Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to examine exposure (i.e., seeing, following, posting) to body image content emphasizing a thin ideal on various social media platforms and probable eating disorder (ED) diagnoses, ED-related quality of life, and psychiatric comorbidities (i.e., depression, anxiety) among adolescents and young adult females recruited via social media who endorsed viewing and/or posting pro-ED online content. We also investigated health care utilization, treatment barriers, and opinions on harnessing technology for treatment.

Methods

Participants were 405 adolescent and young adult females engaged with pro-ED social media. We reported on study constructs for the sample as a whole, as well as on differences between age groups.

Results

84% of participants’ self-reported symptoms were consistent with a clinical/subclinical ED, and this was slightly more common among young adults. Participants endorsed reduced ED-related quality of life, as well as comorbid depression and anxiety. Among those with clinical/subclinical EDs, only 14% had received treatment. The most common treatment barriers were believing the problem was not serious enough and believing one should help themselves. The majority of participants approved of harnessing technology for treatment.

Conclusions

Results provide support for engagement with pro-ED online content serving as a potential indicator of ED symptoms and suggest promise for facilitating linkage from social media to technology-enhanced interventions.

Level of Evidence

Level V, cross-sectional descriptive study

Keywords: feeding and eating disorders, adolescent, young adult, social media, cross-sectional studies

Introduction

Eating disorders (EDs) are serious mental illnesses associated with high morbidity and mortality, clinical impairment, and comorbid psychopathology that typically begin in adolescence or young adulthood [1–4]. Furthermore, there is a wide treatment gap for EDs such that a majority of individuals (>80%) with these disorders never receive treatment [5–6]. There is increasing concern about online communities that promote ED behaviors and encourage a “thin ideal” and/or harmful weight loss/weight control practices [7–12], and these communities are widespread. A study of pro-ED online search terms found that queries for pro-ED terms occur frequently on Google (13 million searches annually) and generate harmful pro-ED online content [13]. Pro-ED messages online can be accessed easily by youth across the globe, and a 25-country European Kids Online survey found that 10% of children aged 9 to 16 had seen pro-ED sites online [14]. This phenomenon has also been observed on various social media platforms, including Twitter, Instagram, Pinterest, and YouTube [15–18], which adolescents and young adults use frequently.

Emerging studies signal ED-related psychopathology and associated risks among individuals who are socially networking online about pro-ED topics. Women recruited from websites, including social media pages, that featured “thinspiration” (i.e., images and text inspiring weight loss and an ED lifestyle) and pro-anorexia content expressed higher levels of disordered eating, lower levels of self-esteem, and higher levels of depression versus women recruited from websites that posted general information about anorexia nervosa (e.g., causes and consequences of anorexic behavior, recovery resources) [19]. Likewise, women posting “fitspiration” images (i.e., images designed to inspire viewers to eat healthily and exercise) on Instagram reported significantly more compulsive exercise and disordered eating behaviors versus a control group of women (i.e., women posting travel content) [20]. Finally, frequency of microblog viewing (i.e., social media pages on which “influencers” share small updates and content with followers) featuring nutritional and exercise-related content was significantly positively associated with disordered eating, while frequency of use of traditional blogs (i.e., a journal of ideas or a diary published online without a character limit) featuring this information was not [21]. Taken together, these findings signal ED-related psychopathology and impairment, as well as associated risks (e.g., psychiatric comorbidities) among individuals posting and/or viewing pro-ED content online.

The purpose of the current study was to examine exposure (i.e., seeing, following, posting) to body image content emphasizing a thin ideal on various social media platforms and probable ED diagnoses, ED-related quality of life, and psychiatric comorbidities (i.e., depression, anxiety) among adolescents and young adult females recruited via social media who endorsed viewing and/or posting pro-ED online content. More specifically, first, we describe participants’ engagement with pro-ED social media, including reporting on the platforms on which this content was most commonly seen, followed, and posted. Second, given that existing studies have identified ED-related symptomatology (but typically not probable diagnoses) among individuals engaged in pro-ED social networking, we hypothesized that a majority of participants would self-report clinically significant ED symptoms consistent with a clinical/subclinical ED diagnosis. We also reported on participants’ ED-related quality of life and psychiatric comorbidities (i.e., depression, anxiety). Third, bearing in mind the wide treatment gap for EDs and potential barriers to care that participants may experience, such as stigma and shame, denial of illness severity, practical barriers (e.g., cost), low motivation, negative attitudes about help-seeking, lack of encouragement, and lack of knowledge about resources, which are commonly reported in individuals with EDs [22], we also investigated participants’ health care utilization and barriers to treatment. Fourth, given the great potential for technology to address the treatment gap [5,23], opinions on the use of social media as an outreach tool to connect those in need to treatment, as well as generally on the potential for technology to be leveraged to increase access to treatment, were assessed. Finally, we note that we reported on these indices descriptively for the sample as a whole, as well as exploratorily on differences between adolescents (i.e., 15–17 year olds), when most EDs onset [2,4], and young adults (i.e., 18–25 year olds), in order to facilitate understanding of potential differences on the study constructs between these two developmentally distinct groups [24], both of which are high social media users [25–27], which may inform future directions. To our knowledge, this study is the first to comprehensively assess the extent to which the symptoms of individuals socially networking about EDs are consistent with a clinical or subclinical ED diagnosis.

Methods

Participants and recruitment

We recruited participants to take our cross-sectional online survey from Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, and Reddit in March through June of 2017. Using ads on Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter, we targeted English-speaking individuals in the United States who had demonstrated an interest in and/or followed accounts that were social networking about EDs or ED-related topics. Example keywords included: body image, body shape, dieting, female body shape, Eating Disorders Anonymous, National Eating Disorders Association, and recovering from an eating disorder. On Reddit, we posted about the study in two pro-ED related subreddits (i.e., topic-specific communities). These posts contained a brief overview of the online survey and a link to our study website.

The study website contained a link to take the online eligibility survey. Eligible participants were ≥15 years old, U.S. residents, and endorsed having posted on social media about eating/weight/body image, emphasizing that being thin is important or attractive, or followed social media accounts with this emphasis. We chose to use this rather broad definition of engagement with pro-ED social media content in order be able to assess the psychopathology (i.e., eating disorder, depression, anxiety), health care utilization, treatment barriers, and opinions on harnessing technology for treatment among a broad group of participants engaged with this potentially harmful content. After eligibility was established, participants read about the study risks and benefits and consented to participate online, and were then forwarded to the full online survey. Because participation only involved minimal risk, parental consent was waived for participants 15–17 years old. Qualtrics survey software (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) was used to create and distribute the survey online and was accessible via computer or mobile device. Participants were compensated with a $10 Amazon.com gift card after survey completion. This study was reviewed and approved by the Washington University Institutional Review Board.

A total of 1998 participants accessed our eligibility survey. Of the 1062 participants who were eligible, 1055 consented to participate. In addition to using Captcha to prevent machine responses and a Qualtrics feature to help prevent duplicate responses, we also cleaned the data using several steps to minimize low-quality survey responses [28–30]. We removed 334 participants who only progressed through less than half of the survey, 68 participants who took the survey in less than 8 minutes (lowest 10th percentile of survey time), 37 responses that appeared to be duplicates, and 18 suspicious responses (e.g., inconsistent or illogical response patterns). After removing these, 598 participants remained in the data (median survey completion time 22 minutes, IQR 17–30 minutes).1 Given high social media use among adolescents and young adult individuals in particular [25–27] and our interest in comparing these groups on the study variables, we focused the current study on participants ages 15–25 years old. We also focused our analysis on female participants, excluding non-female participants, given there were low numbers of male (n=20) and transgender/genderqueer (n=52) participants and these groups tend to experience EDs differently than females (e.g., EDs in males often present as muscle dysmorphia [31]; EDs in transgender individuals may be associated with them attempting to make their bodies appear more feminine/masculine [32–24]). This left a total sample size of 405 adolescent and young adult female participants for analysis.

Survey measures

Exposure to thin ideal content on social media was assessed with three items. Two items assessed how often in the past month participants had seen a social media post from a peer or posted on social media about their own thoughts about eating/weight/body image that emphasized being thin is important or attractive. Platforms that were separately queried included Twitter, Facebook, Snapchat, Instagram, Tumblr, YouTube, and Reddit. Response options were: never, once, 2–5 times, 6–10 times, and more than 10 times. For purposes of quantifying the number of times the content was seen or posted across all social media platforms, responses were converted to numeric taking the number value or midpoint of categories (i.e., never=0, once=1, 2–5 times=3.5, 6–10 times=8, more than 10 times=11) and summing across all social media platforms. In addition participants were asked whether they followed accounts on each social media platform that posted about this type of content (response options were yes/no).

ED risk and DSM-5 diagnostic categories (i.e., not at risk, at risk for an eating disorder, possible anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN), binge eating disorder (BED), subclinical BN, subclinical BED, purging disorder, unspecified feeding or eating disorder (UFED) were assessed using the Stanford-Washington Eating Disorder Screen (SWED), a brief online self-report tool that assesses ED pathology and risk with good sensitivity and specificity for most diagnoses [35]. Health-related quality of life associated with disordered eating was assessed with the Eating Disorders Quality of Life instrument (EDQOL), a 25-item scale assessing the frequency with which participants experienced specific ED-related impairments [36]. The EDQOL contains four subscales (i.e., psychological, physical/cognitive, financial, and work/school). Both subscale and total scores range from 0 to 4, with higher scores indicating worse QOL. The EDQOL has excellent psychometric properties [36] and has been used among adolescents [37]. Internal consistency within our data was good to excellent (Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for overall scale was 0.94, for subscales: 0.94 for psychological subscale, 0.90 for physical/cognitive subscale, 0.79 for financial subscale, and 0.85 for work/school subscale).

Psychological comorbidities, including depression and anxiety, were assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), a nine-item instrument used to screen for depression severity based on the DSM-IV depression diagnostic criteria [38], and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7) scale, which identifies probable GAD and assesses severity of symptoms [39]. Both scales have good psychometric properties and have been validated in both adults and adolescents [38, 40–42]. Internal consistency was excellent for both scales within our data (Cronbach’s alphas of 0.91 and 0.92 for PHQ-9 and GAD-7, respectively). Scores on the PHQ-9 and the GAD-7 range from 0 to 27 and from 0 to 21, respectively. We used threshold scores to determine probable major depression (PHQ-9 threshold score ≥10, sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 88%) [38] and anxiety (GAD-7 threshold score ≥10, sensitivity of 89% and specificity of 82%) [40]. In addition, we also examined scores as continuous variables to explore severity of depression and anxiety.

Utilization of health care services was assessed with an item that queried whether participants had received any treatment for eating related problems in the past six months as well as in their lifetime. Among those who did not receive treatment in the past six months, barriers to treatment were assessed using 18 items modified from [43]. 5-point Likert scale responses ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree were dichotomized (agree/strongly agree versus all others) to report the percent that agreed with each statement.

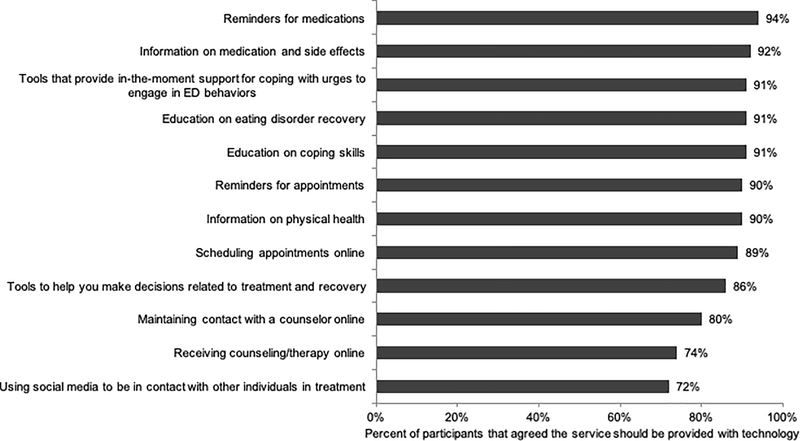

Participants’ opinions of leveraging social media for research recruitment and linkage to treatment was assessed with a) an item that queried whether the participant approved of researchers finding people on social media that might be eligible for their studies (dichotomized as approve/strongly approve versus all others), and b) an item that measured participants’ agreement with whether social media sites could be used to connect people to treatment (if confidentiality could be ensured) (dichotomized as agree/strongly agree versus all others). Participants’ opinions about whether several types of services related to EDs could be provided with technology (e.g., online, apps) were also assessed (and dichotomized as agree/strongly agree versus all others). Finally, participants were queried about their interest in trying an evidence-based mobile mental health program for EDs that included coaching (responses dichotomized as probably/definitely interested versus all others).

The survey also inquired about participants’ demographic characteristics, including age, gender, race/ethnicity, enrollment in school, employment status, and annual household income.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the demographic, social media use, and diagnostic characteristics of our sample. Adolescents (15–17 years) and young adults (18–25 years) were compared using Pearson Chi-square tests for categorical variables (e.g., ED diagnoses, engagement in treatment) and Mann Whitney U tests for continuous variables (e.g., EDQOL scores, depression scores, anxiety scores), as these variables were not normally distributed (all Shapiro-Wilk tests p<0.001). Given that the majority of analyses were considered exploratory in nature, no adjustments for multiple testing were made, as is common practice in exploratory studies [44–46]. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 for Windows (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). All analyses were complete case analyses, assuming all missing data were at random.

Results

Demographics

Demographic characteristics for our 405 adolescent and young adult female participants (both overall and by age group) can be found in Table 1. The sample was relatively evenly split by age group (51% 15–17 years old, 49% 18–25 years old). The large majority was non-Hispanic White (65%). As expected, more 15–17 year olds were students (98%) than 18–25 year olds (65%) (X2 df 1 =72.8, p<0.001) and more 18–25 year olds were employed (69%) than 15–17 year olds (27%) (X2 df 1 =72.0, p<0.001). The social media platform from which participants were recruited differed by age group (X2 df 3 =183.9, p<0.001); the greatest proportion of our adolescent sample was recruited from Instagram (76%), while nearly half (46%) of the young adult sample was recruited from Reddit.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of female participants, including by age group (N = 405 unless otherwise noted due to missing data)

| Overall (N=405) | By age group |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Age 15–17 yrs (n=207) | Age 18–25 yrs (n=198) | p | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Race/Ethnicity (n=404) | 0.349 | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 264 (65) | 127 (61) | 137 (69) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 24 (6) | 16 (8) | 8 (4) | |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 28 (7) | 15 (7) | 13 (7) | |

| Non-Hispanic Other Race | 33 (8) | 17 (8) | 16 (8) | |

| Hispanic | 55 (14) | 32 (15) | 23 (12) | |

| Enrolled as a student | <0.001 | |||

| No | 75 (19) | 5 (2) | 70 (35) | |

| Yes | 330 (81) | 202 (98) | 128 (65) | |

| Employed | <0.001 | |||

| No | 212 (52) | 151 (73) | 61 (31) | |

| Yes (part-time or full-time) | 193 (48) | 56 (27) | 137 (69) | |

| Annual household income (n=391) | <0.001 | |||

| <$25,000 | 131 (34) | 45 (23) | 86 (44) | |

| $25,000 to $49,999 | 88 (23) | 53 (27) | 35 (18) | |

| $50,000 to $74,999 | 66 (17) | 32 (16) | 34 (17) | |

| ≥$75,000 | 106 (27) | 65 (33) | 41 (21) | |

| Recruited from... | <0.001 | |||

| 182 (45) | 158 (76) | 24 (12) | ||

| 100 (25) | 9 (4) | 91 (46) | ||

| 73 (18) | 19 (9) | 54 (27) | ||

| 50 (12) | 21 (10) | 29 (15) | ||

Exposure to body image content emphasizing a thin ideal on social media

Nearly all participants (96%) reported seeing their peers post on social media about eating/weight/body image emphasizing that being thin is important or attractive in the past month (98% of young adults, 94% of adolescents, X2 df 1 =5.2, p=0.023). Approximately 83% of participants reported seeing this content at least 10 times in the past month (89% of young adults, 78% of adolescents, X2 df 1 =8.3, p=0.004). Furthermore, 96% of participants reported following at least one social media account that posted about this type of content (97% of young adults, 96% of adolescents, X2 df 1 =0.5, p=0.483). The median number of social media platforms on which they followed such accounts was 3 (IQR 2 to 4); this did not differ by age group (p=0.861).

Approximately 72% of participants reported posting on social media in the past month about this type of content (77% of young adults, 67% of adolescents, X2 df 1 =5.2, p=0.023). Approximately 31% of participants posted at least 10 times in the past month (35% of young adults, 28% of adolescents, X2 df 1 =2.9, p=0.090).

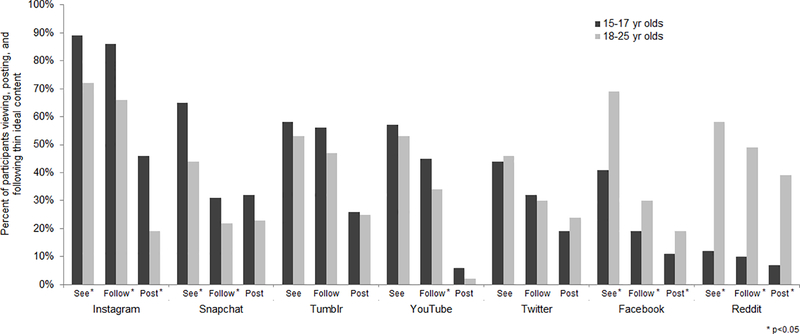

The most common social media platforms on which participants reported seeing, following, and posting thin ideal content are shown in Figure 1. Overall, participants most commonly reported seeing, following, and posting content emphasizing a thin body ideal on Instagram (one of our recruitment platforms), and adolescents were more likely than young adults to report this (saw content: 15–17 yr olds 89%, 18–25 yr olds 72%, X2 df 1 =18.1, p<0.001; followed content: 15–17 yr olds 86%, 18–25 yr olds 66%, X2 df 1 =22.0, p<0.001; posted content: 15–17 yr olds 46%, 18–25 yr olds 19%, X2 df 1 =32.1, p<0.001). Adolescents also commonly reported seeing and following such content on Snapchat (65% saw content, 31% followed content), more so than young adults (44% saw content, 22% followed content) (X2 df 1 =19.1, p<0.001, X2 df 1 =4.8, p=0.028). On the other hand, young adults more commonly reported seeing, following, and posting this content on Reddit (another of our main recruitment platforms) than adolescents (saw content: 15–17 yr olds 12%, 18–25 yr olds 58%, X2 df 1 =89.7, p<0.001; followed content: 15–17 yr olds 10%, 18–25 yr olds 49%, X2 df 1 =69.4, p<0.001; posted content: 15–17 yr olds 7%, 18–25 yr olds 39%, X2 df 1 =55.5, p<0.001). Compared to adolescents, young adults also more commonly reported seeing, following, and posting this content on Facebook (saw content: 15–17 yr olds 41%, 18–25 yr olds 69%, X2 df 1 =31.6, p<0.001; followed content: 15–17 yr olds 19%, 18–25 yr olds 30%, X2 df 1 =6.9, p=0.008; posted content: 15–17 yr olds 11%, 18–25 yr olds 19%, X2 df 1 =4.9, p=0.027). Participants also commonly reported seeing and following this content on Twitter (45% saw peers post, 31% followed accounts), Tumblr (55% saw peers post, 52% followed accounts), and YouTube (56% saw peers post, 40% followed accounts), but the only significant difference by age group was following content on YouTube (45% of adolescents, 34% of young adults, X2 df 1 =5.6, p=0.018).

Figure 1.

Exposure to thin ideal content on social media platforms (saw content, followed content, and posted content) by age group

ED diagnoses, quality of life, and psychiatric comorbidities (i.e., depression, anxiety)

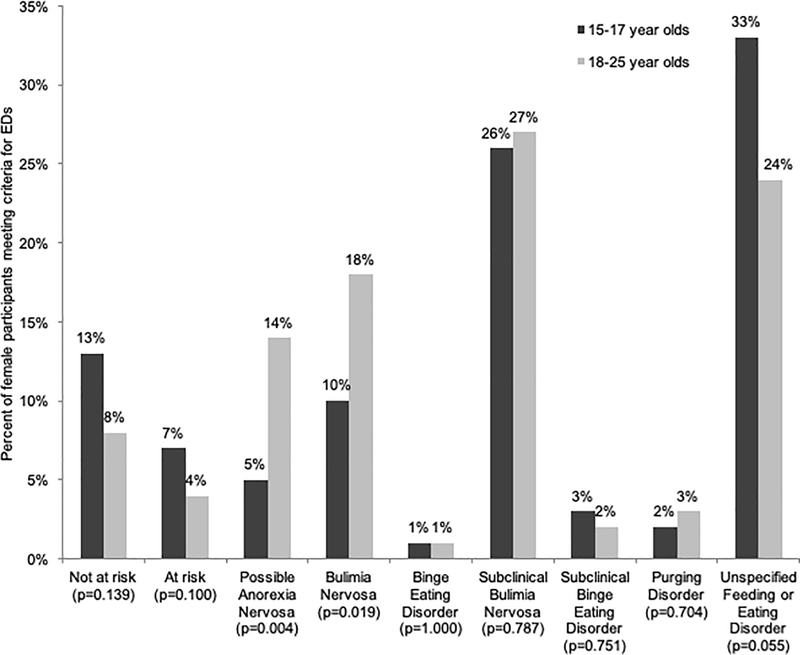

The possible ED diagnoses (as determined by the SWED) for both age groups are presented in Figure 2. Most participants (84%) met the criteria for a clinical or subclinical eating disorder, and this was slightly more common among young adults (88% of 18–25 year olds) than adolescents (80% of 15–17 year olds, X2 df 1 =5.1, p=0.024). The most common diagnoses were subclinical BN (26% of 15–17 year olds, 27% of 18–25 year olds; X2 df 1 =0.07, p=0.787) and UFED (33% of 15–17 year olds and 24% of 18–25 year olds; X2 df 1 =3.7, p=0.055). Young adults were more likely to screen positive for possible AN (14% vs 5%, X2 df 1 =8.2, p=0.004) or BN (18% vs 10%, X2 df 1 =5.5, p=0.019) versus adolescents. There were no differences in the prevalence of other ED diagnoses by age group.

Figure 2.

Eating disorder risk and diagnostic categories in adolescents (15–17 year olds) and young adults (18–25 year olds)

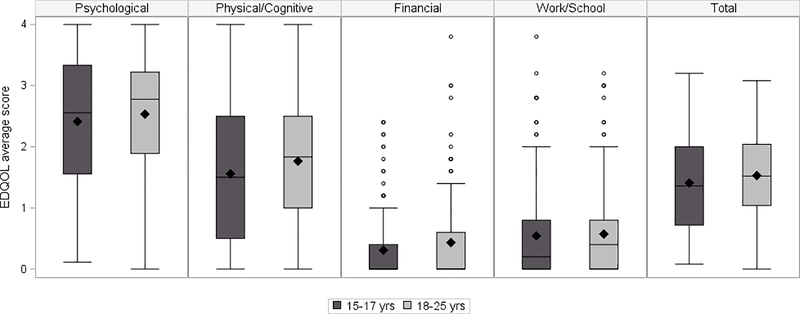

EDQOL scores also differed by age group (see Figure 3). While total EDQOL scores did not differ across groups (p=0.099), results suggested significantly worse physical/cognitive-specific EDQOL for young adults (median 1.83, IQR 1.00 to 2.50; p=0.0499) compared to adolescents (median 1.50, IQR 0.50 to 2.50; p=0.0499). Psychological-specific EDQOL scores were highest, indicating worse quality of life in this area, relative to the other subscales (medians 2.55 for adolescents and 2.78 for young adults) but did not differ significantly by age group. Financial-specific EDQOL scores were low but the distribution was slightly higher for young adults (young adults median 0.00, IQR 0.00 to 0.60; adolescents median 0.00, IQR 0.00 to 0.40; p=0.036).

Figure 3.

EDQOL scores by age group

Regarding psychological comorbidities, 71% of participants reported symptoms consistent with major depression. In addition, 65% of participants reported symptoms consistent with moderate to severe anxiety. Depression was more common among adolescents (76%) than young adults (66%; X2 df 1 =4.6, p=0.032), but the distribution of depression severity scores did not differ between groups (adolescents median 15, IQR 10 to 21; young adults median 15, IQR 8 to 20; p=0.343). The prevalence of anxiety did not differ significantly between the two age groups (adolescents 67%, young adults 62%, X2 df 1 =1.1, p=0.290), and neither did anxiety severity scores (adolescents median 13, IQR 8 to 17; young adults median 12, IQR 6 to 18; p=0.499).

Health care utilization and barriers to treatment

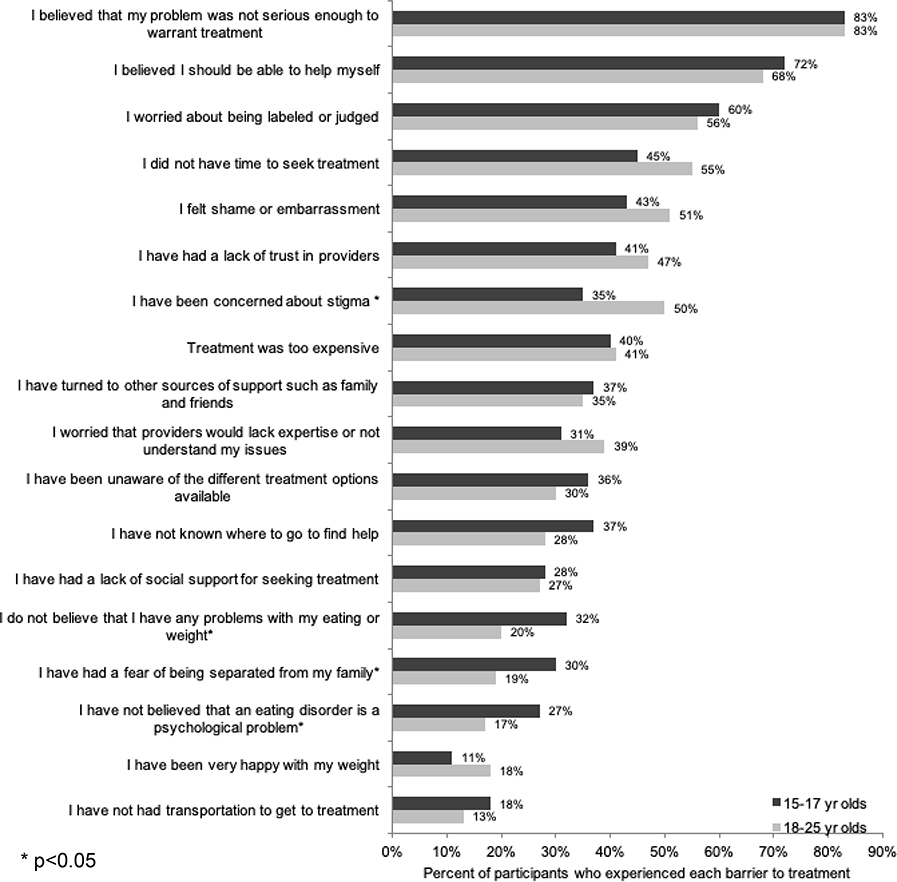

Among those with clinical or subclinical ED diagnoses (n=341), very few had received treatment for any eating related problems in the past six months (14% overall; 14% of 15–17 yr olds, 14% of 18–25 yr olds), and 22% of young adults and 13% of adolescents had received treatment at some point earlier in their lifetime (13%) (X2 df 2 =5.6, p=0.006). Among those with clinical/subclinical diagnoses who did not receive treatment in the past six months (n = 292), Figure 4 presents barriers to treatment by age group. The median number of barriers was 7 (IQR 4 to 9), and this did not differ significantly by age group. The most common reason for not seeking treatment was the belief that their problem was not serious enough to need treatment (>80% for each age group), followed by the belief that they should be able to help themselves (around 70% for each group). Participants also commonly reported worry about being labeled/judged (>50% for each group). Young adults were more likely than adolescents to express concerns about stigma (50% vs 35%, X2 df 1 =6.4, p=0.012). Adolescents were more likely than young adults to believe that they didn’t have a problem with an ED (32% vs 20%, X2 df 1 =5.3, p=0.021), that an ED is not a psychological problem (27% vs 17%, X2 df 1 =4.4, p=0.037), and to fear being separated from their family (30% vs 19%, X2 df 1 =4.9, p=0.028).

Figure 4.

Barriers to seeking treatment by age, among individuals screening positive for a clinical or subclinical eating disorder not engaged in treatment

Leveraging technology to facilitate access to treatment

The majority of participants approved of recruiting individuals on social media for research (80%) and agreed that social media could be used to facilitate linkage into treatment (83%). Participants overwhelmingly agreed that many services related to EDs should be provided with technology (Figure 5), ranging from medication information/reminders and in-the-moment support (>90%) to using social media to contact others in treatment and receive online counseling (>70%). Of these digital therapy interests, only the belief that technology should be leveraged to provide in-the-moment support for coping differed by age group, but still remained high in both groups (15–17 yr olds 95%, 18–25 yr olds 88%, X2 df 1 =4.9, p=0.027). In addition, 84% of participants indicated interest in trying an evidence-based mobile mental health program that includes a human component (i.e., e-coaching).

Figure 5.

Beliefs that specific services related to eating disorders should be provided with technology, among both age groups combined

Discussion

The purpose of the current study was to examine exposure (i.e., seeing, following, posting) to body image content emphasizing a thin ideal on various social media platforms and probable ED diagnoses, ED-related quality of life, and psychiatric comorbidities (i.e., depression, anxiety) among adolescents and young adult females recruited via social media who endorsed viewing and/or posting pro-ED online content. First, results shed light on the social media platforms on which participants had the most exposure to this content. Exposure to this content on Instagram and Snapchat was most common for adolescents, while Facebook and Reddit, as well as Instagram, emerged as the key sources of exposure for young adults.

Next, our findings are significant for shedding new light on the level of ED psychopathology among individuals socially networking online about EDs. While existing research has examined ED-associated risks among individuals who post and/or view pro-ED content online [19–21], our study is the first known of its kind to comprehensively assess the extent to which these individuals’ symptoms are consistent with a clinical or subclinical ED diagnosis. Thus, our findings reveal a more accurate picture of the ED-related psychopathology among those social networking about EDs, defined broadly. Consistent with our hypothesis, results indicated that the vast majority of participants’ self-reported symptoms were significant enough to warrant a clinical or subclinical ED diagnosis (84%), with the most common diagnoses being subclinical BN and UFED. These data provide strong support for engagement with pro-ED online content serving as a potential indicator of symptoms consistent with a clinical/subclinical ED. Of additional concern, most participants endorsed reduced ED-specific health-related quality of life as well as comorbid depression and anxiety. It is notable that the ED-specific health-related quality of life scores of participants in the current study were similar to those reported among females with EDs (determined by diagnostic interviews) in validity tests of the EDQOL [36]. Furthermore, rates of depression and anxiety are on par with or even on the high side of the range of reported prevalence for these comorbidities among individuals with EDs [47–51]. It is possible that the high rates of depression and anxiety observed in the current sample may be influenced by the link between social media use and these psychiatric disorders [52–53].

Despite the high level of ED symptomatology exhibited by participants in the current study, most had never received treatment for their ED. Our findings corroborate existing data that indicate most individuals with EDs (>80%) do not receive treatment [5]. Participants also endorsed major barriers to treatment that parallel with those identified in previous research, including lack of problem recognition and worries about being judged/labeled [6, 22]. Both young adults and teens endorsed having a lack of time for treatment and concerns about stigma, though these barriers were significantly more likely among young adults versus teens. Of concern, both young adults and teens reported a having a lack of trust in providers and cost of treatment as relatively common barriers to treatment.

On the whole, participants felt strongly that social media could be used for study recruitment and as a way to link people with treatment. They also could see the potential of using technology to provide ED-related treatment services. As the healthcare industry continues to see an uptick in the use of digital therapeutics [54], the acceptance of this form of technology among participants is promising. Existing Internet- and app-based interventions have already demonstrated initial efficacy for decreasing ED symptoms [55]. Based on results of the current study, there is great potential for linking individuals engaged in pro-ED social networking to such interventions, who, as demonstrated by the current study, generally meet criteria for an ED and exhibit reduced quality of life and elevated psychiatric comorbidities.

Strengths of this study include the use of a large sample, which was relatively evenly split between adolescents and young adults. This is also the first study to examine the extent to which the symptoms of individuals socially networking online about EDs are consistent with clinical/subclinical ED diagnoses and to compare barriers to care for EDs across adolescents and young adults. We also note that very little prior work has examined barriers to care for EDs in adolescents, and thus, the current study adds to the literature in this way as well. However, findings should be interpreted in the context of limitations, including information regarding possible ED diagnoses being based on self-report questionnaires rather than diagnostic interviews, the use of items developed specifically for this study where existing measures were not available (e.g., items assessing pro-ED social media usage, items assessing interest in use of technology for facilitating linkage to treatment), and the fact that we were not able to track why individuals may have been targeted with ads for our study. Additionally, participants who did not endorse having posted pro-ED content or following such accounts were screened out, and thus there was no control group used in this study. As a primarily exploratory study, our findings require replication in future work. An additional key future direction includes testing the feasibility of linking individuals from social media, particularly Instagram, Snapchat, Facebook, and Reddit, to ED intervention options, including a technology-enhanced treatment option. Such an approach would facilitate immediate access to treatment and address numerous barriers to care that participants reported experiencing, including stigma, lack of time, and cost.

Regarding clinical implications, beyond the work that needs to be done connecting individuals from social media to accessible intervention options, these findings highlight the association between social media and disordered eating. However, one study suggested that only 20% of therapists had asked patients with eating disorders about the impact of Facebook on their symptoms [56]. Moving forward, therapists are encouraged to carefully review clients’ social media use and its potential impact on symptomatology, incorporating this as a key treatment target when indicated [57]. In addition, this work is suggestive of important policy implications, including what social media sites can do to discourage this content. For example, for certain pro-ED hashtags, Instagram will either return no results or present the user with a warning message and encourage them to seek help [58]. However, other tags (e.g., related terms, deliberate misspellings) are now emerging as replacements [58]. Recently, due to a push by actress Jameela Jamil, Instagram has also rolled out a new policy prohibiting posts promoting weight loss products and cosmetic procedures to users under the age of 18 [59]. Moving forward, in order to maximize the likelihood of change, wide-ranging stakeholders, including mental health clinicians and researchers, as well as those with lived experience [60], should continue to come together to work with social media sites to bring positive changes to the platforms, in order to create a safe environment for all users.

Emerging studies warn that ED-related psychopathology, symptomatology, and associated risks exist among individuals who are socially networking online about pro-ED topics [19–21]. Utilizing various social media platforms (Facebook, Instagram, Reddit, and Twitter), we recruited and analyzed a sample of adolescents and young adult females who were engaging in ED-related social networking and found concerning trends that include probable clinical/subclinical ED diagnoses for a majority of participants, poor ED-related quality of life, and high levels of psychiatric comorbidities. Perhaps of greatest concern is that most of these individuals were not engaged in treatment despite their self-reported EDs and associated negative consequences. However, it is encouraging that participants expressed interest in technology-enhanced ED treatment which signals a promising pathway to support ED recovery.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health [grant numbers R21 MH112331 and K08 MH120341].

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

We compared survey completers (n = 598) to survey non-completers (n = 334) on items appearing early in the survey, including 1) percent of individuals reporting use of specific social media platforms several times a day; 2) average minutes spent on specific social media platforms when logging in; 3) percent of individuals reporting seeing peers posting thin ideal content on specific social media platforms in the past month; and 4) percent of individuals reporting posting thin ideal content on specific social media platforms in the past month. For these items, we queried the social media platforms of Twitter, Facebook, Snapchat, Instagram, Tumblr, YouTube, and Reddit. Groups generally did not differ with just a few exceptions to this pattern of findings. More non-completers reported using Instagram several times a day relative to completers (p=0.003), whereas more completers reported using Reddit several times a day relative to non-completers (p<0.001). Completers reported using Snapchat more minutes per day on average (M=30, SD=104) relative to non-completers (M=24, SD=37) (p=0.007). More completers reported seeing thin ideal content on Tumbler (p=0.037) and Reddit (p<0.001) relative to non-completers, whereas more non-completers reported seeing thin ideal content on Instagram relative to completers (p=0.020). Finally, more completers reported posting thin ideal content on Reddit relative to non-completers (p=0.002). Overall, completers and non-completers reported similar social media use patterns, with just a few minor differences, as noted above.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- 1.Klump KL, Bulik CM, Kaye WH, Treasure J, Tyson E (2009). Academy for eating disorders position paper: eating disorders are serious mental illnesses. Int J Eat Disord 42:97–103. 10.1002/eat.20589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Micali N, Hagberg KW, Petersen I, Treasure JL (2013). The incidence of eating disorders in the UK in 2000–2009: findings from the General Practice Research Database. BMJ Open 3:e002646 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stice E, Marti CN, Rohde P (2013). Prevalence, incidence, impairment, and course of the proposed DSM-5 eating disorder diagnoses in an 8-year prospective community study of young women. J Abnorm Psychol 122:445–457. 10.1037/a0030679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Volpe U, Tortorella A, Manchia M, Monteleone AM, Albert U, Monteleone P (2016). Eating disorders: What age at onset? Psychiatry Res 238:225–227. 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.02.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kazdin AE, Fitzsimmons-Craft EE, Wilfley DE (2017). Addressing critical gaps in the treatment of eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord 50:170–189. 10.1002/eat.22670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eisenberg D, Nicklett EJ, Roeder K, Kirz NE (2011). Eating disorder symptoms among college students: Prevalence, persistence, correlates, and treatment-seeking. J Am Coll Health 59:700–707. 10.1080/07448481.2010.546461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borzekowski DL, Schenk S, Wilson JL, Peebles R (2010). e-Ana and e-Mia: A content analysis of pro-eating disorder web sites. Am J Public Health 100:1526–1534. 10.2105/ajph.2009.172700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Custers K, Van den Bulck J (2009). Viewership of pro-anorexia websites in seventh, ninth and eleventh graders. Eur Eat Disord Rev 17:214–219. 10.1002/erv.910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harper K, Sperry S, Thompson JK (2008). Viewership of pro-eating disorder websites: association with body image and eating disturbances. Int J Eat Disord 41:92–95. 10.1002/eat.20408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Juarez L, Soto E, Pritchard ME (2012). Drive for muscularity and drive for thinness: the impact of pro-anorexia websites. Eat Disord 20:99–112. 10.1080/10640266.2012.653944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peebles R, Wilson JL, Litt IF, Hardy KK, Lock JD, Mann JR, Borzekowski DL (2012). Disordered eating in a digital age: eating behaviors, health, and quality of life in users of websites with pro-eating disorder content. JMIR 14:e148 10.2196/jmir.2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodgers RF, Skowron S, Chabrol H (2012). Disordered eating and group membership among members of a pro-anorexic online community. Eur Eat Disord Rev 20(1):9–12. 10.1002/erv.1096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lewis SP, Arbuthnott AE (2012). Searching for thinspiration: The nature of Internet searches for pro-eating disorder websites. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 15(4):200–204. 10.1089/cyber.2011.0453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Livingstone S, Haddon L, Görzig A, Ólafsson K (2010). Risks and safety on the Internet: the perspective of European children: key findings from the EU Kids Online survey of 9–16 year olds and their parents in 25 countries. EU Kids Online. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghaznavi J, Taylor LD (2015). Bones, body parts, and sex appeal: An analysis of #thinspiration images on popular social media. Body Image 14:54–61. 10.1016/j.bodyim.2015.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Juarascio AS, Shoaib A, Timko CA (2010). Pro-eating disorder communities on social networking sites: A content analysis. EatDisord 18:393–407. 10.1080/10640266.2010.511918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pater JA, Haimson OL, Andalibi N, Mynatt ED (2016). “Hunger hurts but starving works:” characterizing the presentation of eating disorders online. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 19th ACM Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing, San Francisco, California, USA. https://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2820030 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Syed-Abdul S, Fernandez-Luque L, Jian WS, Li YC, Crain S, Hsu MH et al. (2013). Misleading health-related information promoted through video-based social media: anorexia on YouTube. JMIR 15:e30 10.2196/jmir.2237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cornelius T, Blanton H (2016). The limits to pride: A test of the pro-anorexia hypothesis. Eat Disord 24:138–147. 10.1080/10640266.2014.1000102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holland G, Tiggemann M (2017). “Strong beats skinny every time”: Disordered eating and compulsive exercise in women who post fitspiration on Instagram. Int J Eat Disord 50:76–79. 10.1002/eat.22559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hefner V, Dorros SM, Jourdain N, Liu C, Tortomasi A, Greene MP et al. (2016). Mobile exercising and tweeting the pounds away: The use of digital applications and microblogging and their association with disordered eating and compulsive exercise. Cogent Social Sciences 2:1 10.1080/23311886.2016.1176304 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ali K, Farrer L, Fassnacht DB, Gulliver A, Bauer S, Griffiths KM (2017). Perceived barriers and facilitators towards help-seeking for eating disorders: A systematic review. Int J Eat Disord 50:9–21. 10.1002/eat.22598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bauer S, Moessner M (2013). Harnessing the power of technology for the treatment and prevention of eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord 46:508–515. 10.1002/eat.22109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: What is it, and what is it good for? (2007). Child Dev Perspect 1:68–73. 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2007.00016.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Common Sense (2015). The common sense census: media use by tweens and teens. https://www.commonsensemedia.org/sites/default/files/uploads/research/census_researchreport.pdf

- 26.Lenhart A (2015) Teens, social media & technology overview 2015. Pew Research Center. http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/04/09/teens-social-media-technology-2015/

- 27.PewResearchCenter (2018). Social Media Fact Sheet. http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/social-media/.

- 28.Bauermeister JA, Pingel E, Zimmerman M, Couper M, Carballo-Diéguez A, Strecher VJ (2012). Data quality in HIV/AIDS web-based surveys. Field Methods 24:272–291. 10.1177/1525822X12443097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Godinho A, Kushnir V, Cunningham JA (2016). Unfaithful findings: identifying careless responding in addictions research. Addiction 111:955–956. 10.1111/add.13221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leiner DJ (2013). Too fast, too straight, too weird: Post-hoc identification of meaningless data in Internet surveys. SSRN Electronic Journal. 10.2139/ssrn.2361661 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murray SB, Griffiths S, Mond JM (2016). Evolving eating disorder psychopathology: conceptualising muscularity-oriented disordered eating. Br J Psychiatry 208:414–415. 10.1192/bjp.bp.115.168427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hepp U, Milos G. (2002). Gender identity disorder and eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord 32:473–478. 10.1002/eat.10090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McClain Z, Peebles R (2016). Body image and eating disorders among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. Pediatr Clin North Am 63:1079–1090. 10.1016/j.pcl.2016.07.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Winston AP, Acharya S, Chaudhuri S, Fellowes L (2004). Anorexia nervosa and gender identity disorder in biologic males: A report of two cases. Int J Eat Disord 36:109–113. 10.1002/eat.20013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Graham AK, Trockel M, Weisman H, Fitzsimmons-Craft EE, Balantekin KN, Wilfley DE, Taylor CB (2019). A screening tool for detecting eating disorder risk and diagnostic symptoms among college-age women. J Am Coll Health 67:357–366. 10.1080/07448481.2018.1483936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Engel SG, Wittrock DA, Crosby RD, Wonderlich SA, Mitchell JE, Kolotkin RL (2006). Development and psychometric validation of an eating disorder-specific health-related quality of life instrument. Int J Eat Disord 39:62–71. 10.1002/eat.20200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ackard DM, Richter S, Egan A, Engel S, Cronemeyer CL (2014). The meaning of (quality of) life in patients with eating disorders: a comparison of generic and disease-specific measures across diagnosis and outcome. Int J Eat Disord 47:259–267. 10.1002/eat.22193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB (2001). The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 16:606–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JW, Löwe B (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The gad-7. Arch Intern Med 166:1092–1097. 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JW, Monahan PO, Löwe B(2007). Anxiety disorders in primary care: Prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med 146:317–325. 10.7326/0003-4819-146-5-200703060-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mossman SA, Luft MJ, Schroeder HK, Varney ST, Fleck DE, Barzman DH et al. (2017). The Generalize Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale in adolescents with generalized anxiety disorder: Signal detection and validation. Ann Clin Psychiatry 29:227–234a. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Richardson LP, McCauley E, Grossman DC, McCarty CA, Richards J, Russo JE et al. (2010). Evaluation of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 Item for detecting major depression among adolescents. Pediatrics 126:1117–1123. 10.1542/peds.2010-0852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cachelin FM, Striegel-Moore RH (2006). Help seeking and barriers to treatment in a community sample of Mexican American and European American women with eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord 39:154–161. 10.1002/eat.20213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Althouse AD (2016). Adjust for multiple comparisons? It’s not that simple. Ann Thorac Surg 101:1644–1645. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.11.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rothman KJ (1990). No adjustments are needed for multiple comparisons. Epidemiology 1:43–46. 10.1097/00001648-199001000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rubin M (2017). Do p values lose their meaning in exploratory analyses? It depends how you define the familywise error rate. Rev Gen Psychol 21:269–275. 10.1037/gpr0000123 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Casper RC (1998). Depression and eating disorders. Depress Anxiety 8:96–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Giovanni AD, Carla G, Enrica M, Federico A, Maria Z, Secondo F (2011). Eating disorders and major depression: role of anger and personality. Depress Res Treat 194732–194732. 10.1155/2011/194732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG, Kessler RC (2007). The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Biol Psychiatry 61:348–358. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kaye WH, Bulik CM, Thornton L, Barbarich N, Masters K (2004). Comorbidity of anxiety disorders with anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry 161:2215–2221. 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ziobrowski H, Brewerton TD, Duncan AE (2018). Associations between ADHD and eating disorders in relation to comorbid psychiatric disorders in a nationally representative sample. Psychiatry Res 260:53–59. 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lin LY, Sidani JE, Shensa A, Radovic A, Miller E, Colditz JB et al. (2016). Association between social media use and depression among u.s. young adults. Depress Anxiety 33:323–331. 10.1002/da.22466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zagorski N (2017). Using many social media platforms linked with depression, anxiety risk. Retrieved from https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2017.1b16

- 54.Housman LT (2017). “I’m home(screen)!”: social media in health care has arrived. Clin Ther 39:2189–2195. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2017.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Melioli T, Bauer S, Franko DL, Moessner M, Ozer F, Chabrol H, Rodgers RF (2016). Reducing eating disorder symptoms and risk factors using the internet: A meta-analytic review. Int J Eat Disord 49:19–31. 10.1002/eat.22477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Saffran K, Fitzsimmons-Craft EE, Kass AE, Wilfley DE, Taylor CB, Trockel M (2016). Facebook usage among those who have received treatment for an eating disorder in a group setting. Int J Eat Disord 49:764–777. 10.1002/eat.22567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sadeh-Sharvit S (2019).. Use of technology in the assessment and treatment of eating disorders in youth. Child Adol Psych 28:653–661. 10.1016/j.chc.2019.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chéileachair CN. Instagram and the regulation of eating disorder communities [Internet]. Bill of health: Examining the intersection of health law, biotechnology, and bioethics. 2017. [cited 24 September 2019]. Available from: http://blog.petrieflom.law.harvard.edu/2017/10/20/instagram-and-the-regulation-of-eating-disorder-communities/

- 59.Alexander A Instagram will restrict who can see posts about cosmetic procedures, weight loss products [Internet]. The Verge. 2019. [cited 24 September 2019]. Available from: https://www.theverge.com/2019/9/18/20872711/instagram-weight-loss-cosmetic-procedures-restrictions-policy-wellness-influencer-marketing

- 60.Austin SB, Hutcheson R, Wickramatilake-Templeman S, Velasquez K (2019). The second wave of public policy advocacy for eating disorders: Charting the course to maximize population impact. Psychiat Clin;42:319–336. 10.1016/j.psc.2019.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]