Abstract

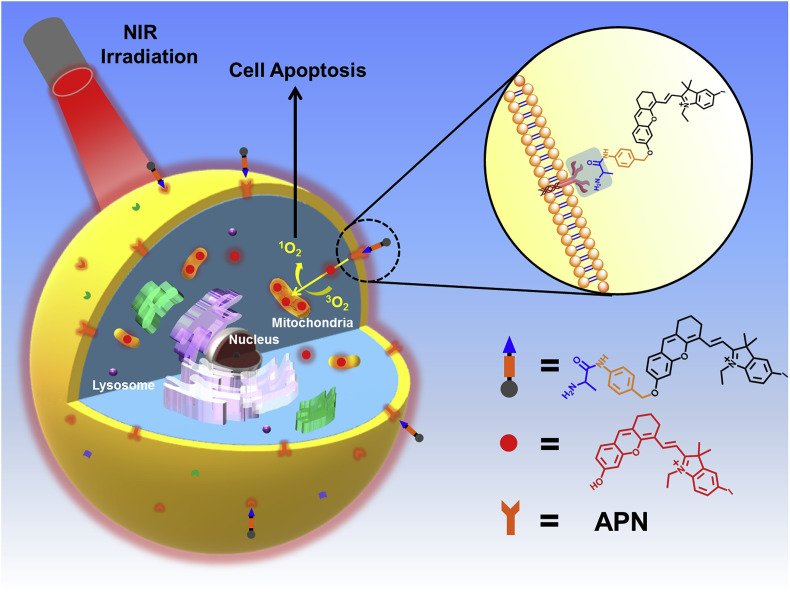

Photodynamic therapy has been developed as a prospective cancer treatment in recent years. Nevertheless, conventional photosensitizers suffer from lacking recognition and specificity to tumors, which causing severe side effects to normal tissues, while the enzyme-activated photosensitizers are capable of solving these conundrums due to high selectivity towards tumors. APN (Aminopeptidase N, APN/CD13), a tumor marker, has become a crucial targeting substance owing to its highly expressed on the cell membrane surface in various tumors, which has become a key point in the research of anti-tumor drug and fluorescence probe. Based on it, herein an APN-activated near-infrared (NIR) photosensitizer (APN-CyI) for tumor imaging and photodynamic therapy has been firstly developed and successfully applied in vitro and in vivo. Studies showed that APN-CyI could be activated by APN in tumor cells, hydrolyzed to fluorescent CyI-OH, which specifically located in mitochondria in cancer cells and exhibited a high singlet oxygen yield under NIR irradiation, and efficiently induced cancer cell apoptosis. Dramatically, the in vivo assays on Balb/c mice showed that APN-CyI could achieve NIR fluorescence imaging (λem = 717 nm) for endogenous APN in tumors and possessed an efficient tumor suppression effect under NIR irradiation.

Keywords: Aminopeptidase N, Enzyme-activated photosensitizer, PDT, NIR fluorescence imaging

1. Introduction

In recent years, photodynamic therapy (PDT) has been extensively developed as a prospective cancer therapeutics [[1], [2], [3], [4], [5]]. The process of photodynamic therapy involves delivering photosensitizer (PS) to the tumor site and irradiating with particular wavelength in tumor region, which can activate the photosensitizer to convert oxygen molecules (3O2) into singlet oxygen (1O2) or ROS with extremely high reactive activity [6,7]. These reactive oxygen species can damage cell structure through oxidative stress and induce cell death [8]. Compared with traditional chemotherapy, radiotherapy and surgery, photodynamic therapy possesses the advantages of minimally invasive, negligible drug resistance and controllable treatment region selection [9,10], especially photosensitizers with near infrared (NIR) absorption and emission own the advantages of deep tissue penetration and excellent anti-interference capability, which are proper for application in vivo [[11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16]]. To date, plentiful NIR photosensitizers based on different fluorophores have been developed [[17], [18], [19], [20]]. However, most photosensitizers suffered from lacking tumor specificity, and the normal cells could also be damaged when exposed to irradiation ascribed to the “on” state of conventional photosensitizers, which could lead to many serious consequences [21]. To overcome this problem, activatable photosensitizers have been proposed and applied in tumor imaging and therapy due to high selectivity to cancer cells and relatively low toxicity to normal cells [22,23]. Meanwhile, because of the activation, it is possible to distinguish cancer cells from normal cells. Up to now, a number of activatable photosensitizers have been developed on the basis of some overexpressed species in tumor microenvironment (TME) [[24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31]]. Therein, enzyme-activated photosensitizers are most promising because of superb selectivity and admirable biological responsiveness [[32], [33], [34]], which will be a key point in PSs’ studies and clinical value of cancer therapy in future.

Aminopeptidase N (APN/CD13), known as membrane binding zinc-ion-dependent type II metalloproteinase, can degrade neutral or basic amino acids from the N-terminal of the protein polypeptide chain [35,36]. APN participates in a number of important physiological and pathological processes in the body accordingly, such as signal transduction, immune regulation, hydrolysis of bioactive peptides and taking part in the coronavirus invasion process [37]. What's more, numerous studies have shown that APN is highly expressed on the surface of most tumor cells compared with normal cells because APN plays a crucial role in the growth, invasion, metastasis and angiogenesis of malignant tumors [[38], [39], [40], [41]]. Thus, APN owns the potential to be a biomarker to recognize tumor cells and then has become a noteworthy target in the research of fluorescence probes and anti-tumor drugs [42]. However, most well-performing APN-activated fluorescence molecules only placed emphasis on the ability of tumor imaging, which limited their further applications [[43], [44], [45], [46]]. Whereas photosensitizers activated by APN achieving the integration of tumor imaging and photodynamic therapy are infrequent and meritorious, which become a potent implement in the field of cancer therapeutics.

In this work, a NIR photosensitizer (APN-CyI) which could be activated by APN not only for tumor imaging but also for photodynamic therapy was firstly developed. As depicted in Scheme 1 , after being recognized, APN-CyI would be hydrolyzed, thereby forming CyI-OH, which was a hemicyanine fluorophore with NIR feature, good light stability, solubility and low biological toxicity [47], especially, with photodynamic effect due to the heavy atom effect of halogen elements. By introducing iodine into the indole ring, the intersystem crossing (ISC) process was improved and the singlet oxygen yield was also increased as well [48]. As a strong electron donor, the hydroxyl group in CyI-OH greatly enhanced the NIR fluorescence signal at 717 nm based on intramolecular charge transfer (ICT) effect compared with APN-CyI. After activation, CyI-OH was specifically located on mitochondria ascribed to the positive charge in hemicyanine fluorophore. Furthermore, the activated molecule CyI-OH possessed higher 1O2 yield than APN-CyI, resulting in significantly killing effect on cancer cells (HepG-2&4T1) compared to normal cells (LO2). APN-CyI imaging and PDT experiments on tumor transplanted Balb/c mice demonstrated that it could be activated by endogenous tumor APN in vivo, and it had obvious inhibition on tumor, which declared APN-CyI might be a worthwhile tool in tumor therapeutics. Hence, the functions of tumor imaging and PDT were effectively integrated.

Scheme 1.

The preparation scheme of APN-CyI for APN imaging and cancer therapy.

2. Experimental section

2.1. General information and materials

Unless otherwise specified, all reagents were purchased from commercial suppliers. The ultrapure water used in all experiments came from Milli-Q system. 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on Bruker Avance II 400 MHz or 500 MHz spectrometer (TMS as the internal standard). Mass spectra were performed on the Agilent Technologies HP1100LC/MSD MS and a Thermo Fisher LC/Q-TOF-MS instruments. Absorption spectra were achieved on the Agilent Technologies CARY 60 UV–Vis spectrophotometer and fluorescence spectra were measured on a VAEIAN CARY Eclipse fluorescence spectrophotometer. All the Spectrum experiments were carried out in a quartz cell (10 × 10 mm). All the cell imaging experiments were performed under the Olympus FV 1000 and FV1000-IX81 confocal microscopy (Olympus, Japan). Cytotoxicity assays were analyzed by Thermo Varioskan™ LUX multifunctional microplate reader. All the BALB/c mice were purchased from SPF laboratory center of Dalian Medical University. And the mice imaging experiments were carried out on NightOWL II LB983 small animal in vivo imaging system (German).

2.2. Synthesis of photosensitizer APN-CyI

The synthetic route of APN-CyI is shown in Scheme S1.

2.2.1. Synthesis of compound 1

4-Aminobenzyl alcohol (400 mg, 3.25 mM), (tert-butoxycarbonyl)-l-alanine (567 mg, 3 mM), HATU (1.14 g, 3 mM) and DIPEA (776 mg, 3 mM) were dissolved in 15 mL anhydrous tetrahydrofuran. The mixture was stirred at 0 °C under nitrogen protection for 10 min, then at room temperature for overnight. After the solvent was removed under vacuum, the dark crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography with PE/EA = 2/1 to obtain compound 1 as a yellow white solid (Yield: 82%). ESI-HRMS: m/z calcd for [M+Na]+: 317.1477, found: 317.1478.1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.92 (s, 1H), 7.43 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.18 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 5.43 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 1H), 2.85 (s, 1H), 1.47 (s, 9H), 1.45 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 3H).

2.2.2. Synthesis of compound 2

Compound 1 (200 mg, 0.67 mM), 4-toluene sulfonyl chloride (152.5 mg, 0.8 mM) were dissolved in 15 mL anhydrous dichloromethane, triethylamine (0.5 mL) was added dropwise. Then the mixture was stirred at 0 °C under nitrogen protection for 3 h. The solvent was removed at vacuum and the crude product was further purified through silica gel column chromatography with DCM to obtain compound 2 as a white solid (Yield: 22%). Compound 3 was unstable and directly used in next step.

2.2.3. Synthesis of compound 3

Compound 3 was synthesized according to previous literature [33]. ESI-HRMS: m/z calcd for [M-I-]+: 314.0400, found 314.0407.

2.2.4. Synthesis of compound 4

Anhydrous N, N-Dimethylformamide (5.6 mL, 72.5 mM), trichloromethane (25 mL) were stirred at 0 °C. Then PBr3 (6.2 mL, 65.3 mM) was added dropwise through a constant pressure drip funnel. Then the reaction was stirred for 1 h. A mass of yellowish solids were formed in reaction. Cyclohexanone (2.5 mL, 24.2 mM) was added to the mixture. The reaction was stirred at 25 °C for overnight. Pour the red solution on 100 g ice and add NaHCO3 until the solution is neutral. After separation, the aqueous layer was extracted with DCM (25 mL), the organic layer was dried with MgSO4. Then the solvent was removed at vacuum to obtain compound 4 as a red oily liquid (3.42 g) and no further purification is required.

2.2.5. Synthesis of compound 5

Compound 4 (2.27 g, 12 mM), 2-hydroxy-4-methoxybenzaldehyde (1.52 g, 10 mM) and Caesium carbonate (8.0 g) were stirred in 15 mL N,N-Dimethylformamide at 25 °C for 16 h. Then the dark mixture was diluted with 50 mL water, extracted with 50 mL DCM. The organic layer was washed with (50 mL × 3) water, dried over Na2SO4. The solvent was dried under reduced pressure and the crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography with PE/EA = 10/1 to obtain yellow crystalline compound 5 (Yield: 37.7%). ESI-HRMS: m/z calcd for [M+H]+: 243.1021, found 243.1018.1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.32 (s, 1H), 7.08 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 6.66 (m, J = 7.3 Hz, 3H), 3.85 (s, 3H), 2.62–2.52 (m, 2H), 2.45 (t, J = 5.9 Hz, 2H), 1.77–1.48 (m, 2H).

2.2.6. Synthesis of CyI-OMe

Compound 5 (363 mg, 1.5 mM), compound 3 (794 mg, 1.8 mM) and potassium carbonate (415 mg, 3.0 mM) were dissolved in 15 mL acetic anhydride. The mixture was stirred at 80 °C for 12 h 50 mL water was added to dilute the solvent. Then the dark blue mixture was extracted with 100 mL DCM. The organic layer was washed by 50 mL saturated NaCl solution for three and dried over Na2SO4. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography with DCM/MeOH = 30/1 to obtain CyI-OMe as a blue solid with metallic sheen (Yield: 91.1%). ESI-HRMS: m/z calcd for [M-I-]+: 538.1237, found 538.1235.1H NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD) δ 8.77 (d, J = 14.7 Hz, 1H), 8.01 (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.86 (dd, J = 8.4, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.57–7.46 (m, 2H), 7.32 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.07 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.02 (dd, J = 8.6, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 6.46 (d, J = 14.7 Hz, 1H), 4.34 (q, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 3.97 (d, J = 5.3 Hz, 3H), 2.87–2.78 (m, 2H), 2.74 (t, J = 6.1 Hz, 2H), 2.02–1.88 (m, 2H), 1.82 (s, 5H), 1.46 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 3H).

2.2.7. Synthesis of CyI-OH

CyI-OMe (100 mg, 0.15 mM) was dissolved in 15 mL anhydrous dichloromethane and stirred at 0 °C. Then 0.5 mL BBr3 was dissolved in 1 mL anhydrous dichloromethane and added dropwise to the mixture in 10 min by an injection syringe. After addition, the solution gradually changed from blue to yellow and the mixture was react at 25 °C for 12 h. After the reaction was finished, 20 mL water was added into the mixture gradually at an ice bath. NaHCO3 was added until the solution is neutral. The mixture was extracted with 100 mL DCM and the organic layer was washed by 50 mL water. The solvent was dried over Na2SO4 and removed by vacuum. The crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography with DCM/MeOH = 15/1 to obtain CyI-OH as a blue solid with metallic sheen (Yield: 83%). ESI-HRMS: m/z calcd for [M]+: 524.1081, found: 524.1087.1H NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD) δ 8.58 (d, J = 14.1 Hz, 1H), 7.90 (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.83–7.66 (m, 1H), 7.61 (s, 1H), 7.45 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 7.14 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 6.83 (dd, J = 8.7, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 6.74 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H), 6.22 (d, J = 14.3 Hz, 1H), 4.18 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 2.85–2.76 (m, 2H), 2.72 (t, J = 6.1 Hz, 2H), 2.04–1.87 (m, 2H), 1.76 (s, 6H), 1.40 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 4H).

2.2.8. Synthesis of Boc-APN-CyI

Compound 2 (60 mg, 0.13 mM), CyI-OH (87 mg 0.13 mM), potassium carbonate (90 mg, 0.65 mM) and sodium iodide (15 mg, 0.1 mM) were dissolved in 20 mL acetonitrile. The mixture was stirred at 80 °C for 5 h. The solvent was removed by vacuum, and the crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography with DCM/MeOH = 20/1 to obtain Boc-APN-CyI as a blue solid (Yield: 77%). Boc-APN-CyI was no need to characterize the structure and directly used in next step.

2.2.9. Synthesis of APN-CyI

Boc-APN-CyI (60 mg, 0.065 mM) was dissolved in 10 mL anhydrous dichloromethane. Then 1 mL trifluoroacetic acid was dissolved in 1 mL dry DCM and added dropwise to the mixture above at 0 °C. After added, the mixture was stirred at room temperature for another 1 h. The solvent was removed under reduce pressure and the crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography with DCM/MeOH = 10/1 to obtain APN-CyI as a blue solid with metallic sheen (Yield: 68%). ESI-HRMS: m/z calcd for [M-I-]: 700.2031, found 700.2041.1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 8.79 (d, J = 14.7 Hz, 1H), 8.04 (s, 1H), 7.89 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 7.70 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.53 (t, J = 8.6 Hz, 4H), 7.36 (s, 1H), 7.16 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.10 (dd, J = 8.7, 2.3 Hz, 1H), 6.48 (d, J = 14.7 Hz, 1H), 5.27 (s, 2H), 4.35 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 4.10 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 2.88–2.78 (m, 2H), 2.75 (t, J = 5.9 Hz, 2H), 2.03–1.90 (m, 3H), 1.84 (s, 6H), 1.62 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 4H), 1.47 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 4H), 1.31 (s, 2H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CD3OD) δ 177.69, 169.36, 164.01, 156.04, 147.30, 145.70, 142.55, 139.34, 136.31, 133.97, 133.15, 130.32, 129.72, 128.81, 121.27, 117.58, 116.39, 115.70, 115.29, 103.92, 102.73, 91.84, 71.53, 51.79, 50.96, 41.36, 30.06, 28.26, 25.09, 21.67, 17.66, 12.71.

2.3. Determination of the detection limit

The imaging detection limit (DL) of APN-CyI was determined by fluorescence titration under different concentrations of APN (0–50 ng/mL). The fluorescence intensity of APN-CyI blank samples was measured several times to obtain the standard deviation. The detection limit is calculated by the following equation:

| Detection limit = 3σ/k |

Where σ is the standard deviation of blank samples, and k is the slope of fluorescence intensity (F717 nm) to APN concentrations.

2.4. Singlet oxygen detection in vitro

The singlet oxygen was detected according to the following method, DPBF (1, 3-diphenlisobenzofuran) was used as singlet oxygen capture agent. In methanol, the DPBF absorbance at 415 nm was adjusted to about 1.0, subsequently, APN-CyI and CyI-OH with the same concentration (5 μM) was added to quartz cells respectively. Then the quartz cells were exposed at 690 nm irradiation (3.0 mW). And the absorbtion spectra of the mixture were detected every 5 min.

2.5. Cell incubation

Hepatoma carcinoma cells (HepG-2 cells), normal liver cells (LO2 cells) and breast cancer cells (4T1 cells) were purchased from Institute of Basic Medical Sciences (IBMS) of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences. And all cells were incubated with Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM, Invitrogen) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen). The cells were treated at 37 °C under a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

2.6. Cytotoxicity assays

Cell viability was determined by the reduction of MTT (3-(4, 5)-dimethylthiahiazo (-2-yl)-3, 5-diphenytetrazoliumromide) to formazan by succinic acid dehydrogenase in the mitochondria of living cells (MTT assay). HepG-2 and LO2 cells were incubated in 96-well microplates (Nunc, Denmark). Every wells were seeded a density of 1 × 105 cells/ml cells in 100 μL DMEM medium containing 10% FBS. After 24 h incubation, the dark groups were cultured in 100 μL DMEM medium with different concentrations of APN-CyI (4, 3, 2.5, 2, 1.5, 1, 0.5, 0.25, 0 μM) for 12 h. And the irradiation groups were cultured in 100 μL DMEM medium with different concentrations of APN-CyI (4, 3, 2.5, 2, 1.5, 1, 0.5, 0.25, 0 μM) for 100 min, subsequently, the 96-well microplates with cells were exposed under 660 nm irradiation (20 mW/cm2) for 20 min, then the cells were incubated for another 12 h. After 12 h incubation, the medium was removed and 100 μL medium with MTT (0.5 mg/mL) was added to each well and the plates were incubated at 37 °C for another 4 h (MTT mother liquor of 5 mg/mL was diluted 10 times with medium). Then the medium was removed, the formazan was dissolved in 100 μL DMSO for each well. And the fluorescence intensity of the solutions in each well was measured by a multifunctional microplate reader at 570 nm and 630 nm. The cell viability was calculated by the following formula:

| Cells viability (%) = (OD570 – OD630) dye / (OD570 – OD630) control × 100 |

2.7. Imaging endogenous APN activity of living cells

HepG-2, LO2 cells were plated to cell culture dishes with a density of 1 × 104 cells/mL and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C under a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Then the control groups were treated with PBS, another groups were treated with 2 μM APN-CyI at 37 °C for 120 min. Furthermore, 50 μM bestatin (a competitive APN inhibitor) was added to the dishes for a 60 min incubation to study the effect of APN activity on fluorescence detection, subsequently, the inhibition groups were treated with 2 μM APN-CyI at 37 °C for 120 min. After incubation, the dishes were washed by DMEM without FBS for three times to remove the dye in solution. And the cells were imaged by a FV1000-IX81 confocal microscopy with a 60× objective lens (λex = 640 nm, λem = 700–800 nm).

2.8. Imaging singlet oxygen in living cells

HepG-2 cells were seeded to cell culture dishes with a density of about 1 × 104 cells/ml and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C under a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Then all the cells were treated with 3 μM APN-CyI at 37 °C for 120 min. DCFH-DA (10 μM) as a singlet oxygen capture agent was added to the medium for 20 min incubation, in addition, NAC (N-acetyl-l-cysteine, 50 e. q) was added to one group to quench singlet oxygen. Then the irradiation group and the NAC group were exposed under 660 nm (100 mW/cm2) irradiation for 5 min and imaged by the confocal microscopy with a 60× objective lens immediately. The dark group received no treatment prior to imaging (λex = 488 nm, λem = 500–550 nm).

2.9. Cell viability imaging experiment

Calcein-AM and Propidium Iodide (PI) were employed to detect the cell viability with fluorescence imaging. HepG-2 cells were seeded to cell culture dishes with a density of about 1 × 104 cells/mL and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C under a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Then all the cells were treated with 3 μM APN-CyI at 37 °C for 120 min. Subsequently, the cells were exposed to 660 nm irradiation (20 mW/cm2) for 0, 10, 20 min and were incubated for another 12 h. The DMEM medium was replaced by 2 mL PBS and Calcein-AM and PI (1 μL) were carefully added by a pipetting gun. After a 20 min incubation, the three groups were imaged by the confocal microscopy with a 10× objective lens (Calcein-AM: λex = 488 nm, λem = 500–550 nm; PI: λex = 561 nm, λem = 590–640 nm).

2.10. Cell apoptosis imaging

Annexin V-FITC and Propidium Iodide (PI) were used to measure cell apoptosis with fluorescence imaging. HepG-2 cells were seeded to cell culture dishes with a density of about 1 × 104 cells/mL and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C under a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Then all the cells were treated with 1 μM APN-CyI at 37 °C for 120 min. Subsequently, the cells were exposed to 660 nm irradiation (20 mW/cm2) for 20 min and were incubated for 20 min or 3 h. The DMEM medium was replaced by 2 mL binding buffer and Annexin V-FITC and PI (5 μL) were carefully added by a pipetting gun. After a 10 min incubation, the cells were imaged by the confocal microscopy with a 10× objective lens (Annexin V-FITC: λex = 488 nm, λem = 500–550 nm; PI: λex = 561 nm, λem = 590–640 nm).

2.11. Fluorescence imaging on 4T1-tumor mice model

All the experiments and operations were carried out with guide for the care and use of laboratory animal resources and Dalian Medical University animal care and use committee and approved by the institutional animal care and use committee of the Dalian Medical University. Mice breast cancer cells (4T1 cells) were employed to establish the tumor mice models. When female Balb/c mice weighed about 20 g, the 4T1 cells were inoculated to their armpits. After two weeks of growth, when the volume of 4T1 tumors reached 100 mm3, the mice were subjected to the intratumoral injection of 100 μL APN-CyI (100 μM) within the period of anesthesia. And the fluorescence imaging of 4T1-tumor mice was carried out on a NightOWL II LB983 small animal in vivo imaging system (German).

2.12. Tumor suppression experiments of APN-CyI on 4T1-tumor mice model

4T1 cells were inoculated to female Balb/c mice weighed about 20 g When the volume of 4T1 tumors reached 100 mm3, they were divided into 4 groups, the dark group was treated with 200 μL saline, the light groups was treated with 200 μL saline and exposed under 660 nm irradiation for 20 min, the A-dark group was treated with 200 μL APN-CyI (100 μM) and the A-light group was treated with 200 μL APN-CyI (100 μM) and exposed under 660 nm irradiation for 20 min. All the groups were given saline or photosensitizer through intratumoral injection within the period of mice anesthesia and the irradiation was conducted after injection for approximately 100 min. The weight of mice and the volume of tumors were measured every two days until three weeks. The volume of tumors was calculated by the following formula:

| V = 1/2 × a × b2 |

V represents tumor volume, a represents the longest diameter of the tumor site, and b represents the diameter perpendicular to a.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Design and synthesis of photosensitizer APN-CyI

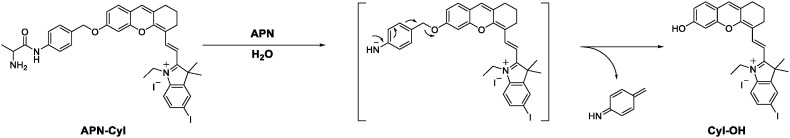

The hemicyanine fluorophore possessed an obvious D-π-A structure, such structure was widely used in NIR fluorescence imaging. And by introducing halogen heavy atom into the indole ring, the singlet oxygen yield of the hemicyanine fluorophore was significantly increased. Hence, by concatenating the hemicyanine fluorophore CyI-OH and the l-alanine modification ligand through a 4-aminobenzyl alcohol linkage, we successfully synthesized an APN enzyme-triggered photosensitizer APN-CyI, which was accurately characterized by high resolution mass spectrometry (ESI-HRMS), nuclear magnetic resonance hydrogen spectroscopy (1H NMR) and carbon spectroscopy (13C NMR). The response mechanism of APN-CyI to APN is shown in Scheme 2 .

Scheme 2.

Response mechanism of APN-CyI with APN.

3.2. Spectral properties and responses to APN

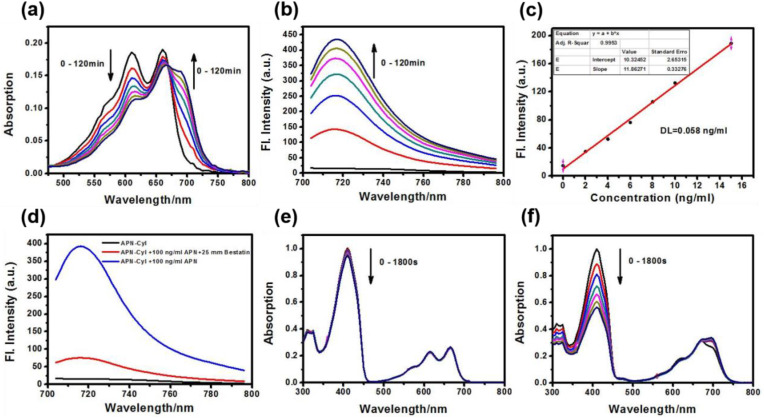

Firstly, we studied the absorption and emission spectra of APN-CyI in different solvents (Fig. S1). Enzymatic hydrolysis of substrates required the aqueous environment, hence we investigated the spectral properties of photosensitizer APN-CyI in aqueous solution (PBS/DMSO = 9/1, v/v, 10 mM, pH = 7.4). In order to confirm that the l-alanine moiety of APN-CyI could be cleaved by APN enzyme, the APN-CyI solution (5 μM) was treated with 100 ng/mL APN at 37 °C. With the reaction processed, an obvious red shift from 610 nm to 685 nm in absorption spectral was observed accompanied by the color change of solution from blue to green in 120 min (Fig. 1 a and Fig. S2a). Meanwhile, the fluorescence intensity at 717 nm was significantly enhanced (Fig. 1b and Fig. S2b), which demonstrated that the l-alanine modification ligand could be hydrolyzed by APN and released CyI-OH. Consequently, the fluorescence quantum yield increased from 0.005 (APN-CyI) to 0.024 (CyI-OH) in aqueous solution (PBS/DMSO = 9/1, v/v, 10 mM, pH = 7.4).

Fig. 1.

(a) UV–vis absorption and (b) fluorescence spectra changes of APN-CyI (5 μM) with APN in 120 min. (c) Linear relationship between the fluorescence intensity of APN-CyI (5 μM) at 717 nm and various concentrations of APN (0–15 ng/mL). (d) Fluorescence spectra of APN-CyI (5 μM) inhibition tests. λex = 685 nm, slit: 10/5 nm. (e) (f) Attenuation curve of DPBF treated with APN-CyI (e) and CyI-OH (f) under 690 nm irradiation in 0–1800 s in MeOH.

Moreover, in order to test the sensitivity of APN-CyI, the concentration titration experiment was conducted (Fig. S2c), and what gratifying was that there was a good linear relationship between the concentration of APN and the fluorescence intensity, despite the extremely low enzyme concentration (0–15 ng/mL) (Fig. 1c). The detection limit for APN is 0.058 ng/mL, which is lower than most reported molecules that respond to APN [[43], [44], [45]]. This fact testified that APN-CyI could be used to detect APN quantitatively in vitro.

Good specificity is a key point for activated photosensitizer to achieve imaging in vivo. To evaluate the selectivity of APN-CyI to common biochemical molecules, metal salts (NaCl; KBr; CaCl2; NiCl2; MgCl2; NH4Cl; NaI; NaClO4; NaOAc; Na2CO3; Na2S; NaNO3; NaNO2), reactive oxygen species (NaClO; H2O2), reductive species (GSH; AA) and tumor-related enzymes (NTR; GGT) were treated with our photosensitizer in aqueous solution for 120 min at 37 °C (Fig. S2c). Only APN could induce an extremely strong fluorescence enhancement of APN-CyI, which verified APN-CyI was highly selective to APN under physiological condition.

In order to study the response mechanism of APN-CyI reacted with APN, the solution before and after the response was analyzed by high resolution mass spectrometry. A distinct peak at m/z = 700.2034 (calcd. 700.2031 for [M-I-]+) was found in the solution before response attributed to APN-CyI (Fig. S3a). While a peak at m/z = 524.1085 (calcd. 524.1081 for [M-I-]+) was observed after a treatment with APN (Fig. S3b), which strongly implied that the alanine modified group was hydrolyzed to generate CyI-OH. Moreover, an APN activity inhibition experiment was also performed to indirectly illustrate the response mechanism. When APN was pretreated with 25 μM bestatin (a competitive inhibitor of APN), the fluorescence intensity significantly decreased after the response, which indicated that the catalytic activity of APN was significantly inhibited (Fig. 1d). Hence, these facts proved that APN activated APN-CyI by hydrolyzing the alanine amide bond to form CyI-OH.

Good photostability is a prerequisite for effective use of photosensitizer. Therefore, the solution of APN-CyI (10 μM) was exposed at 660 nm irradiation (20 mW/cm2) for 10 min. As depicted in Fig. S4a, the absorption intensity of APN-CyI decreased only slightly in 10 min, which proved that APN-CyI had a good photostability and was suitable for photodynamic therapy.

To verify whether the photosensitizer was activated in response to APN, the singlet oxygen (1O2) was detected by employing DPBF (1, 3-diphenlisobenzofuran) as a capture agent. Compared to APN-CyI, a dramatic drop at 415 nm was observed when the DPBF solution mixed with CyI-OH was exposed at an irradiation (690 nm, 3.0 mW) for 1800 s, which mightily demonstrated that the hydrolytic product CyI-OH possessed a considerable singlet oxygen yield compared with APN-CyI (Fig. 1e and f). To further shed light on this phenomenon, Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) was provided to perceive 1O2 by utilizing TEMP (2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine) as a trapping agent. Compared with APN-CyI, an evident characteristic 1O2 signal (TEMPO) was observed in CyI-OH aqueous solution, verified the enhancement of singlet oxygen yield after activation (Fig S4b). As to the cause of this phenomenon, we deem that the Intramolecular Charge Transfer (ICT) process may be restrained and the energy of the excited state be mainly released through the vibration relaxation pathway in APN-CyI, so the ability of intersystem crossing (ISC) is restricted [33]. However, after being activated, the ICT process is recovered, therefore CyI-OH shows high singlet oxygen yield.

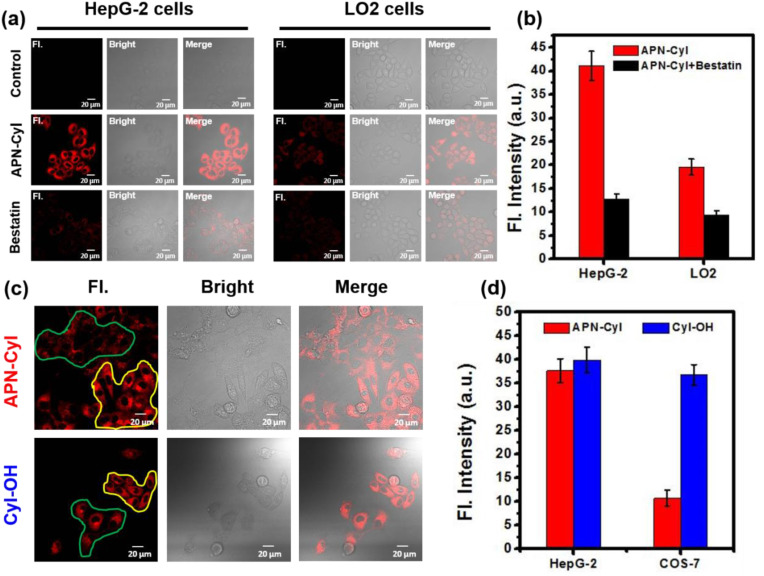

3.3. Cell imaging and cytotoxicity

Stimulated by the favorable response of APN-CyI in vitro, we tested its response in cancer and normal cells. Hepatoma carcinoma cells (HepG-2 cells), mice breast cancer cells (4T1 cells), normal liver cells (LO2 cells) and kidney fibroblasts cells (COS-7) were chosen to investigate the endogenous APN activity. After incubation with 2 μM APN-CyI for 120 min, a distinct NIR fluorescence signal was discovered in HepG-2 cells and 4T1 cells compared to LO2 cells, which certified the high level endogenous APN in HepG-2 cells and 4T1 cells. Furthermore, when the cells were pre-incubated with 50 μM bestatin for 60 min, the NIR fluorescence signal was inhibited obviously (Fig. 2 a and Fig. S5a). Fluorescence intensity was detected and the average fluorescence value was taken to quantify the results (Fig. 2b and Fig. S5b). Furthermore, to test the ability of APN-CyI to distinguish cancer cells from normal cells, a cell co-incubation experiment was conducted by employed HepG-2 cells and COS-7 cells due to the significant morphological differences. After incubation with APN-CyI, a significant fluorescence difference was observed and the average fluorescence value of each region was taken as a quantitative result, which illustrated that APN-CyI was activated only in cancer cells. As a contrast, the cells incubated with CyI-OH exhibited undifferentiated fluorescence intensity whether it was cancer cell or normal cell (Fig. 2c and d), since the photosensitizer in the activated state (CyI-OH) was always at “on” state in all cells. These facts demonstrated that APN-CyI could be used to monitor endogenous APN in living cells and distinguish cancer cells from normal cells.

Fig. 2.

(a) Fluorescence imaging of APN-CyI (2 μM) in HepG-2 cells and LO2 cells. The inhibition groups were pre-incubated with 50 μM bestatin. (b) Average fluorescence intensity of APN-CyI in various treated cells. (c) The co-incubation assays of HepG-2 cells (yellow region) and COS-7 cells (green region) with APN-CyI or CyI-OH. (d) Average fluorescence intensity of APN-CyI or CyI-OH in various cells. λex = 640 nm, λem = 700–800 nm. Scale bar = 20 μm. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

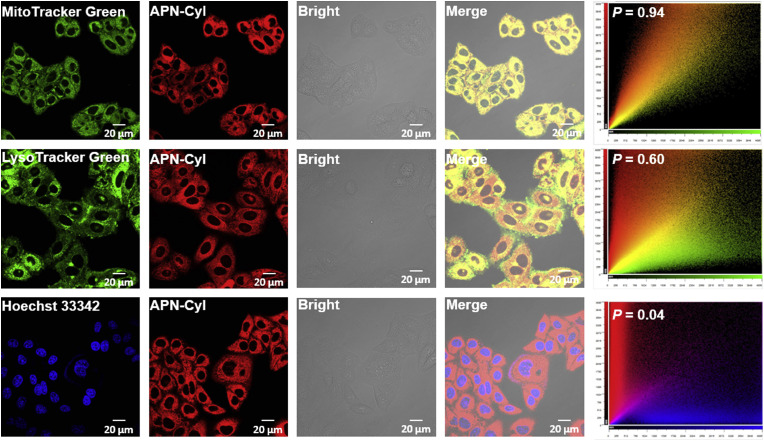

In order to explore the subcellular organelle distribution of APN-CyI in HepG-2 cells, various commercial subcellular organelle dyes including Hoechst 33342 (nucleus), Mito-Tracker Green (mitochondria) and Lyso-Tracker Green (lysosome) were co-incubated with APN-CyI (Fig. 3 ). The NIR fluorescence channel overlaid well with Mito-Tracker Green channel, leading to a high colocalization coefficient (P = 0.94). In contrast, a weak colocalization fluorescence signal was obtained between NIR fluorescence channel and Hoechst 33342 channel (P = 0.04) or Lyso-Tracker Green (P = 0.60). These facts indicated that the hydrolytic product CyI-OH was mainly distributed into mitochondria and we hypothesized the reason was that the intramolecular positive charge of CyI-OH was attracted by the negative membrane potential of the mitochondria and thus concentrated in it.

Fig. 3.

Subcellular localization experiments of APN-CyI in HepG-2 cells. MitoTracker Green channel was excited at 488 nm and collected at 500–550 nm. LysoTracker Green channel was excited at 488 nm and collected at 500–550 nm. Hoechst 33342 channel was excited at 405 nm and collected at 440–480 nm. APN-CyI channel was excited at 640 nm and collected at 700–800 nm. Scale bar = 20 μm. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

To verify whether the photosensitizer could produce singlet oxygen in living cells, HepG-2 cells were incubated with 2,7–dichlorodihydrofluorescin diacetate (DCFH-DA), a singlet oxygen inspection agent. After reacting with singlet oxygen, DCFH-DA would be oxidized to DCF (2,7-dichlorofluorescin) and thus producing strong fluorescence signal. As depicted in Fig. S6, an evident fluorescence signal was obtained in cells after being incubated with APN-CyI under a 660 nm irradiation for 5 min. In contrast, only APN-CyI or irradiation could not induce an obvious fluorescence enhancement. Moreover, when the cells were pretreated with N-acetylcysteine (NAC), the fluorescence signal was significantly reduced due to a redox reaction between NAC and singlet oxygen, which mightily demonstrated that the singlet oxygen could be triggered by APN-CyI in living cells.

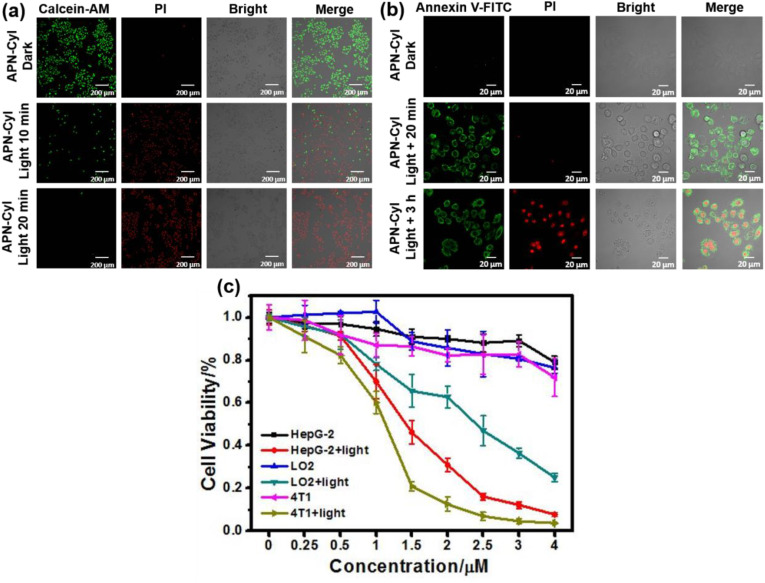

Encouraged by this result, cell viability imaging experiment was performed to test the cytotoxicity of APN-CyI. Herein, Calcein-AM and Propidium Iodide (PI) were employed to detect the cell viability with fluorescence imaging. Calcein-AM can be hydrolyzed by esterase of living cells to produce Calcein, resulting in a strong green fluorescence and PI can penetrate dead cell membranes and enter their nucleus to produce red fluorescence. As seen in Fig. 4 a, after being treated with APN-CyI for 120 min, almost no cytotoxicity was observed because of the intense fluorescence at Calcein-AM channel. Nevertheless, when the cells were exposed to NIR irradiation (660 nm, 20 mW) for 10 min, about 80% of cells were killed by singlet oxygen due to the strong fluorescence signal in PI channel. Furthermore, after being irradiated for 20 min, almost no cells could survive. These experiments proved that only triggered by the irradiation, APN-CyI could induce cell death by producing singlet oxygen.

Fig. 4.

(a) Fluorescence imaging of Calcein-AM and PI stained HepG-2 cells after different treatments. Calcein-AM: λex = 488 nm, λem = 500–550 nm. PI: λex = 561 nm, λem = 590–640 nm. Scale bar = 200 μm. (b) Annexin V – FITC and PI fluorescence imaging experiments in HepG-2 cells after different treatments. Annexin V – FITC: λex = 488 nm, λem = 500–550 nm. PI: λex = 561 nm, λem = 590–640 nm. Scale bar = 20 μm. (c) Cytotoxicity of APN-CyI in various cells under dark conditions or light conditions.

In order to further study the cell killing mode of APN-CyI, a cell apoptosis experiment was conducted by utilizing Annexin V-FITC and Propidium Iodide (PI) after an incubation with APN-CyI. In the early stage of apoptosis, the phosphatidylserine located on the inner surface of the cell membrane will be evaginated to the outer surface and bind with Annexin V-FITC specifically, hence result in an intense fluorescence on cytomembrane. As apoptosis proceeds, increased cell membrane permeability leads to PI entering the nucleus, producing red fluorescence. As depicted in Fig. 4b, neither APN-CyI nor irradiation could induce cell apoptosis. Nevertheless, when the cells were incubated for just 20 min after a photoinduction with APN-CyI, a distinct fluorescence was obtained at Annexin V-FITC channel rather than PI channel accompanied by the obvious changes in cell morphology, which was illustrated the appearance of apoptosis. Whereafter, after 3 h incubation, obvious fluorescence signals were detected at both Annexin V-FITC channel and PI channel, which indicated that APN-CyI could induce cell apoptosis under NIR irradiation. To further prove this result, flow cytometry assay was conducted on HepG-2 cells stained with Annexin V-FITC and PI. As shown in Fig. S7, compared with the other three control groups, only APN-CyI + Light group was observed significant fluorescence signal in first quartile and fourth quartile, demonstrated the positive signals in both Annexin V-FITC and PI channel, which powerfully testified the occurrence of cell apoptosis.

In order to further investigate the cytotoxicity of APN-CyI to different cells (HepG-2, 4T1 and LO2 cells), MTT method was used to evaluate it under dark and light conditions. As depicted in Fig. 4c, APN-CyI showed negligible cytotoxicity to both cancer cells (HepG-2 and 4T1 cells) and normal cells (LO2 cells) under dark conditions with a concentration less than 4 μM. However, obvious cytotoxicity was observed after 12 h of photo-induced incubation under a 660 nm irradiation (20 mW/cm2) for 20 min. More significantly, the photo-toxicity of APN-CyI to LO2 cells was overtly lower than that of HepG-2 and 4T1 cells, which could be explained by the fact that APN-CyI was activated by APN in cancer cells to produce CyI-OH, leading to an increase in singlet oxygen yield and cytotoxicity. It was worth noting that when the concentration of APN-CyI was about 2 μM, it had a considerable killing effect on cancer cells (cell viability = 15%) and relatively small damage to normal cells (cell viability = 70%). These experiment results verified that APN-CyI had an effective photo-toxicity on tumor cells while a comparatively mild toxicity on normal cells.

3.4. Tumor imaging and tumor suppression experiments on tumor mice model

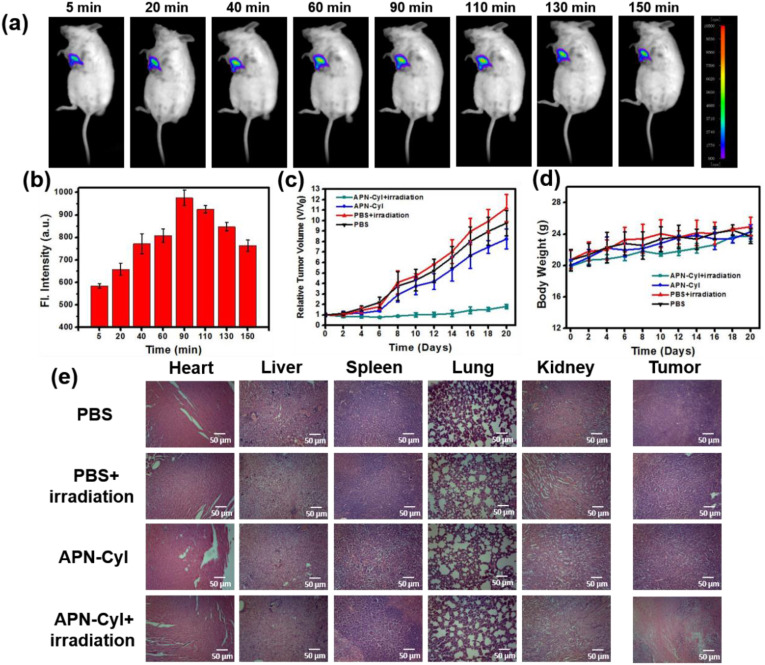

Inspired by the commendable experiment results of APN-CyI on imaging and PDT effect in vitro, in vivo imaging and tumor suppression experiments were conducted on 4TI-tumor Balb/c mice model. After intratumoral injection of APN-CyI, the fluorescence signal of 4TI-tumor Balb/c mice was measured by a NightOWL II LB983 small animal in vivo imaging system (λex = 665 nm, λem = 700–740 nm). As seen in Fig. 5 a, with the passage of time, the NIR fluorescence intensity at tumor site gradually increased and reached its maximum value at about 90 min, which suggested that our dye could be activated by APN in tumor site to enhance NIR fluorescence intensity. The same experiment was carried out three times in different mice, and the average fluorescence value was taken to quantify the results (Fig. 5b). The results suggested that APN-CyI could be utilized to detect APN by NIR fluorescence imaging in vivo.

Fig. 5.

(a) Fluorescence imaging of endogenous APN in tumor Balb/c mice in 150 min. The mice were intratumorally injected with 100 μL APN-CyI (100 μM) and were observed with excitation at 665 nm and emission at 700–740 nm. (N = 3) (b) Relative average fluorescence intensity of tumor site after intratumorally injection with 200 μL APN-CyI (100 μM) in 150 min. (c) Relative tumor volume after different treatments in 20 days. (d) The body weight of mice after different treatments in 20 days. (e) H&E staining of organs and tumors in different groups after 20 days.

Furthermore, we evaluated the photodynamic effect of APN-CyI in vivo through tumor inhibition experiment. Tumor volume and body weight were measured every two days after treatment within 20 days. As shown in Fig. 5c, whether the mice received 660 nm irradiation (100 mW/cm2, 20 min) or not, the tumor volume of PBS groups showed explosive growth in 20 days, which were 10-folds as large as when the treatment just started. In addition, the group treated with APN-CyI without irradiation showed a slightly tumor suppressive effect (8-folds) because of the low cytotoxicity of APN-CyI under dark conditions. However, compared with control groups, the PDT group showed superb tumor inhibition, which was embodied in the fact that the tumor volume barely increased during 20 days. The tumor pictures were shown in Fig. S8a, and the quality of tumors were measured, as depicted in Fig. S8b, the tumor quality of APN-CyI + Light group was significantly less than the other groups with an inhibitory rate of 77%. These facts strongly proved that the tumor could be inhibited by the PDT effect induced by APN-CyI under irradiation conditions. Moreover, the body weight of mice had no significant fluctuation in both control groups and PDT groups (Fig. 5d), which indicated that APN-CyI had negligible damage to the mice. To further attest this conclusion, the mice were sacrificed and dissected at the end of the treatment then the vital internal organs (heart, liver, spleen, lung and kidney) and tumors were washed with saline and kept in formalin. Subsequently, these organs were sectioned by paraffin method and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and observed through an optical microscope (Fig. 5e). No significant physiological or pathological tissue damage and inflammatory lesion were observed of organs and tumors in three control groups, indicating the low cytotoxicity of APN-CyI under dark conditions. Besides, organs in PDT group were not significantly different from those in control groups, however, conspicuous tumor tissue damage was observed in PDT group, which confirmed an ideal PDT effect of APN-CyI on solid tumors. All the results suggested that APN-CyI could be used as an effective photosensitizer to inhibit tumor growth under irradiation conditions.

4. Conclusions

In summary, we synthesized an iodine substituted NIR hemicyanine APN-activatable photosensitizer APN-CyI for tumor imaging and photodynamic therapy in this study. APN-CyI could be activated by APN via hydrolysis of alanine modified group to form CyI-OH, which displayed a distinct fluorescence emission at 717 nm and a dramatic improvement of singlet oxygen yield compared with APN-CyI. APN-CyI showed high selectivity and low detection limit (DL = 0.058 ng/mL) to APN and the response mechanism was confirmed by high resolution mass spectrometry and inhibition experiment. Cell imaging and cytotoxicity experiments confirmed that APN-CyI could distinguish cancer cells from normal cells and induce cells apoptosis under 660 nm light irradiation, moreover, APN-CyI had more phototoxicity to cancer cells compared with normal cells. The in vivo tumor imaging and tumor suppression experiment testified that APN-CyI were qualified to be an effective photosensitizer imaging intra-tumor APN and performing photodynamic therapy for solid tumors after activation. To sum up, this study developed a novel activatable photosensitizer for APN imaging and photodynamic therapy in vitro and in vivo. We expect this work to provide a reference for the development of safer and more effective anti-cancer drugs in the future.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Xiao Zhou: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing - original draft, Visualization. Haidong Li: Conceptualization, Methodology. Chao Shi: Formal analysis, Investigation. Feng Xu: Methodology, Formal analysis. Zhen Zhang: Formal analysis, Investigation. Qichao Yao: Conceptualization, Methodology. He Ma: Methodology, Formal analysis. Wen Sun: Formal analysis, Investigation, Supervision, Resources. Kun Shao: Resources, Supervision, Funding acquisition. Jianjun Du: Resources, Supervision, Funding acquisition. Saran Long: Resources, Supervision, Project administration, Writing - review & editing. Jiangli Fan: Resources, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Project administration. Jingyun Wang: Resources, Supervision, Funding acquisition. Xiaojun Peng: Resources, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Writing - review & editing, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (project 21421005) and NSFC-Liaoning United Fund (U1608222 and U1908202).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.120089.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Dolmans D.E.J.G., Fukumura D., Jain R.K. Photodynamic therapy for cancer. Nat. Rev. Canc. 2003;3:380–387. doi: 10.1038/nrc1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Celli J.P., Spring B.Q., Rizvi I., Evans C.L., Samkoe K.S., Verma S., Pogue B.W., Hasan T. Imaging and photodynamic therapy: mechanisms, monitoring, and optimization. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:2795–2838. doi: 10.1021/cr900300p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li X., Lee S., Yoon J. Supramolecular photosensitizers rejuvenate photodynamic therapy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018;47:1174–1188. doi: 10.1039/c7cs00594f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luby B.M., Walsh C.D., Zheng G. Advanced photosensitizer activation strategies for smarter photodynamic therapy beacons. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019;58:2558–2569. doi: 10.1002/anie.201805246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li M., Xiong T., Du J., Tian R., Xiao M., Guo L., Long S., Fan J., Sun W., Shao K., Song X., Foley J.W., Peng X. Superoxide radical photogenerator with amplification effect: surmounting the achilles' heels of photodynamic oncotherapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:2695–2702. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b13141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robertson C.A., Evans D.H., Abrahamse H. Photodynamic therapy (PDT): a short review on cellular mechanisms and cancer research applications for PDT. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2009;96:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kwiatkowski S., Knap B., Przystupski D., Saczko J., Kędzierska E., Knap-Czop K., Kotlińska J., Michel O., Kotowski K., Kulbacka J. Photodynamic therapy mechanisms, photosensitizers and combinations. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018;106:1098–1107. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li M., Long S., Kang Y., Guo L., Wang J., Fan J., Du J., Peng X. De novo design of phototheranostic sensitizers based on structure-inherent targeting for enhanced cancer ablation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:15820–15826. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b09117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McDonnell S.O., Hall M.J., Allen L.T., Byrne A., Gallagher W.M., O'Shea D.F. Supramolecular photonic therapeutic agents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:16360–16361. doi: 10.1021/ja0553497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Z., Wang J., Chen J., Lei W., Wang X., Zhang B. Hypocrellin B doped and pH-responsive silica nanoparticles for photodynamic therapy. Sci. China Chem. 2010;53:1994–1999. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao X., Li Y., Jin D., Xing Y., Yan X., Chen L. A near-infrared multifunctional fluorescent probe with an inherent tumor-targeting property for bioimaging. Chem. Commun. 2015;51:11721–11724. doi: 10.1039/c5cc03878b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shi C., Li M., Zhang Z., Yao Q., Shao K., Xu F., Xu N., Li H., Fan J., Sun W., Du J., Long S., Wang J., Peng X. Catalase-based liposomal for reversing immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment and enhanced cancer chemo-photodynamic therapy. Biomaterials. 2020;233:119755. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.119755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu J., Xu L., Wang C., Yang R., Zhuang Q., Han X., Dong Z., Zhu W., Peng R., Liu Z. Near-infrared-triggered photodynamic therapy with multitasking upconversion nanoparticles in combination with checkpoint blockade for immunotherapy of colorectal cancer. ACS Nano. 2017;11:4463–4474. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b00715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi H.S., Gibbs S.L., Lee J.H., Kim S.H., Ashitate Y., Liu F., Hyun H., Park G., Xie Y., Bae S., Henary M., Frangioni J.V. Targeted zwitterionic near-infrared fluorophores for improved optical imaging. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:148–153. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang L., Li Z., Zhao Y., Zhang Y., Wu S., Zhao J., Han G. Ultralow-power near infrared lamp light operable targeted organic nanoparticle photodynamic therapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:14586–14591. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b05390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang P., Steelant W., Kumar M., Scholfield M. Versatile photosensitizers for photodynamic therapy at infrared excitation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:4526–4527. doi: 10.1021/ja0700707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu X., Zhu W. Stability enhancement of fluorophores for lighting up practical application in bioimaging. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015;44:4179–4184. doi: 10.1039/c4cs00152d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang J., Jiang C., Figueiró Longo J.P., Azevedo R.B., Zhang H., Muehlmann L.A. An updated overview on the development of new photosensitizers for anticancer photodynamic therapy. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 2018;8:137–146. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2017.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li M., Xia J., Tian R., Wang J., Fan J., Du J., Long S., Song X., Foley J.W., Peng X. Near-infrared light-initiated molecular superoxide radical generator: rejuvenating photodynamic therapy against hypoxic tumors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:14851–14859. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b08658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kennedy J.C., Pottier R.H. New trends in photobiology: endogenous protoporphyrin IX, a clinically useful photosensitizer for photodynamic therapy. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 1992;14:275–292. doi: 10.1016/1011-1344(92)85108-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Han K., Wang S., Lei Q., Zhu J., Zhang X. Ratiometric biosensor for aggregation-induced emission-guided precise photodynamic therapy. ACS Nano. 2015;9:10268–10277. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b04243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lovell J.F., Liu T.W.B., Chen J., Zheng G. Activatable photosensitizers for imaging and therapy. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:2839–2857. doi: 10.1021/cr900236h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu W., Shao X., Zhao J., Wu M. Controllable photodynamic therapy implemented by regulating singlet oxygen efficiency. Adv. Sci. 2017;4:1700113. doi: 10.1002/advs.201700113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu H., Hu X., Li K., Liu Y., Rong Q., Zhu L., Yuan L., Qu F., Zhang X., Tan W. A mitochondrial-targeted prodrug for NIR imaging guided and synergetic NIR photodynamic-chemo cancer therapy. Chem. Sci. 2017;8:7689–7695. doi: 10.1039/c7sc03454g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou J., Xue C.C., Hou Y.H., Li M.H., Hu Y., Chen Q.F., Li Y.N., Li K., Song G.B., Cai K.Y., Luo Z. Oxygenated theranostic nanoplatforms with intracellular agglomeration behavior for improving the treatment efficacy of hypoxic tumors. Biomaterials. 2019;197:129–145. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang J., Li W., Luo L.H., Jiang M.S., Zhu C.Q., Qin B., Yin H., Yuan X.L., Yin X.Y., Zhang J.L., Luo Z.Y., You J. Hypoxic tumor therapy by hemoglobin-mediated drug delivery and reversal of hypoxia-induced chemoresistance. Biomaterials. 2018;182:145–156. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li H., Yao Q., Xu F., Xu N., Duan R., Long S., Fan J., Du J., Wang J., Peng X. Imaging γ-Glutamyltranspeptidase for tumor identification and resection guidance via enzyme-triggered fluorescent probe. Biomaterials. 2018;179:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bian Y., Li M., Fan J., Du J., Long S., Peng X. A proton-activatable aminated-chrysophanol sensitizer for photodynamic therapy. Dyes Pigments. 2017;147:476–483. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang Z., Lee J.H., Jeon H.M., Han J.H., Park N., He Y., Lee H., Hong K.S., Kang C., Kim J.S. Folate-based near-infrared fluorescent theranostic gemcitabine delivery. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:11657–11662. doi: 10.1021/ja405372k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen H., Tian J., He W., Guo Z. H2O2-Activatable and O2-evolving nanoparticles for highly efficient and selective photodynamic therapy against hypoxic tumor cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:1539–1547. doi: 10.1021/ja511420n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu X., Sun X., Guo Z., Tang J., Shen Y., James T.D., Tian H., Zhu W. In vivo and in situ tracking cancer chemotherapy by highly photostable NIR fluorescent theranostic prodrug. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:3579–3588. doi: 10.1021/ja412380j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li H., Wang P., Deng Y., Zeng M., Tang Y., Zhu W., Cheng Y. Combination of active targeting, enzyme-triggered release and fluorescent dye into gold nanoclusters for endomicroscopy-guided photothermal/photodynamic therapy to pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Biomaterials. 2017;139:30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu F., Li H., Yao Q., Ge H., Fan J., Sun W., Wang J., Peng X. Hypoxia-activated NIR photosensitizer anchoring in the mitochondria for photodynamic therapy. Chem. Sci. 2019;10:10586–10594. doi: 10.1039/c9sc03355f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shi H., Sun W., Liu C., Gu G., Ma B., Si W., Fu N., Zhang Q., Huang W., Dong X. Tumor-targeting, enzyme-activated nanoparticles for simultaneous cancer diagnosis and photodynamic therapy. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2016;4:113–120. doi: 10.1039/c5tb02041g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen L., Lin Y., Peng G., Li F. Structural basis for multifunctional roles of mammalian aminopeptidase N. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012;109:17966. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210123109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cui S., Qu X., Gao Z., Zhang Y., Zhang X., Zhao C., Xu W., Li Q., Han J. Targeting aminopeptidase N (APN/CD13) with cyclic-imide peptidomimetics derivative CIP-13F inhibits the growth of human ovarian carcinoma cells. Canc. Lett. 2010;292:153–162. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shim J.S., Kim J.H., Cho H.Y., Yum Y.N., Kim S.H., Park H., Shim B.S., Choi S.H., Kwon H.J. Irreversible inhibition of CD13/aminopeptidase N by the antiangiogenic agent curcumin. Chem. Biol. 2003;10:695–704. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(03)00169-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saitoh Y., Koizumi K., Minami T., Sekine K., Sakurai H., Saiki I. A derivative of aminopeptidase inhibitor (BE15) has a dual inhibitory effect of invasion and motility on tumor and endothelial cells. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2006;29:709–712. doi: 10.1248/bpb.29.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aozuka Y., Koizumi K., Saitoh Y., Ueda Y., Sakurai H., Saiki I. Anti-tumor angiogenesis effect of aminopeptidase inhibitor bestatin against B16-BL6 melanoma cells orthotopically implanted into syngeneic mice. Canc. Lett. 2004;216:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hata R., Nonaka H., Takakusagi Y., Ichikawa K., Sando S. Design of a hyperpolarized molecular probe for detection of aminopeptidase N activity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:1765–1768. doi: 10.1002/anie.201509457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Terauchi M., Kajiyama H., Shibata K., Ino K., Nawa A., Mizutani S., Kikkawa F. Inhibition of APN/CD13 leads to suppressed progressive potential in ovarian carcinoma cells. BMC Canc. 2007;7:140. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wickström M., Larsson R., Nygren P., Gullbo J. Aminopeptidase N (CD13) as a target for cancer chemotherapy. Canc. Sci. 2011;102:501–508. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01826.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.He X., Hu Y., Shi W., Li X., Ma H. Design, synthesis and application of a near-infrared fluorescent probe for in vivo imaging of aminopeptidase N. Chem. Commun. 2017;53:9438–9441. doi: 10.1039/c7cc05142e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li H., Li Y., Yao Q., Fan J., Sun W., Long S., Shao K., Du J., Wang J., Peng X. In situ imaging of aminopeptidase N activity in hepatocellular carcinoma: a migration model for tumour using an activatable two-photon NIR fluorescent probe. Chem. Sci. 2019;10:1619–1625. doi: 10.1039/c8sc04685a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li H., Yao Q., Sun W., Shao K., Lu Y., Chung J., Kim D., Fan J., Long S., Du J., Li Y., Wang J., Yoon J., Peng X. Aminopeptidase N activatable fluorescent probe for tracking metastatic cancer and image-guided surgery via in situ spraying. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020;142:6381–6389. doi: 10.1021/jacs.0c01365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.He X., Xu Y., Shi W., Ma H. Ultrasensitive detection of aminopeptidase N activity in urine and cells with a ratiometric fluorescence probe. Anal. Chem. 2017;89:3217–3221. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yuan L., Lin W., Zhao S., Gao W., Chen B., He L., Zhu S. A unique approach to development of near-infrared fluorescent sensors for in vivo imaging. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:13510–13523. doi: 10.1021/ja305802v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Atchison J., Kamila S., Nesbitt H., Logan K.A., Nicholas D.M., Fowley C., Davis J., Callan B., McHale A.P., Callan J.F. Iodinated cyanine dyes: a new class of sensitisers for use in NIR activated photodynamic therapy (PDT) Chem. Commun. 2017;53:2009–2012. doi: 10.1039/c6cc09624g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.