Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Self-reported weight change may lead to adverse outcomes. We evaluated weight change with cutpoints of low lean mass (LLM) in older adults.

METHODS:

Of 4,984 subjects ≥60 years from NHANES 1999-2004, we applied LLM cutoffs of appendicular lean mass (ALM):body mass index (BMI) males<0.789, females<0.512. Self-reported weight was assessed at time of survey, and questions asked participants their weight one and 10 years earlier, and at age 25. Weight changes were categorized as greater/less/none than 5%. Logistic regression assessed weight change (gain, loss, no change) on LLM, after adjustment.

RESULTS:

Of 4,984 participants (56.5% female), mean age and BMI were 71.1 years and 28.2 kg/m2. Mean ALM was 19.7kg. In those with LLM, 13.5% and 16.3% gained/lost weight in the past year, while 48.9% and 19.4% gained/lost weight in the past decade. Compared to weight at age 25, 85.2 and 6.1% of LLM participants gained and lost ≥5% of their weight, respectively. Weight gain over the past year was associated with a higher risk of LLM (OR 1.35 [0.99,1.87]) compared to weight loss ≥5% over the past year (0.89 [0.70,1.12]). Weight gain (≥5%) over 10-years was associated with a higher risk of LLM (OR 2.03 [1.66, 2.49]) while weight loss (≥5%) was associated with a lower risk (OR 0.98 [0.76,1.28]). Results were robust compared to weight at 25 years (gain OR 2.37 [1.76,3.20]; loss OR 0.95 [0.65,1.39]).

CONCLUSION:

Self-reported weight gain suggests an increased risk of LLM. Future studies need to verify the relationship with physical function.

Keywords: low lean mass, sarcopenia, self-reported weight, epidemiology

INTRODUCTION

Sarcopenia, defined as the loss of muscle mass, strength, and function, is a natural phenomenon of aging that occurs after age 60[1]. While the definition of sarcopenia has changed over the years, the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (FNIH) proposed definitions for low lean mass (LLM) in 2014 that identified a causal, indirect relationship between muscle mass and physical function[2]. Reduced muscle mass, specifically low appendicular lean muscle mass (ALM), is associated with impaired physical function[2], cardiovascular disease[3], and mortality[4]. Ascertaining muscle mass requires body composition measurement methods that are not ordinarily available or reimbursable in many primary care outpatient practices. Hence, pragmatic and alternative measurement methods are needed to assist with identification of individuals at risk for impairment and morbidity due to LLM.

Weight is routinely measured within ambulatory infrastructures, often as part of pre-visit evaluations by support staff in conjunction with other vital signs[5, 6]. Objective weight changes documented within electronic medical records, without knowing if intentional or not, may indicate efforts in improving one’s health, weight cycling, or may be a harbinger of adverse medical events[7–10]. These changes can provide opportunities for practicing clinicians to identify different trajectories, particularly among long-standing patients with many years of medical record data. While weight gain and changes in body composition occur with each decade of life, often peaking in the 6th or 7th decades[11], the extent to which these changes may impact the development of LLM and functional limitations is unknown. Weight changes may provide an opportunity for additional targeted interventions for high-risk older adults whose reserve capacity is minimal[12], and where physiologic disturbances can prompt medical attention.

To our knowledge, it is unknown whether changes in weight, independent of intentionality, place individuals at risk for LLM using the current FNIH consensus definitions. In the Health, Aging and Body Composition cohort, weight loss over a 4-year period was associated with muscle mass loss in both sexes, but this was limited to individuals aged 70-79 years[13]. It is also unclear how weight changes over the life course could impact the development of LLM. Such information can assist in prognostication by engaging individuals in health promotion strategies that mitigate its development. The purpose of this study was to evaluate weight change trajectories for the risk of developing LLM among a representative cohort of United States adults.

MATERIALS & METHODS

Study Design

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) are cross-sectional surveys administered by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that are used to evaluate disease-specific epidemiologic changes among the United States population. NHANES data have informed policy changes over the past 5 decades and are currently released in 2-year intervals. The survey design oversamples older adults and minorities and relies on a multistage, complex stratified probability sampling. Results are therefore generalizable to the United States population. All manuals, procedures and data files are publically available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.html. The Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at Dartmouth deems secondary analyses of de-identified public research as exempt.

Participant Sample Size

Individuals were screened (n=38,077) and completed standardized questionnaires. A select number were interviewed (n=31,125) and then examined in a mobile examination unit by a trained physician and staff (n=29,402). We limited our cohort to individuals aged 60 years and older as our previous work has demonstrated that the prevalence of LLM is significantly lower among younger populations[4, 14]. The cohort was also restricted to individuals with body composition measures (see below) limiting our sample size to 4,984 participants.

Baseline Characteristics

Self-reported questionnaires completed by participants or their primary caregivers allowed collection of self-reported sociodemographic characteristics including age, race, sex, physical activity levels, smoking status, and co-morbid conditions. Age was stratified into three categories as performed in our previous analyses (60-69.9, 70-79.9, 80+ years)[15, 16] and race/ethnicity was reported as non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, and Mexican American. Co-morbid conditions were self-reported using the question, “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you have [specified medical condition]?” Smoking status was classified as “current smoker,” “former smoker,” or “never smoker.” Physical activity was categorized as sitting, walking, performing light loads or heavy work using the question, “Please tell me which of these four sentences best describes your usual daily activities?”.

Anthropometric Measures

Weight was assessed both using a self-reported questionnaire and using objective measurements. NHANES contained questions posed to persons aged 16 years and older about their current self-reported weight, their weight one year ago, 10 years ago, and weight at age 25. Additional questions included: “During the past 12 months, have you tried to lose weight?” and “During the past 12 months have you done anything to keep from gaining weight?” Height was measured using a stadiometer after deep inhalation. A tape measure was used to measure waist circumference at the iliac crest along the mid-axillary line. Measurements were performed on the right side of the body, and to the nearest tenth of a centimeter. Weight was measured using an electronic digital scale (calibrated in kilograms)

Body Composition Analysis

A dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) was used to perform all muscle and fat measurements in the analytical cohort (QDR-4500, Hologic Scanner, Bedford, MA). Specific variables that were assessed included total skeletal muscle mass, appendicular lean mass (ALM), and total body fat. The DXA scan had limits on height (maximum 192.5cm) and weight (136.4kg); additionally, individuals with metal objects in their bodies were prohibited from having their body composition measured via DXA scan as metal is contraindicated for this procedure. We defined ALM as the sum of muscle mass of all four upper/lower extremity limbs. For this analysis, we used the FNIH definitions of LLM consisting of ALM normalized for body mass index (BMI) to account for body size and adiposity [2]. Men were classified as having LLM if ALM<0.789 and women <0.512 [2]. FNIH also categorizes individuals at risk with an ALM <19.75kg in males, or <15.02 in females.

Statistical Analysis

All data were downloaded in September 2015 into a single dataset. Weight history data were integrated in November 2017 following NHANES standard operating procedures, accounting for weighting, strata, primary sampling unit, and cluster. Descriptive statistics are presented as means ± standard errors and counts (weighted percentages). Comparisons between groups (presence vs. absence of LLM) were conducted using t-tests and chi-square tests of independence. We calculated self-reported percent weight change as the quotient of the difference between baseline year and the year in question (1 year ago, 10 years ago or at age 25 years). As significant weight loss/gain is categorized as ±5%[17, 18], we created three categories: ≥5% weight loss; ≥5% weight gain; or no change in weight (−5 to +5% weight change). The latter category is represented as the referent in our models. We calculated the slope for each individual change in weight as the participant’s age at each of the three time points differed (quotient of Δ Weight Time1.- Weight Time2 and Δ Age) and is represented as the change in weight per year. Multiple models were constructed to evaluate the effect of weight change (primary predictor − gain/loss of 5%) on the risk of FNIH defined LLM using the ALM:BMI definition (primary outcome). We constructed incremental models adjusting for co-variates: age, gender (Model 1); Model 1 co-variates, race, education, smoking (Model 2); Model 2 co-variates, diabetes, arthritis, coronary artery disease, and cancer (Model 3). Logistic regression models integrating each slope on LLM are also presented. Visual representation of change in weight overtime was plotted with a LOESS local regression line[19] (span = 0.7). To account for central obesity, we adjusted our final models with waist circumference as an exploratory analysis. As muscle mass varies by sex, we also conducted stratified analyses and explored out key outcome models of the presence of ALM:BMI defined LLM stratified by BMI. Sensitivity analyses evaluated the ALM definitions. All analyses were conducted using STATA v.15 (College Station, Texas) and R v3.5. P-values were considered statistically significant if they were less than the criterion alpha level of .05.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. The rate of LLM in this cohort using the FNIH ALM:BMI definition was 23.0% with a lower rate of females fulfilling criteria for LLM (19.3 vs. 27.8%). Rates of LLM increased with age. Body mass index was significantly higher (30.4±0.20 vs. 27.6±0.20 kg/m2;p<0.001) in individuals with LLM. Table 2 outlines the self-reported weight, weight changes (in percent), and the degree of weight change (±5% weight gain/loss) during the life-cycle. There were no differences in a desire to either gain or lose weight (both scores p>0.05). Individuals with ALM-BMI defined LLM gained significantly more weight as compared to age 25 years. Categorizing weight change as significant (≥5%) loss or gain, individuals with ALM:BMI defined LLM had more weight gain at each time point and less weight loss.

Table #1:

Baseline Characteristics of Cohort

| Low Lean Mass (ALM:BMI) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall* | Overall Cohort+* | Men | Females | |||||||

| N=4,984 | N=2,453 | N=2,531 | ||||||||

| Present | Absent | P-value | Present | Absent | P-value | Present | Absent | P-value | ||

| Number | 4,984 | 1,296 (23.0) | 3,378 (77.0) | --- | 719 (27.8) | 1,576 (72.2) | --- | 577 (19.3) | 1,802 (80.7) | --- |

| Age, years | 71.1±0.19 | 72.7±0.27 | 70.3±0.21 | <0.001 | 72.1±0.34 | 69.5±0.18 | <0.001 | 73.4±0.40 | 70.8±0.25 | <0.001 |

| 60-69.9 years | 2,176 (46.6) | 466 (17.3) | 1,641 (82.7) | 239 (20.9) | 782 (79.1) | 227 (14.1) | 859 (85.9) | |||

| 70-79.9 years | 1,635 (35.2) | 465 (26.3) | 1,068 (73.7) | 282 (32.4) | 527 (67.6) | 183 (21.6) | 541 (78.4) | |||

| 80+ years | 1,173 (18.2) | 365 (32.5) | 669 (67.5) | 198 (41.9) | 267 (58.1) | 167 (27.2) | 402 (72.8) | |||

| Female sex | 2,531 (56.5) | 577 (47.2) | 1,802 (59.2) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Body Mass Index, kg/m2 | 28.2±0.10 | 30.4±0.20 | 27.6±0.12 | <0.001 | 29.9±0.28 | 27.5±0.13 | <0.001 | 30.9±0.26 | 27.7±0.16 | <0.001 |

| Fat Mass, % | 37.2±0.11 | 40.1±0.26 | 34.3±0.14 | <0.001 | 34.7±0.26 | 29.4±0.14 | <0.001 | 46.1±0.17 | 41.0±0.17 | <0.001 |

| Lean Mass, % | 60.4±.11 | 57.6±2.5 | 61.3±0.13 | <0.001 | 62.8±0.25 | 67.9±0.13 | <0.001 | 57.8±0.17 | 56.7±0.14 | <0.001 |

| ALM, kg | 19.7±0.09 | 18.4±0.19 | 20.1±0.10 | <0.001 | 25.1±0.10 | 21.7±0.21 | <0.001 | 14.7±0.13 | 16.7±0.09 | <0.001 |

| Waist Circumference, cm | 100.1±0.22 | 104.9±0.57 | 98.6±0.28 | <0.001 | 108.5±0.75 | 102.9±0.37 | <0.001 | 100.9±0.72 | 95.6±0.35 | <0.001 |

| >12 years education | 1,676 (40.6) | 342 (33.6) | 1,258 (43.5) | <0.001 | 204 (36.6) | 634 (50.6) | <0.001 | 138 (30.3) | 624 (38.5) | 0.007 |

| Race | ||||||||||

| Mexican American | 1,202 (7.3) | 521 (12.9) | 605 (5.3) | 258 (11.7) | 287 (4.6) | 263 (14.3) | 318 (5.7) | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 2,846 (81.2) | 685 (81.9) | 1990 (80.2) | <0.001 | 404 (80.7) | 932 (83.7) | <0.001 | 281 (79.6) | 1,058 (80.7) | <0.001 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 811 (8.3) | 56 (9.8) | 697 (2.7) | 35 (2.7) | 321 (9.3) | 21 (2.7) | 376 (10.2) | |||

| Co-Morbidities | ||||||||||

| Hypertension | 2,683 (53.4) | 720 (58.8) | 1,792 (51.4) | 0.004 | 378 (54.5) | 768 (47.6) | 0.02 | 342 (63.6) | 1,024 (54.1) | 0.01 |

| CHF | 373 (7.1) | 120 (9.4) | 214 (6.1) | 0.006 | 74 (10.2) | 102 (6.4) | 0.05 | 46 (8.6) | 112 (5.8) | 0.07 |

| CAD | 870 (18.3) | 269 (25.3) | 528 (15.9) | <0.001 | 164 (27.7) | 309 (20.6) | 0.03 | 105 (22.7) | 219 (12.6) | <0.001 |

| Cancer | 916 (21.7) | 208 (19.6) | 650 (22.1) | 0.10 | 129 (22.2) | 342 (25.3) | 0.13 | 79 (16.6) | 308 (19.9) | 0.09 |

| Stroke | 405 (7.6) | 134 (9.3) | 232 (6.1) | 0.02 | 75 (9.2) | 109 (5.7) | 0.03 | 118 (9.4) | 44 (6.4) | 0.11 |

| COPD | 496 (11.8) | 156 (14.8) | 314 (11.1) | 0.03 | 86 (14.9) | 114 (7.5) | <0.002 | 200 (14.6) | 70 (13.5) | 0.66 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 1,060 (29.9) | 320 (22.5) | 658 (16.9) | <0.001 | 181 (23.7) | 312 (17.6) | 0.02 | 139 (21.2) | 346 (16.4) | 0.03 |

| Arthritis | 2,379 (50.2) | 644 (52.7) | 1,583 (49.2) | 0.19 | 313 (44.1) | 594 (40.0) | 0.23 | 331 (62.4) | 989 (55.4) | 0.03 |

| Smoking | ||||||||||

| Current | 611 (11.9) | 142 (10.6) | 425 (12.2) | 103 (14.5) | 244 (13.8) | 27 (6.2) | 181 (11.0) | |||

| Former | 2,035 (41.4) | 553 (43.1) | 1,364 (40.9) | 0.31 | 396 (56.4) | 815 (55.2) | 0.82 | 78 (28.3) | 549 (31.0) | 0.002 |

| Never | 2,327 (46.7) | 600 (46.3) | 1,583 (46.9) | 220 (29.1) | 513 (31.0) | 51 (65.5) | 1,070 (57.9) | |||

| Physical Activity | ||||||||||

| Sits | 1,569 (29.3) | 455 (34.2) | 927 (25.7) | 242 (32.8) | 427 (24.6) | 213 (35.7) | 500 (26.4) | |||

| Walks | 2,756 (55.6) | 699 (51.9) | 1,954 (58.4) | 378 (50.0) | 882 (54.0) | 321 (54.0) | 1,072 (60.0) | |||

| Light loads | 541 (13.1) | 118 (12.2) | 408 (13.9) | 0.005 | 80 (14.1) | 203 (15.7) | 0.06 | 38 (10.0) | 205 (12.6) | 0.03 |

| Heavy work | 106 (2.0 | 22 (1.8) | 80 (2.1) | 18 (3.0) | 59 (3.6) | 4 (0.4) | 21 (1.0) | |||

All values represent means ± standard errors or counts (weighted percentages)

Abbreviation: ALM – appendicular lean mass; CAD – coronary artery disease; CHF – congestive heart failure; COPD – chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

n=310 missing values without complete data

Table 2:

Weight Change and Rates of Low Lean Mass (ALM:BMI)

| Overall Cohort | Men | Females | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Lean Mass | Low Lean Mass | Low Lean Mass | ||||||||

| Overall | Present | Absent | P-value | Present | Absent | P-value | Present | Absent | P-value | |

| Prevalence, % | --- | 1,296 (23.0) | 3,378 (77.0) | --- | ||||||

| Self-Reported Weight Status | 84.5±0.89 | 86.3±0.47 | 0.09 | 71.3±0.72 | 71.0±0.41 | 0.69 | ||||

| Current Weight, kg | 77.4±0.31 | 78.3±0.66 | 77.3±0.36 | 0.20 | 85.2±0.89 | 87.0±0.51 | 0.10 | 71.2±0.76 | 71.7±0.45 | 0.59 |

| One year ago, kg | 78.1±0.34 | 78.6±0.70 | 78.0±0.39 | 0.45 | 81.9±0.99 | 84.8±0.42 | 0.02 | 67.6±0.68 | 68.0±0.45 | 0.59 |

| Ten years ago, kg | 75.1±0.32 | 75.2±0.71 | 74.9±0.34 | 0.78 | 70.1±0.52 | 75.5±0.43 | <0.001 | 54.5±0.60 | 57.5±0.25 | <0.001 |

| At age 25 years, kg | 64.5±0.22 | 62.8±0.50 | 64.9±0.26 | 0.001 | ||||||

| Tried to lose weight, % | 1,164 (28.1) | 339 (31.9) | 783 (27.9) | 0.10 | 178 (29.4) | 465 (24.3) | 0.12 | 161 (34.6) | 482 (30.4) | 0.24 |

| Tried not to gain weight, % | 1,620 (37.2) | 444 (38.5) | 1113 (37.9) | 0.78 | 244 (37.2) | 486 (36.6) | 0.82 | 200 (40.0) | 627 (38.8) | 0.69 |

| Self-Reported Weight Change | ||||||||||

| 1 year to Current Weight , % | −1.0±0.13 | −0.5±0.20 | −1.1±0.15 | 0.02 | −0.92±0.31 | −0.88±0.15 | 0.92 | −0.06±0.37 | −1.3±0.27 | 0.03 |

| 10 years to Current Weight , % | +2.16±0.27 | 3.2±0.48 | 2.2±0.26 | 0.05 | 2.2±0.6 | 1.2±0.20 | 0.14 | 4.3±0.67 | 2.9±0.42 | 0.04 |

| Age 25 to Current Weight , % | 15.1±0.31 | 18.6±0.59 | 14.4±0.35 | <0.001 | 21.8±0.86 | 16.7±0.49 | <0.001 | 15.8±0.73 | 11.3±0.39 | <0.001 |

| Weight Δ: 1 year to Current Weight | 0.04±0.00 | 0.03±0.00 | ||||||||

| ≥5% weight loss | 933 (18.4) | 236 (16.3) | 626 (18.7) | 125 (15.1) | 262 (15.4) | 111 (17.7) | 364 (21.1) | |||

| No weight Δ (−5 to +5%) | 3,323 (70.0) | 837 (70.2) | 2,309 (70.5) | 0.07 | 502 (76.1) | 1158 (76.9) | 0.85 | 335 (63.5) | 1151 (66.0) | 0.01 |

| ≥5% weight gain | 584 (11.6) | 168 (13.5) | 379 (10.8) | 69 (8.7) | 137 (7.7) | 99 (18.8) | 242 (12.9) | |||

| Weight Δ: 10 years to Current Weight | ||||||||||

| ≥5% weight loss | 1,214 (21.7) | 289 (19.4) | 811 (21.2) | 171 (21.4) | 400 (19.5) | 118 (19.3) | 411 (21.1) | |||

| No weight Δ (−5 to +5%) | 1,722 (37.5) | 402 (31.7) | 1,230 (39.6) | <0.001 | 256 (37.5) | 669 (46.4) | 0.002 | 146 (25.1) | 561 (34.8) | 0.004 |

| ≥5% weight gain | 1,829 (40.9) | 527 (48.9) | 1,224 (39.1) | 262 (32.1) | 473 (43.0) | 265 (55.6) | 751 (44.1) | |||

| Weight Δ: Age 25 to Current Weight | ||||||||||

| ≥5% weight loss | 513 (9.4) | 87 (6.1) | 361 (9.6) | 55 (7.3) | 195 (10.4) | 32 (4.7) | 166 (9.1) | |||

| No weight Δ (−5 to +5%) | 638 (13.3) | 121 (8.7) | 478 (14.7) | <0.001 | 75 (10.5) | 287 (19.3) | <0.001 | 46 (6.6) | 191 (11.3) | <0.001 |

| ≤5% weight gain | 3,483 (77.4) | 973 (85.2) | 2348 (75.7) | 535 (82.2) | 1,033 (70.3) | 438 (88.6) | 1,315 (79.6) | |||

| Weight Δ: 10 years ago to One year ago | ||||||||||

| ≥5% weight loss | 844 (15.0) | 206 (14.1) | 545 (14.0) | 55 (15.3) | 287 (14.0) | 32 (12.7) | 166 (14.0) | |||

| No weight Δ (−5 to +5%) | 2,153 (45.7) | 524 (42.4) | 1,519 (47.1) | 0.10 | 75 (44.2) | 287 (53.7) | 0.02 | 46 (40.2) | 191 (42.4) | 0.57 |

| ≤5% weight gain | 1,747 (39.4) | 482 (38.9) | 1,192 (43.5) | 535 (40.5) | 1,033 (32.3) | 438 (47.1) | 1,315 (43.6) | |||

| Weight Δ: Age 25 year to One year ago | ||||||||||

| ≥5% weight loss | 441 (8.2) | 77 (5.4) | 309 (8.4) | 46 (6.2) | 175 (9.5) | 31 (4.7) | 134 (7.6) | |||

| No weight Δ (−5 to +5%) | 2,444 (52.3) | 625 (51.2) | 1,687 (52.6) | <0.001 | 376 (54.1) | 885 (58.6) | 0.03 | 249 (47.8) | 802 (48.4) | 0.03 |

| ≤5% weight gain | 1,698 (39.4) | 466 (43.3) | 1,161 (39.0) | 241 (39.7) | 442 (31.9) | 225 (47.5) | 719 (44.0) | |||

| Weight Δ: Age 25 years to 10 years ago | ||||||||||

| ≥5% weight loss | 277 (5.5) | 56 (4.4) | 197 (5.7) | 32 (4.4) | 106 (6.2) | 24 (4.4) | 91 (5.4) | |||

| No weight Δ (−5 to +5%) | 966 (19.8) | 184 (14.0) | 716 (21.3) | <0.001 | 118 (17.5) | 391 (24.4) | 0.005 | 66 (9.9) | 325 (19.1) | <0.001 |

| ≤5% weight gain | 3,373 (74.7) | 934 (81.6) | 2,263 (73.0) | 420 (85.6) | 1,248 (75.6) | 514 (78.1) | 1,015 (69.4) | |||

All values represent means ± standard errors or counts (weighted percentages)

p-values represent the differences between the presence of low lean mass (based on cutoffs of appendicular lean mass:body mass index and absence of low lean mass by weight status and time period.

ALM: appendicular lean mass; BMI: body mass index

Our multivariable models (Table 3) demonstrate that ≥5% weight gain is associated with the development of ALM:BMI-defined LLM, particularly over extended periods of time in the life-course (i.e., between baseline and 10 years, or between 1 year and age 25 years) in both sexes. Weight loss of ≥5% from Age 25 to 1 year ago had a lower odds ratio of developing LLM. Adjusting for current survey waist circumference dampened these findings (Appendix 1). We explored the change in weight trajectory by evaluating the slope between each designated time point (Table 4, Appendix 2) and observed that individuals with ALM:BMI-defined LLM had significant weight gain with increasing time (current to one year; one year to 10 years) and less weight gain in the third interval (10 years ago to age 25 years), than those without defined LLM. We did not observe differences by sex. Figure 1 represents the change in weight as a function of age with a LOESS smoothed line by LLM status, and Appendix 3 graphically depicts by sex. Graphically, stability of weight is observed among individuals without ALM:BMI-defined LLM as compared to those without. For every 1kg increase a person had in the past year, the odds of ALM:BMI defined LLM increased by 2% (OR: 1.02 95% CI: 1.01,1.04). For every 1kg/1year increase in weight change from 10 years ago to current age, the odds of LLM were increased by 14% (OR: 1.14 [1.00,1.31] ). For every 1kg/1year increase in weight change from age 25 to 10 years ago, the odds of LLM increased by 81% (OR: 1.82 [1.17,2.81]). Peak weight among individuals with ALM:BMT defined LLM was lower (79.2 vs. 80.3kg) than among those without LLM and peak weight occurred at a later age (63.7 vs. 60.7 years). Results were no different by sex (data not shown). Finally, our sensitivity analysis using the ALM definition of LLM suggested that weight loss was associated with an increased risk of LLM (Appendix 4–8), and that overweight and obesity had lesser rates of weight change than normal BMT (Table 5). We found no relationship with BMT categories and relative differences in weight-loss or gain.

Table 3:

Association of Weight Change and FNIH Low Lean Mass (ALM:BMI)

| Overall Cohort | Males | Females | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight Status | Weight Status | Weight Status | |||||||

| Time Period | No Weight Δ | ≥5% gain | ≥5% loss | No Weight Δ | ≥5% gain | ≥5% loss | No Weight Δ | ≥5% gain | ≥5% loss |

| One year ago to Current Weight | Referent | 1.35 [0.99, 1.87] | 0.89 [0.70, 1.12] | Referent | 1.10 [0.66,1.27] | 0.92 [0.66,1.27] | Referent | 1.52 [1.07,2.18] | 0.88 [0.60,1.28] |

| 10 years ago to Current Weight | Referent | 2.03 [1.66, 2.49] | 0.98 [0.76, 1.28] | Referent | 1.99 [1.51,2.63] | 0.91 [0.65,1.26] | Referent | 2.10 [1.47,3.00] | 1.06 [0.74,1.51] |

| Age 25 years to Current Weight | Referent | 2.37 [1.76, 3.20] | 0.95 [0.65, 1.39] | Referent | 2.45 [1.60,3.75] | 1.15 [0.63,2.09] | Referent | 2.21 [1.32,3.70] | 0.68 [0.36,1.30] |

| 10 years ago to 1 year ago | Referent | 1.59 [1.29, 1.96] | 0.94 [0.68, 1.29] | Referent | 1.77 [1.38,2.27] | 1.06 [0.74,1.54] | Referent | 1.40 [0.99,1.97] | 0.77 [0.51,1.19] |

| Age 25 years to 1 year ago | Referent | 1.49 [1.21, 1.85] | 0.55 [0.40, 0.75] | Referent | 1.62 [1.25,2.10] | 0.59 [0.38,0.91] | Referent | 1.37 [0.96,1.95] | 0.46 [0.26,0.82] |

| Age 25 years to 10 year ago | Referent | 1.83 [1.47, 2.30] | 1.03 [0.62, 1.69] | Referent | 1.53 [1.10,2.14] | 0.89 [0.46,1.74] | Referent | 2.35 [1.51,3.66] | 1.30 [0.65,2.59] |

Multivariable logistic regression models (referent category: no change in weight) are represented as odds ratios (95% confidence intervals). The primary predictor was weight change (gain ≥5%, loss of 5%, or no change in weight [referent]) during the time period. Separate multivariable models were created for the outcomes of low lean mass (yes/no). The presence of low lean mass was defined using the Foundation of the National Institute of Health Sarcopenia guidelines (appendicular lean mass [ALM]:body mass index [BMI]<0.789 in men; <0.512 in women)[2]. Models presented were adjusted for: age, sex, race, education status, smoking status, self-reported diabetes, arthritis, coronary artery disease, cancer for the overall cohort. Models for Males and Females are not adjusted for sex.

FNIH – Foundation for the National Institute of Health

Table 4:

Rate of Weight Change Year Over 3 Timespans Slopes and Risk of Low Lean Mass (ALM:BMI)

| Slope of Weight Δ per unit time | Model 1 | p-value | Model 2 | p-value | Model 3 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 year ago to current | 1.02 | 0.002 | 1.02 | 0.004 | 1.02 | 0.004 |

| 10 years ago to current | 1.09 | 0.049 | 1.12 | 0.013 | 1.14 | 0.004 |

| Age 25 to 10 years ago | 1.67 | <0.001 | 1.79 | <0.001 | 1.64 | 0.001 |

| Male Gender | 0.61 | <0.001 | 0.55 | <0.001 | 0.55 | <0.001 |

| Race | --- | --- | ||||

| Mexican American | --- | --- | Referent | --- | Referent | Referent |

| Non-Hispanic White | --- | --- | 0.40 | <0.001 | 0.38 | <0.001 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | --- | --- | 0.09 | <0.001 | 0.09 | <0.001 |

| Other | --- | --- | 0.68 | 0.142 | 0.68 | 0.152 |

| Education: >12 years | --- | --- | 0.62 | <0.001 | 0.64 | <0.001 |

| Smoking Status | --- | --- | ||||

| Never | --- | --- | Referent | --- | Referent | --- |

| Former | --- | --- | 0.91 | 0.352 | 0.87 | 0.196 |

| Current | --- | --- | 0.79 | 0.083 | 0.77 | 0.062 |

| Diabetes | --- | --- | --- | --- | 1.18 | 0.107 |

| Arthritis | --- | --- | --- | --- | 1.25 | 0.050 |

| Coronary Artery Disease | --- | --- | --- | --- | 1.74 | <0.001 |

| Cancer | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.88 | 0.188 |

| Constant | --- | --- | 1.02 | 0.905 | 0.88 | 0.425 |

Multivariable models listed above are represented as odds ratios [95% confidence intervals]. Each model is represented vertically with co-variates. Model 1: age, gender; Model 2: age, gender co-variates, race, education, smoking; Model 2 co-variates, diabetes, arthritis, coronary artery disease, and cancer. The presence of low lean mass was defined using the Foundation of the National Institute of Health Sarcopenia guidelines (appendicular lean mass [ALM]:body mass index [BMI]<0.789 in men; <0.512 in women)[2].

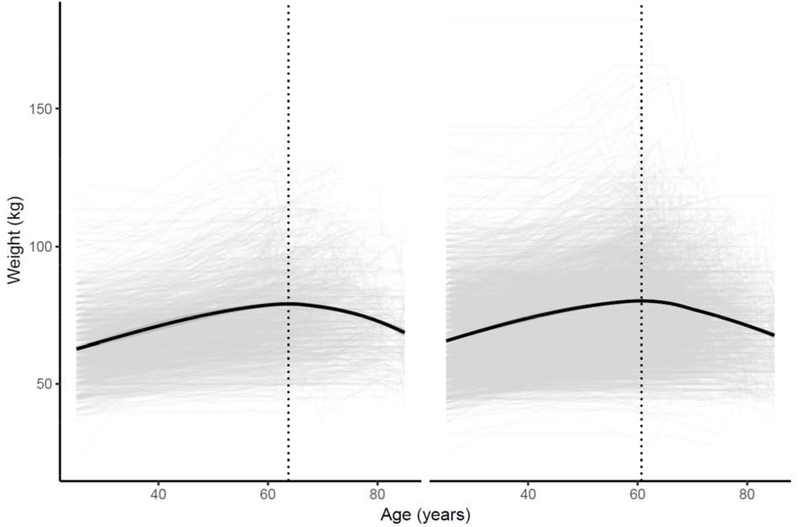

Figure 1: Change in Weight by Low Lean Mass Status (Appendicular Lean Mass:BMI).

The figure represents a LOESS model plot that demonstrates changes in weight status (in kilograms) by age status. Panel (a) represents trajectory of participants fulfilling Low Lean Mass Criteria (appendicular lean mass [ALM]:body mass index [BMI]<0.789 in men; <0.512 in women)[2]), while panel (b) represents participants that do not fulfill the criteria.

Title: Weight as a Person Ages by Low Lean Mass Status (Appendicular Lean Mass:BMI)

All values represent means ± standard errors or counts (weighted percentages)

p-values represent the differences between the presence of low lean mass and absence of low lean mass by weight status and time period.

BMI: body mass index

Table 5:

Results Stratified by Body Mass Index Category

| BMI 18.5-24.9kg | BMI 25.0-29.9 kg/m2 | BMI ≥30kg/m2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time Period | No Weight Δ | ≥5% gain | ≥5% loss | No Weight Δ | ≥5% gain | ≥5% loss | No Weight Δ | ≥5% gain | ≥5% loss |

| One year ago to Current Weight | Referent | 0.82 [0.19,3.44] | 0.77 [0.45,1.31] | Referent | 1.09 [0.66,1.82] | 0.86 [0.58,1.28] | Referent | 1.08=7 [0.66,1.75] | 1.14 [0.82,1.60] |

| 10 years ago to Current Weight | Referent | 1.47 [0.78,2.76] | 0.72 [0.44,1.19] | Referent | 1.59 [1.12,2.27] | 1.37 [0.89,2.11] | Referent | 1.50 [0.90,2.49] | 1.31 [0.94,1.83] |

| Age 25 years to Current Weight | Referent | 2.11 [1.16,3.81] | 1.18 [0.67,2.09] | Referent | 1.00 [0.63,1.57] | 1.05 [0.50,2.19] | Referent | 1.76 [0.66,4.73] | 1.30 [0.34,5.06] |

| 10 years ago to 1 year ago | Referent | 1.47 [0.84,2.58] | 0.91 [0.56,1.49] | Referent | 1.15 [0.85,1.55] | 1.15 [0.73,1.83] | Referent | 1.03 [0.71,1.49] | 1.79 [0.88,3.63] |

| Age 25 years to 1 year ago | Referent | 1.47 [0.82,2.64] | 0.79 [0.49,1.26] | Referent | 1.06 [0.78,1.44] | 0.97 [0.53,1.79] | Referent | 0.91 [0.65,1.26] | 0.71 [0.22,2.29] |

| Age 25 years to 10 year ago | Referent | 1.60 [0.98,2.61] | 1.13 [0.60,2.13] | Referent | 1.25 [0.88,1.76] | 1.39 [0.55,3.46] | Referent | 1.22 [0.73,2.04] | 1.21 [0.38,3.88] |

| Slope of Weight Change | |||||||||

| BMI 18.5-24.9kg | BMI 25.0-29.9 kg/m2 | BMI ≥30kg/m2 | |||||||

| Model 3 | p-value | Model 3 | p-value | Model 3 | p-value | ||||

| 1 year ago to current | 1.00 | 0.80 | 0.99 | 0.37 | 0.99 | 0.37 | |||

| 10 years ago to current | 1.18 | 0.30 | 0.78 | 0.009 | 0.78 | 0.009 | |||

| Age 25 to 10 years ago | 0.86 | 0.67 | 0.38 | 0.001 | 0.38 | 0.001 | |||

DISCUSSION

Our results highlight the importance of establishing a self-reported weight history in older adults. Weight change may provide early evidence of risk of important geriatric syndromes such as low lean mass. A simple, cost-effective, clinical measure that is routinely measured in practice, weight change may provide early evidence in tracking such trajectories.

To our knowledge, we are unaware of studies evaluating the impact of weight changes and the risk of LLM. Newman evaluated the impact of 4-year weight changes in 70-79 year olds using Health, Aging, and Body Composition Data[20]. These authors demonstrated that weight loss was strongly associated with muscle mass loss in both sexes, even with weight regain. Among female participants, loss of weight of more than 5% in those aged 75 years and older was independently associated with disability risk[21]. The impact of obesity using BMI on the lifetime impact of physical function has been well characterized [22–25], particularly in mid-life [26]. Weight change is important and normal during the life cycle. Individuals at higher risk are those with suboptimal weight gain, as compared to population norms. Additionally, our results suggest that weight change accounting for obesity (i.e., BMI) is strongly predictive of the development of LLM. Weight change is important in a number of chronic diseases that can predispose to falls[27, 28], fractures[29, 30] and institutionalization[31]. Weight cycling places individuals at higher risk of functional impairment and mortality, two constructs that were not assesed by this study. Weight cycling is strongly associated with an increased number of ADL limitations using Cardiovascular Heart Study Data, and frequent weight cycling in a Finnish study was associated with poorer health[32] and increased risk of disability[33, 34].

The current findings provide information to both support and refute paradigms of weight management for older adults. First, weight gain, particularly over the long-term, increases the risk of ALM:BMI-defined LLM. In fact, the risk is highest between weight at age 25 and current weight (OR 2.37 [1.76,3.20]). Weight gain may be a harbinger of functional decline and incident frailty, suggesting the need for clinicians to pay closer attention to this phenomenon. Evidence-based interventions to augment nutrition and physical activity levels may counter the risk of developing functional impairment[35]. Without objective life-course changes in muscle mass or strength, it is impossible to determine whether weight change was due predominantly to loss of muscle or fat. Second, our findings indicate that weight gain of ≥5% is strongly associated with the development of LLM. A number of reasons may account for this finding. Individuals with obesity tend to have higher levels of ALM to support their weight. Further, we used specific thresholds for LLM; individuals on the cusp may not necessarily be classified as having sarcopenia. Lastly, we were unable to ascertain whether weight changes were voluntary or involuntary using this dataset, and hence cannot comment on the long-term impact of weight-loss interventions.

Weight gain often occurs centrally, which may contribute to sarcopenic obesity through pro-inflammatory cytokines and muscle mass infiltration by fat[36]. In further modeling, we adjusted for waist circumference which dampened this relationship. Weight gain is generally associated with mortality, particularly if it is excessive[37, 38]. The exception to this is in old age, where a modest weight gain might be protective among those not already overweight or obese[39]. We continue to endorse the importance of weight loss among older adults meeting established criteria. Future research should further evaluate this relationship.

As with any epidemiological study there are inherent limitations of the study’s design. First, we relied fully on self-reported weight for these analyses. Previous studies have demonstrated discrepancies between objective and self-reported weight measurements within this dataset[40]; however, self-reported weight is more easily obtained from patients in clinical practice that may not have longitudinal access to records. Second, NHANES is unable to capture non-institutionalized adults who may be at higher risk of developing LLM. Third, we did not evaluate muscle strength, which is an integral component of the FNIH definitions. NHANES assesses knee extensor strength which is not practically evaluated clinically, and assesses grip strength in different cycles than that of body composition. We also recognize the inherent differences between FNIH[2] and European Working Group for the Study of Sarcopenia guidelines[41]. Fourth, while our counts differ with adding co-variates, our estimates did not change significantly.

Last, we previously suggested that the FNIH definition of ALM normalized for BMI should be used over ALM-only[15], and our results strongly support this statement. Interestingly, conflicting relationships were observed dependent on the sarcopenia definition as demonstrated not only in our earlier work[16, 42], but by others as well[43–45]. The variables we incorporated in our models[46], or the inability to accurately ascertain muscle mass due to hydration or intramuscular fat deposition may impact our findings. We strongly believe that harmonizing definitions is a major priority in the future based on reference populations with different body mass. Last, as we are using linear models for interpretation we do not suggest that the true relationship between weight change and odds of sarcopenia is linear. We also acknowledge that we have not accounted for competing mortality, disability, or acute hospitalization risks in this analysis. In fact, opporsite findings were observed using ALM as the criteria. This is not surprising as ALM:BMI may be more suitable for capturing LLM in overweight and obese individuals. Further, any incremental increase in body fat may lead to a 25% incremental increase in lean mass{Heymsfield, 2014 #456}, thus exceeding the thresholds for sarcopenia. Our exploratory analysis evaluating whether differences were observed by BMI category suggest that the odds of developing LLM may be related to obesity; however, we note that the BMI categories were assessed only at one timepoint (ie: follow-up) and cannot account for changes in BMI trajectories over the lifespan.

Implications

With the implementation of electronic medical records, clinicians have a wealth of information (i.e., weight status) that could be manipulated easily and quickly at the point of care. Informatics teams could easily create algorithms that determine changes in weight over time, which in turn could be used in population-based predictive analytics to identify individuals at risk for reduced physical function. Using weight and BMI over DXA-based body composition measures allows for population health-based management that can easily be disseminated in resource poor areas across the United States. Further, weight is well accepted by most clinicians and well understood, over and above other anthropometric measures or functional measures such as grip strength.

CONCLUSIONS

Weight change over a life-course can be clinically helpful in predicting the risk of LLM.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURES:

This work is supported by the following agencies:

Dr. Batsis receives funding from the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23AG051681. Dr. Batsis has consulted for the Royal College of Physicians of Ireland and Dinse, Knapp, McAndrew LLC, legal firm.

Dr. Mackenzie: none

Lillian Seo receives funding from the Geisel School of Medicine Office of Financial Aid for Medical Student Summer Research.

Support was also provided by the Dartmouth Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Research Center supported by Cooperative Agreement Number U48DP005018 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Dartmouth Clinical and Translational Science Institute, under award number UL1TR001086 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Preparation of this manuscript was also supported in part by the National Institute of Mental Health (T32 MH073553, PI: Bartels, Fellow: Stevens; T32MH020031).

The findings and conclusions in this journal article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the National Insitutes of Health. The authors acknowledge Friends of the Norris Cotton Cancer Center at Dartmouth and National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant 5P30 CA023108-37 Developmental Funds

ABBREVIATIONS

- ALM

appendicular lean mass

- BMI

body mass index

- DXA

Dual energy x-ray absorptiometry

- FNIH

Foundation for the National Institutes of Health

- LLM

Low lean mass

- NHANES

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

Appendix 1: Association of Weight Change and FNIH Low Lean Mass (ALM:BMI) Adjusting for Waist Circumference

| Low Lean Mass:BMI | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Weight Status | |||

| Time Period | No Weight Δ | ≥5% gain | ≥5% loss |

| One year ago to Current Weight | Referent | 1.19 [0.85,1.66] | 0.92 [0.73,1.16] |

| 10 years ago to Current Weight | Referent | 1.57 [1.27,1.94] | 1.15 [0.87,1.51] |

| Age 25 years to Current Weight | Referent | 1.62 [1.17,,2.24] | 1.08 [0.71,1.64] |

| 10 years ago to 1 year ago | Referent | 1.23 [0.97,1.55] | 1.17 [0.83,1.67] |

| Age 25 years to 1 year ago | Referent | 1.12 [0.89,1.41] | 0.75 [0.53,1.07] |

| Age 25 years to 10 years ago | Referent | 1.41 [1.12,1.78] | 1.13 [0.68,1.88] |

Multivariable logistic regression models (referent category: no change in weight) are represented as odds ratios (95% confidence intervals). The primary predictor was weight change (gain ≥5%, loss of 5%, or no change in weight) during the time period. Separate multivariable models were created for the outcomes of low lean mass (yes/no). The presence of low lean mass was defined using the Foundation of the National Institute of Health Sarcopenia guidelines (ALM<0.789 in men; <0.512 in women)[2]. Models presented were adjusted for: age, sex, race, education status, smoking status, self-reported diabetes, arthritis, coronary artery disease, cancer, and waist circumference.

Appendix 2: Slope of Weight Change over the Life-course and Risk of Low Lean Mass (Appendicular Lean Mass:BMI)

| Slope of Weight per unit time | One year ago to Current Weight | p-value | 10 years ago to 1 year | p-value | Age 25 years to 10 years ago | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Both Sexes | Overall | −0.626±0.102 | --- | 0.336±0.023 | --- | 0.312±0.008 | --- |

| Slope | 0.434±0.207 | 0.04 | 0.0366±0.044 | 0.41 | 0.053±0.016 | 0.001 | |

| Constant | −0.695 | 0.343±0.023 | 0.302±0.009 | ||||

| ALM:BMI − | −0.695±0.117 | 0.343±0.023 | 0.302±0.0093 | ||||

| ALM:BMI + | −0.261±0.199 | 0.379±0.044 | 0.356±0.013 | ||||

| Females | Slope | 0.827±0.316 | 0.012 | 0.0026±0.052 | 0.96 | 0.0464±0.019 | 0.02 |

| Constant | −0.713±0.196 | 0.403±0.033 | 0.316 | ||||

| ALM:BMI − | −0.713±0.196 | 0.402±0.033 | 0.316±0.011 | ||||

| ALM:BMI + | 0.113±0.308 | 0.405±0.054 | 0.363±0.015 | ||||

| Males | Slope | 0.0764±0.296 | 0.80 | 0.099±0.061 | 0.11 | 0.0667±0.025 | 0.01 |

| Constant | −0.669 | 0.258 | 0.283 | ||||

| ALM:BMI − | −0.67±0.14 | 0.258±0.026 | 0.283±0.012 | ||||

| ALM:BMI + | −0592±0.278 | 0.357±0.057 | 0.350±0.023 | ||||

Changes in slope of weight were determined as the quotient of Δ weight (Time2 − Time1) and Δ in age at the two time points. Slopes are presented for the overall cohort and by Low Lean Mass Status at Follow-up.

ALM: Appendicular lean mass; BMI: body mass index

Low lean mass was defined using the Foundation of the National Institute of Health Sarcopenia guidelines (ALM:BMI<0.789 in males; <0.512 in females).

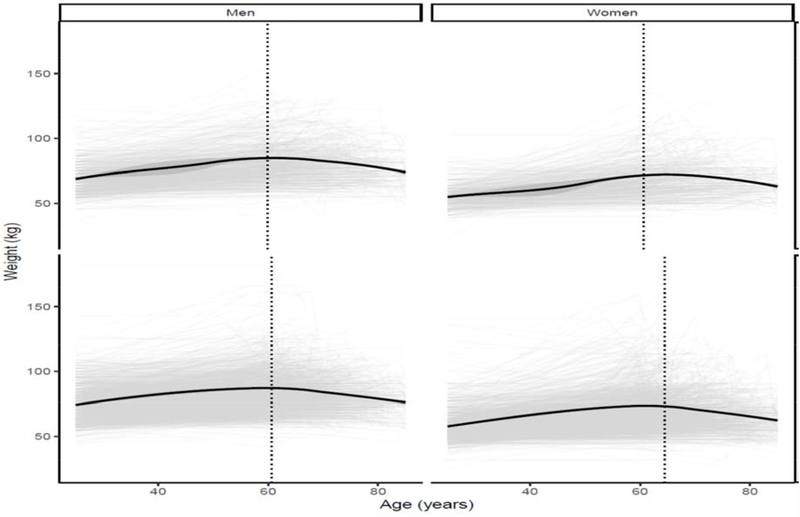

Appendix 3: Change in Weight by Low Lean Mass Status (Appendicular Lean Mass:BMI) by sex

The figure represents a LOESS model plot that demonstrates changes in weight status (in kilograms) by age status. Panel (a) represents males: i) trajectory of participants fulfilling Low Lean Mass Criteria (ALM<0.789); ii) represents participants that do not fulfill the criteria. Panel (b) represents females: i) trajectory of participants fulfilling Low Lean Mass Criteria

(ALM<0.512); ii) represents participants that do not fulfill the criteria

Appendix 4: Weight Change and Rates of Low Lean Mass

| Low lean mass | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Present | Absent | ||

| Prevalence, % | --- | 1,487 (29.9) | 3,305 (70.1) | --- |

| Self-Reported Weight Status | ||||

| Current Weight, kg | 77.4±0.31 | 61.2±0.29 | 84.4±0.30 | <0.001 |

| One year ago, kg | 78.1±0.34 | 62.1±0.31 | 84.9±0.34 | <0.001 |

| Ten years ago, kg | 75.1±0.32 | 62.2±0.32 | 80.5±0.33 | <0.001 |

| At age 25 years, kg | 64.5±0.22 | 56.3±0.34 | 67.9±0.27 | <0.001 |

| Mean Age from Age 25 years | 46.1±0.19 | 48.7±0.28 | 44.8±0.19 | <0.001 |

| Tried to lose weight, % | 1,164 (28.1) | 213 (16.2) | 932 (33.9) | <0.001 |

| Tried not to gain weight, % | 1,620 (37.2) | 307 (24.9) | 1,277 (43.0) | <0.001 |

| Self-Reported Weight Change | ||||

| 1 year to Current Weight , % | −1.0±0.13 | −1.76±0.25 | −0.65±0.17 | <0.001 |

| 10 years to Current Weight , % | +2.16±0.27 | −2.26±0.51 | 4.12±0.32 | <0.001 |

| Age 25 to Current Weight , % | 15.1±0.31 | 7.08±0.63 | 18.6±0.31 | <0.001 |

| Weight Δ: 1 year to Current Weight | ||||

| ≥5% weight loss | 933 (18.4) | 312 (20.3) | 582 (17.5) | |

| No weight Δ (−5 to +5%) | 3,323 (70.0) | 1,004 (70.9) | 2,211 (69.9) | 0.02 |

| ≥5% weight gain | 584 (11.6) | 132 (8.8) | 428 (12.6) | |

| Weight Δ: 10 years to Current Weight | ||||

| ≥5% weight loss | 1,214 (21.7) | 565 (32.3) | 1,099 (16.9) | |

| No weight Δ (−5 to +5%) | 1,722 (37.5) | 494 (40.4) | 661 (36.3) | <0.001 |

| ≥5% weight gain | 1,829 (40.9) | 350 (27.3) | 1,424 (46.8) | |

| Weight Δ: Age 25 to Current Weight | ||||

| ≥5% weight loss | 513 (9.4) | 271 (19.0) | 206 (5.1) | |

| No weight Δ (−5 to +5%) | 638 (13.3) | 292 (21.1) | 325 (10.1) | <0.001 |

| ≤5% weight gain | 3,483 (77.4) | 786 (59.9) | 2,589 (84.8) | |

| Weight Δ: 10 years ago to One year ago | ||||

| ≥5% weight loss | 844 (15.0) | 364 (24.0) | 430 (10.7) | |

| No weight Δ (−5 to +5%) | 2,153 (45.7) | 716 (50.9) | 1,370 (43.5) | <0.001 |

| ≤5% weight gain | 1,747 (39.4) | 326 (25.1) | 1,373 (45.8) | |

| Weight Δ: Age 25 year to One year ago | ||||

| ≥5% weight loss | 441 (8.2) | 230 (16.3) | 180 (4.6) | |

| No weight Δ (−5 to +5%) | 2,444 (52.3) | 803 (59.6) | 1,560 (49.3) | <0.001 |

| ≤5% weight gain | 1,698 (39.4) | 296 (24.0) | 1,356 (46.1) | |

| Weight Δ: Age 25 years to 10 years ago | ||||

| ≥5% weight loss | 277 (5.5) | 139 (10.3) | 125 (3.5) | |

| No weight Δ (−5 to +5%) | 966 (19.8) | 382 (27.7) | 544 (16.4) | <0.001 |

| ≤5% weight gain | 3,373 (74.7) | 822 (61.9) | 2,438 (80.1) | |

All values represent means ± standard errors or counts (weighted percentages)

p-values represent the differences between the presence of low lean mass and absence of low lean mass (defined by ALM) by weight status and time period.

Appendix 5: Association of Weight Change and FNIH Low Lean Mass

| Weight Status | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Time Period | No Weight Δ | ≥5% gain | ≥5% loss |

| One year ago to Current Weight | Referent | 0.57 [0.40,0.82] | 1.06 [0.85,1.31] |

| 10 years ago to Current Weight | Referent | 0.46 [0.37,0.56] | 1.59 [1.23,2.07] |

| Age 25 years to Current Weight | Referent | 0.27 [0.20,0.36] | 1.61 [1.13,2.30] |

| 10 years ago to 1 year ago | Referent | 0.44 [0.38,0.52] | 1.92 [1.46,2.53] |

| Age 25 years to 1 year ago | Referent | 0.39 [0.32,0.47] | 2.95 [2.11,4.12] |

| Age 25 years to 1 year ago | Referent | 0.43 [0.33,0.55] | 1.86 [1.14,3.01] |

Multivariable logistic regression models (referent category: no change in weight) are represented as odds ratios (95% confidence intervals). The primary predictor was weight change (gain ≥5%, loss of 5%, or no change in weight [referent]) during the time period. Separate multivariable models were created for the outcomes of low lean mass (yes/no). The presence of low lean mass was defined using the Foundation of the National Institute of Health Sarcopenia guidelines (ALM<19.75kg in men; <15.02kg in women)[2]. Models presented were adjusted for: age, sex, race, education status, smoking status, self-reported diabetes, arthritis, coronary artery disease, cancer.

FNIH – Foundation for the National Institute of Health

ALM – appendicular lean mass

Appendix 6. Rate of Weight Change per Year Over 3 Timespans Slopes and Risk of Low Lean Mass (ALM)

| Slope of Weight Δ per unit time | Model 1 | p-value | Model 2 | p-value | Model 3 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 year ago to current | 0.93 [0.91,0.94] | <0.001 | 0.92 [0.91,0.94] | <0.001 | 0.92 [0.91,0.94] | <0.001 |

| 10 years ago to current | 0.38 [0.33,0.45] | <0.001 | 0.37 [0.31,0.44] | <0.001 | 0.37 [0.31,0.44] | <0.001 |

| Age 25 to 10 years ago | 0.038 [0.024,0.062] | <0.001 | 0.04 [0.02,0.06] | <0.001 | 0.04 [0.03,0.07] | <0.001 |

| Male Gender | 6.25 [4.90,7.98] | <0.001 | 6.47 [4.91,8.54] | <0.001 | 6.50 [4.92,8.59] | <0.001 |

| Race | --- | --- | ||||

| Mexican American | --- | --- | Referent | --- | Referent | Referent |

| Non-Hispanic White | --- | --- | 0.51 [0.37,0.70] | <0.001 | 0.49 [0.36,0.67] | <0.001 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | --- | --- | 0.10 [0.06,0.15] | <0.001 | 0.10 [0.07,0.16] | <0.001 |

| Other | --- | --- | 1.20 [0.69,2.09] | 0.51 | 1.23 [0.70,2.14] | 0.46 |

| Education: >12 years | --- | --- | 0.68 [0.56,0.83] | <0.001 | 0.66 [0.54,0.82] | <0.001 |

| Smoking Status | --- | --- | ||||

| Never | --- | --- | Referent | --- | Referent | --- |

| Former | --- | --- | 1.03 [0.78,1.36] | 0.82 | 1.04 [0.80,1.36] | 0.76 |

| Current | --- | --- | 1.62 [1.18,2.23] | 0.04 | 1.65 [1.19,2.28] | 0.003 |

| Diabetes | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.57 [0.40,0.80] | 0.002 |

| Arthritis | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.92 [0.74,1.15] | 0.44 |

| Coronary Artery Disease | --- | --- | --- | --- | 1.11 [0.83,1.47] | 0.48 |

| Cancer | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.94 [0.73,1.20] | 0.60 |

| Constant | 0.37 [0.31,0.44] | <0.001 | 0.78 [0.50,1.21] | 0.26 | 0.86 [0.54,1.38] | 0.52 |

Multivariable models listed above are represented as odds ratios [95% confidence intervals]. Each model is represented vertically with co-variates. Model 1: age, gender; Model 2: age, gender co-variates, race, education, smoking; Model 2 co-variates, diabetes, arthritis, coronary artery disease, and cancer.

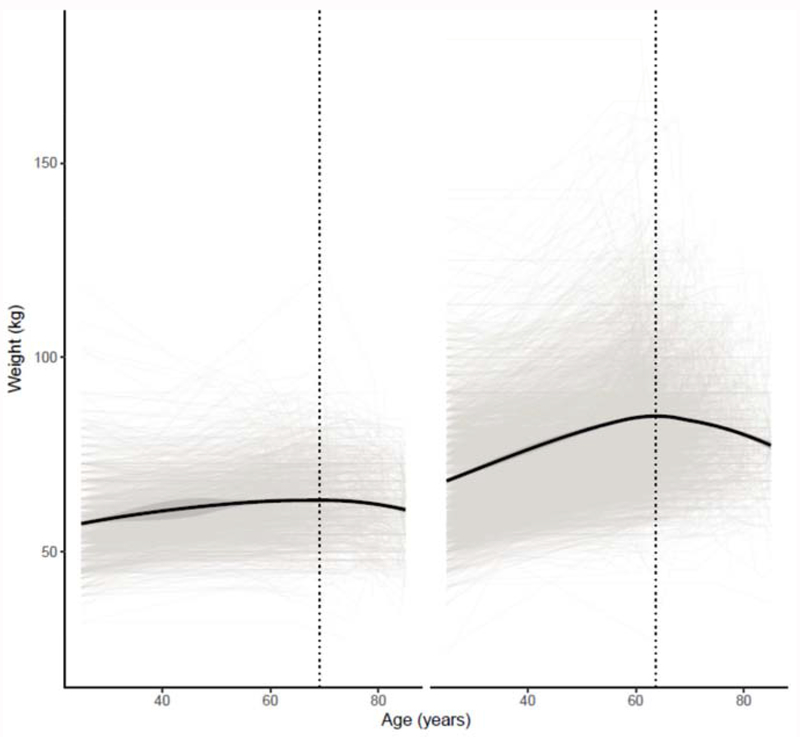

Appendix 7: Change in Weight by Low Lean Mass Status (Appendicular Lean Mass)

The figure represents a LOESS model plot that demonstrates changes in weight status (in kilograms) by age status. Panel (a) represents trajectory of participants fulfilling Low Lean Mass Criteria (men: ALM<19.75kg; women <15.02kg[2]), while panel (b) represents participants that do not fulfill the criteria.

Title: Weight as a Person Ages by Low Lean Mass Status

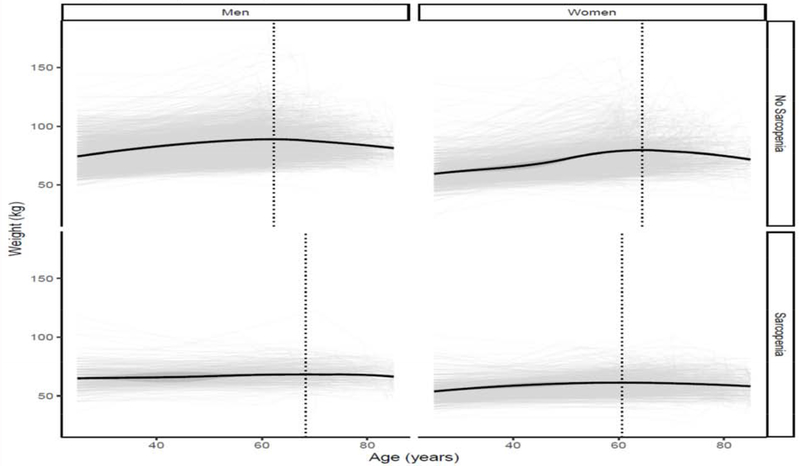

Appendix 8: Change in Weight by Sarcopenia Status by sex

The figure represents a LOESS model plot that demonstrates changes in weight status (in kilograms) by age status. Panel (a) represents males: i) trajectory of participants fulfilling Low Lean Mass Criteria (ALM<19.75kg); ii) represents participants that do not fulfill the criteria. Panel (b) represents females: i) trajectory of participants fulfilling Low Lean Mass Criteria (ALM<15.02kg); ii) represents participants that do not fulfill the criteria

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Work presented at the 2018 International Frailty & Sarcopenia Conference, Miami Beach, FL, March 2018.

There are no conflicts of interest pertaining to this manuscript

REFERENCES

- [1].Sayer AA, Syddall H, Martin H, Patel H, Baylis D, Cooper C. The developmental origins of sarcopenia. J Nutr Health Aging. 2008;12:427–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Studenski SA, Peters KW, Alley DE, Cawthon PM, McLean RR, Harris TB, et al. The FNIH sarcopenia project: rationale, study description, conference recommendations, and final estimates. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69:547–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Stephen WC, Janssen I. Sarcopenic-obesity and cardiovascular disease risk in the elderly. J Nutr Health Aging. 2009;13:460–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Batsis JA, Mackenzie TA, Barre LK, Lopez-Jimenez F, Bartels SJ. Sarcopenia, sarcopenic obesity and mortality in older adults: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2014;68:1001–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kahan S, Kushner RF. Obesity Medicine: A Core Competency for Primary Care Providers. Med Clin North Am. 2018;102:xvii–xix. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Kushner R. What Do We Need to Do to Get Primary Care Ready to Treat Obesity? Obesity (Silver Spring). 2018;26:631–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Wallace JI, Schwartz RS. Involuntary weight loss in elderly outpatients: recognition, etiologies, and treatment. Clin Geriatr Med. 1997;13:717–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Wannamethee SG, Shaper AG, Whincup PH, Walker M. Characteristics of older men who lose weight intentionally or unintentionally. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151:667–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Meltzer AA, Everhart JE. Unintentional weight loss in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142:1039–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Willett WC. Weight loss in the elderly: cause or effect of poor health? Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;66:737–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Ostbye T, Malhotra R, Landerman LR. Body mass trajectories through adulthood: results from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979 Cohort (1981-2006). Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40:240–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M146–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lee JS, Kritchevsky SB, Harris TB, Tylavsky F, Rubin SM, Newman AB. Short-term weight changes in community-dwelling older adults: the Health, Aging, and Body Composition Weight Change Substudy. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:644–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Batsis JA, Gill LE, Masutani RK, Adachi-Mejia AM, Blunt HB, Bagley PJ, et al. Weight Loss Interventions in Older Adults with Obesity: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials Since 2005. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65:257–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Batsis JA, Mackenzie TA, Emeny RT, Lopez-Jimenez F, Bartels SJ. Low Lean Mass With and Without Obesity, and Mortality: Results From the 1999-2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Batsis JA, Mackenzie TA, Jones JD, Lopez-Jimenez F, Bartels SJ. Sarcopenia, sarcopenic obesity and inflammation: Results from the 1999-2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Clin Nutr. 2016;35:1472–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, Ard JD, Comuzzie AG, Donato KA, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS Guideline for the Management of Overweight and Obesity in Adults. Circulation. 2014;129:S102–S38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Batsis JA, Zagaria AB. Addressing Obesity in Aging Patients. Med Clin North Am. 2018;102:65–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Cleveland WS, Grosse E, Shyu WM. Local Regression Models In: Chambers JM, Hastie TJ, editors. Statistical Models in S 1992. p. 309–76. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Newman AB, Lee JS, Visser M, Goodpaster BH, Kritchevsky SB, Tylavsky FA, et al. Weight change and the conservation of lean mass in old age: the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:872–8; quiz 915-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Launer LJ, Harris T, Rumpel C, Madans J. Body mass index, weight change, and risk of mobility disability in middle-aged and older women. The epidemiologic follow-up study of NHANES I. JAMA. 1994;271:1093–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Houston DK, Ding J, Nicklas BJ, Harris TB, Lee JS, Nevitt MC, et al. Overweight and obesity over the adult life course and incident mobility limitation in older adults: the health, aging and body composition study. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169:927–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Houston DK, Ding J, Nicklas BJ, Harris TB, Lee JS, Nevitt MC, et al. The association between weight history and physical performance in the Health, Aging and Body Composition study. Int J Obes (Lond). 2007;31:1680–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Hu Y, Malyutina S, Pikhart H, Peasey A, Holmes MV, Hubacek J, et al. The Relationship between Body Mass Index and 10-Year Trajectories of Physical Functioning in Middle-Aged and Older Russians: Prospective Results of the Russian HAPIEE Study. J Nutr Health Aging. 2017;21:381–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Windham BG, Griswold ME, Wang W, Kucharska-Newton A, Demerath EW, Gabriel KP, et al. The Importance of Mid-to-Late-Life Body Mass Index Trajectories on Late-Life Gait Speed. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017;72:1130–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Stenholm S, Rantanen T, Alanen E, Reunanen A, Sainio P, Koskinen S. Obesity history as a predictor of walking limitation at old age. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2007;15:929–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Rosenblatt NJ, Grabiner MD. Relationship between obesity and falls by middle-aged and older women. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93:718–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Himes CL, Reynolds SL. Effect of obesity on falls, injury, and disability. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:124–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Compston J. Weight change and risk of fracture in postmenopausal women. BMJ. 2015;350:h60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Lv QB, Fu X, Jin HM, Xu HC, Huang ZY, Xu HZ, et al. The relationship between weight change and risk of hip fracture: meta-analysis of prospective studies. Scientific reports. 2015;5:16030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Payette H, Coulombe C, Boutier V, Gray-Donald K. Nutrition risk factors for institutionalization in a free-living functionally dependent elderly population. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:579–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Madigan CD, Pavey T, Daley AJ, Jolly K, Brown WJ. Is weight cycling associated with adverse health outcomes? A cohort study. Prev Med. 2018;108:47–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Artaud F, Singh-Manoux A, Dugravot A, Tavernier B, Tzourio C, Elbaz A. Body mass index trajectories and functional decline in older adults: Three-City Dijon cohort study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2016;31:73–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Williams ED, Eastwood SV, Tillin T, Hughes AD, Chaturvedi N. The effects of weight and physical activity change over 20 years on later-life objective and self-reported disability. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43:856–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Weiss EP, Jordan RC, Frese EM, Albert SG, Villareal DT. Effects of Weight Loss on Lean Mass, Strength, Bone, and Aerobic Capacity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2017;49:206–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Batsis JA, Villareal DT. Sarcopenic Obesity in Older Adults: Definition, etiology, epidemiology, treatment and future directions. Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 2018;[In Press]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Yaari S, Goldbourt U. Voluntary and involuntary weight loss: associations with long term mortality in 9,228 middle-aged and elderly men. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;148:546–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Andres R, Muller DC, Sorkin JD. Long-term effects of change in body weight on all-cause mortality. A review. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:737–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Strandberg TE, Strandberg AY, Salomaa VV, Pitkala KH, Tilvis RS, Sirola J, et al. Explaining the obesity paradox: cardiovascular risk, weight change, and mortality during long-term follow-up in men. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:1720–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Dalton WT 3rd, Wang L, Southerland JL, Schetzina KE, Slawson DL. Self-reported versus actual weight and height data contribute to different weight misperception classifications. South Med J. 2014;107:348–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, Boirie Y, Bruyere O, Cederholm T, et al. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing. 2018:afy169-afy. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Batsis JA, Germain CM, Vasquez E, Bartels SJ. Prevalence of weakness and its relationship with limitations based on the Foundations for the National Institutes for Health project: data from the Health and Retirement Study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016;70:1168–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Kim TN, Yang SJ, Yoo HJ, Lim KI, Kang HJ, Song W, et al. Prevalence of sarcopenia and sarcopenic obesity in Korean adults: the Korean sarcopenic obesity study. Int J Obes (Lond). 2009;33:885–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Lee CG, Boyko EJ, Strotmeyer ES, Lewis CE, Cawthon PM, Hoffman AR, et al. Association between insulin resistance and lean mass loss and fat mass gain in older men without diabetes mellitus. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:1217–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Lim S, Kim JH, Yoon JW, Kang SM, Choi SH, Park YJ, et al. Sarcopenic obesity: prevalence and association with metabolic syndrome in the Korean Longitudinal Study on Health and Aging (KLoSHA). Diabetes Care. 2010;33:1652–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Barzilay JI, Cotsonis GA, Walston J, Schwartz AV, Satterfield S, Miljkovic I, et al. Insulin resistance is associated with decreased quadriceps muscle strength in nondiabetic adults aged >or=70 years. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:736–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]