Abstract

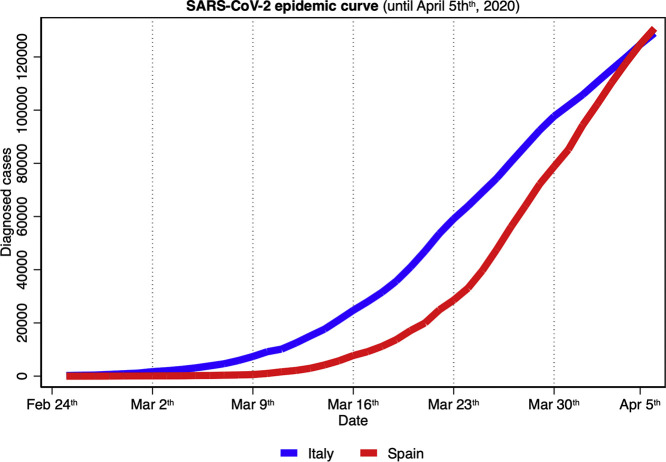

From the end of February, the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic in Spain has been following the footsteps of that in Italy very closely. We have analyzed the trends of incident cases, deaths, and intensive care unit admissions (ICU) in both countries before and after their respective national lockdowns using an interrupted time-series design. Data was analyzed with quasi-Poisson regression using an interaction model to estimate the change in trends. After the first lockdown, incidence trends were considerably reduced in both countries. However, although the slopes have been flattened for all outcomes, the trends kept rising. During the second lockdown, implementing more restrictive measures for mobility, it has been a change in the trend slopes for both countries in daily incident cases and ICUs. This improvement indicates that the efforts overtaken are being successful in flattening the epidemic curve, and reinforcing the belief that we must hold on.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, Lockdown, Interrupted time-series, Mortality, Intensive care unit admissions

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

The first confirmed cases of SARS-CoV-2 in Italy and Spain were identified a week apart in late February 2020 (Saglietto et al., 2020). Since then, Italy has become the third most affected country worldwide (128,948 cases, in April 5th) after the United States and has the highest number of deaths due to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic (15,887 deaths, in April 5th). Meanwhile, Spain is the second most affected in the number of diagnosed cases (130,759) and mortality (12,418) (Our World in Data, 2020).

Since March 8th, widespread lockdown measures have been in place in Italy. Specific measures restricting social contact were first introduced in the northern regions, where most cases had occurred, then extended to the whole country on March 10th. Furthermore, Italy tightened these measures extending the lockdown on March 21st: all businesses were closed, with the exception of those essential to the country's supply chains. Similarly, Spain imposed a lockdown on March 16th, with social distancing measures similar to those established in Italy. Two weeks later, on March 30th, Spain also implemented a more restrictive lockdown, aimed at reducing the mobility and non-essential industrial activity countrywide (Mitjà et al., 2020).

These restrictive measures have mainly been focused on flattening the epidemic curve. Most of the results reported daily by Governments, official agencies, and the media are aimed at describing cumulative epidemic data. Conversely, little attention has been paid to describe, quantify, and compare the lockdown effects within and between countries from an epidemiological point of view using incident data.

2. Methods

We collected data between February 24th and April 5th from the websites of the Italian and Spanish Ministries of Health (Dipartamento della Protezione Civille, 2020; Instituto de Salud Carlos III, 2020). We have analyzed the trends of the daily incident diagnosed cases, deaths, and intensive care units (ICU) admissions for SARS-CoV-2 in Italy and Spain before and during their respective national lockdowns, using an interrupted time-series design (Bernal et al., 2017). The data was analyzed with quasi-Poisson regression, using an interaction model to estimate the change in trends (Bernal et al., 2017). The data was analyzed using Stata, release 16 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, 2019).

3. Results

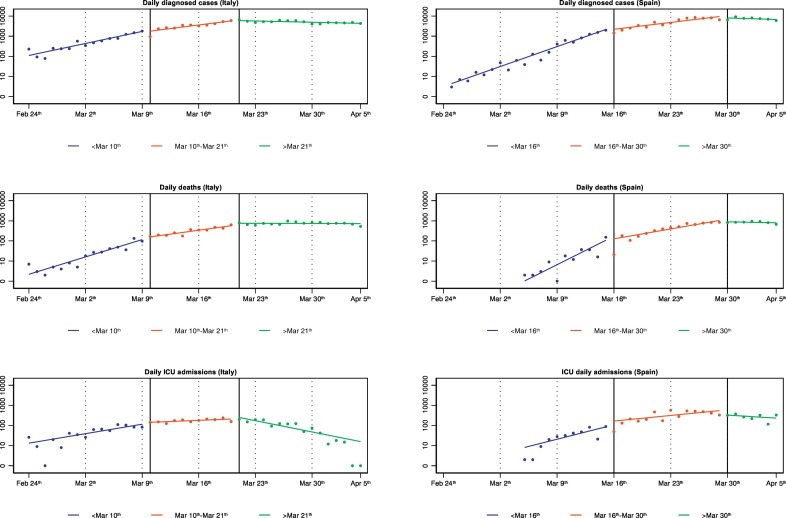

Fig. 1 shows the observed daily incident data and the estimated trend slopes for Italy and Spain since February 24th. Before the lockdown, the daily percent increase of all the incidence outcomes was higher in Spain (38.5% for diagnosed cases, 59.3% for deaths, and 26.5% for ICU admissions) than in Italy (21.6%, 32.8%, and 16.7%, respectively) (Table 1 ). During the first lockdown period, both countries show similar daily trends (12.5%, 13.7%, and 3.7% in Italy; and 11.9%, 17.6%, and 9.6% in Spain). Thus, during the first lockdown the daily increase in incident data was considerably reduced. In Italy, the diagnosed cases decreased by 42.1%, deaths by 58.2%, and ICU admissions by 77.8%. This reduction was even higher in Spain, where the diagnosed cases decreased by 69.1%, deaths by 77.8%, and ICU admissions by 66.8%. However, although the slopes have been flattened for all outcomes, the trends kept rising (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Trends and daily observed incident diagnosed cases, deaths and ICU admissions in Italy and Spain, between February 24th to April 5th.

Table 1.

Daily percent increase (%IR) of diagnosed cases, deaths and ICU admission in Italy and Spain, between February 24th and April 5th before and during their national lockdowns.

| Before lockdown |

First lockdowna |

Second lockdownb |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| %IR | (95% CI) | %IR | (95% CI) | %IR | (95% CI) | |

| Italy | ||||||

| Diagnosed cases | 21.6 | (16.2, 27.1) | 12.5 | (9.6, 15.5) | −2.0 | (−3.1, −0.9) |

| Deaths | 32.8 | (21.0, 44.6) | 13.7 | (10.1, 17.4) | −0.2 | (−1.5, 1.0) |

| ICU admissions | 16.7 | (10.3, 23.2) | 3.7 | (−0.6, 8.0) | −16.8 | (−20.2, −13.4) |

| Spain | ||||||

| Diagnosed cases | 38.5 | (27.0, 50.0) | 11.9 | (9.5, 14.3) | −2.7 | (−7.3, 1.9) |

| Deaths | 59.3 | (23.0, 95.2) | 17.6 | (14.4, 20.7) | −1.8 | (−5.0, 3.1) |

| ICU admissions | 26.5 | (0.4, 52.5) | 9.6 | (4.7, 14.7) | −5.6 | (−24.4, 6.9) |

First lockdown in Italy between March 10th and March 21th; and in Spain between March 16th and March 30th.

Second and more restrictive lockdown in Italy since March 21th; and in Spain since March 30th.

During the second and more restrictive lockdown, currently ongoing, both countries show some positive signs, indicating that trends may be changing (Fig. 1). Specifically, in Italy all outcomes start declining; diagnosed cases if −2.0%, daily deaths of −0.2%, and ICU admissions of −16.8%. Similarly, Spain also shows decline trends in daily diagnosed cases of −2.7%, deaths of −1.8%, and ICU of −5.6%.

4. Discussion

Lockdown, including restricted social contact and keeping open only those businesses essential to the country's supply chains, has had a beneficial effect in both countries. The trend slopes were considerably reduced for all the outcomes. However, this was not enough to change the rising trend of the epidemic. For this reason, more restrictive actions were suggested. The second lockdown, still ongoing, shows how the trends have changed, with a reduction of daily incident cases, deaths, and more significantly in ICUs. These are of similar magnitude in both countries, although Italy carries a week ahead of Spain. However, mortality still shows a small increase, probably because it follows incidence trends with a delay of 1–2 weeks. We should acknowledge that this figures could change during forthcoming weeks.

Analysis of trends using daily incident data may be a useful complement to more conventional approaches used to monitor the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic by testing and reporting changes overtime after a public health intervention (i.e., lockdown, confinement or quarantine). Interrupted time-series regression models are relatively easy to implement using readily available data by health authorities (Bernal et al., 2017). This is a descriptive analysis without predictive purposes. For an easy interpretation, and comparison of the effectiveness of lockdown measures between countries, a linear trend is assumed before and during the lockdown periods. The changes in the definition of diagnosed cases have not been taken into account, nor has the reduction in the susceptible population because of the lockdown. Therefore, the incident cases are modeled directly instead of the incidence rate, assuming that the entire population is at risk.

Timely indications for public health authorities and governments are essential to slow down the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic and relieve the pressure on overburdened health services. Although available data is still limited, and findings must be interpreted with caution, we believe that real-time detection of pattern changes are essential to evaluate the current measures of control and design future ones. In this sense, the positive signs already shown by the decreasing trend slopes after a more restrictive lockdown in Italy and Spain could indicate an optimistic and encouraging forecast for those countries that in late March also announced restrictive lockdown measures for flattening the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic curve (e.g., the United Kingdom on March 23th or Ireland on March 27th). These results show that the sacrifices that our society is making are gaining us valuable time, which is essential to get ready to face the future pressures that this epidemic will bring forth.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

To Milena Maule (Department of Medical Sciences, University of Turin) for her useful comments helping to improve the contents of the manuscript.

Editor: Damia Barcelo

References

- Bernal J.L., Cummins S., Gasparrini A. Interrupted time series regression for the evaluation of public health interventions: a tutorial. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017;46:348–355. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dipartamento della Protezione Civille 2020. COVID-19 Italia – Monitoraggio della situazione – (Accessed April 5th, 2020). Available from: http://opendatadpc.maps.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/b0c68bce2cce478eaac82fe38d4138b1.

- Instituto de Salud Carlos III 2020. Situación de COVID-19 en España. (Accessed April 5th, 2020). Available from: https://covid19.isciii.es/.

- Mitjà O., Arenas À., Rodó X., Tobias A., Brew J., Benlloch J.M. Experts' request to the Spanish government: move Spain towards complete lockdown. Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30753-4. (pii: S0140-6736(20)30753-4) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Our World in Data 2020. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) – Statistics and Research. Oxford Martin School, The University of Oxford, Global Change Data Lab. [Accessed April 5th, 2020]. Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus/.

- Saglietto A., D'Ascenzo F., Zoccai G.B., De Ferrari G.M. COVID-19 in Europe: the Italian lesson. Lancet. 2020;395(10230):1110–1111. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30690-5. (pii: S0140-6736(20)30690-5) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]