Abstract

Objective(s):

Clostridioides (Clostridium) difficile infection as a healthcare-associated infection can cause life-threatening infectious diarrhea in hospitalized patients. The aim of this study was to investigate the toxin profiles and antimicrobial resistance patterns of C. difficile isolates obtained from hospitalized patients in Shiraz, Iran.

Materials and Methods:

This study was performed on 45 toxigenic C. difficile isolates. Determination of toxin profiles was done using polymerase chain reaction method. Antimicrobial susceptibility to vancomycin, metronidazole, clindamycin, tetracycline, moxifloxacin, and chloramphenicol was determined by the agar dilution method. The genes encoding antibiotic resistance were detected by the standard procedures.

Results:

The most frequent toxin profile was tcdA+, tcdB+, cdtAˉ, cdtBˉ (82.2%), and only one isolate harboured all toxin associated genes (tcdA+, tcdB+, cdtA+, cdtB+) (2.2%). The genes encoding CDT (binary toxin) were also found in six (13.3%) isolates. Resistance to tetracycline, clindamycin and moxifloxacin was observed in 66.7%, 60% and 42.2% of the isolates, respectively. None of the strains showed resistance to other antibiotics. The distribution of the ermB gene (the gene encoding resistance to clindamycin) was 57.8% and the tetM and tetW genes (the genes encoding resistance to tetracycline) were found in 62.2% and 13.3% of the isolates, respectively. The substitutions Thr82 to Ile in GyrA and Asp426 to Asn in GyrB were seen in moxifloxacin resistant isolates.

Conclusion:

Our data contributes to the present understanding of virulence and resistance traits amongst the isolates. Infection control strategies should be implemented carefully in order to curb the dissemination of C. difficile strains in hospital.

Key Words: Antibiotic resistance, CDT, Clostridioides (Clostridium) – difficile, C. difficile infection, Toxins

Introduction

Clostridioides difficile (formerly Clostridium difficile) is a Gram-positive rod-shaped, spore-forming, strictly anaerobic bacterium and the causative agent of C. difficile infection (CDI) (1). CDI, as a serious healthcare-associated infection, can cause life-threatening infectious diarrhea in hospitalized patients (2). Disruption of the intestinal microbiome induced by antibiotics is the major risk factor for the development of CDI (3).

Toxins secreted by the toxigenic strains are responsible for the occurrence of the disease. C. difficile toxins A and B are the main virulence factors of the pathogens, encoded by tcdA and tcdB genes, respectively. They are located on the pathogenicity locus (PaLoc). Toxin A as an enterotoxin and Toxin B with cytotoxic activity alter the actin cytoskeleton and cause cell rounding, disruption of tight junctions, and intestinal function failure (3-5).

Besides toxins A and B, some of C. difficile strains express a binary toxin (CDT). This additional virulence factor belongs to the ADP-ribosyltransferase family and consists of enzymatic (CDTa) and binding components (CDTb) (3-5). The cdtA and cdtB genes encode the CDT toxin that induces actin depolymerization in the cytoskeleton, leading to an increase in the bacterial adherence to colonic epithelium and severity of infection (5, 6).

The risk of CDI is increased if C. difficile is resistant to the antibiotics used. Although C. difficile is usually susceptible to metronidazole and vancomycin (the first line of antibiotics used for the treatment of CDI), resistance or decreased susceptibility has been reported in the literature (7, 8).

Mechanisms of resistance to the members of macrolide–lincosamide–streptogramin B (MLSB) group include ribosomal modification, efflux pumps, and drug inactivation. Resistance to MLSB in C. difficile is mainly associated with the erm genes (especially ermB) located on a mobile genetic element (7, 9, 10). Other probable mechanisms such as efflux could have caused this type of resistance (7).

In C. difficile, resistance mechanisms to other antimicrobial agents such as tetracyclines, fluoroquinolones and chloramphenicol were also characterized previously. The tet and catD genes confer tetracyclines and chloramphenicol resistance, respectively. Different mutations in gyrA and gyrB are also associated with quinolones resistance (7, 10, 11).

To the best of our knowledge, there are few data regarding CDI in Iran. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to evaluate the toxin profiles and antimicrobial resistance patterns of C. difficile isolates obtained from hospitalized patients with CDI in Shiraz, southwestern Iran.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial isolates

This study was performed on 45 toxigenic C. difficile isolates obtained from fecal specimens of patients with antibiotic-associated diarrhea, hospitalized in Nemazee Hospital (The main hospital affiliated to Shiraz University of Medical Sciences) and Amir Oncology Hospital from October 2017 to June 2018 (12). Only one isolate per patient was included. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (Register code: IR.SUMS.REC.1397.114).

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), diarrhea was defined as more than 3 loose and watery stools during a 24 hr period or fewer hrs (13). Also, based on the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), CDI was defined as a patient with diarrhea whose stool takes the container shape, and is positive for toxigenic (toxin A and/or toxin B) C. difficile without any other etiology (14). Identification of the isolates was performed based on Gram staining, odor and colony characteristics on cycloserine-cefoxitin fructose agar (CCFA) plate. The tpi housekeeping gene (triose phosphate isomerase) was targeted by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), using specific primers for molecular confirmation (Table 1) (15). The PCR protocol consisted of a pre-denaturation step at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of 60 sec at 95 °C, 45 sec at 53 °C and 50 sec at 72 °C. A final extension step was performed at 72°C for 5 min.

Table 1.

Primers used in the study

| Gene | Function | Primer sequence (5'- 3') | Product size (bp) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| tpi | Triose phosphate isomerase (housekeeping) | F: AAAGAAGCTACTAAGGGTACAAA R: CATAATATTGGGTCTATTCCTAC |

230 | |

| tcdA | Toxin A | F: AGATTCCTATATTTACATGACAATAT R: GTATCAGGCATAAAGTAATATACTTT |

369 | |

| tcdB | Toxin B | F: GGAAAAGAGAATGGTTTTATTAA R: ATCTTTAGTTATAACTTTGACATCTTT |

160 | |

| cdtA | Binary toxin | F: TGAACCTGGAAAAGGTGATG R: AGGATTATTTACTGGACCATTTG |

375 | |

| cdtB | Binary toxin | F: CTTAATGCAAGTAAATACTGAG R: AACGGATCTCTTGCTTCAGTC |

510 | |

| nim | Metronidazole resistance | F: ATGTTCAGAGAAATGCGGCGTAAGCG R: GCTTCCTTGCCTGTCATGTGCTC |

458 | |

| ermA | MLSB resistance | F: TATCTTATCGTTGAGAAGGGATT R: CTACACTTGGCTTAGGATGAAA |

139 | |

| ermB | MLSB resistance | F: CTCAAAACTTTTTAACGAGTG R: CCTCCCGTTAAATAATAGATA |

711 | |

| ermC | MLSB resistance | F: CTTGTTGATCACGATAATTTCC R: ATCTTTTAGCAAACCCGTATTC |

190 | |

| tetM | Tetracycline resistance | F: TGGAATTGATTTATCAACGG R: TTCCAACCATACAATCCTTG |

1000 | |

| tetW | Tetracycline resistance | F: CATCTCTGTGATTTTCAGCTTTTCTCTCCC R: AGTCTGTTCGGGATAAGCTCTCCGCCG |

457 | |

| catD | Chloramphenicol resistance | F: ATACAGCATGACCGTTAAAG R: ATGTGAAATCCGTCACATAC |

500 | |

| gyrA | Quinolone resistance (mutation) | F: AATGAGTGTTATAGCTGGACG R: TCTTTTAACGACTCATCAAAGTT |

390 | |

| gyrB | Quinolone resistance (mutation) | F: AGTTGATGAACTGGGGTCTT R: TCAAAATCTTCTCCAATACCA |

390 |

MLSB: macrolide–lincosamide–streptogramin B

Determination of toxin profile

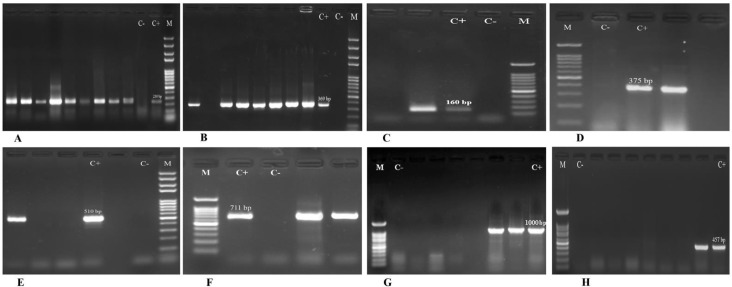

Genomic DNA was extracted from freshly grown colonies, using the commercial DNA extraction kits (GeneAll, Korea) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. PCR was carried out for detection of the genes encoding toxin A and toxin B (tcdA and tcdB) and binary toxin CDT (cdtA and cdtB) by specific primers (Table 1) (15, 16). The PCR reactions consisted of a pre-denaturation step at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of 60 sec at 95 °C, 45 sec at 51 °C (for tcdA), 50 °C (for tcdB), 53 °C (for cdtA and cdtB), and 50 sec at 72 °C. A final extension step was performed at 72 °C for 5 min. The PCR products were separated by electrophoresis in 1% agarose gels with 1 X TAE (Tris/Acetate/EDTA) buffer, stained with safe stain load dye (CinnaGen Co., Iran) and visualized under ultraviolet (UV) illumination (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of PCR products for tpi (A), tcdA (B), tcdB (C), cdtA (D), cdtB (E), ermB (F), tetM (G) and tetW (H) genes. Lane M: 100 bp DNA size marker; Lane C-: negative control; Lane C+: positive control

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of six antibiotics including vancomycin, metronidazole, clindamycin, tetracycline, moxifloxacin, and chloramphenicol were determined by the agar dilution method according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) (17). Brucella agar supplemented with hemin (5 µg/ml), vitamin K1 (10 µg/ml), and 5% sheep blood was used for the tests. C. difficile ATCC 700057 was used as a control strain for the susceptibility tests. Antibiotic resistance and susceptibility were determined using the breakpoints defined by the CLSI (for metronidazole, clindamycin, tetracycline, moxifloxacin, and chloramphenicol) and the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) (for vancomycin) (18).

Detection of antimicrobial resistance genes and sequencing

The genes encoding resistance to metronidazole (nim), MLSB (ermA, ermB, ermC), tetracycline (tetM, tetW), and chloramphenicol (catD) were detected by PCR method using specific primers (Table 1) (11, 19, 20). The PCR products were separated and visualized, as mentioned above (Figure 1). The quinolone resistance-determining-regions (QRDRs) of gyrA and gyrB were also amplified, as described previously (Table 1) (21). The amplicons were sequenced by the ABI capillary system (Macrogen Research, Seoul, Korea). The sequences were aligned with the reference sequence of C. difficile 630 (NCBI Reference Sequence: NC_009089.1), using online BLAST software (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi).

Statistical analysis

The analysis was performed using SPSSTM software, version 21.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA). The distribution of MLSB resistance genes among clindamycin non-susceptible and susceptible isolates was calculated by Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests for each gene. The prevalence of tetracycline resistance genes among tetracycline non-susceptible and susceptible isolates was also calculated by the above mentioned tests. A P-value of ≤ 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Gram-positive bacilli, with subterminal endospores were observed in Gram-stained smears. Their yellow colonies had horse stable odor and chartreuse fluorescence under the UV light. Moreover, the tpi gene was found in 100% of the isolates and they were molecularly confirmed. All the isolates possessed at least one toxin associated gene. The genes encoding binary toxin were found in six (13.3%) isolates. The cdtA was present in five (11.1%) isolates and only one strain carried both cdtA and cdtB genes (2.2%). As shown in Table 2, predominant toxin profile was tcdA+, tcdB+, cdtAˉ, cdtBˉ (82.2%) followed by tcdA+, tcdB+, cdtA+, cdtBˉ (11.1%), tcdAˉ, tcdB+, cdtAˉ, cdtBˉ (4.5%), and tcdA+, tcdB+, cdtA+, cdtB+ (2.2%).

Table 2.

Toxin profiles and antimicrobial resistance patterns of Clostridioides (Clostridium) difficile

| No. of isolates | Underlying disease |

Toxin profile

( tcdA, tcdB / CDT) |

Resistance pattern | Resistance genes | GyrA/GyrB substitution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gastrointestinal diseases (15) |

tcdA, tcdB | CD, TET | ermB, tetM | - |

| 2 | tcdA, tcdB | CD, MXF | ermB | GyrA (Thr82→Ile) | |

| 3 | tcdA, tcdB | CD, TET, MXF | ermB, tetM | GyrA (Thr82→Ile) | |

| 4 | tcdA, tcdB / cdtA | CD, TET, MXF | ermB, tetM | GyrB (Asp426→Asn) | |

| 5 | tcdA, tcdB | CD, MXF | - | GyrA (Thr82→Ile) | |

| 6 | tcdA, tcdB | TET | tetM | - | |

| 7 | tcdA, tcdB | CD, TET | ermB, tetM | - | |

| 8 | tcdA, tcdB | TET, MXF | tetW | GyrA (Thr82→Ile) | |

| 9 | tcdA, tcdB | CD, MXF | ermB | GyrA (Thr82→Ile) | |

| 10 | tcdA, tcdB | TET, MXF | tetM, tetW | GyrA (Thr82→Ile) | |

| 11 | tcdA, tcdB | - | - | - | |

| 12 | tcdA, tcdB / cdtA | TET | tetM | - | |

| 13 | tcdA, tcdB / cdtA | TET, MXF | tetM | GyrA (Thr82→Ile) | |

| 14 | tcdA, tcdB | CD, MXF | ermB | GyrA (Thr82→Ile) | |

| 15 | tcdA, tcdB | CD, TET, MXF | ermB, tetM | GyrA (Thr82→Ile) | |

| 16 | Hematologic disorders (10) |

tcdA, tcdB / cdtA | CD | - | - |

| 17 | tcdA, tcdB | CD | ermB | - | |

| 18 | tcdA, tcdB | CD, TET | ermB, tetM, tetW | - | |

| 19 | tcdA, tcdB | CD, TET, MXF | ermB, tetM | GyrB (Asp426→Asn) | |

| 20 | tcdA, tcdB | CD, TET | ermB, tetM | - | |

| 21 | tcdA, tcdB | CD, TET | ermB, tetM | - | |

| 22 | tcdA, tcdB | CD | ermB | - | |

| 23 | tcdA, tcdB | CD, TET | ermB, tetM | - | |

| 24 | tcdA, tcdB | TET, MXF | ermB, tetM | GyrA (Thr82→Ile) | |

| 25 | tcdA, tcdB | CD, TET, MXF | ermB, tetM | GyrA (Thr82→Ile) | |

| 26 | Liver diseases (6) |

tcdA, tcdB | TET | tetM, tetW | - |

| 27 | tcdA, tcdB | CD | ermB | - | |

| 28 | tcdA, tcdB / cdtA | CD, TET | ermB, tetM | - | |

| 29 | tcdA, tcdB, | TET | ermB, tetM | - | |

| 30 | tcdA, tcdB | TET, MXF | tetM | GyrA (Thr82→Ile) | |

| 31 | tcdA, tcdB / cdtA, cdtB | CD, TET, MXF | ermB, tetM | GyrA (Thr82→Ile) | |

| 32 | Kidney diseases (5) |

tcdA, tcdB | CD, MXF | ermB | GyrB (Asp426→Asn) |

| 33 | tcdA, tcdB | CD, TET | tetM | - | |

| 34 | tcdB | CD, TET | tetM | - | |

| 35 | tcdA, tcdB | TET, MXF | tetM | GyrA (Thr82→Ile) | |

| 36 | tcdA, tcdB | TET | ermB, tetM, tetW | - | |

| 37 | Metabolic disorders (4) |

tcdA, tcdB | - | - | - |

| 38 | tcdA, tcdB | - | - | - | |

| 39 | tcdA, tcdB | TET | tetW | - | |

| 40 | tcdB | CD, TET | ermB, tetM | - | |

| 41 | Pneumonia (2) |

tcdA, tcdB | MXF | - | GyrA (Thr82→Ile) |

| 42 | tcdA, tcdB | CD, MXF | ermB | GyrB (Asp426→Asn) | |

| 43 | Eye diseases (2) |

tcdA, tcdB | TET | tetM | - |

| 44 | tcdA, tcdB | - | - | - | |

| 45 | Osteosarcoma (1) |

tcdA, tcdB | CD, TET | ermB, tetM | - |

CD: Clindamycin; TET: Tetracycline; MXF: Moxifloxacin

According to MIC results, resistance to tetracycline (MIC ≥16 µg/ml), clindamycin (MIC ≥8 µg/ml) and moxifloxacin (MIC ≥8 µg/ml) was observed in 30 (66.7%), 27 (60%) and 19 (42.2%) isolates, respectively (Table 3). None of the strains showed resistance to other antibiotics tested. The details of MIC results, MIC50 and MIC90 of the tested antibiotics against the isolates are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of the tested antibiotics against Clostridioides (Clostridium) difficile isolates

| Antibiotic |

MIC (µg/mL)

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.125 | 0.19 | 0.25 | 0.38 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 1 | 1.5 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | ≥32 | |

| Vancomycin | 4 | 10 | 8 | 9 | 3 | 7 | 4 | ||||||

| Metronidazole | 12 | 16 | 7 | 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| Clindamycin | 3 | 12 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 21 | |||||||

| Tetracycline | 2 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 11 | 19 | ||||||

| Moxifloxacin | 3 | 5 | 14 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 7 | ||||||

| Chloramphenicol | 8 | 15 | 11 | 6 | 2 | 3 | |||||||

MIC: Minimum inhibitory concentration; underlined: MIC50; boldface: MIC90

The distribution of the ermB gene was 57.8% and the ermA and ermC genes were not detected amongst the isolates. The presence of ermB gene in clindamycin non-susceptible isolates was more than susceptible isolates, significantly (P<0.001). Also, the frequency of tetM and tetW genes was 62.2% and 13.3%, respectively. The tetM gene was more prevalent in tetracycline non-susceptible in comparison to susceptible isolates with a significant correlation (P<0.001). However, other resistance-related genes including nim and catD were not found in any of the isolates. Sequencing analysis of gyrA and gyrB revealed that of 19 moxifloxacin resistant strains, 15 isolates possessed (Thr82→Ile) substitution in GyrA, and four isolates had (Asp426→Asn) substitution in GyrB (Table 2).

Discussion

In the present study, toxin profiles and antimicrobial susceptibilities of CDI causative isolates were investigated. All the isolates were toxigenic and carried at least one toxin associated gene (Table 2). Similarly, a high distribution of the genes encoding toxins A and B amongst clinical C. difficile isolates was reported in various studies (1, 5, 22-24). The main role of these virulence factors to cause CDI had been well characterized (3, 4).

Our findings indicated that one (2.2%) isolate had both CDT related genes (cdtA and cdtB) and five (11.1%) isolates harboured cdtA gene without cdtB (Table 2). Clinical C. difficile isolates with only one of the two components gene (cdtA or cdtB) have been reported from other Asian counties (9, 25). It seems that this pattern of binary toxin genes is prevalent in our geographical region. Similar to our findings, in the other study from Iran, these two genes were detected in a CDT positive isolate simultaneously (26). Presence and expression of binary toxin genes create synergy with other toxins and increase the pathogenicity of C. difficile (25, 27).

According to our results, the most frequent toxin profile was A+ B+ CDT ¯ . Although a different pattern was published as the major genotype from Kerman, Iran in 2017 (26), but A+ B+ CDT ¯ profile was predominant in the several studies around the world (5, 28-32).

MICs results showed that all the isolates were completely inhibited by vancomycin and metronidazole (Table 3). Various studies showed the same results and these agents were effective against their isolates (1, 5, 9, 24, 33-37). Although vancomycin and metronidazole were efficient choices against CDI in our study, however, their prescription should be under control for prevention of the emergence of resistant strains. In recent years, vancomycin and/or metronidazole resistance has been observed in Iran and the other countries (8, 32, 38, 39). These data suggest that CDI therapy by the mentioned antibiotics could be problematic in the future. In the current study, chloramphenicol resistance and its related gene (catD) were not found amongst the isolates (MICs ≤ 16) (Table 3). In contrast, resistance to this antibiotic was described in previous studies (11, 32, 35, 40, 41). The rate of chloramphenicol prescription in our investigated hospitals is very low. Therefore, it can justify lack of chloramphenicol resistance.

We found that 30 (66.7%) C. difficile isolates displayed tetracycline resistance (MIC ≥16) (Table 3). They carried at least one tetM or tetW gene and four strains had both genes (Table 2). Resistance to tetracycline was shown in several studies (10, 20, 31, 35, 37, 38). Our findings were in line with the previous report that showed that the predominant tet gene in C. difficile was tetM and the second frequent one was tetW (20). However, in a study conducted by Abuderman et al., only tetM was observed amongst the resistant C. difficile isolates (9). One of the reasons for notable rates of tetracycline resistance and tet genes distribution is the presence of tet cluster of genes on transferable mobile elements (7, 8).

The percentage of the isolates resistant to clindamycin (MIC ≥8) and moxifloxacin (MIC ≥8) was 60% (27/45) and 42.2% (19/45), respectively. The ermB gene was found in 26 (57.8%) isolates and ermA and ermC genes were not detected amongst any of the strains. As mentioned in several studies, ermB had a key role in MLSB resistance of C. difficile isolates (9-11, 20, 42). According to our findings, some ermB-negative strains were clindamycin resistant (Table 2). Other mechanisms such as efflux pumps or cfr gene may be responsible for resistance. The cfr gene, which encodes an RNA methyltransferase, can confer MLSB resistance in erm-negative bacteria (8). On the other hand, three susceptible isolates carried the ermB gene. This sensitivity is probably related to the insufficient expression of the gene.

Sequencing analysis revealed that all moxifloxacin resistant isolates possessed substitution in GyrA or GyrB (Table 2). The substitution Thr82 to Ile in GyrA was found in the majority of the resistant strains (15/19). Furthermore, substitution Asp426 to Asn in GyrB also accounted for resistance to other moxifloxacin resistant isolates (4/19). The same substitution in GyrA was remarkable amino acid changes in previous studies (21, 43).

Conclusion

The most frequent toxin profile was tcdA+, tcdB+, cdtAˉ, cdtBˉ (82.2%), and only one isolate harboured all toxin associated genes (tcdA+, tcdB+, cdtA+, cdtB+) (2.2%). The genes encoding binary toxin were also found in six (13.3%) strains. Only one strain carried both cdtA and cdtB genes (2.2%). Resistance to tetracycline, clindamycin and moxifloxacin was observed in 30 (66.7%), 27 (60%) and 19 (42.2%) isolates, respectively. Metronidazole, vancomycin and chloramphenicol resistance was not seen amongst the isolates. The distribution of the ermB gene was 57.8% and the ermA and ermC genes were not detected. The tetM and tetW genes were found in 62.2% and 13.3%, respectively. Other resistance-related genes including nim and catD were not observed in any of the isolates. Sequencing analysis of gyrA and gyrB revealed that the substitution of Thr82 to Ile in GyrA was the major amino acid change in the resistant strains (15/19). Also, substitution of Asp426 to Asn in GyrB was responsible for resistance to other moxifloxacin resistant isolates (4/19). Our data indicated notable virulence and antibiotic resistance traits amongst the isolates. Therefore, infection control strategies should be performed in order to curb the colonization and dissemination of C. difficile strains in hospital.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by Shiraz University of Medical Sciences grant no. 96-14911. The results described in this paper were part of PhD thesis of H Heidari under the supervision of Dr A Bazargani.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Berger FK, Rasheed SS, Araj GF, Mahfouz R, Rimmani HH, Karaoui WR, et al. Molecular characterization, toxin detection and resistance testing of human clinical Clostridium difficile isolates from Lebanon. Int J Med Microbiol. 2018;308:358–363. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2018.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lim SC, Androga GO, Knight DR, Moono P, Foster NF, Riley TV. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Clostridium difficile isolated from food and environmental sources in Western Australia. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2018;52:411–415. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2018.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Janoir C. Virulence factors of Clostridium difficile and their role during infection. Anaerobe. 2016;37:13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2015.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aktories K, Papatheodorou P, Schwan C. Binary Clostridium difficile toxin (CDT) - a virulence factor disturbing the cytoskeleton. Anaerobe. 2018;53:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2018.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tokimatsu I, Shigemura K, Osawa K, Kinugawa S, Kitagawa K, Nakanishi N, et al. Molecular epidemiologic study of Clostridium difficile infections in university hospitals: results of a nationwide study in Japan. J Infect Chemother. 2018;24:641–647. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2018.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stubbs S, Rupnik M, Gibert M, Brazier J, Duerden B, Popoff M. Production of actin-specific ADP-ribosyltransferase (binary toxin) by strains of Clostridium difficile. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2000;186:307–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang H, Weintraub A, Fang H, Nord CE. Antimicrobial resistance in Clostridium difficile. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2009;34:516–522. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peng Z, Jin D, Kim HB, Stratton CW, Wu B, Tang YW, et al. Update on antimicrobial resistance in Clostridium difficile: resistance mechanisms and antimicrobial susceptibility testing. J Clin Microbiol. 2017;55:1998–2008. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02250-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abuderman AA, Mateen A, Syed R, Sawsan Aloahd M. Molecular characterization of Clostridium difficile isolated from carriage and association of its pathogenicity to prevalent toxic genes. Microb Pathog. 2018;120:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2018.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang J, Zhang X, Liu X, Cai L, Feng P, Wang X, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Clostridium difficile isolates from ICU colonized patients revealed alert to ST-37 (RT 017) isolates. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2017;89:161–163. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2017.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spigaglia P, Mastrantonio P. Comparative analysis of Clostridium difficile clinical isolates belonging to different genetic lineages and time periods. J Med Microbiol. 2004;53:1129–1136. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.45682-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sedigh Ebrahim-Saraie H, Heidari H, Amanati A, BazarganiA , Alireza Taghavi S, Nikokar I, et al. A multicenter-based study on epidemiology, antibiotic susceptibility and risk factors of toxigenic Clostridium difficile in hospitalized patients in southwestern Iran. Infez Med. 2018;26:308–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jamal W, Pauline E, Rotimi V. A prospective study of community-associated Clostridium difficile infection in Kuwait: epidemiology and ribotypes. Anaerobe. 2015;35:28–32. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jamal WY, Rotimi VO. Surveillance of antibiotic resistance among hospital- and community-acquired toxigenic Clostridium difficile isolates over 5-year period in Kuwait. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0161411. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lemee L, Dhalluin A, Testelin S, Mattrat MA, Maillard K, Lemeland JF, et al. Multiplex PCR targeting tpi (triose phosphate isomerase), tcdA (toxin A), and tcdB (toxin B) genes for toxigenic culture of Clostridium difficile. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:5710–5714. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.12.5710-5714.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Terhes G, Urban E, Soki J, Hamid KA, Nagy E. Community-acquired Clostridium difficile diarrhea caused by binary toxin, toxin A, and toxin B gene-positive isolates in Hungary. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:4316–4318. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.9.4316-4318.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wayne PA. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Clinical and laboratory standards institute (CLSI) 28th informational supplement. 2018. :M100–S28. [Google Scholar]

- 18.The european committee on antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters, version 8, 2018. http://www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints/

- 19.Trinh S, Reysset G. Detection by PCR of the nim genes encoding 5-nitroimidazole resistance in Bacteroides spp. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2078–2084. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.9.2078-2084.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fry PR, Thakur S, Abley M, Gebreyes WA. Antimicrobial resistance, toxinotype, and genotypic profiling of Clostridium difficile isolates of swine origin. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:2366–2372. doi: 10.1128/JCM.06581-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spigaglia P, Barbanti F, Mastrantonio P, Brazier JS, Barbut F, Delmee M, et al. Fluoroquinolone resistance in Clostridium difficile isolates from a prospective study of C difficile infections in Europe. J Med Microbiol. 2008;57:784–789. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47738-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karlowsky JA, Adam HJ, Kosowan T, Baxter MR, Nichol KA, Laing NM, et al. PCR ribotyping and antimicrobial susceptibility testing of isolates of Clostridium difficile cultured from toxin-positive diarrheal stools of patients receiving medical care in Canadian hospitals: the Canadian Clostridium difficile Surveillance Study (CAN-DIFF) 2013-2015. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2018;91:105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2018.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Costa CL, Mano de Carvalho CB, Gonzalez RH, Gifoni MAC, Ribeiro RA, Quesada-Gomez C, et al. Molecular epidemiology of Clostridium difficile infection in a Brazilian cancer hospital. Anaerobe. 2017;48:232–236. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2017.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weber I, Riera E, Deniz C, Perez JL, Oliver A, Mena A. Molecular epidemiology and resistance profiles of Clostridium difficile in a tertiary care hospital in Spain. Int J Med Microbiol. 2013;303:128–133. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2013.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vaishnavi C, Singh M, Mahmood S, Kochhar R. Prevalence and molecular types of Clostridium difficile isolates from faecal specimens of patients in a tertiary care centre. J Med Microbiol. 2015;64:1297–1304. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rezazadeh Zarandi E, Mansouri S, Nakhaee N, Sarafzadeh F, Iranmanesh Z, Moradi M. Frequency of antibiotic associated diarrhea caused by Clostridium difficile among hospitalized patients in intensive care unit, Kerman, Iran. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2017;10:229–234. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goncalves C, Decre D, Barbut F, Burghoffer B, Petit JC. Prevalence and characterization of a binary toxin (actin-specific ADP-ribosyltransferase) from Clostridium difficile. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:1933–1939. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.5.1933-1939.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krutova M, Nyc O, Matejkova J, Allerberger F, Wilcox MH, Kuijper EJ. Molecular characterisation of Czech Clostridium difficile isolates collected in 2013-2015. Int J Med Microbiol. 2016;306:479–485. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cejas D, Rios Osorio NR, Quiros R, Sadorin R, Berger MA, Gutkind G, et al. Detection and molecular characterization of Clostridium difficile ST 1 in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Anaerobe. 2018;49:14–17. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2017.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu XS, Li WG, Zhang WZ, Wu Y, Lu JX. Molecular characterization of Clostridium difficile isolates in China from 2010 to 2015. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:845–852. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luo Y, Zhang W, Cheng JW, Xiao M, Sun GR, Guo CJ, et al. Molecular epidemiology of Clostridium difficile in two tertiary care hospitals in Shandong province, China. Infect Drug Resist. 2018;11:489–500. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S152724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peng Z, Addisu A, Alrabaa S, Sun X. Antibiotic resistance and toxin production of Clostridium difficile isolates from the hospitalized patients in a large hospital in Florida. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:2584–2591. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Androga GO, Knight DR, Lim SC, Foster NF, Riley TV. Antimicrobial resistance in large clostridial toxin-negative, binary toxin-positive Clostridium difficile ribotypes. Anaerobe. 2018;54:55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2018.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jimenez A, Araya R, Paniagua D, Camacho-Mora Z, Du T, Golding GR, et al. Molecular epidemiology and antimicrobial resistance of Clostridium difficile in a national geriatric hospital in Costa Rica. J Hosp Infect. 2018;99:475–480. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2018.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gao Q, Wu S, Huang H, Ni Y, Chen Y, Hu Y, et al. Toxin profiles, PCR ribotypes and resistance patterns of Clostridium difficile: a multicentre study in China, 2012-2013. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2016;48:736–739. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2016.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hidalgo-Villeda F, Tzoc E, Torres L, Bu E, Rodriguez C, Quesada-Gomez C. Diversity of multidrug-resistant epidemic Clostridium difficile NAP1/RT027/ST01 strains in tertiary hospitals from Honduras. Anaerobe. 2018;52:75–78. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2018.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rodriguez C, Fernandez J, Van Broeck J, Taminiau B, Avesani V, Boga JA, et al. Clostridium difficile presence in Spanish and Belgian hospitals. Microb Pathog. 2016;100:141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2016.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hampikyan H, Bingol EB, Muratoglu K, Akkaya E, Cetin O, Colak H. The prevalence of Clostridium difficile in cattle and sheep carcasses and the antibiotic susceptibility of isolates. Meat Sci. 2018;139:120–124. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2018.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goudarzi M, Goudarzi H, Alebouyeh M, Azimi Rad M, Shayegan Mehr FS, Zali MR, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Clostridium difficile clinical isolates in Iran. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2013;15:704–711. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.5189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Freeman J, Vernon J, Pilling S, Morris K, Nicholson S, Shearman S, et al. The ClosER study: results from a three-year pan-European longitudinal surveillance of antibiotic resistance among prevalent Clostridium difficile ribotypes, 2011-2014. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018;24:724–731. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2017.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Freeman J, Vernon J, Morris K, Nicholson S, Todhunter S, Longshaw C, et al. Pan-European longitudinal surveillance of antibiotic resistance among prevalent Clostridium difficile ribotypes. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21:248 e249–248 e216. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2014.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kuwata Y, Tanimoto S, Sawabe E, Shima M, Takahashi Y, Ushizawa H, et al. Molecular epidemiology and antimicrobial susceptibility of Clostridium difficile isolated from a university teaching hospital in Japan. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2015;34:763–772. doi: 10.1007/s10096-014-2290-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cheng JW, Yang QW, Xiao M, Yu SY, Zhou ML, Kudinha T, et al. High in vitro activity of fidaxomicin against Clostridium difficile isolates from a university teaching hospital in China. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2018;51:411–416. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2017.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]