Abstract

Antisocial peer behavior and low parental knowledge of adolescents’ activities are key interpersonal risk factors for adolescent substance use. However, how the magnitude of associations between these risk factors and substance use may vary across adolescence remains less well understood. The present study examined the age-varying associations of parental knowledge and antisocial peer behavior with adolescents’ substance use (i.e., cigarette use, drunkenness, and marijuana use) using time-varying effect modeling. Using data from the Promoting School-Community-University Partnerships to Enhance Resilience (PROSPER) study, the final sample consists of 8222 adolescents, followed from Grade 6 to Grade 12 (age 11 to age 18.9), including those who newly joined the schools at the targeted grade-levels. Results showed that low parental knowledge and antisocial peer behavior were significantly associated with the use of each of the three substances across the majority of adolescence. The magnitude of the associations between substance use and both risk factors decreased across age, except between peer risk and marijuana use. Further, there was a significant interaction between parent and peer risk factors such that low parental knowledge was less strongly associated with substance use at high levels of antisocial peer behavior. Findings highlighted early adolescence as an important period to target parent and peer prevention and interventions for reducing early substance use.

Keywords: Parental knowledge, antisocial peer, substance use, time-varying effect modeling, adolescence

Introduction

Substance use initiation commonly occurs during adolescence and prevalence increases over the course of this developmental period (Chassin, Hussong, & Beltran, 2009; Young et al.,2002) According to a national survey on adolescent drug use, the past-month prevalence for cigarette use, drunkenness, and marijuana use increases substantially with age; specifically, 1.9%, 2.2%, and 5.5% of eighth graders versus 9.7%, 19.1%, and 22.9% of twelfth graders engaged in cigarette use, drunkenness, and marijuana use respectively in the past month (Johnston et al., 2018). Although there are specific risks for each of these substances, family and peer influences have been identified as general risk factors for all three (Fergusson, Swain-Campbell, & Horwood, 2002; Van Ryzin, Fosco, & Dishion, 2012). The influence of these risk factors, however, may not be constant across age as individuals and their family and peer relationships undergo significant transformations in development including changes in closeness with parents and peers from childhood to adolescence as well as individuals’ growing autonomy (Buhrmester & Furman, 1987; Wray-Lake, Crouter, & McHale, 2010). These changes in the nature of parent and peer relationships across adolescence may influence the strength of associations of parent and peer risk factors with substance use across this developmental period. Although there is a large body of longitudinal research on adolescent substance use, little is known about how the magnitude of associations (i.e., effect size) of family and peer factors with substance use outcomes varies by age. Research focusing on age-varying associations between interpersonal contexts and substance use could help identify ages at which adolescents are particularly vulnerable to certain risk factors, which may inform the timing and targeting of interventions. In the current study, we examine how the associations of parental knowledge and antisocial peer behavior with substance use (i.e., cigarette use, drunkenness, and marijuana use) change as a function of age across adolescence.

Substance Use, Parental Knowledge, and Antisocial Peer Behavior

Adolescent substance use is associated with both short- and long-term consequences. Short-term consequences include impaired judgement and performance, driving under the influence, accidents, and risky sexual behaviors; long-term consequences include continued substance use, substance dependence, and other mental health problems in adulthood (Chassin et al., 2009), particularly if substance use initiation occurs early (i.e., prior to age 15; Grant & Dawson, 1997; Odgers et al., 2008). Cigarettes, alcohol, and marijuana are three of the most commonly used substances in adolescence (Johnston et al., 2018); the use of these common substances may predict subsequent involvement with other illicit drugs (Kandel & Jessor, 2002). Of all substances used among adolescents, alcohol is the most prevalent one (Johnston et al., 2018). Research suggests that drunkenness, compared to alcohol use, is a stronger predictor of adjustment problems in adolescence and beyond (Hingson, Heeren, Winter, & Wechsler, 2003; Kuntsche et al., 2013; Lintonen, Rimpelä, Vikat, & Rimpelä, 2000).

Two of the most important relationships in adolescence are parents and peers, with whom adolescents interact with on a regular basis, and they play a crucial role in adolescents’ successful adjustment (Collins & Steinberg, 2008; Sameroff, Seifer, & Bartko, 1997; Smetana, Campione-Barr, & Metzger, 2006). Developmental theories such as Patterson and colleagues’ (1989) developmental theory on antisocial behavior and Dishion and colleagues’ (2004) perspective on premature adolescent autonomy highlight the important roles parents and peers play in adolescents’ development of problem behaviors, which have been extended to understand adolescent substance use. Specifically, Patterson and colleagues’ (1989) developmental theory suggests that children and adolescents with ineffective parenting (e.g., low parental knowledge, harsh parenting, or inconsistent discipline) are more likely to develop problem behaviors that could result in the rejection by mainstream peers, which subsequently could lead to their affiliation with antisocial peers and as a results, adolescents engage in more problem behaviors, including substance use. Past research has identified low parental knowledge and antisocial peer behavior as important shared interpersonal risk factors across various adolescent substance use outcomes (Fergusson et al., 2002; Van Ryzin et al., 2012). Parental knowledge - one important facet of parental monitoring - refers to parents’ knowledge of the whereabouts and activities of their children and is one of the most widely studied family factors in relation to adolescent substance use. Although advances in the study of parental monitoring has led to distinctions between knowledge and monitoring (e.g., Racz & McMahon, 2011; Stattin & Kerr, 2000), parental knowledge remains an important predictor of adolescent substance use (Kerr & Stattin, 2000; Lippold, Coffman, & Greenberg, 2014). In families with low parental knowledge, parents are relatively unaware of their adolescents’ activities, whereabouts, or the peers with whom they spend time. Thus, adolescents may take advantage of these opportunities to engage in substance use without their parents knowing and parents are thus challenged to intervene in time to reduce these behaviors. Adolescent substance use often occurs in the context of antisocial peers (Ary et al., 1999). These peers engage in delinquent or antisocial behaviors and they are more likely to approve and encourage substance use in others through deviancy training (Dishion, McCord, & Poulin, 1999). Antisocial behaviors and substance use tend to co-occur and these behaviors are considered part of the broader problem behavior syndrome (Jessor, 1991; Jessor & Jessor, 1977).

Past research has shown that both low parental knowledge and antisocial peer behavior are consistently associated with adolescent alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use. Specifically, low parental knowledge and antisocial peer behavior are associated with increases in rank order (Cleveland, Feinberg, Bontempo, & Greenberg, 2008; Van Ryzin et al., 2012) as well as in levels and growth rates of adolescent substance use across time (Barnes, Hoffman, Welte, Farrell, & Dintcheff, 2006). Most of the existing research shows that these family and peer influences are shared risk factors across a number of substance use outcomes (Bahr, Hoffmann, & Yang, 2005; Cleveland et al., 2008; Rai et al., 2003; Van Ryzin et al., 2012). Although evidence regarding the direction of associations of parental knowledge and antisocial peer behavior with adolescent substance use is clear, less is known about how the magnitude of associations between these risk factors and substance use may vary across adolescence.

Developmental Changes in Potency of Risk Factors Across Adolescence

The strength of associations between interpersonal risk factors and adolescent substance use may vary developmentally due to considerable reorganization of interpersonal relationships in adolescence. As individuals develop from childhood to adolescence, they spend less time with parents and engage in less intimate disclosure with them but the opposite is true for peers (Buhrmester & Furman, 1987). At the same time, individuals are also gaining increasing autonomy across adolescence (Wray-Lake et al., 2010). These developmental changes point to the possibility that the potency of interpersonal influences may change across adolescence, which would be reflected in changes in the magnitude of associations of parental knowledge and antisocial peer behavior with substance use over the course of adolescence. For instance, it is possible that antisocial peer approval for substance use may become increasingly influential whereas parental knowledge may matter less with age, but it is also possible that both parental knowledge and antisocial peer behavior have decreasing influence on adolescent substance use as individuals are exposed to increasing number of social influences as well as growing autonomy over time. For example, as adolescents get older, their decision to engage in substance use or not may not be as much dependent on whether parents know about it, but also depends on many other factors such as peer norms, influence of romantic partners, and their own values and beliefs about substance use. Preliminary support for age-varying associations is found in prior work documenting that parental knowledge was generally more strongly associated with adolescent substance use in early adolescence compared to later adolescence (Cleveland et al., 2008; Van Ryzin et al., 2012), suggesting that this association may decline with age during adolescence. Similarly, there is evidence that the magnitude of association between antisocial peer behavior and substance use also decreases across adolescence (Fergusson, Swain-Campbell, & Horwood, 2002). However, findings regarding the strength of this association across adolescence are less consistent. Although age-varying associations were not explicitly examined, other findings suggest that the strength of this association may increase across age (Cleveland et al., 2008), decrease initially in early adolescence and then increase again around middle to late-adolescence (Schuler, Tucker, Pedersen, & D’Amico, 2019), or vary across substances (Van Ryzin et al., 2012).

To date, extant literature characterizing developmental changes in the magnitude of parent and peer influences faces challenges in conceptualizing them across development. Preliminary evidence regarding age-varying associations is often based on analyses run separately at different age periods or age is inferred from the approximate age of adolescents in certain waves or grades rather than using adolescents’ actual continuous age. While these approaches are justifiable, they are limited because “cutting” the age dimension into a small number of categories does not allow for the emergence of more nuanced age-related change trajectories and using approximate age of adolescents in waves or grades could obscure age trends due to age variation within a wave or a grade level. Furthermore, findings from using discrete time models (e.g., structural equation models with panel designs) are sometimes hard to replicate because the strength of associations depends on how coarsely time (e.g., age) is categorized, which may contribute to inconsistent findings across studies.

Recent studies have begun using continuous time modeling methods such as time-varying effect modeling (TVEM) to examine age-varying associations of risk and protective factors for adolescent substance use (Epstein et al., 2017; Lanza & Vasilenko, 2015; Lydon-Staley & Geier, 2018; Schuler et al., 2019; Selya, Dierker, Rose, Hedeker, & Mermelstein, 2016). Studies examining family and peer risks have provided support for age-varying associations between these risks factors and substance use (Epstein et al., 2017; Schuler et al., 2019). Particularly relevant to the current study, Epstein and colleagues (2017) have examined the age-varying effects of family management and antisocial peer behavior on marijuana use across adolescence. They found that both family management and antisocial peer behavior were significantly associated with marijuana use across adolescence and the associations were generally steady across time. Building on Epstein and colleagues’ (2017) study, the present study extends their work in at least two important ways. First, we expanded the outcomes beyond marijuana use, to provide information about the age-varying associations of family and peer risks with cigarette use and drunkenness. Second, we evaluated family management and antisocial peer behavior in the same model, making it possible to draw conclusions about the unique contributions of parents and peers on adolescent substance use. An added benefit of simultaneously evaluating parent and peer influences on adolescent substance use is the ability to test whether there are dependencies in risk (i.e., interactive effects). For instance, the influence of low parental knowledge on substance use may be weaker or stronger depending on the level of antisocial peer behavior.

Most research to date has primarily examined parent and peer influences separately, leaving less clear the degree to which parent and peers may be interdependent influences on adolescent development. For example, Dishion and colleagues (2003, 2004) theorized that in face of higher levels of antisocial peers, parents may relinquish their monitoring of adolescents. This has been conceptualized as “premature adolescent autonomy,” a process in which family disengagement, in conjunction with adolescent involvement with deviant peers, is a key risk context for adolescent antisocial behavior, sexual promiscuity, and substance use (Dishion et al., 2004; Fosco & LoBraico, 2018, 2019). Among the limited research that has examined the interaction between parental knowledge and antisocial peer behavior predicting adolescent substance use, some evidence suggests that the association between low parental knowledge and substance use is stronger when peer deviance is high (Kiesner, Poulin, & Dishion, 2010; Svensson, 2003) whereas others suggest there is no evidence for such an interaction (Trucco, Colder, & Wieczorek, 2011; Wood, Read, Mitchell, & Brand, 2004). Nevertheless, these findings on interaction between parents and peers were based on analyses conducted on one or two age groups in adolescence rather than over the course of adolescence, thus do not reveal the dynamic interaction process across development.

The Present Study

Preliminary evidence suggests that the strength of association of low parental knowledge and antisocial peer behavior with adolescent substance use may be age-varying. However, this evidence is based on analyses in which individuals are grouped by grades, waves, or age categories as commonly used in traditional panel longitudinal research. Therefore, more subtle shifts in the strength of associations across development may be obscured. This calls for methods to examine the strength of associations between predictors and substance use continuously throughout development. TVEM is one approach that allows for flexible estimation of the strength of associations between predictors (i.e., parental knowledge and antisocial peer behavior) and an outcome (e.g., cigarette use) across continuous age (Lanza, Vasilenko, & Russell, 2016; Tan, Shiyko, Li, Li, & Dierker, 2012). TVEM can provide important information regarding ages at which adolescents are more susceptible to specific influences, which would guide the timing and targets for prevention and interventions.

The present investigation is the first to use TVEM to simultaneously evaluate age-varying associations of parental knowledge and antisocial peer behavior with adolescent cigarette use, heavy alcohol use (i.e., drunkenness), and marijuana use. This provides a careful examination of unique associations of family and peer risks with substance use. Furthermore, examining family and peer risks simultaneously also allows for the examination of possible dynamic interactions between them. This would provide important information regarding the role of parental knowledge for adolescents with different levels of peer risk.

In the present study, we seek to address the following research questions:

-

1)

How are low parental knowledge and antisocial peer behavior associated with adolescents’ past-month cigarette use, drunkenness, and marijuana use across ages 11 to 18.9?

-

2)

How do the age-varying associations between low parental knowledge and each of the substance use outcomes differ as a function of antisocial peer behavior?

Methods

Participants

The current study used data from the large-scale randomized effectiveness trial of the Promoting School-Community-University Partnerships to Enhance Resilience (PROSPER) intervention delivery system for evidence-based interventions aimed at reducing substance use among rural adolescents (Spoth, Greenberg, Bierman, & Redmond, 2004). Participants in PROSPER were two successive cohorts of sixth graders in 28 rural and semi-rural communities in Iowa and Pennsylvania. The PROSPER delivery system supported the implementation of a family-focused preventive intervention for sixth graders and their parents in the intervention communities and a school-based preventive intervention when they were in seventh grade. Approval was obtained from the Pennsylvania State University Institutional Review Board (IRB #00038100; “PROSPER: In-School Surveys and Continuing Longitudinal Data Collection”). As the current study aimed to examine the developmental timing of substance use and the age-varying associations of family and peer predictors with substance use, the current sample included only participants from the control communities.

Participants were followed from sixth grade (Wave 1; Cohort 1: 2002 and Cohort 2: (2003) to twelfth grade (Wave 8; Cohort 1: 2009 and Cohort 2: 2010); participants who joined the schools within this period at the targeted grade-levels were also included. To enhance the precision of our modeling estimates, we restricted our analyses to the age range of 11 to 18.9 years because few individuals provided data outside these ages (thus excluding only 0.6% of all observations). The final sample comprised 8,222 participants (49.8% males and 50.2% females), and each person on average provided 4.8 observations. Adolescents reported their race as White (78.3%), Latino/Hispanic (6.5%), Black/African-American (5.1%), Native American/American Indian (1.9%), Asian (1.5%), and others (6.7%).

Measures

Measures of substance use, parental knowledge, and antisocial peer behavior were adapted measures established in prior large-scale longitudinal projects and studies (Conger, 1989; Lippold et al., 2014; Lippold, Fosco, Ram, & Feinberg, 2016; Redmond, Spoth, Shin, & Lepper, 1999)

Past-month substance use.

Adolescents reported on their frequency of past-month cigarette use, drunkenness, and marijuana use by responding to three separate, one-item measures: “during the past month, how many times have you 1) smoked any cigarettes; 2) been drunk from drinking wine, wine coolers, or other liquor; and 3) smoked marijuana (pot, reefer, weed, blunts)”. Adolescents responded to each item on a 5-point scale (1 = not at all to 5 = more than once a week). Responses were dichotomized to indicate whether or not adolescents had used a specific substance in the past month (0 = no, 1 = yes) as the majority of the sample were non-users in the past month.

Parental knowledge.

Adolescents responded to five items assessing their parents’ knowledge of their adolescents’ activities, whereabouts, and people who they spend time with when they are not at home. This measure had been referred to as child monitoring in previous studies (e.g., Redmond et al., 1999). The five items were “during the day, my parents know where I am”, “my parents know who I am with when I am away from home”, “my parents know when I do something really well at school or some place else away from home”, “my parents know when I get into trouble at school or some place else away from home”, and “my parents know when I do not do things they have asked me to do”. Each item was rated on a 5-point scale (1 = never to 5 = always). Responses to the five items were averaged and reverse-coded so that higher scores indicated lower parental knowledge (i.e., higher risk). Reverse coding parental knowledge helps with the interpretation of the relative effect size (i.e., odds ratios) of the two risk factors. The Cronbach alphas ranged from .76 to .90 across waves.

Antisocial peer behavior.

Adolescents reported on their friends’ antisocial behaviors using three items on a 5-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). Adolescents were asked how much they agree with each of the three items describing their closest friends: “these friends sometimes get into trouble with the police”, “these friends sometimes break the law”, and “these friends don’t get along very well with their parents”. Responses to the three items were averaged and higher scores represented higher levels of antisocial peer behavior. The Cronbach alphas ranged from .79 to .83 across waves.

Covariates.

Adolescents reported on free or reduced-price lunch in school (0 = no, 1 = yes) at each wave, which was used as an indicator of family economic disadvantage. Adolescents reported on who they currently lived with at each wave; responses were coded to indicate whether they were living with both biological parents (0 = no, 1 = yes). Adolescents also reported their gender (0 = female and 1 = male) and race (0 = non-white and 1 = white).

Analysis Plan

Before conducting core analyses, we evaluated attrition in our sample. However, it should be noted that attrition is not straightforward to define in this study because students who joined the school subsequently at the targeted grade levels where data collection occurred were also included. Nevertheless, to facilitate comparisons with traditional cohort studies, we defined attriters as those who participated at Wave 1 but did not participate at a subsequent wave in order to evaluate how attriters and completers differ in main demographic characteristics. If differences were found, we included those variables as covariates in the TVEM models examining age-varying associations between predictors and outcomes to reduce biases that might have been introduced into the estimation process.

All subsequent models were conducted using TVEM, a direct extension of multiple regression in which regression coefficients are allowed to vary as a function of continuous time (or age). The TVEM approach is flexible enough to allow the emergence of nonparametric change trajectories in regression coefficients to emerge, meaning that there is no a priori constraint placed on the shapes of the intercept and slope functions (Tan et al., 2012). Estimates include an intercept function and slope functions, which represent the associations between predictors and an outcome across continuous time. All TVEM models were fit using truncated power basis splines (p-splines) in the TVEM SAS macro, which can be downloaded at methodology.psu.edu (Li, Dziak, Huang, Wagner, & Yang, 2017). Model selection for p-spline bases is done via an automatic process in which the user specifies an ample maximum number of knots for each coefficient function (10 knots were specified for each function in the current analysis). Then, the model applies a smoothing parameter that optimally shrinks knot coefficients toward zero, thereby capturing complexity while protecting against overfit (Tan et al., 2012). Standard errors were estimated using the Huber-White “sandwich” formula, which adjusts standard errors to account for the clustering of repeated observations within individuals.

For descriptive purposes, we conducted five TVEM intercept-only models to understand how levels of the two predictors and prevalence of three substance use outcomes vary across adolescence. First, two separate TVEM intercept-only models were used to examine how the levels of the two predictors (i.e., parental knowledge and antisocial peer behavior) change across adolescence. A sample model equation (e.g., parental knowledge) is:

where i is the index for person (i = 1, 2, . . . , n), j is the index of measurement occasions (j = 1, 2, . . . , T), and tij is the age value for person i at time j. Next, three separate intercept-only logistic TVEM models were specified to examine prevalence rates of past-month cigarette use, drunkenness, and marijuana use by age. A sample model equation (e.g., cigarette use) is:

Regarding age-varying associations, logistic TVEM was used to estimate the associations of parent and peer predictors with the odds of past-month cigarette use, drunkenness, and marijuana use from ages 11 to 18.9 in three separate sets of models, with each set corresponding to one substance use outcome. Both predictors were standardized across all observations before the analyses. For each substance use outcome, we examined a) age-varying associations of low parental knowledge and antisocial peer behavior with past-month substance use and b) the age-varying associations between low parental knowledge and past-month substance use as a function of antisocial peer behavior. Gender and race were included as time-invariant covariates and indicators of living with both biological parents and free or reduced-price lunch were included as time-varying covariates in each model.

The model equation for examining age-varying associations of low parental knowledge and antisocial peer behavior with each past-month substance use outcome is:

The model equation for examining age-varying associations between low parental knowledge and each substance use outcome as a function of antisocial peer behavior is:

Results

Before conducting TVEM analyses, we evaluated attrition in our sample. For all adolescents participated in Wave 1 (the primary cohort; N=5299), the retention rates were 91%, 83%, 78%, 74%, 65%, 55%, and 50% from Wave 2 to Wave 8 respectively. However, it should be noted that students who joined the school subsequently at the targeted grade levels where data collection occurred “replenished” the sample. The resulting sample sizes of Wave 2 through Wave 8 were 99% (W2), 105% (W3), 105% (W4), 106% (W5), 95% (W6), 82% (W7), and 76% (W8) of the sample size at Wave 1. To conduct attrition analyses, we examined the retention rate of the primary cohort. Attriters at Wave 8, compared to completers, were more likely to be male (t (4964.3) = −4.04), non-white (t (5199.5) = 6.22), receiving free or reduced-price lunch (t (5038.7) = −14.28), and less likely to be living with both biological parents (t (5180.7) = 14.60) at Wave 1 (ps < .05). These demographic variables were added subsequently as covariates in the TVEM models examining age-varying associations between interpersonal predictors and substance use outcomes to reduce potential biases. Also, TVEM models were run based on complete data for each record in the long format. In other words, if a participant had missing data on a model’s variable(s) in a wave, the person’s data for that wave would be excluded from the analytic model, but his or her data for other waves were still included in the analysis. Nonetheless, the proportion of missing data due to missing responses was relatively low, about 91.8% to 99.9% of all observations were included in the analysis models.

Intercept-only TVEM models provided descriptive information on two key interpersonal predictors and three substance use outcomes. Specifically, the level of parental knowledge declined steadily with age throughout adolescence whereas the level of antisocial peer behavior increased throughout early to middle adolescence and then leveled off (Figure 1a and 1b). Low parental knowledge and antisocial peer behavior were correlated across age in this study (r = .32 to r = .44). To examine the prevalence rates of past-month substance use, we specified intercept-only models to characterize the rates of past-month cigarette use, drunkenness, and marijuana use by age (Figure 2). The three solid curves represent the estimated prevalence of each of the past-month substance use as a function of age. Dotted lines represent 95% confidence intervals around the estimated curves. Past-month substance use was minimal at age 11 and increased across adolescence. Cigarette use increased steadily from age 11 to age 18.9 (32.0%); drunkenness increased at a slower rate than cigarette use between ages 11 and 13 and increased more rapidly afterwards through age 18.9 (38.7%); marijuana use increased at the slowest rate of all three substances before age 13 and then increased steadily to age 16 and the increase decelerated somewhat from age 16 to age 18.9 (21.2%). Before age 15, past-month cigarette use was most common, followed by drunkenness, and marijuana use. By age 15, the rates of past-month drunkenness exceeded the rates of past-month cigarette use. Correlations among all variables at each wave could be found in supplemental materials.

Figure 1a.

Estimated mean level of parental knowledge across age (Nperson = 8164, Nobs = 38562).

Figure 1b.

Estimated mean level of antisocial peer behavior across age (Nperson = 8203, Nobs = 39167).

Figure 2.

Estimated rates of past-month cigarette use, drunkenness, and marijuana use (Nperson = 8220, Nobs = 39438; Nperson = 8221, Nobs = 39365; Nperson = 8217, Nobs = 39331, respectively).

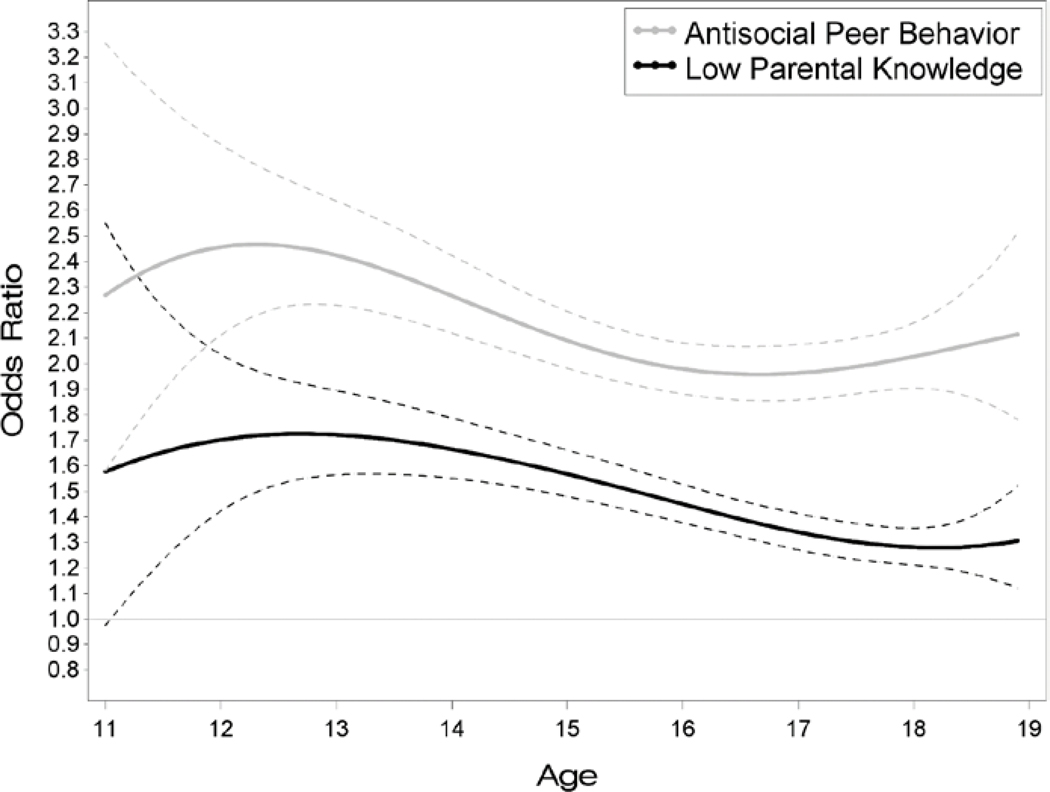

Next, we specified three sets of models to estimate age-varying coefficients representing the associations of low parental knowledge and antisocial peer behavior with each substance use outcome as well as the interaction between parent and peer risks in predicting each substance use outcome. Each model included covariates indicating adolescents’ gender, race, living with both biological parents, and the receipt of free or reduced-price lunch. The associations between parent and peer predictors and substance use outcomes are presented as odds ratios; 95% confidence intervals that do not include the value 1 indicate statistically significant associations at that specific age.

First, the age-varying associations between interpersonal risk factors and adolescents’ past-month cigarette use were examined (Figure 3a). Controlling for antisocial peer behavior, low parental knowledge was associated with cigarette use across ages 11 to 18.7. This association was strongest at age 12.1 (OR = 1.71; 95% CIs [1.55, 1.89]) and gradually declined in magnitude until it was no longer statistically significant after age 18.7. Controlling for parental knowledge, antisocial peer behavior was significantly associated with cigarette use across all ages, but the magnitude changed over time in a pattern consistent with an inverted-U shaped curve across ages. The association between antisocial peer behavior and cigarette use was strongest at age 13.7 (OR = 2.29; 95% CIs [2.15, 2.45]). Finally, the association between low parental knowledge and cigarette use differed significantly as a function of antisocial peer behavior (Figure 3b). The black and grey lines indicate the association between low parental knowledge and cigarette use when antisocial peer behavior was one standard deviation (SD) above and below the mean, respectively. As shown in Figure 3b, the association between low parental knowledge and cigarette use was significantly weaker for adolescents with higher versus lower antisocial peer behavior from ages 11.6 to 17.9.

Figure 3a.

Age-varying associations of low parental knowledge and antisocial peer behavior with past-month cigarette use (Nperson = 7928, Nobs = 36334).

Figure 3b.

Age-varying association between low parental knowledge and past-month cigarette use as a function of antisocial peer behavior. Box indicates age range (11.6 to 17.9) of significant moderation (Nperson = 7928, Nobs = 36334).

Second, the age-varying associations between interpersonal risk factors and adolescents’ past-month drunkenness were examined (Figure 4a). Low parental knowledge was significantly associated with past-month drunkenness across ages 11.1 to 18.9 and antisocial peer behavior was significantly associated with drunkenness across all ages. The odds ratios were 1.59 (95% CIs [1.02, 2.49]) for low parental knowledge and 2.29 (95% CIs [1.63, 3.21]) for antisocial peer behavior at age 11.1 and both decreased slightly with age. Lastly, the interaction between low parental knowledge and antisocial peer behavior predicting drunkenness was significant (Figure 4b). Specifically, the association between low parental knowledge and drunkenness was significantly weaker for adolescents with higher versus lower antisocial peer behavior from ages 12.4 to 18.1.

Figure 4a.

Age-varying associations of low parental knowledge and antisocial peer behavior with past-month drunkenness (Nperson = 7928, Nobs = 36283).

Figure 4b.

Age-varying association between low parental knowledge and past-month drunkenness as a function of antisocial peer behavior. Box indicates age range (12.4 to 18.1) of significant moderation (Nperson = 7928, Nobs = 36283).

Finally, the age-varying associations between interpersonal risk factors and adolescents’ past-month marijuana use were examined (Figure 5a). Low parental knowledge had a significant association with marijuana use across all ages, with the strongest association at age 11 (OR = 2.89; 95% CIs [1.97, 4.23]). This association decreased rapidly from ages 11 to 14 and maintained a small but significant association through age 18.9. Antisocial peer behavior was significantly associated with marijuana use at all ages and exhibited a curvilinear trend. The magnitude of association increased rapidly from age 11 (OR = 1.49; 95% CIs [1.00, 2.22]) to age 13.8 (OR = 2.60; 95% CIs [2.40, 2.81]), followed by a gradual decline until age 17.4 (OR = 2.14; 95% CIs [2.01, 2.27]) and then another increase through age 18.9 (OR = 2.40; 95% CIs [1.99, 2.89]). Finally, the association between low parental knowledge and marijuana use differed significantly as a function of antisocial peer behavior (Figure 5b). Specifically, the association between low parental knowledge and marijuana use was significantly weaker for adolescents with higher versus lower antisocial peer behavior from ages 13.6 to 17.1.

Figure 5a.

Age-varying associations of low parental knowledge and antisocial peer behavior with past-month marijuana use (Nperson = 7923, Nobs = 36249).

Figure 5b.

Age-varying association between low parental knowledge and past-month marijuana use as a function of antisocial peer behavior. Box indicates age range (13.6 to 17.1) of significant moderation (Nperson = 7923, Nobs = 36249).

In summary, low parental knowledge and antisocial peer behavior were positively associated with adolescents’ past-month cigarette use, drunkenness, and marijuana use across majority of adolescence. The strength of associations between these interpersonal risk factors and substance use decreased across age, except between antisocial peer behavior and marijuana use, which showed a curvilinear trend across age. Across all three substances, low parental knowledge was more associated with substance use when antisocial peer behavior was lower than when it was higher. This dynamic interaction was significant across majority of adolescence.

Discussion

Our findings suggest that both low parental knowledge and antisocial peer behavior, despite showing declining associations with substance use across age, are robust risk factors for substance use across adolescence. The decline in the magnitude of associations could be due to individuals’ increasing exposure to various influences outside the family as well as individuals becoming more autonomous in their behaviors. For example, as adolescents get older, individuals’ substance use behaviors could be influenced by a wider range of influences, including those from peers and romantic partners (Cleveland et al., 2008; Fleming, White, Oesterle, Haggerty, & Catalano, 2010). Moreover, as they get more emotionally and socially mature, their substance use behaviors may be increasingly influenced by their own beliefs and values. Therefore, across adolescence, individuals’ decision to engage or not to engage in substance use may be less influenced by parental knowledge per se. Moreover, as adolescents get older, they are better at holding secrets and hiding misbehaviors from their parents, especially when they are affiliated with antisocial peers (Tilton-Weaver, 2014). Even if parents generally know where they are, who they are with, and some of their activities, parents are unlikely to know the full details of their behaviors (e.g., substance use behaviors) because parents are not spending as much time in person with their adolescents and adolescents engage in more activities and have greater mobility. There is also decline in the level of parental knowledge across age, which could be due to adolescents striving for increasing autonomy and parents granting increasing autonomy to their adolescents. While the decline in the level of parental knowledge is likely a contributing factor of increasing adolescent substance use across age, the magnitude of association between parental knowledge and substance use however also decreases. This suggests in light of decreasing protective benefits of parental knowledge over adolescence, other factors, such as relationship quality, may emerge as protective factors over the course of adolescence (Van Ryzin et al., 2012).

Antisocial peer behavior was another robust risk factor for substance use across adolescence, even when accounting for the effect of parental knowledge. The association between antisocial peer behavior and adolescent substance use is likely due to both selection and socialization processes. Specifically, adolescents who engage in problem behaviors, including antisocial behaviors and substance use, are likely to seek friends who also engage in these behaviors and these friends then also encourage more problem behaviors including substance use (Osgood et al., 2013; Schulenberg et al., 1999; Simons-Morton & Chen, 2006). The decline in association between antisocial peer behavior and substance use (i.e., cigarette use and drunkenness) across age might indicate individuals’ behaviors are less likely to be influenced by their peers, which may be due to individuals’ improvements in resistance to peer pressure on substance use (Steinberg & Monahan, 2007). This decoupling of antisocial peer behavior and adolescents’ substance use could be indicative of increasing behavioral autonomy over time. Another possible explanation is that as substance use becomes more prevalent across adolescence, early substance use is considered “more deviant” than later use. Therefore, later in adolescence, individuals could use substances with peers who do not necessarily engage in antisocial behaviors. In addition, the levels of antisocial peer behavior, on average, increased from age 11 to age 15 and then remained stable in this sample. This may imply that there are relatively few early adolescents engaging in antisocial behaviors and the affiliation with these peers may imply active seeking of these peers and therefore, it is more likely that these adolescents engage in substance use together. However, as the prevalence of antisocial peer behavior increases across adolescence, there may simply be a higher likelihood that any adolescent has peers who engage in antisocial behaviors rather than adolescents actively seeking these peers, therefore the association between antisocial peer behavior and substance use may be weaker in middle and late adolescence. Nevertheless, the decline in the strength of the association between antisocial peer behavior and substance use was not found for marijuana use. This may be because marijuana use was illicit at the time and place of data collection and the prevalence of marijuana use in adolescence is generally lower than other substances. Therefore, getting access to marijuana through social and commercial sources is more difficult and the affiliation with antisocial peers may be an important way to access the substance.

Antisocial peer behavior appears to have a stronger association with substance use than low parental knowledge. However, it is important to note that although standardization was used to compare effects, interpretations of which is larger should be made with caution because no inferential statistical test was performed. Our particular method of standardization (using an age-invariant estimate of the standard deviation) was chosen to facilitate metric consistency across age. Our finding that antisocial peer behavior had a stronger association is consistent with existing research showing that peers are more influential in the area of substance use than parents (Allen, Donohue, Griffin, Ryan, & Turner, 2003; Kandel, 1985; Schuler et al., 2019). As adolescent substance use occurs predominantly with peers and peers are the most common providers of substances (Harrison, Fulkerson, & Park, 2000), antisocial peer behavior was likely to have a stronger association with substance use than low parental knowledge. Nevertheless, it should be noted that parents can influence adolescents’ choice of peers (Mounts, 2001; Tilton-Weaver, Burk, Kerr, & Stattin, 2013).

This study provides evidence that parental knowledge may have been more effective in preventing substance use when antisocial peer behavior was low than when it was high. Not only that antisocial peer affiliation is likely to decrease the level of parental knowledge (Kerr & Stattin, 2003; Laird, Pettit, Bates, & Dodge, 2003), this suggests that when adolescents are associated with peers with more antisocial behaviors, parents knowing their adolescents’ whereabouts and activities is not as effective in preventing adolescent substance use as when antisocial peer behavior was low. However, it is important to note that low parental knowledge was still significantly associated with substance use even when the levels of antisocial peer behavior were high. This suggests that parental knowledge matters, albeit to varying extent, across different levels of antisocial peer behavior, which is consistent with existing evidence (Shillington et al., 2005). However, parental knowledge may be more effective in preventing substance use where antisocial peer groups are not well-established (i.e., when antisocial peer behavior is low), but less effective in situations where adolescents have an established antisocial peer group. This finding may shed light on why in the presence of high levels of antisocial peers, some parents may relinquish their involvement (Dishion et al., 2004). Although parental knowledge appears to be less effective when antisocial peer behavior was high, parental knowledge may reduce the affiliation with antisocial peers (e.g., Van Ryzin et al., 2010; Svensson, 2003). One thing to note is that these previous studies are based on non-U.S. samples and those based on U.S. samples shows no evidence of interaction (Trucco et al., 2011; Wood et al., 2004). Therefore, replication of these findings with U.S. samples is needed.

The current findings offer insights into the developmental timing and targets for family- and school-based interventions during adolescence. There is considerable evidence that early initiation of substance use is harmful, and early family-based intervention has shown promise in reducing adolescent substance use (Spoth et al., 2013). Our findings have shown that the strength of associations of parental knowledge and antisocial peer behavior with substance use is not constant but is strongest in early adolescence. Together, this suggests that early adolescence may be a particularly fruitful period for substance use interventions targeting these parent and peer risk factors. Therefore, family-based prevention and interventions aim at reducing early use could focus on teaching parents how to maintain high warmth and monitoring in their parenting practices during early adolescent years. Evidence shows that children who are close to their parents are more likely to disclose their activities to parents, thus enhancing parental knowledge (Vieno, Nation, Pastore, & Santinello, 2009; Yau, Tasopoulos-Chan, & Smetana, 2009). Furthermore, enhancing parental knowledge before adolescents are affiliated with antisocial peers may be particularly protective, although it is also important for parents not to relinquish monitoring in face of adolescents’ antisocial peers because parental knowledge still matters even when the level of antisocial peer is high.

Regarding current peer-focused interventions, effectiveness is generally modest and past research has cautioned about possible iatrogenic effects of interventions among high-risk youth (Dishion et al., 1999; Mahoney, Stattin, & Lord, 2004). The current findings suggest that early adolescence is a critical period for school-based interventions targeting the reduction of antisocial peer behavior. In order to do so without encouraging antisocial peers to further reinforce each other’s substance use, it may be more effective to target reducing antisocial behaviors, increasing peer acceptance, and improving school climate so as to prevent adolescents from forming antisocial groups in the first place. Another major implication for intervention is that despite the declining associations between these risk factors and substance use across adolescence, they remain important risk factors across the developmental period. This suggests that interventions may be particularly effective in early adolescence, but sustained intervention efforts across the middle and high school years are critical for reducing adolescent substance use.

There are several limitations in the present study that should be addressed in future research. First, in our application of TVEM, the age-varying estimates we present is a blend of between- and within-person information, and thus should not be interpreted as representing the mean of individuals’ change trajectories over time but rather as age trends in the population. Second, as with more traditional regression analysis, the coefficient functions estimated in this study represent associations and should not be interpreted as causal effects. Third, the current sample was primarily white and rural and therefore, results are not aimed to be generalized to the national population. Fourth, all the constructs measured in the present study were adolescent report, which may have inflated the associations due to shared-method variance. Finally, our measure of antisocial peer behaviors is somewhat limited in scope that it only focuses on friendships. Future work may consider whether antisocial peers and antisocial friends may differentially influence adolescent substance use.

The present study examined the developmentally sensitive age-varying associations between interpersonal risk factors (i.e., low parental knowledge and antisocial peer behavior) and adolescent substance use. This study has several strengths. First, our findings enhance our understanding on how the associations between interpersonal risk factors and adolescent substance use vary across continuous age. The use of TVEM allows for flexible estimation of the shape of the association across age, thus capturing a more nuanced perspective of age-varying associations. Second, the age-varying associations between one risk factor (e.g., parental knowledge) and substance use behaviors were estimated controlling for the other risk factor (e.g., antisocial peer behavior) as well as covariates indicating gender, race, economic disadvantage, and family structure. Finally, the present study relied on a relatively large sample of adolescents with adequate spread on age over the course of adolescence to allow for a careful examination of age-varying associations.

This study makes important contribution to the area of interpersonal risk factors for adolescent substance use by providing a developmentally sensitive perspective on such associations. The findings suggest potential timing and targets of risk factors for more effective prevention and interventions for adolescent substance use. Our findings support the view that parents and peers are two important socialization agents related to substance use across adolescence and early intervention designed to address parent and peer risk factors are likely to be more effective at reducing onset or early substance use.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement:

The original PROSPER project was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01 DA013709) and co-funding from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. This project was supported by awards (P50 DA039838, T32 DA017629, and R01 DA039854) from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

This manuscript is based on part of the first author’s doctoral dissertation.

References

- Allen M, Donohue WA, Griffin A, Ryan D, & Turner MMM (2003). Comparing the influence of parents and peers on the choice to use drugs: A meta-analytic summary of the literature. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 30, 163–186. 10.1177/0093854802251002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ary DV, Duncan TE, Biglan A, Metzler CW, Noell JW, & Smolkowski K (1999). Development of adolescent problem behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 27, 141–150. 10.1023/A:1021963531607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahr SJ, Hoffmann JP, & Yang X (2005). Parental and peer influences on the risk of adolescent drug use. Journal of Primary Prevention, 26, 529–551. 10.1007/s10935-005-0014-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes GM, Hoffman JH, Welte JW, Farrell MP, & Dintcheff BA (2006). Effects of parental monitoring and peer deviance on substance use and delinquency. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68, 1084–1104. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00315.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester D, & Furman W (1987). The development of companionship and intimacy. Child Development, 58, 1101–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Hussong A, & Beltran I (2009). Adolescent substance use. In Lerner RM & Steinberg L (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology, Vol 1: Individual bases of adolescent development (3rd ed., pp. 723–763). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland MJ, Feinberg ME, Bontempo DE, & Greenberg MT (2008). The role of risk and protective factors in substance use across adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Health, 43, 157–164. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.01.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, & Steinberg L (2008). Adolescent development in interpersonal context In Damon W & Lerner RM (Eds.), Child and adolescent development: An advanced course (pp. 551–590). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD (1989). Iowa Youth and Families Project, Wave A. Report prepared for Iowa State University. Ames, IA: Institute for Social and Behavioral Research. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, McCord J, & Poulin F (1999). When interventions harm: Peer groups and problem behavior. American Psychologist, 54, 755–764. 10.1037/0003-066X.54.9.755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Nelson SE, & Bullock BM (2004). Premature adolescent autonomy: Parent disengagement and deviant peer process in the amplification of problem behaviour. Journal of Adolescence, 27, 515–530. https://doi.org/10.1016Zj.adolescence.2004.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Poulin F, & Medici SN (2000). The ecology of premature autonomy in adolescence: Biological and social influences In Kerns KA, Contreras JM, & Neal-Barnett AM (Eds.), Family and peers: Linking two social worlds (pp. 27–45). Westport, CT: Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein M, Hill KG, Roe SS, Bailey JA, Iacono WG, McGue M, ... Haggerty KP (2017). Time-varying effects of families and peers on adolescent marijuana use: Personenvironment interactions across development. Development and Psychopathology, 29, 887–900. 10.1017/S0954579416000559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Swain-Campbell NR, & Horwood LJ (2002). Deviant peer affiliations, crime and substance use: A fixed effects regression analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 30, 419–430. 10.1023/A:1015774125952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming CB, White HR, Oesterle S, Haggerty KP, & Catalano RF (2010). Romantic relationship status changes and substance use among 18- to 20-year-olds. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 71, 847–856. 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fosco GM, & LoBraico EJ (2018). A family systems framework for adolescent antisocial behavior: The state of the science and suggestions for the future In Fiese BH, Celano M, Deater-Deckard KD, Jouriles EN, & Whisman MA (Eds.), APA handbook of contemporary family psychology: Applications and broad impact of family psychology (pp. 53–68). Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Fosco GM, & LoBraico EJ (2019). Elaborating on premature adolescent autonomy: Linking variation in daily family processes to developmental risk. Development and Psychopathology, 1–15. Advance online publication. 10.1017/s0954579419001032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, & Dawson DA (1997). Age at onset of alcohol use and its association with DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: results from the national longitudinal alcohol epidemiologic survey. Journal of Substance Abuse, 9, 103–110. 10.1016/S0899-3289(97)90009-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison PA, Fulkerson JA, & Park E (2000). The relative importance of social versus commercial sources in youth access to tobacco, alcohol, and other drugs. Preventive Medicine, 31, 39–48. 10.1006/pmed.2000.0691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson R, Heeren T, Winter MR, & Wechsler H (2003). Early age of first drunkenness as a factor in college students’ unplanned and unprotected sex attributable to drinking. Pediatrics, 111, 34–41. 10.1542/peds.111.1.34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R (1991). Risk behavior in adolescence: A psychosocial framework for understanding and action. Journal of Adolescent Health, 2, 53–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R, & Jessor SL (1977). Problem behavior and psychosocial development: A longitudinal study of youth. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, Miech RA, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, & Patrick ME (2018). Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2017: Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB (1985). On processes of peer influences in adolescent drug use: A developmental perspective. Advances in Alcohol & Substance Abuse, 4, 139–162. 10.1300/J251v04n03_07 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, & Jessor R (2002). The gateway hypothesis revisited In Kandel DB (Ed.), Stages and pathways of drug involvement: Examining the gateway hypothesis (pp. 365–372). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr M, & Stattin H (2000). What parents know, how they know it, and several forms of adolescent adjustment: further support for a reinterpretation of monitoring. Developmental Psychology, 36, 366–380. 10.1037/0012-1649.36.3.366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr M, & Stattin H (2003). Parenting of adolescents: Action or reaction? In Crouter AC & Booth A (Eds.), Children’s influence on family dynamics: The neglected side of family relationships (pp. 121–151). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Kiesner J, Poulin F, & Dishion TJ (2010). Adolescent substance use with friends: Moderating and mediating effects of parental monitoring and peer activity contexts. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 56, 529–556. 10.1353/mpq.2010.0002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Rossow I, Simons-Morton B, Bogt T. Ter, Kokkevi A, & Godeau E (2013). Not early drinking but early drunkenness is a risk factor for problem behaviors among adolescents from 38 European and North American countries. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 37, 308–314. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01895.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird RD, Pettit GS, Bates JE, & Dodge K. a. (2003). Parent’s monitoring relevant knowledge and adolescents’ delinquant behavior: Evidence of correlated developmental changes and reciprocal influences. Child Development, 74, 752–768. 10.1055/s-0029-1237430.Imprinting [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza ST, & Vasilenko SA (2015). New methods shed light on age of onset as a risk factor for nicotine dependence. Addictive Behaviors, 50, 161–164. https://doi.org/10.1016Zj.addbeh.2015.06.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza ST, Vasilenko SA, & Russell MA (2016). Time-varying effect modeling to address new questions in behavioral research: Examples in marijuana use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 30, 939–954. 10.1037/adb0000208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R, Dziak JJ, Huang L, Wagner AT, & Yang J (2017). TVEM (time-varying effect model) SAS macro users’ guide (Version 3.1.1). Retrieved from http://methodlogy.psu.edu [Google Scholar]

- Lintonen T, Rimpelä M, Vikat A, & Rimpelä A (2000). The effect of societal changes on drunkenness trends in early adolescence. Health Education Research, 15, 261–269. 10.1093/her/15.3.261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippold MA, Coffman DL, & Greenberg MT (2014). Investigating the potential causal relationship between parental knowledge and youth risky behavior: A propensity score analysis. Prevention Science, 15, 869–878. 10.1007/s11121-013-0443-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippold MA, Fosco GM, Ram N, & Feinberg ME (2016). Knowledge lability: Within-person changes in parental knowledge and their associations with adolescent problem behavior. Prevention Science, 17, 274–283. 10.1007/s11121-015-0604-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lydon-Staley DM, & Geier CF (2018). Age-varying associations between cigarette smoking, sensation seeking, and impulse control through adolescence and young adulthood. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 28, 1–14. 10.1111/jora.12335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney JL, Stattin H, & Lord H (2004). Unstructured youth recreation centre participation and antisocial behaviour development: Selection influences and the moderating role of antisocial peers. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 28, 553–560. 10.1080/01650250444000270 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mounts NS (2001). Young adolescents’ perceptions of parental management of peer relationships. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 21, 92–122. 10.1177/0272431601021001005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Odgers CL, Caspi A, Nagin DS, Piquero AR, Slutske WS, Milne BJ, ... Moffitt TE (2008). Is it important to prevent early exposure to drugs and alcohol among adolescents? Psychological Science, 19, 1037–1044. 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02196.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osgood DW, Feinberg ME, Gest SD, Moody J, Ragan DT, Spoth R, ... Redmond C (2013). Effects of PROSPER on the influence potential of prosocial versus antisocial youth in adolescent friendship networks. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53, 174–179. 10.1016/jjadohealth.2013.02.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Debaryshe B, & Ramsey E (1989). A developmental perspective on antisocial behavior. American Psychologist, 44, 329–335. 10.1037/0003-066X.44.2.329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racz SJ, & McMahon RJ (2011). The relationship between parental knowledge and monitoring and child and adolescent conduct problems: A 10-year update. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 14, 377–398. 10.1007/s10567-011-0099-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rai AA, Stanton B, Wu Y, Li X, Galbraith J, Cottrell L, ... Burns J (2003). Relative influences of perceived parental monitoring and perceived peer involvement on adolescent risk behaviors: an analysis of six cross-sectional data sets. The Journal of Adolescent Health : Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 33(2), 108–118. 10.1016/S1054-139X(03)00179-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redmond C, Spoth R, Shin C, & Lepper HS (1999). Modeling long-term parent outcomes of two universal family-focused preventive interventions: One-year follow-up results. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67, 975–984. 10.1037/0022-006X.67.6.975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ, Seifer R, & Bartko WT (1997). Environmental perspectives on adaptation during childhood and adolescence In Luthar SS & Burack JA (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology: Perspectivs on adjustment, risk, and disorder (pp. 507–526). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg J, Maggs JL, Dielman TE, Leech SL, Kloska D, Shope JT, & Laetz VB (1999). On peer influences to get drunk : A panel study of young adolescents. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 45, 108–142. [Google Scholar]

- Schuler MS, Tucker JS, Pedersen ER, & D’Amico EJ (2019). Relative influence of perceived peer and family substance use on adolescent alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use across middle and high school. Addictive Behaviors, 88, 99–105. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.08.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selya AS, Dierker L, Rose JS, Hedeker D, & Mermelstein RJ (2016). Early-emerging nicotine dependence has lasting and time-varying effects on adolescent smoking behavior. Prevention Science, 17, 743–750. 10.1007/s11121-016-0673-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shillington AM, Lehman S, Clapp J, Hovell MF, Sipan C, & Blumberg EJ (2005). Parental monitoring: Can it continue to be protective among high-risk adolescents? Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse, 15, 1–15. 10.1300/j029v15n01_01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton B, & Chen RS (2006). Over time relationships between early adolescent and peer substance use. Addictive Behaviors, 31, 1211–1223. https://doi.org/10.1016Zj.addbeh.2005.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG, Campione-Barr N, & Metzger A (2006). Adolescent development in interpersonal and societal contexts. Annual Review of Psychology, 57, 255–284. 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, Greenberg M, Bierman K, & Redmond C (2004). PROSPER community-university partnership model for public education systems: Capacity-building for evidence-based, competence-building prevention. Prevention Science, 5, 31–39. 10.1023/B:PREV.0000013979.52796.8b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, Trudeau L, Shin C, Ralston E, Redmond C, Greenberg M, & Feinberg M (2013). Longitudinal effects of universal preventive intervention on prescription drug misuse: Three randomized controlled trials with late adolescents and young adults. American Journal of Public Health, 103, 665–672. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stattin H, & Kerr M (2000). Parental monitoring: a reinterpretation. Child Development, 71, 1072–1085. 10.2307/1132345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, & Monahan KC (2007). Age differences in resistance to peer influence. Developmental Psychology, 43, 1531–1543. 10.1037/0012-1649.43.6.1531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson R (2003). Gender differences in adolescent drug use. Youth & Society, 34, 300–329. 10.1177/0044118X02250095 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tan X, Shiyko MP, Li R, Li Y, & Dierker L (2012). A time-varying effect model for intensive longitudinal data. Psychological Methods, 17, 61–77. 10.1037/a0025814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilton-Weaver LC (2014). Adolescents’ information management: Comparing ideas about why adolescents disclose to or keep secrets from their parents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43, 803–813. 10.1007/s10964-013-0008-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilton-Weaver LC, Burk WJ, Kerr M, & Stattin H (2013). Can parental monitoring and peer management reduce the selection or influence of delinquent peers? Testing the question using a dynamic social network approach. Developmental Psychology, 49, 2057–2070. 10.1037/a0031854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trucco EM, Colder CR, & Wieczorek WF (2011). Vulnerability to peer influence: A moderated mediation study of early adolescent alcohol use initiation. Addictive Behaviors, 36, 729–736. https://doi.org/10.1016Zj.addbeh.2011.02.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ryzin MJ, Fosco GM, & Dishion TJ (2012). Family and peer predictors of substance use from early adolescence to early adulthood: An 11-year prospective analysis. Addictive Behaviors, 37, 1314–1324. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.06.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieno A, Nation M, Pastore M, & Santinello M (2009). Parenting and antisocial behavior: A model of the relationship between adolescent self-disclosure, parental closeness, parental control, and adolescent antisocial behavior. Developmental Psychology, 45, 1509–1519. 10.1037/a0016929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood MD, Read JP, Mitchell RE, & Brand NH (2004). Do parents still matter? Parent and peer influences on alcohol involvement among recent high school graduates. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 18, 19–30. 10.1037/0893-164X.18.L19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray-Lake L, Crouter AC, & McHale SM (2010). Developmental patterns in decision-making autonomy across middle childhood and adolescence: European American parents’ perspectives. Child Development, 81, 636–651. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01420.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yau JP, Tasopoulos-Chan M, & Smetana JG (2009). Disclosure to parents about everyday activities among American adolescents from Mexican, Chinese, and European backgrounds. Child Development, 80, 1481–1498. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01346.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young SE, Corley RP, Stallings MC, Rhee SH, Crowley TJ, & Hewitt JK (2002). Substance use, abuse and dependence in adolescence: prevalence, symptom profiles and correlates. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 68, 309–322. 10.1016/S0376-8716(02)00225-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.