With 10·93 deaths per million people from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), as of April 6, 2020, Ecuador has one of the highest rates of COVID-19 mortality in Latin America (figure ; appendix).1 With only 7·46 PCR tests per 10 000 people,1 the government is in critical need of a systematic mechanism to bolster self-reporting, contact tracing, and effective isolation of suspected cases. The Ministry of Health has focused on closing gaps in medical resources by increasing availability of personal protective equipment and hospital beds and attempting to remedy overburden of health-care facilities and mortuary services in Guayas province, the country's main hotspot of the outbreak (appendix), but 417 health personnel in Ecuador have COVID-19.2

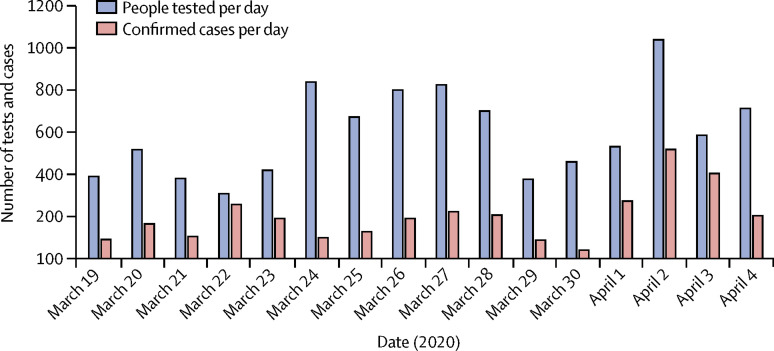

Figure.

Daily number of tests and confirmed cases of coronavirus disease 2019 in Ecuador, from March 19 to April 4, 2020

Data source: Ministry of Health of Ecuador.1

Given the low number of tested individuals (13 039 tested in a country with 17·47 million people),1 it is likely that only symptomatic cases and close contacts of confirmed cases are being tested, probably because of limited test availability. The 23-day lockdown has been unevenly enforced, allowing people to concentrate in public places where circulation is allowed. Mobile phone use is not universal,3 making self-reporting and case monitoring challenging, particularly for disadvantaged people such as indigenous populations and the more than 350 000 Venezuelan refugees.4

Ecuador lacks universal health coverage and medical records that can be accessed virtually across public and private providers. However, the country has capacity, from civil society organisations, local political offices, and public institutions with knowledge of and contact with their communities,5 that could contribute to containment and mitigation efforts. These local multisector structures could help adopt a modular testing and informational strategy that would curb unnecessary mobility and pressure on health-care facilities.

Local multisectoral structures could function as health and surveillance clusters that register epidemiological data, trace contacts (including contacts of confirmed and suspected cases that have already been tested), and support close monitoring of mild and asymptomatic symptoms in people with confirmed or suspected infection. Managing the COVID-19 epidemic locally would allow verified recommendations that promote uptake of personal measures to be disseminated effectively (and in native languages) and would help channel complementary resources, such as food, to ensure proper isolation of cases.

Depending on context, such as local communication capabilities and geographical and ethnic factors, each health and surveillance cluster would be responsible for modules of about 1000 households. Health centres would aggregate data to improve epidemiological modelling and provide specialist support. Where infection incidence is low, potential clusters should already begin to work, convening local stakeholders to assess existing social assets and potential support from the wider health system.

Acknowledgments

We declare no competing interests.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Ministry of Health of Ecuador COVID-19 epidemiological bulletins. 2020. https://www.salud.gob.ec/gacetas-epidemiologicas-coronavirus-covid-19/ (in Spanish).

- 2.Ecuavisa 417 profesionales de la salud en Ecuador tienen COVID-19. April 6, 2020. https://www.ecuavisa.com/articulo/noticias/nacional/587541-417-profesionales-salud-ecuador-tienen-covid-19

- 3.Ministerio de Telecomunicaciones y Sociedad de la Información . Ministerio de Telecomunicaciones y de la Sociedad de la Información; Quito: 2018. Libro Blanco de la Sociedad de la Información y del Conocimiento. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Regional Inter-Agency Coordination Platform for Refugees and Migrants from Venezuela Plataforma de coordinación para refugiados y migrantes de Venezuela 2019. Dec 31, 2019. https://r4v.info/es/situations/platform/location/7512

- 5.Torres I, López-Cevallos DF. Institutional challenges to achieving health equity in Ecuador. Lancet Global Health. 2018;6:e832–e833. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30245-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.