Abstract

In this study, the effect of green synthesized sulfur nanoparticle (SNP) at different concentration (0, 0.01, 0.1, 1 and 10 mg/ml) on some physiological, phytochemical and biochemical traits of lettuce plants was investigated. For the first time, SNP were green synthesized using Cinnamomum zeylanicum barks extract. Our results indicated that the treatment of lettuce plants with 1 mg/ml of SNP improved the growth and photosynthetic parameters of lettuce plants than related control. Some other physiological parameters such as proline, glycine betaine and soluble sugars levels along with some phytochemical parameters like anthocyanin, total phenol, flavonoids and tannin contents were enhanced after treatment of the plants with same concentration of SNP. On the other hand, specific activity of antioxidant enzymes (catalase, ascorbate peroxidase and polyphenol oxidase) and stress markers level, MDA and H2O2 were reduced in the same treated lettuce plants. However, a concentration of 10 mg/ml of SNP exhibited toxicity on lettuce plants with inducing oxidative stress markers (H2O2 and MDA) and consequently reducing plant growth and biomass. This oxidative stress tend to diminish some physiological, phytochemical and biochemical parameters in treated lettuce plants. Overall, it can be concluded that the green synthesis SNP at an optimal concentration of 1 mg/ml improved physiological parameters in the lettuce plants making them potent to tolerate stressful conditions. However, higher concentration of SNP (10 mg/ml) indicated toxic effects on all of the physiological parameters.

Keywords: Sulfur nanoparticle, Lettuce plant, Green synthesis, Antioxidant enzymes

Introduction

Sulfur is one of the most important soil elements with a wide range of industrial, agricultural and pharmaceutical applications. It may be used in the production of nitrogenous fertilizers, antimicrobial agents and fungicides (Ober 2003; Ellis et al. 1998). Sulfur, as an essential element in plants, is involved in the synthesis of some biomolecules such as amino acids, coenzymes, vitamins, proteins and chlorophylls. Sulfur also plays an important role in plant resistance to diseases and abiotic stress (Dubuis et al. 2005).

In the recent years, the use of nanoparticles with controlled structure and functionality is increasing rapidly. The applications of nanoparticles (NPs) in various fields, including agriculture, biomedicines, pharmaceutics, transportation, biosensors consumer products, catalysts and industrial products, has increased in recent decades (Novack and Bucheli 2007; Roco 2003). However, the MNPs (manufactured nanoparticles) contaminate the soil, air and freshwater through wastewater, sewage sludge and landfills during their synthesis (Aziz et al. 2015; Prasad et al. 2016). Green synthesis of nanoparticles is the most appropriate way to resolve the stated problems (Shankar et al. 2018). This kind of nanoparticles synthesis can be easily performed at room temperature by plant extract and minimal facility. The effects of different nanoparticles such as TiO2NP (Gao et al. 2013), FeNP (Canivet et al. 2015), AgNP (Larue et al. 2014), CeO2 (Peralta-Videa et al. 2014; Gui et al. 2015; Zhang et al. 2017), MgNP (Indira and Tarafdar 2015) and AlNP (Juhel et al. 2011) on plant growth were previously studied. The above mentioned nanoparticles contain heavy metals such as silver (I), lead (II) and cobalt (II) that can be harmful to plants, humans and soil, while sulfur nanoparticles (SNPs) are regarded as an essential element for plant growth and normal functions. The SNPs indicate some environmental protection applications with antifungal activity and remediation of heavy metal pollutants in water (Bakry et al. 2015; Suleiman et al. 2015; Tripathia et al. 2018). On the other hand, different synthesized SNP has been used in agriculture systems as potent anti-pathogens and fertilizer. Therefore, due to the importance and different applications of this nanoparticles, developing an easy and high-quality synthesis method for sulfur nanoparticles is essential.

The present study focus on high quality synthesis of sulfur nanoparticles using Ceylon cinnamon (Cinnamomum zeylanicum) bark for the first time. We also investigate the effect of this nanoparticles on some physiological and biochemical parameters of Lettuce (Lactuca sativa) as a common model plant for evaluation of its possible harmless effects or benefits on crop plants.

Materials and methods

Preparation of aqueous extract of C. zeylanicum barks

C. zeylanicum barks were washed several times with distilled water to remove the dust particles and then dried. Dried powder of C. zeylanicum barks (40 g) boiled with 400 ml of sterile distilled water in 500 ml glass beaker for 10 min. After boiling, the yellow extract obtained was cooled at room temperature. Then, the plant extract was filtered using a filter paper (Whitman No. 1), followed by centrifugation at 2000 rpm for 15 min. The extract of C. zeylanicum barks was stored at room temperature until synthesis of sulfur nanoparticles.

Synthesis of sulfur nanoparticles

In order to obtain sulfur nanoparticles, sodium thiosulfate (Na2S2O3, 5 g) was added to the extract of C. zeylanicum barks (100 ml) under stirring for 15 min at room temperature and then diluted to 100 ml by sterile distilled water. For uniform precipitations of sulfur, hydrochloric acid (HCl, 32%) was added drop by drop to the solution under mild stirring. After centrifugation at 5000 rpm for 10 min and discarding the supernatant, the precipitates were washed several times with absolute ethanol and distilled water. The purified sulfur nanoparticles were dried in a vacuum at 50 °C centigrade for 5 h. The product appeared as a light yellow powder that were analyzed by SEM, FTIR and XRD.

Sulfur and sulfonic acid are obtained through a disproportionation reaction in the C. zeylanicumbarks extract, sodium thiosulfate and acidic solution according to the following formula:

Plant materials, growth conditions and treatments

The lettuce seeds after surface sterilized were pretreated with different concentration of sulfur nanoparticles (0, 0.001, 0.01, 1 and 10 mg/ml) in petri dish, then germinated in pots containing autoclaved soil and sand mixture (1:2). The pots were kept in a greenhouse, with 14/8 h light/dark cycles under 25/18 °C temperature. Each pot was thinned to one seedling per pot. The seedlings were irrigated every alternate day with distilled water. A Hoagland solution (half strength) was used once a week to feed the pots. After 6 weeks, pots were harvested and stored in the freezer (− 80) for measuring biological traits.

Measurement of growth parameters

After sterilization, lettuce seeds were immersed in different concentrations of SNP for 2 h. A filter paper was inserted into a 100 mm × 15 mm Petri dish, and 5 ml of the each test solution was added. Seeds were added onto the filter paper, with 10 seeds per dish. Germination percentage was calculated by counting the number of germinated seeds after 8 days. Total fresh weight, root and shoot length, length and width of leaf in 7 leafed lettuce seedlings were measured immediately after removal from the pots.

Measurment of physiological parameters

Photosynthetic parameters

Relative chlorophyll content (SPAD chlorophyll) and chlorophyll fluorescence parameters were subjected to measure by a chlorophyll meter (CL-01model, Hansatech instrument, UK) and Chlorophyll Fluorimeter (PEA model, Hansatech instrument, UK), respectively. Photosynthetic pigments i.e. Chl a, Chl b and carotenoids were evaluated based on Arnon (1949) method. In this regard, acetone (80%) extract of samples were centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was subjected to measuring of absorbance at 663, 645, and 470 nm to identify pigments content (mg/g FW).

The Qubit Systems’ S104 Differential O2 Analyzer (DOX) was used to measure the photosynthetic O2 evolution. The chamber was calibrated using nitrogen gas and then oxygen (O2) was added to 21%. Leaf samples were placed into the chamber and ambient air was injected. The released oxygen from leaves was measured by the device sensor for1000 s. The light was set at 66 µmol/m2/s1.

Estimation of stress markers

The Content of MDA were calculated using the thiobarbituric acid (TBA) method and extinction coefficient of 155 mM−1/cm1 according to Heath and Packer (1968) method. H2O2 contents was measured using Velikova et al. (2000) protocol. The fresh leaves of samples were homogenized with trichloroacetic acid 1% (w/v) and centrifugation at 12,000g (10 min), the absorbance of the reaction solution (KI 1 M (1 mL) + potassium phosphate buffer 10 mM (0.5 mL, pH 7.0) + supernatant (0.5 mL)) was recorded at 320 nm (Varian, Carry 300, United States). According to Brand-Williams et al. (1995), the activity of free radical scavenging was calculated by stable 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical at 517 nm.

Measurement of compatible solutes

The protocols of Bates et al. (1973) and Grieve and Grattan (1983) were used to measure contents of proline and glycine betaine, respectively. The plants proline and glycine betaine levels were calculated using the calibration curve and expressed as μmol proline g−1 fresh weight (FW) and μg/mg DW, respectively. In order to measure total soluble sugar, the methanolic phase of the fresh tissue was used. The protocols of Irigoyen et al. (1992) were used to measure contents of proline and total soluble sugar, respectively.

Measurment of phytochemical parameters

The total phenolic contents were estimated according to the method of Folin–Ciocalteu reagent. The absorbance of the reaction solution (Folin–Ciocalteu reagent, Na2CO3 (7%) and plant methanol extract) was recorded at 725 nm after incubation in dark (25 °C, 1 h), and calculated as mg gallic acid equivalent/g DW. The flavonoid contents were measured according to the method of Zhishen et al. (1999) and expressed as mg catechin equivalent/g DW.

The content of anthocyanin was measured according to Sims and Gamon (2002) method. The methods of Shamsa et al. (2008) and Broadhurst and Jones (1978) were used to determinate contents of total alkaloid and tannin, respectively. The concentration of total alkaloid and tannin were expressed as mg of atropine equivalents per g of DW and g E. Catechin. 100 g−1DM.

Measurment of biochemical parameters

Estimation of enzymes activity

To extract the soluble protein, the fresh leaves were homogenized in phosphate buffer (pH 7.8) with 0.5% of PEG (polyethylene glycol) 4000, 0.1 mM EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid), 1% of PVP (polyvinylpyrrolidone) and 2 mM dithiothreitol. Total protein was measured according to Bradford (1976) method using bovine serum albumin as standard. By determining the decrease in absorbance of H2O2 at 240 nm, the activity of CAT enzyme was calculated based on Bailly et al. (1996). By determining the decrease in absorbance at 290 nm during time, the activity of APX enzyme was calculated according to Nakano and Asada (1981). Protease activity was evaluated based on Penner and Aston (1969) method through casein reduction after the proteolytic activity of enzyme extraction. Polyphenol oxidase activity were measured according to Raymond et al. (1993) method.

Free amino acid extraction

The protocols of Hwang and Ederer (1975) were used to measure concentration of free amino acid. The content was determined using glycine standard curve and expressed as mg/g. FW.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were repeated three times and each mean was calculated from three independent replicates. Statistical analysis of the results was performed using SAS 9.1.3 software (SAS Institute, Inc., SAS Campus Drive, Cary, NC, USA) and the mean comparison was done using Duncan’s multiple range test at the P ≤ 0.05 level of significance.

Results

Growth parameters

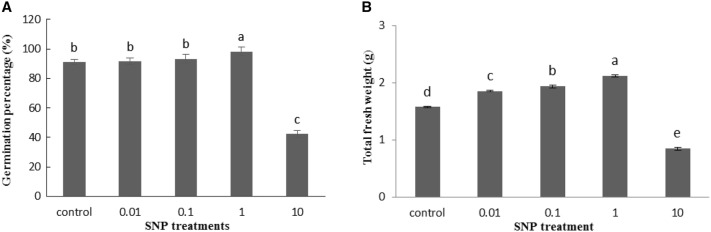

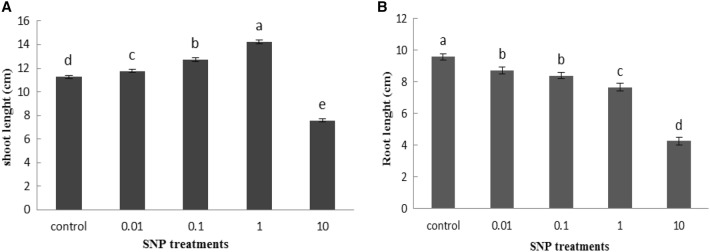

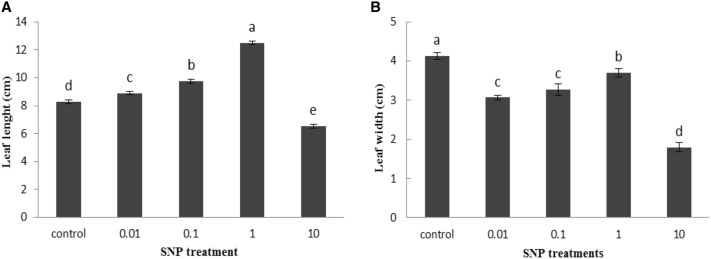

Our results indicated that SNP treatment at the concentration of 1 mg/ml significantly increased lettuce seed germination percentage by 8% compared to control group. However, the concentration of SNP as 10 mg/ml displayed toxicity on the seed germination and declined germination approximately 50% than control sample (Fig. 1a). The fresh weight of all lettuce seedlings significantly improved at 0.01, 0.1 and 1 mg/ml of SNP treatments by 17.5, 22.8 and 34.3%, respectively, but reduced at higher level (10 mg/ml) by 46.3% compared to related controls (Fig. 1b). The results clearly showed a rise in the seedlings shoots length in a dose dependent manner of SNP. At the concentration of 10 mg/ml, the toxic effects of SNP appeared and the shoot length was significantly decreased compared with control ones (Fig. 2a). On the other hand, analysis of data showed a gradual decrease in the plant root length responded to increased SNP concentrations compared to the untreated plants. The highest decrease in root length was observed at 10 mg/ml of SNP by 55.6% (Fig. 2b). An increasing trend was observed in leaf length with increasing SNP concentration, as well as, with the highest increase recorded by 51% at 1 mg/ml SNP compared with control. However, the leaf length was significantly decreased at 10 mg/ml of SNP than control plants (Fig. 3a). Treatment of different concentrations of SNP reduced leaf lettuce width compared with the control group and the highest reduction was obtained at 10 mg/ml of SNP as 56.5% (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 1.

Influence of SNP on seed germination percentage (a) and total fresh weight (b) of lettuce seedlings. Bars represents mean ± standard error. Means followed by the same letter are not significantly different (P < 0.05) as determined by Duncan’s multiple-range test

Fig. 2.

Influence of SNP on shoot length (a) and root length (b) of lettuce plant. Bars represents mean ± standard error. Means followed by the same letter are not significantly different (P < 0.05) as determined by Duncan’s multiple-range test

Fig. 3.

Influence of SNP on Leaf length (a) and leaf width (b) of lettuce plant. Bars represents mean ± standard error. Means followed by the same letter are not significantly different (P < 0.05) as determined by Duncan’s multiple-range test

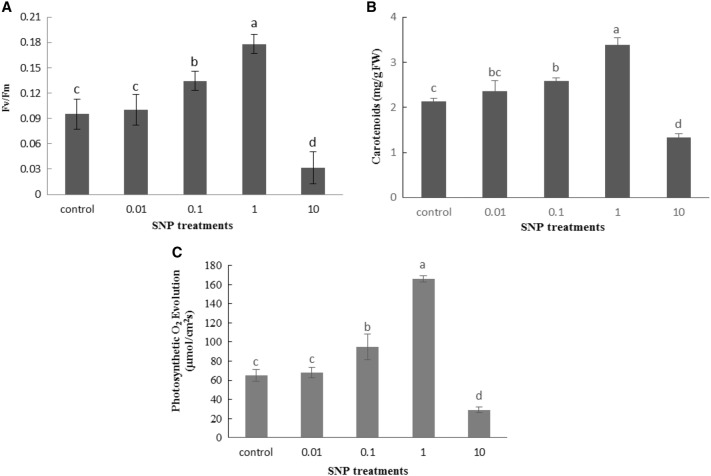

Photosynthetic parameters

The results showed that in response to different concentrations of SNP, a significant increase in the content of photosynthetic pigments (Chl a, Chl b and carotenoids), photosynthetic O2 evolution, maximum quantum efficiency of PSII (Fv/Fm) was observed. Increasing SNP concentration led to a significant enhancement in Chl a, Chl b, carotenoids, photosynthetic O2 evolution, Fv/Fm gradually up to 1 mg/ml SNP. However, the 10 mg/ml concentration of SNP significantly tend to decrease all of measured photosynthetic parameters and pigments in treated lettuce plants than control group (Figs. 4, 5).

Fig. 4.

Influence of SNP on chlorophyll a (a) and chlorophyll b (b) of lettuce plant. Bars represents mean ± standard error. Means followed by the same letter are not significantly different (P < 0.05) as determined by Duncan’s multiple-range test

Fig. 5.

Influence of SNP on Fv/Fm (a) carotenoids level (b) and photosynthetic O2 evolution (c) in lettuce plant. Bars represents mean ± standard error. Means followed by the same letter are not significantly different (P < 0.05) as determined by Duncan’s multiple-range test

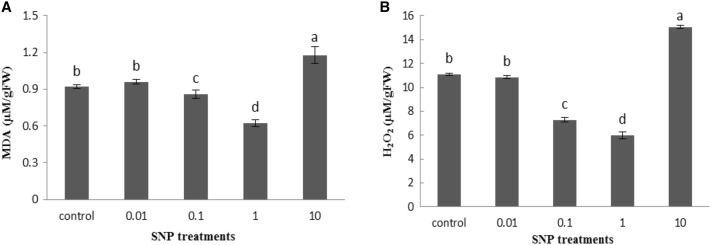

Stress markers

Increasing the concentration of SNP reduced the content of both H2O2 and MDA in the lettuce leaves, and the highest decrease was observed at 1 mg/ml concentration of SNP. The contents of H2O2 and MDA decreased by 46 and 32%, respectively, at 1 mg/ml SNP over control. However, treatment with 10 mg/ml of SNP significantly increased H2O2 and MDA contents by 35.9 and 28.2%, respectively, compared with control plants (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Influence of SNP on stress markers, malondialdehyde (a) and hydrogen peroxide level (b) in lettuce plant. Bars represents mean ± standard error. Means followed by the same letter are not significantly different (P < 0.05) as determined by Duncan’s multiple-range test

Contents of compatible solutes

Our results revealed that the proline content of lettuce plants at 0.1 mg/ml of SNP started to rise and reached to maximum at 1 mg/ml of SNP, then, decreased by 32.9% at 10 mg/ml of SNP compared to untreated plants (Fig. 7a). The SNP-treated lettuce plants exhibited a significant difference in the content of glycine betaine under different SNP levels. The lowest and highest content of the glycine betaine observed in 10 and 1 mg/ml of SNP treatments, respectively (Fig. 7b). The results also showed that soluble sugars increased by 15, 85.6 and 167% at 0.01, 0.1 and 1 mg/ml of SNP, respectively. However, it decreased at 10 mg/ml of SNP by 55% over control plants (Fig. 7c).

Fig. 7.

Influence of SNP on proline (a), glycine betaine (b) and soluble sugars (c) of lettuce plant. Bars represents mean ± standard error. Means followed by the same letter are not significantly different (P < 0.05) as determined by Duncan’s multiple-range test

Phytochemicals level

The results indicated that the SNP treatments increased the total phenol content of lettuce plants compared to the control. The highest level of phenols was seen at 1 mg/ml concentration of SNP. However, the phenol level decreased at 10 mg/ml of SNP. (Figure 8a). Whereas, the contents of flavonoids in the leaves of treated lettuce began to increase at 0.01 mg/ml of SNP and reached to maximum level at 1 mg/ml of SNP, It decreased at 10 mg/ml of SNP over control plants (Fig. 8b). On the other hand, exposure of lettuce plants to 0.01, 0.1 and 1 mg/ml SNP enhanced the tannin content by 7.6, 43.9 and 74.4% respectively, relative to the control ones. At 10 mg/ml of SNP, it decreased by 18.4% compared to the control treatments (Fig. 8c).

Fig. 8.

Influence of SNP on total phenol (a) and flavonoids (b), tannins (c), alkaloids (d) and anthocyanins (e) of lettuce plant. Bars represents mean ± standard error. Means followed by the same letter are not significantly different (P < 0.05) as determined by Duncan’s multiple-range test

It was also seen that the alkaloids content of lettuce plants at 0.1 mg/ml of SNP started to enhance and reached to maximum level at 1 mg/ml of SNP. In contrast, it decreased at 10 mg/ml compared to untreated plants (Fig. 8d).

Our results also showed that SNP treatment caused a significant increase in anthocyanin contents of lettuce plants in a dose dependent manner up to 1 mg/mL of SNP. At 10 mg/mL of SNP, anthocyanin level fall considerably than control (Fig. 8e).

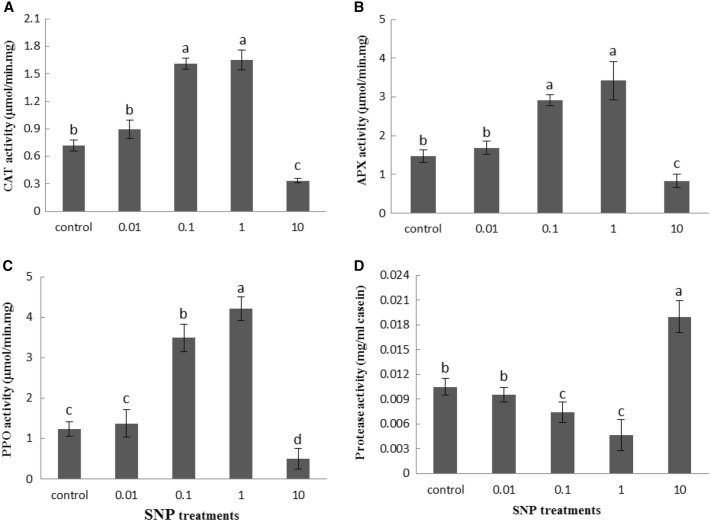

Enzymes activity and biochemical markers

The results indicated that the SNP treatments up to 1 mg/ml significantly increased total protein and free amino acid gradually compared to the control treatments. However, at 10 mg/ml of SNP, a decrease was seen compared with control (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

Influence of SNP on total proteins (a) and free amino acids (b) of lettuce plant. Bars represents mean ± standard error. Means followed by the same letter are not significantly different (P < 0.05) as determined by Duncan’s multiple-range test

It was also found that the SNP treatments increased the activity of antioxidant enzymes, CAT, APX and PPO than control treatment and reached highest level of activity at concentration of 1 mg/ml. However, the enzymes activity fall at 10 mg/ml of SNP compared with the control group. The highest increase in the activity of CAT, APX and PPO enzymes was observed at 1 mg/ml of SNP by 129.9, 131.8 and 240.4%, respectively, than control treatments (Fig. 10). It was also revealed that SNP lead to decrease in protease activity of the lettuce leaves, and the highest decrease was observed at 1 mg/ml of SNP. The protease activity decreased by 55.9% at 1 mg/ml of SNP over control. However, treatment with 10 mg/ml of SNP significantly increased protease activity by 81% compared to untreated plants (Fig. 10d).

Fig. 10.

Influence of SNP on CAT (a), APX (b), PPO (c) and Protease (d) enzymes activity of lettuce plant. Bars represents mean ± standard error. Means followed by the same letter are not significantly different (P < 0.05) as determined by Duncan’s multiple

Discussion

It is well known that Sulfur is a necessary macronutrient in plants and plays various plant functions. It indicates a lot of critical roles in metabolic processes, due to its specific importance in structure and activity of some coenzymes. Moreover, sulfur integrates in structure of some essential amino acids and metabolites (Hasanuzzaman et al. 2018). Hence, it can be responsible for many aspects of plant defense against environmental stress (Capaldi et al. 2015). Essential elements containing nanoparticles are widely used in agricultural systems due to their specific physicochemical properties, including high catalytic capabilities, ability to engineer electron exchange and high surface area to volume ratio. They can be very effective than classic fertilizers. Our results showed that application of sulfur nanoparticles at concentrations below 1 mg/ml improved all of biochemical and physiological traits of lettuce plants such as growth parameters, gas exchange, photosynthetic parameters, enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants and osmolytes. This is in accordance with the results of SNP treatments on growth of Cucurbita pepo (Salem et al. 2016a) and Solanum lycopersicum (Salem et al. 2016b). Given the role of sulfur in the structure, synthesis and function of important antioxidant systems such as glutathione, thioredoxin, glutaredoxin, sulfur amino acids and sulfur flavonoids (Teles et al. 2015; Mukwevho et al. 2014), the positive impact of SNP on lettuce plant physiology and stress tolerance could be interpreted. It was also reported that sulfur fertilizers were greatly effective in osmolyte homeostasis in some plants like maize at salinity stress condition (Riffat and Aqeel Ahmad 2018).

Recent studies have demonstrated that sulfur not only raises the productivity of plants under normal condition but also protects them from abiotic stresses like salinity, drought, and toxic/heavy metals. Different sulfur compounds apparently play antioxidant role or modulate antioxidant defense system. Among them, glutathione (GSH) is regarded as one of the strong antioxidants and stress protectants. Sulfur interactions with other biomolecules promote stress signaling to provide defense against environmental stresses. However, this element uptake, translocation, and action mechanisms in plants at stressful conditions are still under investigation. The negative effects of SNP at 10 mg/ml concentration on lettuce growth could be due to sulfur toxicity and induction of oxidative stress at high concentration of SNP.

It is obvious that the contents of photosynthetic pigments is one of the important parameters indicating photosynthesis rate and growth conditions of the plant (Ghorbani et al. 2018b). The results of photosynthetic pigments and anthocyanin measurements showed that the SNP treatment up to 1 mg/ml concentration increased all pigments compared to the control treatment. Increased photosynthetic pigments in response to nanoparticles such as silver nanoparticles (Latif et al. 2017) and iron nanoparticles (Dana et al. 2018) have also been reported. Govorov and Carmeli (2007) suggested nanoparticles can improve plant growth by increasing the efficiency of chemical energy production in the photosynthetic system. Thus, as the results showed, increasing the content of photosynthetic pigments under SNP treatments can increase the rate of photosynthesis and thereby improve plant growth and biomass production. The decrease in photosynthetic pigments at high concentrations of SNP can be due to the peroxidation of chloroplast membranes or the inactivation of pigment synthesizing enzymes in response to the oxidative stress induced at high concentrations of SNP.

The accumulation of osmolyte compounds such as proline, glycine betaine and soluble sugars is one of the most important strategies of plants to adapt to different environmental conditions. The results showed that proline, glycine betaine and soluble sugars contents increased in response to SNP treatment. Accumulation of osmolyte compounds were also observed under the treatments of ZnO (Foroutan et al. 2018), TiO2 (Mohammadi et al. 2016) and SiO2 (Karimi and Mohsenzadeh 2016) nanoparticles. Since the osmolyte compounds (proline, glycine betaine and soluble sugars) can act as a osmoprotectant, neutralizing free radicals, metal chelators, stability of macromolecules and a source of nitrogen and carbon in the plant (Ben Rejeb et al. 2014), increase in their accumulation under SNP treatment can improve plant growth.

The accumulation of phenolic compounds is another mechanism to increase adaptability and improve plant growth under adverse environmental conditions (Ghorbani et al. 2018a). The results showed that increasing the concentration of SNP significantly increased the flavonoids, phenol total and tannin contents of the lettuce plant compared to the control treatment, which is according to the results obtained from the effect of AgNPs on potato (Bagherzadeh Homaee and Ehsanpour 2015) and Arabidopsis (Nair and Chung 2014). Phenolic compounds are a large group of secondary metabolites that include phenols, flavonoids, anthocyanins, tannins and their derivatives. Phenolic compounds due to the free hydroxyl group in their structure are known as antioxidant compounds, which exhibit free radical scavenging activity (Kowalska et al. 2014). Therefore, the increased accumulation of flavonoids, total phenol and tannin under SNP treatments indicated a positive effect of this nanoparticle on antioxidant capacity of lettuce plants.

Increasing the concentration of nutrients such as sulfur, generate a variety of free radicals that cause oxidative stress in plants. It was well documented that the metalloids and heavy metals-induced oxidative stress damages the various parts of the cells, especially cell membranes, and causes the oxidation of membrane lipids (Zhang et al. 2005). The results of this study showed that the increase in the SNP concentration reduced contents of H2O2 and MDA compared to control treatment, indicating the positive role of SNP in reducing free radicals and improving plant growth conditions. However, high concentration of SNP (10 mg/ml) significantly increased H2O2 and MDA contents compared to the control treatment, demonstrating induction of oxidative stress in lettuce plants. Induction of oxidative stress at high concentrations of SNP is in accordance with the results obtained from the effect of AgNP on Arabidopsis thaliana (Nair and Chung 2014) and copper nanoparticles on Cucumis sativus plants (Mosa et al. 2018). The SNP treatment up to 1 mg/ml SNP also increased the activity of CAT, APX and PPO enzymes and decreased the activity of protease enzyme, whereas, concentration of 10 mg/ml decreased the activity of antioxidant enzymes and increased protease activity. Nair and Chung (2014), Rui et al. (2017) and Karami Mehrian et al. (2015) obtained similar results from the effect of AgNPs on rice, peanut and tomato seedlings, respectively. The CAT and APX enzymes reduced the production of hydroxyl radical by degrading hydrogen peroxide as its precursor. Hydroxyl radical as a highly reactive compound, damages important macromolecules such as DNA, bio-membranes and proteins (Ghorbani et al. 2018a). Sharma et al. (2012) showed that the application of AgNPs (high concentrations) induced oxidative stress and increased the activity of antioxidant enzymes such as CAT, APX and PPO in mustard plants. In another study, Laware and Raskar (2014) stated that high concentrations of TiO2 induced oxidative stress and, consequently, toxicity in the onion plants. The CAT enzyme plays an important role in reducing the lipid oxidation and thus retaining the membrane stability under stressful conditions. Increasing the activity of CAT and APX enzymes can play an important role in reducing the negative effects of oxidative stress under different environmental conditions. These results corroborate with the findings of Karami Mehrian et al. (2015), who indicated application of AgNPs treatments on inducing the activity of CAT and APX enzymes in tomato plants. On the other hand, reducing the activity of the CAT, APX and PPO enzymes at high concentrations of SNP (10 mg/ml) may be attributed to the inactivation of the CAT, APX and PPO enzymes by the non-specific degradation of the enzyme proteins or the production of excess reactive oxygen species.

Conclusion

In the current study, for the first time, the green synthesis of sulfur nanoparticles using Cinnamomum zeylanicum barks extract was reported. The results of the effect of different concentrations of SNP on lettuce plant showed that application of SNP in the concentrations to 1 mg/ml had a positive effect on growth and biochemical traits of lettuce. The SNP treatment at 1 mg/ml produce healthy and high quality of lettuce plant compared to untreated plants. However, the concentration of 10 mg/ml of SNP decreased the growth and biomass production and induced oxidative stress (H2O2 and MDA). It is suggested that the positive effect of SNP on lettuce growth is due to the potential nutritional value of SNP through the production of sulfur bio compounds in the plant.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Arnon DI. Copper enzymes in isolated chloroplasts. Polyphenol oxidase in Beta vulgaris. Plant Physiol. 1949;24:1–15. doi: 10.1104/pp.24.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aziz N, Faraz M, Pandey R, Shakir M, Fatma T, Varma A, Barman I, Prasad R. Facile algae-derived route to biogenic silver nanoparticles: synthesis, antibacterial, and photocatalytic properties. Langmuir. 2015;31(42):11605–11612. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.5b03081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagherzadeh Homaee M, Ehsanpour AA. Physiological and biochemical responses of potato (Solanum tuberosum) to silver nanoparticles and silver nitrate treatments under in vitro conditions. Indian J Plant Physiol. 2015;20(4):353–359. [Google Scholar]

- Bailly C, Benamar A, Corbineau F, Come D. Changes in malondialdehyde content and in superoxide dismutase, catalase, and glutathione reductase activities in sunflower seeds as related to deterioration during accelerated ageing. Physiol Plant. 1996;97:104–110. [Google Scholar]

- Bakry AB, Mervat Sadak MS, El-karamany MF. Effect of humic acid and sulfur on growth some biochemical constituents yield, and yield attributes of flax grown under newly reclaimed sandy soils. ARPN J Agric Biol Sci. 2015;10:247–259. [Google Scholar]

- Bates LS, Waldren RP, Teare ID. Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant and Soil. 1973;39(1):205–207. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Rejeb K, Abdelly C, Savoure A. How reactive oxygen species and proline face stress together. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2014;80:278–284. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand-Williams W, Cuvelier ME, Berset C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT Food Sci Technol. 1995;28:25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Broadhurst RB, Jones WT. Analysis of condensed tannins using acidified vanillin. J Sci Food Agric. 1978;48(3):788–794. [Google Scholar]

- Canivet L, Dubot P, Garcon G, Denayer FO. Effects of engineered iron nanoparticles on the bryophyte, physcomitrella patens (Hedw.) bruch & schimp, after foliar exposure. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2015;113:499–505. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2014.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi FR, Gratão PL, Reis AR, Lima LW, Azevedo RA. Sulfur metabolism and stress defense responses in plants. Tropical Plant Biol. 2015;8:60–73. [Google Scholar]

- Dana E, Taha A, Afkar E. Green synthesis of iron nanoparticles by Acacia nilotica pods extract and Its catalytic, adsorption, and antibacterial activities. Appl Sci. 2018;8:1922. [Google Scholar]

- Dubuis PH, Marazzi C, Städler E, Mauch F. Sulphur deficiency causes a reduction in antimicrobial potential and leads to increased disease susceptibility of oilseed rape. J Phytopathol. 2005;153:27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis M, Ferree D, Funt R, Madden L. effects of an apple scab-resistant cultivar on use patterns f inorganic and organic fungicides and economies of disease control. Plant Dis. 1998;82:428. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.1998.82.4.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foroutan L, Solouki M, Abdossi V, Fakheri BA. The effects of zinc oxide nanoparticles on enzymatic and osmoprotectant alternations in different Moringa peregrina Populations under drought stress. Int J Basic Sci Med. 2018;3(4):178–187. [Google Scholar]

- Gao J, Xu G, Qian H, Liu P, Zhao P, Hu Y. Effects of nano-TiO2 on photosynthetic characteristics of Ulmus elongata seedlings. Environ Pollut. 2013;176:63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2013.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghorbani A, Razavi SM, Ghasemi Omran VO, Pirdashti H. Piriformospora indica alleviates salinity by boosting redox poise and antioxidative potential of tomato. Russ J Plant Physiol. 2018;65(6):898–907. [Google Scholar]

- Ghorbani A, Razavi SM, Ghasemi Omran VO, Pirdashti H. Piriformospora indica inoculation alleviates the adverse effect of NaCl stress on growth, gas exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) Plant Biol. 2018;20(4):729–736. doi: 10.1111/plb.12717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govorov AO, Carmeli I. Hybrid structures composed of photosynthetic system and metal nanoparticles: plasmon enhancement effect. Nano Lett. 2007;7(3):620–625. doi: 10.1021/nl062528t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieve CM, Grattan SR. Rapid assay for determination of water soluble quaternary amonium compounds. Plant Soil. 1983;70:302–307. [Google Scholar]

- Gui X, Zhang Z, Liu S, Ma Y, Zhang P, He X, Li Y, Zhang J, Li H, Rui Y, Liu L, Cao W. Fate and phytotoxicity of CeO2 nanoparticles on Lettuce cultured in the potting soil environment. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(8):e0134261. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasanuzzaman M, Hossain MS, Bhuyan MHMB, Al Mahmud J, Nahar K, Fujita M (2018) The role of sulfur in plant abiotic stress tolerance: molecular interactions and defense mechanisms. In: Hasanuzzaman M, Fujita M, Oku H, Nahar K, Hawrylak-Nowak B (eds) Plant nutrients and abiotic stress tolerance. Springer, Singapore, pp 221–252

- Heath RL, Packer L. Photoperoxidation in isolated chloroplasts. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1968;125:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(68)90654-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang MN, Ederer GM. Rapid hippurate hydrolysis method for presumptive identification of group B streptococci. J Clin Microbiol. 1975;1:114–115. doi: 10.1128/jcm.1.1.114-115.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indira R, Tarafdar JC. Perspectives of biosynthesized magnesium nanoparticles in foliar application of wheat plant. J Bionanoscience. 2015;9:209–214. [Google Scholar]

- Irigoyen JJ, Einerich DW, Sanchez-Diaz M. Water stress induced changes in concentrations of proline and total soluble sugars in nodulated alfalfa (Medicago sativa) plants. Physiol Plant. 1992;84:55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Juhel G, Batisse E, Hugues Q, Daly D, van Pelt FN, O’Halloran J, Jansen M. Alumina nanoparticles enhance growth of Lemna minor. Aquat Toxicol. 2011;105:328–336. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2011.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karami Mehrian S, Heidari R, Rahmani F. Effect of silver nanoparticles on free amino acids content and antioxidant defense system of tomato plants. Indian J Plant Physiol. 2015;20(3):257–263. [Google Scholar]

- Karimi J, Mohsenzadeh S. Effects of silicon oxide nanoparticles on growth and physiology of wheat seedlings. Russ J Plant Physiol. 2016;63(1):119–123. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalska I, Pecio L, Ciesla L, Oleszek W, Stochmal A. Isolation, chemical characterization, and free radical scavenging activity of phenolics from Triticum aestivum L. aerial parts. J Agric Food Chem. 2014;62(46):11200–11208. doi: 10.1021/jf5038689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larue C, Castillo-Michel H, Sobanska S, Cécillona L, Bureaua S, Barthèsd V, Ouerdane L, Carrièref M, Sarret G. Foliar exposure of the crop Lactuca sativa to silver nanoparticles: evidence for internalization and changes in Ag speciation Camille. J Hazard Mater. 2014;264:98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2013.10.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latif HH, Ghareib M, Abu Tahon M. Phytosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using leaf extracts from Ocimum basilicum and Mangifira indica and their effect on some biochemical attributes of Triticum aestivum. Gesunde Pflanzen. 2017;69:39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Laware SL, Raskar S. Effect of titanium dioxide nanoparticles on hydrolytic and antioxidant enzymes during seed germination in onion. Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci. 2014;3(7):749–760. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi H, Esmailpour M, Gheranpaye A. Effects of TiO2 nanoparticles and water-deficit stress on morpho-physiological characteristics of dragonhead (Dracocephalum moldavica L.) plants. Acta Agric Slov. 2016;107(2):385–396. [Google Scholar]

- Mosa KA, El-Naggar M, Ramamoorthy K, Alawadhi H, Elnaggar A, Wartanian S, Ibrahim E, Hani H. Copper nanoparticles induced genotoxicty, oxidative stress, and changes in superoxide dismutase (SOD) gene expression in cucumber (Cucumis sativus) plants. Front Plant Sci. 2018;9:872. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukwevho E, Ferreira Z, Ayeleso A. Potential role of sulfur-containing antioxidant systems in highly oxidative environments. Molecules. 2014;19:19367–19389. doi: 10.3390/molecules191219376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair PMG, Chung IM. Assessment of silver nanoparticle-induced physiological and molecular changes in Arabidopsis thaliana. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2014;21:8858–8869. doi: 10.1007/s11356-014-2822-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano Y, Asada K. Hydrogen peroxide is scavenged by ascorbate-specific peroxidase in spinach chloroplasts. Plant Cell Physiol. 1981;22:867–880. [Google Scholar]

- Novack B, Bucheli TD. Occurrence, behavior and effect of nanoparticles in the environment. Environ Pollut. 2007;150:5–22. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ober JA (2003) Materials flow of sulfur. US Geological Survey Open File Report 02-298

- Penner D, Aston FM. Hormonal control of proteinase activity in squash cotyledons. Plant Physiol. 1969;42:791–796. doi: 10.1104/pp.42.6.791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peralta-Videa JR, Hernandez-Viezcas JA, Zhao L, Diaz BC, Ge Y, Priester JH, Holden PA, Gardea-Torresdey JL. Cerium dioxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles alter the nutritional value of soil cultivated soybean plants. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2014;80:128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2014.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad R, Pandey R, Barman I. Engineering tailored nanoparticles with microbes: quovadis? Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol. 2016;8(2):316–330. doi: 10.1002/wnan.1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond J, Rekariyathem N, Azanza JL. Purification and some properties of polyphenol oxidase from sunflower seed. Phytochemistry. 1993;34:927–931. [Google Scholar]

- Riffat A, Aqeel Ahmad MS. Changes in organic and inorganic osmolytes of maize (Zea mays L.) by sulfur application under salt stress conditions. J Agric Sci. 2018;10(12):543–561. [Google Scholar]

- Roco MC. Nanotechnology convergence with modern biology and medicine. Curr Opin Biotech. 2003;14:337–346. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(03)00068-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rui M, Ma C, Tang X, Yang J, Jiang F, Pan Y, Xiang Z, Hao Y, Rui Y, Cao W, Xing B. Phytotoxicity of silver nanoparticles to peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.): physiological responses and food safety. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2017;5(8):6557–6567. [Google Scholar]

- Salem NM, Albanna LS, Awwad AM, Ibrahim QM, Abdeen AO. Green synthesis of nano-sized sulfur and its effect on plant growth. J Agric Sci. 2016;8(1):188–194. [Google Scholar]

- Salem NM, Albanna LS, Awwad AM. Green synthesis of sulfur nanoparticles using Punica granatum peels and the effects on the growth of tomato by foliar spray applications. Environ Nanotechnol Monit Manag. 2016;6:83–87. [Google Scholar]

- Shamsa F, Monsef H, Ghamooshi R, Verdian-rizi M. Spectrophotometric determination of total alkaloids in some Iranian medicinal plants. Thai J Pharm Sci. 2008;32:17–20. [Google Scholar]

- Shankar S, Pangen R, Park JW, Rhim JW. Preparation of sulfur nanoparticles and their antibacterial activity and cytotoxic effect. Mater Sci Eng, C. 2018;92:508–517. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2018.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma P, Bhatt D, Zaidi MGH, Pardha Saradhi P, Khanna PK, Arora S. Silver nanoparticle-mediated enhancement in growth and antioxidant status of Brassica juncea. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2012;167:2225–2233. doi: 10.1007/s12010-012-9759-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims DA, Gamon JA. Relationships between leaf pigment content and spectral reflectance across a wide range of species, leaf structures and developmental stages. Remote Sens Environ. 2002;81:337–354. [Google Scholar]

- Suleiman M, Al-Masri M, Al Ali A, Aref D, Hussein A, Iyad Saadeddin I, Warad I. Synthesis of nano-sized sulfur nanoparticles and their antibacterial activities. J Mater Environ Sci. 2015;6:513–518. [Google Scholar]

- Teles YCF, Horta CCR, Agra MF, Siheri W, Boyd M, Igoli JO, Gray AI, de Souza MFV. New Sulphated Flavonoids from Wissadula periplocifolia (L.) C. Presl (Malvaceae) Molecules. 2015;20:20161–20172. doi: 10.3390/molecules201119685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathia RM, Rao PR, Tsuzuki T. Green synthesis of sulfur nanoparticles and evaluation of their catalytic detoxification of hexavalent chromium in water. RSC Adv. 2018;8:36345–36352. doi: 10.1039/c8ra07845a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velikova V, Yordanov I, Edreva A. Oxidative stress and some antioxidant systems in acid rain-treated bean plants. Plant Sci. 2000;15:59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang HY, Jiang YN, He ZY, Ma M. Cadmium accumulation and oxidative burst in garlic (Allium sativum) J Plant Physiol. 2005;162:977–984. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P, Ma Y, Liu S, Wang G, Zhang J, He X, Zhang J, Rui Y, Zhang Z. Phytotoxicity, uptake and transformation of nano-CeO2 in sand cultured. Environ Pollut. 2017;220:1400–1408. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.10.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhishen J, Mengcheng T, Jianming W. The determination of flavonoid contents in mulberry and their scavenging effects on superoxide radicals. Food Chem. 1999;64(4):555–559. [Google Scholar]