The proteome of Salmonella-modified membranes has been extracted using an affinity-based proteome approach. The data highlight communalities between the compartment in epithelial and phagocytic cells, but also provide evidence for cell-specific adaptations in Salmonella pathogen-containing compartments. These observations provide novel insights into the mechanisms of host-dependent differences in the pathophysiology of Salmonella infections.

Keywords: Affinity proteomics, host-pathogen interaction, pathogens, bacteria, virulence, subcellular analysis, immune cells, intracellular trafficking, Salmonella

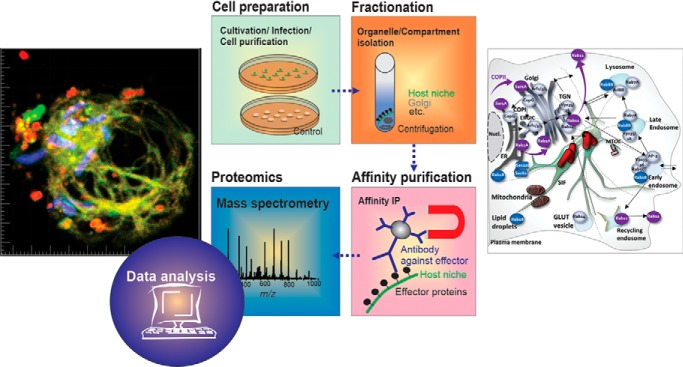

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

Affinity-based proteomics of infected macrophage cells.

Salmonella-modified membranes exhibit host-specific composition.

Proteome differences explain some host-dependent pathophysiological differences.

Abstract

Systemic infection and proliferation of intracellular pathogens require the biogenesis of a growth-stimulating compartment. The gastrointestinal pathogen Salmonella enterica commonly forms highly dynamic and extensive tubular membrane compartments built from Salmonella-modified membranes (SMMs) in diverse host cells. Although the general mechanism involved in the formation of replication-permissive compartments of S. enterica is well researched, much less is known regarding specific adaptations to different host cell types. Using an affinity-based proteome approach, we explored the composition of SMMs in murine macrophages. The systematic characterization provides a broader landscape of host players to the maturation of Salmonella-containing compartments and reveals core host elements targeted by Salmonella in macrophages as well as epithelial cells. However, we also identified subtle host specific adaptations. Some of these observations, such as the differential involvement of the COPII system, Rab GTPases 2A, 8B, 11 and ER transport proteins Sec61 and Sec22B may explain cell line-dependent variations in the pathophysiology of Salmonella infections. In summary, our system-wide approach demonstrates a hitherto underappreciated impact of the host cell type in the formation of intracellular compartments by Salmonella.

Macrophages are central players in innate and adaptive immune defense, directly neutralizing pathogens by phagocytosis and orchestrating responses of other immune cells. Beyond their role as guardians, macrophages themselves are also prime targets for several intracellular pathogens (1, 2). These pathogens evolved strategies to evade intracellular killing and can proliferate within macrophages.

Salmonella enterica strains are one of these pathogens, responsible for estimated 550 million incidences of salmonellosis with 155,000 annual deaths worldwide (3). Especially in immunocompromised and malnourished individuals, S. enterica infection can manifest in form of life-threatening systemic infections with mortality rates of 20–25% (4–6). After internalization by the host, Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium (STM) modifies the phagosome in which it resides into the so-called Salmonella-containing vacuole (SCV)1 (7) to prevent its degradation by the host. Following an extensive interplay with the host endosomal system, the SCV matures into an extensive tubular network with certain properties of late endosomes (8, 13, 9, 10). The host remodelling processes are instigated in early stages by secreted virulence proteins, so-called effector proteins, of the Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 (SPI1) and subsequently substituted by SPI2 effectors (9, 11, 12). These effectors are responsible for the formation of an extensive network of Salmonella-induced tubules (SITs) arising from the SCV (13, 14). Within this tubular network, the Salmonella-induced filaments (SIFs) marked by lysosome-associated membrane protein 1 (Lamp1), are one of the most abundant tubular elements (9, 13). The fully developed compartment is here referred to as a pathogen-containing compartment (PCC) and this extensive maturation from a SCV to PCC is required for successful intracellular replication of STM (14, 15).

The origin and composition of host membranes forming the PCC is of special interest, as those components enable nourishment and protection, which ultimately stimulate STM proliferation. As a whole, we refer to the host membranes that have been acquired and modified by STM as Salmonella-modified membranes (SMM). Although originally believed to mainly originate from the endosomal system, recent proteomic studies have identified a much more complex composition of the SCV as well as mature PCCs (16, 17). However, these studies were conducted in HeLa cells and there is evidence that in macrophages the development of the PCC may be different (18–21). These differences likely contribute to phenotypic variations observed during the infection of macrophages by STM. For example, in HeLa cells STM frequently escape the SCV and replicate within the host cell cytosol (22–24), whereas in macrophages a stable population of cytosolic STM has not been detected (25–27). Replication rates of STM seem to vary with host cell types and studies suggest differences in effector protein expression and host target utilization (19, 20, 28–30). For example, STM target different small Rab GTPase when infecting macrophages compared with HeLa cells (31, 32). Together, these findings suggest that STM might hijack different host elements when infecting distinct cell types. As a consequence, it can be expected that the SMM composition will reflect these divergent host sources. However, only limited information is available regarding the SMM composition in infected macrophage cells.

Recently, we developed an affinity-based proteome approach for the systematic elucidation of the composition and sources of SMMs in HeLa cells (16). Here we applied a similar approach to investigate the SMM proteome in murine macrophages. A subsequent comparison of SMM proteomes from different cell lines provides insights into the variation of Salmonella PCCs and helps explain observed physiological variation in the intracellular life of Salmonella.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Chemicals

If not further indicated, chemicals were obtained from Sigma Aldrich (Steinheim, Germany). Cell lines, bacterial strains and their cultivation-RAW264.7 (ATCC no. TIB-71) and RAW264.7 LAMP1-GFP cells (10) were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing 4.5 g × l−1 glucose and 4 mm stable glutamine (Biochrom, Berlin, Germany) supplemented with 6% inactivated fetal calf serum (iFCS). HeLa (ATCC No. CCL-2) and HeLa LAMP1-GFP were maintained in DMEM containing 4.5 g × l−1 glucose, 4 mm l-glutamine, sodium pyruvate (Biochrom) and 10% iFCS. Cell lines were incubated at 37 °C in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2 and 90% humidity. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium strains NCTC12023 (wild type, WT) or ΔsseF (HH107) and ssaV (P2D6), both harboring p3711 for synthesis of SseF-2TEV-2M45, were used in this study (details see supplemental Table S1). Strain ssaV is defective in the Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 (SPI2)-encoded type III secretion system (T3SS) and unable to translocate SPI2-T3SS effector proteins. For live cell imaging, WT and ssaV harboring pFPV25.1 or pFPV-mCherry/2 were used for constitutive expression of GFP or mCherry, respectively (supplemental Table S1). Salmonella strains were routinely cultured in Lysogeny Broth (LB) broth at 37 °C with aeration containing 50 μg × ml−1 carbenicillin (Carl Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany) or 12.5 μg × ml−1 chloramphenicol if required for the selection of plasmids.

Transfection Constructs

To generate plasmids expressing diverse candidate host proteins, host genes were amplified from the cDNA clone library (ASU, AZ, USA) and via Gibson assembly N- or C-terminally fused to eGFP encoded on pEGFP-N1 or pEGFP-C1 (Takara Bio Europe SAS/Clontech, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France). Transfection vectors used in this study are summarized in supplemental Table S1. Localization of fusion proteins were validated in non-infected cells.

Infection of RAW and HeLa Cells

RAW or RAW LAMP1-GFP cells were infected with overnight cultures of Salmonella with a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 25 or 50 for SMM enrichment or immunostaining, respectively. Bacteria were centrifuged onto the cells at 500 × g for 5 min, and infection proceed for further 25 min at 37 °C in an atmosphere with 5% CO2. Subsequently, cells were washed thrice with warm PBS and incubated with medium containing 100 μg × ml−1 gentamicin (AppliChem, Darmstadt, Germany) to kill non-invaded bacteria for 1 h. Finally, the medium was replaced by medium containing 10 μg × ml−1 gentamicin for the rest of the experiment. HeLa cells were infected with 3.5 h cultures as described before (16). For live-cell imaging, a MOI of 50 was used for both cell lines.

Transient Transfection of RAW Cells and HeLa Cells

Cell lines were cultured for 1 day in 8-well chamber slides (Ibidi, Gräfelfing, Germany) and transfected with FUGENE HD reagent (Promega, Walldorf, Germany) according to manufacturer's instruction. In brief, 0.5–1 μg of plasmid DNA was solved in 25 μl cell culture medium without iFCS and mixed with 1–2 μl FUGENE reagents (ratio of 1:2 for DNA to FUGENE). After 10 min incubation at room temperature (RT) the transfection mix was added to the cells in DMEM with 10% iFCS for at least 18 h. Before infection the cells were provided with fresh medium without transfection mix. Transfection constructs are listed in supplemental Table S1.

Immunostaining

Immunostaining was performed as described before (33). Briefly, infected RAW LAMP1-GFP cells (MOI 50) were fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde (PFA) at 4, 8, 12, and 16 h p.i., washed with at 4, 8, 12, and 16 h p.i., washed with PBS and incubated for 30 min in blocking solution (2% goat serum, 2% BSA and 0.1% saponin in PBS) before incubated with anti-M45 (1:500) as primary antibody and anti-mouse-Cy5 as secondary antibody (supplemental Table S1) for 1 h at RT.

Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy

Before live-cell imaging, medium was replaced by Minimal Essential Medium (MEM BioChrom) with Earle's salts, without NaHCO3, l-glutamine and phenol red but supplemented with 30 mm HEPES, pH 7.4. Fluorescence imaging was mainly performed using the Leica SP5 confocal laser-scanning microscope (CLSM) with live-cell periphery, equipped with an incubation chamber maintaining 37 °C and humidity. Used objectives were 10× (HC PL FL 10× , NA 0.3), 20× (HC PL APO CS 20×, NA 0.7), 40× (HCX PL APO CS 40× , NA 1.25–0.75) and 100× objective (HCX PL APO CS 100×, NA 1.4–0.7) and the polychromic mirror TD 488/543/633 for the three channels GFP/RFP/BF (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). The LAS AF software (Leica) was used for setting adjustment, image acquisition and image processing. For time-resolved experiments, spinning disk microscope (Zeiss Cell Observer with Yokogawa Spinning Disc Unit CSU-X1a 5,000, Evolve EMCCD camera, Photometrics, Göttingen, Germany) with live-cell periphery was used, equipped with an Alpha Plan-Apochromat 63× (NA 1.46) oil immersion objective (Zeiss). Images were acquired with the following filter combinations: mTurquoise2 with BP 485/30, GFP with BP 525/50, mCherry with LP 580 and processed by the ZEN2012 (Zeiss) software. Scale bars for all acquired images were added with Photoshop CS6 (Adobe). 3D movies were generated with the software Imaris (Bitplane, Zürich, Switzerland).

Quantitation by Flow Cytometry Analyses

RAW cells were infected either with Salmonella ΔsseF or ssaV, harboring p3711 for synthesis of SseF-2TEV-2M45, as described before. At 4, 8, 12, and 16 h p.i. cells were fixed with 3% PFA in PBS, permeabilized with 0.1% saponin in 10% iFCS/PBS, stained primary with anti-M45 (1:1000) and secondary with anti-mouse IgG Alexa Fluor 488 (1:1,000) (supplemental Table S1) for subsequent flow cytometric analyses using FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences, Heidelberg, Germany). Experiments were performed in triplicates at least three times. Data were analyzed with FACS Express 4 (De Novo Software, Pasadena). Statistical analyses were performed using Student's t test with SigmaPlot 11 (Systat Software, Erkrath, Germany).

Immunoprecipitation, SDS-PAGE and Western Blotting

SMM-enriched fraction and immunoprecipitation were prepared with some minor adjustments as described before (16). Briefly, about 1.6 × 108 RAW cells were used per immunoprecipitation (IP) and biological replicate. Before cell homogenization, infected host cells were rinsed thrice with PBS, scraped, resuspended in 10 ml osmostabilizing homogenization buffer (250 mm sucrose, 20 mm HEPES, 0.5 mm EGTA, pH 7.4), centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 10 min and resuspended in 1 ml of 4 °C pre-cooled homogenization buffer with 1× protease inhibitor mixture (Serva, Heidelberg, Germany). Afterward, host cells were mechanically disrupted with 0.5 mm glass beads (Scientific Industries/Fisher Scientific, Schwerte, Germany) using the Vortex-2 Genie with Turbomix (Scientific Industries; 5 × 1 min strokes) with intermediate cooling. To remove non-lysed host cells, the lysate was centrifuged at 100 × g for 5 min at 4 °C. The immediate supernatant was centrifuged at 8,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C to obtain the SMM-enriched fraction (pellet). This pellet was then washed twice with pre-cooled homogenization buffer with protease inhibitor mixture, before re-suspended in 500 μl homogenization buffer supplemented with 1.5 mm MgCl2 and treated with DNaseI (50 μg × ml−1) for 30 min at 37 °C. Protein concentration was afterward determined via Bradford assay (BioRad, Feldkirchen, Germany). Per IP, 25 μl Protein G magnetic beads (GE, Freiburg, Germany) were coated with 40 μg purified anti-M45 antibody on a rotary shaker at 4 °C overnight. The beads were washed twice with PBS, cross-linked according to the manufacturer's instruction and blocked for 30 min with 1% BSA in PBS at 4 °C. 500 μg of the SMM-enriched fraction were adjusted to a final volume of 200 μl in resuspension mix (1.5 mm MgCl2, 10 mm KCl, 0.1% NP-40) and then incubated with 25 μl cross-linked anti-M45 antibody labeled Protein G magnetic beads on a rotary shaker at 4 °C overnight. To remove unbound proteins, the sample was five-times washed with 0.1% NP-40 in PBS. Finally, bound proteins were eluted in 25 μl 1 x SDS sample buffer (12.5% glycerol, 4% SDS, 2% mercaptoethanol, 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.8). As before (16), proteins were separated on 12% SDS-PAGE for Western blotting and 4–12% gradient gels (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Dreieich, Germany) for MS analysis using the NuPAGE MOPS buffer system.

Experimental Design and Statistical Rationale

In total, six independent IP proteome experiments were performed; three biological replicates of RAW cells infected with STM ΔsseF [p3711] and three infected with the control strain STM ssaV [p3711], a mutant lacking (intracellular) replication and SIF network formation. Proteins were only considered as part of the SMM proteome if identified in at least in two biological replicates and absent in the control (supplemental Table S2). This comparison allows the identification of proteins specific to mature SMMs. Protein abundance was estimated using the exponentially modified protein abundance index (emPAI) and listed in supplemental Table S2. Statistical analyses of abundance differences were performed using Student's t-test and adjusted for multiple hypothesis testing with the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure.

Protein Digest, RP-LC Separation, MS and Data Analysis

Digests, RP-LC and MS were conducted as described before (16). Briefly, eluted proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, Coomassie Blue-stained, sliced into 33 gel pieces and subjected individually to standard in-gel de-staining and trypsinolysis (34). Afterward, digests were transferred into vials, resulting in a total of 198 digested samples. LC MS/MS analysis was performed using an UltiMate 3000 NCS-3500 nano-HPLC system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) controlled by Chromeleon chromatography software coupled to the AmaZon ETD speed ion trap MS with CaptiveSpray source (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany). The UltiMate 3,000 NCS-3,500 nano-HPLC system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was configured with a 2 cm PepMap 75-μm-i.d. C18 sample trapping pre-column (Thermo Fischer Scientific) and a 15-cm PepMap 75-μm-i.d. C18 microcapillary column (Thermo Fischer Scientific). Seven microliters per samples were injected, trapped and separated by a 60-min linear gradient from 5 to 50% solvent B (80% ACN, 0.1% v/v formic acid) with 300 nl × min−1 flow rate. For each MS scan, up to eight abundant multiply charged species in the m/z 400–1,600 range were automatically selected for MS/MS but excluded for 30 s after having been selected twice. The HPLC system was controlled using Compass 1.5 (Bruker). Acquired MS/MS data were processed by the ProteinScape 3.1 software (Bruker) and searched against the UniProt Mus musculus database (12/2014, 16,696 entries) using the ProteinExtractor algorithm, a proprietary meta-algorithm integrating Mascot Score (Bruker). Spectral data are available in PeptideAtlas (PASS01384, PASS01470 www.peptideatlas.org/). Data analyses were conducted according the published guidelines (35). Mass tolerance values for MS and MS/MS were set at 0.8 Da and 4 Da. Fixed search parameters were tryptic digestion and miss cleavage up to 1. Variable search parameters used for the search were deamidation (NQ), carboxymethyl (C) and oxidation (M). Proteins were considered as identified with ProteinScape score >40 and two unique peptides with >95% confidence. Peptide Decoy (Mascot) and FDR was adjusted to 1% at protein and peptide level for all experiments.

All identified proteins were searched against the UniProt-GOA database (36). Only proteins identified in two biological replicates were considered as a candidate of the SMM proteome (supplemental Table S2A) and grouped with PANTHER Classification System (www.pantherdb.org) (37) according their Gene Ontology (GO). To compare the composition of pathogen-modulated host compartments from different pathogens and hosts, the MGI vertebrate homology database to extract human-mouse homologs (www.informatics.jax.org/homology.shtml) was used (38).

Functional Analyses of SMM Candidates

We performed site-directed mutagenesis in transfection vectors containing genes encoding Rab GTPases Rab8B, Rab18 and Arl8B in order to create dominant negative (DN) alleles. The mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing and the expression of the fusion proteins was confirmed by transient transfection of RAW264.7 macrophages. For transfection, plasmid DNA was isolated using Endofree plasmid preparation kits (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). RAW264.7 macrophages were cultured for 1 day in 12-well cell culture plates (Techno Plastics Products, Trasadingen, Switzerland) and transfected with FUGENE HD reagent (Promega) according to manufacturer's instruction. In brief, 21.5 μg of plasmid DNA was solved in 50 μl cell culture medium without iFCS and mixed with 43 μl FUGENE reagent (ratio of 1:2 for DNA to FUGENE). After 10 min incubation at room temperature (RT) the transfection mix was added to the cells in DMEM with 10% iFCS for at least 18 h. Before infection, the cells were provided with fresh medium without transfection mix. RAW264.7 cells were infected with STM WT or ssaV strains as described before. The bacterial strains harbored pFPV-mCherry for constitutive expression of mCherry. At 1 and 16 h p.i, macrophage cells were washed, detached form the culture plates, and analyzed by flow cytometry using an Attune NxT cytometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). At least 10,000 GFP-positive RAW264.7 cells were analyzed, mCherry fluorescence intensity quantified and mean intensities for mCherry fluorescence were calculated.

RESULTS

SIF Network Formation and Translocation of Effector SseF in RAW Macrophages

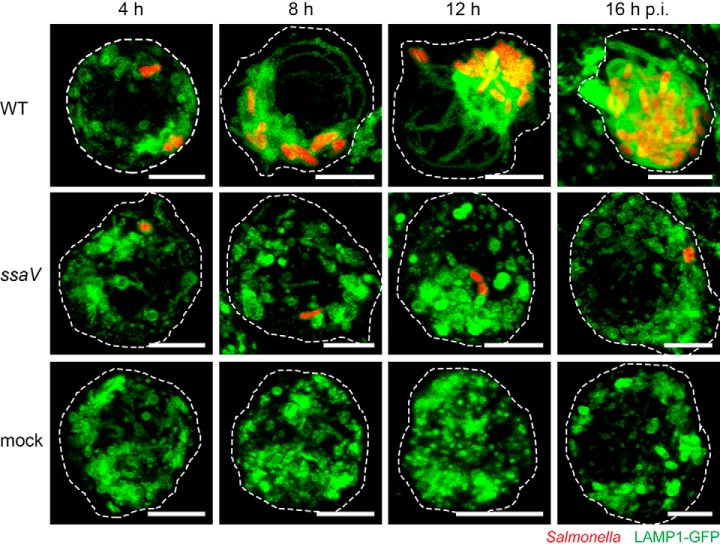

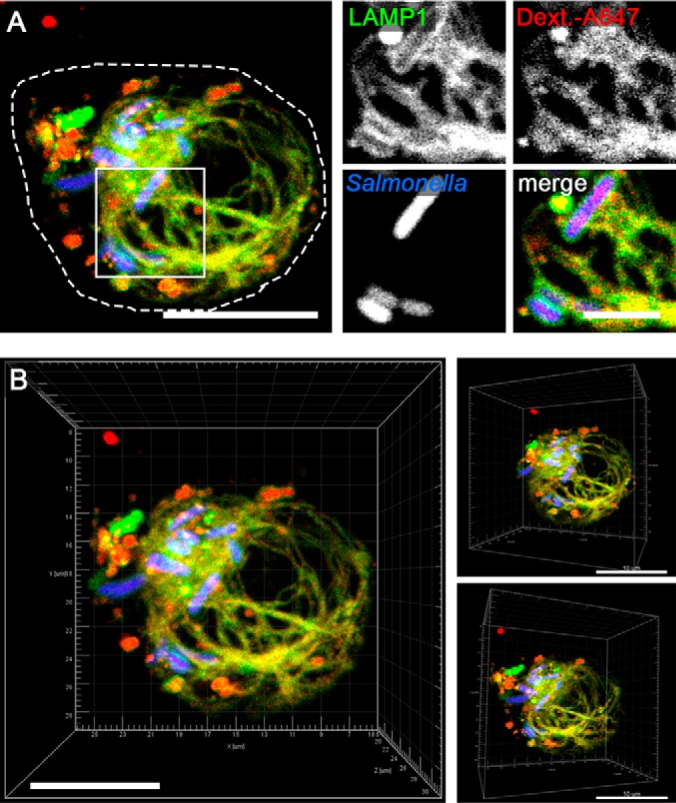

First we characterized the SIF development in the murine macrophage cell line RAW264.7 (RAW). We infected the stably transfected RAW LAMP1-GFP cell line with wild type Salmonella enterica sv. Typhimurium (STM WT) constitutively expressing mCherry and visualized the infection process by live cell microscopy from 4–16 h post infection (p.i.). The lysosomal membrane-integral glycoprotein LAMP1 was used as marker to continuously monitor SIF development and SMM formation. As controls we used non-infected cells (mock), as well as cells infected with STM ssaV, a strain that is unable to translocate effector proteins, and thereby is deficient in inducing SIF network formation. As expected, we observed no indication of SIF network formation in the controls (mock and ssaV mutant) at any time point, whereas STM WT-infected macrophages showed small SIF networks at 8 h p.i. (Fig. 1). During the following hours, the network size in STM WT-infected macrophages increased until it reached its maximum at 12 h p.i. 3D-representation of maximum intensity projections revealed that at this time point SIFs were extensively branched and the network was completely enclosing the nucleus (Fig. 2). Furthermore, pulse-chase labeling with the endocytic tracer Dextran Alexa647 showed that most endocytic vesicles co-localized with LAMP1-GFP at the SIF networks and the SCV.

Fig. 1.

SIF network in STM-infected macrophages is maximal extended at 12 h p.i. RAW cells expressing LAMP1-GFP (green) were infected with STM WT or ssaV expressing mCherry (red). Regular LAMP1-expression was monitored in uninfected cells (mock). Live-cell imaging was performed every hour from four to 16 h p.i. Representative images of a STM-infected or non-infected cells are shown. Scale bar: 5 μm.

Fig. 2.

Salmonella forms a complex SIF network in macrophages. A, RAW cells expressing LAMP1-GFP (green) were pulse-chased with fluid tracer Dextran Alexa 647 (red) and infected with STM WT expressing mCherry (STM, blue). Live cell imaging was performed 12 h p.i. Endocytic fluid tracer Dextran Alexa647 co-localizes with LAMP1-GFP positive SIF structures. Merge is shown as maximum intensity projection (MIP); magnifications are presented as individual layer. B, 3D visualization of SIF network as MIP. Scale bar: 10 μm.

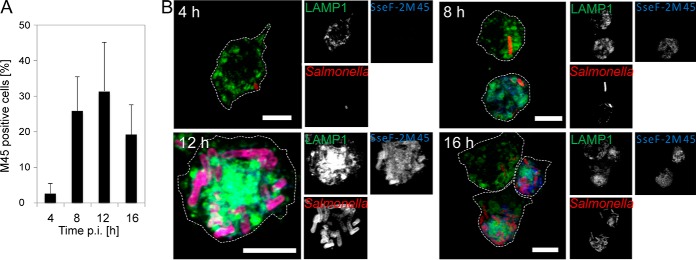

As we use the prominent membrane-integral translocated SPI2-T3SS effector protein SseF as bait for SMM enrichment (16), we next analyzed its presence in macrophages SIFs. We used flow cytometry for quantitation of the M45-tagged SseF and immunostaining to visualize its translocation in macrophages (Fig. 3). At 4 h p.i., we observed 2% effector-positive M45-stained macrophages (Fig. 3A). The rate increased to roughly 20% at 8 h p.i. and reached its maximum of around 30% at 12 h p.i. Afterward the rate declined to roughly 20%. Measuring the relative fluorescence intensity (RFI) of the M45 signal enabled us to determine the relative amount of effector in proportion to M45-positive cells or all cells. The highest values for the M45-positive cells were obtained at 12 h and 16 h p.i. (supplemental Fig. S1A). In addition, RFI measurement of the M45 signal in the complete cell population displayed the highest RFI values at 12 h p.i. (supplemental Fig. S1B). Immunostaining confirmed co-localization of the bait protein SseF with LAMP1 and a maximum of SseF abundance in SIFs at 12 h p.i. (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

SseF effector accumulation and SseF-positive macrophages are maximal at 12 h p.i. A, percentage of infected RAW cells positive for M45 were determined at indicated time points by flow cytometry. Shown are the mean values (+ standard deviation) of three independent experiments. B, stable transfected RAW cells expressing LAMP1-GFP (green) were infected with STM ΔsseF synthesizing SseF-2TEV-2M45 (SseF, blue) and mCherry (STM, red), fixed and immuno-stained with anti-M45 and anti-IgG-Cy5 at 4, 8, 12, and 16 h p.i. Representative micrographs are shown as maximum intensity projection. Scale bar: 5 μm.

In summary, in macrophages the maximal SIF network extension is reached at 12 h p.i., coinciding with the highest number of SseF-positive cells and amount of detectable effector per cell. Thus, we used this infection condition for SMM profiling in murine macrophages.

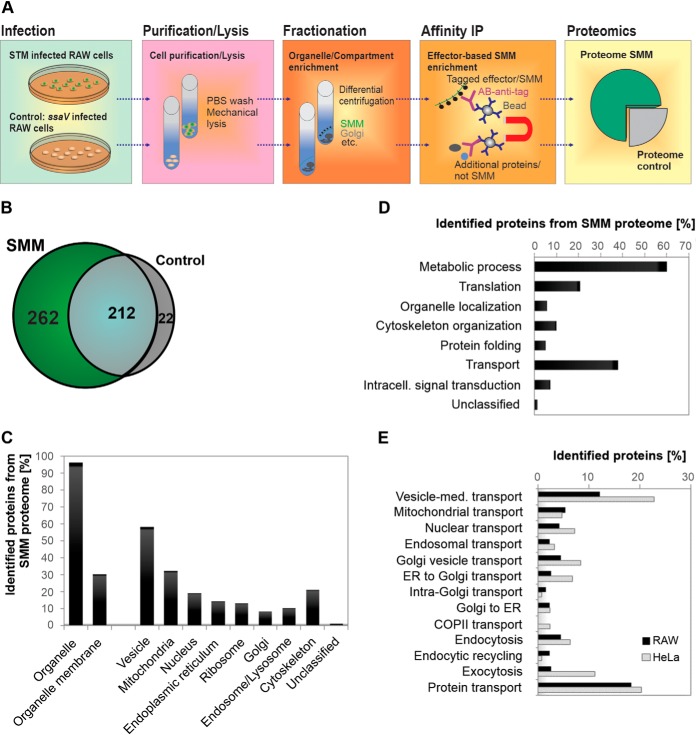

SMM Composition in RAW Macrophages

To determine the SMM composition in murine macrophages, we used the previously established three-step approach (16), in which cell purification/lysis is followed by intracellular compartment enrichment and affinity immuno-precipitation (IP) (Fig. 4A). Briefly, we infected ∼1.6 × 108 RAW cells with STM ΔsseF [p3711], or STM ssaV [p3711] as negative control and harvested cells at 12 h p.i. After homogenization, the SMM fraction was enriched by differential centrifugation. We confirmed the presence of the tagged effector SseF-2TEV-2M45 in the SMM-enriched fraction via Western blotting (supplemental Fig. S2A), before the samples were used for IP followed by LC-MS/MS analyses. We profiled six IP preparations, three biological replicates of RAW cells infected with STM ΔsseF [p3711] and three biological replicates infected with the control strain STM ssaV [p3711], a mutant lacking intracellular replication and SIF network formation. Protein samples were pre-separated by SDS gel electrophoresis and bands were excised and digested for LC-MS/MS analyses. In total we identified 728 host proteins, of which 232 proteins were only observed in one biological replicate, reducing the set of reproducibly observed host proteins to 496. Of these (Fig. 4B), 212 proteins were also detected in the negative control proteome of cells infected with STM ssaV. Statistical analysis of their protein abundance revealed no significant difference between the control proteins and the STM ΔsseF [p3711] of infected RAW proteins. Accordingly, the shared proteins do not appear to be specific to the infection process and were not further considered. We note that without adjustment for multiple hypothesis testing we found an increase predominantly of ribosomal and ER-associated proteins. Further 22 proteins were only detected in the control. In total we therefore considered 262 host proteins as part of the reproducible SMM proteome isolated from macrophages (supplemental Table S2).

Fig. 4.

Global analyses of the macrophages derived SMM proteome. A, scheme for SMM profiling. B, Venn-diagram of identified proteins. In total 728 proteins were identified, of which 262 were reproducibly identified as part of SMM. C, classification of the 262 SMM proteins according to PANTHER Gene Ontology (GO) subcellular component. D and E, categorization of identified SMM proteins according to PANTHER GO biological processes as well as transport processes. Proteins in C - E can have multiple assignments.

We then classified the identified macrophage SMM proteins according their predicted or experimentally determined subcellular location (GO cellular component) and their involvement in biological functions (GO biological process) using the PANTHER classification system (37). These analyses revealed that most of the identified SMM proteins are part of vesicles (58%). In addition, a significant number of SMM proteins was found to originate from diverse host organelles, including mitochondria (32%), nucleus (19%), ER (13%), ribosomes (13%), endosomes/lysosomes (10%), Golgi (8%) and the cytoskeleton (21%) (Fig. 4C). Comparing the distribution using quantitative values yielded similar results with a slight increase of proteins associated with nucleus (24%) and ribosomes (21%) (supplemental Fig. 2B). Many of the identified SMM proteins are involved in transport processes (40%, Fig. 4D). A closer analysis of these proteins revealed that among the transport proteins a plurality is involved in vesicle-mediated and protein transport. A smaller subgroup is specifically involved in the directed transport from Golgi to ER, intra-Golgi or ER to Golgi, endosomal trafficking, endocytosis, recycling, and exocytosis processes (Fig. 4E).

As we already generated an SMM proteome data set for HeLa cells (16), we proceeded to compare both SMM proteomes. In both studies we identified a similar number of SMM proteins (RAW: 262 and HeLa: 247) and observed a similar distribution according to PANTHER GO cellular compartment and biological processes (supplemental Fig. S3A, S3B). Minor differences were found in nuclear and vesicle-related proteins as well as number of proteins involved in translation and transport. However, when focusing on transport-related processes, overall fewer proteins involved in vesicle-mediated transport were identified in infected macrophages (11%) compared with HeLa cells (22%) (Fig. 4E). Likewise, exocytic pathways (2% in RAW and 11% in HeLa) as well as transport from ER to Golgi (2% in RAW and 6% in HeLa) were also less prominent at PCCs in macrophage. A comparison of the identified proteins on the individual level only showed a 19% overlap between the identified SMM proteins (supplemental Fig. S3C). A closer analysis revealed that part of the difference can be attributed to the identification of different subunits from multimeric protein complexes in the SMM proteomes. When we group different subunits of a given protein complex together, we found that the overlap between the two data sets increased to 59%. As expected, among the proteins identified in both SMM proteomes a high proportion were components of diverse host trafficking routes, such as elements of the endocytic and secretory vesicle transport including small GTPases Rab5C, Rab14A, Rap1A, RalA and G3bp2, components of the COPI-mediated transport (e.g. CopA, CopG1) or clathrin-mediated endocytosis as the adaptor protein complex (e.g. Ap2B1). Likewise, cytoskeletal components known to mobilize vesicles and stabilize PCC such as myosin-9, dynein, α-actinin-1, Arp2/3 and the actin capping complex, were prominent in both cell lines. In contrast, we did not find any evidence for an interference of STM in vesicle trafficking mediated by the COPII system in infected RAW cells, which is in contrast to our previous proteomic data in HeLa cells. In addition, we identified organelle-associated proteins such as the ER proteins Rpn2, VapA and Tmed10 or the mitochondrial protein Trap1 in both studies.

Together, the data suggest that STM targets a similar core set of host membrane sources in both cell lines, but also seems to fine-tune them on the individual protein level to the respective host cell type. In addition, the proteomic investigation also suggests a significant impact of non-canonical host elements such as the ER and mitochondria.

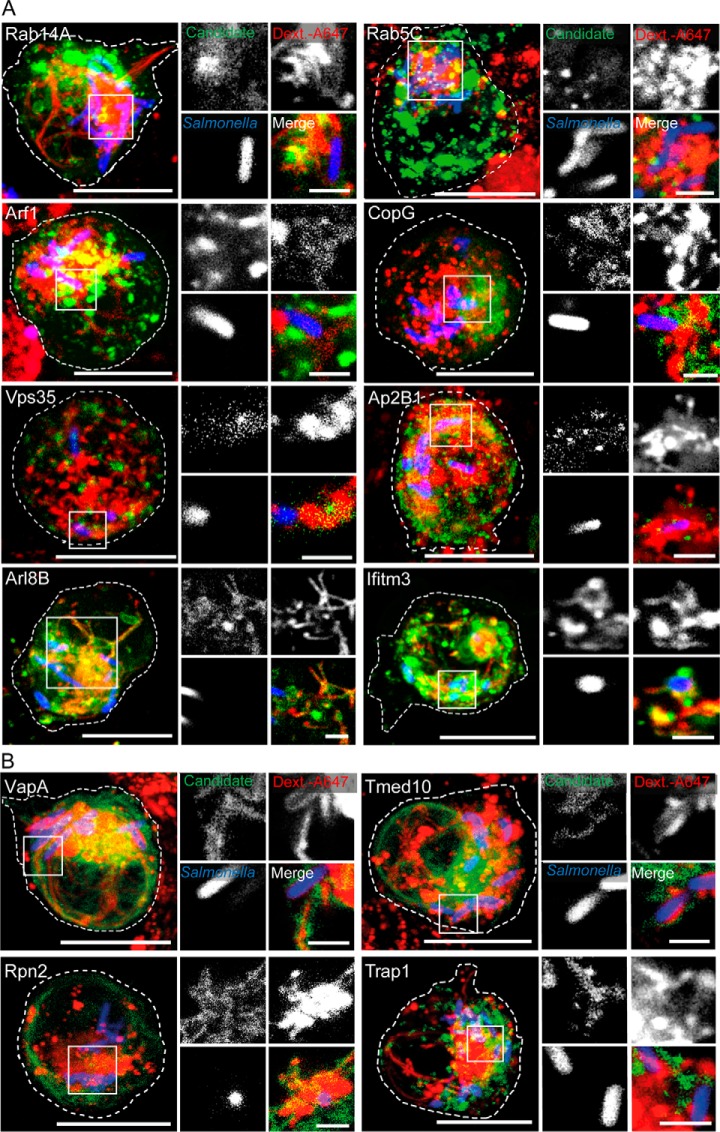

Live-Cell Imaging of SMM Proteins

To elaborate on the proteome data, we conducted live-cell imaging with selected SMM candidates identified by our affinity-based proteome approach as chemical fixation rapidly fragment the mature PCC. We designed transfection vectors for expression of GFP-fusions of 18 SMM candidates from different known trafficking routes and host organelles. We then transiently transfected RAW cells with those GFP-fused SMM candidates and monitored expression and cellular localization of the GFP-fusions in non-infected host cells to establish their regular expression pattern (supplemental Fig. S4). Subsequently, we analyzed the localization of these SMM candidates during STM infection. We infected transiently transfected RAW cells with STM WT constitutively expressing mCherry for visualization of the pathogen, and pulse-chased host cells with endocytic fluid tracer Dextran Alexa647 to follow the endocytic traffic. The first host proteins we analyzed were part of various vesicle trafficking systems previously found to be involved in PCC formation and maturation in Salmonella-infected HeLa cells (16, 39). These include small Rab, Arf and Ras-like GTPases (Rab5C, Rab14, Arf1, Arf3, Rap1), components of the COPI-mediated transport (CopG) and lysosomal traffic (Arl8B and Ifitm3), parts of the retromer complex moderating the transport from endosomes to the trans-Golgi network (Vps35) and the adapter protein complex 2 for endocytic secretory pathways (Ap2B1). In all cases, we observed recruitment of these proteins to the Salmonella PCC in infected macrophages between 10–12 h p.i. (Fig. 5A, supplemental Fig. S5). Thus, the live cell imaging study confirmed the proteomic results and demonstrates vesicle recruitment from various trafficking routes during the PCC maturation in macrophages directed by STM.

Fig. 5.

SMM proteins are localized at SCV or SIFs in infected macrophages. RAW cells were transfected with plasmids encoding GFP-fusions of diverse host proteins (green) involved in A, different trafficking processes such as Rab5C, Rab14A, Arf1, Arf3, Rap1, CopG, Arl8B, Ifitm3, Vps35 and Ap2B1 or B, organelle marker proteins including Rpn2, VapA, Tmed10 and Trap1. Before visualization by CLSM, cells were pulse-chased with Dextran Alexa647 (red) and infected with Salmonella WT continuously expressing mCherry (STM, blue) for 10–12 h p.i. Dextran Alexa647 served as a marker for PCC. Representative overview images (large) are shown as maximum intensity projections. White squares indicate a magnified area. In magnifications, an individual z-plane for each channel is shown. Scale bars: 10 μm (overview); 2 μm (magnification).

Interestingly, the proteomic investigation of the SMM in macrophages, as well as in HeLa cells in our previous study (16), suggests that membranes from organelles such as the ER and mitochondria may also be redirected to the PCC by STM. To investigate this finding in more detail we analyzed the recruitment of three integral ER proteins, the dolichyl-diphosphooligosaccharide-protein glycosyltransferase subunit 2 (Rpn2), the vesicle-membrane-protein-associated protein A (VapA), and the transmembrane emp24 domain-containing protein 10 (Tmed10), as well as the mitochondrial protein Trap1 in infected HeLa as well as RAW cells via life-cell imaging. For this investigation, we transiently transfected HeLa or RAW cells for synthesis of fusion proteins of GFP and the respective SMM proteins and monitored the infection process as previously described. In HeLa cells we detected these organelle marker proteins closely located to the PCC 8 h p.i. (supplemental Fig. S6), whereas in RAW cells the same proteins were detected between 10 and 12 h p.i. (Fig. 5B). Thus, the data indicate that in both cell lines mitochondria and ER contribute to the maturation of STM PCCs. However, the timing appears to be different, with the maturation of the PCC in macrophages being delayed by ∼4 h compared with epithelial cells.

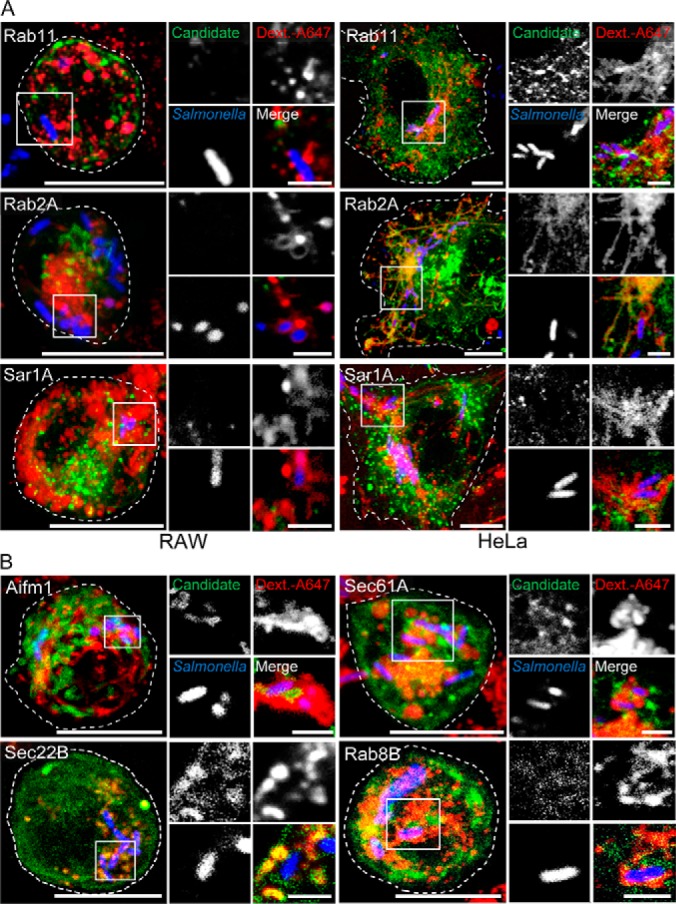

Next, we focused on differences between the SMMs formed in the two cell lines. Based on the proteome data, the SMM in macrophages seems to lack components of the retrograde vesicle transport, like for instance the small GTPases Rab2A, Rab11 and Sar1A. Using live cell imaging we could clearly detect these proteins at the PCC in HeLa cells (Fig. 6A). However, the PCC in macrophages was devoid of these proteins, indicating that they are indeed only manipulated by STM in epithelial cells.

Fig. 6.

Differences between SMMs formed in phagocytic and epithelial host cells. A, CLSM of transfected HeLa and RAW cells show recruitment of small GTPases Rab2A, Rab11 and Sar1A to the PCC in HeLa cells, absent in macrophages. B, re-location of SMM proteins Rab8B, mitochondrial protein Aifm1 and ER transport proteins Sec61 and Sec22B to the PCC of RAW cells. CLSM were performed as described before. Shown are presentative overview images (large) and magnifications of marked areas displayed as individual channel. Scale bars: 10 μm (overview); 2 μm (magnification).

We further investigated proteins that were only found in SMMs of macrophages. Here we focused on the Rab GTPase Rab8B, the mitochondrial protein Aifm1 and ER transport proteins Sec61 and Sec22b. Live cell imaging validated the localization of these proteins at the PCC in RAW cells but they were absent in HeLa cells (Fig. 6B). Thus, the data suggest that although Salmonella accesses similar structures in its host, there are subtle differences in the specific routes that are manipulated. We then set out to investigate the potential impact of three Rab GTPases for the intracellular life-style of Salmonella. Here, we focused on Rab8B and Rab18, which were exclusively identified in SMM proteome of macrophages and ARL8B, which was identified in SMM proteomes of both RAW and HeLa cells. To perturb GTPase function, we generated dominant-negative (DN) versions, and expressed WT as well as mutant alleles of those GTPases as GFP fusions in transiently transfected cells.

Because efficiency of transfection of macrophages generally is rather low, and transfection often reduces the efficacy of bacterial uptake, we developed a flow cytometry-based approach that allowed selective analyses of the transfected and STM-infected subpopulation of RAW cells (supplemental Fig. S7). STM infection was performed with strains constitutively expressing mCherry, and the intensity of mCherry fluorescence served as proxy for phagocytosed STM and intracellular proliferation. We gated on GFP-positive RAW264.7 cells to identify transfected cells and quantified the mCherry fluorescence. We observed that perturbation of the GTPase function of Rab8B, Rab18 and Arl8B led to a mildly increased intracellular proliferation of STM in infected cells.

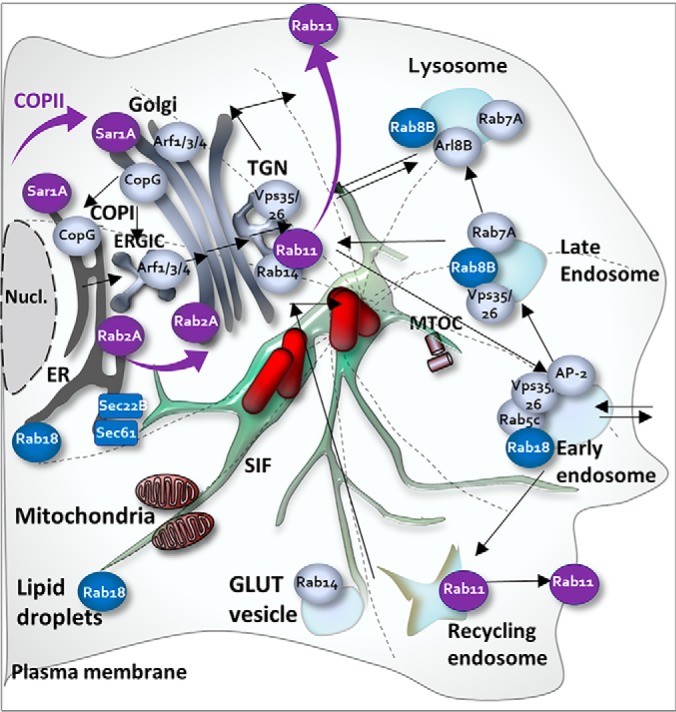

In sum, our systematic approach revealed communalities as well as compelling differences in the infection process both host cell types, which we summarized in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Schematic summary of identified key trafficking pathways targeted by STM. The model indicates communalities (gray) and differences (blue, only observed in RAW; violet, only observed in HeLa) in trafficking proteins relocated to the SMM during the infection of HeLa and RAW cells.

DISCUSSION

Salmonella can infect diverse hosts and cell types and commonly forms characteristic, highly dynamic and extensive tubular membranous PCC which are required for intracellular replication (13, 14). Although it is well established that STM builds a replication-permissive niche in diverse host cells by deploying a complex set of effector proteins, the PCC composition and their cellular origin are only partially explored. Until recently, identification of STM PCC components were mainly executed by fluorescence imaging (immunostaining, GFP-fusions) (18, 31, 40–44) limiting the analyses per study to few host proteins. Recently established proteomic approaches enabled a more systematic viewpoint on PCCs (16, 17, 45). In addition, an increasing number of studies revealed that STM modifies the expression of its effector repertoire depending on the infected host cell type (19, 20, 46, 47), suggesting a careful modulation of the PCC biogenesis in different host cells. To elaborate this hypothesis, we applied our recently established affinity-based proteome approach to profile the SMM composition of STM-infected murine macrophages and compared it with the SMM from the epithelial cell line HeLa (16).

Our data highlight communalities between the compartment in epithelial and phagocytic cells, but also provide evidence for cell-specific adaptations in STM PCCs. A common strategy for biogenesis of PCCs is the manipulation of host traffic routes (48). It was therefore not surprising that the main components of SMM proteomes in HeLa and RAW cells are transport-associated components indicative for diverse intracellular host membrane trafficking routes (49). Conserved elements found in the PCC of HeLa as well as RAW cells were for instance the small Rab GTPases Rab5C and Rab14. Rab14 is known to modulate traffic between the Golgi and endosomes (50–52) and Rab5 plays a key role in the early endosome and phagosome maturation (50). Both have previously been shown to be essential for intracellular replication of STM in epithelial cells and phagocytic cells (53, 54), which is further supported by our proteomic surveys.

In our studies, we also found conserved trafficking routes whose functions were previously only analyzed in epithelial cells. Examples include proteins of the retromer-mediated protein sorting system (Vps35), which controls the endosome to Golgi retrieval pathway, the COPI-mediated transport (α/β/β2/δ/ε/γ1-COP), which is responsible for vesicle transport between cis-Golgi back to the ER, the endosomal-lysosomal trafficking via Arf GTPase Arl8B and the clathrin-mediated endocytosis facilitated via adapter protein complex 2 (Ap2B1).

The manipulation of these routes seems to confer diverse benefits to the STM infection process, though their impact is only partially understood. Manipulation of the retromer or endolysomal system for example, affects PCC dynamics by enhancing PCC growth as well as allow its migration to the cell periphery and promoting cell-to-cell spread of the bacterium (39, 40, 55). However, at least in epithelial cells it is still disputed whether these mechanisms are essential for intracellular survival (39, 56). Likewise, by influencing COPI transport and clathrin- and adapter-mediated endocytosis, STM can enhance effector protein translocation and reduce cellular antigen presentation, respectively (57, 58). The relevance of these systems has, to the best of our knowledge, not been studied in macrophages. Because in our study we found these marker proteins to be present in STM-infected HeLa as well as RAW cells, it is likely that they play similar roles in both host cell types.

We also identified differences in the endosomal contribution to PCC formation in dependence on the infected cell line. Based on our proteome and microscopy data, some SMM elements that were canonical in STM appear to be specific to endothelial cells and seem to be less relevant in macrophages. For instance, the PCC of HeLa cells showed accumulation of small GTPases Rab2A and Rab11 (16, 31), whereas they were absent in the SMM proteome as well as during live cell imaging of infected RAW cells. Both GTPases are known key players of protein recycling. Rab2A associates with the vesicular tubular clusters and sorts anterograde-directed cargo from recycling proteins to the ER (59). Rab11 regulates early trafficking into recycling endosomes (60). Targeting these Rab GTPases is essential for intracellular replication for other intracellular bacteria such as Brucella (61) or Chlamydia (62), respectively. However, limited studies in STM indicate this may not be the case for STM (43). Even if they are relevant for STM in HeLa cells, our data suggest that they do not appear to play a role within the mature PCC in RAW cells.

More information is available on the role of the GTPase Sar1A, which was also found to be a target for STM in HeLa, but not in RAW cells. Sar1A is a key regulator of the COPII transport (63) and it was shown earlier that COPII complexes accumulate on the early SCV membrane in HeLa cells (17). These COPII complexes destabilized the SCV membrane through an unknown mechanism, permitting STM to escape the SCV and hyper-replicate within the cytosol of epithelial cells. The absence of Sar1A at the PCCs of infected macrophages could stabilize the PCC and thereby explain the lack of cytosolic persistence of STM in this cell line. Consequently, COPII-mediated interactions may be a factor determining whether STM persist stably in the PCC or establishes a population in the host cell cytosol.

We also observed several trafficking markers that were only present at the PCC of macrophages. For instance, Rab8 and Rab18 were detected at the PCC of macrophages in this study but were absent at the PCC in HeLa cells (16). Similar observations were made by Smith et al. (31) who found both Rab GTPases recruited to the early SCV (60 min p.i.) in macrophages, but not in HeLa cells. Our study therefore indicates that this difference persists late into the mature PCC. Both GTPases are suggested to allow the STM PCC to maintain early endosomal characteristics and thereby enable persistence in the SCV (28, 47, 64). We furthermore could show that disruption of both GTPases led to slightly increased intracellular proliferation of STM indicating that these GTPase might be part of host cell mechanisms that control proliferation of intracellular STM. Often these systems are involved in phagosomal maturation (such as e.g. Rab32). This restriction seems to be relieved by inhibition of the function of Rab8 and Rab18 as molecular switch. It is not certain why this mechanism is not required in HeLa cells, but there are regulatory differences of both Rab GTPases between epithelial and phagocytic cells (65) that may be a contributing factor.

Another interesting observation involves the origin of the redirected host components. In both SMM proteomes, we detected endosomal, lysosomal, Golgi, ER, mitochondrial and nuclear membrane proteins, indicating an intriguing complexity of pathogenic interactions with these host organelles. In STM the role of mitochondrial proteins and ER components at the PCC is underexplored, which contrasts with several other intracellular pathogens such as Legionella, Mycobacteria, Simkania and Chlamydia (45, 66–68). For instance, the vacuole of Legionella pneumophila is known to fuse with ER-derived secretory vesicles, associate with mitochondria, and later interact with ER membranes (69, 70). Chlamydia recruits exocytic vesicles, ER-derived lipid droplets and forms tight connections with mitochondria (71, 72). Moreover, Chlamydia caviae uses mitochondrial transporters to translocate its effector proteins directly inside mitochondria to stimulate its vacuole biogenesis and generate infectious bacterial progeny (73). Other pathogens like the protozoan parasite Encephalitozoon cuniculi cluster their replicative compartments over mitochondrial porins to scavenge ATP directly from the host (74). Considering that a direct interaction with these host organelles and compartments is crucial in a diverse group of intracellular pathogens, it is intriguing to speculate about a similar but unrecognized role for STM. The proteomic comparison of HeLa and RAW SMM proteomes provides some tentative support for this notion. In both studies, we observed that the mature PCC maintains close contact with mitochondria. We further observed the presence of the mitochondrial protein Trap1 in the SMM proteome of both host cell lines. Trap1 is a member of the HSP90 family which controls a variety of physiological functions, including cell proliferation, differentiation, and cellular survival. It is best known for its anti-apoptotic role (75, 76), but it has not been investigated further in Salmonella infections yet. We further observed several ER proteins as part of the SMM proteome, such as the dolichyl-diphosphooligosaccharide-protein glycosyltransferase subunit 2 (Rpn2), which is part of the proteasome complex at the ER. Rpn2 interacts with Trap1 (75) and assists in refolding of damaged proteins to prevent apoptosis (77). Other ER proteins found to be conserved in the SMM of RAW and HeLa cells include the vesicle-membrane-protein-associated protein A (VapA) and the transmembrane emp24 domain-containing protein 10 (Tmed10). Tmed10 assists in Golgi-ER trafficking and was observed to be exploited by cytomegalovirus to delay immune recognition (78). The integral ER protein VapA participates in establishing ER contacts with multiple membranes by interacting with different tethers. Furthermore, it was recently shown that depletion of VapA impairs autophagosome biogenesis (79). Together the data might suggest that STM interacts with ER and mitochondrial components in order to modulate and delay host functions such as apoptotic or immune responses. However, further studies are required to validate these functions.

Yet, despite these overarching similarities in the utilization of host organelles, it appears that STM also targets different sub-elements of these organelles, depending on the host cell type. For instance, in our data set we detected mitochondrial and ER proteins that appear to be specific to colonization of macrophages. Examples include the mitochondrial protein Aifm1, which is involved in regulation of apoptosis, as well as the ER proteins Sec22b and Sec61β. Intriguingly, Sec22b and Sec61β were also found to be important for other intracellular pathogens during infection of macrophages. In Legionella Sec22b partakes in the biogenesis of the Legionella-containing vacuole (80, 81). Additionally, manipulation of Sec22b was also essential for the formation of the parasitophorous vacuoles of the intracellular parasites Leishmania pifanoi and L. donovani (82, 83), indicating that the manipulation of antero- and retrograde transport between ER and Golgi may be a common target for the infection of macrophages by pathogens. Sec61β controls protein transport into the ER and was identified as part of Legionella- as well as the Brucella-containing vacuole in macrophages (68, 84). For these bacteria, interaction with Sec61β was associated with the avoidance of macrophagosomal killing of the pathogen. Overall, there is increasing evidence that intracellular pathogens, including Salmonella, target conserved as well as macrophage-specific pathways that are not utilized to the same degree in other cell lines.

In summary, this study provides compelling insights into the maturation and maintenance of the PCC of STM inside murine macrophages and highlights cell type-specific adaptation of its niche host cells. The data revealed not only common host traffic routes usurped by the pathogen, but also the selective retention of specific Rab proteins and divergent acquisition strategies of ER proteins by re-routing of ER trafficking in HeLa cells and ER mediated phagocytosis in macrophages. Furthermore, the study opens numerous targets for future investigations to elucidate cell type-specific adaptations.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Spectral data are available at the PeptideAtlas deposit (PASS01384 and PASS01470; www.peptideatlas.org/).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Nathalie Böhles, Wilrun Mittelstädt, Mahsa Wallrabenstein, Janina Noster, Stefan Walter, Monika Nietschke, Ursula Krehe and Jörg Deiwick for support and excellent technical assistance.

Footnotes

* The work was supported by grants HE1964/18-1 and 18-2 within Priority Program SPP1580, SFB 944, Z project of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, NSERC and the Niedersächsisches Ministerium für Wissenschaft und Kultur, and the The Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) project 031L0122 IntraBacWall in the InfectERA framework. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article contains supplemental Figures and Tables.

This article contains supplemental Figures and Tables.

1 The abbreviations used are:

- SCV

- Salmonella-containing vacuole

- CLSM

- confocal laser-scanning microscopy

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- LC

- liquid chromatography

- MTOC

- microtubule-organizing center

- MS/MS

- tandem mass spectrometry

- PCC

- pathogen-containing compartment

- SIF

- Salmonella-induced filaments

- SMM

- Salmonella-modified membranes

- SPI

- Salmonella pathogenicity island

- T3SS

- type III secretion system.

REFERENCES

- 1. Alonso A., and Garcia-del Portillo F. (2004) Hijacking of eukaryotic functions by intracellular bacterial pathogens. Int. Microbiol. 7, 181–191 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Holden D. W. (2002) Trafficking of the Salmonella vacuole in macrophages. Traffic 3, 161–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Majowicz S. E., Musto J., Scallan E., Angulo F. J., Kirk M., O'Brien S. J., Jones T. F., Fazil A., Hoekstra R. M., and International Collaboration on Enteric Disease 'Burden of Illness, S. (2010) The global burden of nontyphoidal Salmonella gastroenteritis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 50, 882–889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Feasey N. A., Dougan G., Kingsley R. A., Heyderman R. S., and Gordon M. A. (2012) Invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella disease: an emerging and neglected tropical disease in Africa. Lancet 379, 2489–2499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Malik-Kale P., Jolly C. E., Lathrop S., Winfree S., Luterbach C., and Steele-Mortimer O. (2011) Salmonella - at home in the host cell. Front. Microbiol. 2, 125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. LaRock D. L., Chaudhary A., and Miller S. I. (2015) Salmonellae interactions with host processes. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 13, 191–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Haraga A., Ohlson M. B., and Miller S. I. (2008) Salmonellae interplay with host cells. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6, 53–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Figueira R., and Holden D. W. (2012) Functions of the Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 (SPI-2) type III secretion system effectors. Microbiology 158, 1147–1161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Garcia-del Portillo F., Zwick M. B., Leung K. Y., and Finlay B. B. (1993) Salmonella induces the formation of filamentous structures containing lysosomal membrane glycoproteins in epithelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 10544–10548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Krieger V., Liebl D., Zhang Y., Rajashekar R., Chlanda P., Giesker K., Chikkaballi D., and Hensel M. (2014) Reorganization of the endosomal system in Salmonella-infected cells: the ultrastructure of Salmonella-induced tubular compartments. PLoS Pathog. 10, e1004374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McGhie E. J., Brawn L. C., Hume P. J., Humphreys D., and Koronakis V. (2009) Salmonella takes control: effector-driven manipulation of the host. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 12, 117–124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kuhle V., and Hensel M. (2004) Cellular microbiology of intracellular Salmonella enterica: functions of the type III secretion system encoded by Salmonella pathogenicity island 2. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 61, 2812–2826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schroeder N., Mota L. J., and Meresse S. (2011) Salmonella-induced tubular networks. Trends Microbiol. 19, 268–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Liss V., and Hensel M. (2015) Take the tube: remodelling of the endosomal system by intracellular Salmonella enterica. Cell Microbiol. 17, 639–647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Knuff K., and Finlay B. B. (2017) What the SIF is happening-The role of intracellular Salmonella-induced filaments. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 7, 335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vorwerk S., Krieger V., Deiwick J., Hensel M., and Hansmeier N. (2015) Proteomes of host cell membranes modified by intracellular activities of Salmonella enterica. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 14, 81–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Santos J. C., Duchateau M., Fredlund J., Weiner A., Mallet A., Schmitt C., Matondo M., Hourdel V., Chamot-Rooke J., and Enninga J. (2015) The COPII complex and lysosomal VAMP7 determine intracellular Salmonella localization and growth. Cell Microbiol. 17, 1699–1720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Brumell J. H., Tang P., Mills S. D., and Finlay B. B. (2001) Characterization of Salmonella-induced filaments (Sifs) reveals a delayed interaction between Salmonella-containing vacuoles and late endocytic compartments. Traffic 2, 643–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Buckner M. M., Croxen M. A., Arena E. T., and Finlay B. B. (2011) A comprehensive study of the contribution of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium SPI2 effectors to bacterial colonization, survival, and replication in typhoid fever, macrophage, and epithelial cell infection models. Virulence 2, 208–216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. McQuate S. E., Young A. M., Silva-Herzog E., Bunker E., Hernandez M., de Chaumont F., Liu X., Detweiler C. S., and Palmer A. E. (2017) Long-term live-cell imaging reveals new roles for Salmonella effector proteins SseG and SteA. Cell Microbiol. 19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Imami K., Bhavsar A. P., Yu H., Brown N. F., Rogers L. D., Finlay B. B., and Foster L. J. (2013) Global impact of Salmonella pathogenicity island 2-secreted effectors on the host phosphoproteome. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 12, 1632–1643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Malik-Kale P., Winfree S., and Steele-Mortimer O. (2012) The bimodal lifestyle of intracellular Salmonella in epithelial cells: replication in the cytosol obscures defects in vacuolar replication. PLoS ONE 7, e38732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Knodler L. A., Nair V., and Steele-Mortimer O. (2014) Quantitative assessment of cytosolic Salmonella in epithelial cells. PLoS ONE 9, e84681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Knodler L. A. (2015) Salmonella enterica: living a double life in epithelial cells. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 23, 23–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Beuzon C. R., Salcedo S. P., and Holden D. W. (2002) Growth and killing of a Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium sifA mutant strain in the cytosol of different host cell lines. Microbiology 148, 2705–2715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Thurston T. L., Matthews S. A., Jennings E., Alix E., Shao F., Shenoy A. R., Birrell M. A., and Holden D. W. (2016) Growth inhibition of cytosolic Salmonella by caspase-1 and caspase-11 precedes host cell death. Nat. Commun. 7, 13292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Castanheira S., and Garcia-Del Portillo F. (2017) Salmonella populations inside cost Cells. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 7, 432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hashim S., Mukherjee K., Raje M., Basu S. K., and Mukhopadhyay A. (2000) Live Salmonella modulate expression of Rab proteins to persist in a specialized compartment and escape transport to lysosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 16281–16288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mukherjee K., Siddiqi S. A., Hashim S., Raje M., Basu S. K., and Mukhopadhyay A. (2000) Live Salmonella recruits N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive fusion protein on phagosomal membrane and promotes fusion with early endosome. J. Cell Biol. 148, 741–753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mukherjee K., Parashuraman S., Raje M., and Mukhopadhyay A. (2001) SopE acts as an Rab5-specific nucleotide exchange factor and recruits non-prenylated Rab5 on Salmonella-containing phagosomes to promote fusion with early endosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 23607–23615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Smith A. C., Heo W. D., Braun V., Jiang X., Macrae C., Casanova J. E., Scidmore M. A., Grinstein S., Meyer T., and Brumell J. H. (2007) A network of Rab GTPases controls phagosome maturation and is modulated by Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Cell Biol. 176, 263–268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ilyas B., Tsai C. N., and Coombes B. K. (2017) Evolution of Salmonella-host cell interactions through a dynamic bacterial genome. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 7, 428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Müller P., Chikkaballi D., and Hensel M. (2012) Functional dissection of SseF, a membrane-integral effector protein of intracellular Salmonella enterica. PLoS ONE 7, e35004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chao T. C., Kalinowski J., Nyalwidhe J., and Hansmeier N. (2010) Comprehensive proteome profiling of the Fe(III)-reducing myxobacterium Anaeromyxobacter dehalogenans 2CP-C during growth with fumarate and ferric citrate. Proteomics 10, 1673–1684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Taylor G. K., and Goodlett D. R. (2005) Rules governing protein identification by mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 19, 3420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dimmer E. C., Huntley R. P., Alam-Faruque Y., Sawford T., O'Donovan C., Martin M. J., Bely B., Browne P., Mun Chan W., Eberhardt R., Gardner M., Laiho K., Legge D., Magrane M., Pichler K., Poggioli D., Sehra H., Auchincloss A., Axelsen K., Blatter M. C., Boutet E., Braconi-Quintaje S., Breuza L., Bridge A., Coudert E., Estreicher A., Famiglietti L., Ferro-Rojas S., Feuermann M., Gos A., Gruaz-Gumowski N., Hinz U., Hulo C., James J., Jimenez S., Jungo F., Keller G., Lemercier P., Lieberherr D., Masson P., Moinat M., Pedruzzi I., Poux S., Rivoire C., Roechert B., Schneider M., Stutz A., Sundaram S., Tognolli M., Bougueleret L., Argoud-Puy G., Cusin I., Duek-Roggli P., Xenarios I., and Apweiler R. (2012) The UniProt-GO Annotation database in 2011. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D565–D570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mi H., Muruganujan A., Casagrande J. T., and Thomas P. D. (2013) Large-scale gene function analysis with the PANTHER classification system. Nat. Protoc. 8, 1551–1566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Eppig J. T., Richardson J. E., Kadin J. A., Ringwald M., Blake J. A., and Bult C. J. (2015) Mouse Genome Informatics (MGI): reflecting on 25 years. Mamm. Genome 26, 272–284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kaniuk N. A., Canadien V., Bagshaw R. D., Bakowski M., Braun V., Landekic M., Mitra S., Huang J., Heo W. D., Meyer T., Pelletier L., Andrews-Polymenis H., McClelland M., Pawson T., Grinstein S., and Brumell J. H. (2011) Salmonella exploits Arl8B-directed kinesin activity to promote endosome tubulation and cell-to-cell transfer. Cell Microbiol. 13, 1812–1823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Drecktrah D., Knodler L. A., Howe D., and Steele-Mortimer O. (2007) Salmonella trafficking is defined by continuous dynamic interactions with the endolysosomal system. Traffic 8, 212–225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Garcia-del Portillo F., and Finlay B. B. (1995) Targeting of Salmonella typhimurium to vesicles containing lysosomal membrane glycoproteins bypasses compartments with mannose 6-phosphate receptors. J. Cell Biol. 129, 81–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rathman M., Sjaastad M. D., and Falkow S. (1996) Acidification of phagosomes containing Salmonella typhimurium in murine macrophages. Infect. Immun. 64, 2765–2773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Smith A. C., Cirulis J. T., Casanova J. E., Scidmore M. A., and Brumell J. H. (2005) Interaction of the Salmonella-containing vacuole with the endocytic recycling system. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 24634–24641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Steele-Mortimer O., Meresse S., Gorvel J. P., Toh B. H., and Finlay B. B. (1999) Biogenesis of Salmonella typhimurium-containing vacuoles in epithelial cells involves interactions with the early endocytic pathway. Cell Microbiol. 1, 33–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Herweg J. A., Hansmeier N., Otto A., Geffken A. C., Subbarayal P., Prusty B. K., Becher D., Hensel M., Schaible U. E., Rudel T., and Hilbi H. (2015) Purification and proteomics of pathogen-modified vacuoles and membranes. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 5, 48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Santos R. L., and Bäumler A. J. (2004) Cell tropism of Salmonella enterica. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 294, 225–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Knodler L. A., and Steele-Mortimer O. (2003) Taking possession: biogenesis of the Salmonella-containing vacuole. Traffic 4, 587–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sherwood R. K., and Roy C. R. (2013) A Rab-centric perspective of bacterial pathogen-occupied vacuoles. Cell Host Microbe 14, 256–268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Schwartz S. L., Cao C., Pylypenko O., Rak A., and Wandinger-Ness A. (2007) Rab GTPases at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 120, 3905–3910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bucci C., Lutcke A., Steele-Mortimer O., Olkkonen V. M., Dupree P., Chiariello M., Bruni C. B., Simons K., and Zerial M. (1995) Co-operative regulation of endocytosis by three Rab5 isoforms. FEBS Lett. 366, 65–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Junutula J. R., De Maziere A. M., Peden A. A., Ervin K. E., Advani R. J., van Dijk S. M., Klumperman J., and Scheller R. H. (2004) Rab14 is involved in membrane trafficking between the Golgi complex and endosomes. Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 2218–2229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Okai B., Lyall N., Gow N. A., Bain J. M., and Erwig L. P. (2015) Rab14 regulates maturation of macrophage phagosomes containing the fungal pathogen Candida albicans and outcome of the host-pathogen interaction. Infect. Immun. 83, 1523–1535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kuijl C., Pilli M., Alahari S. K., Janssen H., Khoo P. S., Ervin K. E., Calero M., Jonnalagadda S., Scheller R. H., Neefjes J., and Junutula J. R. (2013) Rac and Rab GTPases dual effector Nischarin regulates vesicle maturation to facilitate survival of intracellular bacteria. EMBO J. 32, 713–727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Brumell J. H., Tang P., Zaharik M. L., and Finlay B. B. (2002) Disruption of the Salmonella-containing vacuole leads to increased replication of Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium in the cytosol of epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 70, 3264–3270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Braun V., Wong A., Landekic M., Hong W. J., Grinstein S., and Brumell J. H. (2010) Sorting nexin 3 (SNX3) is a component of a tubular endosomal network induced by Salmonella and involved in maturation of the Salmonella-containing vacuole. Cell Microbiol. 12, 1352–1367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sindhwani A., Arya S. B., Kaur H., Jagga D., Tuli A., and Sharma M. (2017) Salmonella exploits the host endolysosomal tethering factor HOPS complex to promote its intravacuolar replication. PLoS Pathog. 13, e1006700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Misselwitz B., Dilling S., Vonaesch P., Sacher R., Snijder B., Schlumberger M., Rout S., Stark M., von Mering C., Pelkmans L., and Hardt W. D. (2011) RNAi screen of Salmonella invasion shows role of COPI in membrane targeting of cholesterol and Cdc42. Mol. Syst. Biol. 7, 474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Lapaque N., Hutchinson J. L., Jones D. C., Meresse S., Holden D. W., Trowsdale J., and Kelly A. P. (2009) Salmonella regulates polyubiquitination and surface expression of MHC class II antigens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 14052–14057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Tisdale E. J., Azizi F., and Artalejo C. R. (2009) Rab2 utilizes glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase and protein kinase Ci to associate with microtubules and to recruit dynein. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 5876–5884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Schafer J. C., McRae R. E., Manning E. H., Lapierre L. A., and Goldenring J. R. (2016) Rab11-FIP1A regulates early trafficking into the recycling endosomes. Exp. Cell Res. 340, 259–273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. de Bolle X., Letesson J. J., and Gorvel J. P. (2012) Small GTPases and Brucella entry into the endoplasmic reticulum. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 40, 1348–1352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Rejman Lipinski A., Heymann J., Meissner C., Karlas A., Brinkmann V., Meyer T. F., and Heuer D. (2009) Rab6 and Rab11 regulate Chlamydia trachomatis development and golgin-84-dependent Golgi fragmentation. PLoS Pathog. 5, e1000615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Bonifacino J. S., and Glick B. S. (2004) The mechanisms of vesicle budding and fusion. Cell 116, 153–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. del Toro D., Alberch J., Lazaro-Dieguez F., Martin-Ibanez R., Xifro X., Egea G., and Canals J. M. (2009) Mutant huntingtin impairs post-Golgi trafficking to lysosomes by delocalizing optineurin/Rab8 complex from the Golgi apparatus. Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 1478–1492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Hattula K., Furuhjelm J., Tikkanen J., Tanhuanpaa K., Laakkonen P., and Peranen J. (2006) Characterization of the Rab8-specific membrane traffic route linked to protrusion formation. J. Cell Sci. 119, 4866–4877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Finsel I., and Hilbi H. (2015) Formation of a pathogen vacuole according to Legionella pneumophila: how to kill one bird with many stones. Cell Microbiol. 17, 935–950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Escoll P., Mondino S., Rolando M., and Buchrieser C. (2016) Targeting of host organelles by pathogenic bacteria: a sophisticated subversion strategy. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 14, 5–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Schmolders J., Manske C., Otto A., Hoffmann C., Steiner B., Welin A., Becher D., and Hilbi H. (2017) Comparative proteomics of purified pathogen vacuoles correlates intracellular replication of Legionella pneumophila with the small GTPase Ras-related protein 1 (Rap1). Mol. Cell. Proteomics 16, 622–641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Isaac D. T., and Isberg R. (2014) Master manipulators: an update on Legionella pneumophila Icm/Dot translocated substrates and their host targets. Future Microbiol. 9, 343–359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Prashar A., and Terebiznik M. R. (2015) Legionella pneumophila: homeward bound away from the phagosome. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 23, 86–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Elwell C. A., and Engel J. N. (2012) Lipid acquisition by intracellular Chlamydiae. Cell Microbiol. 14, 1010–1018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Saka H. A., and Valdivia R. H. (2010) Acquisition of nutrients by Chlamydiae: unique challenges of living in an intracellular compartment. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 13, 4–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Mirrashidi K. M., Elwell C. A., Verschueren E., Johnson J. R., Frando A., Von Dollen J., Rosenberg O., Gulbahce N., Jang G., Johnson T., Jager S., Gopalakrishnan A. M., Sherry J., Dunn J. D., Olive A., Penn B., Shales M., Cox J. S., Starnbach M. N., Derre I., Valdivia R., Krogan N. J., and Engel J. (2015) Global mapping of the inc-human interactome reveals that retromer restricts Chlamydia infection. Cell Host Microbe 18, 109–121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Hacker C., Howell M., Bhella D., and Lucocq J. (2014) Strategies for maximizing ATP supply in the microsporidian Encephalitozoon cuniculi: direct binding of mitochondria to the parasitophorous vacuole and clustering of the mitochondrial porin VDAC. Cell Microbiol. 16, 565–579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Im C. N. (2016) Past, present, and emerging roles of mitochondrial heat shock protein TRAP1 in the metabolism and regulation of cancer stem cells. Cell Stress Chaperones 21, 553–562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Tian X., Ma P., Sui C. G., Meng F. D., Li Y., Fu L. Y., Jiang T., Wang Y., and Jiang Y. H. (2014) Suppression of tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated protein 1 expression induces inhibition of cell proliferation and tumor growth in human esophageal cancer cells. FEBS J. 281, 2805–2819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Amoroso M. R., Matassa D. S., Laudiero G., Egorova A. V., Polishchuk R. S., Maddalena F., Piscazzi A., Paladino S., Sarnataro D., Garbi C., Landriscina M., and Esposito F. (2012) TRAP1 and the proteasome regulatory particle TBP7/Rpt3 interact in the endoplasmic reticulum and control cellular ubiquitination of specific mitochondrial proteins. Cell Death Differ. 19, 592–604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Ramnarayan V. R., Hein Z., Janssen L., Lis N., Ghanwat S., and Springer S. (2018) Cytomegalovirus gp40/m152 uses TMED10 as ER anchor to retain MHC class I. Cell Rep. 23, 3068–3077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Zhao Y. G., Liu N., Miao G., Chen Y., Zhao H., and Zhang H. (2018) The ER contact proteins VAPA/B interact with multiple autophagy proteins to modulate autophagosome biogenesis. Curr. Biol. 28, 1234–1245 e1234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Derre I., and Isberg R. R. (2004) Macrophages from mice with the restrictive Lgn1 allele exhibit multifactorial resistance to Legionella pneumophila. Infect. Immun. 72, 6221–6229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Kagan J. C., Stein M. P., Pypaert M., and Roy C. R. (2004) Legionella subvert the functions of Rab1 and Sec22b to create a replicative organelle. J. Exp. Med. 199, 1201–1211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Canton J., Ndjamen B., Hatsuzawa K., and Kima P. E. (2012) Disruption of the fusion of Leishmania parasitophorous vacuoles with ER vesicles results in the control of the infection. Cell Microbiol. 14, 937–948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Ndjamen B., Kang B. H., Hatsuzawa K., and Kima P. E. (2010) Leishmania parasitophorous vacuoles interact continuously with the host cell's endoplasmic reticulum; parasitophorous vacuoles are hybrid compartments. Cell Microbiol. 12, 1480–1494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Celli J., de Chastellier C., Franchini D. M., Pizarro-Cerda J., Moreno E., and Gorvel J. P. (2003) Brucella evades macrophage killing via VirB-dependent sustained interactions with the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Exp. Med. 198, 545–555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Spectral data are available at the PeptideAtlas deposit (PASS01384 and PASS01470; www.peptideatlas.org/).