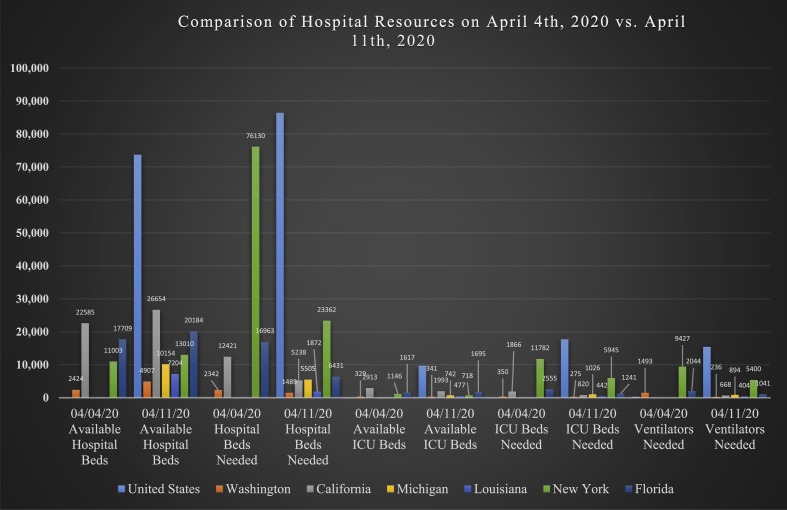

A delay in testing could be compounded by increased spread and skyrocketing healthcare demand. New York increased their testing capacity [13]. But as the percentage of individuals testing positive continues to increase (Fig. 2A), the case-fatality rate is increasing, suggesting that additional fatalities are persisting. This could be due in part to the lack of hospital resources experienced by New York and other states (Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of Hospital Resources among six States. Comparison of the number of available hospital beds, hospital beds needed, number of ICU beds, amount of ICU beds needed and number of ventilators needed on April 4th, 2020 vs. April 11th, 2020 in the United States*, Washington state, California, New York, Michigan*, and Louisiana*.

*Data for Hospital Resources on April 4th, 2020 not available for United States, Michigan, and Louisiana.

The importance of testing of the asymptomatic is implicated by analysis of infections in China, the report estimated that 86% of all infections were undocumented prior to travel restrictions on January 23rd, and responsible for half of all documented infections [14]. Additionally, the analysis found that undocumented cases were responsible for 79% of all cases [14].

Furthermore, it is important to retest those who tested negative while in quarantine. In a report from the Civil Protection Department in Iceland, 54% of patients were diagnosed with COVID-19 while they were in quarantine, meaning they did not test positive prior to this time [4]. Thus, it is important to follow up on these patients in order to ensure they are remaining in quarantine and not venturing out and potentiate the infection, re-exposure cycle.

If the immunity induced by COVID-19 infection is seasonal, rather than permanent, it likely will enter the circulation [15]. The virus can proliferate at any time and is likely to reemerge once social distancing measures have ceased [15]. Attempts to control the spread come with significant impacts on the economy. Invoking widespread testing for surveillance has the potential to determine changes in prevalence that warrant the start or end of distancing measures and success.

Now that the genomes of COVID-19 have been released, a molecular assay can be manufactured for the US that can determine who is infected [16]. Moreover, a potential drawback of the current Coronavirus tests is the time it takes to receive results. If this diagnostic device could bypass remote laboratories, many people could be tested and provide it more cost-effectively. Applying tele-medicine and GPS-enabled functionality to this device could track the infected patient who leaves isolation, alert people who may have been exposed. Improved early surveillance testing will be significant for those who are asymptomatic and at high risk for infection, particularly high risks groups [[17], [18], [19]]. In this way, a method of continuous targeted surveillance testing and identified hot spots is obtained, to track the spread of infection, apply interventions, and offer points of interception.

Prevalence of disease can be mitigated by hospital management of critical patients, however, it is evident the US is insufficiently resourced to withstand this burden. If we wait until case clusters arise to mandate distancing, the lag between these interventions and peak hospital resource use can lead to the regular overrunning of hospital resources, and unnecessary preventable deaths. It is crucial that we make active efforts of contact tracing, active ongoing surveillance and quarantine if we are to prevent further mass outbreaks. Let us learn from our current experiences of waiting until the pandemic is knocking at our front door to intervene and work together to build a new future that is more than a life spent in social distancing.

References

- 1.COVID-19 map. Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center; January 22, 2020. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html [Google Scholar]

- 2.Day M. Covid-19: identifying and isolating asymptomatic people helped eliminate virus in Italian village. BMJ. 2020 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1165. m 1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Government objectives and actions Iceland's response. https://www.covid.is/categories/icelands-response

- 4.COVID-19 in Iceland - statistics. Upplýsingar um Covid-19 á Íslandi. https://www.covid.is/data

- 5.Central Intelligence Agency; The world factbook: Iceland. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/resources/the-world-factbook/geos/ic.html

- 6.Central Intelligence Agency; The world factbook: South Korea. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/resources/the-world-factbook/geos/ks.html

- 7.Central Intelligence Agency; The world factbook: United States. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/resources/the-world-factbook/geos/us.html

- 8.COVID-19 data and surveillance. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; April 9, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/faq-surveillance.html [Google Scholar]

- 9.Novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) situation report – 1. World Health Organization; January 21, 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200121-sitrep-1-2019-ncov.pdf?sfvrsn=20a99c10_4 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wain R., Sleat D., Macon-Cooney B., Insall L. Institute for Global Change; April 6, 2020. Covid-19 testing in the UK: unpicking the lockdown.https://institute.global/tony-blair/covid-19-testing-uk-unpicking-lockdown [Google Scholar]

- 11.Revision to test instructions – CDC 2019 novel coronavirus (nCoV) real-time RT-PCR diagnostic panel. Department of Health & Human Services; February 26, 2020. https://www.aphl.org/Materials/Signed_CDC_Letter_to_PHLs-N3_Removal_Instructions_26Feb2020.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 12.Washington State Department of Health; Cumulative case and death counts. https://www.doh.wa.gov/Emergencies/Coronavirus

- 13.New York State Department of Health; 2020 press releases. https://health.ny.gov/press/releases/2020/index.htm

- 14.Li R., Pei S., Chen B. Substantial undocumented infection facilitates the rapid dissemination of novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV2) Science. 2020 doi: 10.1126/science.abb3221. eabb3221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kissler S.M., Tedijanto C., Goldstein E., Grad Y.H., Lipsitch M. Projecting the transmission dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 through the postpandemic period. Science. April 14, 2020. https://science.sciencemag.org/content/early/2020/04/14/science.abb5793.full [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Sah R., Rodriguez-Morales A.J., Jha R. Complete genome sequence of a 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) strain isolated in Nepal. Microbiology Resource Announcements. March 12, 2020. https://mra.asm.org/content/9/11/e00169-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Yancy C.W. COVID-19 and African Americans. JAMA. April 15, 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6548. Published online. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.People who are at higher risk for severe illness. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; April 15, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-at-higher-risk.html [Google Scholar]

- 19.Characteristics of health care personnel with COVID-19 - United States, February 12–April 9, 2020. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; April 17, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6915e6.htm?s_cid=mm6915e6_x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]