Abstract

Background

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is currently a pandemic affecting over 200 countries. Many cities have established designated fever clinics to triage suspected COVID-19 patients from other patients with similar symptoms. However, given the limited availability of the nucleic acid test as well as long waiting time for both the test and radiographic examination, the quarantine or therapeutic decisions for a large number of mixed patients were often not made in time. We aimed to identify simple and quickly available laboratory biomarkers to facilitate effective triage at the fever clinics for sorting suspected COVID-19 patients from those with COVID-19-like symptoms.

Methods

We collected clinical, etiological, and laboratory data of 989 patients who visited the Fever Clinic at Wuhan Union Hospital, Wuhan, China, from Jan 31 to Feb 21. Based on polymerase chain reaction (PCR) nucleic acid testing for SARS-CoV-2 infection, they were divided into two groups: SARS-CoV-2-positive patients as cases and SARS-CoV-2-negative patients as controls. We compared the clinical features and laboratory findings of the two groups, and analyzed the diagnostic performance of several laboratory parameters in predicting SARS-CoV-2 infection and made relevant comparisons to the China diagnosis guideline of having a normal or decreased number of leukocytes (≤9·5 109/L) or lymphopenia (<1·1 109/L).

Findings

Normal or decreased number of leukocytes (≤9·5 109/L), lymphopenia (<1·1 109/L), eosinopenia (<0·02 109/L), and elevated hs-CRP (≥4 mg/L) were presented in 95·0%, 52·2%, 74·7% and 86·7% of COVID-19 patients, much higher than 87·2%, 28·8%, 31·3% and 45·2% of the controls, respectively. The eosinopenia produced a sensitivity of 74·7% and specificity of 68·7% for separating the two groups with the area under the curve (AUC) of 0·717. The combination of eosinopenia and elevated hs-CRP yielded a sensitivity of 67·9% and specificity of 78·2% (AUC=0·730). The addition of eosinopenia alone or the combination of eosinopenia and elevated hs-CRP into the guideline-recommended diagnostic parameters for COVID-19 improved the predictive capacity with higher than zero of both net reclassification improvement (NRI) and integrated discrimination improvement (IDI).

Interpretation

The combination of eosinopenia and elevated hs-CRP can effectively triage suspected COVID-19 patients from other patients attending the fever clinic with COVID-19-like initial symptoms. This finding would be particularly useful for designing triage strategies in an epidemic region having a large number of patients with COVID-19 and other respiratory diseases while limited medical resources for nucleic acid tests and radiographic examination.

Keywords: Eosinopenia, Elevated hs-crp, Covid-19, Triage

Research in context.

Evidence before this studyAs of April 3, 2020, the outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) has led to 972,303 confirmed cases with 50,322 deaths globally. In Wuhan, a large number of mixed patients of true or suspected COVID-19 cases and those with other pneumonia or respiratory infections swarmed into designated fever clinics. This brought tremendous pressure on patient triage at fever clinics. However, most of published COVID-19 papers focused on clinical characteristics of hospitalized patients but not COVID-19 outpatients. We searched PubMed for studies related to the biomarkers for effective triage of COVID-19 in clinics up to April 3, 2020. The search terms included “triage”, “prediction”, “biomarker”, and “COVID-19″, and yield no relevant papers.

Added value of this studyTo the best of our knowledge, this is the first retrospective analysis focused on how to improve triage process during COVID-19 outbreak at fever clinics. We compared laboratory findings between laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2-positive patients and SARS-CoV-2-negative patients, both of which presented similar fever and respiratory symptoms. Differentiating these two types of patients was a core question to be solved during triage at fever clinics. Our study revealed that eosinopenia and elevated high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) level were observed in the majority of SARS-CoV-2-positive patients, and the combination of eosinopenia and elevated hs-CRP was capable of predicting true COVID-19 patients (72.8% positive prediction) more efficiently than the combination of “normal or decreased number of leukocytes” and/or “lymphopenia” (48.4% positive prediction), two diagnostic parameters recommended by the Guideline of the China National Health Committee for COVID-19 diagnosis (6th edition).

Implications of all the available evidenceEosinopenia along with increased hs-CRP can be used to rapidly and effectively triage suspected cases from mixed patients with similar COVID-19-related symptoms at fever clinics. These patients should be prioritized for computerized tomography (CT) diagnostic examination and COVID-19 nucleic acid polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing when resources are limited. Our finding may provide useful information for designing proper triage strategies in regions, which have begun to struggle with COVID-19 outbreak or might have similarly intense COVID-19 local outbreak in the future.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

1. Introduction

As of April 3, 2020, laboratory-confirmed severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection across China has reached over 80,000 cases [1]. The WHO named this coronavirus disease as COVID-19 and declared it as a public health emergency of international concern [2]. COVID-19 has now affected over 200 countries and territories [3], [4], [5], and a surge in cases (972,303 confirmed cases with 50,322 deaths globally) has been noted in multiple countries outside of China, including the United States, Italy, Spain, Germany, France, Iran, the United Kingdom, Japan, and South Korea [3,6]. Such an urgent situation underscores the importance of effectively identifying infected patients for timely treatment in relevant epidemic regions.

A key to slow the spread towards outbreak containment is rapid diagnosis and isolation of cases [7]. This relies on effective triage protocols identifying suspected patients for isolation or further diagnostic examination towards timely treatment [8,9]. By referring to previous experience of combatting SARS-CoV in 2003 in China, designated fever clinics were quickly established across epidemic regions to triage suspected patients. COVID-19-like initial symptoms include fever and respiratory symptoms (such as dry cough and shortness of breath) [10]. These symptoms are however not specific, and readily confused with other non-bacterial community-acquired pneumonia or common upper respiratory infection. Thus, a critical task of triage at the fever clinic was how to accurately and effectively sort suspected COVID-19 patients from those of other pneumonia or respiratory infection who presented with COVID-19-like symptoms.

This triage was particularly challenging because immediately after the COVID-19 outbreak, an overwhelmingly large number of mixed patients with fever or respiratory symptoms flooded in, resulting in long waiting time for computerized tomography (CT) examination and etiological polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests. This significantly delayed diagnosis and subsequent quarantine or therapeutic decisions. Due to these reasons, many true COVID-19 patients were left un-diagnosed at fever clinics causing cross infection, or were self-isolated at home, which was however often ineffective and could lead to family cluster infections and poor prognosis because of delayed treatment. Therefore, it is highly desired to develop more effective ways of optimizing the triage process at fever clinics to sort suspected COVID-19 patients out of patients with similar symptoms. Those suspected COVID-19 patients would be prioritized for diagnostic CT examination and etiological PCR tests. Thus, we set to identify simple and quickly available laboratory parameters as biomarkers for precise and effective triage.

2. Methods

2.1. Patients

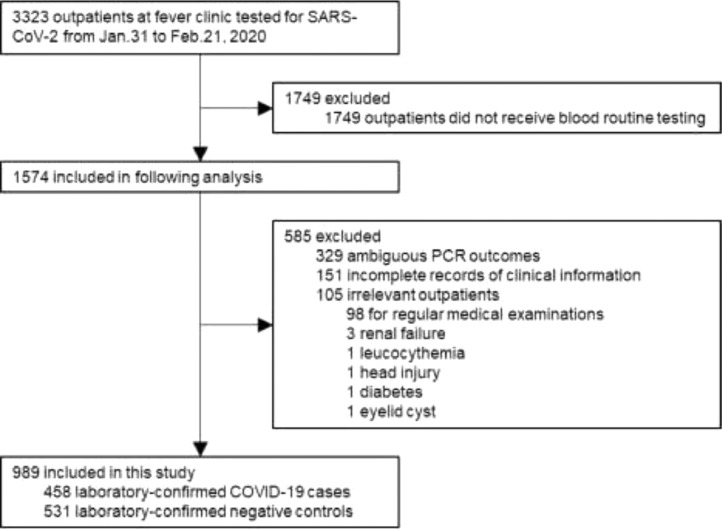

Data of this retrospective case-control study were consecutively collected from 3323 patients who made first medical visit at the Fever Clinic of Wuhan Union Hospital from Jan 31 to Feb 21, 2020, prior to any antiviral and anti-bacterial treatments that they might receive later on. The majority of the patients presented fever and/or respiratory symptoms at the fever clinic. We excluded patients without blood routine examinations (n = 1749) mainly because these patients (1) had already received blood routine examination in community clinics and their blood testing results were not obtainable, (2) were transferred to designated hospitals for isolation and treatment, or (3) made their own decisions to refuse further routine blood tests or go to other hospitals for further testing and treatment. We also excluded patients who already had CT examination and were considered as suspected COVID-19 cases (n = 151), those with unknown status of SARS-CoV-2 infection (n = 329), and those with irrelevant symptoms or conditions (n = 105). Finally, a total of 989 patients were included for the analyses (Fig. 1). All patients’ throat swab specimens were subject to nucleic acid testing for SARS-CoV-2. Among them, 458 patients were tested positive and considered as COVID-19 cases and 531 were tested negative and considered as controls. Two researchers independently extracted and reviewed the data. This study was approved by the Wuhan Union Hospital Ethics Committee.

Fig. 1.

Study flow. COVID-19, coronavirus disease; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

2.2. Procedures

Etiological examination, blood routine analysis, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) quantification were performed in clinical laboratory of Wuhan Union Hospital. Blood biomarker tests were carried out by a SYSMEX automatic blood analyzer (Sysmex Corporation, Kobe, Japan). The laboratory-confirmation of SARS-CoV-2 infection was carried out by real time reverse-transcription PCR (RT-PCR) through amplifying ORF1ab gene and N gene of SARS-CoV-2 (BioGerm, Shanghai, China) from throat swab specimens of all patients. The sequences for amplifying ORF1ab gene and detecting products were: forward primer 5′-CCCTGTGGGTTTTACACTTAA-3′, reverse primer 5′-ACGATTGTGCATCAGCTGA-3′, fluorescence probe 5′-FAM-CCGTCTGCGGTATGTGGAAAGGTTATGC-BHQ1-3′; the sequences for amplifying N gene and detecting products were: forward primer 5′-GGGGAACTTCTCCTGCTAGAAT-3′, reverse primer 5′-CAGACATTTTGCTCTCAAGCTG-3′, fluorescence probe 5′-FAM-TTGCTGCTGCTTGACAGATT-TAMRA-3′. A cycle threshold value < 35 (or > 35 but less than 38 for two times) was defined as positive.

2.3. Definitions

The WHO interim guidance for COVID-1911 defines suspected cases that should meet two criteria: (1) clinical features: respiratory-infection symptoms that cannot be fully explained by other etiology; and (2) epidemiological features (affected geographic regions travel history or close contact with a confirmed or probable case). In the WHO interim guidance, the laboratory evidence was not required to define a suspected case. In addition to WHO guideline, different countries can have their own guidelines. In China, the Guidelines of the National Health Commission of China for COVID-19 (6th edition) [12] was followed during this study. According to it, suspected COVID-19 cases would have the following features: (1) recent travel history to Wuhan City or Hubei Province or close contact with a confirmed or probable case; (2) fever and/ or respiratory symptoms; (3) laboratory findings of normal or decreased number of leukocytes and/ or lymphopenia; (4) radiographic evidence showing pneumonia. The suspected cases were defined if they met the following criteria: (1) plus any two of (2)(3)(4), or three of (2)(3)(4) at the same time. For simplicity, the two parameters (normal or decreased number of leukocytes and/or lymphopenia) described in “(3)” were referred to as one term “Guideline” for the following analyses.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Biomarkers from blood routine examination were dichotomized according to normal reference range used in clinics. Characteristics of laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2-positive and SARS-CoV-2-negative patients were compared using Mann-Whitney U tests or chi-square tests where appropriate. Univariate logistic models were established to examine risk factors for COVID-19. Those showing significant associations were further included in the multivariable logistic analysis.

Significant biomarkers both in the aforementioned univariate and multivariable logistic analyses were then used to construct the prediction models. The diagnostic performance of each prediction model was evaluated using sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), Youden index (YI) [13], and consistency rate (CR). The improvement in discrimination was assessed by comparing the area under the curve (AUC) of receiver operating characteristic (ROC) between the “Guideline” and the model plus the biomarkers identified from the above analyses [14]. Net reclassification improvement (NRI, the improvement in classification probabilities) and integrated discrimination improvement (IDI, the improvement in discrimination) statistics were also utilized as supplementary approaches to assess the incremental improvement in prediction over the existing “Guideline” [15,16]. In addition, Akaike information criteria (AIC) was used to assess the goodness of fit of all models, with lower AICs indicating better model fit.

Among 531 patients who were tested negative for the SARS-CoV-2 infection, 95 had two or more nucleic acid tests that were all negative. Thus, we used these 95 patients as the controls in a sensitivity analysis given that they were most unlikely true COVID-19 patients. Since we did not have a validation cohort and our selected model might be subject to overfitting, a 10-fold cross-validation method (9 training datasets and 1 validation dataset) was utilized to evaluate the goodness-of-fit of the model identified from the above analyses [17]. To evaluate the influence of missing values for the hs-CRP, a sensitivity analysis of excluding those with missing data was performed. A 2-tailed p value <0·05 was considered as statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using Stata version 15·0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA).

2.5. Role of funding

NSFC and MSTIP had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

3. Results

Table 1 showed the basic demographic factors and laboratory parameters in the two groups. The median age (IQR) was 59·5 years (48·0–68·0 years) in patients with COVID-19 and 50·0 years (37·0–62·0 years) in the controls. As for laboratory findings, COVID-19 patients had significantly lower levels of leukocytes (5·2 109/L), neutrophils (3·5 109/L), lymphocytes (1·1 109/L), eosinophils (0·01 109/L), and platelets (178·0 109/L), but higher levels of hs-CRP (27·4 mg/L) (all p value <0·05), while similar levels of monocytes (0·37 109/L), red blood cell counts (4·7 1012/L), and hemoglobin (140·0 g/L) (all p value >0·05), compared to the controls. When dichotomized into binary variables, eosinopenia (<0·02 109/L) and elevated hs-CRP (≥4 mg/L) were present in 74·7% and 86·7% of COVID-19 patients, much higher than 31·3% and 45·2% of the controls, respectively. Meanwhile, 97·8% of the patients with COVID-19 and 89·8% of the controls had normal or decreased number of leukocytes and/or lymphopenia, two recommended parameters (referred to as “Guideline” in this study) as a criterion for defining suspected COVID-19 case in Wuhan throughout our study (see “Definition” section in Methods). The univariate analysis revealed a similar pattern. In the multivariable analysis, age, normal or decreased number of leukocytes, decreased neutrophils, eosinopenia, elevated hs-CRP, and the “Guideline” recommended parameters remained significantly associated with COVID-19.

Table 1.

Comparison of clinical features and blood biomarkers between patients with and without COVID-19.

| Variables | Controls (n = 531) | COVID cases (n = 458) | Univariate model | Multivariate model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI)* | OR (95% CI)* | |||

| Clinical features | ||||

| Age, years | 50·0 (37·0–62·0) | 59·5 (48·0–68·0) | 1·03 (1·03–1·04) | 1·02 (1·00–1·03) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 235 (44·3%) | 205 (44·8%) | 1·00 | – |

| Female | 296 (55·7%) | 253 (55·2%) | 0·98 (0·76–1·26) | – |

| Blood biomarkers | ||||

| Leukocyte (109/L; Ref: 3·5–9·5) | 6·0 (4·8–7·9) | 5·2 (4·1–6·7) | ||

| Normal or decreased (≤9·5)† | 463 (87·2%) | 435 (95·0%) | 2·78 (1·70–4·54) | 3·49 (2·00–6·08) |

| Neutrophil (109/L; Ref: 1·8–6·3) | 4·0 (2·9–5·5) | 3·5 (2·6–4·9) | ||

| Decreased (<1·8) | 12 (2·3%) | 32 (7·0%) | 3·25 (1·65–6·39) | 2·35 (1·06–5·20) |

| Lymphocyte (109/L; Ref: 1·1–3·2) | 1·5 (1·0–1·9) | 1·1 (0·8–1·4) | ||

| Decreased (<1·1)† | 153 (28·8%) | 239 (52·2%) | 2·70 (2·07–3·51) | 0·94 (0·68–1·31) |

| Monocyte (109/L; Ref: 0·1–0·6) | 0·39 (0·30–0·52) | 0·37 (0·28–0·51) | ||

| Increased (>0·6) | 74 (13·9%) | 61 (13·3%) | 0·95 (0·66–1·37) | – |

| Eosinophil (109/L; Ref: 0·02–0·52) | 0·04 (0·01–0·09) | 0·01 (0·0–0·02) | ||

| Decreased (<0·02) | 166 (31·3%) | 342 (74·7%) | 6·48 (4·90–8·57) | 3·51 (2·55–4·82) |

| Red blood cell count (1012/L; male Ref: 4·3–5·8; female Ref: 3·8–5·1) | 4·7 (4·3–5·1) | 4·7 (4·4–5·1) | ||

| Increased (>5·8 for male and >5·1 for female) | 29 (5·5%) | 39 (8·5%) | 1·61 (0·98–2·65) | – |

| Hemoglobin (g/L; male Ref: 130 −175; female Ref: 115 −150) | 140·0 (128·0–150·0) | 140·0 (131·0–150·0) | ||

| Increased (>175 for male and >150 for female) | 15 (2·8%) | 30 (6·6%) | 2·41 (1·28–4·54) | 2·16 (1·00–4·66) |

| Platelet (109/L; Ref: 125–350) | 224·0 (183·0–285·0) | 178·0 (144·0–220·0) | ||

| Decreased (<125) | 23 (4·3%) | 64 (14·0%) | 3·59 (2·19–5·88) | 1·55 (0·89–2·72) |

| hs-CRP (mg/L; Ref:<4·0) | 3·1 (0·5–14·8) | 27·4 (8·9–66·8) | ||

| Increased (≥4·0) | 240 (45·2%) | 397 (86·7%) | 7·89 (5·74–10·86) | 4·75 (3·28–6·88) |

| Guideline parameters (Normal or decreased leukocyte and/or decreased lymphocyte)† | 477 (89·8%) | 448 (97·8%) | 5·07 (2·55–10·08) | 4·64 (2·20–9·77) |

Data are presented as n (%) and median (IQR).

CI, confidence interval; COVID-19, coronavirus disease; hs-CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; OR, odds ratio; Ref., normal reference range.

The OR (95% CI) was calculated as the comparison of the abnormal biomarker group compared to the normal range group for the odds of having the COVID-19 disease.

Normal or decreased leukocytes, and lymphopenia were not included in the calculation of OR (95% CI) for the guideline in the multivariate model, and vice versa.

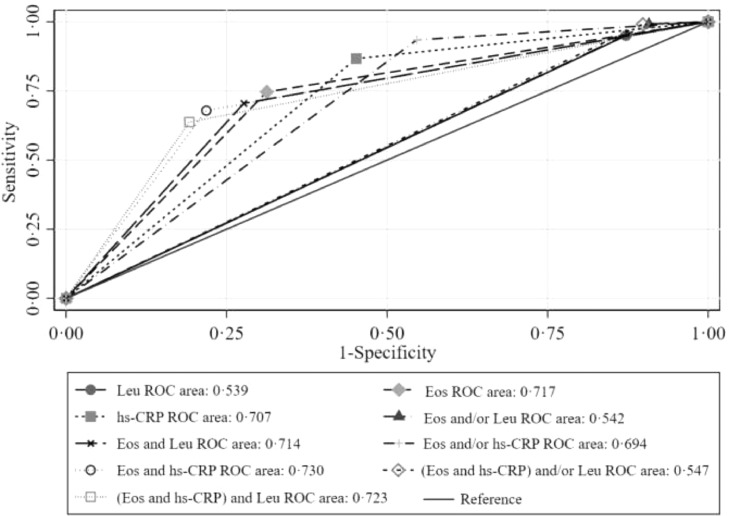

We further evaluated the predictive capacity of those significant blood biomarkers (eosinopenia, elevated hs-CRP, and normal/ decreased leukocyte counts) both in the aforementioned univariate and multivariable logistic analyses. Since less than 10% of the participants had decreased neutrophils, this parameter was not included in the diagnostic performance analyses. Among the 3 remaining biomarkers, we found that the eosinopenia produced the highest specificity (68·7%), PPV (67·3%), YI (43·4%), CR (71·5%), and AUC (0·717). Then, the eosinopenia was further singly or doubly combined with the other 2 biomarkers. We found that the combination of eosinopenia and elevated hs-CRP yielded the highest specificity (78·2%), PPV (72·8%), YI (46·1%), and CR (73·4%), with an improved model fit (AIC values=1149·5). No further improvement was observed when the parameter of “normal/decreased leukocytes” was added into the eosinopenia and elevated hs-CRP combination (Table 2). Consistently, the highest AUC was found for the combination of eosinopenia and elevated hs-CRP (AUC = 0·730), followed by the combination of eosinopenia and elevated hs-CRP plus “normal/decreased leukocytes” (AUC = 0·723), and then by eosinopenia alone (AUC = 0·717) (Fig. 2). These results remained largely unchanged in the sensitivity analysis when only using 95 patients who had two or more consecutive negative nucleic acid testing results as the controls (table S1 and 2, and figure S1). The 10-fold cross-validation method also produced the same results (table S3). Similar results were produced in the10-fold cross-validation method (table S3), as well as in the sensitivity analysis of excluding those with missing data (table S4).

Table 2.

Diagnostic performance of single and combined blood biomarkers on differentiating patients with COVID-19 (n = 458) from controls patients (n = 531).

| Prediction models | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | YI (%) | CR (%) | AIC | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leu (≤9·5) | 95·0 | 12·8 | 48·4 | 74·7 | 7·8 | 50·9 | 1350·9 | 0·539 (0·522–0·556) |

| Eos (<0·02) | 74·7 | 68·7 | 67·3 | 75·9 | 43·4 | 71·5 | 1177·4 | 0·717 (0·689–0·745) |

| hs-CRP (≥4·0) | 86·7 | 54·8 | 62·3 | 82·7 | 41·5 | 69·6 | 1172·6 | 0·707 (0·681–0·734) |

| Eos (<0·02) and/or Leu (≤9·5) | 99·1 | 9·2 | 48·5 | 92·5 | 8·3 | 50·9 | 1329·1 | 0·542 (0·529–0·555) |

| Eos (<0·02) and Leu (≤9·5) | 70·5 | 72·3 | 68·7 | 74·0 | 42·8 | 71·5 | 1183·0 | 0·714 (0·686–0·742) |

| Eos (<0·02) and/or hs-CRP (≥4·0) | 93·5 | 45·4 | 59·6 | 88·9 | 38·9 | 67·6 | 1161·3 | 0·694 (0·670–0·718) |

| Eos (<0·02) and hs-CRP (≥4·0) | 67·9 | 78·2 | 72·8 | 73·8 | 46·1 | 73·4 | 1149·5 | 0·730 (0·703–0·758) |

| (Eos (<0·02) and hs-CRP [≥4·0]) and/or Leu (≤9·5) | 99·1 | 10·2 | 48·8 | 93·1 | 9·3 | 51·4 | 1323·2 | 0·547 (0·533–0·560) |

| (Eos (<0·02) and hs-CRP [≥4·0]) and Leu (≤9·5) | 63·8 | 80·8 | 74·1 | 72·1 | 44·6 | 72·9 | 1159·1 | 0·723 (0·695–0·750) |

The unit is mg/L for hs-CRP, and 109/L for Leu, Lym, and Eos.

AIC, Akaike information criteria; AUC, area under the curve; COVID-19, coronavirus disease; CR, consistency rate; Eos: eosinopenia; hs-CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein increased; Leu: normal or decreased number of leukocytes; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value; YI, Youden index.

Fig. 2.

ROC curves of single and combined blood biomarkers on differentiating patients with COVID-19 (n = 458) from the controls (n = 531). COVID-19, coronavirus disease; Eos: eosinopenia; hs-CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein increased; Leu: normal or decreased number of leukocytes; ROC, receiver operating characteristic.

Table 3 showed that the “Guideline” parameters produced the highest sensitivity (97·8%) but the lowest specificity (10·2%) with an AUC of 0·540. Higher specificity (71·0% and 78·2%), PPV (68·5% and 72·8%), YI (44·1% and 46·1%), and CR (72·0% and 73·4%) were found for the combination of the “Guideline” plus eosinopenia alone, and for the combination of “Guideline” plus both eosinopenia and elevated hs-CRP, respectively, with improved model fits (AIC values=1161·4 and 1133·0, respectively). Notably, a higher AUC was also found for the “Guideline” plus eosinopenia alone (AUC=0·731), and the “Guideline” plus both eosinopenia and elevated hs-CRP (AUC=0·745). Compared to the “Guideline” parameters, the model added with eosinopenia alone or the combination of eosinopenia and elevated hs-CRP showed a more significant improvement in the prediction capacity with higher than zero of both NRI and IDI (Table 3). Consistently, these results remain mostly similar in the sensitivity analysis when only using 95 patients who had two or more consecutive negative nucleic acid testing results as the controls (table S5).

Table 3.

Comparison of the diagnostic performance between the Guideline parameters and the Guideline parameters plus Eos/ (Eos and hs-CRP) (n = 989).

| Prediction models | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | YI (%) | CR (%) | AIC | AUC | NRI | IDI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leu (≤9·5) and/or Lym (<1·1) (referred to as “Guideline”) | 97·8 | 10·2 | 48·4 | 84·4 | 8·0 | 50·8 | 1340·9 | 0·540 (0·525–0·554) | – | – |

| Guideline + Eos (<0·02) | 73·1 | 71·0 | 68·5 | 75·4 | 44·1 | 72·0 | 1161·4 | 0·731 (0·703–0·759) | 0·868 | 0·175 |

| Guideline + (Eos [<0·02] and hs-CRP [≥4·0]) | 67·9 | 78·2 | 72·8 | 73·8 | 46·1 | 73·4 | 1133·0 | 0·745 (0·718–0·772) | 0·921 | 0·202 |

The unit is mg/L for hsCRP, and 109/L for Leu, Lym, and Eos.

AIC, Akaike information criteria; AUC, area under the curve; CR, consistency rate; Eos: eosinopenia; hs-CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein increased; IDI, integrated discrimination improvement; Leu: normal or decreased number of leukocytes; Lym: lymphopenia; NRI, net reclassification improvement; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value; YI, Youden index.

4. Discussion

Clinics play important roles in response to COVID-19 outbreak, such as setting up protocols for triaging and isolating suspected COVID-19 patients so that they do not infect others. Triage processes were evolvingly optimized as our understanding of COVID-19 progress. In light of this rationale, we performed this analysis. Our case-control study revealed that the combination of eosinopenia and elevated hs-CRP as a potential effective predictor of COVID-19 patients from other patients with similar symptoms. The combination of eosinopenia and elevated hs-CRP produced a sensitivity of 67·9% and specificity of 78·2% with an AUC of 0·730. More importantly, the PPV was 72·8%, indicating that 72·8% of those classified as positive in our model are true COVID-19 patients. Even if hs-CRP was not included, eosinopenia alone could also produce a sensitivity of 74·7%, a specificity of 68·7%, and a PPV of 67·3%.

An early clinical study in Wuhan reported that 86·3% of patients (63 of 73 patients) with COVID-19 had elevated hs-CRP levels [18]. We also observed a similar proportion in our study (86·7%). Notably, a previous study demonstrated that increased hs-CRP also appeared in asymptomatic patients, suggesting a potential significance of hs-CRP in latent SARS-CoV-2 infection [19]. The increased hs-CRP levels were likely due to COVID-19 related acute inflammatory pathogenesis during which multiple cytokines were released and their amount was associated with disease severity [20].

Notably, in addition to hs-CRP, eosinopenia appeared in the majority of patients with COVID-19. Eosinopenia was reportedly observed in other diseases, such as typhoid fever during which possible viral attach in bone marrow reduced the production of eosinophils [21]. In our cases, although the detailed mechanisms were unclear, the possibilities included viral attacking bone marrow, blocking eosinophils’ entrance into peripheral circulation, or infiltration into certain organs (such as lungs) [22] for which further analysis of tissue from autopsy [23] or bone marrow aspiration might provide some clues.

Possibly due to unclear functional roles of eosinophils in infectious diseases, changes in eosinophils in peripheral blood did not attract attention in the early studies about COVID-19 [10,18,20,24], and in previous clinical reports on MERS-CoV [25]. However, we noted that eosinopenia was in the laboratory findings of all the five patients infected by an asymptomatic COVID-19 carrier in a recently published case report [26]. Moreover, our literature search found a paper reporting that nearly 90% of 2003 SARS-CoV patients had eosinopenia in 2003 [27]. They reported that eosinopenia could be observed at admission, persisted throughout the clinical course, and was resolved after improvement of symptoms, or kept at a low level when illness was worsened. In our study, eosinopenia was found at patients’ first medical visit, suggesting that it might be an early event of COVID-19 infection, likely prior to emergence of characteristic radiological findings. But whether or not the dynamic changes of eosinopenia was similar to SARS-CoV during disease course of COVID-19 awaits further study. In addition, none of the SARS-CoV-2-positive patients in our study presented increased number of eosinophils, suggesting that eosinophil counts do not generally increase at the early stage of COVID-19.

Although eosinopenia's underlying mechanisms were unknown, eosinopenia's reference value for triage and diagnosis can be fully utilized. Eosinopenia as a parameter in routine blood tests in conjunction with elevated hs-CRP could be used to facilitate rapid triage and identification of highly-suspected cases from mixed patients presenting with fever and respiratory symptoms in fever clinics(figure S2). These identified suspected patients could (1) receive the priority for radio-diagnosis and laboratory-definitive diagnosis, (2) be isolated in designated wards without any delay to avoid potential virus spreading, (3) and receive empirical antiviral treatment (as of now no consensus over usage of antiviral agents) to prevent illness aggravation.

According to the definition for suspected cases by the Guideline of the National Health Commission of China for COVID-19 (6th edition, see Methods for details) [12], at fever clinics in Wuhan, the majority of patients met the first two criteria of epidemiological exposure and clinical symptoms. From our analysis, we showed that in case CT or etiological PCR testing was not available, the third criterion alone (“normal or decreased leukocytes” and/or “lymphopenia”) was not quite effective in triaging and recognizing suspected COVID-19 cases from patients with fever and other respiratory symptoms (figure S2). In the analysis, the specificity of including those two biomarkers was only 10·2% and the PPV was low, only 48·4%, meaning that more than half of patients identified using this guideline were not true COVID-19 patients. This may be because normal or decreased leukocytes and lymphopenia are not COVID-19 specific and can also be seen in other community-acquired viral pneumonia [28].

The WHO interim guideline is followed worldwide, including developed or undeveloped countries [11]. It defines suspected patients at triage based on epidemiological history and clinical symptoms. Our finding of eosinopenia and increased hs-CRP in COVID-19 patients may be a useful supplement to the triage strategy recommended by current WHO interim guideline [11], as eosinophil counts and hs-CRP levels could be conveniently measured by technically simple routine blood tests even in small community clinics in resource-limited regions, which is particularly critical given that COVID-19 has been affecting more than 200 countries and territories [3], such as countries in Middle-east and Africa [29].

This study has several limitations. First, the finding was obtained from the retrospective study, and the sample size in our study was not large and further validation of our findings in a larger prospective cohort is needed. Second, potential selection biases exist due to the hospital-based case-control study design. Third, nucleic acid test could sometimes yield false negative results mainly due to an insufficient viral load below the detection limit in collected nasopharyngeal swabs and the possible degradation of viral nuclei acids during sample collection, transportation, and storage. However, the findings were generally robust in our sensitivity analysis of using control patients who had twice or more nucleic acid negative testing results.

In summary, the combination of eosinopenia and increased hs-CRP may facilitate accurate and effective triage of suspected COVID-19 patients from the aforementioned patients with COVID-19-like pneumonia or respiratory infection. Thus, this optimized triage could speed up diagnosis and treatment for COVID-19 patients under current urgent situation. Our findings may provide useful information for regions that will be or are now beginning to struggle with the outbreak to better design triage protocols preparing for potential COVID-19 local outbreaks.

Author contributions

Dr Q. Li, X. Ding, Prof. G. Xia, and Dr H. Chen contributed equally to this work. All corresponding authors had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Z. Wang, L. Wang, A. Pan, G. Xia.

Extraction and review of data: Q. Li, X. Ding.

Analysis and interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: Z. Wang, A. Pan, L. Wang, Q. Li, X. Ding, H. Chen.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Z. Geng, F. Chen. G. Xia

Supervision: Z. Wang, L. Wang, A. Pan.

Declaration of Competing Interest

All authors declare no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC; project number: 81974382), the Major Scientific and Technological Innovation Projects of Hubei Province (MSTIP; project number 2018ACA136) and the COVID-19 Program of Huazhong University of Science and Technology (project number 2020kfyXGYJ099).

Footnotes

Funding This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) and the Major Scientific and Technological Innovation Projects of Hubei Province (MSTIP).

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100375.

Contributor Information

An Pan, Email: panan@hust.edu.cn.

Lin Wang, Email: lin_wang@hust.edu.cn.

Zheng Wang, Email: zhengwang@hust.edu.cn.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.National Health Commission of China. [The latest situation of the COVID-19 epidemic (up to Apr 3)]. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/yqtb/202004/185a308e4c66 426190da0c4f2f9ab026.shtml. Accessed Apr 4, 2020.

- 2.World Health Organization. Rolling updates on coronavirus disease (COVID-19) (Updated 18April 2020). https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/events-as-they-happen. Accessed Apr 21, 2020.

- 3.World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) situation report – 74. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200403-sitrep-74-covid-19-mp.pdf?sfvrsn=4e043d03_10. Accessed Apr 4, 2020.

- 4.Callaway E. Time to use the p-word? Coronavirus enters dangerous new phase. Nature. 2020 doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-00551-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen J., Kupferschmidt K. The coronavirus seems unstoppable. What should the world do now. Science. 2020 doi: 10.1126/science.abb4604. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Day M. COVID-19: surge in cases in Italy and South Korea makes pandemic look more likely. BMJ. 2020;368:m751. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adalja A.A., Toner E., Inglesby T.V. Priorities for the US health community responding to COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;323(14):1343–1344. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pagel C., Utley M., Ray S. Covid-19: how to triage effectively in a pandemic. BMJ. 2020 https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2020/03/09/covid-19-triage-in-a-pandemic-is-even-thornier-than-you-might-think/ [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang J., Zhou L., Yang Y. Therapeutic and triage strategies for 2019 novel coronavirus disease in fever clinics. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(3):e11–e12. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30071-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.W-j Guan, Z-y Ni, Hu Y. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization. Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when novel coronavirus (nCoV) infection is suspected. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance. Accessed Mar 5, 2020.

- 12.National Health Commission of the Peoples's Republic of China. Clinical diagnosis and treatment guidance of 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) caused pneumonia (6th edition). http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/zhengcwj/202002/8334a83 26dd94d329df351d7da8aefc2.shtml. Accessed Feb 19, 2020.

- 13.Fluss R., Faraggi D., Reiser B. Estimation of the Youden Index and its associated cutoff point. Biom J. 2005;47(4):458–472. doi: 10.1002/bimj.200410135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeLong E.R., DeLong D.M., Clarke-Pearson D.L. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988;44(3):837–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pencina M.J., D'Agostino R.B., Sr., D'Agostino R.B., Jr., Vasan R.S. Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: from area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond. Stat Med. 2008;27(2):157–172. doi: 10.1002/sim.2929. discussion 207-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pencina M.J., D'Agostino R.B., Sr., Steyerberg E.W. Extensions of net reclassification improvement calculations to measure usefulness of new biomarkers. Stat Med. 2011;30(1):11–21. doi: 10.1002/sim.4085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Linden, Ariel (2017). kfoldclass: stata module for generating classification statistics for k-fold cross-validation of binary outcomes. http://ideas.repec.org/c/boc/bocode/s458127.html

- 18.Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lei S., Jiang F., Su W. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients undergoing surgeries during the incubation period of COVID-19 infection. E Clin Med. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khosla S.N., Anand A., Singh U., Khosla A. Haematological profile in typhoid fever. Trop Doct. 1995;25(4):156–158. doi: 10.1177/004947559502500404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bass D.A., Gonwa T.A., Szejda P., Cousart M.S., DeChatelet L.R., McCall C.E. Eosinopenia of acute infection: production of eosinopenia by chemotactic factors of acute inflammation. J Clin Invest. 1980;65(6):1265–1271. doi: 10.1172/JCI109789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu Z., Shi L., Wang Y. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(4):420–422. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30076-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zumla A., Hui D.S., Perlman S. Middle east respiratory syndrome. Lancet. 2015;386(9997):995–1007. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60454-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bai Y., Yao L., Wei T. Presumed asymptomatic carrier transmission of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;323(14):1406–1407. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yao X., Zeng Y., Tong Y., Tang X., Yin Z. Determination and analysis of blood eosinophil in 200 severe acute respiratory syndrome patients. Lab Med. 2004;5(19):444–445. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruuskanen O., Lahti E., Jennings L.C., Murdoch D.R. Viral pneumonia. Lancet. 2011;377(9773):1264–1275. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61459-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Makoni M. Africa prepares for coronavirus. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):483. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30355-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.