Abstract

Objective:

Somatization and functional somatic symptoms reflect conditions in which physical symptoms are not sufficiently explained by medical conditions. Literature suggests that these somatic symptoms may be related to illness exposure in the family. Children with a parent or sibling with a chronic illness may be particularly vulnerable to developing somatic symptoms. This study provides a systematic review of the literature on somatic symptoms in children with a chronically ill family member.

Methods:

A systematic review (PROSPERO registry ID:CRD42018092344) was conducted using six databases (PubMed, EMBASE, PsychINFO, Scopus, CINAHL, and Cochrane) from articles published prior to April 5, 2018. All authors evaluated articles by title and abstract, and then by full-text review. Relevant data were extracted by the first author and reviewed by remaining authors.

Results:

Twenty-seven unique studies met criteria. Seventeen examined somatic symptoms in children with a chronically ill parent and seven evaluated somatic symptoms in children with a chronically ill sibling. Three studies examined somatic symptoms in children with an unspecified ill relative. The strongest relationship between child somatization and familial illness was found with children with a chronically ill parent (13 out of 17 studies). Evidence for somatic symptoms in children with an ill sibling was mixed (4 out of 7 studies found a positive association).

Conclusions:

The literature on somatic symptoms in children suggest parental illness is related to increased somatic symptoms in children. Research examining the effects of having a sibling with an illness on somatic symptoms is mixed. Several areas of future research are outlined to further clarify the relationship between familial chronic illness and somatic symptoms.

Keywords: somatic symptoms, parental illness, child heath

Introduction

Physical symptoms are not always adequately explained by a medical or organic condition and several labels have been used to refer to these symptoms, including somatization, persistent somatic symptoms and functional somatic symptoms (1). They are thought to be due to a combination of biological, psychological, interpersonal, and healthcare factors, and commonly present as pain, headaches, fatigue, chest pain, stomachaches, dizziness, or insomnia. The estimated prevalence of somatic symptoms in children and adolescents is between 10–30%. (2,3)

Somatic symptoms can significantly impair patients’ lives. Adults with somatic symptoms report greater distress, decreased quality of life, and increased social isolation compared to patients who receive a medical diagnosis. (4) In children, somatic symptoms have been associated with emotional and behavioral problems, school absences, and social impairments.(5–7) Furthermore, individuals with somatic symptoms are high utilizers of the healthcare system and account for a substantial amount of health care costs.(8)

In adults, somatic symptoms have been associated with exposure to familial illness.(9) Furthermore, some literature has shown evidence of somatic symptoms in children and adolescents who have family members with cancer. Specifically, studies have found increased reports of sleep difficulties, headaches, stomachaches, dizziness, and loss of appetite.(10–14) Additionally, a review on the psychosocial impact of cancer on siblings identified a handful of studies which examined either somatic symptoms or physical quality of life. Evidence from this review was mixed, with some studies finding no difference in somatic symptoms in siblings compared to controls, and others finding differences based on sibling age and time since diagnosis. Older children and children whose ill sibling had been diagnosed less recently were more likely than controls to report somatic symptoms. (15)

Social learning theory provides a potential model for the development of somatic symptoms in children and adolescents. Social learning theory suggests somatic symptoms in children may be influenced by family members with a chronic illness in two ways. First, children may learn to display and manage somatic symptoms through a family members’ modeling of the symptoms. Second, family members may reinforce somatic symptoms displayed by children by giving them positive attention or allowing them to miss an undesirable activity (e.g. school) when they experience somatic symptoms(16,17). Research has demonstrated that somatic symptoms are more common in families in which somatic complaints are attended to by family members (18–21), and reinforced or modeled illness behaviors experienced in childhood are associated with higher rates of somatic symptoms in adulthood.(22,23) Based on social learning theory, children may exhibit somatic symptoms in response to any chronic illnesses from which a family member models physical symptoms, especially if the symptom is reinforced in the child.

Based on existing evidence, well-children of family members with a chronic illness may be particularly vulnerable to the development of somatic symptoms. However, the relationship between somatic symptoms and having a chronically ill family member is unclear. To our knowledge, there is no comprehensive systematic review of the literature that examines somatic symptoms in children and adolescents with a family member with any chronic illness. The aim of this article is to provide a systematic review of the existing literature on somatic symptoms in children and adolescents with either a parent or sibling with any chronic illness, evaluate the strength of the evidence based on the available research, and highlight future research directions.

Methods

Systematic Review of the Literature

The following databases were searched for available articles prior to the search date of April 5, 2018: PubMed, EMBASE, PsychINFO, Scopus, CINAHL, and Cochrane. The review was registered with the PROSPERO registry (ID: CRD42018092344) and can be viewed at http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO.

Inclusion Criteria

Humans

English language articles

Participants 17 years or younger, with a parent or sibling diagnosed with any chronic illness.

Studies measuring somatic symptoms or similar terms (e.g., medically unexplained symptoms)

Studies comparing to a healthy control or normative data.

Published prior to April 5, 2018

Exclusion Criteria

Studies were excluded if they were not English language articles, participants were adults, or participants had a chronic illness. Additionally, studies were excluded if the well-child was not compared to a healthy condition or normative data in order to ensure our review highlighted the unique risk for developing somatic symptoms in this population.

Study Search Terms

An initial general review of the literature identified articles that examined somatic symptoms in adolescents with an ill family member. From these articles, categories of search terms were identified as relevant for the study search strategy. Those categories included a) variations on terms for somatic symptoms, b) variations on chronic illnesses, and c) variations on family terminology. An example of the search syntax used in PubMed is provided in the Supplemental Digital Content.

Study Selection

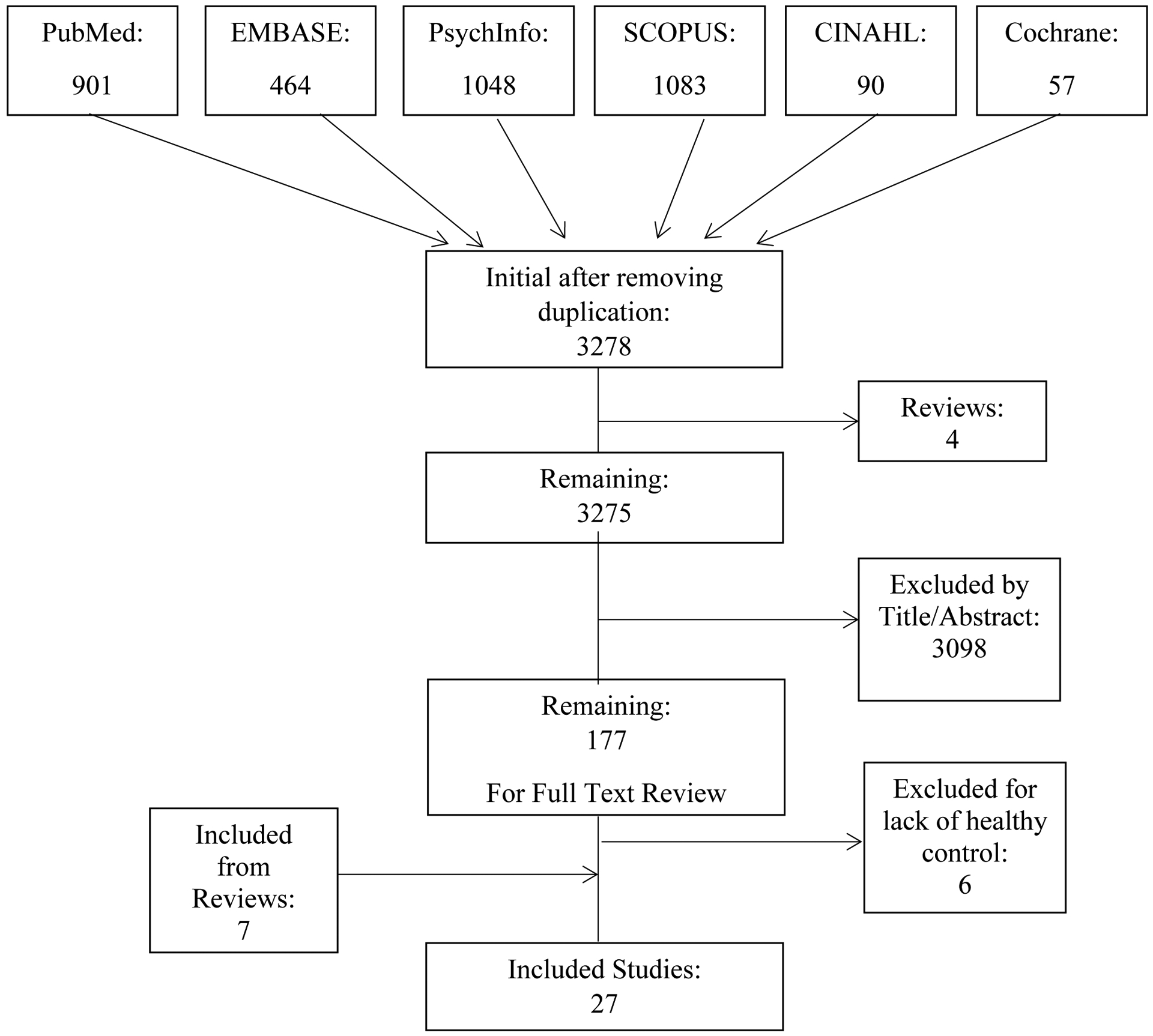

A PRISMA diagram (Figure 1) outlines the search and study selection process. Available articles were first screened by removing duplicates and any non-English language articles that were not screened out by applied filters in the original search. Articles were evaluated by all three authors by title and abstract to determine if each article met inclusion/exclusion criteria prior to retrieving full articles. Full text articles were then reviewed by the same three authors.

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram and study search and selection process.

Risk of Bias Assessment

All included studies were evaluated for risk of bias. Two authors independently reviewed each paper using the RTI Item Bank, which was developed specifically for identifying sources of bias and confounding in observational studies. Specifically the RTI Item Bank evaluates selection, performance, detection and attrition biases, confounding, selective outcome reporting, and overall quality of a study to determine the confidence of a reviewer that the observed effect in a study is the true effect.(24) Following independent review, ratings were compared between the two authors; no significant discrepancies were found between raters.

Results

Results of Literature Search

Twenty-seven unique studies were found that met all search criteria. Seventeen examined the relationship between somatic symptoms and having a parent with a chronic illness, (12,25–41) and seven evaluated the relationship between somatic symptoms and having a sibling with chronic illness.(42–48) Additionally, we identified three studies which examined somatic symptoms in children with an ill relative but did not specify which relative was ill.(49–51)

During the course of this review, three review papers were found which examined general psychosocial outcomes in adolescents with an ill family member. While these reviews did not comprehensively evaluate somatic symptoms in this population, three articles from these reviews were identified as meeting inclusion criteria and have been included in this systematic review.

Results of Parent Chronic Illness

Seventeen studies examined the relationship between somatic symptoms and having a parent with a chronic illness (Table 1). Thirteen studies found a significant positive association between having a parent with chronic illness and somatic symptoms.(25–27,29,30,32,33,37,39–41,52,53) Of those thirteen studies, two examined somatic symptoms in children of parents with AIDS. Asanbe et al. found that South African children orphaned due to AIDS were at higher risk for somatic problems when compared to healthy controls who had not been orphaned. (25) Similarly, Cluver et al. reported that South African orphans due to AIDS were more likely to report stomachaches, headaches, or illness than controls matched for neighborhood, ethnicity, age and sex.(29) One study examined somatic symptoms in Australian children of parents with multiple sclerosis (MS), and found that 8–12 year olds whose parents had MS reported more somatic symptoms than controls with healthy parents matched for sex, age, siblings, family structure, youth employment, residence, and SES.(33) Three studies were identified which examined somatic symptoms in children with a parent with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Levy and colleagues examined children of parents with IBS in two different studies. The first study found that children whose parents had IBS were more likely to make ambulatory clinic visits compared to controls with healthy parents, and those visits were more likely to be for gastrointestinal symptoms.(38) Their second study found that children of parents with IBS report more bothersome gastrointestinal symptoms than controls with parents who were not diagnosed with a gastrointestinal condition. Similarly, van Tilburg et al., found that children of parents with IBS report more non-gastrointestinal and gastrointestinal symptoms than healthy controls.(39) Additionally, seven studies examined the relationship between somatic symptoms in children and the general health of their parents but did not specify which illness the parent had. Berntsson et al. examined psychosomatic complaints in Swedish children, and found that mother’s health status predicted somatic complaints in their children.(26,27) Hotopf and colleagues reported a strong positive association between persistent abdominal pain in children from the United Kingdom and their parents’ ratings of their health.(30) Similarly, a study examined differences between Swedish children with and without recurrent abdominal pain (RAP) and found that children with RAP were more likely to have parents with poor self-reported health.(32) Walker and colleagues found that children with RAP were more likely to have relatives with abdominal disorders and more likely to live with a relative who had a serious health problem.(40) Another study examined differences in Canadian adolescents referred to an outpatient psychiatry clinic with and without a parent with a physical illness; Morgan et al. found that children who had parents with a self-reported illness of greater than six months reported more somatic symptoms compared to children whose parents were healthy.(52) In a study examining the relationship between maternal health problems and child behaviors, Stein et al. found that maternal physical symptoms and subjective health significantly predicted somatic symptoms in their children.(37)

Table 1.

Parental Chronic Illness and Somatic Symptoms

| Source | Study Design | Sample Country and N | Age Range/Mean (SD) | Parental Disease | Somatic Symptom Measurement | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asanbe (2016) | Cross-Sectional | South Africa 119 | 6–10 | HIV/AIDS | CBCL | Orphans of parents who died of AIDS at higher risk for somatic symptoms |

| Berntsson (2000) | Cross-Sectional | Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden 803 | 7–12 | Somatic complaints and chronic illness | Frequency and severity of psychosomatic complaints (stomachache, headache, sleeplessness, dizziness, backache, loss of appetite) | Mother’s health status predicts somatic complaints |

| Berntsson (2001) | Cross-Sectional | Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden 3,760 | 7–12 | Somatic complaints and long-term illness/disability | Frequency and severity of psychosomatic complaints (stomachache, headache, sleeplessness, dizziness, backache, loss of appetite) | Mother’s health status best predictor of somatic complaints; this relationship was highest in Norway |

| Bursch (2008) | Longitudinal | United States 409 | 15.25 (2.05) | HIV/AIDS | Brief Symptom Inventory | At baseline, somatic symptoms lower than standardization sample Adolescent predictors of somatic symptoms: younger and female; Latino; increased hospitalizations, stressful life events, less parental care, parent-youth conflict, no experience of parental death |

| Cluver (2006) | Cross-Sectional | South Africa 60 | 6–19 Orphans: 11 Non-orphans: 12 | AIDS | Somatic item from the Emotional Scale of Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire | Orphans more likely to report recurrent stomachaches, headaches or sickness |

| Hotopf (1998) | Longitudinal | United Kingdom 3,637 | 7, 11, 15 and 36 | Asthma, cough, rheumatism, anemia, heart trouble, kidney trouble or other health complaints | Persistent abdominal pain reported at 3 time points (ages 7, 11, and 15) | Strong association between abdominal pain and parental health complaints and parental ratings of health |

| Jeppesen (2013) | Cross-sectional | Norway 143- study 439-control | 13–19 | Cancer | Young-HUNT questionnaire somatic stress symptoms | No difference in somatic symptoms between cases and controls |

| Kohler (2017) | Cross-sectional | Sweden 6,528 | 8 months and 4 years | Parental rating of general health (very good to very poor) | Recurrent abdominal pain (parental report) | Recurrent abdominal pain associated with poorer self-reported parental health |

| Levy (2000) | Cross-sectional | United States 631- study 646-control | 3–14 | IBS | Ambulatory visits for GI symptoms | Children of parents with IBS were more likely to make ambulatory visits for GI symptoms |

| Levy (2004) | Cross-sectional | United States 296- study 335-control | 11.9-study 11.8-control | IBS | Child Symptoms Checklist | Children of parents with IBS more likely to report bothersome GI symptoms |

| Morgan (1992) | Cross-sectional | Canada Ill parent- 50 Controls- 54 | 13–19 | Self-reported parental illness for greater than 6 months | Survey Diagnostic Instrument | Children of ill parent report more somatization than controls |

| Pakenham (2013) | Cross-sectional | Australia MS- 126 Control- 126 | 14.04 | Multiple sclerosis | Brief Symptom Inventory | Significantly more somatization in 8–12 year olds with parents with MS than controls |

| Petanidou (2014) | Cross-sectional | Greece 1,041 | 12–18 | Self-report of general health | Health Behavior in School-aged Children Symptom Checklist | Parental physical health not significantly associated with somatic symptoms |

| Ramos (1998) | Cross-sectional | United States 50 | 4–18 | AIDS | BASC | No significant difference between those affected and unaffected by AIDS on somatization |

| Stein (1994) | Cross-sectional | United States 145 | 4.6 | Physical symptomology and subjective health problems | CBCL | Both maternal physical symptomology and subjective health problems significantly predicted psychosomatic complaints in children |

| Van Tilburg (2015) | Cross-sectional | United States 296-study 240-control | 8–15 | IBS | Child Symptom Checklist | Children of parents with IBS reported more non-GI and GI symptoms |

| Walker (1993) | Cross-sectional | United States 249 | 6–18 | Abdominal disorders or serious health problem | Recurrent Abdominal Pain | Children with RAP had significantly more relatives with abdominal disorders and significantly more relatives in the home with serious health problems |

Four studies found no association between having a parent with a chronic illness and somatic symptoms in the child. Two studies examined the relationship between somatic symptoms in children of parents with HIV/AIDS. Bursch et al. found that at baseline somatic symptoms were similar in children of parents with HIV/AIDS and a standardized sample.(28) Likewise, Ramos found no significant difference in self-reported somatic symptoms in children of parents with AIDS and those with healthy parents.(35) One study examined the relationship in Norwegian teenagers of parents with cancer, and found no difference in somatic symptoms in these teenagers compared to controls matched for sex, age, and municipality.(31) Lastly, Petanidou and colleagues examined family characteristics and their relationship with somatic symptoms in Greek adolescents, and found that parental self-report of health was not associated with somatic symptoms in the adolescents.(34)

Results of Sibling Chronic Illness

Seven studies examined the relationship between having a sibling with a chronic illness and somatic symptoms (Table 2).(42–48) Four studies found a significant positive association between having a sibling with chronic illness and somatic symptoms, (42,44,46,47) three of which examined somatic symptoms in siblings of children with cancer. In a study of healthy Israeli Jewish children with a sibling with cancer, Hamama et al. reported significantly higher average somatic symptom scores in healthy siblings than scores of normative samples. Furthermore, they reported that somatic symptoms in siblings were positively associated with role overload, or the difference between the demands placed on an individual and the resources they have to meet those demands. Somatic symptoms in siblings were also negatively associated with self-control and self-efficacy.(44) Massie found that siblings of children with cancer reported higher somatic symptoms on the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) than normative data.(46) In a study examining sibling adaptation to a childhood cancer diagnosis, Zeltzer and colleagues found that siblings had higher somatic symptoms than non-clinical normative samples, but lower than clinical samples according to both parent and self-report measures. Adolescent boys represented an exception, and reported somatic symptoms scores as high as clinical samples.(47)

Table 2.

Sibling Chronic Illness and Somatic Symptoms

| Source | Study Design | Sample Country and N | Age Range/Mean (SD) | Sibling Disease | Somatic Symptom Measurement | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cadman (1988) | Cross-sectional | Canada 3,294 | 12–16 | Blindness, deafness, severe speech problems, severe pain, asthma, heart problems, epilepsy, kidney disease, arthritis, cerebral palsy, muscular dystrophy, spina bifida, diabetes, cancer, cystic fibrosis, physical deformities | Survey Diagnostic Instrument | Children with sibling with chronic health problems only at small risk of somatization (OR = 1.6) |

| Gold (1999) | Cross-sectional | United States 97- siblings 56- ill children | Siblings 11.24 Ill children 10.41 | Sickle cell disease | CBCL | Report less somatization than ill siblings. Do not have clinically significant levels of somatization when compared to sex matched norms for CBCL |

| Hamama (2008) | Cross-sectional | Israeli Jewish 100 | Siblings 8–19 | Cancer | Frequent symptoms scale | Role overload correlated with somatic symptoms in siblings; somatic symptoms negatively correlated with self-control and self-efficacy |

| Lahteenmaki (2004) | Cross-sectional/repeated measures | Finland 33 siblings 357 healthy controls | 3–17 | Cancer | Huttunen’s test | No difference between siblings and controls on somatic symptoms |

| Massie (2012) | Cross-sectional | Canadian 108 | 7–17 | Cancer | CBCL | Siblings reported higher somatic problems than normative population |

| Von Dongen-Melman (1995) | Cross-sectional | Netherlands 60 | 4–16 | Cancer | Amsterdam Biographic Questionnaire for Children (ABV-K); CBCL | On the ABV-K, siblings reported significantly less somatization than controls. No difference found on CBCL somatization subscale. |

| Zeltzer (1996) | Cross-sectional | United States 254 | 5–18 (10.65) | Cancer | National Health Survey Data; CBCL; Youth Self Report | Parent-reported and sibling self-reported higher somatization than non-clinical norms, but lower than clinical normative samples. Adolescent boys had somatization scores as high as clinical normative scores. Higher sibling somatization associated with higher sibling reported interpersonal adjustment difficulties. |

One study included siblings of children with various illnesses and disabilities (e.g., blindness, asthma, epilepsy, cancer, etc.), and found that siblings of children with chronic health problems were at a small risk for somatic symptoms.(42)

Three studies found either no significant association or an inverse relationship between having a sibling with chronic illness and somatic symptoms when compared to control groups. Two of these studies examined siblings of children with cancer. Lahteenmaki et al. examined outcomes of Finnish children with a sibling diagnosed with cancer, and found no difference between siblings and a control group on somatic symptoms.(45) Similarly, Van Dongen-Melman and colleagues found no difference between Dutch siblings of children who had successfully completed treatment for cancer and controls on somatic symptoms as measured by the CBCL. Additionally, they demonstrated that siblings reported significantly less somatic symptoms than controls on the Amsterdam Biographic Questionnaire for Children.(48) Gold examined adjustment in siblings of children diagnosed with sickle cell, and showed that siblings did not report clinically significant levels of somatic symptoms compared to sex matched normative data on the CBCL.(43)

Results of Unspecified Relatives

Three studies examined the relationship between having an ill relative and somatic symptoms, without identifying which relative was ill (Table 3).(49–51) Domench-Llaberia et al. reported that children who frequently complained of somatic symptoms were more likely to have relatives with a chronic illness, most commonly asthma, than those who did not complain frequently.(50) Poikolainen and colleagues reported that a serious illness or injury in a family member predicted somatic symptoms in females.(49) Finally, Moffat et al. found that a larger percentage of youth reported somatic symptoms when there were family health concerns present than when no concerns were present. However, youth somatic symptoms were lower when the family health concerns were disability and chronic illness than when they were depression, mental illness, or alcohol and drug use.(51)

Table 3.

Relative not Specified

| Source | Study design | Subjects (n) | Age range/mean | Relative Disease | Somatic Symptom Measurement | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domenech (2004) | Cross-Sectional | Spain 807 | 3–5 | Illness in relative | Researcher designed questionnaire | More children in the frequently complaining group had relatives with chronic illness (most often asthma) |

| Poikolainen (1995) | Cross-Sectional | Finland 790 female 639 male | 14–20 | Serious illness or injury | Researcher designed 18 item symptom score | Serious illness or injury significantly predicted somatic symptoms among females |

| Moffat (2017) | Cross-sectional | Australia 5,377 | 9–14 | Family member seriously affected with disability or long term illness; depression or mental illness; using alcohol or drugs | HBSC Symptom Checklist | Greater percentage of youth with family health concerns report symptoms than those without family health concerns (significance not reported). Proportion of symptom load is lowest for disability or chronic illness |

Results of Risk of Bias

Two studies merited high risk of bias (26,27), and 25 merited moderate risk of bias. This was primarily due to the nature of the design of the studies. The majority of the studies were cross-sectional in nature, limiting the conclusions which can be drawn from the results of these studies. The exclusion criteria of the current review (i.e., requiring a healthy comparison group) may have eliminated several studies with high risk of bias.

Discussion

Although research is limited, there appears to be evidence of increased somatic symptoms in children with a family member with a chronic illness, with the strongest evidence favoring a relationship between a parent with a chronic illness and childhood somatic symptoms. The majority of existing literature examining an ill parent and somatic symptoms in children reported an association between having an ill parent and somatic symptoms, with thirteen out of seventeen studies reporting a significant relationship.

These findings are consistent with other research supporting the role of social learning theory in the development of somatic symptoms in children with an ill parent. Although genetics can contribute to the transmission of symptoms, one study compared the contribution of heredity versus social learning. In a study of 11,986 monozygotic and dizygotic twins, Levy and colleagues found heredity and social learning to have an equal contribution in the development of IBS in children with parents diagnosed with IBS.(54) Additionally, several of the reviewed studies found that the somatic symptoms displayed in children were similar to the symptoms experienced by the ill parent. For example, Levy and colleagues found that children of parents with IBS were more likely to exhibit gastrointestinal symptoms(38,41), and Walker and colleagues demonstrated an increase in RAP in children with a parent with an abdominal disorder.(40) This suggests children may be more likely to experience symptoms which are directly modeled by parents. Furthermore, parents may be more likely to attend to and reinforce physical symptoms similar to those that they have experienced in their own chronic illness.

The evidence regarding the relationship between having a sibling with a chronic illness and somatic symptoms was somewhat mixed. Four studies reported a significant relationship between having an ill sibling and somatic symptoms, (42,44,46,47) and three studies reported no relationship or an inverse relationship.(43,45,48) The majority of studies examining the relationship between having an ill sibling and somatic symptoms were conducted in siblings of children with cancer,(44–48) limiting the generalizability of the results to other disorders. Of the studies examining children with a sibling diagnosed with cancer, a significant relationship between having an ill sibling and somatic symptoms was found in studies comparing outcomes to normative data but not when compared to a matched healthy control population. This may contribute to the mixed literature on this relationship.

The difference in somatic symptoms in children with an ill parent versus an ill sibling is notable. While any familial illness could potentially result in learned illness behavior, parent modeling of symptoms may be more salient to child and adolescent learning than modeling by other family members. Previous literature has suggested that adults are stronger models for learning than their peers or siblings.(55) This could be due to the fact that the parent has more control over rewards and consequences related to illness behaviors (e.g., parent may allow or disallow a child to miss school). One study suggests that this relationship may also be stronger when the children are of the same sex as the ill parent. In a study examining somatic symptoms in Turkish adolescents with parents diagnosed with cancer, they reported greater somatic symptoms in males than females when the ill parent was the father compared to the mother. (56) Additionally, research on social learning theory suggests several factors which may influence learned behavior. In particular, older siblings and siblings of the same sex are more likely to serve as models than other sibling dyads. (57) These differences in social learning from siblings may explain, at least in part, the mixed nature of the sibling literature found in this review.

Finally, three studies examined somatic symptoms in children without specifying which relative was ill. All three studies found evidence for a relationship between having an ill relative and somatic symptoms.(49–51) This effect was found across each of the studies despite the variations in age range and method of symptom measurement.

There are several clinical implications from this review. These findings suggest that having an ill family member is related to somatic symptoms in children, with the strongest evidence for ill parents. Therefore, children with ill family members would benefit from prevention and early intervention methods to minimize the effects associated with having an ill family member. Medical professionals can educate parents with a chronic illness about the potential effects of the illness on their children. Parents can be encouraged to monitor their children for increased somatic symptoms and instructed how to avoid reinforcement of somatic symptoms. Early intervention may decrease distress for the child and family and have larger implications on the health care system, as somatic symptoms have been associated with greater medical care utilization and increased medical costs.(58) Additionally, programs can be developed for children with a family member with a chronic illness which provide coping skills and support in order to prevent the development of somatic symptoms. Interventions for somatic symptoms can specifically address parental reinforcement of symptoms and symptom modeling in children with a family member with a chronic illness. Finally, as future research further elucidates this relationship, the understanding of additional mediators and moderators may allow for specific interventions that target the most at-risk families and strengthen potential protective factors.

Future Research Directions

A significant outcome of this review is the delineation of many areas which necessitate future research to further the understanding of somatic symptoms in children with a chronically ill family member. First, we suggest future studies examine somatic symptoms as a primary outcome. Second, research should assess all chronic illnesses as etiological factors for the development of somatic symptoms rather than focusing on individual illnesses. Somatic symptoms may be developed from any physical symptoms modeled by family members, and including all chronic illnesses will allow for the assessment of the overall effect of familial chronic illness on somatic symptoms in children. Furthermore, research can prospectively measure the impact of familial chronic illness by beginning to assess somatic symptoms in children and siblings of those with a chronic illness at the time of their diagnosis. This would allow for a stronger evidence based etiological model of somatic symptoms as a learned illness behavior.

There are also several parental factors which may mediate or moderate the relationship between somatic symptoms in children and parent or sibling illness that need additional investigation. First, parenting style may impact whether somatic symptoms are learned by a child. One study found that across several cultures, higher parental warmth predicted lower somatic symptoms.(59) Furthermore, parenting styles differ by culture, possibly leading to differing relationships between child somatic symptoms and parental illness among cultures. Co-morbid parental mental health diagnoses may also significantly impact this relationship. There is evidence to suggest that depressed and/or anxious mothers display decreased parental warmth,(60) which is associated with increased somatic symptoms.(59,60) There is also evidence of both a genetic and a learned behavioral component to the transmission of anxiety and depression from parent to child, with children with anxious or depressed parents more likely to have the disorders themselves and engage in maladaptive thought patterns.(60,61) Since anxiety and depression are related to increased somatic symptoms, these symptoms may be similarly transmitted to their children.(62)

In addition to parental characteristics, sibling characteristics may play a role. Future studies should examine the effect of having an older versus a younger sibling with a chronic illness on somatic symptoms in children, as modeling of symptoms by older siblings may be more salient than in younger siblings. As previously mentioned, research has shown that adults have a larger effect on learned behaviors than peers or siblings, possibly due to increased control of rewards and consequences of behaviors.(55) It is possible that older siblings also have some control over access to rewards and consequences for behaviors, though not to the same extent as parents.

Characteristics of the well-child may also affect learning of somatic symptoms, and future research should address if all children in the household are affected similarly by the presence of an ill family member. There is evidence that females are more susceptible to learning behaviors compared to their male peers.(40,63) Other child characteristics which may be important to examine could include co-morbid anxiety or depression and child temperament (e.g., assertive children may be less likely to internalize modeled behaviors).

Finally, symptomology of the ill parent or sibling may also have an impact. Chronic illnesses which have been found to be transmitted through both genetic factors and social learning, such as IBS (54), may result in more somatic symptoms than those that are not transmitted through social learning (e.g. cancer). Additionally, there is evidence in the IBS literature that children of parents with IBS display similar symptomology in the absence of an IBS diagnosis.(38,41) This could suggest that children are more likely to display the symptoms directly modeled by the ill family member, and symptoms which are more overt (e.g., vomiting) may be more salient than symptoms which are less visible (e.g., dizziness). Additionally, duration of illness may impact the relationship between having an ill family member and somatic symptoms. Previous research in learning theory and depression suggests that duration of time spent with a depressed parent was related to child outcomes.(64,65) This suggests that increased exposure to parental behavior may result in longer periods of modeling and reinforcement with other behavioral outcomes, such as somatic symptoms, in the child. Learning may also be more salient when there is more significant impairment in the ill family member. Therefore, chronic illnesses which impact daily life more significantly or for longer periods of time (e.g. cystic fibrosis) may result in more significant somatic symptoms. This may increase the child’s exposure to these symptoms as well as provide models of potential secondary gain of symptoms. Similarly, somatic symptoms may differ between children whose parent died of a chronic illness and those who continue to live with a chronically ill parent. Future research should assess the severity of chronic illness in the family member on the development of somatic symptoms in children.

This review has several strengths. First, we provided a comprehensive systematic review of the existing literature on having a relative with an illness and somatic symptoms in children and adolescents. To our knowledge this is the first systematic review to do so. Second, while the majority of the literature focuses on a single family chronic illness as an etiological factor for somatic symptoms in children and adolescents, this review is unique in that it included any chronic illness which met criteria. Finally, this study outlines the mixed nature of the current literature, especially for siblings of those with chronic illnesses, and it highlights the need for continued study of somatic symptoms in children who have a relative with a chronic illness.

The literature on somatic symptoms in children with an ill family member is somewhat limited and has several weaknesses. First, there were several studies which relied on self-report ratings of health rather than specific diagnoses, at least in the parent illness literature. (26,27,32,34,37,52) Furthermore, many studies focused on a single chronic illness, such as cancer or AIDS, limiting the generalizability of those studies. Also, a variety of measures were used to assess somatic symptoms in children and adolescents, ranging from self-reported symptomology to validated measures with somatization subscales. Similarly, only a handful of the studies (40,50,66) explicitly excluded children diagnosed with other health conditions, which could confound the findings of this review as somatic symptoms may instead be due to organic physical conditions in some of the participants. This is likely due to somatic symptoms not being the primary outcome measured by these studies, but rather a secondary finding. Despite this, many of the studies that did not control for other health conditions utilized measures of somatic symptoms which have scores comparable to normative data for somatic symptoms. The overwhelming majority of studies were cross-sectional and did not examine the longitudinal effects of having a parent or sibling with a chronic illness. In part due to study design, the literature included in this review all exhibited moderate to high risk of bias, suggesting a need for more rigorous study in this area. In addition, the sibling literature primarily focused on children diagnosed with cancer limiting the generalizability. Of note, many of the studies included in this review were not directly assessing somatic symptoms but included information regarding somatic symptoms as an indirect finding or in relation to overall psychosocial functioning. There were also a limited number of studies identified. However, every effort was made to identify appropriate search terms which included a) variations on terms for somatic symptoms, b) variations on chronic illnesses, and c) variations on family terminology. Given that the search terms resulted in 3,278 articles, these authors do not believe that the search terms used were overly limiting. This review only included studies using a healthy control population in order to determine significant differences between our population and the general population.

Conclusions

This systematic review highlights the relationship between having a chronically ill family member and somatic symptoms in children, especially among children of a parent with a chronic illness, and the need for continued research on the relationship. Based on social learning theory, any familial illness diagnosis could result in modeling of illness behaviors or reinforcement of illness behaviors by family members. Results indicate the strongest support for a relationship between having an ill parent and somatic symptoms. However, further research including a wider range of chronic illnesses is needed. Similarly, the research regarding having an ill sibling could benefit from expanding disease populations beyond research in cancer. Additionally, this review calls for further research that is longitudinal in nature, following the course of the disease from diagnosis to remission and survivorship. Implications of this review include targeted prevention and treatment for somatic symptoms in children with family members with a chronic illness.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We would like to thank Carolyn Holmes and Geeta Malik with the Lister Hill Library at the University of Alabama at Birmingham for their assistance in developing the search strategy for this review.

Funding Source: Dr. Fobian’s work on this project was supported by Award Number 1K23DK106570-01A1 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disaeses. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIDDK or the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations:

- MS

Multiple Sclerosis

- RAP

recurrent abdominal pain

- CBCL

Child Behavior Checklist

- IBS

irritable bowel syndrome

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Potential Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interests relevant to this article to disclose.

References

- 1.Bonvanie IJ, Janssens KAM, Rosmalen JGM, Oldehinkel AJ. Life events and functional somatic symptoms: A population study in older adolescents. British Journal of Psychology. 2017;108(2):318–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geist R, Weinstein M, Walker L, Campo JV. Medically unexplained symptoms in young people: The doctor’s dilemma. Paediatrics & Child Health. 2008;13(6):487–491. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mayou R, Farmer A. ABC of psychological medicine: Functional somatic symptoms and syndromes. BMJ: British Medical Journal. 2002;325(7358):265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dirkzwager AJE, Verhaak PFM. Patients with persistent medically unexplained symptoms in general practice: characteristics and quality of care. BMC Family Practice. 2007;8(1):33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strine TW, Okoro CA, McGuire LC, Balluz LS. The Associations Among Childhood Headaches, Emotional and Behavioral Difficulties, and Health Care Use. Pediatrics. 2006;117(5):1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Konijnenberg A, Uiterwaal C, Kimpen J, van der Hoeven J, Buitelaar J, de Graeff-Meeder E. Children with unexplained chronic pain: substantial impairment in everyday life. Archives of disease in childhood. 2005;90(7):680–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rask CU, Olsen EM, Elberling H, Christensen MF, Ørnbøl E, Fink P, Thomsen PH, Skovgaard AM. Functional somatic symptoms and associated impairment in 5–7-year-old children: the Copenhagen Child Cohort 2000. European journal of epidemiology. 2009;24(10):625–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reid S, Wessely S, Crayford TIM, Hotopf M. Frequent attenders with medically unexplained symptoms: service use and costs in secondary care. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;180(3):248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hotopf Matthew, Mayou Richard, Wadsworth Michael, Wessely Simon. Childhood Risk Factors for Adults With Medically Unexplained Symptoms: Results From a National Birth Cohort Study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156(11):1796–1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heiney SP, Bryant LH, Walker S, Parrish RS, Provenzano FJ, Kelly KE. Impact of parental anxiety on child emotional adjustment when a parent has cancer. Paper presented at: Oncology nursing forum1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hilton B, Elfert H. Children’s experiences with mothers’ early breast cancer. Cancer Practice. 1996;4(2):96–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christ GH, Siegel K, Freund B, Langosch D, Hendersen S, Sperber D, Weinstein L. Impact of parental terminal cancer on latency-age children. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1993;63(3):417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenfeld A, Caplan G, Yaroslavsky A, Jacobowitz J, Yuval Y, LeBow H. Adaptation of children of parents suffering from cancer: a preliminary study of a new field for primary prevention research. The journal of primary prevention. 1983;3(4):244–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spira M, Kenemore E. Adolescent daughters of mothers with breast cancer: Impact and implications. Clinical Social Work Journal. 2000;28(2):183–195. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alderfer MA, Long KA, Lown EA, Marsland AL, Ostrowski NL, Hock JM, Ewing LJ. Psychosocial adjustment of siblings of children with cancer: a systematic review. Psycho-Oncology. 2010;19(8):789–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whitehead WE, Fedoravicius AS, Blackwell B, Wooley S. A behavioral conceptualization of psychosomatic illness: Psychosomatic symptoms as learned responses In: Behavioral approaches to medicine. Springer; 1979:65–99. [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Gucht V, Maes S. Explaining medically unexplained symptoms: toward a multidimensional, theory-based approach to somatization. Journal of psychosomatic research. 2006;60(4):349–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schanberg LE, Anthony KK, Gil KM, Lefebvre JC, Kredich DW, Macharoni LM. Family pain history predicts child health status in children with chronic rheumatic disease. Pediatrics. 2001;108(3):e47–e47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beck JE. A developmental perspective on functional somatic symptoms. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2007;33(5):547–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hill OW, Blendis L. Physical and psychological evaluation of’non-organic’abdominal pain. Gut. 1967;8(3):221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walker LS, Garber J, Greene JW. Somatization symptoms in pediatric abdominal pain patients: relation to chronicity of abdominal pain and parent somatization. Journal of abnormal child psychology. 1991;19(4):379–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lowman BC, Drossman DA, Cramer EM, McKee DC. Recollection of childhood events in adults with irritable bowel syndrome. Journal of clinical gastroenterology. 1987;9(3):324–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Whitehead WE, Crowell MD, Heller BR, Robinson JC, Schuster MM, Horn S. Modeling and reinforcement of the sick role during childhood predicts adult illness behavior. Psychosomatic medicine. 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Viswanathan M, Berkman ND, Dryden DM, Hartling L. Assessing Risk of Bias and Confounding in Observational Studies of Interventions or Exposures: Further Development of the RTI Item Bank. In: Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asanbe C, Moleko A-G, Visser M, Thomas A, Makwakwa C, Salgado W, Tesnakis A. Parental HIV/AIDS and psychological health of younger children in South Africa. Journal of Child & Adolescent Mental Health. 2016;28(2):175–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berntsson LT, Gustafsson JE. Determinants of psychosomatic complaints in Swedish schoolchildren aged seven to twelve years. Scandinavian journal of public health. 2000;28(4):283–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berntsson LT, Köehler L, Gustafsson JE. Psychosomatic complaints in schoolchildren: A Nordic comparison. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2001;29(1):44–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bursch B, Lester P, Jiang L, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Weiss R. Psychosocial predictors of somatic symptoms in adolescents of parents with HIV: a six-year longitudinal study. AIDS care. 2008;20(6):667–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cluver L, Gardner F. The psychological well-being of children orphaned by AIDS in Cape Town, South Africa. Annals of General Psychiatry. 2006;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hotopf M, Carr S, Mayou R, Wadsworth M, Wessely S. Why do children have chronic abdominal pain, and what happens to them when they grow up? Population based cohort study. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 1998;316(7139):1196–1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jeppesen E, Bjelland I, Fossa SD, Loge JH, Dahl AA. Psychosocial problems of teenagers who have a parent with cancer: a population-based case-control study (young-HUNT study). Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31(32):4099–4104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kohler M, Emmelin M, Rosvall M. Parental health and psychosomatic symptoms in preschool children: A cross-sectional study in Scania, Sweden. Scandinavian journal of public health. 2017:1403494817705561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pakenham KI, Cox S. Comparisons between youth of a parent with MS and a control group on adjustment, caregiving, attachment and family functioning. Psychology & health. 2013;29(1):1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Petanidou D, Mihas C, Dimitrakaki C, Kolaitis G, Tountas Y. Selected family characteristics are associated with adolescents’ subjective health complaints. Acta paediatrica (Oslo, Norway : 1992). 2014;103(2):201–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramos C Mental health factors in healthy children and adolescents affected by a parent’s human immunodeficiency virus (hiv)/acquired immune deficiency syndrome 1998.

- 36.Rizzo TA, Silverman BL, Metzger BE, Cho NH. Behavioral adjustment in children of diabetic mothers. Acta paediatrica (Oslo, Norway : 1992). 1997;86(9):969–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stein JA, Newcomb MD. Children’s internalizing and externalizing behaviors and maternal health problems. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 1994;19(5):571–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Levy RL, Whitehead WE, Walker LS, Von Korff M, Feld AD, Garner M, Christie D. Increased somatic complaints and health-care utilization in children: effects of parent IBS status and parent response to gastrointestinal symptoms. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2004;99(12):2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Tilburg MA, Levy RL, Walker LS, Von Korff M, Feld LD, Garner M, Feld AD, Whitehead WE. Psychosocial mechanisms for the transmission of somatic symptoms from parents to children. World Journal of Gastroenterology: WJG. 2015;21(18):5532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walker LS, Garber J, Greene JW. Psychosocial correlates of recurrent childhood pain: a comparison of pediatric patients with recurrent abdominal pain, organic illness, and psychiatric disorders. Journal of abnormal psychology. 1993;102(2):248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Levy RL, Whitehead WE, Von Korff MR, Feld AD. Intergenerational transmission of gastrointestinal illness behavior. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2000;95(2):451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cadman D, Boyle M, Offord DR. The Ontario Child Health Study: social adjustment and mental health of siblings of children with chronic health problems. Journal of developmental and behavioral pediatrics : JDBP. 1988;9(3):117–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gold JI. Psychological adjustment in siblings of children with sickle cell disease: Relationships with family and sibling adaptational processes.(African-Americans) 1999.

- 44.Hamama L, Ronen T, Rahav G. Self-control, self-efficacy, role overload, and stress responses among siblings of children with cancer. Health & social work. 2008;33(2):121–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lahteenmaki PM, Sjoblom J, Korhonen T, Salmi TT. The siblings of childhood cancer patients need early support: a follow up study over the first year. Archives of disease in childhood. 2004;89(11):1008–1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Massie KJ. Frequency and predictors of sibling psychological and somatic difficulties following pediatric cancer diagnosis 2012.

- 47.Zeltzer LK, Dolgin MJ, Sahler OJ, Roghmann K, Barbarin OA, Carpenter PJ, Copeland DR, Mulhern RK, Sargent JR. Sibling adaptation to childhood cancer collaborative study: health outcomes of siblings of children with cancer. Medical and pediatric oncology. 1996;27(2):98–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van Dongen-Melman J, De Groot A, Hählen K, Verhulst F. Siblings of childhood cancer survivors: How does this “forgotten” group of children adjust after cessation of successful cancer treatment? European Journal of Cancer. 1995;31(13–14):2277–2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Poikolainen K, Kanerva R, Lonnqvist J. Life events and other risk factors for somatic symptoms in adolescence. Pediatrics. 1995;96(1 Pt 1):59–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Domenech-Llaberia E, Jane C, Canals J, Ballespi S, Esparo G, Garralda E. Parental reports of somatic symptoms in preschool children: prevalence and associations in a Spanish sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43(5):598–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moffat AK, Redmond G. Is having a family member with chronic health concerns bad for young people’s health? Cross-sectional evidence from a national survey of young Australians. BMJ open. 2017;7(1):e013946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Morgan J, Sanford M, Johnson C. The impact of a physically ill parent on adolescents: cross-sectional findings from a clinic population. Canadian journal of psychiatry Revue canadienne de psychiatrie. 1992;37(6):423–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Levy RL, Whitehead WE, Walker LS, Von Korff M, Feld AD, Garner M, Christie D. Increased somatic complaints and health-care utilization in children: effects of parent IBS status and parent response to gastrointestinal symptoms. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2004;99(12):2442–2451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Levy RL, Jones KR, Whitehead WE, Feld SI, Talley NJ, Corey LA. Irritable bowel syndrome in twins: heredity and social learning both contribute to etiology. Gastroenterology. 2001;121(4):799–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bandura A, Kupers CJ. Transmission of patterns of self-reinforcement through modeling. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 1964;69(1):1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kucukoglu S, Celebioglu A. Identification of psychological symptoms and associated factors in adolescents who have a parent with cancer in Turkey. European journal of oncology nursing : the official journal of European Oncology Nursing Society. 2013;17(1):75–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Whiteman SD, McHale SM, Soli A. Theoretical perspectives on sibling relationships. Journal of family theory & review. 2011;3(2):124–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Barsky AJ, Orav EJ, Bates DW. Somatization increases medical utilization and costs independent of psychiatric and medical comorbidity. Archives of general psychiatry. 2005;62(8):903–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rothenberg WA, Lansford JE, Al-Hassan SM, Bacchini D, Bornstein MH, Chang L, Deater-Deckard K, Di Giunta L, Dodge KA, Malone PS. Examining effects of parent warmth and control on internalizing behavior clusters from age 8 to 12 in 12 cultural groups in nine countries. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Whaley SE, Pinto A, Sigman M. Characterizing interactions between anxious mothers and their children. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 1999;67(6):826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.River LM, Borelli JL, Vazquez LC, Smiley PA. Learning helplessness in the family: Maternal agency and the intergenerational transmission of depressive symptoms. Journal of Family Psychology. 2018;32(8):1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Haug TT, Mykletun A, Dahl AA. The association between anxiety, depression, and somatic symptoms in a large population: the HUNT-II study. Psychosomatic medicine. 2004;66(6):845–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chambers CT, Craig KD, Bennett SM. The impact of maternal behavior on children’s pain experiences: An experimental analysis. Journal of pediatric psychology. 2002;27(3):293–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Blount TH, Epkins CC. Exploring modeling-based hypotheses in preadolescent girls’ and boys’ cognitive vulnerability to depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2009;33(1):110–125. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Trapolini T, McMahon CA, Ungerer JA. The effect of maternal depression and marital adjustment on young children’s internalizing and externalizing behaviour problems. Child: care, health and development. 2007;33(6):794–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Poikolainen K, Kanerva R, Lönnqvist J. Life events and other risk factors for somatic symptoms in adolescence. Pediatrics. 1995;96(1):59–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.