COVID-19 Outbreak and Pandemic Progression in Taiwan

On January 3, 2020, the World Health Organization was notified of 44 patients in Wuhan, China experiencing pneumonia of unknown cause, which was later identified as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Within 1 month the disease spread far beyond Wuhan, a city with a population of 11 million, and infected nearly 10,000 people in China.1 As the number of infected individuals continued to rise exponentially, China’s closest neighbors, such as Taiwan, Japan, and South Korea, soon faced the risk of their residents being infected.2 To date, more than 800 individuals in Japan and 8000 in South Korea have been diagnosed with COVID-19. With early proactive disease surveillance and contact isolation,3 Taiwan has had significantly fewer cases, with less than 100 confirmed cases and 1 death as of March 17, 2020.

Policies and Responses of the Health Care System in Taiwan

Taiwan has made tremendous efforts to minimize the spread of SARS-CoV-2 from abroad. The government has assigned overseas regions (subject to changes depending on updated data) to 1 of 3 levels with varying quarantine restrictions, with level 3 regions having the highest risk of infection. Residents who have returned from levels 1 and 2 regions are required to self-monitor for flu-like symptoms, and those from level 3 regions are placed under a mandatory 14-day home quarantine. Furthermore, foreigners with recent travel to level 3 regions are temporarily prohibited from entering Taiwan, and most flights from mainland China are grounded.3

To keep health care providers updated on the travel history of each resident, information from the immigration database is incorporated into the integrated circuit chip embedded in health insurance identification cards, which are issued by the National Health Insurance Administration and available to over 99% of the population. Additionally, distribution of personal protective equipment is under government supervision to avoid hoarding and assure availability.

Risk Control Strategies in Hospitals

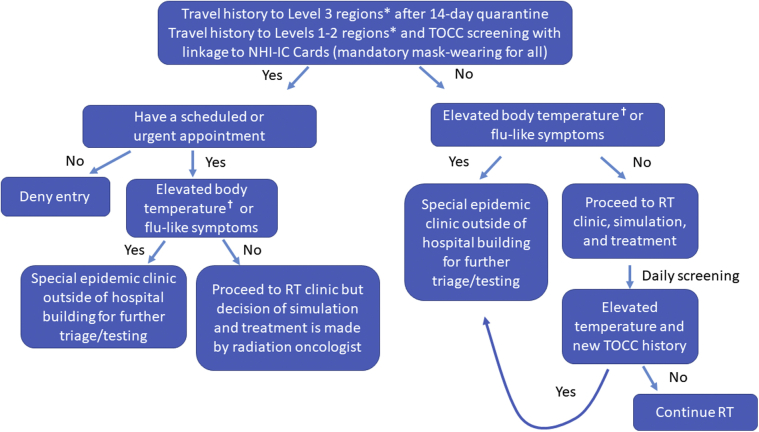

Hospitals throughout Taiwan have taken steps to minimize the virus spread.4 Figure 1 illustrates a typical hospital screening workflow. People who have returned from level 3 regions such as mainland China, Iran, Italy, South Korea, and certain European countries in the last 14 days are prohibited from entering hospitals unless they need to be seen in clinic for non-COVID-19–related illnesses or have suspected infection. The National Health Insurance Administration integrated circuit card, which is connected to the immigration database and contains the card holder’s travel and contact history, is verified by the medical staff before the card holder can enter a hospital for medical services; furthermore, everyone needing to enter a hospital, including patients, visitors, and staff members, is required to wear a disposable or cloth mask. Infrared thermal cameras are placed at hospital entrances, and individuals with abnormal thermal signals are rechecked for body temperature. Those with an elevated temperature (forehead temperature ≥37.5°C or tympanic temperature ≥38.0°C) are prohibited from entering and are subsequently referred to either the emergency department (travel history to level 3 regions) or the special epidemic clinic (including travel history to areas other than level 3 regions or suspicious travel/occupation/contact/cluster history) located outside the hospital building for further evaluation by infectious disease specialists. In addition, only up to 2 guests per patient are allowed to visit the clinic/inpatient floor for 1 hour per day to avoid overcrowding the hospital and minimize further spread outside the hospital.

Figure 1.

Screening workflow for patients entering hospitals and daily radiation treatments. ∗Designated by the government and subject to modification. †Forehead temperature ≥37.5°C or tympanic temperature ≥38.0°C. Abbreviations: NHI-IC = National Health Insurance Integrated Circuit (IC) chip; RT = radiation therapy; TOCC = travel/occupation/contact/cluster history.

Precautionary Measures in Radiation Oncology Departments

Patients with cancer are more vulnerable to infection owing to their compromised immune system, and active cancer therapy such as chemotherapy and radiation therapy (RT) may lead to further immunocompromised status. Hence, precautionary measures are necessary especially in radiation oncology departments where patients are present for daily or fractionated treatment (Fig 2). Common policies of radiation oncology departments in Taiwan for patients with reported or confirmed COVID-19 include postponing the simulation and scheduling RT after completion of the isolation and infection control requirements. The simulation and initiation of RT for patients arriving from level 3 regions and without COVID-19 symptoms are postponed for 14 days from their entry into Taiwan. In case of urgent medical necessity before completing the 14-day quarantine requirement, patients need to contact Taiwan’s Centers for Disease Control for approval to enter the hospital after following specific protocols. The quarantine restrictions also apply to scheduled follow-up and new consult patients. For patients coming from levels 1 and 2 regions in the last 14 days before their hospital appointment, the simulation or treatment, with the attending oncologist’s approval, can be scheduled for the end of the day after disinfection of the room. Patients continue to be screened daily, and those with new onset of fever, other flu-like symptoms, or new travel/occupation/contact/cluster history during RT course are referred to the onsite screening station for SARS-CoV-2 tests. Each patient is tested every 24 hours for 3 consecutive times, with a testing result turnaround of 24 hours. Those with 3 consecutive negative tests are allowed to resume RT. Some centers may consider hypofractionated regimens for infected individuals to finish RT faster, per treating physician’s discretion. Surgical masks for medical staff in the department are supplied on at least a daily basis and more frequently as needed. Notably, each patient undergoing RT is provided with a new surgical mask daily and is encouraged to wear it in public spaces outside the hospital. The treatment machines and equipment are disinfected between each patient, and treatment facilities are cleaned by trained staff in compliance with recommendations from the hospital’s infection control team.

Figure 2.

Picture of radiation therapists and an uninfected/low-risk/asymptomatic routine patient wearing personal protective equipment (PPE) during a radiation therapy (RT) session.

At some medical centers, the medical staff, including physicians, therapists, and nurses, are divided into mutually exclusive subgroups. Direct contact between members from each subgroup is prohibited. If any member of the subgroup encountered a suspicious COVID-19 case, the whole subgroup undergoes a 14-day quarantine. Meanwhile, other subgroups can still operate the department with the least amount of effect on medical service. Hospital meetings and tumor board conferences are either canceled, reduced in frequency, or take place via online video discussions. With these proactive preventive approaches, there has been no need to reduce clinical staff availability as a way to further reduce human contact and increase social distancing. All hospitals are able to maintain normal workforce to assist patients and provide cross coverage when needed, and there has been no SARS-CoV-2 transmission in the radiation oncology departments in Taiwan.

Challenges Affecting Radiation Oncology Patients and Clinical Staff

With initial success in containing COVID-19 spread in Taiwan, impact on RT service is minimal. For example, at the Department of Radiation Oncology at National Taiwan University Hospital, which maintains a daily treatment volume of 300 to 350 patients in 2 shifts, the rate of postponing or canceling RT simulations for all causes was 16.9% (73 of 431) from February 15 to March 15, 2020, comparable to the 16.4% (77 of 471) in the same period in 2019. By providing adequate screening and preventive measures for the patients and staff, there was no need for rationing RT or treatment delay in otherwise uninfected/nonquarantined individuals. Sixty-one inpatient RT consultations were seen from February 15 to March 15, 2020, similar to 57 in the same period in 2019. Two patients were referred to the epidemic screening process and had subsequent negative COVID-19 test results, and no patient undergoing RT had COVID-19.

Despite this achievement, there has been an unavoidable influence on patients and health care professionals. Patients who are concerned about acquiring the infection may choose to postpone clinic visits, despite not having a departmental policy to recommend the delay. In addition, patients who were planned for RT may decide to defer the recommended therapy, especially with palliative or elective treatment.5 The shortage of medical supplies for personal protective equipment and fear of getting infected inside hospital buildings make it stressful for both patients and health care professionals.6,7 All of this might affect the interaction between patients and health care professionals,8 influence important decision-making processes, and potentially determine cancer therapy outcome.

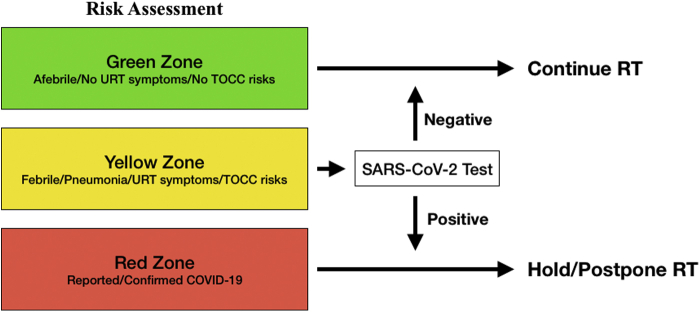

As COVID-19 evolves into a global pandemic, the risk of community spread in Taiwan could continue to increase. A proposed modified workflow that separates RT patients into different physical waiting and treatment spaces and “zones” in case of increased community spread is presented in Figure 3. In addition, the government is considering nationwide screening of all health care professionals for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies to detect past infection and current asymptomatic infections to better triage frontline health care workers.

Figure 3.

Conceptual risk stratification strategy for patients requiring radiation therapy (RT) service during the community spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Abbreviations: TOCC = travel/occupation/contact/cluster history; URT = upper respiratory tract.

Lessons for Radiation Oncology from SARS Experiences for COVID-19

Taiwan went through the SARS epidemic in 2013, with 181 deaths of 668 probable infected patients.9 Because of its high nosocomial infection and mortality rates, SARS led to the closure of medical units and isolation of many health care professionals in Taiwan, resulting in over 20% of RT treatment volume reduction. Because of lessons learned from the SARS outbreak and concerns for other seasonal infections in a densely populated country, and a response to air pollution, Taiwanese residents, regardless of their health status, developed the habit of wearing masks in public.

Taking all the information into consideration, hospitals have adapted an updated policy to screen high-risk individuals by isolating them in designated areas outside hospital buildings to protect uninfected people and health care professionals,10 taking highly hygienic steps by mandating mask-wearing for everyone inside hospital buildings, and disinfecting waiting areas and treatment units between patients. The strategies to deal with COVID-19 versus SARS mean that the current workflow of fractionated RT can be cautiously maintained.

Conclusions

With experience gained from the SARS epidemic, the Taiwanese government’s efficient policies and strategies, and a multitude of precautionary steps implemented by hospitals, departments of radiation oncology in Taiwan have been able to provide uninterrupted radiation treatment for most patients with cancer amid the current COVID-19 pandemic. Taiwan’s strategic plans for limiting the spread could be a useful resource for other regions facing this serious public health threat.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Taiwan Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwanese healthcare professionals, and all Taiwanese people for their supports.

Footnotes

Sources of support: This work had no specific funding.

Disclosures: none.

References

- 1.Lai C.C., Shih T.P., Ko W.C. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SAR-CoV-2) and coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19): The epidemic and the challenges. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;55:105924. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheng S.C., Chang Y.C., Fan Chiang Y.L. First case of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc. 2020;119:747–751. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2020.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang CJ, Ng CY, Brook RH. Response to COVID-19 in Taiwan: Big data analytics, new technology, and proactive testing [epub ahead of print]. JAMA. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.3151, accessed March 15, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Lee IK, Wang CC, Lin MC, et al. Effective strategies to prevent coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in hospital [epub ahead of print]. J Hosp Infect. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhin.2020.02.022, accessed March 15, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Lee J., Holden L., Fung K. Impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome on patient access to palliative radiation therapy. Support Cancer Ther. 2005;2:109–113. doi: 10.3816/SCT.2005.n.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lung F.W., Lu Y.C., Chang Y.Y., Shu B.C. Mental symptoms in different health professionals during the SARS attack: A follow-up study. Psychiatr Q. 2009;80:107–116. doi: 10.1007/s11126-009-9095-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peng E.Y., Lee M.B., Tsai S.T. Population-based post-crisis psychological distress: An example from the SARS outbreak in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc. 2010;109:524–532. doi: 10.1016/S0929-6646(10)60087-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tang J.I., Shakespeare T.P., Zhang X.J. Patient satisfaction with doctor-patient interaction in a radiotherapy centre during the severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak. Australas Radiol. 2005;49:304–311. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1673.2005.01467.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen K.T., Twu S.J., Chang H.L. SARS in Taiwan: An overview and lessons learned. Int J Infect Dis. 2005;9:77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2004.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwartz J, King CC, Yen MY. Protecting health care workers during the COVID-19 coronavirus outbreak: Lessons from Taiwan's SARS response [epub ahead of print]. Clin Infect Dis. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa255, accessed March 15, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]