Abstract

Objective:

Studies suggest lateral wall (LW) scala tympani (ST) height decreases apically, which may limit insertion depth. No studies have investigated the relationship of LW ST height with translocation rate or location.

Study Design:

Retrospective review

Setting:

Cochlear implant program at tertiary referral center

Subjects and Methods:

LW ST height was measured in preoperative images for patients with straight electrodes. Scalar location, angle of insertion depth (AID), and translocation depth were measured in postoperative images. Audiologic outcomes were tracked.

Results:

177 ears were identified with 39 translocations (22%). Median AID was 443° (interquartile range [IQ]: 367–550°). Audiologic outcomes (126 ears) showed a small, significant correlation between consonant-nucleus-consonant (CNC) word score and AID (r=0.20, p=0.027), though correlation was insignificant if translocation occurred (r=0.11, p=0.553). Translocation did not impact CNC score (p=0.335). AID was higher for translocated electrodes (503° vs. 445°, p=0.004). Median translocation depth was 381° (IQ: 222–399°). Median depth at which a 0.5mm electrode would not fit within 0.1mm of LW was 585° (IQ: 405–585°). Median depth at which a 0.5mm electrode would displace the basilar membrane by ≥0.1mm was 585° (IQ: 518–765°); this was defined as predicted translocation depth (PTD). Translocation rate was 39% for insertions deeper than PTD and 14% for insertions shallower than PTD (p=0.008).

Conclusion:

AID and CNC are directly correlated for straight electrodes when not translocated. Translocations generally occur around 380° and are more common with deeper insertions due to decreasing LW ST height. Risk of translocation increases significantly after 580°.

Keywords: Cochlear implantation, scala tympani height, translocation, straight electrodes

Introduction

Electrode arrays for cochlear implantation (CI) may be either precurved or straight. Precurved electrodes have memory, are designed to hug the modiolar wall, and are often referred to as “perimodiolar”. Straight electrodes are typically less rigid, assume the cochlea’s shape, and are often referred to as “lateral wall”. However, precurved electrodes often do not assume a perimodiolar position1 and straight electrodes do not always sit against the lateral wall (LW). Thus, in this paper, we will use the terms “precurved” and “straight”.

The optimal insertion depth for straight electrodes remains an area of active investigation. As demonstrated by Hardy in 1938, cochlear duct length is highly variable, ranging from 25–35mm in her analysis2 and up to 45mm in later analyses3,4. Therefore, an electrode of fixed length covers a variable portion of the cochlea. Shallow insertions minimize intracochlear trauma, thereby maximizing chances of hearing preservation5,6. However, shallow insertions reduce the electrode’s coverage of the cochlear duct, resulting in a limited range of neural stimulation and greater place-pitch mismatch7,8. Rivas et al. previously reported a cohort of 16 subjects and showed a direct correlation between angular insertion depth (AID) and consonant-nucleus-consonant (CNC) scores that reached a plateau after approximately 450° of AID9. O’Connell et al. recently investigated the relationship between AID and CNC score in a larger cohort of 48 ears implanted with straight electrode arrays and again found a direct correlation between AID and CNC score in the CI-only condition, though deeper insertions were associated with worse hearing preservation10. This agrees with work by Helbig et al. showing that AID was correlated with speech test scores in the electric-only condition.11 Of note, prior work has not addressed the relationship between AID and scalar translocation. Furthermore, in prior studies reported by our group, scalar location was determined manually by the surgeon after automated electrode localization. This process is now automated and more uniform12–14.

Scalar translocation is more common with precurved than straight electrodes15,16. Previous studies have reported translocation rates of up to 42% for precurved arrays17 and 5–11% for straight arrays16,17. Translocation has been shown to induce intracochlear trauma18 and result in poorer hearing preservation. Identification of factors that predispose to translocation may help surgeons avoid translocation and thereby improve hearing preservation and hearing outcomes.

One such factor may be scala tympani (ST) size. Early studies of ST anatomy showed that ST height is inversely proportional to distance from the round window19. Subsequent studies measured cross-sectional ST area, which was also shown to decrease along the cochlear duct20. Ketterer et al. recently investigated the hypothesis that smaller cochlear size is correlated with translocation from ST to scala vestibuli (SV), but this trend did not reach statistical significance21. However, their study made only a broad estimate of cochlear size and did not directly address ST size.

An interesting investigation by Avci et al. measured ST height and differentiated height based on horizontal position within the ST22. The conclusion was that ST height at the modiolus is essentially constant along the cochlear duct. However, ST height at the LW decreases significantly beyond 450° of angular depth.

We hypothesized that LW ST height limits the insertion depth of a straight electrode. Beyond a certain point, the electrode will no longer fit against the LW, and this may predispose to intracochlear trauma including translocation or basilar membrane (BM) displacement. We aimed to delineate ST anatomy, identify where translocations occur, and examine hearing outcomes after implantation of straight electrodes.

Methods

Imaging Analysis

IRB approval was obtained from the Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board (#090155) to consent patients undergoing CI to have post-insertion computerized tomography (CT) scanning either intraoperatively using mobile cone-beam CT (CBCT; Xoran XCAT) or postoperatively using either CBCT or traditional CT. Consent included explicit information regarding radiation exposure (CBCT radiation is approximately 1/5 that of traditional CT) and costs for CT scanning (covered by research funds and not billed to patient or insurance). From this database, preoperative and postoperative CT scans were reviewed to identify patients who underwent placement of a straight CI electrode. Only patients implanted at our institution were included. Charts were reviewed to record demographic information, operative information, and audiologic outcomes. CI electrode model was recorded for each implanted ear.

To detect if translocation had occurred, postoperative scans underwent intracochlear segmentation using previously published methods to visualize intracochlear anatomy and locate the intracochlear path of implanted electrodes12–14,23,24. AID, scalar location, and presence or absence of tip fold-over was recorded for each patient.

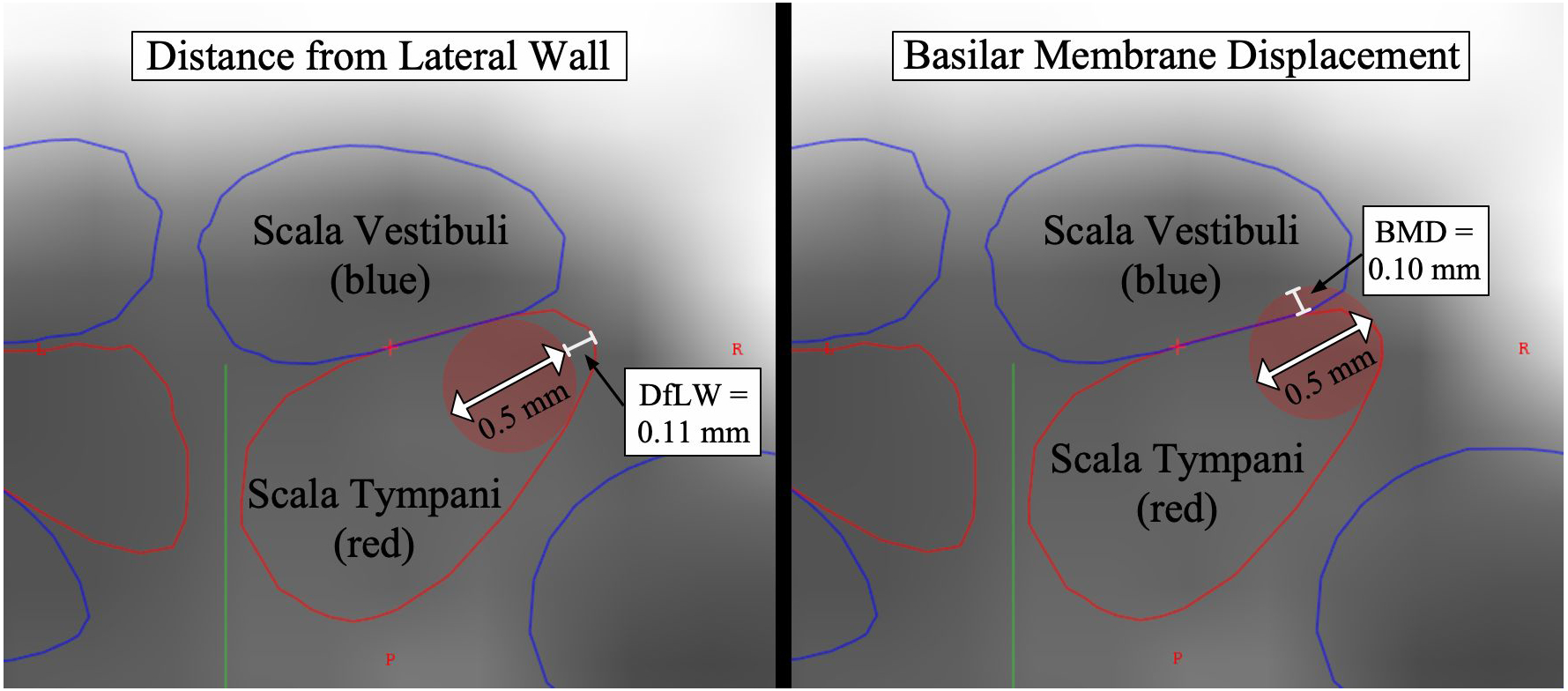

To provide more general information about ST height regardless of whether translocation had occurred, preoperative scans, when available, were analyzed using the same cochlear segmentation methods as the postoperative scans (above). Using custom, in-house software, the cochlea was visualized along a mid-modiolar axis to show ST and SV in cross-section. Two measurements were made every 45° from 0–900° of angular depth for each cochlea (Figure 1). For the first measurement (distance from lateral wall: DfLW), a circle with 0.5mm diameter was placed as laterally as possible while remaining within the ST borders. If this circle did not sit flush against the LW, the distance between this circle and the LW was recorded. For the second measurement (basilar membrane displacement: BMD), a circle with 0.5mm diameter was placed against the LW but allowed to overlap the BM. If the circle could not fit within the ST borders, the distance that it trespassed into the SV was measured. This approximated the extent to which an electrode sitting against the LW would have to displace the BM in order to remain in ST. For both of these measurements, diameter of 0.5mm was chosen as it represents the diameter of most straight electrode arrays at their apical tip.

Figure 1.

Scala tympani measurement tool. On left, distance from lateral wall is measured: red circle with diameter 0.5mm sits 0.11mm from lateral wall of scala tympani. On right, basilar membrane displacement is measured.

Hearing Outcomes

Audiologic outcomes were reviewed for all patients for whom these data were available. This data was collected prospectively as part of a separate, IRB-approved study. Pre-lingually deafened patients and pediatric patients were excluded from analysis of hearing outcomes. Additionally, patients with ipsilateral vestibular schwannoma or prior extensive otologic surgery (e.g. labyrinthectomy) were excluded from analysis of hearing outcomes.

Each participant underwent postoperative evaluation and programming according to Vanderbilt University Medical Center’s standard CI protocol as outlined below. Outcome data including residual acoustic hearing thresholds, CNC word scores25, AzBio sentence scores26, and Speech Spatial Qualities questionnaire data27 were prospectively collected.

Audiometric Thresholds

Pre and postoperative acoustic hearing thresholds were obtained in a double-walled sound-treated booth. To characterize hearing preservation, air conduction thresholds at 250 Hz were recorded preoperatively and 6–18 months postoperatively. (250 Hz was chosen because, when aided, it is the lowest frequency at which patients derive significant electric acoustic benefit on average28,29.)

Speech Recognition

Speech recognition testing was completed in a sound-treated booth with a presentation level of 60 dBA through a single loudspeaker positioned at 0° azimuth approximately one meter from the listener. To verify calibration, rooms were equipped with sound level meters positioned at the level of the patient’s head. Participants were instructed to repeat as much as possible and encouraged to guess when necessary. Participants completed CNC word recognition (50-word list)25 and AzBio sentence recognition (20-sentence list)26. Sentences were presented in quiet and +5 dB signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). Scores were recorded as percentage of words correctly repeated. Reporting of results followed the revised Minimum Speech Test Battery for adult CI recipients30.

Speech Spatial Qualities (SSQ)

The SSQ questionnaire assesses subjective hearing abilities across three listening domains: speech understanding, spatial hearing, and overall quality of speech using a visual analog scale ranging from 1 (poor) to 10 (perfect)27. The overall score (an average of these three subscales) was reported.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8.0.1 for Mac (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Continuous data were compared using unpaired t test (if two groups) or ANOVA test (if multiple groups) with follow-up Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Categorical data were compared using Fisher’s exact test (if two groups) or chi-squared test (if multiple groups).

Results

In total, 180 ears underwent CI with a straight electrode and had appropriate imaging available. Two electrodes were intentionally inserted into SV rather than ST and were therefore excluded. Only one Cochlear CI24RE(ST) electrode (Cochlear Limited, Sydney, Australia) was used and was excluded as no other insertions with this model were available for comparison. After excluding these three, 177 ears were analyzed. Models included Advanced Bionics (AB) 1J and AB SlimJ (Advanced Bionics, Sonova Holding AG, Stäfa, Switzerland); Cochlear CI422 and CI522 (considered together given that arrays are the same; only receiver stimulators differ); MED-EL Flex 24, MED-EL Flex 28, and MED-EL Standard (MED-EL, Innsbruck, Austria). Breakdown by CI electrode model was as follows: AB 1J: 28 (16%), AB SlimJ: 11 (6%), Cochlear CI422/522: 46 (26%), MED-EL Flex 24: 8 (5%), MED-EL Flex 28: 52 (29%), MED-EL Standard: 32 (18%).

Angular Insertion and Translocation Depths

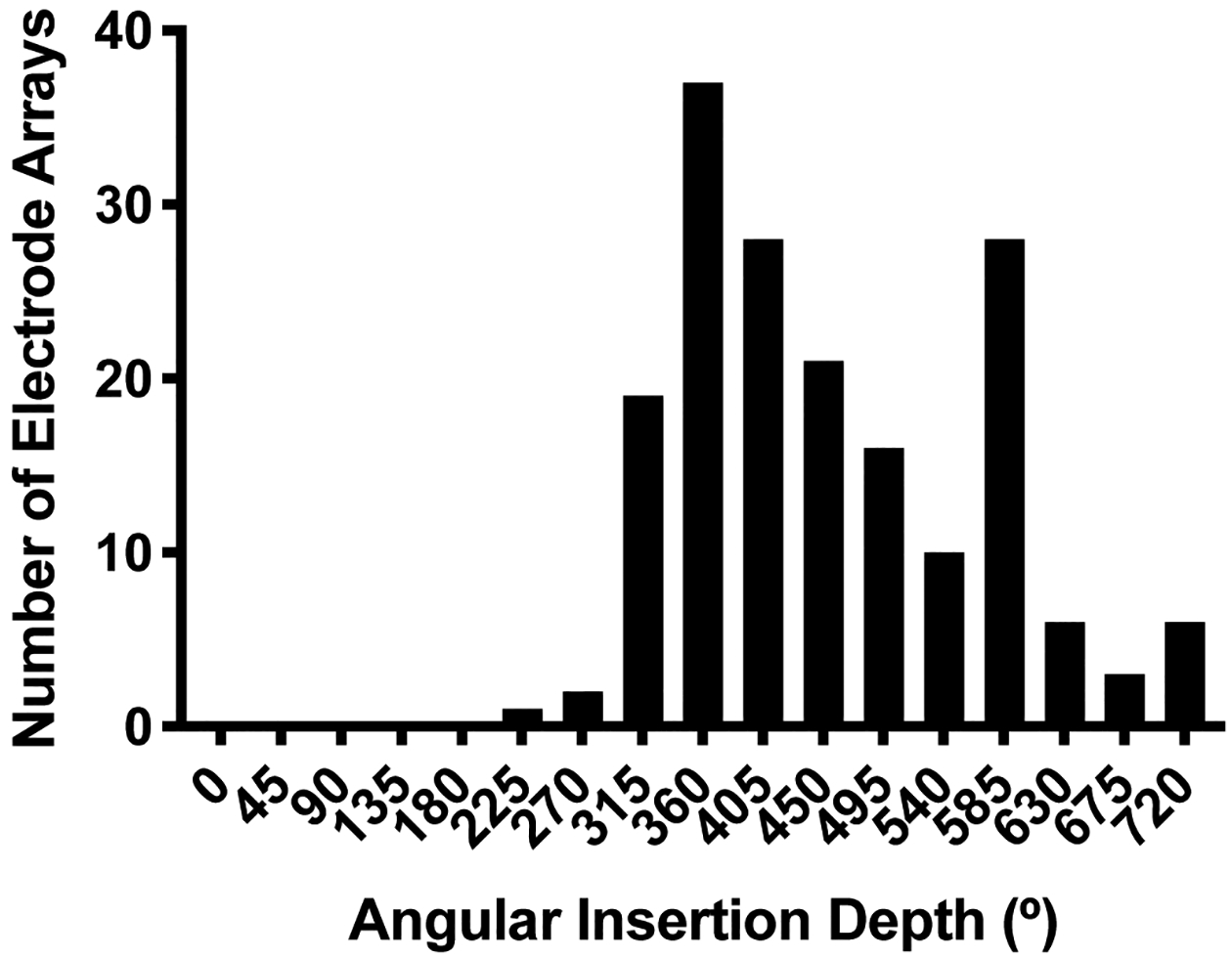

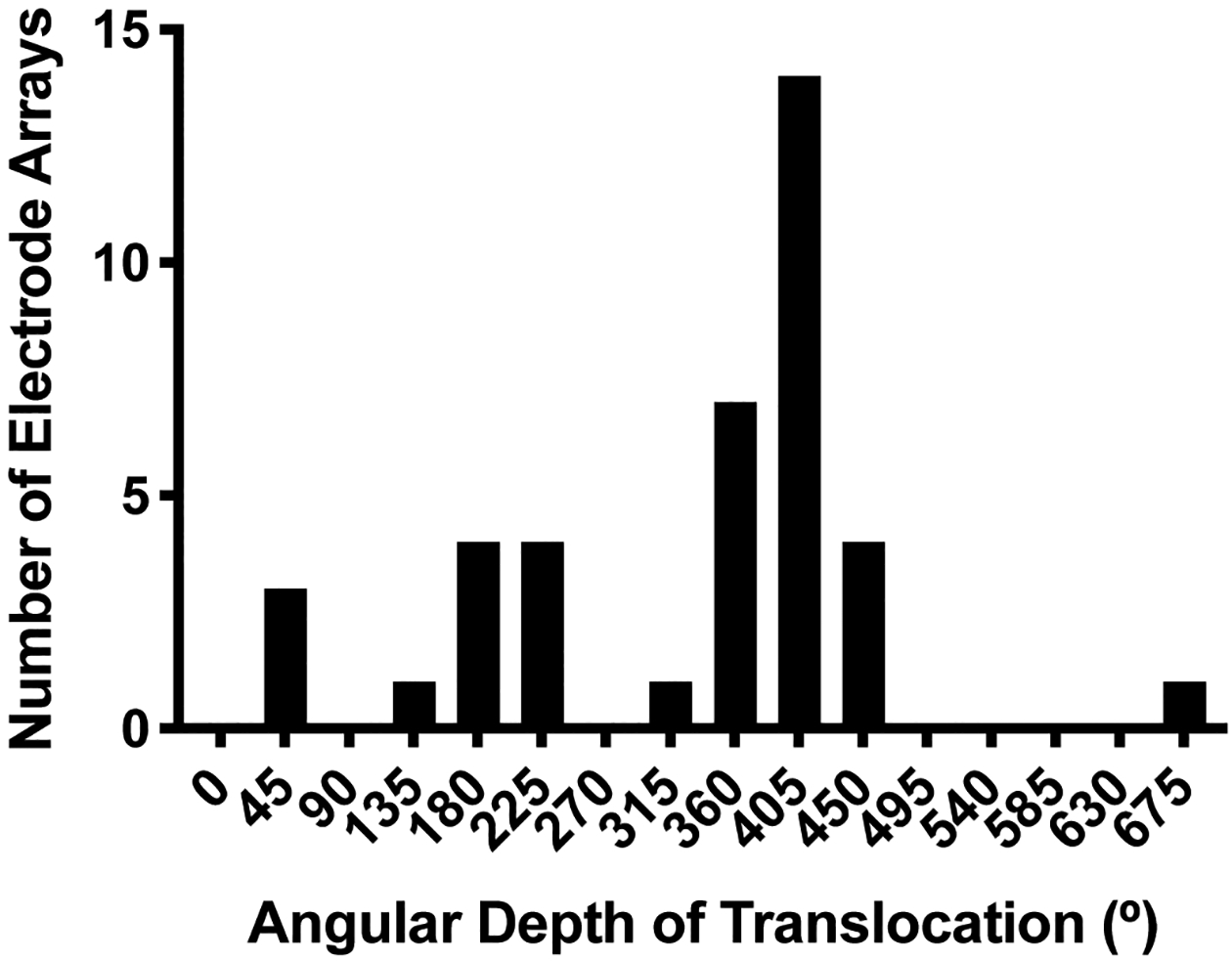

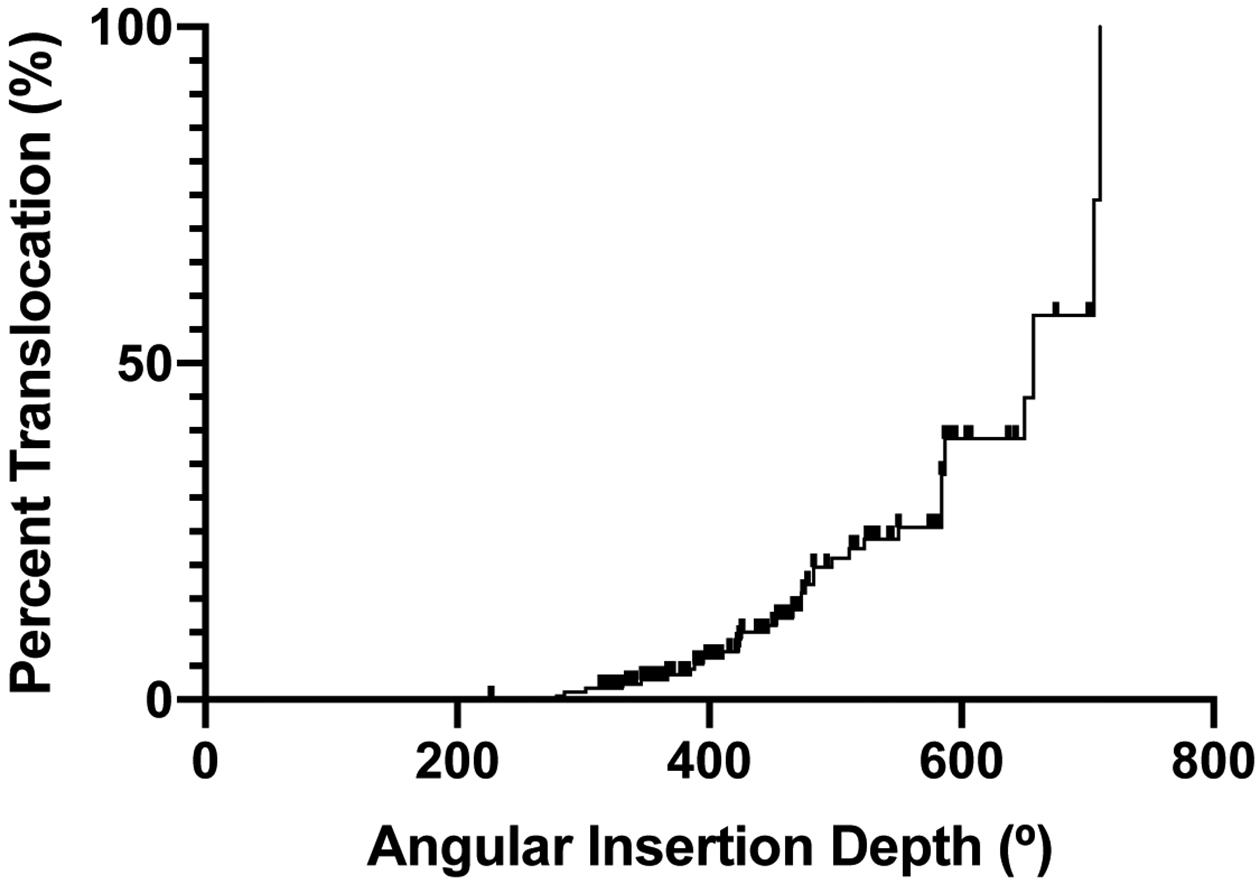

Overall, median AID was 443° (interquartile range [IQ]: 367–550°). A histogram demonstrating the distribution of AIDs is shown in Figure 2. Analysis of postoperative imaging showed that translocations occurred in 39 cases (22%). There was no significant difference in translocation rates among all electrode models when compared to one another with Fischer’s exact test. Median angular depth at which translocation occurred was 381° (IQ: 222–399°). As shown in Figure 3, there was a bimodal distribution of translocation depths with most occurring around 400° followed by a subset occurring around 200°. AID was higher for translocated electrodes compared to non-translocated electrodes (503° vs. 445°, p=0.004). Translocation became increasingly common at high AID; translocation occurred in 8 of 10 electrodes inserted to ≥650°. Translocation risk at a given AID was represented using an inverted Kaplan-Meier curve (Figure 4) where the X-axis is AID. At their final AID, electrodes were considered events if translocation occurred or censored if it did not. A sharp increase is seen at 584°, the AID of four translocated electrodes.

Figure 2.

Histogram of angular insertion depth for all electrode arrays. X-axis labels correspond to the center of bins with a width of 45°.

Figure 3.

Histogram of angular depth of translocation for translocated electrodes. X-axis labels correspond to the center of bins with a width of 45°.

Figure 4.

Risk of translocation at given angular insertion depth (AID) is represented using an inverted Kaplan-Meier curve. At their final AID, arrays were considered events if translocation occurred or censored if it did not.

Average AID for each CI model is summarized in Table 1. ANOVA testing showed that MED-EL Flex 28 and MED-EL Standard electrodes had deeper AIDs on average than all other models (p<0.001). Follow-up multiple comparisons testing showed that AID was not significantly different between these two models.

Table 1.

Angular insertion depth (AID) is shown for each electrode array model. ANOVA testing showed that Flex 28 and Standard electrodes had deeper AIDs on average than all other models (p<0.001). AID was not significantly different between these two models.

| Electrode Array Model | Mean Angular Insertion Depth | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|

| AB 1J | 357° | 333–380° |

| AB SlimJ | 411° | 376–445° |

| Cochlear CI422/522 | 399° | 380–418° |

| MED-EL Flex 24 | 420° | 387–453° |

| MED-EL Flex 28 | 528° * | 507–549° |

| MED-EL Standard | 543° * | 495–591° |

Scala Tympani Measurements

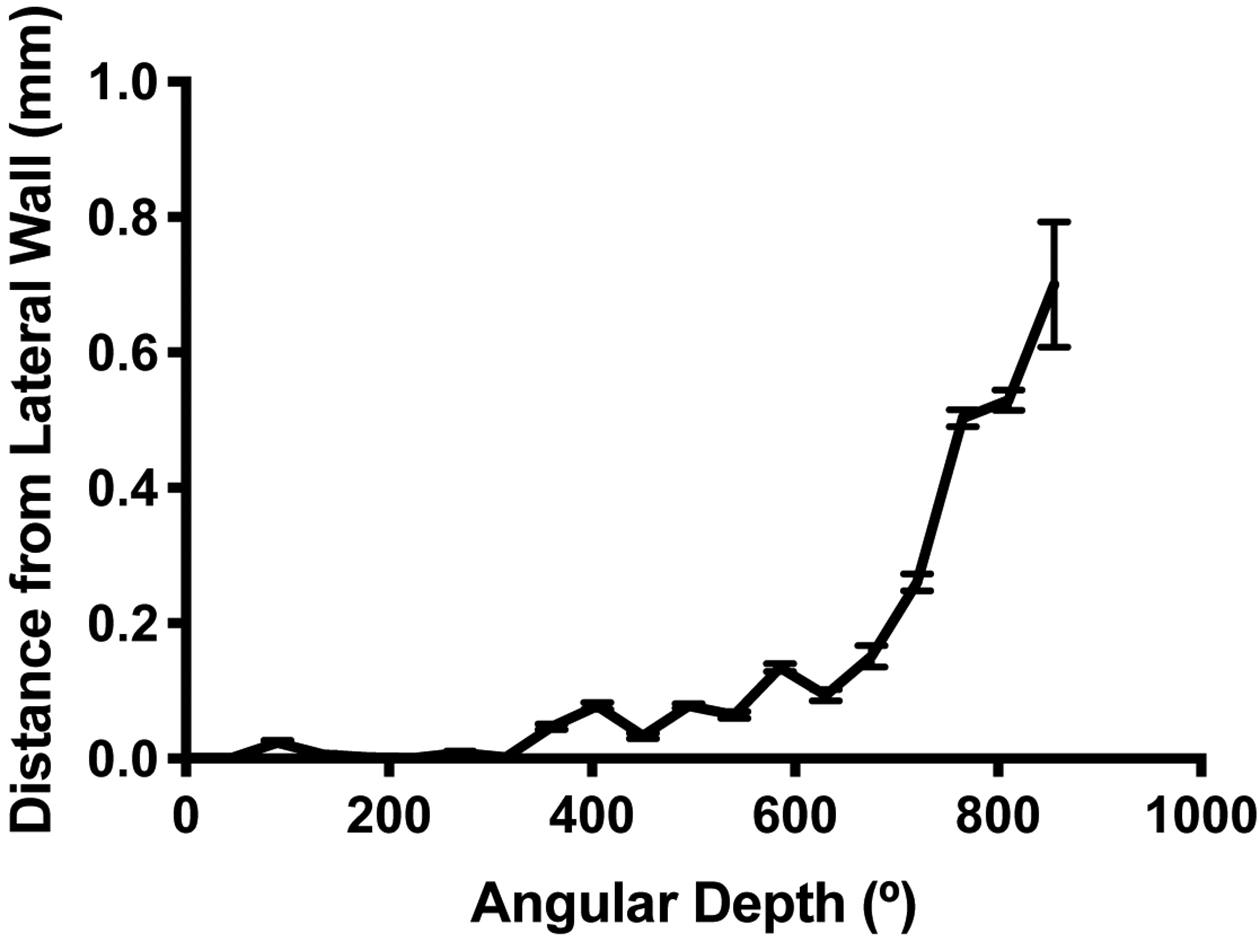

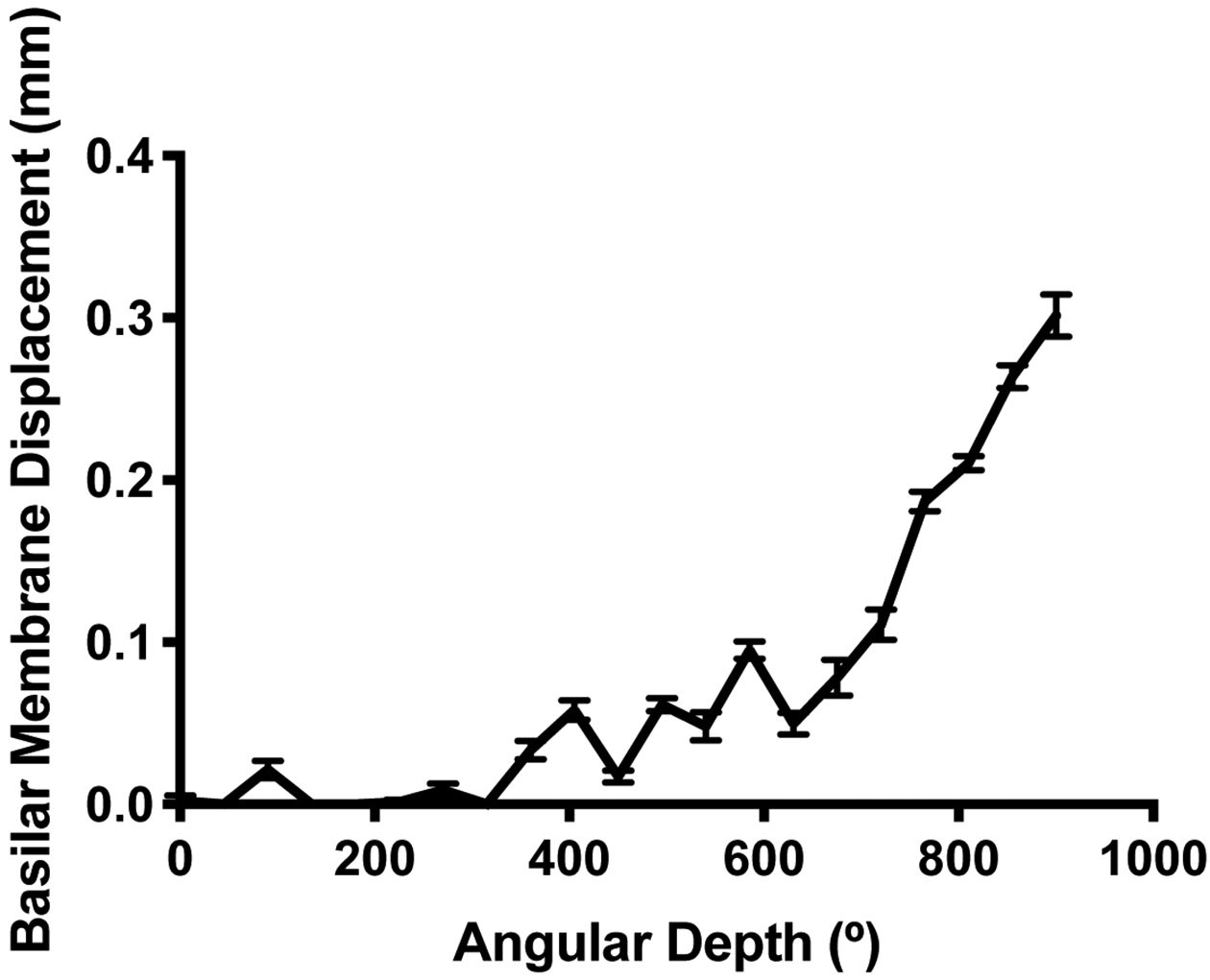

Scala tympani measurements (described above) were obtained in 129 ears from preoperative imaging. The median depth at which DfLW was ≥0.1mm was 585° (IQ: 405–585°). DfLW increased as angular depth increased (Figure 5). BMD also increased as angular depth increased (Figure 6). The median depth at which BMD was ≥0.1mm was 585° (IQ: 518–765°).

Figure 5.

Distance (in mm) from the lateral wall of the scala tympani where an electrode with diameter 0.5mm would sit.

Figure 6.

Basilar membrane displacement (in mm) caused by an electrode with diameter 0.5mm sitting against the lateral wall of the scala tympani.

The angular depth at which BMD ≥0.1mm was defined as the predicted translocation depth (PTD) for each cochlea. A cut-off of 0.1mm was chosen because this represents 20% of an average electrode’s apical diameter. It was hypothesized that electrodes inserted deeper than PTD would be at a greater risk for translocation. After excluding six electrodes that translocated prior to 200° of angular depth, the translocation rate was 39% (12 of 31) for electrodes inserted deeper than PTD and 14% (13 of 92) for electrodes inserted shallower than PTD (p=0.008). The six early translocations were excluded for this analysis because translocation is unlikely to be driven by scala tympani height so early in the cochlear duct.

Audiologic Outcomes

Postoperative audiologic outcomes were available for 126 ears after exclusion of pediatric patients and pre-lingually deafened patients. Among all patients, CNC word score was directly correlated with AID (r=0.20, p=0.027). When translocated electrodes were analyzed independently, correlation between CNC and AID could not be demonstrated (r=0.11, p=0.553) though this subgroup may have been limited by sample size (N=29).

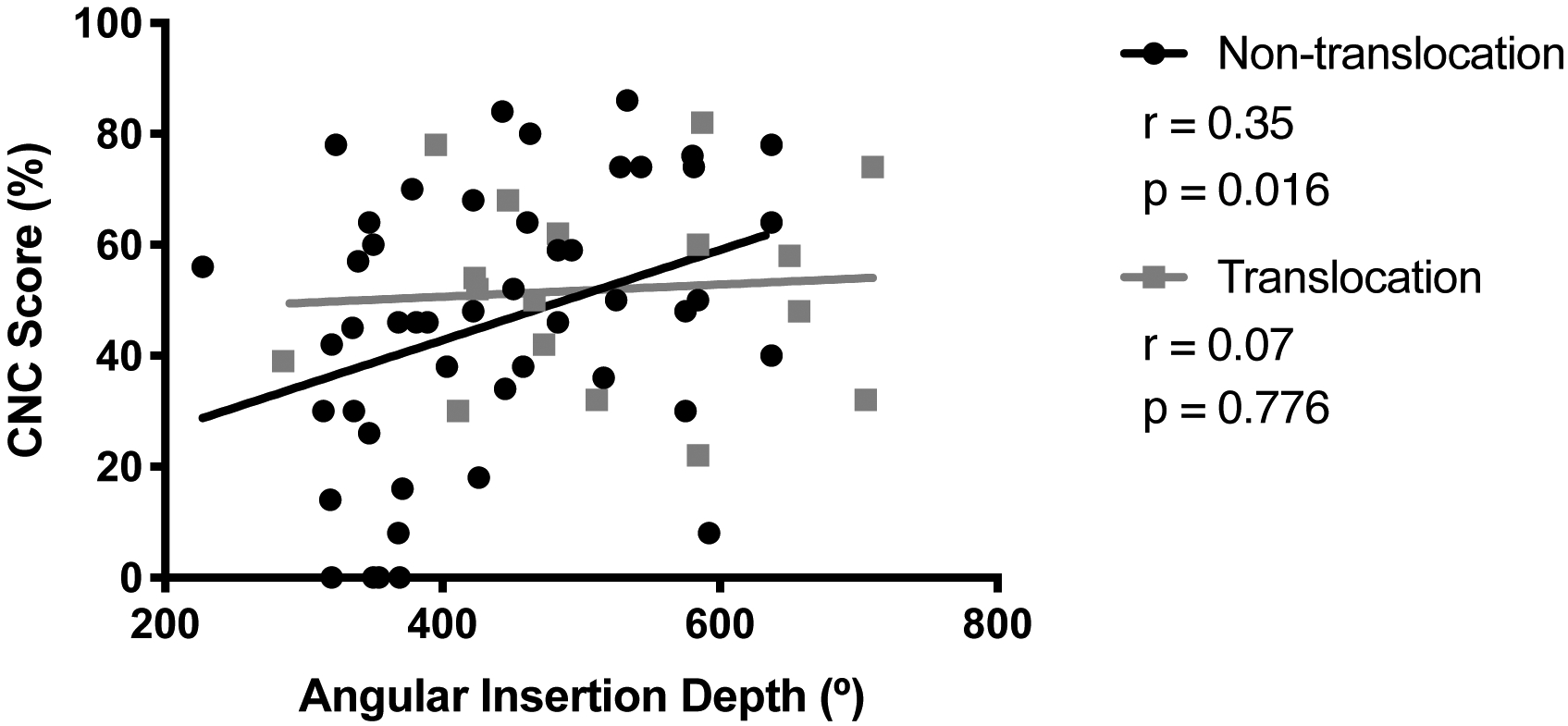

In order to isolate the effects of electric stimulation, patients with residual postoperative hearing (defined as air conduction threshold of ≤80 dB HL at 250 Hz) were excluded. This left 65 ears with no residual postoperative hearing: 48 with non-translocated electrodes and 17 with translocated electrodes. Within this electric-only condition, correlation between CNC and AID was demonstrated in the non-translocated group (r=0.35, p=0.016) but not in the translocated group (r=0.07, p=0.776) as illustrated in Figure 7. The slopes for the two groups were not significantly different from each other (95% confidence interval for slope, non-translocation: 0.016–0.147; translocation: −0.070–0.092).

Figure 7.

For patients without postoperative residual hearing, consonant-nucleus-consonant (CNC) score and angular insertion depth were positively correlated for non-translocated electrodes. There was no correlation for translocated electrodes, but these slopes were not significantly different.

Of note, there were no significant differences in word or sentence scores between patients who did and did not have translocations. Among all patients included in the hearing outcomes analysis, mean CNC was 45% for non-translocated electrodes and 50% for translocated electrodes (p=0.335). Mean AzBio was 59% for non-translocated electrodes and 69% for translocated electrodes (p=0.111).

There were 69 subjects with residual preoperative hearing who also had postoperative air conduction thresholds available. Rates of hearing preservation were 42% (22 of 52) for the non-translocations and 24% (4 of 17) for the translocations, however this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.250). Average AID was similar in cases with vs. without preserved postoperative hearing (446° vs. 462°, p=0.513).

The preoperative to postoperative shift in air conduction threshold at 250 Hz was assessed among patients with preoperative residual hearing and postoperative air conduction thresholds (N=69). The average shift was +28 dB in non-translocations and +39 dB in translocations (p=0.050).

Discussion

In this retrospective review of 177 straight electrodes, we found a 22% translocation rate. Translocation rate did not differ significantly by model. There was a bimodal distribution of translocation depths (Figure 3). The majority of electrodes translocated deeply with a median translocation depth of 381°, and we believe these translocations are driven by anatomic factors including LW ST height. A small subset of six translocations occurred closer to 150–200°. Various factors could drive these early translocations including surgical access (one had facial recess ossification and a high-riding jugular bulb), electrode type (five were CI422/522), or cochlear ossification (though none were noted to have this).

Our measures of ST dimensions show that decreasing ST height along the LW eventually displaces a CI electrode from resting against the LW. This occurred around 400–600° of angular depth. The displaced electrode may either move closer to the modiolus or towards the basilar membrane, risking translocation. LW ST height likely limits insertion and raises translocation risk substantially beyond a certain angular depth. This depth will vary among patients, but translocation risk certainly rises as AID increases (Figure 4). In our cohort, insertion past BMD ≥0.1mm raised translocation risk by a factor of 2.8. Median depth in our cohort where BMD ≥0.1mm was 585°, but care should be taken in applying this broadly as a cutoff for safe insertion depth given that many translocations occurred before this point and we only measured the ST in 45° increments. The use of preoperative CT analysis to specify optimal insertion depth for a given cochlea may represent a unique opportunity to improve insertion technique.

This investigation found that scalar translocation had no effect on CNC or AzBio scores. One explanation may be that straight electrode arrays sit far enough from the modiolar wall that their ability to stimulate spiral ganglion cells is not affected by translocation in a clinically significant way. If this is true, translocation would be expected to have a more significant impact on precurved electrodes, which sit closer to the modiolus. And, indeed, this has been demonstrated in recent studies31. Our group recently completed an analysis of both precurved and straight CI electrodes using a generalized linear model32. Scalar position of the electrode was significantly associated with both CNC and BKB-SIN scores for precurved electrodes but was not associated with either for straight electrodes.

Lack of correlation between translocation status and CNC score may seem to conflict with the finding that CNC and AID are correlated for non-translocated electrodes but not for translocated electrodes (both overall and in the electric-only condition, as shown in Figure 7). However, the 95% confidence intervals overlap for the linear regressions used to compare the non-translocated and translocated groups, so it has not been demonstrated that those slopes are different from one another. The significant p-value for the non-translocated group simply indicates that a correlation between CNC and AID is demonstrated for that group (i.e. slope is significantly non-zero), while the non-significant p-value for the translocated group may reflect an underpowered sample size.

The conclusion that scalar translocation has no effect on CNC score conflicts with the notion that scalar translocation of CI electrodes from ST to SV is associated with worse hearing outcomes. Several studies are frequently cited in support of this hypothesis but fail to address the question directly because either (1) translocations were compared to SV-only insertions8,33 or (2) ST-only insertions were compared to SV-only insertions34 or (3) the majority (59–87%) of electrodes were precurved rather than straight7,16,17. Therefore, existing evidence indicates that (1) SV-only insertions have inferior hearing outcomes compared to ST-SV translocations and ST-only insertions and (2) translocation is associated with worse hearing outcomes when straight and precurved electrodes are considered together. However, no prior studies have addressed hearing outcomes in ST-only insertions vs. ST-SV translocations specifically for straight electrode arrays. Our results suggest that translocation for straight electrodes arrays causes larger drops in low frequency air conduction thresholds but does not impact CNC or AzBio scores and does not affect hearing preservation rates as measured by CNC score.

Regardless of translocation’s impact on CNC scores, we continue to believe that structural preservation within the cochlea will help avoid long-term scarring and neuronal death. Our results indicate that ST anatomy inherently places limits on insertion depth for every patient. Preoperative planning to customize insertion depths may help decrease insertion trauma, and post-insertion imaging will be necessary to allow identification of final electrode array location providing feedback for refinement of surgical technique35.

Conclusion

CNC is directly correlated with AID for straight CI electrode arrays, at least when they are placed fully within the ST. Translocations generally occur around 380° and are more common with deeper insertions due to decreasing LW ST height leading to BM displacement. Risk of translocation increases significantly after 580° of AID. Translocation causes greater shifts in low frequency air conduction thresholds but does not lead to worse CNC or AzBio scores.

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported by the 2018 AAO-HNSF Resident Research Award sponsored by Xoran Technologies, LLC. This work was also supported by grants R01008408 and R01014462 from the National Institute on Deafness and other Communication Disorders as well as grant R0113117 from the National Institute of Health. This content is the sole responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of this institute.

Footnotes

Disclosures:

R.F.L. is a consultant for Advanced Bionics, Ototronix, and Medtronic. J.T.H. is a consultant for Advanced Bionics. No other conflicts of interest.

Presentations:

Presented Sept 2019 at American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery Annual Meeting 2019 in New Orleans, LA.

References

- 1.Wang J, Dawant BM, Labadie RF, Noble JH. Retrospective Evaluation of a Technique for Patient-Customized Placement of Precurved Cochlear Implant Electrode Arrays. Otolaryngol - Head Neck Surg (United States). 2017;157:107–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hardy M The length of the organ of Corti in man. Am J Anat. 1938;62:291–311. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Úlehlová L, Voldřich L, Janisch R. Correlative study of sensory cell density and cochlear length in humans. Hear Res. 1987;28:149–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Erixon E, Högstorp H, Wadin K, Rask-Andersen H. Variational anatomy of the human cochlea: Implications for cochlear implantation. Otol Neurotol. 2009;30:14–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gantz BJ, Dunn C, Oleson J, Hansen M, Parkinson A, Turner C. Multicenter clinical trial of the Nucleus Hybrid S8 cochlear implant: Final outcomes. Laryngoscope. 2016;126:962–973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suhling MC, Majdani O, Salcher R, et al. The Impact of Electrode Array Length on Hearing Preservation in Cochlear Implantation. Otol Neurotol. 2016;37:1006–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holden LK, Finley CC, Firszt JB, et al. Factors affecting open-set word recognition in adults with cochlear implants. Ear Hear. 2013;34:342–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finley CC, Holden TA, Holden LK, et al. Role of electrode placement as a contributor to variability in cochlear implant outcomes. Otol Neurotol. 2008;29:920–928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rivas A, Cakir A, Hunter JB, et al. Automatic Cochlear Duct Length Estimation for Selection of Cochlear Implant Electrode Arrays. Otol Neurotol. 2017;38:339–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Connell BP, Hunter JB, Haynes DS, et al. Insertion depth impacts speech perception and hearing preservation for lateral wall electrodes. Laryngoscope. 2017;127:2352–2357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Helbig S, Adel Y, Leinung M, Stöver T, Baumann U, Weissgerber T. Hearing Preservation Outcomes after Cochlear Implantation Depending on the Angle of Insertion: Indication for Electric or Electric-Acoustic Stimulation. Otol Neurotol. 2018;39:834–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Noble JH, Labadie RF, Majdani O, Dawant BM. Automatic segmentation of intracochlear anatomy in conventional CT. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2011;58:2625–2632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao Y, Dawant BM, Labadie RF, Noble JH. Automatic localization of cochlear implant electrodes in CT. Int Conf Med Image Comput Comput Interv. 2014;17:331–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noble JH, Dawant BM. Automatic graph-based localization of cochlear implant electrodes in CT. Lect Notes Comput Sci (including Subser Lect Notes Artif Intell Lect Notes Bioinformatics). 2015;9350:152–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boyer E, Karkas A, Attye A, Lefournier V, Escude B, Schmerber S. Scalar localization by cone-beamcomputed tomography of cochlear implant carriers: A comparative study between straight and periomodiolar precurved electrode arrays. Otol Neurotol. 2015;36:422–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Connell BP, Cakir A, Hunter JB, et al. Electrode Location and Angular Insertion Depth Are Predictors of Audiologic Outcomes in Cochlear Implantation. Otol Neurotol. 2016;37:1016–1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wanna GB, Noble JH, Carlson ML, et al. Impact of electrode design and surgical approach on scalar location and cochlear implant outcomes. Laryngoscope. 2014;124:S1–S7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wanna GB, Noble JH, Gifford RH, et al. Impact of Intrascalar Electrode Location, Electrode Type, and Angular Insertion Depth on Residual Hearing in Cochlear Implant Patients: Preliminary Results. Otol Neurotol. 2015;36:1343–1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hatsushika SI, Shepherd RK, Tong YC, Clark GM, Funasaka S. Dimensions of the scala tympani in the human and cat with reference to cochlear implants. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1990;99:871–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wysocki J Dimensions of the human vestibular and tympanic scalae. Hear Res. 1999;135:39–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ketterer MC, Aschendorff A, Arndt S, et al. The influence of cochlear morphology on the final electrode array position. Eur Arch Oto-Rhino-Laryngology. 2018;275:385–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Avci E, Nauwelaers T, Lenarz T, Hamacher V, Kral A. Variations in microanatomy of the human cochlea. J Comp Neurol. 2014;522:3245–3261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Noble JH, Gifford RH, Labadie RF, Dawant BM. Statistical Shape Model Segmentation and Frequency Mapping of Cochlear Implant Stimulation Targets in CT. Med Image Comput Comput Assist Interv. 2012;15:421–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schuman TA, Noble JH, Wright CG, Wanna GB, Dawant B, Labadie RF. Anatomic verification of a novel method for precise intrascalar localization of cochlear implant electrodes in adult temporal bones using clinically available computed tomography. Laryngoscope. 2010;120:2277–2283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peterson GE, Lehiste I. Revised CNC Lists for Auditory Tests. J Speech Hear Disord. 1962;27:62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spahr AJ, Dorman MF, Litvak LM, et al. Development and validation of the azbio sentence lists. Ear Hear. 2012;33:112–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gatehouse S, Noble I. The Speech, Spatial and Qualities of Hearing Scale (SSQ). Int J Audiol. 2004;43:85–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sheffield SW, Gifford RH. The benefits of bimodal hearing: Effect of frequency region and acoustic bandwidth. Audiol Neurotol. 2014;19:151–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dorman MF, Gifford RH. Combining acoustic and electric stimulation in the service of speech recognition. Int J Audiol. 2010;49:912–919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adult F, Implant C. Minimum Speech Test Battery ( MSTB ). Minimum Speech Test Battery For Adult Cochlear Implant Users.

- 31.Shaul C, Dragovic AS, Stringer AK, O’Leary SJ, Briggs RJ. Scalar localisation of peri-modiolar electrodes and speech perception outcomes. J Laryngol Otol. 2018;132:1000–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chakravorti S, Noble JH, Gifford RH, et al. Further Evidence of the Relationship Between Cochlear Implant Electrode Positioning and Hearing Outcomes. Otol Neurotol. 2019;40:617–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Skinner MW, Holden TA, Whiting BR, et al. In Vivo Estimates of the Position of Advanced Bionics Electrode Arrays in the Human Cochlea. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2007;116:2–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aschendorff A, Kromeier J, Klenzner T, Laszig R. Quality control after insertion of the nucleus contour and contour advance electrode in adults. Ear Hear. 2007;28:75S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Labadie RF, Schefano AD, Holder JT, et al. Use of intraoperative CT scanning for quality control assessment of cochlear implant electrode array placement. Acta Otolaryngol. 2019. December 20:1–6. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]