Abstract

Bacterial type VII secretion systems secrete a wide range of extracellular proteins that play important roles in bacterial viability and in interactions of pathogenic mycobacteria with their hosts. Mycobacterial type VII secretion systems consist of five subtypes, ESX-1–5, and have four substrate classes, namely, Esx, PE, PPE, and Esp proteins. At least some of these substrates are secreted as heterodimers. Each ESX system mediates the secretion of a specific set of Esx, PE, and PPE proteins, raising the question of how these substrates are recognized in a system-specific fashion. For the PE/PPE heterodimers, it has been shown that they interact with their cognate EspG chaperone and that this chaperone determines the designated secretion pathway. However, both structural and pulldown analyses have suggested that EspG cannot interact with the Esx proteins. Therefore, the determining factor for system specificity of the Esx proteins remains unknown. Here, we investigated the secretion specificity of the ESX-1 substrate pair EsxB_1/EsxA_1 in Mycobacterium marinum. Although this substrate pair was hardly secreted when homologously expressed, it was secreted when co-expressed together with the PE35/PPE68_1 pair, indicating that this pair could stimulate secretion of the EsxB_1/EsxA_1 pair. Surprisingly, co-expression of EsxB_1/EsxA_1 with a modified PE35/PPE68_1 version that carried the EspG5 chaperone-binding domain, previously shown to redirect this substrate pair to the ESX-5 system, also resulted in redirection and co-secretion of the Esx pair via ESX-5. Our results suggest a secretion model in which PE35/PPE68_1 determines the system-specific secretion of EsxB_1/EsxA_1.

Keywords: mycobacteria, protein secretion, substrate specificity, tuberculosis, Western blot, gene knockout, ESX-1, EsxA, PPE68, type VII secretion

Introduction

Mycobacteria possess an unusual hydrophobic cell envelope that protects them from various stresses and contributes to the resilience of pathogenic mycobacteria during infection. Classified as guanine-cytosine rich Gram-positive bacteria, the cell envelope of mycobacteria consists of a relatively standard cell membrane with a surrounding peptidoglycan layer. However, mycobacteria belong to a subgroup of guanine-cytosine rich Gram-positive bacteria that have acquired an extra hydrophobic layer of long-chain fatty acids, called mycolic acids. These specific lipids are covalently linked via an arabinogalactan layer to the peptidoglycan layer, forming a highly rigid and impermeable structure. Mycobacteria employ specialized machineries, called type VII secretion systems (T7SSs)3 to secrete proteins across their complex cell envelope (1, 2). Mycobacterium tuberculosis possesses five of such T7SSs, named ESX-1 to ESX-5 (1, 2), of which ESX-1, ESX-3, and ESX-5 have been functionally analyzed (3–10). Each of these systems plays a different role in the mycobacterial life cycle. For example, ESX-1 has a key role in virulence of pathogenic mycobacteria, because it mediates phagosomal rupture inside macrophages (11–14) and the subsequent escape of M. tuberculosis from the phagolysosome (3–6, 15, 16). ESX-3 and ESX-5 are necessary for iron and fatty acid uptake, respectively, making these systems essential for bacterial viability (7–10). In addition to their roles in nutrient and metabolite acquisition, ESX-3 and ESX-5 are involved in immune modulation of the host (9, 17, 18).

The substrates that are secreted by these three ESX systems belong to distinctive protein families, i.e. Esx, PE, PPE, and Esp proteins, most of them belonging to the so-called EsxAB clan (Pfam CL0352) (19). Within this clan, the Esx proteins belong to the WxG100 family of proteins that contain an WxG protein motif and are generally 100 amino acids long. The PE and PPE proteins are named after proline–glutamic acid (PE) and proline–proline–glutamic acid (PPE) motifs in their N-terminal domains, respectively (20). These N-terminal homology domains consist of roughly 110 amino acids for the PE protein family and 180 amino acids for the PPE protein family (20). The C-terminal domains of PE and PPE proteins vary extensively in length and sequence (20).

ESX substrates have been shown to form heterodimers in the cytosol, i.e. two Esx proteins pair together and PE proteins pair with a PPE protein, and are thought to be secreted as (partially) folded heterodimers (13, 21–24). Crystal structures have been solved for several heterodimeric substrates of different ESX systems, revealing highly conserved features in which the interface of Esx heterodimers (26, 27), as well as the interface of PE/PPE heterodimers, is formed by two helix–turn–helix structures oriented antiparallel to each other (22, 23, 28). Interestingly, each ESX system secretes its own subset of Esx, PE, and PPE substrates that are most likely responsible for the various roles of ESX systems in the bacterial life cycle. How these structurally similar proteins are specifically targeted to their corresponding ESX system still remains unclear. A conserved T7SS secretion signal (YXXX(D/E)) has been identified that is located directly after the helix–turn–helix domain of one partner protein of the Esx heterodimer and the PE partner of the PE/PPE heterodimer. This signal, although required for secretion, is exchangeable among PE substrates of different ESX systems without changing their initial secretion route (29, 30). Hence, this signal does not determine system-specific secretion of these ESX substrates.

Structural analysis showed that the conserved N termini of PPE proteins contain, in addition to the helix–turn–helix structure, an extra domain that is not present in Esx and PE proteins. This relatively hydrophobic helical tip domain extends from the characteristic four-helix bundle formed by the PE-PPE interface (22, 23). This domain is recognized by a cytosolic chaperone, called EspG, in a system-specific manner (Fig. S1), an interaction that is required for secretion of the PE/PPE pair (22, 23, 31). Previously, we could establish the redirection of the ESX-1 substrate pair PE35/PPE68_1 to the ESX-5 system by replacing its EspG1 chaperone-binding domain with the equivalent domain of the ESX-5 substrate PPE18 (32). This suggests that this domain determines through which system these substrates are transported. The remaining question is how the Esx substrate pairs that lack this extended tip domain are specifically recognized and targeted to their designated systems.

Here, we investigated the signals that determine the system specificity of Esx substrates in Mycobacterium marinum using the ESX-1 heterodimer EsxB_1/EsxA_1 as model substrates. Its encoding genes esxB_1/esxA_1 (MMAR_0187/MMAR_0188) are adjacent to pe35/ppe68_1 (MMAR_0185/MMAR_0186), which are gene products we have previously used as a model ESX-1–dependent PE/PPE heterodimer (31, 32). We found that EsxB_1/EsxA_1 secretion via the ESX-1 system was severely enhanced by the co-expression and secretion of PE35/PPE68_1. Although previous genetic studies have already reported co-dependence of ESX-1 substrates for secretion (33–37), this observation also indicates that balanced expression levels of both heterodimers are required for optimal secretion via ESX-1. Interestingly, the EsxB_1/EsxA_1 pair could be rerouted to the ESX-5 system by solely exchanging the EspG-binding domain in PPE68_1. This not only confirms the strict dependence of the EsxB_1/EsxA_1 heterodimer on PE35/PPE68_1 for secretion but also reveals that this PE/PPE pair determines the system specificity of this Esx pair.

Results

EsxB_1/EsxA_1 require co-expression of PE35/PPE68_1 for efficient ESX-1–dependent secretion

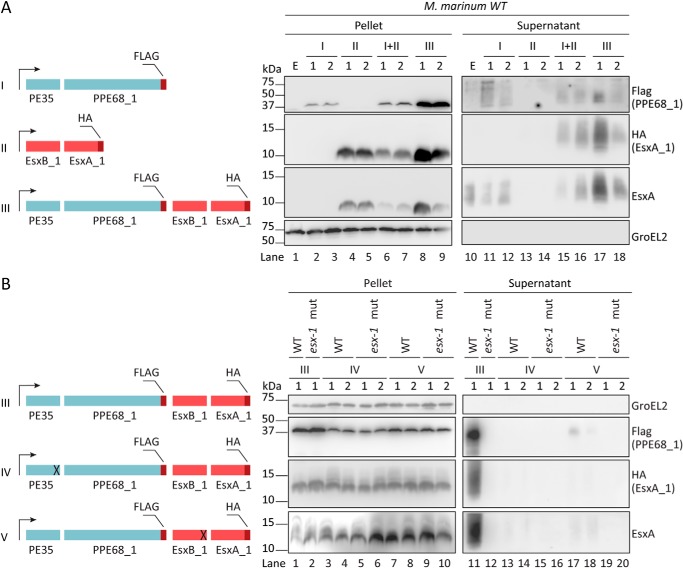

To investigate how the system-specific secretion of Esx substrates is achieved, we investigated the secretion requirements of EsxB_1/EsxA_1 in M. marinum. The corresponding coding genes (MMAR_0187/MMAR_0188) lie adjacent to the gene pair pe35/ppe68_1 (MMAR_0185/MMAR_0186) and are paralogs of the pe35–ppe68–esxB–esxA gene cluster located in the esx-1 locus (Fig. 1A). We introduced a multicopy plasmid containing esxB_1/esxA_1, expressed under the constitutive hsp60 promoter, in WT M. marinum (38). We also included WT M. marinum containing the previously analyzed pe35/ppe68_1 gene pair controlled by the same promoter on an integrative plasmid as an ESX-1 substrate control (32). Secretion was analyzed by immunoblotting using the introduced HA and FLAG epitopes at the C termini of EsxA_1 and PPE68_1, respectively (Fig. 2A). To assess the possible variation in secretion between different colonies, we consistently checked duplicates of the same transformants throughout this study. The cytosolic protein GroEL2 was not detected in the culture supernatant fractions of all analyzed cultures, confirming the integrity of the bacterial cells. Consistent with published data (29, 32), PPE68_1–FLAG was detected in the culture supernatant fraction of the WT strain as a faint smeary band of ∼40 kDa (Fig. 2A, lanes 11 and 12). Whereas EsxA_1–HA was well-expressed, as judged from the HA signals detected in the pellet fractions (Fig. 2A, lanes 4 and 5), this protein was not secreted by the WT strain (Fig. 2A, lanes 13 and 14). Surprisingly, secretion of endogenous EsxA, detected by an EsxA antibody, was severely affected by the overexpression of EsxB_1/EsxA_1 (Fig. 2A, lanes 13 and 14). To investigate the impact of EsxB_1/EsxA_1 overexpression also on other ESX-1 substrates, secretion of EspE was investigated (Fig. S2). This substrate remains attached to the bacterial surface in M. marinum and can be extracted by the mild detergent Genapol X-080. The presence of EspE in the Genapol-extracted fraction was completely abolished in the strain overexpressing EsxB_1/EsxA_1, indicating that this homologously expressed pair has a broad effect on ESX-1 secretion (Fig. S2, lanes 13 and 14). Because several T7SS substrates, in particular those of the ESX-1 system, have been shown to be dependent on each other for secretion (32, 34, 39), we hypothesized that the secretion of overexpressed EsxB_1/EsxA_1 might require the co-expression of the PE35/PPE68_1 pair that is putatively located in the same operon. Similarly organized loci containing a pe/ppe pair and an adjacent esx gene pair can be observed in other ESX clusters. We co-electroporated the integrative pMV361::pe35/ppe68_1-flag and the multicopy pSMT3::esxB_1/esxA_1-ha in WT M. marinum. Secretion analysis followed by immunoblotting showed that the co-expression of EsxB_1/EsxA_1–HA did not seem to affect the expression or secretion of PPE68_1–FLAG (Fig. 2A, lanes 6, 7, 15, and 16). In contrast, EsxA_1–HA was now efficiently secreted and detected as a smeary band of ∼15 kDa in the supernatant of the strain that co-expressed both the PE/PPE and the Esx substrate pairs (Fig. 2A, lanes 15 and 16). Furthermore, the immunoblot signals in the supernatant fractions using the EsxA antibody, which probably detects both EsxA_1–HA and endogenous EsxA, became comparable with that of the WT strain without any constructs (Fig. 2A, lanes 15 and 16). However, the presence of EspE in the Genapol-extracted fraction was not restored in the strain overexpressing both the Esx and PE/PPE pair, suggesting that the secretion of endogenous ESX-1 substrates was still blocked (Fig. S2, lanes 15 and 16). These data show that the efficient secretion of overexpressed EsxA_1–HA relies on the co-overexpression of PE35/PPE68_1–FLAG.

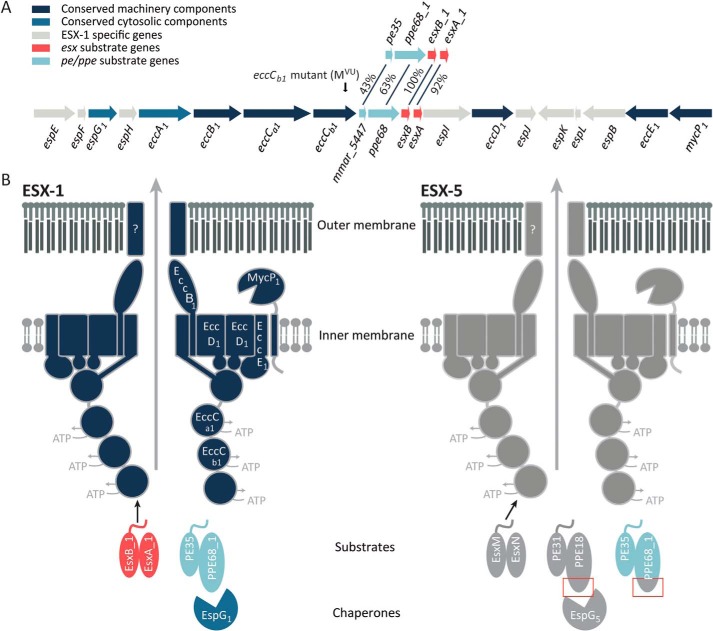

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the esx-1 locus and the ESX-1 and ESX-5 secretion system. A, genetic organization of the esx-1 locus and the duplicated region containing pe35/ppe68_1/esxB_1/esxA_1. Genes are color-coded according to the localization of their encoded proteins (see color key). The frameshift mutation in the eccCb1 mutant (also named MVU) used in this study is indicated by an arrow. B, current model of substrate recognition by the type VII secretion systems. Shown are the model substrates used in this study, i.e. the ESX-1 substrate pairs EsxB_1/EsxA_1 and PE35_1/PPE68_1 and the ESX-5 substrate pairs EsxM/EsxN and PE31/PPE18. Previously, PPE68_1 has been shown to be rerouted to the ESX-5 system by exchanging the EspG1-binding domain with the equivalent domain of PPE18, indicated by red boxes (32). EspG components recognize cognate PE/PPE substrates, independently of the general secretion signal located in the C-terminal tails of the PE proteins. This recognition is required for secretion via the cognate secretion machinery located in the mycobacterial inner membrane. Recognition of Esx substrates by the T7SS membrane complex occurs through the interaction of the C-terminal tail of one of the Esx partner proteins with the third nucleotide-binding domain of EccC (46, 47). How PE/PPE pairs are recognized by this complex remains unclear. Notably, only the conserved N-terminal domains of the PE and PPE proteins are shown in this model.

Figure 2.

Homologously expressed EsxA_1/EsxB_1 require co-expression and secretion of PE35/PPE68_1 for efficient secretion via the ESX-1 system. A, a schematic representation of the different constructs used are shown on the left. The four genes encoding the M. marinum ESX-1 substrates PE35/PPE68_1 (in blue) and EsxB_1/EsxA_1 (in pink) are either expressed from separate hsp60 promoters (I and II) or co-expressed under the same hsp60 promoter (III). Immunoblot analysis was performed of the cell pellet and culture supernatant fractions of WT M. marinum using an HA antibody to detect EsxA_1–HA, a FLAG-antibody to detect PPE68_1–FLAG, an EsxA antibody, detecting both endogenous and exogenous EsxA paralogs, and a GroEL2 antibody to detect the intracellular control protein GroEL2. B, a schematic representation of the different constructs used is shown on the left; deletions are indicated by ×. Immunoblot analysis using the same antibodies as under A to analyze secretion by WT and the ESX-1 mutant. In all blots, equivalent OD units were loaded; 0.2 OD for pellet and 0.5 OD for supernatant fractions. Numbers indicate two independent M. marinum colonies carrying the same construct. E, empty strain.

Because the integrative pMV361 plasmid and the multicopy pSMT3 plasmid differ in copy numbers, thereby possibly resulting in suboptimal co-secretion of the two substrate pairs, we also introduced the complete pe35/ppe68_1/esxB_1/esxA_1 locus into the pSMT3 plasmid again with a FLAG and HA tag fused to the C termini of PPE68_1 and EsxA_1, respectively. The construct is hereafter referred to as the ALL WT construct. We observed that although the cellular levels of both EsxA_1–HA and PPE68_1–FLAG were increased (Fig. 2A, lanes 8 and 9), the secretion of EsxA_1–HA was similar to the condition when the two substrate pairs were independently expressed (Fig. 2A, lanes 17 and 18). Taken together, our data suggest that the co-expression of PE35/PPE68_1, but not its co-transcription, increases the secretion of homologously expressed EsxB_1/EsxA_1 in M. marinum.

We next investigated whether the secretion of overexpressed EsxA_1 requires not only co-overexpression but also co-secretion of PPE68_1. To test this, the C-terminal 15 and 21 amino acids of PE35 and EsxB_1, respectively, containing the YXXX(D/E) secretion motif, were deleted, which abolishes their secretion. We analyzed the effect of these truncations on the secretion of PPE68_1 and EsxA_1 in the WT and an eccCb1 mutant strain (esx-1 mutant), previously described as a nonfunctional esx-1 mutant (40) (Fig. 2B). In all tested cultures, the supernatants were devoid of GroEL2, indicating the integrity of the cells (Fig. 2B). Secretion of both EsxA-HA and PPE68_1–FLAG was abolished in the esx-1 mutant strain, confirming that these proteins are secreted via the ESX-1 secretion system (Fig. 2B, lane 12). Importantly, immunoblot analysis showed that the deletion of the C-terminal tail of either PE35 or EsxB_1 disrupted the secretion of both PPE68_1 and EsxA_1 in WT M. marinum (Fig. 2B, lanes 13, 14, 17, and 18). Only some minor secretion of PPE68_1 was observed in the WT strain, but not in the esx-1 mutant strain, when the secretion signal in EsxB_1 was deleted (Fig. 2B, lanes 17 and 18). We therefore conclude that the presence of both the PE35 and EsxB_1 C-terminal tails, containing the T7SS secretion signal, are required for the secretion of both substrates. This indicates that EsxB_1/EsxA_1 and PE35/PPE68_1 are co-dependently secreted via the ESX-1 system.

WT EsxB_1/EsxA_1 is rerouted to the ESX-5 system by introducing the EspG5-binding domain in PPE68_1

Two different domains in ESX substrates have been identified that are important for secretion: the YXXX(D/E) motif, located in the C-terminal tail directly after the helix–turn–helix domain of some Esx and all PE proteins, and the EspG-binding domain in the conserved N-terminal domain of PPE proteins. Although the C-terminal tails of PE substrates, secreted through different ESX systems, can in general be exchanged without changing their predetermined secretion route (29), in a previous study we have been able to redirect PPE68_1 to the ESX-5 system by exchanging its EspG1 chaperone-binding domain with the equivalent domain of the ESX-5 substrate PPE18 (32).

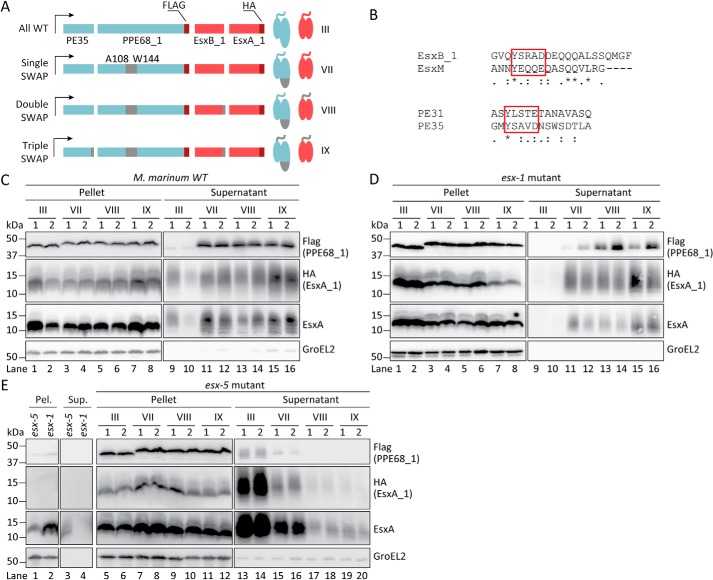

Here, we aimed to determine which signals are required for establishing rerouting of EsxA_1 to the ESX-5 system, starting by investigating the role of the EspG-binding domain of the co-expressed PE/PPE pair. For this, we constructed pe35/ppe68_1/esxB_1/esxA_1, in which ppe68_1 was engineered to express a PPE68_1 variant that carries the EspG5-binding domain of the PPE18 protein (Figs. 1B and 3A), as previously described (32). This entire construct was named SINGLE SWAP (Fig. 3A), and the modified PPE68_1 protein was named PPE68_1 SWAP. This construct was introduced in M. marinum WT, esx-1, and esx-5 mutant strains, after which secretion was analyzed and compared with the same strains expressing the already explained ALL WT construct.

Figure 3.

EsxA_1 is co-rerouted to ESX-5 by introducing the EspG5-binding domain of ESX-5 substrate PPE18 into PPE68_1. A, schematic representation of the different constructs used in the secretion analysis. The introduced sequences of the ESX-5 substrates PE31/PPE18 are in gray. The FLAG tag (on PPE68_1) and HA tag (on EsxA_1) are shown in red. B, alignment of the swapped sequences containing the C-terminal secretion motifs of the ESX-5 substrates PE31 and EsxM and the ESX-1 substrates PE35 and EsxB_1, respectively. The conserved secretion motif YXXX(D/E) are highlighted with red boxes. C–E, immunoblot analysis of EsxA_1 as detected with an HA antibody, PPE68_1 as probed with a FLAG antibody and endogenous and exogenous EsxA paralogs using an EsxA antibody and intracellular GroEL2 by an GroEL2 antibody, in pellet and supernatant fractions. Different derivatives of PE35/PPE68_1/EsxB_1/EsxA_1 were tested in WT M. marinum (C), an eccCb1 mutant (esx-1 mutant; D), and an eccC5 knockout strain (esx-5 mutant; E). Equivalent OD units of cell pellets (0.2 OD unit) and culture supernatants (0.5 OD unit) are shown. Numbers indicate two independent M. marinum colonies carrying the same construct.

Interestingly, we observed that the presence of the SINGLE SWAP construct seemed to induce minor lysis of WT M. marinum cells, because a small amount of GroEL2 was consistently detected in the supernatants of these cultures (Fig. 3C). Nevertheless, the detected amount of GroEL2 was comparable among the strains expressing the different constructs, allowing further analysis. As observed before, the expression of the ALL WT construct resulted in expression and secretion of both PPE68_1–FLAG and EsxA_1–HA (Fig. 3C, lanes 1, 2, 9, and 10). The EsxA antibody was included to confirm the total EsxA expression and secretion (Fig. 3C, lanes 1, 2, 9, and 10). As seen previously for PPE68_1 SWAP (32), we observed that the PPE68_1 hybrid expressed from the SINGLE SWAP construct appeared as a slightly higher band than the PPE68_1 WT and was efficiently secreted in the WT strain (Fig. 3C, lanes 3, 4, 11, and 12). Notably, although secretion of PPE68_1 SWAP was more efficient than PPE68_1 WT (32), the amount of EsxA_1 was also higher in the supernatant fractions, as judged by an increased intensity of both HA and EsxA signals (Fig. 3C, lanes 11 and 12).

We subsequently addressed the involved secretion systems by first introducing the SINGLE SWAP construct in the esx-1 mutant strain. In contrast to WT M. marinum cells, GroEL2 was not detected in the supernatant fractions of this mutant strain, indicating the integrity of the cells in the presence of the constructs (Fig. 3D). As expected, secretion of both PPE68_1–FLAG and EsxA_1–HA of the ALL WT construct was abrogated (Fig. 3D, lanes 9 and 10). In contrast, the PPE68_1 SWAP protein was still secreted (Fig. 3D, lanes 11 and 12), confirming our previous observation that the PPE68_1 SWAP was secreted independently of the ESX-1 system (32). Importantly, we also still detected EsxA_1 in the supernatant, using both the HA and the EsxA antibody (Fig. 3D, lanes 11 and 12), suggesting that this ESX-1 substrate is now secreted in an ESX-1–independent manner as well. This is highly interesting because both EsxA_1 and EsxB_1 are unmodified in the SINGLE SWAP construct. Together, these data suggest that PPE68_1 SWAP determines the ESX-1–independent secretion of EsxA_1.

To confirm that PPE68_1 SWAP and EsxA_1 are secreted by the ESX-5 system, we introduced the SINGLE SWAP construct in the ΔeccC5 strain. EccC5 is an essential component of the ESX-5 machinery (41, 42), and deletion of this component blocks ESX-5–dependent secretion (7). In this strain, the presence of the tested SINGLE SWAP construct consistently caused minor bacterial lysis, indicated by the presence of GroEL2 in the supernatant fractions (Fig. 3E). Because a similar phenotype was observed for the same construct in the WT strain, but not in the esx-1 mutant, the bacterial leakage induced upon homologous expression of these proteins seemed to be linked to a functional ESX-1 system. Expressing the ALL WT construct, both PPE68_1–FLAG and EsxA_1–HA were detected in the supernatant fractions of the ΔeccC5 strain by using the FLAG and HA antibody, respectively (Fig. 3E, lanes 13 and 14). Notably, more intense EsxA signals could be observed in the supernatant fraction of the esx-5 mutant containing the ALL WT construct (Fig. 3E, lanes 13 and 14), compared with the empty ΔeccC5 strain (Fig. 3E, lane 3). This indicates that overexpressed EsxA_1 is particularly well-secreted in this strain. The PPE68_1 SWAP and EsxA_1 of the SINGLE SWAP were only moderately detected in the supernatant of the ΔeccC5 strain (Fig. 3E, lanes 15 and 16). Thus, our data show that the secretion of both proteins became mostly dependent on the ESX-5 system when the EspG5-binding domain was present. The observed residual secretion of PPE68_1–FLAG and EsxA_1–HA with the SINGLE SWAP construct indicates that a small amount of these substrate pairs can still be secreted via ESX-1. Interestingly, we previously have shown that secretion of PPE68_1 SWAP was completely blocked in the same esx-5 mutant in the absence of overexpressed EsxB_1/EsxA_1 (32). This indicates that this Esx substrate pair might be able to guide some amount of PPE68_1 SWAP to the ESX-1 system.

Finally, we observed a competitive correlation between the secretion of the rerouted substrates PE35/PPE68_1 SWAP and native substrates of the ESX-5 system, i.e. the PE_PGRS proteins. Using the Genapol extraction method to analyze the surface localization of PE_PGRS proteins, we observed a lower amount of these proteins in the Genapol-extracted fraction in the esx-1 mutant strain expressing the SINGLE SWAP construct, compared with the esx-1 mutant strain expressing the ALL WT construct (Fig. S3). This suggests that, similar to what was reported previously, the redirection of ESX-1 substrates to the ESX-5 system interferes with the export of endogenous ESX-5 substrates (32). Interestingly, however, WT M. marinum expressing the SINGLE SWAP construct was still unable to secrete EspE, another ESX-1–dependent substrate (Fig. S2, lanes 19 and 20). This suggests that redirection of PPE68_1 SWAP and EsxA_1 via ESX-5 does not relieve the ESX-1 secretion block that was observed when overexpressing the WT PE35/PPE68_1–FLAG and EsxB_1/EsxA_1–HA heterodimers in M. marinum WT.

In summary, introducing the EspG5-binding domain in PPE68_1 resulted in the rerouting of both the PPE68_1 and EsxA_1 substrate to the ESX-5 system. This observation not only further confirms that these proteins are co-secreted but also shows that the PPE protein is involved in determining the system specificity of the Esx substrate.

The redirection of EsxB_1/EsxA_1 via the ESX-5 system can be further improved by exchanging the T7SS secretion signals

Although the C-terminal tails, containing the YXXX(D/E) secretion motif, of PE proteins are essentially not involved in determining the system specificity of PE/PPE pairs (29), we investigated next the role of the equivalent domain of Esx proteins in substrate redirection. For this, we constructed an additional pe35/ppe68_1/esxB_1/esxA_1 construct, in which the C-terminal domain EsxB_1, containing the YXXX(D/E) motif, was replaced by the equivalent region of the ESX-5 substrate EsxM (Fig. 3B). We observed, however, that exchanging this domain abolished secretion of EsxA_1–HA in WT M. marinum (Fig. S4, lanes 16 and 17). This is in agreement with a previous study showing that exchanging the C-terminal domain in PE35 with the equivalent domain of PE31 blocks secretion of PPE68_1 in the same WT strain (32).

We therefore investigated next whether exchanging the T7SS secretion signals in EsxB_1 and PE35 could improve the redirection of our SINGLE SWAP construct, i.e. in which the EspG-binding domain of PPE68_1 was exchanged (Fig. 3A). The construct, in which the C-terminal amino acids of EsxB_1 was exchanged with the equivalent residues of EsxM (Fig. 3B), was designated DOUBLE SWAP. In addition, we replaced the 15-amino acid C-terminal domain of the PE35 by the corresponding region of the ESX-5 substrate PE31 (Fig. 3B), resulting in the construct of TRIPLE SWAP, i.e. this construct carried three exchanged domains (Fig. 3A). The secretion of these variants was again analyzed in M. marinum WT and the esx-1 and esx-5 mutant strain.

The presence of the DOUBLE and TRIPLE SWAP constructs seemed to cause minor lysis of WT M. marinum cells, similar to the SINGLE SWAP construct (Fig. 3C). The presence of the C-terminal tail of EsxM in the DOUBLE SWAP construct did not affect the expression or secretion of PPE68_1 SWAP or EsxA_1, because similar intensities of the detected signals were observed compared with those of the SINGLE SWAP substrates (Fig. 3C, lanes 5, 6, 13, and 14). However, when ESX-5 secretion signals were introduced in both PE35 and EsxB_1, the secretion of both the PPE68_1 SWAP and EsxA_1 seemed to reach the highest efficiency (Fig. 3C, lanes 15 and 16).

In the esx-1 mutant strain, GroEL2 was not detected in the supernatant fractions, indicating the integrity of the cells in the presence of these two constructs (Fig. 3D). Here, the DOUBLE SWAP construct induced comparable levels of EsxA_1 secretion as the SINGLE SWAP construct (Fig. 3D, lanes 13 and 14), whereas the secretion of EsxA_1 appeared most efficient in the presence of both the ESX-5 secretion signals in the TRIPLE SWAP construct (Fig. 3D, lanes 15 and 16). The competitive correlation between the secretion of the rerouted substrates and the ESX-5–dependent PE_PGRS proteins was also observed in the esx-1 mutant expressing the DOUBLE SWAP and the TRIPLE SWAP construct (Fig. S3, lanes 13–16). Finally, no PPE68_1 SWAP and only a minor amount of EsxA_1 was detected in the supernatants of ΔeccC5 strains, containing either the DOUBLE or the TRIPLE SWAP construct (Fig. 3E, lanes 17–20). From these data, we conclude that the exchange of the EspG-binding domain in PPE68_1 is essential and sufficient for redirection of both the PE/PPE and Esx pair, whereas the general secretion motifs merely improve redirection efficiency to the ESX-5 system.

Discussion

Each mycobacterial T7SS secretes their own subset of Esx, PE, and PPE proteins, which share sequence similarities and show structural resemblance. This phenomenon raises the question of how these substrates are specifically recognized by the T7SS subtypes. Recently, we showed that the system specificity of the PE/PPE substrates is determined by the EspG chaperone-binding domain on the PPE protein (32). However, a similar mechanism for system-specific recognition cannot apply to the Esx heterodimers, because they lack this chaperone-binding domain and therefore cannot interact with the EspG chaperones (31). In this study, we show that the PE35/PPE68_1 heterodimer defines the system-specific secretion of EsxB_1/EsxA_1 in M. marinum.

We found that ESX-1–dependent secretion of overexpressed EsxB_1/EsxA_1 is severely enhanced when PE35/PPE68_1 were co-overexpressed. Co-expression of PE35/PPE68_1 from the same promoter was not required for EsxA_1 secretion, suggesting that this dependence is not transcriptionally linked. Our previous observation that deletion of espG1 leads to a loss of not only PE/PPE secretion but also of EsxB/EsxA and other ESX-1 substrates in M. marinum (32, 44) already hinted toward the dependence of EsxB/EsxA on PE/PPE substrates for their secretion. Interestingly, in M. tuberculosis the dependence of EsxA secretion on PPE68 seems more complex. Although PPE68 itself is indeed crucial for EsxA secretion, an espG1 deletion in this species, which is predicted to affect PPE68, does not seem to affect EsxA secretion (4, 39). Because there is only a single copy of esxA in the genome of M. tuberculosis, contrary to the four highly homologous esxA copies M. marinum, it is possible that the two pathogens employ distinct mechanisms to govern the regulation and/or secretion of EsxA. Alternatively, there might be redundancy of different PE/PPE proteins in M. tuberculosis in facilitating the secretion of EsxA, or EspG1 is less important for ESX-1 secretion in M. tuberculosis.

In this study, we also confirmed that the C-terminal tails of PE35 and EsxB_1, containing the YXXX(D/E) secretion motifs, are required for the secretion of the corresponding heterodimer, consistent with other studies (29). Moreover, the finding that both secretion motifs are strictly required for the secretion of both heterodimers is highly interesting. These data show that the secretion of EsxA_1 is dependent not only on the co-overexpression but also on the co-secretion of PE35/PPE68_1. In addition, the observation that secretion of PPE68_1 was diminished when the secretion of EsxB_1/EsxA_1 was blocked, by deleting the secretion signal of EsxB_1, suggests that both heterodimers are mutually dependent on each other for their export. Interestingly, the cytosolic accumulation of EsxB_1/EsxA_1, which occurs without co-overexpression of PE35/PPE68_1 or when the C-terminal tails of PE35 and/or EsxB_1 was deleted, also abolishes the secretion of endogenous EsxA and EspE. This is in agreement with our previous observation that the introduction of an ESX-5 secretion signal in PE35 of homologously expressed PE35/PPE68_1 results in a secretion block of both PPE68_1 and endogenous EsxA (32). Possibly, a cytosolic factor that is required for substrate recognition, e.g. EspG1, is titrated away by these nonsecreted substrates.

The finding that WT EsxB_1/EsxA_1 could be rerouted to the ESX-5 system in M. marinum solely by manipulating the EspG-binding domain of PE35/PPE68_1 is unexpected. The fact that WT EsxB_1/EsxA_1 could be co-rerouted in this manner underlines the strict dependence of EsxB_1/EsxA_1 secretion on PE35/PPE68_1. In addition, secretion of both overexpressed PPE68_1 WT via ESX-1 and PPE68_1 SWAP via ESX-5 does not seem to be enhanced upon co-expression of EsxB_1/EsxA_1. This hints toward a hierarchy in secretion, in which the PE/PPE pair controls and might regulate secretion of EsxB_1/EsxA_1. Co-rerouting of endogenous EsxA by the overexpression of PE35/PPE68_1 SWAP was previously not observed (32), suggesting that expression levels of endogenous Esx and PE/PPE pairs are well-balanced. Interestingly, the ability of the ESX-5 system to secrete the two substrate pairs, although they still carry both ESX-1 secretion signals, reflects its flexibility in secreting a wide range of substrates, as already discussed in other studies (22, 23, 40). Nevertheless, rerouting was most efficient when both PE35 and the EsxB_1 carried the ESX-5 C-terminal secretion signals of PE31 and EsxM, respectively. This suggests that the secretion signals of PE31 and EsxM are more optimal for the recognition and secretion by the ESX-5 machinery.

So far, the reason behind co-dependence among ESX substrates remains unclear. It has been proposed that binding to or activation of the T7SS membrane complex could explain this phenomenon. Previous studies have shown that EsxB binds to the third nucleotide-binding domain (NBD) of the conserved membrane complex component EccCab1 and induces hexamerization of this ATPase in vitro (30, 45–47). Specifically, the last seven amino acids of EsxB have been shown to be essential for this interaction (30). The C terminus of other Esx homologs in M. tuberculosis are likely to be structured similarly to the C terminus of EsxB but do contain different amino acids sequences, suggesting that this domain might be involved in system-specific recognition (30, 46, 48). Importantly, structural analysis of EccC of Thermomonospora curvata have shown that the crucial first NBD is kept in an inactivate state by a specific region in the linker 2 domain that connects the first and second NBD, and binding of EsxB is not able to activate this ATPase activity in vitro (40). It has therefore been suggested that an additional trigger is necessary to activate EccC, which could be the binding of PE/PPE substrates. Interestingly, this hypothesis is supported by a recent study showing a species-specific role for the linker 2 domain of EccC5 in secretion of PE_PGRS proteins, a large subgroup of PE proteins that are secreted via ESX-5 (49). From our study, it seems evident that the secretion of the Esx substrates are closely linked to that of PE/PPE heterodimers. Possibly, they bind simultaneously or sequentially to activate all three ATPase domains of EccC, after which transport through the membrane complex is achieved. Such a model would explain both the necessity for equal expression levels of both heterodimers, as well as the secretion dependence of the Esx pair on the PE/PPE pair that we observed here. However, PE/PPE proteins can only be found in the genus of Mycobacterium, whereas the homologs of the Esx substrates and the EccC core component can be found in a more diverse repertoire of Gram-positive species (1, 20, 50). It will be interesting to see the differences in substrate recognition and secretion between these different systems.

This study indicates that the recognition of both PE/PPE and Esx substrates by the various ESX systems depends on the EspG chaperones. In M. marinum, the role of these chaperones in ESX secretion is essential (32, 44), and the EspG binding is required to keep PE/PPE proteins from aggregating (22). Chaperones with dual roles in preventing aggregation and secretion have also been identified in type III secretion systems (51). Conserved type III secretion system chaperones prevent premature assembly of the injection needle and pore-forming subunits, whereas the effector proteins are targeted to the secretion machinery by binding of their dedicated chaperone partner. Possibly, the EspG chaperones in T7SS have acquired similar roles in keeping substrates in a secretion competent state.

The homolog of EsxA_1, EsxA, is the most-studied ESX substrate and has been suggested to be responsible for ESX-1-induced phagosomal rupture. EsxA has been found to be associated with membrane lysis when a transposon mutant of esxA/esxB was unable to lyse cultured lung epithelial cell lines (4, 52). Further genetic studies in M. marinum have shown that several different transposon mutants defective in EsxA secretion lose hemolytic activity and are attenuated in zebrafish (3, 12, 15, 53), supporting the hypothesis that EsxA is a crucial virulent factor of pathogenic mycobacteria. However, secretion of different ESX-1 substrate classes has been shown to be interdependent on each other (33, 34), e.g. loss of EspA or PPE68 secretion leads to secretion defects of EsxA and vice versa (32, 34). Therefore, studying functions of individual ESX-1 substrates during the mycobacterial infection cycle has been a challenge. Although the protein sequences of EsxB and EsxB_1 are identical, EsxA_1 shares 92% protein sequence identity with EsxA. Given the high similarity, it has been suggested that EsxB_1/EsxA_1 have an equivalent functionality as the esx-1 encoded EsxB/EsxA (25). The observation that WT EsxA_1 can be destined for the ESX-5 system provides a unique platform to investigate exact roles of this protein in host–pathogen interactions. Current research is focusing on the redirection of EsxB/EsxA to directly assess the membrane lysis activity of this substrate pair.

Experimental procedures

Bacterial strains and growth cultures

All mycobacterial strains were grown on Middlebrook 7H10 plates (Difco) containing OADC supplement (oleic acid, albumin, dextrose, and catalase; BD Biosciences) or liquid 7H9 medium containing ADC supplement (BD Biosciences) and the appropriate antibiotics (see below). M. marinum strains were grown at 30 °C, 90 rpm. All mycobacterial strains and mutants are listed in Table S1. Escherichia coli strain DH5α was used for cloning procedures and plasmid accumulation and was grown on lysogeny broth plates or liquid broth at 37 °C, 200 rpm. Growth medium was supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics at the following concentrations: kanamycin (Roche), 25 μg/ml; and hygromycin (Sigma), 50 μg/ml.

Plasmid construction

All PCRs were carried out with the Phusion high-fidelity DNA polymerase (Finnzymes) using primers listed in Table S2. The restriction sites used for cloning are indicated in this table. All plasmids used in this study are listed in Table S3.

Protein secretion and immunoblot analysis

M. marinum strains were grown in 7H9 liquid medium supplemented with ADC, 0.05% Tween 80, and appropriate antibiotics until mid-logarithmic phase, after which the cells were washed and inoculated in 7H9 medium with 0.2% dextrose, 0.05% Tween 80 at an A600 of 0.4 and grown for another 16 h. The cells (pellet) were spun down for 10 min at 6,000 × g, washed with PBS, and resuspended in SDS loading buffer (containing 100 mm DTT and 2% SDS). Supernatants were passed through 0.2-μm-pore-size filter units, and proteins were precipitated with TCA and resuspended in SDS loading buffer. Alternatively, the cells were resuspended in 0.5% Genapol X-080 and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. The samples were spun down, and the pellets were resuspended in SDS sample loading buffer (Genapol Pellet), whereas 5× SDS sample buffer was added to the supernatant containing Genapol X-080 (Genapol Supernatant) to obtain a final concentration of 1× SDS buffer. Proteins were separated on SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and the membranes were stained with anti-GroEL2 (mAb Cs44; John Belisle, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD), anti-PE_PGRS (7C4.1F7) (40), anti-ESAT-6 (mAb Hyb76-8) (43), anti-HA (HA.11; Covance), anti-EspE (polyclonal rabbit antibody; Eric Brown; Genentech), and anti-FLAG (M2 mAb produced in mouse (Sigma).

Data availability statement

All data are contained within this manuscript.

Author contributions

M. P. M. D., T. H. P., W. B., and E. N. G. H. conceptualization; M. P. M. D., T. H. P., R. U., A. R.-C., and E. N. G. H. data curation; M. P. M. D., T. H. P., R. U., W. B., and E. N. G. H. formal analysis; M. P. M. D., T. H. P., R. U., W. B., and E. N. G. H. validation; M. P. M. D., T. H. P., R. U., A. R.-C., W. B., and E. N. G. H. investigation; M. P. M. D., T. H. P., and E. N. G. H. visualization; M. P. M. D., T. H. P., R. U., A. R.-C., W. B., and E. N. G. H. methodology; M. P. M. D., W. B., and E. N. G. H. writing-review and editing; T. H. P., W. B., and E. N. G. H. supervision; T. H. P. and E. N. G. H. writing-original draft; E. N. G. H. resources; E. N. G. H. funding acquisition; E. N. G. H. project administration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Joen Luirink for valuable discussions.

This work was supported by VIDI Grant 864.12.006 (to T. H. P. and E. N. G. H.) and ALW Open Grant ALWOP.319 (to M. P. M. D.) both from the Netherlands Organization of Scientific Research. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article contains Tables S1–S3 and Figs. S1–S4.

- T7SS

- type VII secretion system

- NBD

- nucleotide-binding domain

- HA

- hemagglutinin.

References

- 1. Houben E. N., Korotkov K. V., and Bitter W. (2014) Take five: type VII secretion systems of Mycobacteria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1843, 1707–1716 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bitter W., Houben E. N., Bottai D., Brodin P., Brown E. J., Cox J. S., Derbyshire K., Fortune S. M., Gao L.-Y., Liu J., Gey van Pittius N. C., Pym A. S., Rubin E. J., Sherman D. R., Cole S. T., et al. (2009) Systematic genetic nomenclature for type VII secretion systems. PLoS Pathog. 5, e1000507 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Houben D., Demangel C., van Ingen J., Perez J., Baldeón L., Abdallah A. M., Caleechurn L., Bottai D., van Zon M., de Punder K., van der Laan T., Kant A., Bossers-de Vries R., Willemsen P., Bitter W., et al. (2012) ESX-1–mediated translocation to the cytosol controls virulence of mycobacteria. Cell. Microbiol. 14, 1287–1298 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2012.01799.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hsu T., Hingley-Wilson S. M., Chen B., Chen M., Dai A. Z., Morin P. M., Marks C. B., Padiyar J., Goulding C., Gingery M., Eisenberg D., Russell R. G., Derrick S. C., Collins F. M., Morris S. L., et al. (2003) The primary mechanism of attenuation of bacillus Calmette-Guerin is a loss of secreted lytic function required for invasion of lung interstitial tissue. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 12420–12425 10.1073/pnas.1635213100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gröschel M. I., Sayes F., Simeone R., Majlessi L., and Brosch R. (2016) ESX secretion systems: mycobacterial evolution to counter host immunity. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 14, 677–691 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Xu J., Laine O., Masciocchi M., Manoranjan J., Smith J., Du S. J., Edwards N., Zhu X., Fenselau C., and Gao L. Y. (2007) A unique Mycobacterium ESX-1 protein co-secretes with CFP-10/ESAT-6 and is necessary for inhibiting phagosome maturation. Mol. Microbiol. 66, 787–800 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05959.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ates L. S., Ummels R., Commandeur S., van der Weerd R., Sparrius M., Weerdenburg E., Alber M., Kalscheuer R., Piersma S. R., Abdallah A. M., Abd El Ghany M., Abdel-Haleem A. M., Pain A., Jiménez C. R., Bitter W., et al. (2015) Essential role of the ESX-5 secretion system in outer membrane permeability of pathogenic mycobacteria. PLoS Genet. 11, e1005190 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Siegrist M. S., Unnikrishnan M., McConnell M. J., Borowsky M., Cheng T.-Y., Siddiqi N., Fortune S. M., Moody D. B., and Rubin E. J. (2009) Mycobacterial Esx-3 is required for mycobactin-mediated iron acquisition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 18792–18797 10.1073/pnas.0900589106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tufariello J. M., Chapman J. R., Kerantzas C. A., Wong K.-W., Vilchèze C., Jones C. M., Cole L. E., Tinaztepe E., Thompson V., Fenyö D., Niederweis M., Ueberheide B., Philips J. A., and Jacobs W. R. Jr. (2016) Separable roles for Mycobacterium tuberculosis ESX-3 effectors in iron acquisition and virulence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, E348–E357 10.1073/pnas.1523321113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tinaztepe E., Wei J. R., Raynowska J., Portal-Celhay C., Thompson V., and Philips J. A. (2016) Role of metal-dependent regulation of ESX-3 secretion in intracellular survival of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 84, 2255–2263 10.1128/IAI.00197-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Garces A., Atmakuri K., Chase M. R., Woodworth J. S., Krastins B., Rothchild A. C., Ramsdell T. L., Lopez M. F., Behar S. M., Sarracino D. A., and Fortune S. M. (2010) EspA acts as a critical mediator of ESX1-dependent virulence in Mycobacterium tuberculosis by affecting bacterial cell wall integrity. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1000957 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Smith J., Manoranjan J., Pan M., Bohsali A., Xu J., Liu J., McDonald K. L., Szyk A., LaRonde-LeBlanc N., and Gao L. Y. (2008) Evidence for pore formation in host cell membranes by ESX-1-secreted ESAT-6 and its role in Mycobacterium marinum escape from the vacuole. Infect. Immun. 76, 5478–5487 10.1128/IAI.00614-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. de Jonge M. I., Pehau-Arnaudet G., Fretz M. M., Romain F., Bottai D., Brodin P., Honoré N., Marchal G., Jiskoot W., England P., Cole S. T., and Brosch R. (2007) ESAT-6 from Mycobacterium tuberculosis dissociates from its putative chaperone CFP-10 under acidic conditions and exhibits membrane-lysing activity. J. Bacteriol. 189, 6028–6034 10.1128/JB.00469-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Simeone R., Bobard A., Lippmann J., Bitter W., Majlessi L., Brosch R., and Enninga J. (2012) Phagosomal rupture by Mycobacterium tuberculosis results in toxicity and host cell death. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1002507 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. van der Wel N., Hava D., Houben D., Fluitsma D., van Zon M., Pierson J., Brenner M., and Peters P. J. (2007) M. tuberculosis and M. leprae translocate from the phagolysosome to the cytosol in myeloid cells. Cell 129, 1287–1298 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Simeone R., Sayes F., Song O., Gröschel M. I., Brodin P., Brosch R., and Majlessi L. (2015) Cytosolic access of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: critical impact of phagosomal acidification control and demonstration of occurrence in vivo. PLoS Pathog. 11, e1004650 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Abdallah A. M., Savage N. D., van Zon M., Wilson L., Vandenbroucke-Grauls C. M., van der Wel N. N., Ottenhoff T. H., and Bitter W. (2008) The ESX-5 secretion system of Mycobacterium marinum modulates the macrophage response. J. Immunol. 181, 7166–7175 10.4049/jimmunol.181.10.7166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Weerdenburg E. M., Abdallah A. M., Mitra S., de Punder K., van der Wel N. N., Bird S., Appelmelk B. J., Bitter W., and van der Sar A. M. (2012) ESX-5-deficient Mycobacterium marinum is hypervirulent in adult zebrafish. Cell. Microbiol. 14, 728–739 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2012.01755.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ates L. S., Houben E. N. G., and Bitter W. (2016) Type VII secretion: a highly versatile secretion system. Microbiol. Spectr. 4, VMBF0011–2015 10.1128/microbiolspec.VMBF-0011-2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gey van Pittius N. C., Sampson S. L., Lee H., Kim Y., van Helden P. D., and Warren R. M. (2006) Evolution and expansion of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis PE and PPE multigene families and their association with the duplication of the ESAT-6 (esx) gene cluster regions. BMC Evol. Biol. 6, 95 10.1186/1471-2148-6-95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Solomonson M., Setiaputra D., Makepeace K. A. T., Lameignere E., Petrotchenko E. V., Conrady D. G., Bergeron J. R., Vuckovic M., DiMaio F., Borchers C. H., Yip C. K., and Strynadka N. C. J. (2015) Structure of EspB from the ESX-1 type VII secretion system and insights into its export mechanism. Structure 23, 571–583 10.1016/j.str.2015.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Korotkova N., Freire D., Phan T. H., Ummels R., Creekmore C. C., Evans T. J., Wilmanns M., Bitter W., Parret A. H., Houben E. N., and Korotkov K. V. (2014) Structure of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis type VII secretion system chaperone EspG5 in complex with PE25-PPE41 dimer. Mol. Microbiol. 94, 367–382 10.1111/mmi.12770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ekiert D. C., and Cox J. S. (2014) Structure of a PE-PPE-EspG complex from Mycobacterium tuberculosis reveals molecular specificity of ESX protein secretion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 14758–14763 10.1073/pnas.1409345111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Korotkova N., Piton J., Wagner J. M., Boy-Röttger S., Japaridze A., Evans T. J., Cole S. T., Pojer F., and Korotkov K. V. (2015) Structure of EspB, a secreted substrate of the ESX-1 secretion system of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Struct. Biol. 191, 236–244 10.1016/j.jsb.2015.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bosserman R. E., Thompson C. R., Nicholson K. R., and Champion P. A. (2018) Esx paralogs are functionally equivalent to ESX-1 proteins but are dispensable for virulence in M. marinum. J. Bacteriol. 200, e00726–17 10.1128/JB.00726-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Renshaw P. S., Lightbody K. L., Veverka V., Muskett F. W., Kelly G., Frenkiel T. A., Gordon S. V., Hewinson R. G., Burke B., Norman J., Williamson R. A., and Carr M. D. (2005) Structure and function of the complex formed by the tuberculosis virulence factors CFP-10 and ESAT-6. EMBO J. 24, 2491–2498 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ilghari D., Lightbody K. L., Veverka V., Waters L. C., Muskett F. W., Renshaw P. S., and Carr M. D. (2011) Solution structure of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis EsxG·EsxH complex: functional implications and comparisons with other M. tuberculosis Esx family complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 29993–30002 10.1074/jbc.M111.248732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chen X., Cheng H. F., Zhou J., Chan C. Y., Lau K. F., Tsui S. K., and Au S. W. (2017) ngor Structural basis of the PE–PPE protein interaction in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 16880–16890 10.1074/jbc.M117.802645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Daleke M. H., Ummels R., Bawono P., Heringa J., Vandenbroucke-Grauls C. M., Luirink J., and Bitter W. (2012) General secretion signal for the mycobacterial type VII secretion pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 109, 11342–11347 10.1073/pnas.1119453109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Champion P. A., Stanley S. A., Champion M. M., Brown E. J., and Cox J. S. (2006) C-terminal signal sequence promotes virulence factor secretion in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science 313, 1632–1636 10.1126/science.1131167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Daleke M. H., van der Woude A. D., Parret A. H., Ummels R., de Groot A. M., Watson D., Piersma S. R., Jiménez C. R., Luirink J., Bitter W., and Houben E. N. (2012) Specific chaperones for the type VII protein secretion. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 31939–31947 10.1074/jbc.M112.397596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Phan T. H., Ummels R., Bitter W., and Houben E. N. (2017) Identification of a substrate domain that determines system specificity in mycobacterial type VII secretion systems. Sci. Rep. 7, 42704 10.1038/srep42704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Champion P. A., Champion M. M., Manzanillo P., and Cox J. S. (2009) ESX-1 secreted virulence factors are recognized by multiple cytosolic AAA ATPases in pathogenic mycobacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 73, 950–962 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06821.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fortune S. M., Jaeger A., Sarracino D. A., Chase M. R., Sassetti C. M., Sherman D. R., Bloom B. R., and Rubin E. J. (2005) Mutually dependent secretion of proteins required for mycobacterial virulence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 10676–10681 10.1073/pnas.0504922102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. MacGurn J. A., Raghavan S., Stanley S. A., and Cox J. S. (2005) A non-RD1 gene cluster is required for Snm secretion in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol. Microbiol. 57, 1653–1663 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04800.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. McLaughlin B., Chon J. S., MacGurn J. A., Carlsson F., Cheng T. L., Cox J. S., and Brown E. J. (2007) A Mycobacterium ESX-1-secreted virulence factor with unique requirements for export. PLoS Pathog. 3, e105 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chen J. M., Zhang M., Rybniker J., Boy-Röttger S., Dhar N., Pojer F., and Cole S. T. (2013) Mycobacterium tuberculosis EspB binds phospholipids and mediates EsxA-independent virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 89, 1154–1166 10.1111/mmi.12336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Abdallah A. M., Verboom T., Hannes F., Safi M., Strong M., Eisenberg D., Musters R. J., Vandenbroucke-Grauls C. M., Appelmelk B. J., Luirink J., and Bitter W. (2006) A specific secretion system mediates PPE41 transport in pathogenic mycobacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 62, 667–679 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05409.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Brodin P., Majlessi L., Marsollier L., de Jonge M. I., Bottai D., Demangel C., Hinds J., Neyrolles O., Butcher P. D., Leclerc C., Cole S. T., and Brosch R. (2006) Dissection of ESAT-6 System 1 of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and impact on immunogenicity and virulence. Infect. Immun. 74, 88–98 10.1128/IAI.74.1.88-98.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Abdallah A. M., Verboom T., Weerdenburg E. M., Gey van Pittius N. C., Mahasha P. W., Jiménez C., Parra M., Cadieux N., Brennan M. J., Appelmelk B. J., and Bitter W. (2009) PPE and PE_PGRS proteins of Mycobacterium marinum are transported via the type VII secretion system ESX-5. Mol. Microbiol. 73, 329–340 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06783.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Houben E. N., Bestebroer J., Ummels R., Wilson L., Piersma S. R., Jiménez C. R., Ottenhoff T. H., Luirink J., and Bitter W. (2012) Composition of the type VII secretion system membrane complex. Mol. Microbiol. 86, 472–484 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08206.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Beckham K. S., Ciccarelli L., Bunduc C. M., Mertens H. D., Ummels R., Lugmayr W., Mayr J., Rettel M., Savitski M. M., Svergun D. I., Bitter W., Wilmanns M., Marlovits T. C., Parret A. H., and Houben E. N. (2017) Structure of the mycobacterial ESX-5 type VII secretion system membrane complex by single-particle analysis. Nat. Microbiol. 2, 17047 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Harboe M., Malin A. S., Dockrell H. S., Wiker H. G., Ulvund G., Holm A., Jørgensen M. C., and Andersen P. (1998) B-cell epitopes and quantification of the ESAT-6 protein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 66, 717–723 10.1128/IAI.66.2.717-723.1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Phan T. H., van Leeuwen L. M., Kuijl C., Ummels R., van Stempvoort G., Rubio-Canalejas A., Piersma S. R., Jiménez C. R., van der Sar A. M., Houben E. N. G., and Bitter W. (2018) Characterization of ESX-1 components EccA1, EspG1 and EspH reveal pivotal role of Esp substrates in the Mycobacterium marinum infection cycle. PLoS Pathog. 14, e1007247 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Stanley S. A., Raghavan S., Hwang W. W., and Cox J. S. (2003) Acute infection and macrophage subversion by Mycobacterium tuberculosis require a specialized secretion system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 13001–13006 10.1073/pnas.2235593100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rosenberg O. S., Dovala D., Li X., Connolly L., Bendebury A., Finer-Moore J., Holton J., Cheng Y., Stroud R. M., and Cox J. S. (2015) Substrates control multimerization and activation of the multi-domain ATPase motor of type VII secretion. Cell 161, 501–512 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wang S., Zhou K., Yang X., Zhang B., Zhao Y., Xiao Y., Yang X., Yang H., Guddat L. W., Li J., and Rao Z. (2020) Structural insights into substrate recognition by the type VII secretion system. Protein Cell 11, 124–137 10.1007/s13238-019-00671-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Poulsen C., Panjikar S., Holton S. J., Wilmanns M., and Song Y.-H. (2014) WXG100 protein superfamily consists of three subfamilies and exhibits an α-helical C-terminal conserved residue pattern. PLoS One 9, e89313 10.1371/journal.pone.0089313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bunduc C. M., Ummels R., Bitter W., and Houben E. N. G. (2020) Species-specific secretion of ESX-5 type VII substrates is determined by the linker 2 of EccC5. Mol. Microbiol. 10.1111/mmi.14496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Unnikrishnan M., Constantinidou C., Palmer T., and Pallen M. J. (2017) The enigmatic Esx proteins: looking beyond Mycobacteria. Trends Microbiol. 25, 192–204 10.1016/j.tim.2016.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Portaliou A. G., Tsolis K. C., Loos M. S., Zorzini V., and Economou A. (2016) Type III secretion: building and operating a remarkable nanomachine. Trends Biochem. Sci. 41, 175–189 10.1016/j.tibs.2015.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Guinn K. M., Hickey M. J., Mathur S. K., Zakel K. L., Grotzke J. E., Lewinsohn D. M., Smith S., and Sherman D. R. (2004) Individual RD1-region genes are required for export of ESAT-6/CFP-10 and for virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol. Microbiol. 51, 359–370 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03844.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Gao L.-Y., Guo S., McLaughlin B., Morisaki H., Engel J. N., and Brown E. J. (2004) A mycobacterial virulence gene cluster extending RD1 is required for cytolysis, bacterial spreading and ESAT-6 secretion. Mol. Microbiol. 53, 1677–1693 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04261.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are contained within this manuscript.